Abstract

CASE REPORT

A 74-year-old farmer presented with worsening headaches, gait unsteadiness, and writing difficulties. On examination, he had a tendency to fall to the right and right-sided dysmetria and dysdiadochokinesis. Magnetic resonance imaging initially showed abnormalities in the right cerebellar hemisphere, suggestive of subacute infarct or infiltrating malignancy. Suboccipital craniotomy and biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas suggestive of sarcoidosis. He was initially treated with steroids and later switched to Infliximab. On follow-up 5 months later, symptoms and imaging had improved.

DISCUSSION

Sarcoidosis affects the central nervous system in about 5% of patients. It usually manifests with cranial nerve palsies. It may rarely mimic a tumor as in this patient. Despite the dearth of controlled studies addressing neurosarcoidosis treatment, excellent responses to corticosteroids have been documented. Infliximab has been used as a steroid-sparing agent in neurosarcoidosis. We present this case of neurosarcoidosis presenting as a cerebellar mass to increase awareness of this condition.

KEY WORDS: neurosarcoidosis, Infliximab, cerebellar mass

INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is an idiopathic multisystemic disease that may affect any part of the central nervous system (CNS) that was first described in 1899.1 The presence of clinical CNS involvement has been estimated to be around 5%.2,3 Sarcoidosis occurs worldwide and affects people of all races, both genders, and all ages.

Neurosarcoidosis may present acutely or in an indolent fashion. Any part of the CNS may be involved but cranial nerves, the pituitary gland, and the hypothalamus are the most common.2 One third of patients have multiple neurological lesions.

The diagnosis is usually clear if a patient with known systemic sarcoidosis presents with neurological symptoms and suggestive imaging studies. However, without biopsy evidence at other sites, CNS neurosarcoidosis is difficult to diagnose.4 We present this case of neurosarcoidosis presenting as a cerebellar mass to increase awareness of this unusual presentation of this disease.

CASE REPORT

We present a 74-year-old retired white male farmer with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and impaired glucose tolerance. He experienced recent worsening of chronic occipital headaches over a 6-month period. These headaches radiated to the upper neck and were described as daily “thudding” headaches that were 8–9/10 in severity. He initially had diplopia, diagnosed as a left third nerve palsy, which completely resolved after 5–6 weeks. He denied any other vision or hearing changes, including photophobia. He had managed these headaches with acetaminophen and ice packs. Subsequently, he experienced disequilibrium, described as unsteady gait, difficulty in writing, and toppling over when bending down.

His heart, lung, abdominal, and peripheral vascular exams were unremarkable. His neurological exam was significant for right-sided dysmetria and dysdiadochokinesis. On gait testing, he also tended to fall to the right.

Prior evaluation at an outside hospital when he presented with diplopia 6 months ago included workup for myasthenia gravis, which was negative for antinicotinic acetylcholine receptor antibodies and edrophonium test. By report, an outside magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan taken 5 months into symptom onset (1 month before our evaluation) showed an abnormal signal within the inferior and superior right cerebellar hemisphere with areas of contrast enhancement, which were concerning for subacute infarct or infiltrating malignancy. Outside CT chest/abdomen/pelvis revealed mild retroperitoneal paraaortic lymphadenopathy, with the largest node measuring 2.3 cm. Because these findings merited neurosurgical evaluation, he was transferred to our center for further evaluation.

Repeat MRI at our center showed T2 hyperintensity with enhancement in the right cerebellar hemisphere. See Figure 1a. Diffusion-weighted imaging showed increased signal intensity. There was heterogeneous contrast enhancement. The involved area did conform to the territory of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery and there was mass effect on the fourth ventricle. Initially, we planned to follow this serially with repeat imaging. Repeat MRI 1 month later showed little change. The stable MRI findings suggested an infiltrative process rather than an infarct and the decision to proceed to biopsy was made.

Figure 1.

a Postgadolinium T1-weighted image of the cerebellum showing heterogenous enhancement at the peripheral portions of the lesions. There appears to be some leptomeningeal enhancement superiorly. b Postgadolinium T1-weighted image of the cerebellum showing decreased size of the mass lesion and resolution of the pressure effect on the fourth ventricle.

