Abstract

BACKGROUND

African-American women are disproportionately affected by obesity. Weight loss can occur, but maintenance is rare. Little is known about weight loss maintenance in African-American women.

OBJECTIVES

(1) To increase understanding of weight loss maintenance in African-American women; (2) to use the elicitation procedure from the theory of planned behavior (TPB) to define the constructs of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control regarding weight loss and maintenance; and (3) to help develop a relevant questionnaire that can be used to explore weight loss and maintenance in a large sample of African Americans.

DESIGN

Seven focus groups were conducted with African-American women: four with women successful at weight loss maintenance, three with women who lost weight but regained it. Discussions centered on weight loss and maintenance experiences.

PARTICIPANTS

Thirty-seven African-American women.

APPROACH

Content analysis of focus group transcripts.

RESULTS

Weight loss maintainers lost 22% of body weight. They view positive support from others and active opposition to cultural norms as critical for maintenance. They struggle with weight regain, but have strategies in place to lose weight again. Some maintainers struggle with being perceived as sick or too thin at their new weight. Regainers and maintainers struggle with hairstyle management during exercise. The theoretical constructs from TPB were defined and supported by focus group content.

CONCLUSIONS

A weight loss questionnaire for African Americans should include questions regarding social support in weight maintenance, the importance of hair management during exercise, the influence of cultural norms on weight and food consumption, and concerns about being perceived as too thin or sick when weight is lost.

KEY WORDS: African Americans, weight loss maintenance, theory of planned behavior, focus group

African-American women are disproportionately affected by overweight and obesity,1,2 and have a higher incidence of many of the diseases for which obesity is a risk factor.3,4 Consequently, excess weight is a key contributor to disparities in health. Numerous studies have explored issues of weight loss and physical activity among African-American women. Despite estimates that 70% of African-American women want to lose weight and nearly 50% are actively trying to lose weight,5 African-American women lose less weight than other ethnic groups6 and engage in weight loss methods for shorter periods of time.7,8 Although some studies have shown modest weight loss when interventions are specifically tailored for African-American participants,9–11 more knowledge is necessary for the development of interventions that promote not only significant weight loss but also weight loss maintenance.

WEIGHT LOSS MAINTENANCE

In all populations, successful initial weight loss often does not result in sustained weight loss.12 Health benefits of weight loss are lost when the weight is regained.13,14 Among individuals successful with weight loss, few are able to maintain their new weight. Successful weight loss maintainers are a unique, important group from which useful information can be gathered. Their characteristics and strategies for weight loss maintenance can provide a basis for the development of successful weight loss and maintenance interventions.

Successful long-term weight maintenance is not well understood among African Americans, with only two studies that have examined weight loss maintenance. One assessed weight loss maintained at 32 weeks. Of 16 women who completed the 16-week acute weight loss program, 10 also completed the 16-week maintenance program and maintained a weight loss of 10.7 lbs. The women who completed the weight loss maintenance program demonstrated improved control regarding environmental hunger and eating cues compared to baseline.15 The second study included two focus groups, one of women who had lost at least 10 lbs and maintained the loss for 1 year and a second group who had initially lost 10 lbs but regained it. Themes gathered from the focus groups demonstrated that successful weight loss maintainers were motivated to lose weight by tight or poorly fitting clothes. They maintained their weight loss behaviors because they felt better, had more energy, and looked better in their clothes. They did not perceive foods as good or bad, but felt that almost all foods were acceptable within a balanced diet and an active lifestyle.16 Both studies were limited by few participants and small numbers of pounds lost. They do not fully explore social factors or facilitators and barriers to weight loss maintenance, nor do they include participants who achieved clinically significant weight loss.17

