Abstract

The Spt-Ada-Gcn5-acetyltransferase (SAGA) complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a multifunctional coactivator complex that has been shown to regulate transcription by distinct mechanisms. Previous results have shown that the Spt3 and Spt8 components of SAGA regulate initiation of transcription of particular genes by controlling the level of TATA-binding protein (TBP/Spt15) associated with the TATA box. While biochemical evidence exists for direct Spt8–TBP interactions, similar evidence for Spt3–TBP interactions has been lacking. To learn more about Spt3–TBP interactions in vivo, we have isolated a new class of spt3 mutations that cause a dominant-negative phenotype when overexpressed. These mutations all cluster within a conserved region of Spt3. The isolation of extragenic suppressors of one of these spt3 mutations has identified two new spt15 mutations that show allele-specific interactions with spt3 mutations with respect to transcription and the recruitment of TBP to particular promoters. In addition, these new spt15 mutations partially bypass an spt8 null mutation. Finally, we have examined the level of SAGA–TBP physical interaction in these mutants. While most spt3, spt8, and spt15 mutations do not alter SAGA–TBP interactions, one spt3 mutation, spt3-401, causes a greatly increased level of SAGA–TBP physical association. These results, taken together, suggest that a direct Spt3–TBP interaction is required for normal TBP levels at Spt3-dependent promoters in vivo.

EUKARYOTIC transcription initiation requires many different classes of protein factors for transcription to occur in a specific and regulated fashion. One large and critical set of factors is coactivators, large multi-protein complexes that are recruited to regulatory regions by site-specific DNA binding factors. Different coactivators have been shown to regulate transcription by a variety of mechanisms, including recruitment of general transcription factors, covalent modification of histones, and remodeling or movement of nucleosomes (Naar et al. 2001; Martinez 2002).

One coactivator complex that has been extensively studied is SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5-acetyltransferase). Originally identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, SAGA is highly conserved in terms of function, composition, and structure (Timmers and Tora 2005; Daniel and Grant 2007). Several lines of evidence have established that SAGA is multifunctional, capable of activating transcription by several distinct mechanisms (Martinez 2002; Timmers and Tora 2005) as well as playing a role in mRNA export (Rodriguez-Navarro et al. 2004; Cabal et al. 2006). Two of the transcriptional activation mechanisms by which SAGA functions are dependent upon characterized histone modifying enzymes within SAGA: Gcn5, a histone acetyltransferase (Brownell et al. 1996; Grant et al. 1997), and Ubp8, a histone deubiquitylase (Henry et al. 2003; Daniel et al. 2004). Gcn5 has been shown to play broad roles in transcriptional regulation (Lee et al. 2000), while Ubp8 has been shown to play roles in transcription, histone methylation levels, and mRNA export (Henry et al. 2003; Kohler et al. 2006; Shukla et al. 2006). Recent evidence suggests that both Gcn5 and Ubp8 function along transcribed sequences as well as in regulatory regions (Govind et al. 2007; Wyce et al. 2007).

A third set of components by which SAGA controls transcription are Spt3 and Spt8. In their most widely studied role, these two factors have been shown to activate transcription by the recruitment of the general transcription factor TATA-binding protein (TBP) to particular promoters in vivo (Dudley et al. 1999b; Bhaumik and Green 2001, 2002; Larschan and Winston 2001). In other cases, Spt3 and Spt8 have been shown to play the opposite role, by inhibiting TBP–TATA interactions (Belotserkovskaya et al. 2000; Yu et al. 2003). The factors that determine positive vs. negative regulation by Spt3 and Spt8 are not currently understood, although the factors Swi/Snf or yFACT may play a role (Biswas et al. 2005; Mitra et al. 2006). In addition to controlling the level of TBP–TATA interaction, Spt3 and Spt8 have been implicated in recruiting Mot1 to activate transcription by a mechanism independent of TBP recruitment (Topalidou et al. 2004; Van Oevelen et al. 2005). A recent study also suggests a role for Spt3 outside of SAGA (James et al. 2007).

Different studies have provided mixed views of the nature of the Spt3–TBP and Spt8–TBP interactions. Genetic studies involving allele-specific interactions have implicated Spt3 as having a direct interaction with TBP (Eisenmann et al. 1992; Larschan and Winston 2001). In addition, Spt3 is homologous to two human TAFs, TAF11 and TAF13, which have been shown to interact directly with TBP (Mengus et al. 1995; Birck et al. 1998; Lavigne et al. 1999). Biochemical experiments have not yet been able to demonstrate direct Spt3–TBP interactions. In contrast, three different studies have shown that Spt8 can interact directly with TBP in vitro (Belotserkovskaya et al. 2000; Warfield et al. 2004; Sermwittayawong and Tan 2006). One of these studies also showed that, in vitro, Spt8 and TATA box DNA compete for binding to TBP, suggesting a two-step model in which SAGA, via Spt8, binds TBP to facilitate its subsequent transfer to a TATA box (Sermwittayawong and Tan 2006). While these studies suggest that Spt8 acts more directly than Spt3 in TBP recruitment, this possibility does not fit well with earlier results that a particular spt3 mutation can suppress an spt8Δ mutation (Eisenmann et al. 1994) and that one form of SAGA lacks Spt8 (Pray-Grant et al. 2002; Sterner et al. 2002; Wu and Winston 2002).

To learn more about the role of Spt3 and its possible functional interactions with TBP, we have identified dominant-negative spt3 mutations and found that these mutations cluster within a conserved region of Spt3. A search for extragenic suppressors of one of these spt3 mutations identified mutations in both SPT3 and SPT15 (TBP). Furthermore, analysis of the new spt15 suppressor mutations demonstrated that they are also able to partially bypass the requirement for Spt8. Finally, purification of SAGA from several mutants revealed that one spt3 mutation causes an aberrantly high level of SAGA–TBP association. Taken together, these results support the idea that Spt3 and TBP specifically recognize each other in a way that is required for SAGA-mediated regulation at particular promoters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, genetic methods, and plasmids:

All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are descended from a GAL2+ derivative of S288C (Winston et al. 1995). Standard methods for mating, sporulation, transformation, gene replacement, and tetrad analysis were used (Rose et al. 1990). Yeast growth media, including rich medium (YPD) and synthetic complete medium lacking particular nutrients (for example, SC-His) have been previously described (Rose et al. 1990). Plasmid pDR11 is a high-copy-number (2μ) URA3 plasmid derived from pDAD2 (generously provided by David Pellman). In pDR11, the SPT3 coding region is under control of the GAL10 promoter. pDR77 contains the spt3-193 mutant cloned into pRS306. We have used lower-case nomenclature to denote the spt3 mutations as they are recessive when integrated in the genome.

