Abstract

National and international codes of research conduct have been established in most industrialized nations to ensure greater adherence to ethical research practices. Despite these safeguards, however, traditional research approaches often continue to stigmatize marginalized and vulnerable communities. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) has evolved as an effective new research paradigm that attempts to make research a more inclusive and democratic process by fostering the development of partnerships between communities and academics to address community-relevant research priorities. As such, it attempts to redress ethical concerns that have emerged out of more traditional paradigms. Nevertheless, new and emerging ethical dilemmas are commonly associated with CBPR and are rarely addressed in traditional ethical reviews. We conducted a content analysis of forms and guidelines commonly used by institutional review boards (IRBs) in the USA and research ethics boards (REBs) in Canada. Our intent was to see if the forms used by boards reflected common CBPR experience. We drew our sample from affiliated members of the US-based Association of Schools of Public Health and from Canadian universities that offered graduate public health training. This convenience sample (n = 30) was garnered from programs where application forms were available online for download between July and August, 2004. Results show that ethical review forms and guidelines overwhelmingly operate within a biomedical framework that rarely takes into account common CBPR experience. They are primarily focused on the principle of assessing risk to individuals and not to communities and continue to perpetuate the notion that the domain of “knowledge production” is the sole right of academic researchers. Consequently, IRBs and REBs may be unintentionally placing communities at risk by continuing to use procedures inappropriate or unsuitable for CBPR. IRB/REB procedures require a new framework more suitable for CBPR, and we propose alternative questions and procedures that may be utilized when assessing the ethical appropriateness of CBPR.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, Ethical dilemmas, Ethical issues in CBPR, Research ethics, Vulnerable communities

INTRODUCTION

Health research has had its dark moments. The Nazi Eugenic Experiments and the Tuskegee Syphilis Trials are but two infamous instances of abusive research behavior conducted in the name of “good science.”1–5 These examples remind us of an era when control of research lay in the hands of scientists whose principal goal was the advancement of knowledge; human costs were secondary.

As a result of these abuses, the Nuremberg code,6 and later the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki,7 developed a framework for the “ethical treatment of human subjects” in research. Today, most industrialized nations have sophisticated systems to protect subjects (or participants) in research. A fundamental requirement is that an ethical review be conducted on all publicly funded research—see, for example, the Belmont Report8 and the Tri-Council of Canada.9

Ethical guidelines generally use autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice as touchstone principles for conducting an “ethical review.”8,9 Respect for autonomy is based on one’s right to self-determination. Generally, this is operationalized through “informed consent.” Participants are seen as free agents who must be informed about the purpose of the research, the possible harms and benefits associated with participating, confidentiality and privacy procedures, how the data will be used, participant rights and responsibilities, and withdrawal procedures should participants ever wish to withdraw.9 Once potential participants fully understand the scope and purpose of the research, they are considered enabled to make an “informed” decision about whether to participate. Nonmaleficence (the principle of “doing no harm”) and beneficence (the “obligation to do good”) often operate on a continuum and are operationalized through processes of “minimizing harm” and “maximizing good” in research. Research procedures that knowingly harm individual participants are always unacceptable. Finally, the principle of justice means that all members of society should assume their fair share of both benefits and burdens of health research. It is unacceptable to coercively target vulnerable groups (e.g., prisoners) or, without good reason, to ban a whole group (e.g., women) from studies that might benefit them. In short, these guidelines maintain that morally acceptable ends and means should guide all research methodologies and processes.9

Still, ethical problems continue in health research. In particular, a focus on “individual ethics” has left some communities vulnerable to risks such as research conducted to advance academic careers at the expense of communities; wasting resources by selecting community-inappropriate methodologies;10,11 communities feeling overresearched, coerced, or misled;12 researchers stigmatizing communities by releasing sensitive data without prior consultation; and communities feeling further marginalized by research.10 Finally, a particularly damaging effect of traditional research is that researchers often do not give back to communities. Most egregiously, findings are not shared with community members. More commonly, researchers do little to build capacity within communities. Some scholars have referred to this phenomenon as “helicopter research,” a term derived from the practice of researchers flying into and out of First Nations’ communities—arriving with surveys, taking data, and giving little, if anything, back.13

COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH: A NEW PARADIGM IN HEALTH RESEARCH

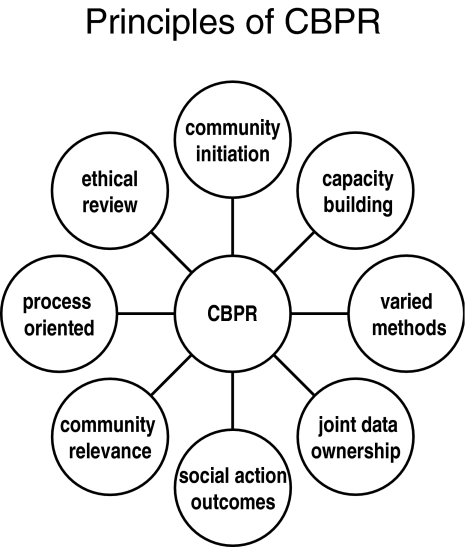

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is meant to address many of the problems associated with more traditional inquiry. Israel, Schulz, Parker, and Becker10 (p.184) coined the term to “emphasize the participation, influence and control by non-academic researchers in the process of creating knowledge and change.” Drawing on the traditions of action research,14–16 participatory action research,17–22 and participatory rural appraisals,23 CBPR has evolved as a popular new paradigm in health research.10,24–26 Many excellent reviews summarize the historical trajectory of CBPR and its key principles (see Figure 1).10,22,27 Drawing on the work of Israel and colleagues,10 the Kellogg Foundation Community Health Scholars Program27 succinctly captures the “democratizing” nature of CBPR:

CBPR is a collaborative approach to research that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings. CBPR begins with a research topic of importance to the community and has the aim of combining knowledge with action and achieving social change to improve health outcomes and eliminate health disparities.

FIGURE 1.

Principles of CBPR.

Paez-Victor28 argues that CBPR differs from more traditional forms of research by involving community members at the levels of “input” (communities initiate research ideas and projects), “process” (communities remain intimately engaged throughout data collection, analysis, and interpretation phases), and “outcome” (communities play significant roles in “mobilizing the knowledge attained in CBPR projects for social change.”) By involving community members as real and engaged partners, CBPR minimizes the likelihood of research that is irrelevant or insensitive to community concerns. The inclusive involvement of marginalized communities (such as youth) in research processes can produce more relevant results.29–33

CBPR recognizes communities as more than a grouping of individuals. Social networks can take on a life of their own, generating new subcultures with diverse collective needs. Urban centers in particular create unique challenges for their residents. Compared to their rural counterparts, urban-center dwellers are more likely to experience excess rates of a number of health and psychosocial outcomes, are more likely to be members of minority populations, and are more likely to be marginalized and disenfranchised from formal health systems.34 Minkler has argued that the intrinsic complexity of many urban health issues often makes them poorly suited to traditional research methods and interventions, suggesting instead that “CBPR can enrich and improve the quality and outcomes of urban health research in a variety of ways.”27 These include supporting the development of research questions that better reflect health issues of real concern to community members; improving researchers’ ability to achieve informed consent and address issues of costs and benefits to the community; improving the cultural sensitivity, reliability, and validity of measurement tools through high-quality community participation in designing and testing study instruments; and increasing the relevance of intervention approaches and thus the likelihood of success.

The first two authors of this paper have been extensively involved in CBPR capacity-building and funding initiatives in Toronto, Canada. Collectively, we have provided grants to, built capacities with, and worked closely with over 500 stakeholders in CBPR annually.35 We also are actively engaged in our own CBPR programs. We regularly hear complaints from members of vulnerable communities that they feel exploited by researchers. This has concerned us deeply in that this occurs as communities struggle to understand the role that research can play in helping them to improve quality of life. As they attempt to engage as equitable partners, they are constantly reminded that researchers’ priorities may differ fundamentally from theirs.

SHIFTING PARADIGMS

Several Canadian research communities have begun mandating that research conducted on their behalf must use a CBPR approach. Aboriginal and First Nations communities have taken the lead in codifying ownership, control, access, and possession as cornerstone values for all research involving them.12,36 The HIV/AIDS community-based movement has demanded that research be “democratized”37 and that academics share the privileged domain of “knowledge production” with community members (people living with HIV/AIDS and those who work with them and on their behalf). The blending of more traditional forms of knowledge production with “lived experience” has led to increasingly progressive and innovative methodologies. Besides bringing lived experience to more traditional forms of knowledge production, CBPR programs often pioneer new and exciting research methodologies such as Photovoice,38 concept mapping,39 and popular theater. While these are important steps forward, they may be unfamiliar to research ethics boards (REBs) trained in more traditional forms.

In response to community-level organizing, many high-profile funders have begun supporting CBPR initiatives. Some have increased the need for community representation within their existing grants and others have created CBPR streams. In Canada, these include The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ontario HIV Treatment Network, and the Wellesley Institute. In the USA, they include the National Institutes of Health, the National Institutes of Mental Health, the Centers for Disease Control, and the Kellogg Foundation. The criteria for these grants often include a high level of community involvement, diverse and community-sensitive research methods, and community- and policy-relevant outcomes. One overarching outcome stands apart: they have contributed to a cultural and paradigmatic shift in research through promoting initiatives that build capacities for community and academic partners to work collaboratively on CBPR initiatives.

BUT IS CBPR INHERENTLY “ETHICAL”?

Although sensitivity to the vulnerability of participants is implicit in CBPR, a different and perhaps unanticipated set of ethical issues may emerge.40–48 For instance, in creating a community-based advisory committee, a CBPR team may inadvertently cause conflict between community members.42,44,46 It is often difficult to find appropriate “community representatives” who will advocate on behalf of general community concerns.21,49,50 Sometimes it may be important to obtain consent at a “community” level from respected or elected community leaders.46,48,51 This may cause conflict when community leaders and members disagree on the importance of a research issue.