THEORY AND BEHAVIOR

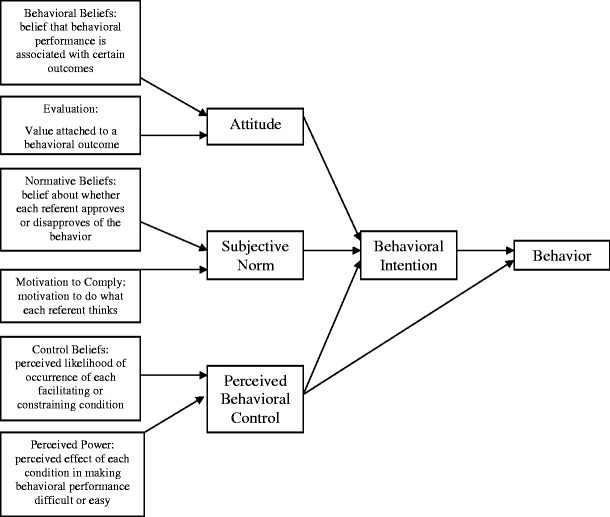

Participation in both dietary and physical activities to promote or maintain weight loss is a complex process and is influenced by a variety of factors. The theory of planned behavior (TPB)18 was developed to explain the many factors that contribute to the adoption of specific behaviors19: in this case, weight-loss-promoting behaviors. The TPB postulates that a complex web of beliefs, attitudes, norms, and motivations interact to influence behavior (Fig. 1). A fuller understanding of these factors could allow the development of focused interventions that may be successful at promoting desired behaviors. The theoretical constructs underlying TPB have been shown to be effective in predicting physical activity and healthy eating in various populations.20–27 The theory has been applied to behaviors within African-American groups.28,29 However, for physical activity and healthy eating, most studies focused on only one or two of its constructs and were not designed using the TPB in its entirety.

Figure 1.

Theory of planned behavior. Adapted from Glanz et al.19

African Americans have complex attitudes regarding weight loss. Most feel that weight loss and weight-promoting behaviors are beneficial to their physical health, mental health, and appearance and that these outcomes are positive.16,28,30 Other studies suggest that losing too much weight may be viewed as negative7 or that exercising too much may result in appearing too masculine.30 The role of subjective norms in African Americans is less clear. Studies suggest that the influence of subjective norm is not clearly predictive of intention to perform weight loss behaviors;29 however, it is possible that the collective African-American community and culture might have more social influence on an individual than one specific important other.28

Facilitators and barriers that constitute perceived behavioral control have been well studied in African-American women as it relates to control over adoption of weight loss activities.

BARRIERS

Among African-American women and factors that hinder weight loss have been described. Frequent ones include the high cost of healthy eating and participating in physical activity.15,31–33 Other barriers include lack of social support from family and friends,15,34 lack of time, lack of motivation, lack of role models,33 burden of family, and caregiving responsibilities,16,35 emotional stress,15 physical and health problems,30,33 as well as traditional foods and family eating expectations.32,36,37 African-American women describe lack of child care as a significant hurdle to engaging in physical activity.38,39 Two specific obstacles to exercise in their neighborhoods include concerns about inclement weather39,40 and safety15,33 Lastly, some studies demonstrate that overweight and obese African-American women are not satisfied with their bodies,32 whereas other studies suggest a higher level of body satisfaction at larger sizes among African-American women.41–43 This tolerance of heavier weights is often used to explain reduced desire for weight loss.

FACILITATORS

In general, the factors that would promote weight loss activities are the opposite of the barriers described by African-American women. Low-cost food and physical activity options might increase engagement in weight loss efforts.32 Support from family and friends, provision of childcare, and relief from family and caregiving responsibilities would allow time for physical activity.33 In addition, enjoyment of the type of physical activity performed could be motivating.30 Weight management programs that include a weight maintenance component and are designed to address emotional and psychological concerns through spiritual means, in addition to weight, would be preferred by African-American women.32

QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT

The TPB has been used as a framework for the development of questionnaires.21 The TBP is grounded in the perspectives of the target population and requires eliciting the circumstances and factors involved in a behavior from the specific population in question.19 Focus groups are a useful means for eliciting the views of the study population regarding a specific behavior and are effective for the development or improvement of questionnaires in populations that have not been widely studied.36,44

STUDY PURPOSE

African Americans who are successful long-term weight-loss maintainers are an important group from which strategies for weight loss and maintenance can be understood. This study will add to the limited literature a better understanding of weight loss maintenance among African-American women who have lost and maintained clinically meaningful amounts of weight.

