Abstract

Background

Residents have a major role in teaching students, yet little has been written about the effects of resident work hour restrictions on medical student education.

Objective

Our objective was to determine the effects of resident work hour restrictions on medical student education.

Design

We compared student responses pre work hour restrictions with those completed post work hour restrictions.

Participants

Students on required Internal Medicine, Surgery, and Pediatric clerkships at the University of Minnesota.

Measurements

Two thousand eight hundred twenty-five student responses on end-of-clerkship surveys.

Results

Students reported 1.6 more hours per week of teaching by residents (95%CI 0.8–2.6) in the post work hours era. Students’ ratings of the overall quality of their teaching on the ward did not change appreciably, 0.05 points’ decline on a 5-point scale (P = .05). Like the residents, students worked fewer hours per week (avg. 1.5 hours less, 95%CI 0.4–2.6). There was no change in quality or quantity of attending teaching, students’ relationships with their patients, or the overall value of the clerkships.

Conclusions

Whereas resident duty hour restrictions at our institution have had minimal effect on students’ ratings of the overall teaching quality, they do report being taught more by their residents. This may be a factor of decreased resident fatigue or an increased sense of well-being; but more study is needed to clarify the causes of our observations.

KEY WORDS: work hours, medical students, residents, medical education

INTRODUCTION

As of July 1, 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) placed restrictions on all resident duty hours. The major driving forces behind this change were improved patient safety and resident education and well-being.2 The Council postulated that a well-rested resident would be less likely to make mistakes, more receptive to learning, and better able to pursue outside interests.3–5

Limiting resident work hours without decreasing their responsibilities has the potential to force residents to choose between teaching/learning activities and completing other required tasks that may be perceived as more urgent. As Boex and Leahy6 point out, in their meta-analysis of multiple resident time motion studies, “residents are in a position of providing joint products simultaneously in that they must simultaneously learn, provide patient care and serve as teachers of students.” This pre work hour restrictions study found residents spending 36% of their time providing patient care, 35% in service related activities of marginal or no educational value, 15% in learning and teaching activities, and 16% in other activities. Proportionately decreasing all activities post work hour restrictions would lead to at least a small decrease in time spent teaching students. This decrease in time spent teaching might be greater if, as prior studies7 suggest, residents are more likely to sacrifice activities related to teaching and learning in favor of those directly related to patient care.

Alternatively, as the ACGME suggests, better-rested residents may be more receptive to their role as learners and teachers and, therefore, choose to teach more. This idea is supported by studies suggesting that Internal Medicine residents’ overall “well-being” is improved post duty hour restrictions7 and by student surveys indicating that residents’ post work hour restrictions appear to be more interested in and available for teaching.8 Our research further delineates the effects of residency work hour restrictions on medical student education by comparing students’ assessments of their experience on 4 required clerkships pre and post work hour restrictions. We primarily focus on assessments of the quality and quantity resident teaching. We hypothesized that decreased resident work hours would result in a decrease in the amount of time residents spent teaching and would negatively impact the students’ overall experience.

METHODS

End-of-Rotation Surveys

Students are required to complete end-of-rotation surveys for each of their required clerkships. We use an online electronic evaluation system—E*Value, which is part of Advanced Informatics’ medical management system. The surveys are used by the medical school to evaluate and improve clerkships. Hours worked and hours taught data are self-reported by the students. Likert scale ratings from 1 (poor) to 5 (outstanding) are used for the remaining survey questions. At a later date, it was determined that these data could be used to determine the effects of resident duty hour restrictions on student education by comparing the results of surveys completed by students before July 1, 2003 with those completed at a later date. It was our hypothesis that students’ responses on the clerkship surveys would reflect that the work hour restrictions had resulted in less teaching of medical students and an overall less satisfactory experience for the students. Use of these data for our study purposes was approved as Institutional Review Board exempt.