Moreover, when community members are equal partners in directing research programs, conflicts may be more likely to arise in relation to budgeting and payroll, deciding upon appropriate honoraria, and who is expected to volunteer their time.44,52,53 Despite ethical strictures to avoid creating coercive economic conditions (e.g., offering honoraria so high that economically disadvantaged persons may feel obliged to participate), it is also important to value and compensate all community members on a collaborative team for their time. Given the time and effort expended by community members on such teams, there may be an ethical imperative to ensure that equitable (or at the very least adequate) compensation exists for all team members.

Another potential issue is the balance between process and outcome.40,49,54 Because the very process of engaging in CBPR is meant to be transformative and empowering,17 it can be difficult to strike an appropriate balance between what needs to get done and the means. Research partners may find themselves having to ask “at what point do the needs of the many outweigh those of the few?”

Finally, ethical issues may arise in relation to disseminating or releasing sensitive or potentially unflattering data.40,42,44,45,48,51 Academic partners may feel an imperative to publish and to “stay true” to the “objective” nature of the data. Community members, however, may fear that unflattering data may (further) stigmatize their communities. Consequently, they may request that researchers consider the potential repercussions to the community if data are released prematurely or in an insensitive manner.45

An early review of CBPR in the Canadian HIV sector found many difficulties and inconsistencies in the ethical review process for research collaboratives.37 Despite considerable advances in CBPR in North America, REBs have been slow to adopt policies and procedures that would equip them to properly assess CBPR submissions.

METHODS

We conducted a content analysis of forms and guidelines used by institutional review boards (IRBs) in the USA and research ethics boards (REBs) in Canada. We drew our sample from affiliated members of the US-based Association of Schools of Public Health and from Canadian universities with graduate public health programs. Schools of public health were chosen because they have been some of the most receptive to CBPR methodologies—incorporating CBPR into their curricula, promoting student and faculty research with direct community linkages and outcomes, and including the approach in long-term planning.55–57 This convenience sample (n = 30) was garnered from programs with application forms available online for download between July and August, 2004. This sample reflected geographical diversity and included programs that supported CBPR in both countries (Table 1). Where available, social science or behavioral guidelines were given priority and downloaded from the university’s web site (when none were available, biomedical forms were downloaded).

TABLE 1.

IRB/REB forms reviewed

| Institution |

|---|

| Boston University School of Public Health, USA |

| George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services, USA |

| Harvard School of Public Health, USA |

| Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, USA |

| New York Medical College School of Public Health, USA |

| Ohio State University School of Public Health, USA |

| Saint Louis University School of Public Health, USA |

| Texas A&M School of Rural Public Health, USA |

| Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, USA |

| University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Dr. Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health, USA |

| University of California at Berkeley School of Public Health, USA |

| University of California at Los Angeles School of Public Health, USA |

| University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, USA |

| University of Kentucky College of Public Health, USA |

| University of Massachusetts School of Public Health and Health Sciences, USA |

| University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey—School of Public Health, USA |

| University of Michigan School of Public Health, USA |

| University of Minnesota School of Public Health, USA |

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Public Health, USA |

| University of North Texas Health Science Center School of Public Health, USA |

| University of Oklahoma College of Public Health, USA |

| University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, USA |

| University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health, USA |

| University of South Florida College of Public Health, USA |

| University of Texas School of Public Health, USA |

| University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine, USA |

| Yale University School of Public Health, USA |

| McGill University, Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Canada |

| University of British Columbia, Department of Health Care and Epidemiology, Canada |

| University of Toronto, Department of Public Health Sciences, Canada |

Based on the principles of CBPR and our collective experience in the field, we developed a template for the analysis to examine whether the ethics forms or guidelines queried community participation in the research process and reflected the other principles of CBPR (see Table 2). Reviewers were instructed to look for both key words and subjective intent. To promote reliability, each form was reviewed by the same two research assistants independently. The team then met to review results. When there was disagreement, an investigator reviewed the protocol with the two assistants and discussion ensued until consensus was reached.

TABLE 2.

REB/IRB Protocol content analysis

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Background | ||

| Does the form ask about the “scientific” rationale for the research (e.g., literature review)? | 30 | 0 |

| Does the form ask explicitly about community involvement in identifying the rationale for the research? | 0 | 30 |

| Research methodology | ||

| Is there a section on staff training and/or community capacity-building? | 0 | 30 |

| Are there questions that are concerned with minimizing barriers to community participation (e.g., that ask about language/ literacy issues, culturally sensitive methods/approaches etc.)? | 6 | 24 |

| Participants | ||

| Are there questions about protecting “vulnerable groups”? | 19 | 11 |

| Is there a justification section for sample selection (not just sample size, but inclusion and exclusion criteria)? | 16 | 14 |

| Conflicts of interest | ||

| Do forms explicitly ask about “power” relationships between researchers and participants? | 3 | 27 |

| Do forms ask about conflicts of interests (e.g., financial or otherwise) | 17 | 13 |

