Abstract

BACKGROUND

Systems of undergraduate medical education and patient care can create barriers to fostering caring attitudes.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study is to survey associate deans and curriculum leaders about teaching and assessment of caring attitudes in their medical schools.

PARTICIPANTS

The participants of this study include 134 leaders of medical education in the USA and Canada.

METHODS

We developed a survey with 26 quantitative questions and 1 open-ended question. In September to October 2005, the Association of American Medical Colleges distributed it electronically to curricular leaders. We used descriptive statistics to analyze quantitative data, and the constant comparison technique for qualitative analysis.

RESULTS

We received 73 responses from 134 medical schools. Most respondents believed that their schools strongly emphasized caring attitudes. At the same time, 35% thought caring attitudes were emphasized less than scientific knowledge. Frequently used methods to teach caring attitudes included small-group discussion and didactics in the preclinical years, role modeling and mentoring in the clinical years, and skills training with feedback throughout all years. Barriers to fostering caring attitudes included time and productivity pressures and lack of faculty development. Respondents with supportive learning environments were more likely to screen applicants’ caring attitudes, encourage collaborative learning, give humanism awards to faculty, and provide faculty development that emphasized teaching of caring attitudes.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of educational leaders value caring attitudes, but overall, educational systems inconsistently foster them. Schools may facilitate caring learning environments by providing faculty development and support, by assessing students and applicants for caring attitudes, and by encouraging collaboration.

KEY WORDS: caring attitudes, medical education, hidden curriculum, professionalism

INTRODUCTION

The first American Medical Association Code of Ethics, written in 1847, underscored physicians’ professional commitment to treat every patient with “attention, steadiness, and humanity.”1 In this century, a large body of evidence demonstrates that effective interpersonal relationships and communication enhance patients’ clinical outcomes2,3 trust and medical adherence4–6 while decreasing malpractice litigation7,8 and diagnostic testing expenditures.9 Prominent organizations have called for increased efforts to teach and support caring, professional relationships in educational and clinical practice settings.10–12 Patients, physicians, educators, and policy makers also assert that current systems of medical education and patient care create barriers to the expression of caring attitudes.13,14 Finally, in addition to what trainees learn in the classroom, clinicians and educators have described a “hidden curriculum” that trainees learn by watching what those teaching them do, not what they say, and can negatively affect attitudes and behaviors of students and their professional formation.15–18

Despite these voices of concern, little is known about how medical schools actually foster and assess caring attitudes. Recently, the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations commissioned the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare to study this important but elusive topic. We report results of a survey of Associate Deans and curriculum leaders at medical schools across the USA and Canada.

METHODS

Questionnaire Development and Administration

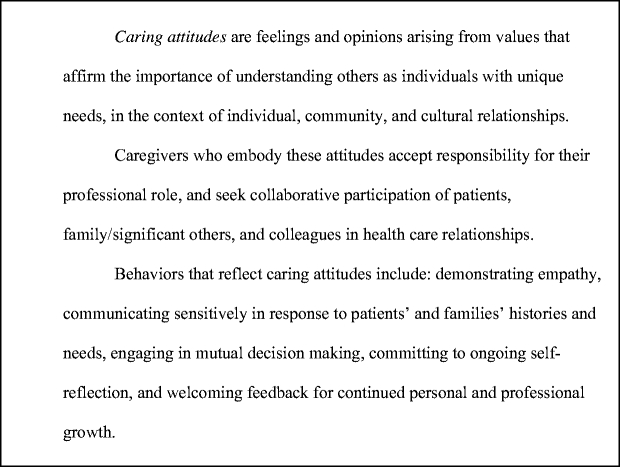

Six of the authors (B.L., C.L.C., W.C., P.H., M.K.W., P.W.) participated in 7 rounds of discussion to create a definition of “caring attitudes.” We then solicited the comments of 10 invited reviewers with backgrounds in medicine, psychology, education, and patient advocacy and revised the definition until reaching consensus (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Definition of caring attitudes

