Abstract

Medical educators have promoted skillful communication as a means for doctors to develop positive relationships with their patients. In practice, communication tends to be defined primarily as what doctors say, with less attention to how, when, and to whom they say it. These latter elements of communication, which often carry the emotional content of the discourse, are usually referred to as interpersonal skills. Although recognized as important by some educators, interpersonal skills have received much less attention than task-oriented, verbal aspects. Moreover, the field lacks a common language and conceptualization for discussing them. This paper offers a framework for describing interpersonal skills and understanding their relationship to verbal communication and describes an interpersonal skill-set comprised of Understanding, Empathy, and Relational Versatility.

Key words: interpersonal skill, teaching communication skills, doctor–patient relationship

Medical educators continue to affirm the connection between healing and human relationships.1,2 The literature to date has focused on how physicians build relationships with their patients using communication skills: specific, observable physician behaviors that are primarily verbal in form and have been shown to be associated with positive patient relationships and health outcomes.3,4 However, there is accumulating concern that focusing only on the physician is too narrow a view.5–8 Roter has observed that we examine doctor–patient communication “largely as a physician monologue”.9 This view neglects the reciprocal nature of discourse and the importance of a physician’s ability to interpret patient cues and adapt communication to individual patients. It also overlooks the personhood of the doctor, the fact that her characteristics and internal experience impact the interaction and its outcome.

Many educators recognize the less tangible aspects of communication such as timing and tone10–13 and refer to them as interpersonal skills (IS). The Kalamazoo II report on the assessment of physician communication states that, “Communication Skills and Interpersonal Skills are two distinct aspects of the same competence”.14 And yet the absence of a more specific description of IS in that report suggests that the field has yet to identify a common language and framework for the range of physician capacities that promote sensitive, effective, and mutually satisfying relationships with patients. This paper offers some thoughts about how we might define IS, understand their relationship to verbal communication skills, and what some of the relevant educational and assessment issues are.

Communication, according to the Mirriam-Webster dictionary, is the exchange of information.15 The instrumental tasks of health care are transacted in the doctor–patient relationship through the verbal channel of communication. Each participant relies on the specificity and precision of a shared abstract language to identify relevant concerns, construct an historical context, and plan an approach to care. However, beyond the words that convey this information, there are other dimensions of relationship being exchanged in the medical encounter: How do the participants feel about one another? Who assumes leadership? How might they discover an emotional mutuality to support the challenge of agreeing on a treatment approach? Communication about these interpersonal matters tends to be less verbal and deliberate than task-oriented communication.16

Nonverbal communication includes extratextual elements of a face-to-face exchange such as posture, facial expression, and dress, and it can support, modify, or even contradict verbal messages.17 Although nonverbal communication has been studied extensively, it resists reduction to a logical syntax like that employed in spoken words and writing. It uses a vocabulary that, like the Chinese character, is built of iconic rather than abstract symbols, and it is paradox-rich and context-sensitive.18,19 Eye contact, for instance, can reflect attentiveness, seduction or a challenge for dominance, depending on the participants and the situation.18 Despite this complexity, using tacit pattern recognition, we decode it with remarkable accuracy20 as has been shown in studies where listeners can accurately predict the outcome of doctor–patient relationships on the basis of voice tones alone.21

Although some interpersonal strategies are deliberate and consciously employed,22 much interpersonal presentation is a spontaneous expression of inner feelings, attitudes, and values.23 It cannot be effectively feigned or consistently performed in the course of relationship building. When a physician asks a patient, “How are you feeling?” embedded in the question are her convictions about the appropriate doctor–patient hierarchy, her feelings about the particular patient she is addressing, even her level of fatigue. The patient’s response and the relationship that ensues will be shaped by each of these.

In the art of medicine, physicians learn to bring the best of their unique interpersonal capacities to finding a rhythm and resonance with each patient seen in care (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Two Communication Modalities

| Instrumental Communication | Interpersonal Communication | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Transacting the content of health care | Establishing an optimal emotional field |

| Typical channel | Verbal | Non-verbal |

| Language | Abstract symbolic | Iconic-analogic |

| Intentionality | Primarily deliberate | Often spontaneous |

| Assessment source | Expert observer | Participant experience |

| Realm of medical practice | Science of medicine | Art of medicine |

Traditional methods of medical education often do not serve well when teaching IS. In teaching process concepts, what instructors do can have as much impact as what they say. Like professionalism, teaching IS requires careful attention to the “hidden”24 or “process”25 curriculum: role modeling, self-reflection, parallel process, experiential learning, and the teaching context.