The purpose of this focus group study is threefold: (1) to augment our understanding of successful weight loss maintenance in African-American women; (2) using the TPB, to explore the constructs of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control regarding weight loss and maintenance in African Americans; and (3) to help develop a reliable, relevant, and valid weight loss questionnaire that can be used to explore weight loss and weight loss maintenance in a larger sample of African Americans.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted seven focus groups from April 2004 to January 2005 to explore weight loss and maintenance experiences of African-American women. Each group was composed of African-American women from a large urban city in the southwestern United States. Three of the groups included women who had lost at least 10% of their body weight and regained the weight (regainers). Four of the groups included women who had lost at least 10% of their body weight and had maintained the weight loss for at least 1 year (maintainers). The amount and duration of weight loss was provided by self-report. Self-report of weight has been demonstrated to be acceptable in other studies.45,46 All weight loss maintainers provided proof of their weight loss maintenance with either a before and after picture or a signed statement from a physician or significant other.

Eight open-ended questions were developed by the principal investigator and a group of advisors based on previous literature regarding weight loss and weight loss maintenance.7,16,34,47–51 Development of the questions was guided by the TPB to identify salient beliefs and experiences regarding weight loss and maintenance among African Americans.18,19 The guide questions (Table 2) were purposefully broad to encourage open discussion not simply limited to the TPB constructs. In addition, questions were developed to elicit open discussion about general weight loss experiences, motivations for weight loss, and strategies for overcoming barriers to weight loss and maintenance. The discussions allowed the participants to share their experiences and beliefs regarding weight control in their own words. The focus groups were conducted at the main campus of a medical school or in the family and community medicine offices. Each session lasted approximately 90 minutes.

Table 2.

Focus Group Themes

| Question | Maintainers | Regainers |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tell me about your experiences with losing weight? | ||

| Major themes | Multiple weight loss attempts and multiple weight loss methods used | Multiple weight loss attempts and multiple weight loss methods used |

| Maintenance of a balance between food choice and physical activity is necessary | Short-term success achieved | |

| Weight loss has been important to avoid embarrassment | ||

| Minor themes | Do not engage in a diet, but a lifestyle change | |

| Difficult to resolve conflict between achieving a healthy weight and being perceived as too thin or sick | ||

| 2. What motivated you to lose weight? | ||

| Major themes | Prevention and management of health conditions | Prevention and management of health conditions |

| Avoidance of being physically unappealing to self and others | Desire to look good in clothes | |

| Influence of family and friends’ attitudes about weight | Desire to be physically attractive to others | |

| Minor theme | ||

| 3. What were the important reasons you were able to lose weight? | ||

| Major themes | Positive support from others | Desire to improve health |

| Influence of psychological and financial issues related to clothing | Desire to improve physical appearance | |

| Avoidance and management of health conditions | ||

| Minor theme | Influence of religious faith and prayer | |

| 4. What were the greatest challenges in losing weight? | ||

| Major themes | Lack of time for physical activity and healthy living | Influence of a food centered culture (ethnic, family, and general culture) |

| Expense of maintaining a healthy lifestyle | Lack of time because of other commitments | |

| Resisting temptation from environment and family | Impact of stressful life events | |

| Minor theme | Management of hairstyle during exercise | Management of hairstyle during exercise |

| 5. How did you overcome the challenges? | ||

| Major themes | Identify specific strategies for managing hair | Identify specific strategies for managing hair |

| Implement strategies to counteract cultural and family norms | Implement diet and physical activity strategies to promote weight loss | |

| Maintain cognitive vigilance to resist temptation | ||

| Minor theme | ||

| 6. How did you maintain the weight you loss? | ||

| Major themes | Engage in physical activity | |

| Make healthy food choices | ||

| Define personal strategies for maintenance of a healthy lifestyle | ||

| Minor themes | Receive positive support and encouragement from others | |

| Use clothes to cue when weight regain is occurring and weight loss needs to be reinitiated | ||

| 7. What things resulted in your regaining the weight you loss? | ||

| Major themes | Laziness | |

| Insurmountable time management challenges | ||

| Lack of willpower | ||

| Minor theme | ||

| 8. Why is it so difficult for people to lose weight and keep it off? | ||

| Major themes | Lack of willpower | Requires complete lifestyle change |

| Lack of supportive environment | Requires management of time and balance with family responsibilities | |

| Minor themes | ||

| 9. What advice would you give to someone who is trying to lose weight and to keep it off? | ||

| Major themes | Set realistic weight loss goals | Change lifestyle |

| Find a personal and genuine motivation to change and sustain a healthy lifestyle | Maintain a mental focus on weight control | |

| Implement specific diet and physical activity strategies | ||

Major themes include the concepts that were generated spontaneously by focus group participants and that appeared frequently throughout the discussion and were identified as salient themes by the transcript evaluators. The minor themes represent concepts that generated a good deal of discussion, but did not occur spontaneously among the participants; they occurred when probed by the moderator.