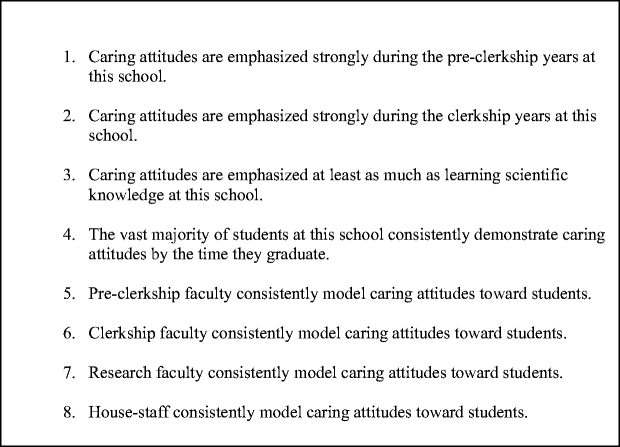

From this definition, we created a survey for curriculum deans that included 26 quantitative and 1 open-ended qualitative question (Appendix 1). To have a reliable indicator of the social climate of each school, we selected 8 items encompassing emphasis, demonstration, and modeling of caring attitudes and combined them into a “Social Climate Index” (SCI; Fig. 2) with strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80).

Figure 2.

Social Climate Index (SCI)

Invitations and a link to our web-based survey were e-mailed to deans, associate deans of medical education or curricular affairs, or their designees at 134 medical schools in the USA and Canada. A follow-up reminder was e-mailed 1 month later. Responses were collected anonymously through a web-based survey platform. We intended to send 1 invitation to each medical school in the USA and Canada, but 2 of 125 US medical schools and 6 of 17 Canadian medical schools were unintentionally omitted. In addition, duplicate invitations were unintentionally sent to 2 different individuals at 26 institutions, and to 3 different individuals at 3 institutions. Because the responses were anonymous, we could not determine whether more than 1 response was received from each of these schools.

Data Analysis

For each of the quantitative questions, we calculated frequencies according to category of response and mean scores, as appropriate. To calculate the SCI, we summed the 4-point Likert ratings for each of the 8 items. Total SCI scores could, therefore, range from 8–32. We divided these scores at the median. Lower SCI responders had index scores of ≤23 (n = 33) and higher SCI responders had scores of ≥24 (n = 40). We compared responses of the lower SCI-responder group to the higher SCI-responder group for each survey question using the chi-square statistic.

To analyze responses to the open-ended qualitative question about relationship-building and the effects of hidden curricula, 4 members of the research team (B.L., C.L.C., M.K.W., P.W.) used an approach informed by grounded theory19 to (a) develop an initial list of themes from the comments, (b) revise the themes using the constant comparison method,19 and (c) code each comment until consensus was reached that all comments were represented within appropriate themes. We then counted the frequency of comments within each theme.

RESULTS

Quantitative Analysis

Of 134 medical schools surveyed, we received 73 responses, representing a response rate between 54% (if none of the duplicate surveys were returned) and 31% (if all of the duplicate surveys were returned). There were no statistically significant differences (0.05 confidence level) between the respondents in our sample and the entire cohort of North American medical schools based on region, class size, and public versus private institution. The majority of respondents (70%) self-identified as associate or vice deans (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents, n = 73

| Characteristic | National statistics % (n) | Survey respondents % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Respondent | ||

| Dean | 1% | |

| Associate Dean of Medical Education and/or Curricular Affairs | 70% | |

| Other | 30% | |

| School type | ||

| Public | 60% (75) | 67% (49) |

| Private | 40% (50) | 33% (24) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 28% (35) | 26% (19) |

| Midwest | 25% (31) | 26% (19) |

| South | 34% (43) | 38% (28) |

| West | 13% (16) | 10% (7) |

| Class Size | ||

| <100 | 24% (30) | 16% |

| 101–150 | 38% (47) | 41% |

| >150 | 38% (48) | 43% |

National statistics were derived from databases from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

We first explored beliefs about caring attitudes and perceptions about their prevalence (Table 2). Seventy-three percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that caring attitudes are difficult to teach if students do not possess them upon entering medical school. Whereas most believed that their medical schools’ curricula strongly emphasized caring attitudes, one third disagreed that they were emphasized as much as scientific knowledge. Respondents believed clerkship faculty appeared to model caring attitudes most consistently, followed by preclerkship faculty, house staff, and research faculty.