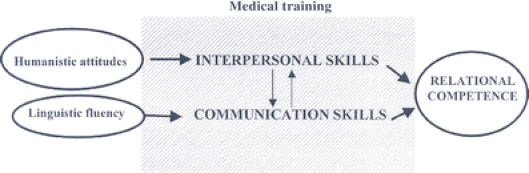

IS development does requires that students bring preexisting humanistic attitudes to the study of medicine. These are identifiable traits,26–28 and, because they are essential to the development of effective physicians, admission committees should be concerned with them. But humanistic attitudes by themselves are not sufficient for the highly demanding transactions that take place in the health care encounter. Students may be interested in their patients’ lives, but will be unable to bring this interest to their practice unless they learn to conduct an efficient interview and are prepared to witness and tolerate patient distress that they cannot relieve. A student’s humanistic attitudes, with support and discipline during medical education, can be developed into interpersonal skills. As they are simultaneously integrated with communication skills, they help the student to acquire competence in relationship building (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Trajectory of relational skill development.

This paper proposes an interpersonal skill-set that corresponds to 3 sequential domains of a physician’s orientation to her patient: cognitive, affective, and behavioral. Each corresponding skill is seen as developing from a core humanistic attitude (see Table 2) and is considered in light of educational approaches that facilitate its development and some related task-oriented communication skills.

Table 2.

An Interpersonal Skill-set

| Domain | Core attitude | Interpersonal skill |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Curiosity | Understanding |

| Affective | Caring | Empathy |

| Behavioral | Respect | Relational versatility |

The educational strategies proposed rest on several assumptions: 1) Because IS are often nonverbal and may not be under conscious control, they cannot be taught using didactic approaches alone; 2) IS learning can be enhanced by attention to the process elements of a communication curriculum; and 3) The goals of the IS component of a communication curriculum should include efforts to nurture a student’s humanism, help her understand her own interpersonal style, and learn to apply it flexibly to the needs of different patients and situations. Whereas a strong argument could be made for restructuring medical education to produce more humanistic physicians, the proposals that follow involve instructional approaches that are not time- or cost-intensive and which are currently used in a number of programs.

UNDERSTANDING

Understanding is the IS through which a patient recognizes that his doctor knows him as a person with his own preferences, hopes, and fears. Understanding involves more than taking a history or constructing a genogram. It also involves respectful curiosity and a desire to learn about the experiences and viewpoints of others.29 Curiosity cannot be feigned. Curious people convey a regard for life’s complexities, distrust fixed opinion, and take joy in surprise.

Teachers can suppress curiosity if they overemphasize memorization and drill, focus on facts rather than experiences, demand students maintain an attitude of expertise, or use humiliation as a motivational tool.30 Learning contexts that nurture curiosity are those that help students assume “the mind of a beginner”,31 teach them to wonder what patient the disease has as well as what disease the patient has,32,33 and encourage them to pursue hunches and search for new solutions to complex problems.34 In this regard, the author has found that having students visit patients in their homes can be a powerful tool for stimulating curiosity and expanding understanding.

An understanding physician must be able to tolerate ambiguity because science’s clear solutions often do not match people’s lives. Students can learn to appreciate the complexity and contradiction of lived experience by exposure to literature35,36 and the lenses of irony, paradox, and humor.37 Learning to explore a patient’s narrative can help a physician develop “the courage to bear witness to life’s unfair losses and random tragedies”.38

The verbal communication skills necessary for curiosity to develop into understanding can be found in the domain of data collection. Establishing focus, exploring the patient’s perspective, taking an accurate history, and narrative checking each act in synergy with the physician’s attitude of curiosity. Verbal communication skills lead to true understanding only if physicians develop the courage and openness to explore their patients’ lives. The Pandora syndrome is an example of how tools become useless without personal readiness.39

EMPATHY

Empathy is the IS through which patients experience their doctor’s consistent, professional concern for their feelings. Empathy has a cognitive aspect—an accurate understanding of a patient’s feelings—and it also necessitates an attitude of caring and an emotional responsiveness to the feeling states of others.40 Empathy is a form of disciplined caring. Unbounded caring could compromise a physician’s judgment. The empathic physician develops a caring that can be sustained through periods of fatigue and personal duress; a caring that is universal, not simply for appealing patients.