Participants

African-American adults, 18 years old or older, were recruited for participation. Both men and women were recruited for the study; however, there were very few men who expressed interest in participating in a focus group about weight. Therefore, this study included African-American women only.

Recruitment

Recruitment was generated through a variety of methods. Posters describing the project were placed in two county-based clinical care sites. The county health system largely serves low-income, ethnic minority residents of the city and its surrounding area. Radio advertisements were broadcast from a local radio station with a primarily African-American audience. A staff-wide email of the poster was sent to medical center employees describing the project. Word of mouth method was used (e.g., participants told their friends and relatives about the project). Participants received a $40 gift card for participation and completion of a focus group session. All participants provided informed consent in compliance with the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board requirements.

Data Collection

Focus group discussion using standard methods44,52 were used. The focus groups were moderated by trained researchers who were African-American women and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts and demographic information provided by participants were the data for our analyses.

Analysis

The focus group transcripts were evaluated by a multiethnic team of men and women. The evaluators read each of the transcripts independently and identified the themes that emerged in response to the focus group guide questions. The evaluators then attended two separate meetings to discuss the themes of the focus groups: one for the regainers and another for the maintainers. During the analysis meetings, each evaluator reported the major thematic responses he or she identified in the transcript related to each guide question. All of the themes identified for each question were written on a board and discussed by the group. There were no new themes that emerged after review of the second transcript from each category (maintainers and regainers) of focus group discussions. A consensus was reached by the evaluators on the most important themes for each question. The selection of themes was supported by the number of times a specific response arose in the transcripts and the amount of concurrence or disagreement with that response by the other focus group participants.

RESULTS

Sample

All participants completed all or part of a demographic questionnaire (Table 1). There were 23 weight regainers and 14 weight maintainers. The age of the participants in each group was similar. The maintainer group lost more weight on average than the regainer group, 59.5 versus 37.1 lbs, respectively. The average current BMI for both groups at the time of the study was ≥29.5.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Maintainers | Regainers | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 14 | 23 |

| Mean age | 40.4 | 43.7 |

| Employed | 12 (85%) | 18 (82%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 7 (50%) | 9 (39%) |

| Married | 2 (14%) | 9 (39%) |

| Widowed | 0 | 2 (9%) |

| Divorced | 5 (36%) | 3 (13%) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Less than high school | 0 | 0 |

| High school graduate | 0 | 5 (22%) |

| Some college | 4 (29%) | 11 (48%) |

| College graduate | 7 (50%) | 5 (22%) |

| Graduate school | 3 (21%) | 2 (8%) |

| Mean start weight | 234.3* | 191.1* |

| Mean weight loss | 59.5* | 37.1* |

| Mean percent weight loss | 22%* | 19%* |

| Mean current weight | 179.6 | 218.2 |

| Mean BMI | 29.5† | 36.0‡ |

*Data missing on one maintainer participant and one regainer participant.

†Only 4 of the 14 maintainers have a BMI of less than 25. Five are obese by BMI and one is morbidly obese with a BMI of 46.32. Without including her in the calculation of mean BMI, the mean is 28.20.

‡One regainer participant had a BMI within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines’ normal range of 18.5 to 24.9 (23.01).54