Table 2.

Perceptions About Emphasis and Prevalence of Caring Attitudes

| Question | Strongly agree or agree % (n) | Strongly disagree or disagree % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Emphasis: Caring attitudes at this school are emphasized | ||

| Strongly during the preclerkship years | 89 (65) | 11 (8) |

| Strongly during the clerkship years | 90 (66) | 10 (7) |

| At least as much as learning scientific knowledge | 65 (47) | 35 (25) |

| Demonstration: | ||

| The vast majority of students demonstrate caring attitudes by the time they graduate | 96 (69) | 4 (3) |

| Virtually all or most % (n) | Some or very few % (n) | |

| Modeling: How many consistently model caring attitudes toward students? | ||

| Preclerkship faculty | 79 (57) | 21 (15) |

| Clerkship faculty | 86 (62) | 14 (10) |

| Research faculty | 46 (32) | 54 (37) |

| House staff | 70 (22) | 30 (21) |

The most frequently reported organizational symbol of support for caring attitudes was awards to recognize faculty humanism. Three-quarters of schools ask admissions interviewers to assess caring attitudes in medical school applicants, but only 25% of those train them to do so.

During the preclerkship years, the most frequently reported methods for teaching caring attitudes included small-group discussions (81%), skills training or feedback on directly observed skills (66%), and didactic sessions (48%). During the clerkship years, the predominant methods included role modeling (84%), skills training or feedback on directly observed skills (67%), and mentoring (43%). Sixty-four percent of respondents said that virtually all or most students have an ongoing formal mentoring relationship with a faculty member.

Table 3 shows methods schools use to assess caring attitudes in order of frequency. Sixty-eight percent of respondents reported that they had defined competency requirements for demonstrating caring attitudes. Almost all surveyed schools had a clinical skills examination. The majority of respondents indicated that at least 20% of the students’ grade on the clinical skills examination depended on interpersonal and communication skills.

Table 3.

Assessment Methods

| Method | % (n) |

|---|---|

| OSCE | 82 (60) |

| Faculty observations of students’ interactions with patients & families | 70 (51) |

| Faculty observations of students’ interactions with other students | 48 (35) |

| Reports from house staff | 44 (32) |

| Faculty observations of students’ interactions with healthcare teams | 29 (21) |

| Case presentations | 21 (15) |

| Students’ peer review | 11 (8) |

| Patients’ and families’ comments | 6 (4) |

| Health professionals’ observations | 4 (3) |

Respondents selected 3 predominant methods used at their schools, therefore, percents do not sum to 100%.

Fifty-four percent of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that their faculty development programs emphasized the recognition and teaching of caring attitudes. Table 4 lists the frequency of faculty development offerings over the past year. Programs oriented more specifically toward recognizing and fostering caring attitudes were named less frequently.

Table 4.

Percent of Schools Offering Faculty Development Programs in Specified Topics

| Faculty development program | % (n) |

|---|---|

| General teaching skills | 82 (60) |

| Giving and receiving feedback | 78 (57) |

| Group facilitation skills | 55 (40) |

| Teaching professionalism | 51 (37) |

| Communication skills | 47 (34) |

| Cultural sensitivity | 45 (33) |

| Mentoring skills | 27 (20) |

| Facilitating self-reflection and personal awareness | 18 (13) |

| Physician wellness | 11 (8) |

| Facilitating caring attitudes in students | 8 (6) |

When asked to identify the 3 most significant barriers to teaching or enhancing students’ caring attitudes, respondents most frequently cited time and productivity pressures, lack of faculty development and expertise, and the perception that faculty believed current teaching was adequate.