Medical educators have begun to recognize that teachers and teaching contexts must model caring, not just discuss it. Teaching caring is best accomplished when faculty model it in their relationships with students. Sustainable caring also requires a level of self-interest.41 Students need to be supported in learning self-care and developing ways to handle their negative feelings. Self-care requires an understanding of one’s own needs and limitations and the ways in which fatigue can signal burnout. It involves an emotional ecology that is personal to the individual physician, her circumstances, and her place in the life cycle.

Caring is not a simple emotion. Freud argued that negative feelings can exist even in our most significant and intimate relationships. Empathy requires that physicians be helped to understand and manage their reactions to the patients they find difficult,42 and to forgive themselves and their patients.43

Physicians must strive to make empathy universal. The best measure of empathy may be the care given to the most undesirable patients. Developing universal caring involves being able to find a commonality with people of very different backgrounds and values and being able to join together around shared human values. Educators have helped students learn to extend their empathic skills by exposing them to diverse populations,44 using patient narratives,45 drama and the performance arts,46 and teaching them to smile.47

Empathy can be verbally communicated by identifying and validating a patient’s feelings,48 and by using strategic self-disclosure, a process in which a physician acknowledges the common bond of humanity she shares with her patients.49,50 There may also be times when a professional boundary or patient care requires the physician to adopt a challenging or distancing stance.

RELATIONAL VERSATILITY

Relational versatility is the ability of the physician to match her interpersonal approach to the communication and relationship needs of different patients,51 to be who and what the patient needs.52 Relational versatility involves the capacity to observe ourselves, the way others experience us and the dynamic that ensues in our various pairings. It is a skill that is built upon an attitude of respect for others, acceptance,53 and an inclination to treat others as we would like to be treated. Respect stimulates self-reflection.54

As the student’s awareness of self and others develops, there is a point where she can begin to see herself and her patient in a single interactive process. From this metaperspective, the nature of relationships in all of their uniqueness and complexity becomes apparent. Our common expression, “the patient–physician relationship” is misleading. Each relationship, like a snowflake, is different from all others. And each relationship is differentially responsive to context. When a routine office visit turns into the discovery of a life-threatening illness, the task of the relationship changes profoundly.

Relational versatility involves a metaperspective that requires students to learn about their own personal style, develop their communication repertoire, and use it flexibly. It modifies the “one size fits all” approach that has troubled many educators.8–10,14,51,52 To be consistently effective in relationships, a physician must know how and when to lead and to follow, whether the dance is a waltz or a tango.

The study of video-taped encounters provides an opportunity for students to obtain a metaperspective on their work with patients.55,56 Importantly, if the focus of this exercise is evaluation, there is a tendency to focus on verbal communication skills rather than considering the unique elements of the relational process.57,58 When video review takes place within a small group of peers and the facilitator emphasizes a noncritical, anthropological perspective (e.g., “Let’s just watch two people talking,”) it encourages participants to discover the diversity in one another’s styles and consider its impact on the patient. Likewise, when faculty facilitators present their own challenging encounters for discussion, it helps to set the stage for students to risk bringing forward their own cases and concerns.

INTERPERSONAL SKILL ASSESSMENT

The final arbiter of IS is the patient. Sometimes professionals’ assessments are at variance with patient judgment. Recently, while observing a patient encounter, I became concerned that the resident was writing in the chart rather than attending to the patient. After the visit, I asked the patient what had been the most important moment in the visit for her. She told me it was when the doctor began writing things down. She could tell then that he was really listening. In this case, my professional judgment and the patients’ differed significantly and although writing in the chart without paying close attention to the patient may generally be viewed as a challenge to the physician–patient relationship, in this case it was “proof” to the patient that the resident was really listening.

The patient’s voice can be difficult to ascertain. Patient satisfaction surveys only identify global aspects of physician behavior and are subject to the distortions of halo and ceiling effects, particularly after the doctor–patient relationship has developed.59 Simulated patient encounters lack the gravity of illness60 and the power imbalance in actual patient care.61 Many assessment approaches are prohibitively expensive or difficult to integrate into training regimens.

One method for assessing physician understanding involves comparing the patient’s and physician’s commentaries on a video tape of their encounter.14 Another educator shares her own patient narratives with the patient for feedback.38 A resident’s grasp of patient concerns can be efficiently evaluated through postvisit checks on patient–physician problem list concordance.62,63

Empathy has been evaluated using patient trust,64 satisfaction,65 adherence,66 and voluntary disenrollment67 as markers. Low malpractice rates68 may indicate patients’ reciprocation of their physician’s empathy. Poor patient show rates can be a flag for a student’s difficulty in conveying empathy.