| Risks and benefits | ||

| Do forms ask about risks and benefits on an individual level? | 30 | 0 |

| Do forms ask about risks and benefits on a community/societal level? | 4 | 26 |

| Do the forms ask about how unflattering data might be handled? | 1 | 29 |

| Privacy and confidentiality | ||

| Do the forms ask about where data will be stored? | 20 | 10 |

| Do the forms ask about who has access to the data? | 18 | 12 |

| Do the forms ask about what training will be provided for those with access to sensitive data? | 5 | 25 |

| Compensation and budget | ||

| Do the forms ask about who is managing the budget? | 5 | 25 |

| Do the forms ask about who is getting compensated for their time (and how)? | 16 | 14 |

| Do the forms ask for a budget justification (e.g., what resources are in place to minimize barriers to participation such as childcare, food, transportation etc.)? | 0 | 30 |

| Do the forms ask about equitable distribution of resources between community and institutional partners? | 0 | 30 |

| Do the forms ask about monetary values (particularly in relation to the potential for compensation to be seen as coercion)? | 13 | 17 |

| Informed consent | ||

| Is there a section on individual consent? | 30 | 0 |

| Do the forms ask about getting “informed consent” from marginalized groups? | 17 | 13 |

| Do the forms ask about “community” consent? | 0 | 30 |

| Do the forms ask how partners or advisory boards will define accountability or decision making structures? | 1 | 29 |

| Outcome and results | ||

| Do the forms ask how research results will be disseminated? | 5 | 25 |

| Do the forms ask about commitment to action and follow-up based on results? | 2 | 28 |

| Is there a process for vetoing publication or ending the study based on community concerns? | 0 | 30 |

RESULTS

Results are summarized in Table 2. All the forms reviewed asked for a scientific rationale or literature review to contextualize the research (n = 30). None explicitly queried community involvement in defining the research problem (n = 0). None asked about hiring practices or what community capacity-building opportunities there might be throughout the research process. A few protocols (n = 6) did ask researchers to address how they would minimize barriers to participation (e.g., culturally sensitive approaches or minimizing language/literacy barriers). The University of Massachusetts, Amherst (Amherst) IRB requires consent forms to be translated when non-English-speaking persons are expected to be included in the study. Yale University asks that, for non-English-speaking subjects, the researchers “fully explain provisions in place to ensure comprehension, as well as translated documents.” Johns Hopkins asks for translated material when consent is sought in a foreign language, and also advises researchers to give respondents appropriate time to consider the risk of participation, with the time allotted being proportional to the inherent risk of the study. George Washington University also explicitly asks that forms be translated for non-English-speaking participants.

Despite public documents using “justice” as a guiding framework, only 19 of 30 asked specifically about protecting vulnerable groups. Many of these were lists of “protected populations” (pregnant women, prisoners, elderly, young people, etc.) with room for explanation if needed (University of Minnesota, George Washington, University of Michigan Medical School, New Jersey School of Public Health). Yale’s School of Medicine provides one of the most comprehensive lists, including vulnerable groups as well as those requiring “special consideration.” The purpose of these questions is to identify vulnerable groups and provide an explanation of how the research team will minimize risk to group members.

Sixteen inquired about sample size. However, most were interested in the sample size calculations and none specifically asked for justifications about inclusion/exclusion criteria. That is, no regard was given to the potential harm caused by recruiting a large number of individuals or in asking them to participate in a study.

While over half are concerned with financial conflicts of interest (17/30), only three asked about potential “power” imbalances between researchers and participants. However, notions of relative power remain limited. For example, the University of Michigan Medical School asks about populations susceptible to coercion, such as patients, students, and employees of the investigator, and advises against “excessive levels of payment” to persons “economically and educationally deprived.” In fact, slightly over half (n = 16) inquired about compensation and notions of coercion. By contrast, few (n = 5) questioned who would be managing the budget. None asked about equitable distribution of resources or budget justifications. Such questions cannot account for the complexity of power differentials between researchers and participants. Perhaps most unfortunate, economic differences are often addressed by giving little or no incentives to either individual respondents or community representatives (e.g., the hosting organization or clinic where the research is conducted). This further disempowers individuals and communities by suggesting their time, energy, and resources may be of little worth, and they should participate simply because they have been invited.

All (n = 30) asked about individual consent processes. None (n = 0) asked about communal consent processes. Only 17 asked about special accommodations for marginalized or vulnerable groups. One inquired about community advisory governance issues. All protocol forms asked about risks and benefits associated with research participation for individual research participants, but only four had questions that alluded to broader community risks and benefits. Among these, the examples were framed broadly as “social,” rather than as community-level risks and benefits (Tulane University Health Sciences Center; Saint Louis University). The interests of society as a whole are not necessarily those of a specific community being studied. Research participants chosen as members of communities often participate to benefit their community in more ways than “the advancement of medical knowledge and/or possible benefit to future patients” (University of California, Los Angeles). Only one asked about how unflattering data might be handled, but this had more to do with adverse events in medical research than the potentially stigmatizing results of sociobehavioral research (Yale University).