Isolation of spt3 dominant-negative mutations:

To screen for spt3 mutants, SPT3 was mutagenized using standard PCR conditions previously shown to be successful (Hirschhorn et al. 1995). In addition, plasmid pDR11 was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and the vector portion was purified. The mutagenized SPT3 PCR fragment and the purified pDR11 fragment were then mixed and used to cotransform S. cerevisiae strain FY374 (Table 1). By this procedure, the PCR fragment is able to recombine with the vector to reconstitute a complete plasmid (Muhlrad et al. 1992). Ura+ transformants were then screened by replica plating onto plates lacking histidine and containing galactose as the carbon source. This tested for suppression of the his4-917 insertion mutation, previously shown to be suppressed by spt3 mutations (Winston et al. 1984a). Approximately 70,000 transformants were screened from seven independent pools of PCR-mutagenized SPT3.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| FY294 | MATaspt3-202 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63 |

| FY295 | MATα spt3-202 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY374 | MATα his4-917 lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2 trp1Δ63 |

| FY631 | MATahis4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 |

| FY1762 | MATα spt15-239 his4-917δ arg4-12 trp1Δ63 ura3-52 |

| FY1976 | MATα his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2006 | MATα spt3-193 ura3-52 lys2-173R2 his4-917δ leu2Δ1 |

| FY2007 | MATaspt3-193 ura3-52 lys2-173R2 his4-917δ trp1Δ63 |

| FY2031 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2037 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 spt8Δ302∷LEU2 ura3-52 |

| FY2040 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trp1Δ63 spt3-203∷TRP1 ura3Δ0 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2529 | MATα his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 spt3-401 |

| FY2542 | MATaspt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2543 | MATaspt15-239 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 |

| L810 | MATα spt15-21 spt3Δ203∷TRP1 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ1 |

| FY2678 | MATα spt3-193 401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2679 | MATα spt3-193 spt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2680 | MATα spt3-193 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 spt15-239 |

| FY2681 | MATaspt3-193 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 spt15-239 |

| FY2682 | MATα spt3-193 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2683 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 spt15-21 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2684 | MATα spt8Δ302∷LEU2 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2685 | MATahis4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 spt3-193 spt15-21 |

| FY2686 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trp1Δ63 spt15-21 spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2687 | MATα HA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trp1Δ63 spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2688 | MATa HA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trp1Δ63 spt3-193 spt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2689 | MATα HA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trp1Δ63 spt3-193 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2690 | MATα HA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trpΔ63 spt3-193 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2691 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 spt8Δ302∷LEU2 spt3Δ0∷clonNat ura3-52 |

| FY2692 | MATaHA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trp1Δ63 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 spt15-180 |

| FY2693 | MATaspt3-401 spt15-21 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2694 | MATα spt3-401 spt15-239 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2695 | MATaspt3-401 spt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2696 | MATα spt3-193,401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2697 | MATα spt3-193 spt15-239 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2698 | MATα spt3-193 spt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2699 | MATaspt3-202 spt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2700 | MATα spt3-202 spt15-239 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2701 | MATα gcn5Δ0∷kanMX his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2702 | MATα gcn5Δ0∷kanMX spt3-202 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 |

| FY2703 | MATα gcn5Δ0∷kanMX spt3-193 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2704 | MATα gcn5Δ0∷kanMX spt3-193 spt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2705 | MATagcn5Δ0∷kanMX spt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2706 | MATagcn5Δ0∷kanMX spt15-239 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2707 | MATα gcn5Δ0∷kanMX spt3-193 spt15-239 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2708 | MATα HA-SPT7-TAP∷TRP1 trpΔ63 spt3-196 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 |

| FY2709 | MATα spt8Δ302∷LEU2 spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2710 | MATα spt8Δ302∷LEU2 spt15-180 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3-52 |

| FY2711 | MATα spt8Δ302∷LEU2 spt15-239 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3-52 |

Isolation and genetic analysis of suppressors of spt3-193:

Fifty single colonies each for S. cerevisiae strains FY2006 and FY2007 (Table 1) were inoculated into 1 ml YPD cultures and grown to saturation. Each of the 100 cultures was washed twice with sterile water, resuspended in sterile water, and plated (0.1 ml) on synthetic complete medium lacking lysine and containing galactose as the carbon source (SC Gal-Lys plates). The plates were irradiated with 50 μJ of ultraviolet (UV) light using a Stratalinker (Stratagene) and the plates were incubated at 30° for 5 days, after which there were ∼1000 colonies per plate. Two colonies from each plate were purified and saved for further study. A pilot test showed that UV irradiation stimulated the frequency of colony formation under these conditions and therefore each mutant was considered to be independent. Following purification, the 200 candidates were screened for strong suppression by testing for growth on SC-Gal, SC-Lys, and SC-His to test spt3-193 phenotypes. This led to the identification of 73 candidates. Of these, 44 were shown to be recessive and the 10 with the strongest phenotypes were chosen for additional analysis. In addition, one suppressor of spt3-193 was isolated by a modification of the above method, beginning with strain FY294 (Table 1) containing plasmid H45a (pDR11 with the spt3-193 mutation). In this case, Lys+ suppressors were selected, screened for those with a His− phenotype, and a single suppressor was identified.

RNA isolation and Northern analysis:

To prepare RNA, strains were grown to 1–2 × 107 cells/ml in YPD. RNA isolation and Northern analysis were performed as previously described (Ausubel et al. 1991; Swanson et al. 1991). The Ty1 probe used for Northern analysis has been previously described (Winston et al. 1987). Probes for BDF2, HO, and ACT1 were synthesized by PCR amplification from genomic DNA and labeled with [α-32P]dATP by random priming (Ausubel et al. 1991). The specific regions amplified and the primers used are as follows: BDF2, +716 to +1215 (5′ TGCCACCAAGAGTTTTACCC 3′ and 5′ GCCTTCTGGATTGAATTGGA 3′); HO, +445 to +651 (5′ TGGAGCGCTCTAAAGGAGAA 3′ and 5′ ACCAAGCATCCAAGCCATAC 3′); and ACT1, −376 to +1015 (5′ TACCCGCCACGCGTTTTTTTCTTT 3′ and 5′ ATTGAAGAAGATTGAGCAGCGGTTTG 3′).

TAP purifications:

TAP purifications (Rigaut et al. 1999) were performed as previously described (Wu and Winston 2002) except that the extract with 800 μl of 1:1 immunoglobulin G (IgG)-Sepharose (Sigma) was incubated at 4° overnight. Silver staining of the SDS–PAGE gels was done using a kit from Invitrogen.

Protein extracts and Western analysis:

Whole-cell protein extracts were prepared as previously described (Wu and Winston 2002) and protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of whole-cell extracts or TAP-purified complexes were separated on SDS–PAGE gels. Transfer was performed as previously described (Swanson and Winston 1992). The following antibodies were used at the following dilutions: TBP (1:2500) and Spt3 (1:2000). The TBP antibodies were kindly provided by Steve Buratowski and Greg Prelich, and the Spt3 antibodies were kindly provided by Martine Collart. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Labs) were used at a 1:10,000 dilution and were detected by chemiluminescence (Perkin Elmer). The 12CA5 anti-HA1 antibody (used at 1:5000) was a generous gift from Brad Cairns.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of TBP binding:

Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were done as previously described (Shirra et al. 2005). The primers for the BDF2 TATA region were 5′ GACTCAAATAAATGCGCGATG 3′ and 5′ TTAGTACGAGACATAGCCGCC 3′, and the primers used for an untranscribed region have been previously described (Komarnitsky et al. 2000). TBP antibodies provided by Greg Prelich were used for the immunoprecipitations, using 2 μl in each experiment. Dilutions of input DNA (1/50, 1/100, and 1/200) and immunoprecipitated DNA (1/1, 1/2, and 1/4 for TBP) were analyzed by quantitative PCR and the products were separated on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. In each experiment, the percent immunoprecipitation was calculated and normalized to an untranscribed region on chromosome V.