Participants

Two thousand eight hundred seventy-four end-of-clerkship surveys were assigned to University of Minnesota Medical School students rotating through 4 required clinical clerkships [Pediatric Clerkship (PEDS), Internal Medicine Clerkship (MED I), Internal Medicine Sub-internship (MED II), and Surgery Clerkship (SURG)] between July 1, 2001 and February 1, 2005. SURG surveys spanned October 1, 2001 to February 1, 2005, as they started using the electronic surveys slightly later. Each of the clerkships is 6 weeks in duration and averages every fourth night call. With the exception of MED I, during which students leave at 10 pm, call is in-house. During these clerkships, students rotate through a network of affiliated hospitals throughout Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Duluth and interact with residents from 6 separate residency programs.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome measures were student responses to the 2 following survey questions: teaching quality (What was the quality of your teaching overall: by attending physicians, residents, fellows, other staff?) and hours taught by residents (What was the amount of direct student teaching, wherein you were being taught directly and specifically by residents(s)/fellow(s)–approximate #hrs/week?). Secondary outcome measures included hours taught by attendings (What was the amount of direct student teaching, wherein you were being taught directly and specifically by attending physician(s)—approximate #hrs/week?), hours worked by students (List the average number of hours on duty/week in the hospital and/or clinic, including night call—approximate #hrs/week?), overall value (What was the overall educational value of course: consider course organization, teaching/learning environment and opportunities, evaluation and feedback?), quality of evaluation and feedback (quality of evaluation and feedback, overall), and relationship with patients (communication and relationships with patients).

Statistical Methods

The Jonckheere–Terpstra test was used to compare the pre and post work hour Likert responses, whereas data on hours worked and taught were analyzed with the Wilcoxon rank sum test and a bootstrap test of the difference of means, which were in agreement except in one instance. Confidence intervals were calculated with the BCa bootstrap method.9 Our analysis of the Likert-scaled questions excluded “not applicable” responses. The primary comparisons performed were pre versus post July 1, 2003. Students’ survey results may appear in more than 1 of the groups because they may have completed each of the 4 clerkships during the time the data were being collected. No students appeared in both the pre and post work hour restrictions analysis for a single clerkship (they were not compared against themselves for analysis). An additional comparison was made using the same tests of the subset July 1, 2001–July 1, 2002 versus December 1, 2003–December 1, 2004 to allow for a washout period around the time of institution of the work hour restrictions.

RESULTS

Survey Demographics

Of the 2,874 end-of-clerkship surveys assigned from July 1, 2001 to February 1, 2005, 2,825 were completed (98.3%). One hundred forty-four surveys were excluded for students who did not work with residents. The remaining 2,681 surveys were divided into groups of pre July 1, 2003 (1,342) and post July 1, 2003 (1,339).