Protocols were generally concerned with access and privacy. Twenty asked about data storage and 18 about data access, but only five asked about training provided for those with access to sensitive data. Yale University and Amherst require investigators and all personnel involved in the study who work with subjects or with data with identifiers to complete “human subjects protection” training, with Amherst requiring that proof of certification be attached to the protocol. George Washington requires proof of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 training.

Finally, and perhaps most disturbingly, only five had any questions about data dissemination. The Harvard School of Public Health asks how results will be used and if they will “be given to subjects or added to their medical records.” More broadly, the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey School of Public Health ask about “plans for disseminating results of the proposed project (to scientific community and/or the public).” Of those, two asked about a commitment to follow up or act on results. In terms of responsibility to individual subjects, Amherst “may require...that significant new findings developed during the course of the research which may relate to the subject’s willingness to continue participation will be provided to the subject.” None asked about procedures for terminating a study or vetoing publication based on community concerns. While several asked for annual updates, none were designed with the intent that CBPR protocols have flexible timelines because of their process-oriented nature.

DISCUSSION: WHEN PARADIGMS COLLIDE

Although REBs/IRBs use the principles of autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice, the adequacy or relevance of these standardized approaches is not well understood in relation to the assessment of CBPR projects. The guidelines typically used reflect biomedical ethical frameworks used to assess risk to “individuals” and not to “communities.” Consequently, they may not be as appropriate to alternative approaches to research, including CBPR. REBs/IRBs may unintentionally be allowing studies to proceed that are causing “unintentional” harm to communities.41,43,47,58

Procedures that cannot adequately capture the potential for harm to communities engaged in CBPR are obviously problematic. By not encouraging research teams to consider and problem-solve these potential minefields, IRBs/REBs may be unwittingly predisposing CBPR teams to not consider the full range of potential ethical issues. Furthermore, IRBs/REBs may be missing an opportunity to educate researchers not engaged in CBPR to consider the potential community impact of their studies. To be suitable for CBPR, IRB/REB procedures must be placed within a new paradigm that is not strictly biomedical focused and attends to individual and community risks in assessing potential harm.

What constitutes “risk” to an outsider may be part of everyday experience for individuals within a community. When IRBs/REBs decide what is acceptable, they may unknowingly perpetuate social exclusion and serve to silence individuals and their collective communities. This is not to suggest community rights should supersede those of individuals. Rather, within a community ethical framework, individuals retain the right to refuse, but community standards of fairness and equity must also be considered in the research process. As well, IRBs/REBs must understand risk to participants persists long after they have completed a survey or ended an interview. The outcomes of research can affect individuals and communities in far-reaching and unexpected ways.

When researchers and communities access funds designated for CBPR, they often meet resistance in ethical review. The design and methodology that garnered their funding may become the point of contention between the investigators and the IRB/REB. Researchers may be forced to change the scope of their study and to omit those factors that made the study community-relevant in the first place.37,43 Interestingly, in some cases, IRBs/REBs are rejecting studies that have received both scientific and community review. This poses a question: are IRBs/REBs best positioned to evaluate community risk when communities often have their own complex and elaborate criteria for deciding norms and acceptable boundaries?

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ETHICAL REVIEW

In keeping with the “social action” principle of CBPR, we sought to assist in the development of new guidelines that might benefit communities in the long run and the field of CBPR in the present. Three recommendations for enhancing the quality of CBPR ethical review are:

IRBs/REBs engaged in reviewing CBPR (and other community-based intervention) grants should be provided with basic training in the principles of CBPR.

IRBs/REBs should mandate that CBPR projects seeking ethical review must provide signed terms of reference or memoranda of understanding. These should clearly outline the goals of the project, principles of partnership, decision-making processes, roles and responsibilities of partners, and guidelines for how the partnership will handle and disseminate data.48,59

IRBs/REBs should require CBPR projects to document the process by which key decisions regarding research design were made and how the communities most affected were consulted.60

Ultimately, we propose the need for protocol forms that ground the potential ethical problems inherent in CBPR studies in a framework inclusive of assessment of risk to communities and other CBPR principles. IRBs/REBs have an important role to play in assuming the ethical challenges posed by CBPR, and if they are to prevent an ethical splintering – with CBPR researchers and communities finding their own means of ethical review – they must work closely with CBPR researchers and communities towards better integrating their needs. In Table 3, we provide some alternative ways of addressing the same issues found in current protocol forms, but with increased sensitivity to community interests.

TABLE 3.