We compared policies and practices of schools at which caring was perceived to be more strongly emphasized (high SCI scores) to those where it was less so (low SCI scores) and found significant differences. Table 5 shows responses to the quantitative questions that significantly differed between these schools. Differences encompassed a broad range of opportunities to assess and encourage teaching of caring attitudes.

Table 5.

Differences in Emphasizing Caring Attitudes in Schools with Low Versus High Social Climate Index

| Question | Responsea | Total % (n) | Lower SCI responders, n = 33 % (n) | Higher SCI responders, n = 40 % (n) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students are strongly encouraged to engage in collaborative learning at this school | Agree | 94 (68) | 88 (29) | 100 (39) | 0.025 |

| Disagree | 6 (4) | 12 (4) | 0 | ||

| Faculty development programs strongly emphasize recognition/teaching caring attitudes | Agree | 54 (39) | 31 (10) | 72 (29) | 0.002 |

| Disagree | 46 (33) | 69 (22) | 28 (11) | ||

| School asks interviewers to assess caring attitudes of applicants | Yes | 93 (55) | 85 (22) | 100 (33) | 0.020 |

| No | 7 (4) | 15 (4) | 0 | ||

| Annual faculty awards for caring/ humanism | Yes | 77 (56) | 64 (21) | 88 (35) | 0.016 |

| No | 23 (17) | 36 (12) | 12 (5) | ||

| OSCE chosen as one of the top three methods to assess caring attitudes | Yes | 82 (60) | 70 (23) | 92 (37) | 0.011 |

| No | 18 (13) | 30 (10) | 8 (3) | ||

| Provided faculty development within past year in facilitating self-reflection/ personal awareness | Yes | 18 (13) | 6 (2) | 28 (11) | 0.017 |

| No | 82 (59) | 94 (31) | 72 (28) |

aWe collapsed responses agree/strongly agree into a single “agree” category, and disagree/strongly disagree into a single “disagree” category.

Qualitative Analysis

Eighty-eight percent of survey respondents replied to an open-ended question that asked how schools address their hidden curricula and ensure that students master advanced relationship-building skills. There were 139 comments contained in the 64 responses. These were coded into 9 themes (Table 6).

Table 6.

Theme Frequency Counts

| Themes | Number of comments per theme |

|---|---|

| Approaches to teaching relationship building skills and caring attitudes | 80 |

| Attention to specific content and objectives | 65 |

| Approaches to assessment | 26 |

| Formal structures or policies | 16 |

| Barriers | 12 |

| Faculty or resident evaluation by students | 8 |

| Faculty or resident training | 7 |

| Reward and recognition for faculty | 3 |

| Engagement and support of leadership | 4 |

The most frequent theme was “approaches to teaching relationship skills and caring attitudes.” Faculty modeling and small-group discussion were the most commonly used methods to teach about communication and professionalism, to facilitate reflection, and to discuss the patient–physician relationship within a wider social context. Eleven respondents noted the importance of teaching across the continuum from undergraduate to postgraduate medical education. Methods to achieve this included integrating specific communication and professionalism competencies, creating committees (with preclinical and clinical faculty and student representatives) to implement competencies, having consistent faculty mentors or mentoring groups in place for all 4 years of undergraduate education, and addressing the hidden curricula within residency programs. Four respondents described planned activities to provide students with opportunities to discuss examples of unprofessional, uncaring behaviors:

...we provide...opportunities built into the clerkships in protected environments away from residents and attending faculty for medical students to discuss real experiences...of bad examples of caring attitudes.... Student reactions in discussing and seeking validation of their perceptions of such examples may be as effective in steeling their determination to avoid slipping into such attitudes as the positive examples of role models for caring attitudes.