Qualitative Findings

The broad themes extracted from the focus groups are shown in Table 2. Maintainers used a variety of weight loss methods and frowned upon the concept of diets. They understood that a balance between the food they ate and the exercise they did was critical to weight loss. Their weight loss was tied to the avoidance of embarrassment and negative self-image. Many of the women described self-perception or other’s perception that their weight loss resulted in them being too thin or sickly. The maintainer group cited health concerns, physical attractiveness, looking good in clothes, and the attitude of their family and friends toward weight and weight loss as important motivators to their success. They also described avoidance of wearing larger sizes and paying for larger clothes as motivating. Lack of time for physical activity or healthy food preparation was described as a barrier to weight-loss-promoting behaviors. Resisting temptations and avoiding food-laden environments with family or coworkers was an obstacle to weight loss. Although management of hair did not emerge as a major challenge to weight loss, discussion of hairstyle management did emerge as a major theme when participants were asked how they overcame challenges related to weight loss. A variety of hairstyles and avoidance of exercise were offered as ways to address hairstyle concerns related to physical activity, sweat in particular. The women in the maintainer group described specific personal strategies they employed when they struggle with a challenge related to weight loss and they described open resistance to cultural and family norms regarding food quantity and type. For weight maintenance, the women described persistent vigilance regarding physical activity and food consumption; however, they admitted that they do regain weight at times. They identified tight fitting clothes as their cue to weight regain and had a specific personal strategies planned to reinitiate weight loss if that occurred.

The women in the regainer group also used a variety of weight loss methods for weight loss, many of which were fad diets or over the counter supplements. They too cited health concerns and physical attractiveness as key motivators for weight loss. In terms of barriers to weight loss, women who had regained their weight felt that finding a balance between time for physical activity or healthy food preparation and other commitments and care giving responsibilities was a huge hurdle to weight loss. They felt that family and work environments with abundant, high-calorie food made it difficult for them to lose weight. Like the maintainer group, the women who regained weight did not identify hair management as a major challenge to weight loss, but did spontaneously discuss hair management when asked how they overcome challenges. They too described different hairstyling options and exercise avoidance as their response to the challenge. The regainer group offered a list of activities that should be done to lose weight, but did not describe strategies for overcoming obstacles to engaging in those activities. When asked what things resulted in their regaining weight, they revealed that laziness, lack of motivation, and inability to manage time were the primary causes of weight regain.

DISCUSSION

Our study is one of the few that has attempted to understand weight loss maintenance in African-American women. Our qualitative findings have two major results: (1) we identified a number of important themes related to weight loss experiences among African-American women (Table 2), and (2) we found support for the theoretical constructs underlying the TPB, specifically regarding weight-loss-promoting behaviors in African-American women, which we have delineated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Theory of Planned Behavior: Construct Components

| Construct | Focus Group Findings | Questionnaire examples |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ||

| Outcomes are associated with weight loss and maintenance | Avoidance of embarrassment | Losing weight will help improve my blood pressure |

| Being perceived as too thin or sick | Unlikely..........................................Likely | |

| Avoidance of being physically unappealing | Improving my blood pressure is | |

| Management of health conditions | Bad................................................Good | |

| Subjective norm | ||

| Important referent others | Husband | My doctor thinks that I should keep off the weight I have lost |

| Boyfriend | Disagree..........................................Agree | |

| Men | I generally want to do what my doctor thinks I should do | |

| Family | Disagree..........................................Agree | |

| Friends | My friends think that I should keep off the weight I have lost | |

| Coworkers | Disagree..........................................Agree | |

| Children | I generally want to do what my friends think I should do | |

| Mother | Disagree..........................................Agree | |

| Father | ||

| Doctor | ||

| Perceived behavioral control | ||

| Facilitators and barriers to weight loss and maintenance | Positive support from others | When exercising, I have a hard time managing my hair |

| Religious faith | Disagree..........................................Agree | |

| Cost of clothing | Managing my hair makes participating in exercise | |

| Lack of time | Difficult..........................................Easy | |

| Cost of healthy foods | When trying to lose weight, I have a hard time controlling my eating when I am at a family function | |

| Cost of being physically active | Disagree..........................................Agree | |

| Management of hair during exercise | The struggle to control my eating at family functions makes losing weight | |

| Influence of food centered culture | Difficult..........................................Easy | |

