DROSOPHILA melanogaster has played a central role in genetics research since the Morgan lab in the early years of the previous century. Yet, it has played a lesser role in the study of speciation. This is due to the fact that, until recently, there was only one closely related species, D. simulans, and the hybrids between the two species were sterile. Other groups, such as pseudoobscura, provided better opportunities. This changed recently with the discovery in Africa of several closely related species, making a total of nine. This article describes the discovery of these species and some of their salient features not likely to be known to geneticists.

THE NINE SPECIES OF THE MELANOGASTER SUBGROUP

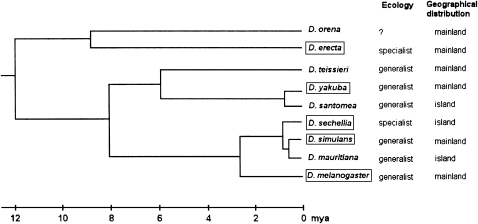

The nine species of the melanogaster subgroup in the Sophophora subgenus of Drosophila is receiving increasing interest from the international community of evolutionary geneticists. This interest is demonstrated, among other ways, by the sequencing of whole genomes. In the drosophilid family, among ∼3500 species, 12 genomes are available, and 5 of them belong to species of the melanogaster subgroup (see legend of Figure 1). All nine included species are easily reared under laboratory conditions, and their phylogeny is well established (Figure 1). Their Afrotropical origin is now accepted. In the future, comparative studies of their morphology, physiology, and behavior will connect genomics and phenomics, as well as ecology. We decided that it was time to explain how these species were discovered and how the hypothesis “out of Africa” has become increasingly accepted. We present below the nine species in the order of description.

Figure 1.—

Consensus phylogeny of the nine species in the melanogaster subgroup. Species for which the entire genome is currently sequenced are boxed. Information on ecology and geographical distribution are also given. Divergence times are still approximate (see Lachaise and Silvain 2004; Tamura et al. 2004).

D. melanogaster Meigen 1830:

This species was described from Austrian flies by Meigen (1830); the name melanogaster refers to the fact that the last two abdominal tergites of the male are completely black. At that time, the description of a new species was very concise, so that the description could apply to several presently known species. The Meigen collection of Diptera, along with two volumes of aquarelles, was bought by the Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris (MNHN) in 1839, thanks to the help of P. J. M. Macquart (see Matile 1974). This collection was examined by one of us (L. Tsacas) and by M. T. Rocha Pité. Under the name of melanogaster, there was one male and two females; the male has been dissected and clearly corresponds to the cosmopolitan D. melanogaster, and it has been designated as the type specimen of the species, although this fact has never been published. Before the publication of Meigen, other studies of Drosophila species with more or less the same external pattern had been published, raising a complex taxonomic and nomenclatural problem. This problem has been extensively discussed by Burla (1951) in his book on Swiss drosophilids. As stated by Burla (p. 79), “der Name melanogaster scheint nich gültiz zu sein” (“the name melanogaster seems invalid”). The valid name (according to the priority rule) could be fasciata. The species is so widespread that it has been described many times. Among newer synonyms, ampelophila Loew (1862) is probably the best known, since it was used by Morgan in his first articles. In this case, and as proposed by Burla (1951), the usage of melanogaster is so widespread that we can ignore the priority rule.

Because of its domestic and cosmopolitan status, the origin of D. melanogaster for long remained a mystery. But now, an Afrotropical origin, which was first suggested by Tsacas and Lachaise (1974), is widely accepted. The two strongest arguments are, first, that (ancestral) Afrotropical populations are more polymorphic than elsewhere in the world and, second, that most related species are endemic in the Afrotropical region.

The history of world colonization by D. melanogaster is fairly well known and is due to human transportation (see David and Capy 1988). It has long been assumed that, because of the uniformity of its human-linked ecological niche, all populations of D. melanogaster would be genetically similar. But extensive investigations of natural populations have led to the opposite conclusion (David and Capy 1988). Among all Drosophila species, D. melanogaster is probably the most differentiated into geographic subpopulations or races, according to habitats (alcohol tolerance) or climate (latitudinal clines). Each gene, or group of genes, raises specific adaptive problems leaving, even now, a large number of unanswered questions. In particular, the paradox remains that the species can be spread by human migrations and still show adaptations to particular environments not related to human activity.

