Abstract

The objective of this study is to compare the costs and benefits of a graded activity (GA) intervention to usual care (UC) for sick-listed workers with non-specific low back pain (LBP). The study is a single-blind, randomized controlled trial with 3-year follow-up. A total of 134 (126 men and 8 women) predominantly blue-collar workers, sick-listed due to LBP were recruited and randomly assigned to either GA (N = 67; mean age 39 ± 9 years) or to UC (N = 67; mean age 37 ± 8 years). The main outcome measures were the costs of health care utilization during the first follow-up year and the costs of productivity loss during the second and the third follow-up year. At the end of the first follow-up year an average investment for the GA intervention of €475 per worker, only €83 more than health care utilization costs in UC group, yielded an average savings of at least €999 (95% CI: −1,073; 3,115) due to a reduction in productivity loss. The potential cumulative savings were an average of €1,661 (95% CI: −4,154; 6,913) per worker over a 3-year follow-up period. It may be concluded that the GA intervention for non-specific LBP is a cost-beneficial return-to-work intervention.

Keywords: Costs–benefit analysis, Graded activity, Low back pain, Productivity loss, Sick-leave

Introduction

Work-related low back pain (LBP) is usually a benign, self-limiting condition which resolves spontaneously within a few weeks. The incidence and prevalence of work-related LBP are particularly high in industries characterized by manual labor [1, 3]. In a small subset of workers, work-related LBP may result in extended periods of work-absenteeism and greater utilization of health care services, two consequences which have a significant socio-economic impact [1, 6, 17, 18, 24]. The prevention of the occurrence of chronic LBP and the minimization of work-absenteeism is a common goal for workers, employers, policy makers and health care providers. Most economic evaluations have been performed from the societal perspective where all relevant costs are summed together without consideration for who actually pays. However, this approach has limited relevance for the company, where knowing who pays what is of critical interest and importance for decision-making [8, 16, 18, 23]. From the literature, it appears that the initiation of return-to-work interventions (RTW), such as graded activity (GA) during the sub-acute phase of LBP (4–6 weeks after the onset of work-absenteeism) may be promising [4]. For instance, the recent studies have shown that RTW interventions for sub-acute LBP are more effective in reducing short- and long-term absence from work than usual care (UC) [5, 7–10, 14–16, 21]. However, the available information about the costs and benefits of such interventions is still limited.

The aim of this study is to compare the long-term costs and benefits of a GA intervention for sub-acute work-related LBP to UC from the perspective of the employer.

Methods

Study design

The study design, the content of the GA intervention and clinical outcomes have been reported in detail elsewhere [21]. In short, the study was a single-blind, randomized controlled trial conducted at the Royal Dutch Airlines between April 1, 1999 and December 31, 2000. Sick-listed employees who had suffered LBP complaints for a minimum of 4 weeks were recruited by in-house occupational physicians and randomized by means of block randomization and stratification on the level of department to either UC or GA. All subjects received routine guidance from their occupational physician. In addition, the GA subjects followed twice a week a 60-min physical exercise session with a cognitive behavioral approach under the supervision of specifically trained physiotherapists. They stay on program until they fully returned to their previous duties, or until the maximum therapy duration of 3 months was reached. The UC subjects were permitted to seek and receive any type of treatment with the exception of a GA program.

Definitions and data collection

Sick-leave days, named as “lost productivity days (LPD),” were used as a proxy measure of productivity loss. Recurrences were defined as partial or full sick-leave due to LBP following a full return to work for at least 28 calendar days. Disabled workers were those who were completely or partially sick-listed for more than 52 weeks.

Baseline data included age, gender, job assignment, wage group and the number of sick-leave days due to the present episode of LBP accumulated before randomization. During all follow-up years, the recurrences of LBP, the total number of sick-leave days as well as the number of disabled workers were obtained from the electronic database of the occupational services. The health care utilization data were collected by means of cost diaries during the first follow-up year.

Economic evaluation

HCU costs were estimated using the Dutch guidelines for cost analysis in health care research. The unit prices of treatments and medications, were derived from the available tariffs publications [2, 19, 22].