RESULTS

Isolation and analysis of spt3 dominant-negative mutants:

Previous studies have demonstrated that Spt3 is a component of the SAGA coactivator complex, although it is not required for the structural integrity of the complex (Grant et al. 1997; Roberts and Winston 1997; Sterner et al. 1999; Wu and Winston 2002; Wu et al. 2004). To understand more about the interactions of Spt3 with other proteins, both within SAGA and outside of SAGA, and to identify new classes of spt3 mutants, we sought to isolate dominant-negative spt3 alleles. Dominant-negative mutations have been hypothesized to disrupt wild-type function by many possible avenues (Herskowitz 1987).

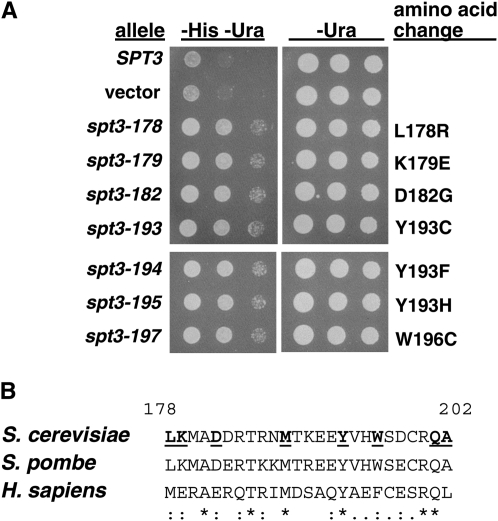

To isolate such mutants, we mutagenized the SPT3 gene and screened candidates for an Spt− phenotype upon overexpression in an SPT3+ host (described in materials and methods). The Spt− phenotype tested was suppression of the His− phenotype conferred by his4-917, previously described for spt3 mutants (Winston et al. 1984a). This insertion mutation was chosen as it is more permissive for suppression than other Ty or solo δ insertion mutations. From an initial screen of 70,000 transformants, 270 were scored as His+/Spt−. Of these, 98 candidates were recovered into Escherichia coli, and 79 of them again conferred an Spt− phenotype after retransformation of an SPT3+ host strain, FY374 (Figure 1A, Table 2, and data not shown). Twenty-four of these plasmids were then sequenced and 17 are predicted to cause single amino acid changes at nine different positions in Spt3 (Table 2). Notably, eight of these nine positions are clustered over a small, 24-amino-acid span of Spt3 (337 amino acids in length). At three positions, M188, Y193, and W196, different amino acid changes were identified in different mutants. Of these nine positions in Spt3, most are highly conserved in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and human Spt3 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.—

Analysis of spt3 dominant-negative mutants. (A) Spot tests showing a dominant Spt− phenotype. Plasmids that contain the SPT3 alleles noted were used to transform strain FY374. Strains were grown under conditions selective for the plasmid (SC-Ura) to saturation and then dilutions were spotted onto SC-His-Ura plates to test the Spt− phenotype and onto SC-Ura plates as a control. The Spt− phenotype tested is suppression of his4-917 from His− to His+. Shown is growth after three days of incubation at 30°. (B) Conservation over the Spt dominant-negative region. Shown are the Spt3 sequences for S. cerevisiae, S. pombe, and Homo sapiens. The positions of the Spt3 dominant-negative changes are noted in the S. cerevisiae sequence by bold and underline. Symbols below the sequences indicate the degree of conservation: *, identical; :, highly similar; and ·, similar.

TABLE 2.

Dominant-negative spt3 mutations

| spt3 allelea | Predicted amino acid changeb | Strength of phenotypec |

|---|---|---|

| spt3-143 | W143R | Strong |

| spt3-178 | L178R | Strong |

| spt3-179 | K179E | Strong |

| spt3-182 | D182G (2×) | Strong |

| spt3-188 | M188V (2×) | Medium |

| spt3-189 | M188T | Strong |

| spt3-190 | M188I | Strong |

| spt3-193 | Y193C | Strong |

| spt3-194 | Y193F | Strong |

| spt3-195 | Y193H | Strong |

| spt3-196 | W196R | Strong |

| spt3-197 | W196C | Strong |

| spt3-201 | Q201P | Strong |

| spt3-204 | A202V | Strong |

The allele number corresponds to the codon altered except in cases of multiple changes in the same codon or previous use of the allele number.

In cases of multiple isolates, the number of times isolated is shown in parentheses.

Strength reflects the degree of growth on SC-His medium, scored at 30° over 3 days.

Isolation of suppressors of an spt3 dominant-negative mutation identifies new spt15 mutations:

If the spt3 dominant-negative mutations impair an interaction with another factor, then the isolation and analysis of suppressor mutations might point toward the identity of such a factor. We therefore isolated suppressors of one of the strongest spt3 mutations, spt3-193. We used a strain in which the spt3-193 mutation had been integrated into the genome, replacing the wild-type SPT3 sequence. In this configuration, spt3-193 is fully recessive in diploids (data not shown), likely due to the lower level of expression from the SPT3 promoter compared to the GAL1 promoter. This strain displays strong mutant phenotypes; in particular, the spt3-193 mutant is His+ Lys− in a his4-917δ lys2-173R2 background and it is also Gal−.

Beginning with strains FY2006 and FY2007 (Table 1), both of which contain the his4-917δ and lys2-173R2 insertion mutations, suppressors of spt3-193 were selected and analyzed as described in materials and methods. Briefly, 200 Lys+ Gal+ revertants were selected and then screened for those that also became His−. Those candidates that suppressed all three phenotypes were then tested for dominance or recessiveness. We have focused our studies on 10 recessive, independent mutations that conferred the strongest phenotypes. These mutations were first tested for linkage to spt3-193. Tetrad analysis revealed that 6 of the mutations were tightly linked to spt3-193 and 4 were unlinked (data not shown).On the basis of our previous isolation of extragenic suppressors of spt3 that were in the SPT15 gene, the 4 unlinked suppressors were each tested for linkage to SPT15 and were shown to be tightly linked.