D. simulans Sturtevant 1919:

D. simulans is the other cosmopolitan species in the subgroup. It was discovered by Sturtevant (1919) on the basis of “interspecific” crosses producing sterile or lethal hybrids, and more information was provided by Provine (1991). At the time of the original description, the morphology was considered to be so close to that of D. melanogaster (the male genitalia of D. simulans were not considered at that time) that many people doubted that it was a distinct species. Now the progressive accumulation of biological information has revealed that in most aspects of its morphology, life history, and genetic architecture, D. simulans is very different from its “sibling.” Even a short review would be beyond the scope of this article, but fortunately a large part of our extant knowledge has recently been summarized in a symposium (Capy and Gibert 2004). There are, however, some salient features in D. simulans worth recalling here.

First, in spite of its cosmopolitan status and its capacity to proliferate under tropical and temperate climates, D. simulans is not found in all places of the world with suitable climates, contrary to D. melanogaster. It is absent from most of West Africa and is very rare in the Côte d'Ivoire. It is absent in most parts of East Asia, presumably starting from the eastern Caucasus. One of us (J. R. David) was able to investigate natural populations in the southern part of the Caucasus. D. simulans was very abundant in Sotchi, Russia (our unpublished results), but completely absent from Daghestan (Imasheva et al. 1994), despite a continuity of apparently very favorable Mediterranean habitats. Finally, D. simulans is absent from some French Carribbean islands (Martinique and Guadeloupe), while it is very common in the nearby island of St. Martin. The reason for these geographic discontinuities remains an ecological mystery. We may expect that, in the future, D. simulans will invade these “empty places.” It may also be suggested that this species, which is less related to human activities, is also less often transported by modern humans.

The second problem with D. simulans is its ecology. It is true that, during the fruiting season, adults can be collected in great abundance in orchards and that larvae are found in rotting fruits. But, in various countries, D. simulans is very abundant in spring, in places where there are absolutely no sweet fruits. This is a classical observation in North Africa, southern Spain, and also in Uruguay (J. R. David, unpublished results) in habitats with a mild temperature and high humidity and with a diversity of grass species growing in shadowed places. We certainly do not know the breadth of the ecological niche of this species. Perhaps its success in Mediterranean and subtropical places, as compared to D. melanogaster, is due to its capacity to use a diversity of rotting, nonsweet substrates in most seasons of the year, preventing strong seasonal demographic bottlenecks.

A third remarkable characteristic of D. simulans is that its natural populations harbor one of three different mitochondrial (mt) haplotypes (Aubert and Solignac 1990). Type I is typical of the Seychelles, mt II is the worldwide type, and mt III seems endemic to Madagascar. These observations provide a strong argument for assuming that the three types have evolved in isolation during a long period (∼2 MY). Surprisingly, the morphologies of D. melanogaster and D. simulans have remained very similar. In the Seychelles archipelago, the drosophilids were collected at the beginning of the 20th century and several new species were described by Lamb (1914) at a time when the taxonomic knowledge was very limited. In this work, Lamb mentioned the occurrence of D. melanogaster, a surprising observation since, even now, this species is very rare in the Seychelles and restricted to human habitats (David and Capy 1982). Fortunately, Lamb's specimens have been kept in the Cambridge (UK) museum, and their examination (by J. R. David) revealed that they were in fact D. simulans. That species could have been described in the Seychelles 5 years before Sturtevant's discovery in 1919 if taxonomists had paid attention to male genitalia.

D. yakuba Burla 1954:

In his magisterial work on the drosophilids of the Côte d'Ivoire, Burla (1954) described a new African species, D. yakuba, and noted that it was closely related to D. melanogaster. This species is the most abundant among the African endemics and is highly domestic and widespread in sub-Saharan tropical Africa. It is also abundant in Madagascar but not in other Indian Ocean islands. The same species was previously described in 1950 by Nolte and Stoch (1950) as D. opisthomelaina. The description, however, appeared in Drosophila Information Service, which, at that time, was not considered to be a scientific journal. Therefore, the name opisthomelaina lacks priority (see McEvey 1990 for more details and discussion).