Quantitative Analysis

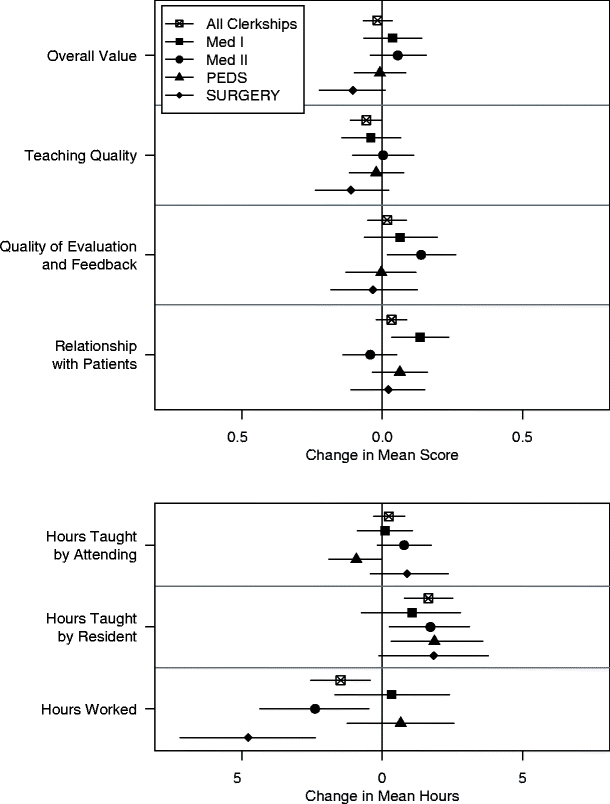

The students on the 4 designated clerkships reported that residents spent 1.6 more hours per week (P < .0001) teaching after the resident work hour restrictions were instituted. Individual analysis of the clerkships revealed that, for MED II, there was a statistically significant increase (P = .02) in hours taught by residents from 9.6 to 11.4 hours per week. For PEDS, there was also an increase from 10.4 to 12.3 hours spent teaching per week (P = .02). For MED I and SURG, individually, there was a trend toward residents spending more time teaching, but this was not statistically significant (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Hours Worked and Taught Pre and Post Work Hour Restrictions

| Question | Mean hours per week pre 7.03 | Mean hours perweek post 7.03 | Mean difference (hours) | 95% Bootstrap confidence interval | Bootstrap P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours taught by residents | |||||

| Combined | 10.23 | 11.87 | 1.64 | (0.80, 2.52) | <0.0001 |

| MED I | 11.15 | 12.21 | 1.06 | (−0.74, 2.83) | 0.24 |

| MED II | 9.6 | 11.4 | 1.7 | (0.29, 3.18) | 0.02 |

| PEDS | 10.4 | 12.3 | 1.9 | (0.28, 3.53) | 0.02* |

| SURG | 9.8 | 11.63 | 1.84 | (−0.12, 3.78) | 0.07 |

| Hours taught by attending | |||||

| Combined | 7.73 | 7.97 | 0.24 | (−0.30, 0.80) | 0.40 |

| MED I | 8.5 | 8.6 | 0.1 | (−0.90, 1.12) | 0.84 |

| MED II | 7 | 7.8 | 0.8 | (−0.14, 1.78) | 0.10 |

| PEDS | 8.2 | 7.3 | −0.9 | (−1.91, −0.06) | 0.04 |

| SURG | 7.28 | 8.17 | 0.89 | (−0.42, 2.35) | 0.21 |

| Hours worked | |||||

| Combined | 68.2 | 66.76 | −1.48 | (−2.55, −0.43) | 0.01 |

| MED I | 61 | 61.3 | 0.3 | (−1.72, 2.34) | 0.76 |

| MED II | 68.6 | 66.2 | −2.4 | (−4.35, −0.55) | 0.01 |

| PEDS | 69.8 | 70.4 | 0.6 | (−1.26, 2.55) | 0.49 |

| SURG | 73.32 | 68.55 | −4.78 | (−7.20, −2.38) | <0.0001 |

*BCa bootstrap method P value = .02, Wilcoxon P value = .09

Figure 1.

Mean difference pre to post work hours with 95% confidence intervals.

In aggregate, students on the 4 clerkships noted no change in the hours they were taught by their attending physicians pre to post work hour restrictions. However, on PEDS, students reported a decrease of 0.9 (8.2 to 7.3) hours per week in teaching by attending physicians (P = .04). A similar decrease was not noted on any of the other clerkships, and in fact, the trend for the other clerkships was toward an increase in the time attending physicians spent teaching.

On average, students worked 1.5 hours less per week post resident work hour restrictions (P = .01). For individual clerkships, the largest change post work hour restrictions was on Surgery where students reported working 4.8 hours less per week (P < .0001). Students on MED II worked 2.4 hours less per week (P = .01), whereas students on MED I and PEDS reported no change in hours worked after the resident work hour restrictions.