| Temptation from food | ||

| Cultural norms | ||

| Laziness | ||

| Caregiving responsibilities | ||

| Impact of stress on weight loss | ||

COMMON THEMES

The themes identified in this focus group study of weight loss maintainers and weight loss regainers confirm much of the existing knowledge regarding the weight loss experiences of African Americans. Most factors that influence acute weight loss are also important in weight loss maintenance. Specifically, both successful and unsuccessful weight loss maintainers are motivated to lose weight by their health and appearance. They struggle with lack of time for weight-loss-promoting activities, cost of healthy eating and being physically active, temptations to eat high-calorie foods and large quantities of foods (at work and with family), hairstyle management during exercise, and willpower. Aside from hairstyle management, many of the themes identified are not unique to African Americans, but have been described in other populations as well.8,31,33,40 The identification of hairstyle management during exercise as an issue in African-American women has been previously reported;53 however, its degree of influence on exercise adherence is not understood. The women in this study offered a variety of hairstyle management solutions including adopting easy to manage styles (pony tails, braids, and afros), setting aside adequate time to style hair after exercise, and avoiding exercise if their hair had been recently styled. Many of the women, however, stated that they are still trying to find a way to maintain an attractive hairstyle and be physically active. Because physical activity is an important component of weight loss maintenance, the role of hairstyle management and exercise adherence in African-American women is an area of research worthy of focus.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN MAINTAINERS AND REGAINERS

There were important differences between weight loss maintainers and regainers. Women in the maintainer group hold a strong belief in the importance of positive support from other people. Although absent in the regainer group, social support has been described as important for acute weight loss in numerous other weight-related studies of African-American women.15,33,34 This study suggests that social support is a potent facilitator for long-term weight maintenance as well. Another difference between the groups is the approach to the barrier of family and cultural expectations to eat high-calorie foods or large quantities of food. The maintainer group proposed active opposition to those influences with some focus group members refusing to participate in family functions if healthy food options were not available. This demonstrates the skill to overcome a barrier that might compromise weight control. The last notable difference between the two groups was the difference in their responses to weight regain. Both groups used the cue of tight fitting clothing to identify their relapse. However, the weight loss maintainers described specific plans they used to manage weight regain: drink more water, eat out less and cook at home, and exercise more than usual. Having a planned strategy in advance was a consistent practice among maintainers and was distinctly different from weight regainers who could not overcome laziness and lack of willpower when they regained weight.

THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR

Our study confirms the general understanding of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in African-American women as it relates to weight loss and corroborates the theoretical constructs underlying TPB. The three major constructs underlying TPB include attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. For attitude, the study demonstrates that the women have both positive and negative beliefs regarding weight loss. They want to lose weight to improve their health, to avoid embarrassment, and to be physically appealing to themselves and others. Conversely, they worry that too much weight loss might cause them to be perceived as sick. For subjective norms, these women described a variety of referent others including friends, family, mother, father, children, coworker, doctor, husband, boyfriend, and men. Discussion content that reflected perceived behavioral control included a variety of facilitators and barriers to weight loss and maintenance that have been described in the literature: positive support from others, supportive role of faith, time constraints, laziness, stress/emotions, caregiver responsibilities, food-centered work and family culture, food temptations, and hairstyle management. Lastly, the behaviors of healthy eating and performance of physical activity were both clearly identified by the maintainer group as the behaviors employed for weight maintenance. These findings from the elicitation phase along with existing literature will shape the development of a questionnaire to be used among a large group of African Americans regarding their weight loss and weight maintenance experiences.

QUESTIONNAIRE CONTENT

The themes from this focus group study define a variety of areas that are important to African Americans regarding weight loss: the role of social support in weight loss maintenance, the influence of familial and cultural expectations regarding food consumption, the role of hairstyle management in physical activity, and the importance of establishing a relapse prevention plan when weight regain occurs. Furthermore, these themes define the constructs for the TPB as it relates to weight loss and maintenance in this group. Examples of questions to be used in the questionnaire using the TPB are listed in Table 3.

WEIGHT LOSS MAINTAINED

The weight loss maintainers in this study reduced their weight by more than 59 lbs (22% of their body weight), which surpasses the 10% that is considered an ideal goal for improvement of health.17 However, even with clinically successful weight loss maintenance, only 4 of the 14 maintainers had a current BMI in the normal range.54 These findings are consistent with previous studies that suggest ideal body weight and image among African Americans may be heavier than that for other racial/ethnic groups.55–60

LIMITATIONS

The results of this study may only be relevant for African-American women. Once developed, the questionnaire, which is intended for African-American men and women, will need to undergo revision based on feedback from men. In addition, because the study was conducted by a college of medicine, respondents may have overemphasized health concerns. Third, the participants in our focus group lost substantial amounts of weight, more than typically seen in studies of weight loss. Finally, our study sample was small with only 37 participants. Conversely, focus groups do not require large sample sizes and our subjects had attained clinically meaningful weight loss, often not seen in other studies.