D. yakuba has not been extensively studied, except for its numerous chromosomal rearrangements (Lemeunier et al. 1986). Because of its broad distribution, D. yakuba is likely to exhibit some geographic differentiation.

D. teissieri Tsacas 1971:

This species was first collected by H. Paterson on Mount Selinda (Zimbabwe) in 1970 and described by Tsacas (1971).

D. teissieri is related to D. yakuba and they share almost identical mitochondria, in spite of the fact that they do not produce hybrids in the laboratory. It is a forest-dwelling species far less abundant than yakuba and with a more restricted geographical range on the African mainland (Lachaise et al. 1988). D. teissieri is morphologically very different from D. yakuba and remarkable for the presence of very strong spines on the anal plates (cerci) above the male genitalia. Indeed, the position of these spines is genetically variable and helps to discriminate geographic populations with a northwest–southeast cline (Lachaise et al. 1981).

D. erecta Tsacas and Lachaise 1974:

D. erecta was also discovered in the Côte d'Ivoire by D. Lachaise (Lachaise and Tsacas 1974). It is remarkable for its ecological specialization on Pandanus fruits. During the fruiting season, which lasts several months, D. erecta becomes very abundant along the rivers where Pandanus trees grow. During the rest of the year, it is extremely rare and its frequency among collected drosophilids drops to <1% (J. R. David, unpublished observations in the Congo). D. erecta should be an excellent model for investigating the genetic consequences of very strong and repetitive seasonal bottlenecks. D. erecta is also remarkable for a scarcity of chromosome inversions (Rio et al. 1983) and for a single locus polymorphism of female abdomen pigmentation, with either a completely yellow (recessive) color or a dark (dominant) pigmentation. In the species description, Lachaise and Tsacas (1974) suggested for the first time that, since three species (yakuba, teissieri, and erecta) were endemic to the Afrotropical region, the two cosmopolitans could also be native to that region.

D. mauritiana Tsacas and David 1974:

This species is endemic in the Mauritius Island in the Indian Ocean, and it does not coexist with its sibling D. simulans. Its discovery was somewhat accidental, and a by-product of a search for cheap intercontinental air fares. In early 1970s, planes were very expensive and there were very few chartered flights. The objective of J. R. David was to explore the French Réunion Island, but plane prices were prohibitive. It turned out that it was possible to go to Mauritius for a much lower price, and this provided an opportunity to collect some drosophilids on the island. A few days later, a laboratory equipped with a convenient microscope on Réunion permitted the examination of the Mauritius material. Tsacas and David (1974) found that a species, obviously belonging to the melanogaster subgroup, was probably new because of the special shape of the male genitalia: this was D. mauritiana.

D. mauritiana is endemic to Mauritius and Rodrigues islands. It is widespread in both natural and domestic habitats (David et al. 1989) and its large population size is related to a high level of genetic polymorphism. Natural populations harbor two different mt types (Solignac and Monnerot 1986). One is specific to D. mauritiana, the other one is D. simulans type I, presumably the consequence of an introgression. Crosses between D. mauritiana and D. simulans produce fertile F1 females but sterile males. These species are now a paradigm for the analysis of interspecific isolation.

D. orena Tsacas and David 1978:

In 1975, an expedition sponsored by the French CNRS and headed by L. Tsacas explored the drosophilids of the Cameroon Mountains. Because of bad weather conditions, the expedition was obliged to stay on a mountain near Bafut N'Gemba at an altitude of 2100 m. The habitat was nothing special; it was a secondary forest with large stands of Eucalyptus. Drosophilids, collected with banana traps, were not abundant, but several species in the subgroup were present, including D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. yakuba, and D. teissieri. One day, L. Tsacas, while examining male specimens, announced the great news: there is a new species in the subgroup! We did not have any idea of what the female would look like, and J. R. David started to isolate all the potential females in small culture vials. These vials were eventually brought to France and, among ∼25 fertile isofemale lines, only 1 belonged to the new species, which was eventually called orena (in Greek, orena means “highlander”; Tsacas and David 1978). During the expedition and later, other Cameroon mountains were prospected, with no success. Indeed, the type locality was prospected again in 2005 and 2006 by D. Lachaise and M. Veuille, without success. D. orena is certainly very rare and might be a specialized species. Further investigations revealed that D. orena is closely related to D. erecta. An interesting feature is that the single isofemale line harbored several chromosome rearrangements (Lemeunier et al. 1986), while the karyotype of D. erecta, which has been extensively investigated in this respect, is almost monomorphic.