The total LPD were quantified as gross and net ones. The number of gross LPD (GLPD) reflects the total number of calendar days that workers were completely or partially sick-listed. The partial LPD was counted for its percentage of work absence and expressed as net LPD (NLPD).

The cost of LPD of each worker was calculated by multiplying the mean daily wage increased by an additional 80% for secondary benefits. The costs of NLPD were recalculated after correction for a possible 25 or 50% decrease in productivity, because of the possibility that the workers may perform at a lower level than usual when they were partially recovered or were working in reassigned duty or in therapeutic position.

Data analysis

Non-cost data were analyzed using SPSS (version 11.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The economic evaluation was performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. The HCU costs and lost productivity costs were analyzed using a bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping method with 2,000 replications. The mean costs of HCU were analyzed for the entire study population after imputation of missing data via the hot deck method and after interpolation for non-observed months [20].

Results

Subjects

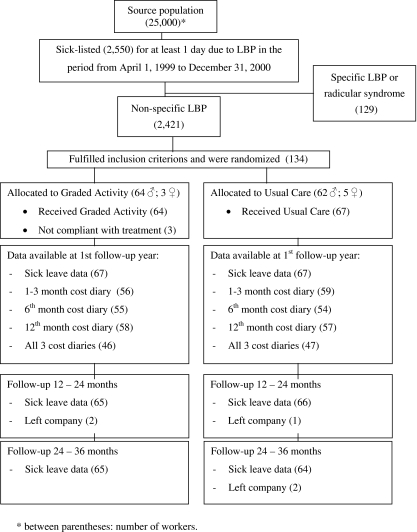

During the 21-month enrollment period, 150 workers were eligible to participate in the study. Ultimately, 134 employees were randomized to either UC (N = 67) or GA (N = 67). During the second follow-up year three subjects and in the third year another two subjects left the company and were lost to follow-up (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the participants and dropouts during the 3-year follow-up period. Asterisk indicates number of workers

Baseline measurements

As reported in detail elsewhere, there were no relevant between-group differences with respect to age, gender or job, nor in the mean number of GLPD and NLPD prior to randomization [21].

Health care utilization

The return rate of the cost diaries was 84% and there were 93 workers who returned all diaries (UC = 46; GA = 47). Non-responders did not significantly differ from responders in terms of baseline characteristics. The HCU data during the first year of follow-up are presented in Table 1. During the first 3 months, the GA subjects received significantly (P = 0.001) more physiotherapy than the UC. GA subjects attended an average of 13 GA sessions of 1 h duration, which is an equivalent to 26 (SD = 11) standard physiotherapy sessions of 30 min. UC subjects attended on average nine (SD = 9) standard physiotherapy sessions. However, in the subsequent months, the UC subjects attended a larger number of physiotherapy sessions, and by the end of the 12-month follow-up period, the difference between the groups was no longer significant.

Table 1.

Health care utilization (number of consultation, examinations or medications) during the first follow-up year

| Group | Consultations to general practitioner Mean (SD) |

Consultation occupational physician Mean (SD) |

CT scans and MRI scans Mean (SD) |

X-ray of lumbar back Mean (SD) |

Physiotherapy and paramedical therapy sessions Mean (SD) |

Consultations to specialist Mean (SD) |

Consultations to alternative therapist Mean (SD) |

Pain medication Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graded activity (N = 67) | 2.2 (4.1) | 3.9 (3.5) | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.5 (1.8) | 35.1 (21.9)a | 0.3 (1.2) | 0.7 (4.2) | 1.2 (2.1) |

| Usual care (N = 67) | 4.5 (6.9) | 4.8 (4.1) | 0.03 (0.2) | 0.4 (1.3) | 27.6 (48.7) | 0.3 (0.9) | 1.4 (5.6) | 1.6 (2.6) |

| P valueb | 0.008 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.86 | 0.25 | 0.94 | 0.38 | 0.32 |

aOne 60-min GA session is an equivalent to two standard 30-min physiotherapy sessions

bANOVA, level of significance P < 0.05

Lost productivity days and recurrences

The mean difference in the number of GLPD at each follow-up period was in absolute number of days in favor of the GA group. A similar pattern was observed for the NLPD (Table 2). During the 3-year follow-up 69% of UC subjects and 67% of GA subjects suffered a recurrence of work-absenteeism due to LBP. None of these differences was statistically significant.