Assessing relational versatility is complicated by the fact that the patient may perceive it only when it is absent. It can be explored in a case presentation and video review format if instructors ask students to write a third-person narrative account of their work with a patient. This allows for peer discussion of the narrative’s coherence, balance, and complexity,69 and for its correspondence to the videotape.

In conclusion, if we are to heed Roter’s challenge9 and try to move our understanding of the healing relationship beyond a linear, reductionistic model, we must incorporate methods that explore the characteristics and experiences of all participants and the interaction among them. We need to clarify our language, integrate our frameworks, and produce and research new hypotheses about the relationship between communication and interpersonal skills. Our students deserve the best possible training in these skills; our patients deserve no less.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Kim Marvel, Mary Catherine Beach, Larry Mauksch, and Richard Frankel for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges. The Humanism in Medicine Award, Annual Meeting, 2006. Available at:http://www.aamc.org accessed Feb., 2006.

- 2.Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Outcome Project. General Competencies. Available at http://www.acgme.org 2000. Accessed Nov., 2005.

- 3.Makoul G, et al. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: The Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76:390–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Braddock CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidly TL, Leveinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA. 1999;282(24):2313–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on patient outcomes. J Family Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed]

- 6.Street RL. Analyzing communication in medical consultations: do behavioral measures correspond to patients’ perceptions? Med Care. 1992;30(11):976–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Engener B, Cole-Kelly K. Satisfying the patient, but failing the test. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):508–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Zoppi K, Epstein RM. Is communication a skill? Communication behaviors and being in relation. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):319–24. [PubMed]

- 9.Roter DL. Observations on methodological and measurement challenges in the assessment of communication during medical exchanges. Patient Educ Couns. 2003:50(1):17–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Makoul G. The SEGUE framework for teaching and assessing communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45:23–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Boon H, Stewart M. Patient–physician communication assessment instruments: 1986–1996 in review. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;35:161–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Homboe ES, Hawkins RE. Methods for evaluating the clinical competence of residents in internal medicine: a review. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Donnelly MB, Sloan D, Pymale M, Schwartz R. Assessment of residents’ interpersonal skills by faculty proctors and standardized patients: a psychometric analysis. Acad Med. 2000;75:S93–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Duffy FD, et al. Assessing competence in communication and inter-personal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):495–507. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Webster’s Seventh International Dictionary. Springfield, MA: G. and C. Merriam Co, Publishers; 1998.

- 16.Schachner DA, Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Patterns of nonverbal behavior and sensitivity in the context of attachment relationships. J Nonverbal Behav. 2005;29(3):141–69.

- 17.Watzlawick P, Beavin JH, Jackson DD. Pragmatics of Human Communication. New York: Norton and Company, Inc; 1967.

- 18.Scheflen AE. The significance of posture in communication systems. Psychiatry. 1964;27:316–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Birdwhistell RL. Kinesics and Context: Essays on Body Motion Communication. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1970.

- 20.Gladwell M. Blink. New York: Little, Brown and Co; 2004.

- 21.Ambady N, Laplante D, Nguyen T, Rosenthal R, Chaumeton N, Levinson W. Surgeons’ tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132:5–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Coulehan JL, Block ML. The Medical Interview: Mastering the Skills for Clinical Practice. Philadelphia: FA Davis Co; 2006.

- 23.Goffman E. Behavior in Public Places. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press; 1963.

- 24.Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum; ethics teaching and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69(11):861–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Haidet P and Stein HF. The role of the student–teacher relationship in the formation of physicians: the hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.McLeod PJ, Tamblyn R, Benaroya S, Snell L. Faculty ratings of resident humanism predict satisfaction ratings in ambulatory medical clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:321–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Hornblow AR, Kidson MA, Jones KV. Measuring medical students’ empathy: a validation study. Med Educ. 1977;11:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Winfield HR, Chur-Hansen A. Evaluating the outcome of communication skill teaching for entry-level medical students: does knowledge of empathy increase? Med Educ. 2000;34:90–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Dyche L, Zayas L. The value of curiosity and naivete for the cross-culture psychotherapist. Fam Proc 1995;35(4)389–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Fitzgerald FT. Curiosity. Ann Int Med. 1999;130(1):70–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Borell-Carrio F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice and scientific inquiry. Arch Fam Med. 2004;2(6):576–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Barondess JA. Viewpoint: on wondering. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):62–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Stone MJ. The wisdom of Sir William Osler. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(4)269–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Epstein RM. Mindful practice in action (II): cultivating habits of mind. Fam Syst Health. 2003;21(1):11–7.