Alternative ways of addressing the issues in current protocol forms

| Traditional questions | Potential new questions |

|---|---|

| Background, purpose, objectives | |

| Provide a description of the background, purpose, objectives and hypothesis for the research | How was the community involved or consulted in defining the need? |

| Who came up with the research objectives and how? | |

| Is this research really justified? Are there concrete action outcomes? | |

| Who benefits? How? | |

| Research methodology | |

| Describe exactly how the research will be carried out | How will the community be involved in the research? At what levels? |

| What training or capacity-building opportunities will you build in? | |

| Procedures to be used in the conduct of the research (e.g., interviews, questionnaires, chart reviews) | Will the methods used be sensitive and appropriate to various communities (consider literacy issues, language barriers, cultural sensitivities, etc.)? |

| State the period during which the procedures will be carried out and how long each will last and be specific about the number and frequency of the procedures | How will you balance scientific rigor and accessibility? |

| Participants | |

| Describe who the participants are and why they were selected | Are you really talking to the “right” people to get your questions answered appropriately (e.g., service providers, community members, leaders etc.)? |

| State the proposed “sample size”; i.e., how many people will be involved | How will the research team protect vulnerable groups? |

| Provide relevant inclusion/exclusion criteria | Will the research process include or engage marginalized or disenfranchised community members? How? |

| Describe any special issues with the proposed population, i.e., incompetent patients or minors | Is there a reason to exclude some people? Why? |

| Recruitment | |

| Describe how and by whom participants will be approached and recruited. Include copies of any recruiting materials (e.g., letters, advertisements, flyers, telephone scripts). State where participants will be recruited from (e.g., hospital, clinic, school) | What provisions have you put in place to ensure culturally-relevant and appropriate recruitment strategies and materials? |

| Provide a statement of the investigator’s relationship, if any, to the participants (e.g., treating physician, teacher) | Have you considered “power” relationships in your recruitment strategies (no coercion!)? |

| Who approaches people about the study and how? | |

| Risks and benefits | |

| List the anticipated risks and benefits to participants | What are the risks and benefits of the research for communities? For individuals? |

| Describe how the risks and benefits are balanced and explain what strategies are in place to minimize/manage any risks | Be honest about risks and consider how you will minimize them. |

| Privacy and confidentiality | |

| Provide a description of how privacy and confidentiality will be protected. Include a description of data maintenance, storage, release of information, access to information, use of names or codes, and destruction of data at the conclusion of the research; include information on the use of audio or video tapes | Where will you store data? Who will have access to the data? How? |

| What processes will you put in place to be inclusive about data analysis and yet maintain privacy of participants? | |

| What rules will you have for working with transcripts or surveys with identifying information? | |

| How do you maintain boundaries between multiple roles (e.g., researcher, counselor, peer)? | |

| Compensation | |

| Describe any reimbursements, remuneration or other compensation that will be provided to the participants, and the terms of this compensation | It is important to reimburse people for their time and honor their efforts; however, economic incentives should never become “coercive.” How will you approach compensation? |

| What provisions have you made for minimizing barriers to participation (e.g., providing for food, travel, childcare)? | |

| Who is managing the budget? How are these decisions negotiated? | |

| Conflicts of interest | |

| Provide information relevant to actual or potential conflicts of interest (to allow the review committee to assess whether participants require information for informed consent) | What happens when your job depends on the results? |

| What happens when you are the researcher and the friend, peer, service provider, doctor, nurse, social worker, educator, funder, etc. | |

| How will you appropriately acknowledge and negotiate power differentials? | |

| Informed consent process | |

| Provide a description of the procedures that will be followed to obtain informed consent | What does this mean for “vulnerable” populations (e.g., children, mentally ill, developmentally challenged)? |

| Include a copy of the information letter(s) and consent form(s) | What processes do you have in place for gathering individual consent? |

| Where written informed consent is not being obtained, explain why | What processes do you have in place for gathering community consent? |

| Where minors are to be included as participants, provide a copy of the assent script to be used | Are your consent processes culturally sensitive and appropriate for the populations that you are working with? |

| Outcomes and results | |

| N/A | How will the research be disseminated to academic audiences? |

| How will the research be disseminated to community audiences? | |

| What are the new ways that this research will be acted upon to ensure community/policy/social change? | |

| Ongoing reflection and partnership development | |

| N/A | Please attach a copy of your partnership agreement or memorandum of understanding signed by all partners that describes how you will work together. |

| What internal process evaluation mechanisms do you have in place? | |

| When your plans change to accommodate community concerns (as they invariably do in CBPR), how will you communicate this to the REB? | |

These suggested questions do not detract from individual ethical concerns, but serve to broaden the scope of risk assessment. They serve two potential purposes: (1) a guide to inform future research design (that can help research teams clarify conceptualizing new projects) and (2) a guide towards improved and more holistic ethics protocol review forms. While the role of designing and conducting ethical research is ultimately in the hands of investigators, IRBs/REBs provide an important framework to support ethical practises.

CONCLUSION

IRB/REB forms overwhelmingly operate within a traditional framework focused on assessing risk to individuals and not communities. They rarely take into account common CBPR experience. Their noninterest in community-level concerns, capacity building, and issues of equity situate them within a biomedical framework privileging “knowledge production” as the exclusive right of academic researchers. Furthermore, the lack of emphasis on action outcomes, dissemination, and decision-making processes is antithetical to the goals of CBPR.10 Failing to build the capacity of community groups to conduct/participate in/understand research after a formal arrangement with a researcher is over may leave communities vulnerable to exploitation in future research studies. Enhancing capacities during the research process diminishes the possibility of future researchers exploiting vulnerable communities and enhances the opportunities for communities to produce knowledge grounded in experience. In addition, if IRBs/REBs are not concerned with the action outcomes of research projects, they may be inadvertently heightening the risk of research studies “sitting on a shelf and collecting dust,” rendering potentially useful findings invisible and inaccessible.