Qualitative Analysis (Fig. 1)

When clerkships were analyzed individually, no statistically significant changes in teaching quality were found. The aggregate analysis showed a numeric decline from 4.26 to 4.21 (P = .045) after resident work hours were restricted; however, this change is not likely “clinically significant.” There was no change in the students’ rating of overall value of these clerkships after the institution of the ACGME work hours restrictions. Whereas for MED II, there was a statistically significant increase in student evaluation of the quality of evaluation and feedback from 3.73 to 3.89 (P = .025), this effect was not seen in the combined data or on any of the other individual clerkship evaluations. Students on MED I rated their relationship with patients higher post work hours restriction (4.35 vs 4.53; P = .02), but this change was not seen in the combined analysis or on any of the other individual clerkships.

Other Analysis

We acknowledge that the work hour restrictions did not simply go into effect July 1, 2003 but, instead, were piloted and modified in the months before and after the deadline. We were concerned that the data obtained during this transition period (the 6 months before and after July 1, 2003) might bias the results because of contamination. To address this concern, we separately analyzed the data excluding this time period (comparing the July 1, 2001–July 1, 2002 data set with the December 1, 2003–December 1, 2004 data set). The findings of this subset were identical for our outcome measures.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates that the institution of the ACGME residency work hour restrictions did not adversely affect the amount of time that residents spend teaching medical students. In fact, we found a 1.6 hours per week increase in resident teaching time. We are not able to answer the question, “Why, in the face of increased time constraints, are residents choosing to spend more time teaching”? One theory is that residents are teaching more because of a decrease in fatigue and burnout. Although we did not specifically measure these factors in our residents, a number of studies have now demonstrated lower levels of burnout post work hour restrictions in Internal Medicine.7,10 It is not as clear that work hour restrictions have resulted in decreased burnout and fatigue for Surgery residents.11

In addition, we are unable to answer the question, “If residents are in the hospital less and teaching more, what is it that they are no longer doing”? Prior studies have found that resident conference attendance post work hour restrictions dropped significantly.10,11 Work hour restrictions have not been associated with decreased time spent in the operating room, clinic, or on rounds for Surgery residents.11 The authors hope the decrease in time has come from a decrease in the residents’ “service-related activities of marginal or no educational value,” but at least 1 study contradicts this notion.12

The increased time that residents spent teaching did not result in an increase in the students’ rating of the teaching on their clerkships. This question measured the overall teaching quality on the rotation and, therefore, is not specific to resident teaching; therefore, it is possible that work hour restrictions have resulted in increased resident teaching while other forms of teaching have declined in quality or quantity.

Prior studies suggest that post work hour restrictions, attending physicians are less available to students on Obstetrics–Gynecology and Surgery clerkships but either equally or more available to students on Internal Medicine and Pediatrics.13 Overall, our students report being taught the same number of hours per week by their attending physicians post resident work hour restrictions. For most clerkships, there is a trend toward increased attending teaching after restricting resident work hours. The exception to this is Pediatrics where attending teaching declined by 0.9 hours per week.

White et al.13 also found a general decline in the quality of student experience on procedurally oriented clerkships. In our study, there was a trend toward a decline in overall value and teaching quality on Surgery; however, this did not reach statistical significance. Previously, these declines have been attributed to Surgery residents spending proportionately more time in the operating room, but this does not correlate with our finding of increased resident teaching post work hours restriction.

Other important observations include that, on average, students worked 1.5 hours less per week post work hour restrictions. This decrease was most pronounced for the Surgery clerkship. In addition, our study supports the finding of previous papers that the majority of student education is performed by residents14 11.9 hours per week for residents versus 7.9 hours per week for attending physicians. This highlights the importance of exploring the effects of resident work hour restrictions, and any future changes in resident training, on medical student education. It is essential to medical student training that we support residents in their role as teachers.