FUTURE RESEARCH

Findings from this focus group study, existing literature on weight loss and maintenance, and the TPB will be used for item development and testing of a questionnaire that explores the full range of weight control factors that are important in explaining individual differences among African Americans who lose weight and keep it off and those who regain it. African-American adults who have successfully maintained their weight loss and those who have regained it will be invited to participate in a registry and will be asked to complete the survey developed from the current study: African-American Weight Control Registry.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant no. 5 K08 DK064898 (Dr. Barnes) from the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Reference

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1723–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289(1):76–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Paeratakul S, Lovejoy JC, Ryan DH, Bray GA. The relation of gender, race and socioeconomic status to obesity and obesity comorbidities in a sample of US adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(9):1205–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1233–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Mack KA, Anderson L, Galuska D, Zablotsky D, Holtzman D, Ahluwalia I. Health and sociodemographic factors associated with body weight and weight objectives for women: 2000 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2004;13(9):1019–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stevens VJ, Hebert PR, Whelton PK. Weight-loss experience of black and white participants in NHLBI-sponsored clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(6 suppl):1631S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Tyler DO, Allan JD, Alcozer FR. Weight loss methods used by African American and Euro-American women. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(5):413–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Nothwehr F. Attitudes and behaviors related to weight control in two diverse populations. Prev Med. 2004;39(4):674–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Karanja N, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, Kumanyika SK. Steps to soulful living (steps): a weight loss program for African-American women. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(3):363–71. [PubMed]

- 10.Martin PD, Rhode PC, Dutton GR, Redmann SM, Ryan DH, Brantley PJ. A primary care weight management intervention for low-income African-American women. Obesity. 2006;14(8):1412–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Ard JD, Rosati R, Oddone EZ. Culturally-sensitive weight loss program produces significant reduction in weight, blood pressure, and cholesterol in eight weeks. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92(11):515–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Elfhag K, Rossner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005;6(1):67–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1 suppl):5–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Stevens VJ, Obarzanek E, Cook NR, et al. Long-term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Walcott-McQuigg JA, Chen SP, Davis K, Stevenson E, Choi A, Wangsrikhun S. Weight loss and weight loss maintenance in African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):686–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Young DR, Gittelsohn J, Charleston J, Felix-Aaron K, Appel LJ. Motivations for exercise and weight loss among African-American women: focus group results and their contribution towards program development. Ethn Health. 2001;6(3–4):227–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. Obes Res. 1998;6(suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed]

- 18.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Org Behav Human Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

- 19.Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass; 1997 (Jossey-Bass health series).

- 20.Blue CL. The predictive capacity of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior in exercise research: an integrated literature review. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18(2):105–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11(2):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Michels TC, Kugler JP. Predicting exercise in older Americans: using the theory of planned behavior. Mil Med. 1998;163(8):524–9. [PubMed]

- 23.Gatch CL, Kendzierski D. Predicting exercise intentions: the theory of planned behavior. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1990;61(1):100–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Povey R, Conner M, Sparks P, James R, Shepherd R. The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating: examining additive and moderating effects of social influence variables. Psychol Health. 2000;14:199–1006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Conner M, Norman P, Bell R. The theory of planned behavior and healthy eating. Health Psychol. 2002;21(2):194–201. [PubMed]

- 26.Nguyen MN, Otis J, Potvin L. Determinants of intention to adopt a low-fat diet in men 30 to 60 years old: implications for heart health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10(3):201–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Backman DR. Psychosocial predictors of healthful dietary behavior in adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34(4):184–192. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Peters RM, Aroian KJ, Flack JM. African American culture and hypertension prevention. West J Nurs Res. 2006;28(7):831–54; discussion 855–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Blanchard CM, Rhodes RE, Nehl E, Fisher J, Sparling P, Courneya KS. Ethnicity and the theory of planned behavior in the exercise domain. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(6):579–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Wilcox S, Richter DL, Henderson KA, Greaney ML, Ainsworth BE. Perceptions of physical activity and personal barriers and enablers in African-American women. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(3):353–62. [PubMed]

