We all live in an obesogenic environment.1 The availability of high energy dense, palatable, inexpensive food is only surpassed by the mechanized labor-saving and entertainment devices designed to keep us from moving too much. We have evolved from a society of hunter–gatherers to a society of drive-through picker-uppers. A number of factors likely determine our responses to the obesogenic environment, including level of exposure, resources available, and our biologic predisposition to energy imbalance. Despite the individual variation in these factors, certain patterns of obesity prevalence have developed over time, with a higher prevalence being noted in African American women. Reasons for a seemingly higher susceptibility of African American women to the obesogenic environment are unclear; equally unclear are the reasons for their differential response to treatment.

Papers in this issue of the Journal of General Internal Medicine by Lynch et al. and Barnes et al. identify factors that influence African American women and their interaction with the obesogenic environment.2,3 The perspective provided by each group, from examining attitudes about bariatric Surgery to struggles related to weight maintenance, is a unique contribution to the literature. Lynch et al. identified themes of lack of time and access to resources, issues regarding control, and identification with a larger body size. Women also expressed fears and concerns about the effects of bariatric Surgery and held perceptions that surgical treatment for obesity was an extreme measure.2 Barnes et al. reported that a key difference between African American women who maintain a significant weight loss and those who regain weight may be their individual ability to counter the environment of home, family, and friends that appears to be additive to the obesogenic environment.3

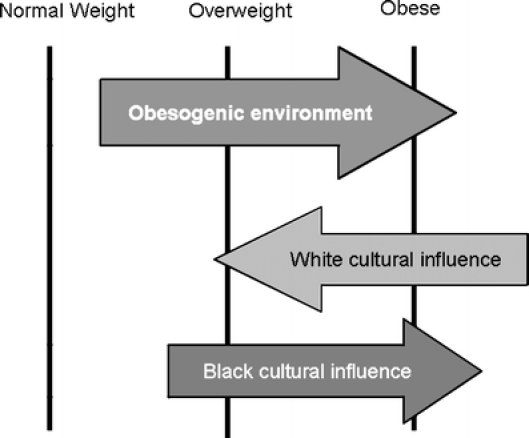

Are these barriers unique to African Americans or is it the response to these barriers that is unique? For example, most people might agree that lack of insurance coverage is a barrier to weight management because health insurance usually will not pay for weight control services. This barrier seems to be less specific to African American women and, at some level, could be considered a part of the overall obesogenic environment. It is important however, to consider the sociocultural context through which this barrier may be perceived by African American women. Some of our recent work suggests that African American and white women have distinctly different perceptions of how they should deal with their weight based to a significant degree on their racial identity.4 African American women routinely suggested that their cultural environment was permissive for, and in many instances even promoted, weight gain (Fig. 1). Conversely, white women suggested that they consistently receive prompts to be thin because thinness is highly valued by members of their racial group. The sociocultural context is important to consider because it provides the lens through which the barrier is perceived by the individual and influences the response to that barrier. Therefore, the lack of insurance coverage for weight control services is perceived in the context of limited personal resources to dedicate to weight loss and a general sense that other members of the African American community do not necessarily value thinness. Balanced against other financial responsibilities and a low perceived value for the investment, losing weight using one’s personal resources becomes low on the priority list. Therefore, it is likely that the barrier is uniquely perceived, and the response to that barrier is partially a function of that unique perspective.

Figure 1.

Confluence of obesogenic environment and cultural influence. Black cultural influence has an additive interaction with the overall obesogenic environment, further promoting obesity among black women. Conversely, white cultural influence acts as a counterweight to the prevailing obesogenic environment by influencing white women to strive for thinness.

Appreciation of the unique perspective of African American women is a key concept shared between the articles in this edition of the Journal of General Internal Medicine. While achieving a lower body weight may be important at an individual level for a given African American woman, many of the cultural norms African American women identify with suggest that being “skinny” is not truly critical to one’s happiness, health, and personal sense of well being. As a result, the energy required to overcome the initial inertia associated with challenging the obesogenic environment is significantly increased. At this point, the increased effort required to make or sustain the behavior change appears daunting, while conversely, a response that is similar to that of other members of the group would result in a sense of belonging and identity. This sense of group identity is particularly important because being a member of an ethnic minority group limits the opportunities for identifying with a wider array of groups, particularly outside of the racial boundaries. Going against the perceived cultural norms within the ethnic minority group can make one even more of a “minority.”