Many aspects of the clerkship experience remain unchanged. Work hour restrictions did not significantly affect the quality of evaluation and feedback or students’ relationships with their patients. Most importantly, students rate the overall value of their clerkship experiences as unchanged pre to post work hour restrictions.

Limitations of our study include recall bias. Since the time data are self reported, the actual hours worked and taught could vary from those reported here. In addition, it is possible that students working fewer hours are happier and better rested, leading to a perception of being taught more by residents. One might expect, however, that this might lead to a global increase in ratings, which we did not find. Given our study design, other confounding factors (i.e., change in resident quality or greater emphasis on teaching) may have resulted in the increased time spent teaching. The authors (1 of whom is a program director) are not aware of any substantive changes in the residency programs, and we think this is an unlikely explanation, given the number of sites and residency programs with which our students interacted. Finally, it should be noted that our study is limited to students from 1 medical school interacting with residents from 6 residency programs representing 4 specialties in a limited geographic area. It remains to be seen if these findings would be replicated at other institutions.

Miller et al.15 showed that the medical student opinion regarding work hour limitations mirrors that of the ACGME. The top 3 reasons students favored the restrictions were the positive changes it would have on resident lifestyle, patient safety, and resident learning.14 We add the speculation, regarding beneficial outcomes, that better-rested residents may also be more receptive to their roles as teachers. Future research should be directed at how resident time has been reapportioned in an effort to explain our observations.

Acknowledgements

There was no research funding or support for this project.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure None disclosed.

Footnotes

Part of this research was presented at the Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine national meeting, fall of 2005. An abstract from that meeting was published in Teaching and Learning in Medicine under the title “ACE (Alliance for Clinical Education) Abstracts: Abstracts from the Proceedings of the 2005 Annual Meeting of the Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine (CDIM)” by Nixon et al. (Teach Learn Med 18(2):174,1).

References

- 1.Nixon LJ, Benson BJ, Rogers TB, Sick BT, Miller WJ. Effects of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work-hour restrictions on medical student experience. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18(2):174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Steinbrook R. The debate over residents’ work hours. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1296–302. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Charap M. Reducing resident work hours: unproven assumptions and unforeseen outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(10):814–5. [PubMed]

- 4.Skeff KM, Ezeji-Okoye S, Pompei P, Rockson S. Benefits of resident work hours regulation. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(10):816–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.American College of Graduate Medical Education. Resident duty hours and the working environment. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_Lang703.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2005.

- 6.Boex JR, Leahy PJ. Understanding residents’ work: moving beyond counting hours to assessing educational value. Acad Med. 2003;78(9):939–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Goitein L, Shanafelt TD, Wipf JE, Slatore CG, Back AL. The effects of work-hour limitations on resident well-being, patient care, and education in an Internal Medicine residency program. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2601–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Jagsi R, Surender R. Regulation of junior doctors’ work hours: an analysis of British and American doctors’ experiences and attitudes. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2181–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993:57.

- 10.Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, Prochazka AV. Burnout and Internal Medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2595–600. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gelfand DV, Podnos YD, Carmichael JC, Saltzman DJ, Wilson SE, Williams RA. Effect of the 80-hour workweek on resident burnout. Arch Surg. 2004;139(9):933–8; discussion 938–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Vidyarthi AR, Katz PP, Wall SD, Wachter RM, Auerbach AD. Impact of reduced duty hours on residents’ educational satisfaction at the University of California, San Francisco. Acad Med. 2006;81(1):76–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.White CB, Haftel HM, Purkiss JA, Schigelone AS, Hammoud MM. Multidimensional effects of the 80-hour work week at the University of Michigan Medical School. Acad Med. 2006;81(1):57–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Bing-You RG, Tooker J. Teaching skills improvement programmes in US Internal Medicine residencies. Med Educ. 1993;27(3):259–65 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Miller G, Bamboat ZM, Allen F, et al. Impact of mandatory resident work hour limitations on medical students’ interest in Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(4):615–9. [DOI] [PubMed]