Only 3 comments mentioned the role of institutional leadership and key faculty in establishing standards and establishing a social climate that supports caring attitudes. We did not explicitly ask about barriers in the open-ended question, but 12 individuals mentioned them. Several quotes exemplified the perspective that caring attitudes cannot be taught if students do not matriculate with them:

Students are either attuned to this type of behavior or they are not. About the best we can do is to weed out the very worst and try to model the best behavior.

The remaining comments about barriers fell into 3 domains: funding and productivity pressures, competing or lack of integration of the interests of the medical school and the clinical departments, and inertia:

The pressures of reduced state and federal support and cutbacks in reimbursement rates have forced medical schools to focus on increasing clinical revenues and research grant and contract efforts in order to remain solvent. Therefore, the emphasis and resources often go to faculty who are good at generating revenue rather than being good role models for caring attitudes. Even if the undergraduate medical education deans are fully supportive, it is beyond their control, because clinical department chairs hire those faculty who can keep their departments in the black, and the faculty who are best at that often do not want to teach or are pressured to generate revenue rather than teach.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, ours is the first survey to ask educational leaders specifically about teaching and assessing caring attitudes, although 2 prior surveys asked about the related topic of teaching and assessing healthcare communication.20,21 While our overall results suggest that a majority of medical school leaders value caring attitudes, the details of our survey suggest inconsistent implementation of these values in admissions, teaching, assessment, and faculty development processes. In addition, senior educators noted a number of explicit barriers to fostering students’ caring attitudes, including time and productivity pressures, insufficient faculty development, and lack of integration of the educational and financial needs and goals of medical schools and their affiliated hospitals. Finally, while we cannot draw any causal inferences from the SCI results, they do indicate a definite association between emphasis and demonstration of caring attitudes and institutional policies and practices. Several of the most important challenges to fostering caring attitudes are discussed below.

Admissions Processes

Most respondents expressed pessimism about fostering caring attitudes in students who do not already possess them. This opinion echoes recent studies showing that students who demonstrate unprofessional behavior in medical school have an increased likelihood of disciplinary action by state medical boards later in their careers.22 Some schools have begun to provide explicit faculty training in assessing medical school applicants for attributes related to professional values.23 However, the vast majority in our survey do not, leaving the screening to individual interviewers’ discretion rather than a carefully considered, standardized process.

Teaching Methods

Because caring attitudes are demonstrated within the context of relationships, the most appropriate methods to teach them are those that bring teachers and students into close contact. Most schools appear to reinforce caring attitudes in small groups through students’ observations of faculty role models and through faculty observation and feedback to students during skills training sessions. The high frequency of schools reporting that they teach caring attitudes in didactic sessions likely reflects the predominance of this method in the preclinical curriculum rather than its suitability for teaching attitudes.

In the clerkship years, the primary teaching methods shifted to role modeling and mentoring. Our finding that 64% of respondents report ongoing student mentoring mirrors students’ responses to the AAMC graduation questionnaire results in 2005, in which 67% of students indicated that they were satisfied with faculty mentoring.24 When the same survey asked students where professionalism and compassion (attributes closely related to caring attitudes) were emphasized, they reported role modeling less than 12% of the time.24 Our study provides a possible explanation for this discrepancy: In most academic health centers, students spend most of their clinical time with house staff who, in our survey, rated below preclerkship and clerkship faculty in their role modeling of caring attitudes.25,26 Future studies must describe and assess methods to promote caring attitudes in graduate medical education.