Our intention in presenting an alternative is to suggest democratizing the process, and not the creation of additional bureaucratic barriers to engaging in CBPR. There are already more than enough obstacles. We address some glaring differences in approaches between traditional/biomedical and CBPR frameworks. In shedding light on these differences, we hope to inspire IRBs/REBs to consider developing alternative processes for reviewing CBPR—ethical reviews that take into account the unique issues and concerns commonly associated with the approach. Furthermore, we hope to inspire dialogue about the importance of addressing many of these questions as ethical concerns. To improve these conditions, IRB/REB members need to be empowered with the tools needed to effectively evaluate CBPR ethics protocols.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many community-based researchers who shared their problems and concerns with us. In addition, our gratitude goes to Meredith Minkler, Sarena Seifer, and the anonymous reviewers who gave us feedback to improve the manuscript. Finally, we are indebted to David Flicker for his editorial genius. This research was supported by the Wellesley Institute.

Footnotes

Flicker is with the Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Canada; Travers is with the Ontario HIV Treatment Network, Toronto, Canada; Guta is with the University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; McDonald is with the Community Based Research Resource Centre, Wellesley Institute, Toronto, Canada; Meagher is with the Mental Health Community Advisory Panel, St. Michael’s Hospital. Toronto, Canada.

References

- 1.Seidelman W. Nuremberg lamentation: for the forgotten victims of medical science. BMJ. 1996;313(7070):1463–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Pressel D. Nuremberg and Tuskegee: lessons for contemporary American medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(12):1216–1225. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Jones J. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. New York: Free Press; 1993.

- 4.Gamble V. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1999;87(11):1773–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Corbie-Smith G. The continuing legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study: considerations for clinical investigation. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317(1):5–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.The Nuremburg Code. “Permissible Medical Experiments.” Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10. Nuremberg October 1946 – April 1949. J Am Med Assoc. 1949;276(20):1691.

- 7.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects (last amended Oct 2000). World Medical Association; 1964. Available at: http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm. Accessed on: 15 Nov 2005.

- 8.Office of the Secretary. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research; 1979. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/belmont.htm. Accessed on: 15 Nov 2005. [PubMed]

- 9.Tri-Council of Canada. Tri-Council policy statement: Ethical conduct for research involving humans. Interagency Secretariat on Research Ethics on behalf of The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada; 1998. Available at: http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/english/pdf/TCPS%20October%202005_E.pdf. Accessed on: 15 Nov 2005.

- 10.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–194. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Whitehead M. The ownership of research. In: Davies JK, Kelly MP, eds. Healthy Cities: Research and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge; 1993:83–89.

- 12.Schnarch B. Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP) or Self-determination Applied to Research. A Critical Analysis of Contemporary First Nations Research and some Options for First Nations Communities. Ottawa: First Nations Centre, National Aboriginal Health Organization; 2004.

- 13.Struthers R, Lauderdale J, Nichols LA, Tom-Orme L, Strickland CJ. Respecting tribal traditions in research and publications: voices of five Native American nurse scholars. J Transcult Nurs. 2005;16(3):193–201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Lewin K. Action research and minority problems. J Soc Issues. 1946;2:34–46.

- 15.Lewin K. Resolving Social Conflicts. New York: Harper & Row; 1948.

- 16.Argyris C, Putnam R, McLain Smith D. Action Science. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc; 1985.

- 17.Gaventa J. The powerful, the powerless, and the experts: knowledge struggles in an information age. In: Park P, Brydon-Miller M, Hall B, Jackson T, eds. Voices of Change: Participatory Research in the United States and Canada. Toronto: The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education; 1993:21–40.

- 18.Friere P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Seabury Press; 1970.

- 19.Fals-Borda O, Anishur Rahman M. Action and Knowledge Breaking the Monopoly with Participatory Action Research. New York: The Apex Press; 1991.

- 20.Whyte WF, et al. Participatory Action Research. Newbury Park: SAGE; 1991.

- 21.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger D, et al. What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1929–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Cornwall A, Jewkes R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(12):1667–1676. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Chambers R. Whose Reality Counts? Putting the First Last. London: ITDG; 1997.

- 24.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health. 2001;14(2):182–197. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, No 99. AHRQ Publication 04-E022-1. Rockville: RTI-University of North Carolina Evidence Based Practice Center & Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl 2):ii3–ii12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003.

- 28.Paez-Victor M. Community-based Participatory Research: Community Respondent Feedback. In: 1st International Conference on Inner City Health, Toronto; 2002.

- 29.Harper G, Carver L. “Out-of-the-mainstream” youth as partners in collaborative research: exploring the benefits and challenges. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26(2):250–265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Travers R, Leaver C, McClelland A. Assessing HIV vulnerability among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual (LGBT) and 2-spirited youth who migrate to Toronto. Can J Infect Dis. 2002;13(Suppl A) Abstract # 408.