Table 2.

Mean difference between GA group and UC group of gross and net lost productivity days and costs during 3 years of follow-up

| Follow-up period | Quantification | Mean difference of lost productivity days GA–UC (95% CI) | Mean difference of costs of lost productivity in 1999 € GA–UC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First year (N = 134) | Net | 9.1 (−14.8 to 31.5) | 999 (−1,073 to 3,115) |

| Gross | 40.4 (4.7 to 78.8) | 3,655 (157 to 6,933) | |

| Second year (N = 131) | Net | −1.1 (−24.6 to 24.5) | 118 (−2,079 to 2,541) |

| Gross | 12.1 (−27.6 to 49.7) | 1,522 (−2,315 to 5,126) | |

| Third year (N = 129) | Net | 2.8 (−15.6 to 20.7) | 467 (−1,173 to 2,207) |

| Gross | 13.3 (−24.7 to 50.1) | 1,685 (−1,673 to 5,623) | |

| Cumulative (N = 134) | Net | 12.0 (−50.2 to 64.9) | 1,661 (−4,154 to 6,913) |

| Gross | 79.2 (−23.8 to 192.3) | 7,581 (−3,262 to 17,348) |

Work-disabled employees

In the first follow-up year, 13 subjects (GA = 5; UC = 8) were deemed work-disabled due to LBP. By the end of the second follow-up year one additional worker from the GA group became work disabled. By the end of the third follow-up year the total number of work-disabled subjects had decreased to 11 (GA = 5; UC = 6) as one subject had found a higher paying position within the company, and two subjects had left the company and were lost to follow-up.

Cost–benefit analysis

The mean differences in HCU costs between groups were similar for complete case analysis and imputed case analysis. Therefore, only the results of the latter will be reported.

The mean total cost of the GA intervention was €475. During the first 3 months of follow-up, the HCU costs were higher in the GA than in the UC. In the same period, the UC group has spent less on physiotherapy and more on other medical services. At the end of the first year the average between-group difference in HCU costs was €83 (95% CI: −467; 251) lower in the UC, but not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean HCU costs, in 1999 €, and between-group differences during the first 3 months of follow-up and entire first year

| Follow-up | Group | Cost of GA intervention mean (SD)a | Cost of physiotherapy mean (SD)a | Difference in intervention costs (UC–GA) mean (SD)a | Other medical costs mean (SD)a | Difference in other medical costs (UC–GA) | Total health care costs mean (SD)a | Difference in total health care costs (UC–GA) mean (CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First 3 months | GA | 475 (203) | 0 | −307 | 26 (62) | 44 | 501 (215) | −263 (−346–−172) |

| UC | 0 | 168 (169) | 69 (89) | 238 (218) | ||||

| 12 months | GA | –c | 631 (396) | −151 | 168 (391) | 67 | 800 (680) | −83 (−467–251) |

| UC | 0 | 481 (877) | 236 (324) | 716 (1,096) |

aStandard deviation

bBootstrapped 95% confidence interval

cIncluded in total cost of physiotherapy interventions

At the end of the first follow-up year the gross mean cost difference based on GLPD and the net mean cost difference in terms of NLPD was in favor of the GA group, i.e., €3,655 (95% CI: 157; 6,933) and €999 (95% CI: −1,073; 3,115), respectively. This direction of the between-group difference was maintained in the second and third follow-up years as well, but it was not statistically significant. The costs of productivity loss were the main cost driver in this study with 87 and 90% of the total net costs in GA and UC group, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis

The recalculation with a 25 and 50% decrease in work performance in the first follow-up year, resulted in an increase in the mean difference in costs between the GA and UC from €999 to €1,663 and €2,327 in favor of the GA group for a 25 and 50% decrease in work performance, respectively. Comparable findings were observed for the second and third follow-up years.