Assessment

Objective assessment of attitudes is challenging and complex. The high proportion of respondents emphasizing interpersonal and communication skills in their clinical skills examinations suggests that these skills currently serve as observable behavioral manifestations of caring attitudes. Medical schools rely increasingly on objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE) as the main assessment method, with 16% of schools reporting the use of OSCE in a 1993 survey,21 70% in 1999,20 and 82% in our survey. Respondents from schools with higher SCI scores were significantly more likely to name OSCE as a predominant assessment method. Contrary to recent calls for 360° assessment of student attitudes and behaviors,25 respondents noted significant de-emphasis of student peer review (38% in 1999 compared with 11% in our study) and assessments by nurses and other allied health professionals (24% versus 4%).20 Systematic methods for including the perspectives of multiple observers within actual healthcare teams could provide contextual assessment and help educators correlate actual with simulated performance.27–29

Faculty Development

Faculty development is essential to enhance teachers’ abilities to foster caring attitudes. In a 1993 survey, opportunities for faculty development in teaching communication and interpersonal skills were the most frequently cited enhancement desired by medical school deans.21 Our results suggest that faculty development remains insufficient. Whereas 54% of respondents concurred with the statement that their faculty development programs strongly emphasized recognition and teaching of caring attitudes, less than half indicated that they actually provide faculty development in teaching communication and mentoring skills. Only 8% reported offering faculty development activities focusing specifically on how to foster caring attitudes. Additionally, 56% of respondents cited a lack of faculty development and expertise as a barrier to teaching caring attitudes, a slightly higher percentage than the 50% indicated by deans in the 1993 survey.21

Interestingly, 3 of the 6 variables that significantly differentiated between high- and low-SCI schools pertained to faculty recognition and development. We also found an intriguing correlation between SCI score and type of faculty development offered. Specifically, high-SCI schools were more likely to offer programs to help faculty facilitate self-reflection and personal awareness among students. As some qualitative comments suggest, personal awareness is critically important in counteracting hidden curricula. Learners may need explicit guidance to understand how their attitudes, emotions, values, and behaviors affect their interactions and personal development.30–32

Barriers

Prior studies suggest that time pressure is a barrier to humanistic care of patients and contributes to physician stress and burnout.33 It is not surprising that time pressure, coupled with a paucity of specifically designed faculty development programs, leaves educators feeling similarly pessimistic about their ability to teach caring attitudes in today’s clinical environment. Formal sessions to teach caring attitudes may be unnecessary, however, if faculty can efficiently and effectively incorporate teaching strategies into everyday clinical activities.34,35

Another major barrier is demands for increased productivity. Respondents’ comments described their frustration that clinical and research revenue generation trumps education. Indeed, financial pressures and weak institutional alignment of interests and goals are important challenges to leaders of academic medical centers.36 Both time and productivity pressures likely figure heavily in the power of hidden curricula.

Hidden Curricula

Our survey substantiates educators’ perceptions that hidden curricula undermine caring attitudes. Over one third of respondents indicated that a hostile clinical learning climate and a lack of importance attributed to teaching caring attitudes were significant barriers. Respondents described methods to counteract hidden curricula, but also expressed a sense of pessimism about addressing underlying systemic issues. Students attest to the persistent presence of “uncaring attitudes” by reporting episodes of personal mistreatment on AAMC graduation questionnaires—most frequently, being publicly belittled or humiliated.24 The number of students reporting these episodes is small, but as 1 survey respondent suggested, “zero tolerance” should be the rule.

Our study has important limitations. First, perceptions by associate deans may not correspond to the actual environments in their schools. Some deans may have overestimated caring attitudes at their schools. Comparisons of the perspectives of faculty and other healthcare professionals, residents, students, and patients of affiliated hospitals would provide a more contextualized view of caring attitudes. Second, we had a modest response rate, inadvertently omitted 8 schools from our sample, and may have oversampled a subset of the institutions that received more than 1 survey. Our results, therefore, may not generalize to every North American medical school.