A primary example is that of ideal body image. African American women desire a smaller body image than their current body image. However, cultural norms suggest that African American women should have a different ideal of beauty and that ideal can be inclusive of a larger body size. When this is combined with a social context that increases exposure to fast food restaurants, lower wages, and limited access to places that are perceived to be safe for physical activity, it creates a level of inertia that is hard to overcome simply by one’s internal motivation. As noted in the paper by Lynch et al., “medical decision-making can be driven by one’s attitudes, beliefs, values, and opinions,”2 which are often informed by a collective social, environmental, and historical context. In the case of African Americans, the result is a shared cultural perspective and experience embraced by those who identify strongly with the group, perhaps at the exclusion of other perspectives. The key question is determining how to maintain that sense of identity, which has numerous positive benefits, while promoting an alternative response to the environment that appears to be associated with a different cultural perspective and identity.

One reason we lag behind in promoting alternative responses to the environment is that we lack sufficient data on the weight-related behaviors of African American women. We do not understand the extent to which a number of maladaptive eating behaviors exist in the African American community. Emotional eating, night eating syndrome, and binge eating are just a few examples alluded to by participants of the Lynch focus group study.2 We also do not have any specific, cohesive conceptual models regarding the behaviors of those who have been successful at weight loss and prevention of weight gain despite the sociocultural context. Current data sets such as the National Weight Control Registry (NWCR) have few minority participants, which reduces their generalizability.5 Studies and perspectives such as the paper by Barnes et al. provide a number of potential testable hypotheses based on the success of those who may have unique insight into the best strategies to promote behavior change in African American women. For example, it would be of interest to know if weighing on a regular basis (e.g., daily or weekly) is an applicable strategy as suggested by the NWCR, or if monitoring for “tight fitting clothes as their cue to weight regain” is more likely to keep African American women engaged in monitoring their weight.

Culturally targeted intervention programs have been the default answer to the conundrum of promoting weight loss in African American women; however, the evidence that they are more effective than standard behavioral treatments is lacking. Many of the barriers identified are not easily overcome at the individual level; an effective solution will require creative thinking, alternative ideas, and new models of intervention to address perceived barriers within the obesogenic environment. However, an effective solution will also involve reconciling the belief that many of the factors that are important to weight control are external, when the fact remains that creating a negative energy balance and engaging in healthful lifestyle behaviors is within the control of the individual. The participants who were successful in maintaining weight loss in the study by Barnes et al. had to individually oppose the influence of family members and others in their social circles to avoid what they perceived as detrimental behaviors or environments.3 In general, our current behavioral therapies do not routinely consider that there will be active opposition to behavior changes from members of the support system, leaving African American women less than prepared to generate support elsewhere. Without a change in this perspective, we will continue to provide less than adequate support for African American women attempting to alter their lifestyles.

These studies are important steps in the process to identifying effective solutions for helping African American women achieve healthy weights. The qualitative exploration of key perspectives from African American women appropriately satisfies some of the research priorities delineated by the African American Collaborative Obesity Research Network.6 However, this process is still in its initial stages. There is a need for a more rigorous definition of the components that make up culturally tailored programs. Testing of the effectiveness of these programs and their components has to be held to the same standards as other behavioral intervention trials. Furthermore, we can not ignore basic physiological differences that dictate the need for tailored dietary and physical activity prescriptions. Once the efficacy of tailored interventions is established, they need to be packaged in a health message that is salient for the target audience. Clearly defined, effective, and salient treatment plans will be the African American woman’s best hope for overcoming the inertia of the obesogenic environment.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Jamy Ard is supported by grants from NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK068223) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (51894).

References

- 1.Swinburn B, Egger G. The runaway weight gain train: too many accelerators, not enough brakes. BMJ. 2004;329(7468):736–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Lynch C, Chang J, Ford A, Ibrahim S. Obese African American women’s perspective on weight loss and bariatic surgery. J Gen Intern Med. 2007; DOI:dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606.007-0218-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Barnes A, Goodrick GK, Pavlik V, et al. Weight loss maintenance in African-American women: focus group results and questionnaire development. J Gen Intern Med. 2007; DOI:dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0195-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Malpede CZ, Greene LE, Fitzpatrick SL, et al. Racial influences associated with weight-related beliefs in African American and Caucasian women. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(1):1–5. [PubMed]

- 5.Phelan S, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, Wing RR. Are the eating and exercise habits of successful weight losers changing? Obesity. 2006;14(4):710–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kumanyika SK, Gary TL, Lancaster KJ, et al. Achieving healthy weight in African-American communities: research perspectives and priorities. Obes Res. 2005;13(12):2037–47. [DOI] [PubMed]