In the first follow-up year an average investment in the GA intervention of €475 (SD 203) per worker yielded a savings of €999 (95% CI: −1,073; 3,115) due to a reduction in productivity loss. Over a 3-year period, the potential saving was calculated at an average of €1,661 (95% CI: −4,154; 6,913) per worker. When the first year difference in HCU costs between the groups is considered, an additional expenses to GA intervention of €83 (95% CI: −467; 251) resulted in the aforementioned savings on sick-leave benefits.

Discussion

Although the general direction of the cost–benefit findings in this study was robust and constantly in favor of the intervention group over all follow-up years and the GA group returned significantly faster back to work, the mean cost differences were not statistically significant. This is a common problem in trials which are underpowered for skewed data distribution such as costs of health utilization or productivity loss. The study was performed within a single company and the majority of the subjects were male, blue-collar workers. These factors should be taken in account when one will generalize the findings to other work situation.

We used sick-leave days as a proxy measure for productivity loss. However, it is not clear how accurately this proxy measure reflects true production losses. First of all, the actual level of production loss may be influenced by the type of compensation mechanisms that exist within a job title. For example, work normally performed by the absent employee may be completed by colleagues, or made up upon RTW during usual working hours. In such a situation, the absenteeism of the employee would not lead to productivity loss and therefore, should not be considered a cost. In this study, the majority of employees had service-related jobs, e.g., airplane maintenance technicians, pilots, baggage handlers, where the possibility of postponing production until later or “doing more with less” were not viable options. Furthermore, the way in which productivity loss costs are estimated can lead to quite different results. In our study, we estimated productivity loss costs in four different ways: gross, net and with an assumption of either 25 or 50% decreased work performance. The gross estimation is likely to be an overestimation as workers who return to their original duties on a part-time basis, or who perform alternative job tasks, conduct work in some format. On the other hand, the net cost estimation may be an underestimation as workers who are still not fully recovered may not be 100% productive. The sensitivity analysis in which a 25 or 50% decrease in work performance was assumed, albeit arbitrarily, takes this into consideration. This inaccuracy of lost productivity estimation could be partially solved by the use of recently developed questionnaires for measuring health-related work performance [12, 13].

There are only few published cost–benefit and/or cost–effectiveness evaluations of RTW interventions for sub-acute LBP. Loisel et al. demonstrated that an occupational intervention in combination with participatory ergonomics and multidisciplinary work rehabilitation were cost-beneficial and cost-effective at mean follow-up of 6.4 years [16]. Gatchel et al. showed that an early intervention program for workers who were at high risk for developing chronic LBP significantly reduced the number of work disability days and the total costs at 12-month follow-up [5]. Recent Finnish research by Karjalainen et al. disclosed a reduction in the total number of sick-leave days and total costs for workers who experienced hinder at their work due to sub-acute LBP and who participated in a mini-intervention when compared to UC [11]. The findings of our study that a RTW intervention for sub-acute LBP is cost-beneficial, although not statistically significant, in comparison to UC are in accordance with these studies.

The results suggest that GA is associated with a positive return on investment and this study provides a framework for further research. Such future research should not only concentrate on the evaluation of more trials, but also on further developing of methodology of economic evaluation for practical use by employers, occupational services and also by workers.

Conclusions

The GA intervention for non-specific LBP may be a cost-beneficial RTW intervention from the employer’s point of view. This intervention was marginally more expensive than UC, while benefits were substantial and remained noticeable 3 years after the initial intervention. The costs of health utilization were only a fraction of the total cost of the LBP in the working population and the economic burden of productivity loss was the main cost driver.

Acknowledgment

Grant support: by the Dutch Health Insurance Executive Council (CVZ), grant DPZ 169/0.