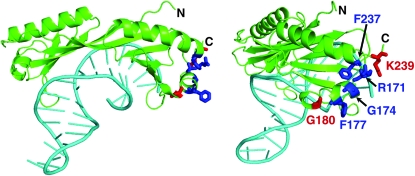

Each class of mutation was then subjected to DNA sequence analysis (materials and methods). For the six linked mutations, each one contained an identical second-site mutation in SPT3 that causes the predicted amino acid change E240K. This result was particularly surprising as the same mutation, named spt3-401, had been previously isolated as a suppressor of an spt15 mutation, spt15-21 (Eisenmann et al. 1992). Thus, spt3-401 can suppress either spt3-193 or spt15-21. For the four unlinked mutations, the SPT15 gene was completely sequenced. One mutant, named spt15-180, had two adjacent base pair changes, encoding a predicted amino acid change in TBP of G180Y. The other three mutants each had the identical spt15 mutation, causing the predicted amino acid change K239I. Previous studies have identified other changes at this position that affect interactions of TBP with Spt3, TFIIA, and TFIIB (Eisenmann et al. 1992; Buratowski et al. 2002). Interestingly, G180 and K239 are near one another in the structure of TBP and fall within a small region that contains four other TBP amino acids previously identified as important for functional interactions with Spt3 (Figure 2; (Eisenmann et al. 1992)).

Figure 2.—

Positions of amino acids altered by TBP mutants. (Left) The structure of yeast TBP and a TATA element (Kim et al. 1993) is shown. TBP is shown in green and the TATA DNA is shown in aqua. The two TBP mutants identified in this study cause changes at G180 and K239, shown in red, and previously identified changes (Eisenmann et al. 1992) occur at R171, G174, F177, and F237, and are shown in blue. (Right) The same structure rotated to provide a clearer view of the affected amino acids is shown. The figure was made using Polyview-3D (http://polyview.cchmc.org/polyview3d.html).

The spt3–spt15 interactions are allele specific:

To explore the nature of the genetic interactions between the new class of spt3 mutations and their spt15 suppressor mutations, several classes of double mutants were constructed and analyzed. First, we tested the ability of the new spt15 mutations, spt15-180 and spt15-239, to suppress spt3-196, another strong spt3 dominant-negative mutation. These results (Table 3) show that the suppression is allele specific, as spt3-196 is suppressed by only one of the two spt15 mutations. This result suggests that specific recognition is required between Spt3 and TBP for suppression.

TABLE 3.

Tests of allele specificity among new spt3 and spt15 mutations

| SPT3 allele | SPT15 allele | his4-917δ | lys2-173R2 | Suppression? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| spt3-193 | SPT15+ | + | — | |

| spt3-193 | spt15-180 | — | + | Yes |

| spt3-193 | spt15-239 | — | + | Yes |

| spt3-196 | SPT15+ | + | — | |

| spt3-196 | spt15-180 | — | + | Yes |

| spt3-196 | spt15-239 | + | — | No |

As a second test, we extended the analysis of the new spt3 and spt15 mutations to examine their interactions with a previously described pair of mutations, spt3-401 and spt15-21, that show allele-specific, mutual suppression (Eisenmann et al. 1992; Larschan and Winston 2001; Yu et al. 2003). To do this, we constructed several spt3–spt15 double mutant combinations between the new mutations and the two previously studied mutations. Our results (Table 4 and examples shown in Figure 3) demonstrate that a high degree of allele specificity extends to all of these mutants. With respect to spt3–spt15 genetic interactions, these results can be summarized as follows: (1) two sets of pairings of spt3 and spt15 mutations confer suppression (Table 4, lines 8, 9, and 14) and (2) combining spt3 and spt15 mutations from the different pairs often results in more severe phenotypes than observed in the single mutants (Table 4, lines 11–13). This is particularly evident for combinations of spt3-401 with spt15-180 and spt15-239, which individually have weak or undetectable phenotypes, but when combined have strong mutant phenotypes (Table 4, compare lines 3, 6, and 7 to lines 12 and 13; Figure 3). In addition, no interactions are observed between an spt3Δ (null) mutation and the spt15 mutations (Table 4, lines 15–17). Thus, distinct combinations of spt3 and spt15 mutations show either allele-specific suppression or allele-specific enhancement of mutant phenotypes.

TABLE 4.

Allele-specific interactions between old and new spt3 and spt15 mutations

| Relevant genotype | Gala | his4-917δb | lys2-173R2c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wild type | +d | − | + |

| 2. spt3-193 | −/+ | + | − |

| 3. spt3-401 | + | + | + |

| 4. spt3Δ | − | + | − |

| 5. spt15-21 | − | + | − |

| 6. spt15-180 | + | − | + |

| 7. spt15-239 | + | − | + |

| 8. spt3-193 spt15-180 | + | − | + |

| 9. spt3-193 spt15-239 | + | − | + |

| 10. spt3-193 spt3-401 | + | +/− | + |

| 11. spt3-193 spt15-21 | − | + | − |

| 12. spt3-401 spt15-180 | − | + | − |

| 13. spt3-401 spt15-239 | − | + | − |

| 14. spt3-401 spt15-21 | + | − | + |

| 15. spt3Δ spt15-180 | − | + | − |

| 16. spt3Δ spt15-239 | − | + | − |

| 17. spt3Δ spt15-21 | − | + | − |

The Gal phenotype was tested on YPgal plates containing antimycin A.

In strains with an otherwise wild-type background, his4-917δ confers a His− phenotype. Suppression was tested by spotting cells on SC-His medium.

In strains with an otherwise wild-type genotype, lys2-173R2 confers a Lys+ phenotype. Suppression was tested by spotting cells on SC-Lys medium.

Symbols indicate growth as follows: +, full growth of the spotted cells in one day; −, no growth or extremely poor growth; +/− and −/+, intermediate levels of growth.

Figure 3.—

Allele-specific interactions between spt3 and spt15 mutations. Spot tests showing the Spt− phenotype of spt3 and spt15 single mutants, and spt3 spt15 double mutants. Cells were grown as described for Figure 1 and spotted onto SC-His and YPD plates. Growth after 3 days of incubation at 30° is shown.

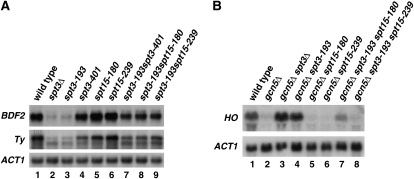

As Spt3 is required for normal transcription of particular genes in S. cerevisiae (Lee et al. 2000; Huisinga and Pugh 2004), we examined the new spt3 and spt15 mutants, as well as several mutant combinations, to determine their effects on transcription. To do this, we measured the mRNA levels for BDF2 and Ty1 elements, previously shown to be Spt3 dependent (Winston et al. 1984b; Bhaumik and Green 2002). Our results (Figure 4A) show that the mRNA levels of these Spt3-dependent genes strongly correspond to their Spt− phenotypes. Specifically, spt3-401, spt15-180, and spt15-239 all partially suppress the transcriptional defects of spt3-193. In addition, we examined mRNA levels for the HO gene, previously shown to be repressed by Spt3 in a gcn5Δ background (Yu et al. 2003). In this case (Figure 4B), our results again show that the allele-specific interactions are reflected at the transcriptional level. Given the multiple cases of allele specificity, these results suggest that Spt3 and TBP directly cooperate to control transcription at particular promoters in vivo.