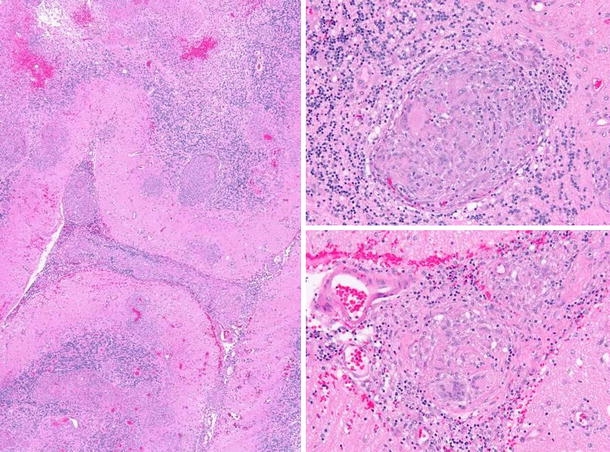

Biopsy of his cerebellar mass showed a marked chronic inflammatory process characterized by nonnecrotizing granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The inflammatory process involved both leptomeninges and parenchyma. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Multiple nonnecrotizing granulomas characterized by epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells are present in leptomeninges and cerebellar parenchyma.

He was then started on high-dose steroids. He was readmitted to hospital 1 month later because of a pulmonary embolism. Concurrently, he had developed steroid-induced hyperglycemia and worsening hypertension. Immunosuppressive therapy was required for at least 1 year. Because he had significant metabolic side effects after just 1 month and had a history of coronary artery disease, he was switched to Infliximab to minimize these adverse effects. A repeat MRI performed 6 months later showed improvement in the cerebellar lesion. See Figure 1b. At that time, his gait ataxia, writing difficulties, and unsteadiness had resolved completely. However, on exam, he had very mild residual dysmetria.

DISCUSSION

Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Thus, it is important to consider a broad spectrum of disorders, which may indeed be more common than neurosarcoidosis. Our patient presented with right-sided cerebellar signs. The differential diagnosis includes a variety of causes: infiltrating neoplasms (such as lymphomas, metastases, and gliomas), infectious etiologies (including encephalitis or tuberculosis), and inflammatory causes (such as demyelinating disorders). The gradual onset of symptoms suggests a neoplastic or infiltrative process as the etiology rather than an infarction or hemorrhage. The symptom progression also suggests that an infarction is unlikely, as deficits because of infarctions are typically of maximal severity at onset.

Neurosarcoidosis usually develops in the leptomeninges and results in disruption of the leptomeningeal blood–brain barrier, permitting the granulomatous inflammation to penetrate the brain parenchyma along the perivascular spaces of Virchow–Robin accompanying the penetrating vessels.5

MRI manifestations of neurosarcoidosis are protean and nonspecific.6 The most common abnormality is leptomeningeal enhancement with parenchymal periarterial enhancement. The clinical manifestations of neurosarcoidosis are summarized. See Table 1. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there has been only 1 previous case report of neurosarcoidosis presenting as a cerebellar syndrome.7 The presence of focal leptomeningeal enhancement in this patient also helps to point toward the diagnosis.

Table 1.

Neurological Manifestations of Sarcoidosis

| Involvement | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Cranial neuropathies | 50–75 |

| II | 15 |

| VII | 25–50 |

| VIII | 10–20 |

| Meningeal disease | 10–20 |

| Hydrocephalus | 10 |

| Parenchymal disease | 50 |

| Endocrinopathy | 10–15 |

| Mass lesion | 5–10 |

| Encephalopathy/Vasculopathy | 5–10 |

| Seizures | 5–10 |

| Neuropathy | 15 |

| Myopathy | 15 |

The prevalence shown is that among all patients with neurosarcoidosis.

Adapted from Stern.19

Treatment with corticosteroids forms the mainstay for neurosarcoidosis.8 The dosage used in the treatment of neurosarcoidosis is higher than in systemic sarcoidosis. Response to steroids is usually good but treatment failures do occur. In patients in whom steroids are contraindicated, cytotoxic agents such as methotrexate,9 azathioprine, cyclosporine,10 and cyclophosphamide11 have been used. Unfortunately, given the rarity of the disease, the choice of agents has been based on experience rather than on randomized, controlled trials. Methotrexate appears to be the most widely used drug and is rather well-tolerated, although regular monitoring is needed for hepatic toxicity.