- 31.Carolo H, Travers R. Challenges, complexities and solutions: A unique HIV research partnership in Toronto, Canada. J Urban Health. 2005;82:ii42.

- 32.Flicker S, Skinner H, Veinot T, et al. Falling through the cracks of the big cities: who is meeting the needs of young people with HIV? Can J Public Health. 2005;96(4):308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Flicker S, Goldberg E, Read S, et al. HIV-positive youth’s perspectives on the Internet and e-health. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Higgins D, Metzler M. Implementing community-based participatory research centres in diverse urban settings. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):488–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Flicker S, Gierman N, Nayar R. Seeding Research: Sprouting Change. In: Poster Presentation 4th International Conference on Urban Health, Toronto, Canada; October 2005.

- 36.Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network. Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP). Available at: http://www.linkup-connexion.ca/catalog/prodImages/042805095650_314.pdf#search=%22CAAN%20OCAP%22. Accessed on: 3 Oct 2006.

- 37.Ogden R. Report on Research Ethics Review in Community-based HIV/AIDS Research. Vancouver: Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network under contract with AIDS Vancouver; 1999. Available at: http://cbr.cbrc.net/files/1029213009/Ogden%20Ethics%20Report.pdf. Accessed on: 22 Feb 2007.

- 38.Wang C, Redwood-Jones Y. Photovoice ethics: perspectives from flint photovoice. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(5):560–572. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Burke J, O’Campo P, Peak G, Gielen A, McDonnell K, Trochim W. An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research methodology. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(10):1392–1410. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Minkler M, Fadem P, Perry M, Blum K, Moore L, Rogers J. Ethical dilemmas in participatory action research: a case study from the disability community. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(1):14–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Khanlou N, Peter E. Participatory action research: considerations for ethical review. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(10):2333–2340. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Grossman D, Agarwal I, Biggs V, Brenneman G. Ethical considerations in research with socially identifiable population. Pediatrics. 2004;113:148–151. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Downie J, Cottrell B. Community-based research ethics review: reflections on experience and recommendations for action. Health Law Rev. 2001;10:8–17. [PubMed]

- 44.Brugge D, Kole A. A case study of community-based participatory research ethics: the healthy public policy initiative. Sci Eng Ethics. 2003;9:485–501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(6):684–697. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Marshall P, Rotimi C. Ethical challenges in community-based research. Am J Med Sci. 2001;322(5):241–245. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Firehook K. Protocol and Guidelines for Ethical and Effective Research of Community Based Collaborative Processes. Tuscun: Community Based Collaboratives Research Consortium; 2003.

- 48.Macaulay A, Delormier T, McComber A, Kirby R, Saad-Haddad C, Desrosiers S. Participatory research with native community of Kahnawake creates innovative code of research ethics. Can J Public Health. 1998;89(2):105–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Flicker S. Critical Issues in Community-based Participatory Research. Toronto: Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Toronto; 2005.

- 50.Jewkes R, Murcott A. Community representatives: representing the “community”? Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(7):843–858. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Serrano-Garcia I. Implementing research: putting our values to work. In: Tolan P, Keys C, Chertok F, Jason L, eds. Researching Community Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1990:171–182.

- 52.Borzekowski DLG, Ipp L, Diaz A, Rickert VI, Fortenberry JD. At what cost? The current state of participant payment in adolescent research. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(2):126–126. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Paradis EK. Feminist and community psychology ethics in research with homeless women. Am J Community Psychol. 2000;28(6):839–858. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.O’Toole T, Aaron K, Chin M, Horowitz C, Tyson F. Community-based participatory research: opportunities, challenges and the need for a common language. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:592–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Calleson D, Kauper-Brown J, Seifer S. Community-engaged Scholarship Toolkit. Seattle: Community–Campus Partnerships for Health; 2005.

- 56.Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences Press; 2002.

- 57.Seifer SD, Shore N, Holmes SL. Developing and Sustaining Community–University Partnerships for Health Research: Infrastructure Requirements. A Report to the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. Seattle: Community–Campus Partnerships for Health; 2003.

- 58.George A, Van Bibber M. Report to Vancouver Foundation of Ethical Review Framework for Community-based Research Vancouver. Vancouver: Vancouver Foundation (BC Medical Services Foundation) and The University of British Columbia; 2003.

- 59.Palermo A-G, McGranaghan R, Travers R. Unit 3: developing a CBPR partnership—creating the “glue”. In: The Examining Community–Institutional Partnerships for Prevention Research Group, ed. Developing and Sustaining Community-based Participatory Research Partnerships: A Skill-building Curriculum. Seattle: Community Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH); 2006. Available at: http://www.cbprcurriculum.info. Accessed on: 22 Feb 2007.

- 60.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Ethical Considerations for Research on Housing-related Health Hazards Involving Children. Report Brief. National Academy of Sciences; 2005. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/32/245/Housing%20Ethics%20web.pdf. Accessed on: 1 Nov 2006.