Figure 4.—

Analysis of spt3-spt15 effects on transcription. (A) Suppression of activation defects in spt3-193 mutants. Northern analysis was performed to analyze the mRNA levels of BDF2 and of Ty1 elements. ACT1, whose mRNA levels are not affected by either the spt3 or spt15 mutations, serves as a loading control. (B) Suppression of repression defects in spt3-193 mutants. Northern analysis was performed to analyze the mRNA levels of HO.

The Spt3-Y193C mutant protein is defective for TBP recruitment even though it is present in SAGA:

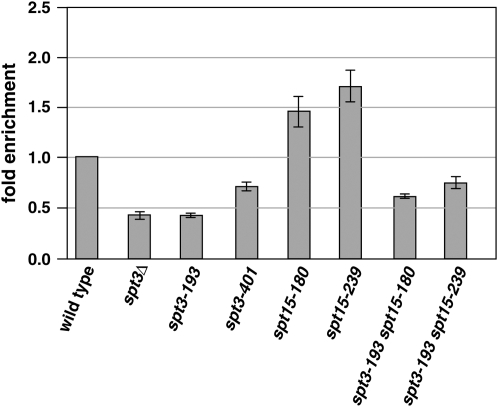

Previous studies have demonstrated that in an spt3 null mutant, the level of TBP recruitment to particular promoters is greatly diminished (Dudley et al. 1999a; Bhaumik and Green 2001, 2002; Larschan and Winston 2001). To test if the new class of spt3 mutants causes a similar defect, we measured TBP binding by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis in an spt3-193 mutant. Our results (Figure 5) show that, consistent with its transcriptional defect, an spt3-193 mutant has a reduced level of TBP associated with the BDF2 TATA region, equal to the reduction observed for an spt3 null mutant. Furthermore, in the spt3-193 spt15-180 and spt3-193 spt15-239 double mutants, the TBP binding defect is suppressed, although suppression by spt15-180 is modest. These results suggest that the product of spt3-193, Spt3-Y193C, is defective for TBP recruitment, but that this defect can be suppressed by compensating changes in TBP.

Figure 5.—

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of TBP binding at BDF2. The average and standard errors of three experiments are shown, with values normalized such that wild type = 1. The other calculated values are as follows: spt3Δ, 0.43 ± 0.07; spt3-193, 0.42 ± 0.04; spt3-401, 0.69 ± 0.09; spt15-180, 1.45 ± 0.31; spt15-239, 1.70 ± 0.32; spt3-193 spt15-180, 0.61 ± 0.04; and spt3-193 spt15-239, 0.75 ± 0.12.

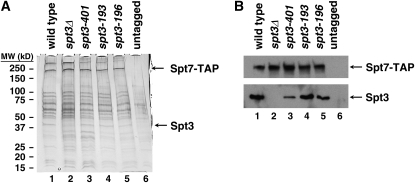

One obvious explanation for the TBP recruitment defect in the spt3-193 mutant is that the Spt3 mutant protein is either unstable or unable to assemble into SAGA, thereby mimicking an spt3 null mutant. To test this possibility, we purified SAGA from an spt3-193 mutant and tested for the presence of Spt3 in purified SAGA. We also tested a second strong spt3 mutant, spt3-196, which was also isolated in the dominant-negative screen. Our results (Figure 6) show that both mutant Spt3 proteins are present within SAGA at normal levels. The mutant defects, therefore, are not caused by an inability of Spt3 to assemble into SAGA.

Figure 6.—

Analysis of mutant Spt3 proteins in SAGA. SAGA was purified from the indicated strains using an SPT7-TAP allele (Wu and Winston 2002). (A) A silver-stained gel of purified SAGA from each strain. Indicated are the positions of Spt3 and Spt7. (B) Western analysis of Spt7 and Spt3 levels in SAGA purified from the indicated strains.

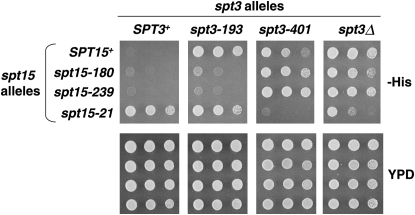

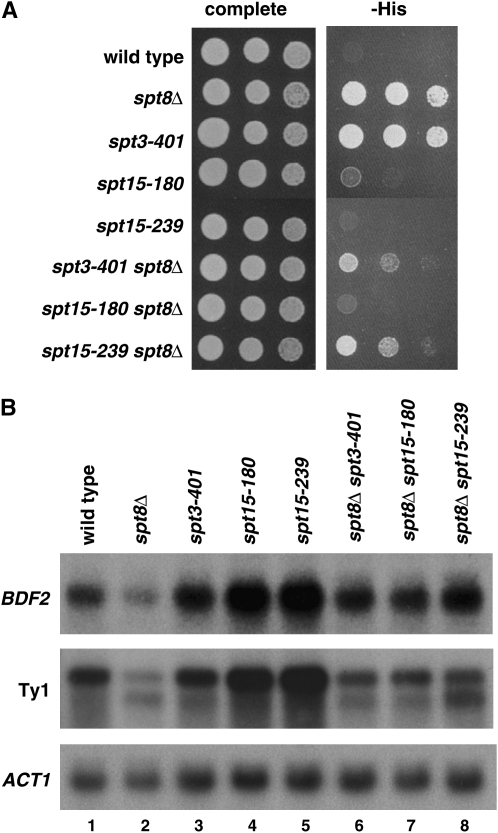

Both new spt15 mutations bypass spt8Δ:

Previous work showed that a mutation in SPT3, spt3-401, conferred suppression of an spt8Δ mutation (Eisenmann et al. 1994). To test if this might be true for any of the new spt3 or spt15 mutations isolated in this study, we combined spt3-193, spt15-180, and spt15-239 each with spt8Δ. Our results (Figure 7) show that both spt15-180 and spt15-239 confer suppression of spt8Δ, as measured by the Spt− phenotype (Figure 7A) and by transcriptional effects (Figure 7B). These results constitute the first demonstration that TBP mutants can bypass the requirement for Spt8. As described above, these spt15 mutations do not suppress spt3Δ; therefore, they are still Spt3 dependent, although they are partially Spt8 independent.

Figure 7.—

spt15 mutations can partially bypass loss of Spt8. (A) Spot tests to analyze suppression of spt8Δ by spt15 mutations with respect to the Spt− phenotype (suppression of his4-917δ) are shown. Growth after 3 days of incubation at 30° is shown. (B) Northern analysis to analyze suppression of spt8Δ by spt15 mutations.