Immunomodulating agents have also been used in the treatment of neurosarcoidosis. In some patients with neurosarcoidosis, the use of antimalarials (chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine) has been beneficial.12 It has been found that tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels are elevated in patients with active pulmonary sarcoidosis and that these levels decline with corticosteroid or methotrexate treatment.13 The human–mouse chimeric anti-TNF-α antibody Infliximab has been shown to be effective both as a steroid-sparing agent and in patients with refractory sarcoidosis.14,15 In a recent retrospective study on 10 patients who received infliximab for sarcoidosis, which included patients with neurological manifestations16, there was a low occurrence of adverse effects. Only 1 patient developed an anaphylaxis-like syndrome that was thought to be related to the development of human antichimeric antibodies. Latent histoplasmosis and tuberculosis may be reactivated by Infliximab use. The development of lymphoproliferative disorders has also been associated with the use of Infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn’s disease.17 We opted for Infliximab therapy in our patient only after carefully balancing these issues against the adverse effects of steroid therapy (worsening hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia) in the presence of coronary artery disease with quadruple coronary artery bypass surgery 6 years ago.

Neurosurgical resection of intracranial granulomas is only indicated in life-threatening situations or when medical therapy is inadequate. Ventriculoperitoneal shunts are sometimes needed in patients with hydrocephalus.18

Neurosarcoidosis is a rare disease with multiple manifestations. It may present as an isolated cerebellar mass mimicking a tumor, as in this case. There have been several case reports about this disease but not much progress has been made on the management of this enigmatic disease because of its rarity and the paucity of clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Boeck C. Multiple benign sarcoid of the skin. J Cutan Genito-Urin Dis. 1899;17:543–50.

- 2.Stern BJ, Krumholz A, Johns C, Scott P, Nissim J. Sarcoidosis and its neurological manifestations. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:909–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Delaney P. Neurologic manifestations in sarcoidosis: review of the literature, with a report of 23 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:336–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kidd D, Beynon HL. The neurological complications of systemic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20:85–94. [PubMed]

- 5.Mirfakhraee M, Crofford MJ, Guinto FC, Nauta HJ, Weedn VW. Virchow–Robin space: a path of spread in neurosarcoidosis. Radiology. 1986;158:715–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mana J. Magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear imaging in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8(5):457–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wiesli P, Hess K, Cathomas G, Stey C. Neurosarcoidosis presenting as cerebellar mass. Eur Neurol. 2000;43(1):58–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Oksanen V. Neurosarcoidosis: clinical presentation and course in 50 patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1986;73:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Baughman RP, Lower EE. A clinical approach to the use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1999;54:742–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Stern BJ, Schonfeld SA, Sewell C, Krumholz A, Scott P, Belendiuk G. The treatment of neurosarcoidosis with cyclosporine. Arch Neurol. 1991;49:1065–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Doty JD, Mazur JE, Judson MA. Treatment of corticosteroid-resistant neurosarcoidosis with a short-course cyclophosphamide regimen. Chest. 2003;124:2023–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Sharma OP. Effectiveness of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in treating selected patients with sarcoidosis with neurological involvement. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1248–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Baughman RP. Therapeutic options for sarcoidosis: new and old. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8:464–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Sollberger M, Fluri F, Baumann T, et al. Successful treatment of steroid-refractory neurosarcoidosis with infliximab. J Neurol. 2004;251(6):760–1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB, Bognar B. Refractory neurosarcoidosis: a dramatic response to infliximab. Am J Med. 2004;117(4):277–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Doty JD, Mazur JE, Judson MA. Treatment of sarcoidosis with infliximab. Chest. 2005;127(3):1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Browne SL, Greene MH, Gershon SK, Edwards ET, Braun MM. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy and lymphoma development: twenty-six cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(12):3151–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Foley KT, Howell JD, Junck L. Progression of hydrocephalus during corticosteroid therapy for neurosarcoidosis. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:481–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Stern BJ. Neurological complications of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:311–6. [DOI] [PubMed]