References

- 1.Courtney TK, Matz S, Webster BS. Disabling occupational injury in the US construction industry, 1996. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:1161–1168. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutch Central Organisation for Health Care Charge, Utrecht (1998) Tariffs for medical specialist, excluding psychiatrists. Supplement to tariffs decision number 5600-1900-1 from 10 December 1998 [in Dutch: Het tariefboek voor medisch specialist, exclusief psychiaters. De bijlage bij tariefbeschikking 5600-1900-1 d.d. 10 december 1998]

- 3.Elders LA, Burdorf A. Prevalence, incidence, and recurrence of low back pain in scaffolders during a 3-year follow-up study. Spine. 2004;29:101–106. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000115125.60331.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elders LA, Beek AJ, Burdorf A. Return to work after sickness absence due to back disorders—a systematic review on intervention strategies. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2000;73:339–348. doi: 10.1007/s004200000127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Noe C, Gardea M, Pulliam C, Thompson J. Treatment- and cost-effectiveness of early intervention for acute low-back pain patients: a one-year prospective study. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13:1–9. doi: 10.1023/A:1021823505774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goetzel RZ, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S. The health and productivity cost burden of the “top 10” physical and mental health conditions affecting six large U.S. employers in 1999. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:5–14. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagen EM, Eriksen HR, Ursin H. Does early intervention with a light mobilization program reduce long-term sick leave for low back pain? Spine. 2000;25:1973–1976. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagen EM, Grasdal A, Eriksen HR. Does early intervention with a light mobilization program reduce long-term sick leave for low back pain: a 3-year follow-up study. Spine. 2003;28:2309–2315. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000085817.33211.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Indahl A, Velund L, Reikeraas O. Good prognosis for low back pain when left untampered. A randomized clinical trial. Spine. 1995;20:473–477. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199502001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Indahl A, Haldorsen EH, Holm S, Reikeras O, Ursin H. Five-year follow-up study of a controlled clinical trial using light mobilization and an informative approach to low back pain. Spine. 1998;23:2625–2630. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Mutanen P, Roine R, Hurri H, Pohjolainen T. Mini-intervention for subacute low back pain: two-year follow-up and modifiers of effectiveness. Spine. 2004;29:1069–1076. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35:245–256. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koopmanschap MA. PRODISQ: a modular questionnaire on productivity and disease for economic evaluation studies. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2005;5(1):23–28. doi: 10.1586/14737167.5.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindstrom I, Ohlund C, Eek C, et al. The effect of graded activity on patients with subacute low back pain: a randomized prospective clinical study with an operant-conditioning behavioral approach. Phys Ther. 1992;72:279–290. doi: 10.1093/ptj/72.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loisel P, Abenhaim L, Durand P, et al. A population-based, randomized clinical trial on back pain management. Spine. 1997;22:2911–2918. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loisel P, Lemaire J, Poitras S, et al. Cost–benefit and cost–effectiveness analysis of a disability prevention model for back pain management: a six year follow up study. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:807–815. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.12.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maetzel A, Li L. The economic burden of low back pain: a review of studies published between 1996 and 2001. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16:23–30. doi: 10.1053/berh.2001.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maniadakis N, Gray A. The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain. 2000;84:95–103. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oostenbrink J, Koopmanschap M, van Rutten F (2000) Handbook for cost studies, methods and guidelines for economic evaluation in health care (in Dutch: Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek, methoden en richtlijnprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg). Health Care Insurance Council

- 20.Perez A, Dennis RJ, Gil JF, Rondon MA, Lopez A. Use of the mean, hot deck and multiple imputation techniques to predict outcome in intensive care unit patients in Colombia. Stat Med. 2002;21:3885–3896. doi: 10.1002/sim.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staal JB, Hlobil H, Twisk JW, Smid T, Koke AJ, Mechelen W. Graded activity for low back pain in occupational health care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:77–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-2-200401200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taxe report (2000) Z-index (in Dutch). The Hague

- 23.Williams DA, Feuerstein M, Durbin D, Pezzullo J. Health care and indemnity costs across the natural history of disability in occupational low back pain. Spine. 1998;23:2329–2336. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199811010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:646–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]