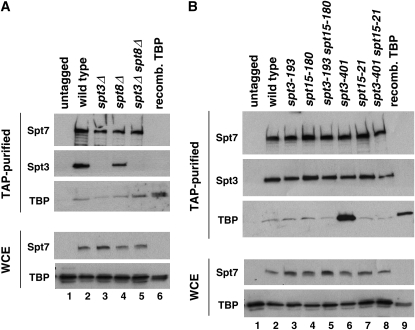

The level of the TBP–SAGA association is increased in an spt3-401 mutant:

Previous studies have shown that TBP can directly interact with SAGA in vitro (Sterner et al. 1999; Warfield et al. 2004; Sermwittayawong and Tan 2006) and have suggested direct interactions in vivo (Eisenmann et al. 1992; Lee and Young 1998; Roberts and Winston 1997; Saleh et al. 1997; Sanders et al. 2002). To test whether any of the spt3, spt8, or spt15 mutations analyzed in this work affect the level of this interaction, we purified SAGA in wild-type and several mutant strains and then determined the level of TBP that copurified. Our results (Figure 8) show that, as previously shown, a low level of TBP copurifies with SAGA (Saleh et al. 1997; Sanders et al. 2002) (Figure 8A, lane 2; Figure 8B, lane 2). Furthermore, this level of copurification is not significantly altered in spt3Δ, spt8Δ, and spt3Δ spt8Δ mutants (Figure 8A). When we examined other mutants, however, we observed that one mutation, spt3-401, unexpectedly causes a large increase in the level of the TBP–SAGA association (Figure 8B, lane 6). In an spt3-401 spt15-21 double mutant, which has a wild-type phenotype, there is a normal level of SAGA–TBP association. In conclusion, this assay suggests that neither Spt3 nor Spt8 is required for SAGA–TBP interactions in vivo, although a particular change in Spt3 can increase this interaction.

Figure 8.—

Analysis of TBP levels that copurify with SAGA. (A) Western analyses of purified SAGA from the indicated strains to analyze the level of TBP that copurifies in the indicated deletion mutants (top). Recombinant TBP serves as a marker for positive identification of TBP. (Bottom) Western analyses of the whole-cell extracts (WCE) to monitor the level of SAGA (by Spt7 levels) and TBP in each strain are shown. (B) Shown is analysis of spt3 and spt15 mutants to measure the level of TBP associated with purified SAGA. Panels are similar to those shown in A.

DISCUSSION

By a series of mutant isolations and analyses, we have found new evidence for a direct role of Spt3 in helping TBP to function in transcription in vivo. First, we have isolated dominant-negative mutations in SPT3 that cluster within a conserved region of the gene. Second, the isolation of suppressors of one of these spt3 mutations has identified spt15 mutations that interact with spt3 mutations in an allele-specific fashion. Third, we show that the newly isolated spt15 mutations partially bypass a null mutation in SPT8. Finally, we show that one spt3 mutation, spt3-401, causes a greatly increased level of SAGA–TBP interaction. The allele-specific interactions between spt3 and spt15 mutations, the ability of spt15 mutations to bypass spt8Δ but not spt3Δ, and the increased SAGA–TBP interactions in an spt3-401 mutant all support a model in which direct recognition between Spt3 and TBP is important for transcription in vivo.

Along the primary sequence of Spt3, four distinct regions have now been identified as important for functional interactions with TBP. Previous studies identified spt3 mutations that encode changes at positions 74, 240, and the termination codon (338) as suppressors of spt15-21 (Eisenmann et al. 1992) and our current studies identified changes in a fourth region, spanning amino acids 178–202. Based on the homology between Spt3 and human Taf11, and the structure of human Taf11 (Birck et al. 1998), most amino acids altered in our Spt3 mutants (with the exception of A202) lie on the same face of a putative α-helix. Furthermore, a model for Spt3 structure (Birck et al. 1998), suggests that these regions may conceivably exist near one another in the folded protein. Finally, given that the E240K change, encoded by spt3-401, significantly increases interactions with TBP, E240 may normally exist close to TBP, possibly in direct contact. Structural analysis of Spt3 is required to begin to understand the interactions of these regions in Spt3 with TBP.

In contrast to Spt3, the structure of TBP is well established and it is clear that the amino acid changes that we have identified contribute to a change of a specific region of TBP (Figure 2). Based on the clustering of these positions and the strong allele-specific interactions between spt3 and spt15 mutations, the simplest hypothesis is that this region of TBP directly interacts with Spt3. We cannot rule out other models in which Spt3 and TBP interact indirectly by altered interactions with other proteins, such as those in SAGA or other general transcription factors. For example, evidence exists for functional interactions of Spt3 with Mot1 (Collart 1996; Madison and Winston 1997; Topalidou et al. 2004; Van Oevelen et al. 2005). Such a model does not easily explain the allele specificity that has been demonstrated between spt3 and spt15 mutations, however, including at the level of TBP recruitment (this work and Larschan and Winston 2001).

The model that Spt3 and TBP directly interact stands in contrast to biochemical analysis of SAGA–TBP interactions. One recent study that tested specifically for SAGA–TBP physical interactions, demonstrated that two SAGA subunits, Spt8 and Ada1, interact directly with TBP, with no evidence for Spt3–TBP contact (Sermwittayawong and Tan 2006). Those results are consistent with an earlier study that also found direct Spt8–TBP interactions (Warfield et al. 2004). The differences between the biochemical and genetic studies can be explained by two general classes of models. First, as stated above, Spt3 may not normally interact directly with TBP. Second, Spt3 may indeed interact directly with TBP, but the methods used have not been able to detect this interaction. One previous method used to detect SAGA–TBP interactions in vitro used TBP conjugated with Sulfo-SBED, a photoactivatable lysine-specific reagent that can transfer biotin from the donor molecular to a nearby protein (Sermwittayawong and Tan 2006). Such an experiment requires that the conjugated lysine in TBP be nearby Spt3; however, the only lysine in the region of TBP believed to interact with Spt3 is K239, a position that is known to be important for normal Spt3–TBP interactions (Eisenmann et al. 1992). Therefore, the conjugation of Sulfo-SBED at K239 might impair Spt3–TBP interactions. Additional types of biochemical studies are necessary to definitively resolve the issue of whether Spt3 and TBP normally interact directly.

The spt3-401 mutation has several properties of interest, as we have shown that it increases SAGA–TBP interactions and suppresses spt3-193, in addition to past findings that it suppresses spt15-21 (Eisenmann et al. 1992) and spt8Δ (Eisenmann et al. 1994). Based on these results, the simplest hypothesis is that the Spt3-E240K mutant encoded by spt3-401 confers increased affinity between Spt3 and TBP and that this increased affinity overcomes particular defects in either TBP or Spt3, or loss of Spt8. The spt3-401 mutation also causes a modest Spt− phenotype. One possible reason for this defect can be explained by a recently proposed “handoff” model for SAGA function, in which TBP is initially recruited by SAGA and then transferred to bind to a TATA element (Sermwittayawong and Tan 2006). By this model, the increased Spt3–TBP interaction in spt3-401 mutants might impair the handoff, thereby reducing the level of TBP at particular TATA elements. Such a defective handoff might also cause a decreased level of TBP at some promoters, as assayed by ChIP, because TBP is strongly interacting with SAGA, which is associated at the UAS and therefore not bound to a TATA element to the same level. Alternatively, the increased level of Spt3–TBP interactions might sequester either protein from additional interactions, leading to a mutant phenotype. Consistent with this possibility, recent work has suggested a role for Spt3 outside of SAGA (James et al. 2007). As spt3-401 does not cause strong mutant phenotypes in an otherwise wild-type background, the increased SAGA–TBP interactions must not significantly alter TBP–TATA interactions. Interestingly, previous studies identified a mammalian TBP mutant that causes both increased TBP–TAF11 interactions and defective transcriptional activation (Lavigne et al. 1999). The altered amino acid changes in this human TBP mutant, L270 and E271, correspond to amino acids L172 and E173 in S. cerevisiae TBP, precisely within the region identified by our spt15 mutations.