D. sechellia Tsacas and Bächli 1981:

Thanks to the sponsorship of the CNRS, the drosophilids of the Seychelles could be investigated again (by L. Tsacas and J. R. David in 1977)—that is, 70 years after Lamb's (1914) publication. We obtained evidence that several invasive drosophilid species, such as D. malerkotliana, Zaprionus indianus, and Z. tuberculatus, had appeared and were very abundant. But D. sechellia, which is highly specialized on a single resource, the fruit of Morinda citrifolia, was not discovered. This failure is due to the fact that our adult collections were done either with banana traps or by sweeping with a net. At that time, we had no idea that a fruit-breeding species could be so specialized as not to come to fermenting bananas.

A few years later (1980), a group of Oxford students organized another expedition to the Seychelles to collect drosophilids. With the help of M. Ashburner in Cambridge, they contacted G. Bächli in Zurich, who agreed to receive and study the collected material. When he received the alcohol-preserved flies, G. Bächli identified a species of the melanogaster subgroup, which was probably new. The species was sent by him to L. Tsacas for confirmation, and it was eventually described as D. sechellia (Tsacas and Bächli 1981). Live material was later collected by J. R. David on Morinda in the Cousin islet, near Praslin island, and it turned out that the species could be reared on ordinary Drosophila medium, although with great difficulty because of the low fertility of the females.

Since that date, D. sechellia, which is very close to D. simulans and D. mauritiana (Lachaise and Silvain 2004), has been the subject of many investigations. The most salient feature is its specialization on a toxic resource, which implies a tolerance to the toxins (medium-length aliphatic acids) and also a diversity of physiological and behavioral adaptations (R'kha et al. 1991). So far, the relevant genes have not been identified, despite many attempts to do so. These specific adaptations were presumably the main argument for sequencing the whole genome of D. sechellia.

D. santomea Lachaise and Harry 2000:

Between 1980 and 2000, D. Lachaise had the opportunity to explore various countries in the Afrotropical region, with the hope of finding another new species in the subgroup. This expectation was finally fulfilled in 1998 by the discovery, on São Tomé island, of a new species that was later described as D. santomea (Lachaise et al. 2000). D. santomea is closely related to D. yakuba with which it produces sterile F1 males and fertile F1 females. On São Tomé, D. yakuba is found at a low elevation, presumably as a consequence of a recent introduction, while D. santomea is montane. The contact between the two species permits some crosses, with the occurrence of a hybrid zone (Llopart et al. 2005). D. santomea is mostly notable by the pale yellow color of the abdomen in both sexes, while the eight other species all have males with dark abdomens. The genetic basis of this character and of some other traits has been investigated in several publications (e.g., Llopart et al. 2002).

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

A major question is: Are there one or more species in the melanogaster subgroup still waiting to be described in Africa? Obviously, there is no definitive answer, so we can only conjecture. Even now, many Afrotropical places remain to be explored. Ecological specialization has occurred at least twice in the subgroup, and any unknown specialist species would certainly be difficult to find, especially if the adults are not attracted to the usual fermenting banana traps. Therefore, the existence of still-undiscovered species remains a likely hypothesis.

A second comment is that five of nine genomes are now available, which provides great opportunities for genomic studies with a comparative approach. Despite extensive genomic information, our knowledge of the phenotypic characteristics of the nine species is, surprisingly, far from satisfying. In fact, only the two cosmopolitan species have been continuously investigated, presumably because they are abundant and accessible all over the world. For the other species, much remains to be studied on life-history traits, morphometry, phenotypic plasticity, thermal tolerance, and, of course, ecology. The great and practically unique advantage of the drosophilid family for evolutionary studies is the capacity of >500 species to be cultured in the laboratory under controlled conditions permitting correlation of genomics and phenomics. In the melanogaster subgroup, a strong research effort on phenotypes is still needed.