- 31.Blixen CE, Singh A, Thacker H. Values and beliefs about obesity and weight reduction among African American and Caucasian women. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(3):290–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Davis EM, Clark JM, Carrese JA, Gary TL, Cooper LA. Racial and socioeconomic differences in the weight-loss experiences of obese women. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1539–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Eyler AA, Baker E, Cromer L, King AC, Brownson RC, Donatelle RJ. Physical activity and minority women: a qualitative study. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(5):640–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Wolfe WA. A review: maximizing social support—a neglected strategy for improving weight management with African-American women. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(2):212–8. [PubMed]

- 35.Eyler AA, Matson-Koffman D, Vest JR, et al. Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity in a diverse sample of women: The Women’s Cardiovascular Health Network Project—summary and discussion. Women Health. 2002;36(2):123–34. [PubMed]

- 36.Carter-Edwards L, Bynoe MJ, Svetkey LP. Knowledge of diet and blood pressure among African Americans: use of focus groups for questionnaire development. Ethn Dis. 1998;8(2):184–97. [PubMed]

- 37.Airhihenbuwa CO, Kumanyika S, Agurs TD, Lowe A, Saunders D, Morssink CB. Cultural aspects of African American eating patterns. Ethn Health. 1996;1(3):245–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Nies MA, Vollman M, Cook T. African American women’s experiences with physical activity in their daily lives. Public Health Nurs. 1999;16(1):23–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Sanderson B, Littleton M, Pulley L. Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity among rural, African American women. Women Health. 2002;36(2):75–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Henderson KA, Ainsworth BE. A synthesis of perceptions about physical activity among older African American and American Indian women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):313–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Wolfe WA. Obesity and the African-American woman: a cultural tolerance of fatness or other neglected factors. Ethn Dis. 2000;10(3):446–53. [PubMed]

- 42.Baturka N, Hornsby PP, Schorling JB. Clinical implications of body image among rural African-American women. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(4):235–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Caldwell MB, Brownell KD, Wilfley DE. Relationship of weight, body dissatisfaction, and self-esteem in African American and white female dieters. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22(2):127–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 2000.

- 45.Must A, Willett WC, Dietz WH. Remote recall of childhood height, weight, and body build by elderly subjects. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(1):56–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Perry GS, Byers TE, Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Williamson DF. The validity of self-reports of past body weights by U.S. adults. Epidemiology. 1995;6(1):61–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, Seagle HM, Hill JO. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):239–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1 suppl):222S–5S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Breitkopf CR, Berenson AB. Correlates of weight loss behaviors among low-income African-American, Caucasian, and Latina women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(2):231–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Martin PD, Dutton GR, Brantley PJ. Self-efficacy as a predictor of weight change in African-American women. Obes Res. 2004;12(4):646–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Walcott-McQuigg JA, Sullivan J, Dan A, Logan B. Psychosocial factors influencing weight control behavior of African American women. West J Nurs Res. 1995;17(5):502–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research, 2nd ed. Qualitative Research Methods Series 16. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1997.

- 53.Railey MT. Parameters of obesity in African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92(10):481–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and Obesity: Home. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/obesity/. Accessed June 10, 2006; 2006.

- 55.Collins ME. Body figure perceptions and preferences among preadolescent children. Int J Eat Disord. 1991;10:199–208.

- 56.Harris SM. Racial differences in predictors of college women’s body image attitudes. Women Health. 1994;21(4):89–104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Lawrence CM, Thelen MH. Body image, dieting, and self-concept: their relation in African-American and Caucasian children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1995;24(1):41–48.

- 58.Mayville S, Katz RC, Gipson MT, Cabral K. Assessing the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in an ethnically diverse group of adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 1999;8(3):357–62.

- 59.Yates A, Edman J, Aruguete M. Ethnic differences in BMI and body/self-dissatisfaction among Whites, Asian subgroups, Pacific Islanders, and African-Americans. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(4):300–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Liburd LC, Anderson LA, Edgar T, Jack L, Jr. Body size and body shape: perceptions of black women with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 1999;25(3):382–8. [DOI] [PubMed]