Overall, the mechanism by which SAGA recruits TBP to promoters remains unresolved; however, current evidence suggests that a number of SAGA components contribute to this activity. Our work has established a strong functional requirement for Spt3. Given that both Spt3 and TBP mutants are able to partially bypass the need for Spt8 and that spt8Δ causes weaker phenotypes than spt3Δ (Eisenmann et al. 1994; Roberts and Winston 1996; Bhaumik and Green 2002), Spt3 may play a more primary role than Spt8 in the SAGA–TBP relationship. Spt8 is also required for TBP recruitment at many promoters, however, and it has been clearly demonstrated that Spt8 interacts directly with TBP (Bhaumik and Green 2002; Warfield et al. 2004; Sermwittayawong and Tan 2006). One study suggests that Spt8 is necessary for SAGA–TBP interactions (Sterner et al. 1999), while others suggest that additional factors may contribute, including Spt3, Ada1, and Ada2 (Barlev et al. 1995; Sermwittayawong and Tan 2006). The resolution to the question of the mechanism by which SAGA interacts to recruit TBP to TATA elements must await additional biochemical and structural analyses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Buratowski, Brad Cairns, Martine Collart, and Greg Prelich for antibodies and Karen Arndt for advice on the TBP ChIP experiments. We also thank Song Tan for pointing out that the Spt3 mutants alter one face of a putative helix and for other helpful comments on the manuscript. D.R. was supported by a fellowship from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was supported by NIH grant GM-45720 to F.W.

References

- Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman et al., 1991. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience, New York.