Another perspective concerns the problem of biodiversity and the way to identify species. Aware that a complete inventory is a very difficult task, especially for species of small size, many taxonomists propose a molecular way for identifying species, a method known as DNA barcoding (Desalle et al. 2005). This is based on the sequencing of a mitochondrial gene (CO-I) in any collected individual. Two individuals with the same sequence will be assigned to the same species, while different species will be suspected if the sequences are different. The melanogaster subgroup is an illustration of the limitations of this method and the dangers of generalizations. Under the barcode hypothesis, three bona fide species (D. yakuba, D. teissieri, and D. santomea) would be considered as the same species, since they have almost identical mitochondria. Reciprocally, the three mitochondrial types in D. simulans would lead to the description of three species, and D. sechellia would probably be a mere subspecies of D. simulans type I. The barcode method is certainly very useful as a first taxonomic approach for species that cannot be reared or crossed, but morphological studies and hybridization experiments, when available, will still be required. An integrative approach, using different criteria, remains the ultimate way to identify cryptic species. This was recently illustrated by the discovery of two close African relatives of the cosmopolitan drosophilid Zaprionus indianus (Yassin et al. 2007).

Finally, it is worth mentioning that, among the nine known species in the subgroup, the type specimens of seven of them are deposited in the MNHN in Paris. This is indicative of the major contribution of the French investigators to the discoveries of these species.

As a serious research effort—molecular, genomic, geographical, and ecological—on the melanogaster group goes forward, we hope that this account of the discovery of the nine known species will be of interest to geneticists in general and to those interested in speciation, as well as those carrying out research on these species.

References

- Aubert, J., and M. Solignac, 1990. Experimental evidence for mitochondrial DNA introgression between Drosophila species. Evolution 44: 1272–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burla, H., 1951. Systematik, verbreitung und oekologie der Drosophila-arten der schweiz. Rev. Suisse Zool. 58: 23–175. [Google Scholar]

- Burla, H., 1954. Zur kenntnis der Drosophiliden der elfenbeinkuste (Franzosisch West-Afrika). Rev. Suisse Zool. 61: 1–218. [Google Scholar]

- Capy, P., and P. Gibert, 2004. Drosophila melanogaster, Drosophila simulans: so similar yet so different. Genetica 120: 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David, J. R., and P. Capy, 1982. Genetics and origin of a Drosophila melanogaster population recently introduced to the Seychelles. Genet. Res. 40: 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- David, J. R., and P. Capy, 1988. Genetic variation of Drosophila melanogaster natural populations. Trends Genet. 4: 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David, J. R., S. F. McEvey, M. Solignac and L. Tsacas, 1989. Drosophila communities on Mauritius and the ecological niche of D. mauritiana (Diptera, Drosophilidae). Rev. Zool. Afr. 103: 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalle, R., M. G. Egan and M. Siddall, 2005. The unholy trinity: taxonomy, species delimitation and DNA barcoding. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 360: 1905–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imasheva, A. G., O. E. Lazebny, M.-L. Cariou, J. R. David and L. Tsacas, 1994. Drosophilids from Daghestan (Russia) with description of a new species (Diptera). Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 30: 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise, D., and J.-F. Silvain, 2004. How two Afrotropical endemics made two cosmopolitan human commensals: the Drosophila melanogaster-D. simulans paleogeographic riddle. Genetica 120: 17–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise, D., and L. Tsacas, 1974. Les Drosophilidae des savanes préforestrières de la région tropicale de Lamto (Côte-d'Ivoire). II. Le peuplement des fruits de Pandanus candelabrum (Pandanacées). Ann. Univ. Abidjan Ser. G 7: 153–193. [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise, D., F. Lemeunier and M. Veuille, 1981. Clinal variations in male genitalia in Drosophila teissieri Tsacas. Am. Nat. 117: 600–608. [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise, D., M. L. Cariou, J. R. David, F. Lemeunier, L. Tsacas et al., 1988. Historical biogeography of the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. Evol. Ecol. 22: 159–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise, D., M. Harry, M. Solignac, F. Lemeunier, V. Benassi et al., 2000. Evolutionary novelties in islands: Drosophila santomea, a new melanogaster sister species from Sao Tomé. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 267: 1482–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, C. G., 1914. The Percy Sladen Trust expedition to the Indian Ocean in 1905. XV. Diptera: Heteroneuridae, Ortalidae, Trypetidae, Sepsidae, Micropezidae, Drosophilidae, Geomyzidae, Milichidae. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. Zool. 16: 307–372. [Google Scholar]