- 35.Richardson R. Keat’s notebook. Lancet. 2001;357(25):320. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Wear D, Nixon LL. Literary inquiry and professional development in medicine. Perspect Biol Med. 2002;45(1):104–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Berger JT, Coulehan J, Belling C. Humor in the physician–patient encounter. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(8):825–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–1902. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.McCauly J, Yurk RA, Jenckes MW, Ford DE. Inside “pandora’s box:” abused womens’ experiences with clinicians and health services. J Gen Int Med. 1998;13(8):549–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M. Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry. 2002:159:1563–69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Shanafelt TD, West C, Zhao X, et al. Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced empathy among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):559–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Novack DH, Suchman AL, Clark W, et al. Calibrating the physician: personal awareness and effective medical care. JAMA. 1997;278(6):502–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Macaskill A, Maltby J, Day L. Forgiveness of self and others and emotional empathy. J Soc Psychol. 2002;142(5):663–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Falicov CJ. Training to think culturally: a multidimensional comparative framework. Fam Proc. 1995;35(4):373–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Charon R. Medicine, the novel and the passage of time. Ann Int Med. 2000;132:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Larsen EB, Yao X. Clinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient–physician relationship. JAMA. 2005;293(9):1100–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Borell-Carrio F. The depth of a smile. Medical Encounter. 2000;15:13–4.

- 48.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca, RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(17):1877–84. [PubMed]

- 49.Candib L. What doctors tell about themselves to patients: implications for intimacy and reciprocity in the relationship. Fam Med. 1987;19:23–30. [PubMed]

- 50.Frank E, Breyan J, Elon L. Physician disclosure of healthy personal behaviors improves credibility and ability to motivate. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:287–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM. Optimal matches of patient preference for information, decision-making and interpersonal behavior: evidence, models and interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(3):319–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Zinn WM. Transference phenomena in medical practice: being whom the patient needs. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:293–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Branch WT. Viewpoint: teaching respect for patients. Acad Med. 2006;81(5):463–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Novack DH, Epstein RM, Paulsen RH. Toward creating physician-healers: fostering medical students’ self awareness, personal growth and well-being. Acad Med. 1999;74:516–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282(9):833–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Beckman HB, Frankel RM. The use of videotape in internal medicine training. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:517–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Edwards A, Tzelepis A, Melgar T, et al. Fifteen years of a videotape review program for internal medicine and medicine-pediatrics residents. Acad Med. 1996;71(7):744–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Roter DL, Larson S, Shinitzky H, et al. Use of an innovative video feedback technique to enhance communication skills training. Med Educ. 2005;37(2):145. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Schirmer JM, Mauksch L, Lang F, et al. Assessing communication competence: a review of current tools. Fam Med. 2005;37(3):184–92. [PubMed]

- 60.Hodges B, Turnbull J, Cohen R, Bienenstock A, Norman G. Evaluating communication skills in the objective structured clinical examination format: reliability and generalizability. Med Educ. 1996;30:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Hanna M, Fins JJ. Viewpoint: power and communication: why simulation training ought to be complemented by experiential and humanist learning. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):265–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Friedan RB, Goldman L, Cecil RR. Patient–physician concordance in problem identification in the primary care setting. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:490–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Dyche L, Swiderski D. The effect of physician solicitation approaches on ability to identify patient concerns. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:267–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Thom DH, Cambell B. Patient–physician trust: an exploratory study. J Fam Pract. 1997;44(2):169–76. [PubMed]

- 65.DiMatteo MR, Hays R. The significance of patients’ perceptions of physician conduct: a study of patient satisfaction in a family practice center. J Community Health. 1980;6(1):18–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Eisenthal S, Emory R, Lazare A. “Adherence” and the negotiated approach to patienthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:393–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Safran DG, Montgomery JE, Chang H, Murphy J, Rogers WH. Switching doctors: predictors of voluntary disenrollment from a primary physician’s practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):130–6. [PubMed]

- 68.Levinson W, Rotor DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician–patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Fiese BH, Sameroff AJ, Grotevant HD, et al. (eds.). The stories that families tell: narrative coherence, narrative interaction, and relationship beliefs. Monographs of the society for research in child development. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 1999:64(2 serial No. 257).