- Barlev, N. A., R. Candau, L. Wang, P. Darpino, N. Silverman et al., 1995. Characterization of physical interactions of the putative transcriptional adaptor, ADA2, with acidic activation domains and TATA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 19337–19344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belotserkovskaya, R., D. E. Sterner, M. Deng, M. H. Sayre, P. M. Lieberman et al., 2000. Inhibition of TATA-binding protein function by SAGA subunits Spt3 and Spt8 at Gcn4-activated promoters. Mol. Cell Biol. 20: 634–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik, S. R., and M. R. Green, 2001. SAGA is an essential in vivo target of the yeast acidic activator Gal4p. Genes Dev. 15: 1935–1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik, S. R., and M. R. Green, 2002. Differential requirement of SAGA components for recruitment of TATA-box-binding protein to promoters in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 22: 7365–7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birck, C., O. Poch, C. Romier, M. Ruff, G. Mengus et al., 1998. Human TAF(II)28 and TAF(II)18 interact through a histone fold encoded by atypical evolutionary conserved motifs also found in the SPT3 family. Cell 94: 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, D., Y. Yu, M. Prall, T. Formosa and D. J. Stillman, 2005. The yeast FACT complex has a role in transcriptional initiation. Mol. Cell Biol. 25: 5812–5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, J. E., J. Zhou, T. Ranalli, R. Kobayashi, D. G. Edmondson et al., 1996. Tetrahymena histone acetyltransferase A: a homolog to yeast Gcn5p linking histone acetylation to gene activation. Cell 84: 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratowski, R. M., J. Downs and S. Buratowski, 2002. Interdependent interactions between TFIIB, TATA binding protein, and DNA. Mol. Cell Biol. 22: 8735–8743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabal, G. G., A. Genovesio, S. Rodriguez-Navarro, C. Zimmer, O. Gadal et al., 2006. SAGA interacting factors confine sub-diffusion of transcribed genes to the nuclear envelope. Nature 441: 770–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart, M. A., 1996. The NOT, SPT3, and MOT1 genes functionally interact to regulate transcription at core promoters. Mol. Cell Biol. 16: 6668–6676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, J. A., and P. A. Grant, 2007. Multi-tasking on chromatin with the SAGA coactivator complexes. Mutat. Res. 618: 135–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, J. A., M. S. Torok, Z. W. Sun, D. Schieltz, C. D. Allis et al., 2004. Deubiquitination of histone H2B by a yeast acetyltransferase complex regulates transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 1867–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, A. M., L. J. Gansheroff and F. Winston, 1999. a Specific components of the SAGA complex are required for Gcn4- and Gcr1- mediated activation of the his4–912delta promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 151: 1365–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, A. M., C. Rougeulle and F. Winston, 1999. b The Spt components of SAGA facilitate TBP binding to a promoter at a post-activator-binding step in vivo. Genes Dev. 13: 2940–2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, D. M., K. M. Arndt, S. L. Ricupero, J. W. Rooney and F. Winston, 1992. SPT3 interacts with TFIID to allow normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 6: 1319–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, D. M., C. Chapon, S. M. Roberts, C. Dollard and F. Winston, 1994. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT8 gene encodes a very acidic protein that is functionally related to SPT3 and TATA-binding protein. Genetics 137: 647–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govind, C. K., F. Zhang, H. Qiu, K. Hofmeyer and A. G. Hinnebusch, 2007. Gcn5 promotes acetylation, eviction, and methylation of nucleosomes in transcribed coding regions. Mol. Cell 25: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, P. A., L. Duggan, J. Cote, S. M. Roberts, J. E. Brownell et al., 1997. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 11: 1640–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, K. W., A. Wyce, W. S. Lo, L. J. Duggan, N. C. Emre et al., 2003. Transcriptional activation via sequential histone H2B ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation, mediated by SAGA-associated Ubp8. Genes Dev. 17: 2648–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskowitz, I., 1987. Functional inactivation of genes by dominant negative mutations. Nature 329: 219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn, J. N., A. L. Bortvin, S. L. Ricupero-Hovasse and F. Winston, 1995. A new class of histone H2A mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae causes specific transcriptional defects in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 15: 1999–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisinga, K. L., and B. F. Pugh, 2004. A genome-wide housekeeping role for TFIID and a highly regulated stress-related role for SAGA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 13: 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, N., E. Landrieux and M. A. Collart, 2007. A SAGA-independent function of SPT3 mediates transcriptional deregulation in a mutant of the Ccr4-Not complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 177: 123–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y., J. H. Geiger, S. Hahn and P. B. Sigler, 1993. Crystal structure of a yeast TBP/TATA-box complex. Nature 365: 512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, A., P. Pascual-Garcia, A. Llopis, M. Zapater, F. Posas et al., 2006. The mRNA export factor Sus1 is involved in Spt/Ada/Gcn5 acetyltransferase-mediated H2B deubiquitinylation through its interaction with Ubp8 and Sgf11. Mol. Biol. Cell 17: 4228–4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarnitsky, P., E. J. Cho and S. Buratowski, 2000. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 14: 2452–2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larschan, E., and F. Winston, 2001. The S. cerevisiae SAGA complex functions in vivo as a coactivator for transcriptional activation by Gal4. Genes Dev. 15: 1946–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne, A. C., Y. G. Gangloff, L. Carre, G. Mengus, C. Birck et al., 1999. Synergistic transcriptional activation by TATA-binding protein and hTAFII28 requires specific amino acids of the hTAFII28 histone fold. Mol. Cell Biol. 19: 5050–5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. I., and R. A. Young, 1998. Regulation of gene expression by TBP-associated proteins. Genes Dev. 12: 1398–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. I., H. C. Causton, F. C. Holstege, W. C. Shen, N. Hannett et al., 2000. Redundant roles for the TFIID and SAGA complexes in global transcription. Nature 405: 701–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison, J. M., and F. Winston, 1997. Evidence that Spt3 functionally interacts with Mot1, TFIIA, and TATA- binding protein to confer promoter-specific transcriptional control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 17: 287–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, E., 2002. Multi-protein complexes in eukaryotic gene transcription. Plant Mol. Biol. 50: 925–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengus, G., M. May, X. Jacq, A. Staub, L. Tora et al., 1995. Cloning and characterization of hTAFII18, hTAFII20 and hTAFII28: three subunits of the human transcription factor TFIID. EMBO J. 14: 1520–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, D., E. J. Parnell, J. W. Landon, Y. Yu and D. J. Stillman, 2006. SWI/SNF binding to the HO promoter requires histone acetylation and stimulates TATA-binding protein recruitment. Mol. Cell Biol. 26: 4095–4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlrad, D., R. Hunter and R. Parker, 1992. A rapid method for localized mutagenesis of yeast genes. Yeast 8: 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar, A. M., B. D. Lemon and R. Tjian, 2001. Transcriptional coactivator complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70: 475–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pray-Grant, M. G., D. Schieltz, S. J. McMahon, J. M. Wood, E. L. Kennedy et al., 2002. The novel SLIK histone acetyltransferase complex functions in the yeast retrograde response pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 22: 8774–8786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut, G., A. Shevchenko, B. Rutz, M. Wilm, M. Mann et al., 1999. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 17: 1030–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. M., and F. Winston, 1996. SPT20/ADA5 encodes a novel protein functionally related to the TATA- binding protein and important for transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 16: 3206–3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. M., and F. Winston, 1997. Essential functional interactions of SAGA, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex of Spt, Ada, and Gcn5 proteins, with the Snf/Swi and Srb/mediator complexes. Genetics 147: 451–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Navarro, S., T. Fischer, M. J. Luo, O. Antunez, S. Brettschneider et al., 2004. Sus1, a functional component of the SAGA histone acetylase complex and the nuclear pore-associated mRNA export machinery. Cell 116: 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M. D., F. Winston and P. Hieter, 1990. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Saleh, A., V. Lang, R. Cook and C. J. Brandl, 1997. Identification of native complexes containing the yeast coactivator/repressor proteins NGG1/ADA3 and ADA2. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 5571–5578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, S. L., J. Jennings, A. Canutescu, A. J. Link and P. A. Weil, 2002. Proteomics of the eukaryotic transcription machinery: identification of proteins associated with components of yeast TFIID by multidimensional mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell Biol. 22: 4723–4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sermwittayawong, D., and S. Tan, 2006. SAGA competes with DNA to bind TBP via the Spt8 subunit: a handoff model for SAGA recruitment of TBP to the core promoter. EMBO J. 25: 3791–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirra, M. K., S. E. Rogers, D. E. Alexander and K. M. Arndt, 2005. The Snf1 protein kinase and Sit4 protein phosphatase have opposing functions in regulating TATA-binding protein association with the Saccharomyces cerevisiae INO1 promoter. Genetics 169: 1957–1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, A., N. Stanojevic, Z. Duan, P. Sen and S. R. Bhaumik, 2006. Ubp8p, a histone deubiquitinase whose association with SAGA is mediated by Sgf11p, differentially regulates lysine 4 methylation of histone H3 in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 26: 3339–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner, D. E., P. A. Grant, S. M. Roberts, L. J. Duggan, R. Belotserkovskaya et al., 1999. Functional organization of the yeast SAGA complex: distinct components involved in structural integrity, nucleosome acetylation, and TATA-binding protein interaction. Mol. Cell Biol. 19: 86–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner, D. E., R. Belotserkovskaya and S. L. Berger, 2002. SALSA, a variant of yeast SAGA, contains truncated Spt7, which correlates with activated transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 11622–11627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, M. S., and F. Winston, 1992. SPT4, SPT5 and SPT6 interactions: effects on transcription and viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132: 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, M. S., E. A. Malone and F. Winston, 1991. SPT5, an essential gene important for normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encodes an acidic nuclear protein with a carboxy-terminal repeat. Mol. Cell Biol. 11: 3009–3019 (erratum: Mol. Cell Biol. 11: 4286). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers, H. T., and L. Tora, 2005. SAGA unveiled. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30: 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalidou, I., M. Papamichos-Chronakis, G. Thireos and D. Tzamarias, 2004. Spt3 and Mot1 cooperate in nucleosome remodeling independently of TBP recruitment. EMBO J. 23: 1943–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oevelen, C. J., H. A. van Teeffelen and H. T. Timmers, 2005. Differential requirement of SAGA subunits for Mot1p and Taf1p recruitment in gene activation. Mol. Cell Biol. 25: 4863–4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfield, L., J. A. Ranish and S. Hahn, 2004. Positive and negative functions of the SAGA complex mediated through interaction of Spt8 with TBP and the N-terminal domain of TFIIA. Genes Dev. 18: 1022–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston, F., D. T. Chaleff, B. Valent and G. R. Fink, 1984. a Mutations affecting Ty-mediated expression of the HIS4 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 107: 179–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston, F., K. J. Durbin and G. R. Fink, 1984. b The SPT3 gene is required for normal transcription of Ty elements in S. cerevisiae. Cell 39: 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston, F., C. Dollard, E. A. Malone, J. Clare, J. G. Kapakos et al., 1987. Three genes are required for trans-activation of Ty transcription in yeast. Genetics 115: 649–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston, F., C. Dollard and S. L. Ricupero-Hovasse, 1995. Construction of a set of convenient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are isogenic to S288C. Yeast 11: 53–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P. Y., and F. Winston, 2002. Analysis of Spt7 function in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SAGA coactivator complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 22: 5367–5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P. Y., C. Ruhlmann, F. Winston and P. Schultz, 2004. Molecular architecture of the S. cerevisiae SAGA complex. Mol. Cell 15: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyce, A., T. Xiao, K. A. Whelan, C. Kosman, W. Walter et al., 2007. H2B ubiquitylation acts as a barrier to Ctk1 nucleosomal recruitment prior to removal by Ubp8 within a SAGA-related complex. Mol. Cell 27: 275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y., P. Eriksson, L. T. Bhoite and D. J. Stillman, 2003. Regulation of TATA-binding protein binding by the SAGA complex and the Nhp6 high-mobility group protein. Mol. Cell Biol. 23: 1910–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]