- Lemeunier, F., J. R. David, L. Tsacas and M. Ashburner, 1986. The melanogaster species group, p. 5 in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, Vol. 3, edited by M. Ashburner, H. L. Carson and J. N. Thompson. Academic Press, New York.

- Llopart, A., S. Elwyn, D. Lachaise and J. A. Coyne, 2002. Genetics of a difference in pigmentation between Drosophila yakuba and Drosophila santomea. Evolution 56: 2262–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llopart, A., D. Lachaise and J. A. Coyne, 2005. Multilocus analysis of introgression between two sympatric sister species of Drosophila: Drosophila yakuba and D. santomea. Genetics 171: 197–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loew, H., 1862. Diptera Americae septentrionalis indigena. Centuria secunda. Deutsche entomologische Zeitschrift 6: 185–232. [Google Scholar]

- Matile, L., 1974. Découverte de dessins inédits du diptériste J. W. Meigen. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 79: 104. [Google Scholar]

- McEvey, S. F., 1990. New synonym of D. yakuba Burla 1954 (Diptera Drosophilidae). Syst. Entomol. 15: 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Meigen, J. W., 1830. Systematische Beschreibung der Bekannten Europaischen Zweiflugeligen Insekten, Vol. 6. Theil Schulze, Vienna.

- Nolte, V. J., and Z. A. Stoch, 1950. A new South African species, D. opisthomelaina. Dros. Inf. Serv. 24: 90. [Google Scholar]

- Provine, W. B., 1991. Alfred Henry Sturtevant and crosses between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. Genetics 129: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R'kha, S., P. Capy and J. R. David, 1991. Host-plant specialization in the Drosophila melanogaster species complex: a physiological, behavioral, and genetical analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 1835–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio, B., G. Coutunier, F. Lemeunier and D. Lachaise, 1983. Evolution d'une spécialisation saisonnière chez Drosophila erecta (Dipt. Drosophilidae). Annals Soc. Ent. Fr. 19: 235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Solignac, M., and M. Monnerot, 1986. Race formation, speciation, and introgression within Drosophila simulans, D. mauritiana, and D. sechellia inferred from mitochondrial DNA analysis. Evolution 40: 531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., 1919. A new species closely resembling Drosophila melanogaster. Psyche (J. Entomol.) 26: 153–155. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K., S. Subramania and S. Kumar, 2004. Temporal patterns of fruitfly (Drosophila) evolution revealed by mutation clocks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21: 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsacas, L., 1971. Drosophila teissieri, nouvelle espèce africaine du groupe melanogaster et note sur deux autres espèces nouvelles pour l'Afrique (Dipt: Drosophilidae). Bull. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 76: 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tsacas, L., and G. Bächli, 1981. Drosophila sechellia, n. sp., huitième espèce du sous-groupe melanogaster des Iles Seychelles (Diptera, Drosophilidae). Rev. Fr. Entomol. 3: 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Tsacas, L., and J. David, 1974. Drosophila mauritiana n. sp. du groupe melanogaster de l'île Maurice. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 79: 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tsacas, L., and J. David, 1978. Une septième espèce appartenant au sous-groupe Drosophila melanogaster Meigen: Drosophila orena spec. nov. du Cameroun (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Beitr. Entomol. 28: 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tsacas, L., and D. Lachaise, 1974. Quatre nouvelles espèces de la Côte d'Ivoire du genre Drosophila, groupe melanogaster, et discussion de l'origine du sous-groupe melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Ann. Univ. Abidjan Ser. G 7: 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Yassin, A., P. Capy, L. Madi-Ravazzi, D. Ogereau and J. R. David, 2007. DNA barcode discovers two cryptic species and two geographic radiations in the invasive drosophilid Zaprionus indianus. Mol. Ecol. Notes (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]