In conclusion, survey respondents were pessimistic about their ability to address systemic issues that currently undermine humanistic values and caring attitudes, at the same time, recognizing that the stakes are high if they fail to do so. Patients’ perceptions of the quality of physician–patient interactions, especially in interpersonal treatment and communication are already a concern.37–39 Scholarship on the hidden curriculum has made it clear that, as students and residents are treated in their educational milieu, so do they treat their patients in clinical care. Hopes for achieving a better balance between technical excellence and caring attitudes rest upon efforts to support systems that nurture both in our learners.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Lown, Dr. Chou, Dr. Clark, Dr. Haidet, Dr. White, Dr. Krupat, and Dr. Weissmann of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare received honoraria from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations for their participation in this work. Dr. White is employed by Healthcare Quality and Communication Improvement, LLC. The authors report no conflict of interest. We wish to acknowledge the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations for their vision and support. The opinions contained herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare, the Association of American Medical Colleges, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, or the home institutions of the authors.

Funding for this study was provided by the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

APPENDIX A

Caring attitudes survey instrument

- Please indicate your title within your institution.

- Dean

- Associate Dean of Medical Education and/or Curricular Affairs

- Other

Please indicate if your medical school is a public or private institution.

- Please check the region of the country in which your school is located.

- Northeast

- Midwest

- South

- West

- Please indicate the approximate size of the class of 2009.

- <100

- 101–150

- >150

Response options for questions 5–11: strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree

If students do not come to school with caring attitudes, it is difficult to teach these.

Caring attitudes are emphasized strongly during the preclerkship years at this school.

Caring attitudes are emphasized strongly during the clerkship years at this school.

Caring attitudes are emphasized at least as much as learning scientific knowledge at this school.

Students are strongly encouraged to engage in collaborative learning at this school.

The vast majority of students at this school consistently demonstrate caring attitudes by the time they graduate.

Faculty development programs at this school strongly emphasize the recognition and teaching of caring attitudes.

Response options for questions 12–19: yes, no, don’t know

Does your school ask interviewers to assess caring attitudes in medical school applicants?

If yes, does your school formally train interviewers how to assess these attitudes?

Does your school have a program or resource (such as a dean, formal wellness program, or ombudsperson) that encourages and assists students who wish to examine conflicts between their professional and personal responsibilities?

Does your school require students to participate in a course during which they learn collaboratively with other health science students (e.g., nurses, social workers, and others)?

Does your school give annual awards to the faculty based on caring and humanism?

Does your school require community service of all students as part of their medical school experience?

Does your school have guidelines to ensure that women and underrepresented minorities receive salaries equivalent to others with similar qualifications, academic rank and hours?

Has your school defined competency requirements for the demonstration of caring attitudes?

- Many methods can be used to teach and foster caring attitudes. Please check the 3 predominant methods your school uses to teach caring attitudes during the preclerkship years, and 3 during the clerkship years.

- Didactic sessions

- Problem or case-based learning (PBL)

- Small group discussions (other than PBL, e.g., personal awareness or mindfulness)

- Team learning

- Role modeling

- Mentoring

- Skills training, or feedback on directly observed skills

- Electronic (web or CD-ROM) based teaching

- Other

Response options for questions 21–22: virtually all, most, some, very few

How many students have an ongoing formal mentoring relationship with a faculty member at your school?

- For each of the following groups at your school, how many consistently model caring attitudes toward students?

- Pre-clerkship faculty

- Clerkship faculty

- Research faculty

- House staff

- Of the following potential barriers to teaching or enhancing students’ caring attitudes, please check the 3 that are most significant at your school:

- Paucity of faculty role models

- Lack of designated time in the curriculum

- Time pressures on faculty, increasing demands for productivity

- Lack of faculty development and expertise in teaching in this domain

- Faculty don’t perceive this as important

- Students don’t perceive this as important

- Faculty believe current teaching of this is adequate

- The general learning climate on clerkship rotations is hostile to caring attitudes

- The leadership of the medical school does not feel this is a high priority

- Of the following methods of assessing students’ caring attitudes, please check the 3 predominant methods used at your school.

- Students’ case presentations

- Direct faculty observations of students’ interactions with each other

- Direct faculty observation of students’ interactions with patients and families

- Students’ peer review of observations of each other

- Reports from house staff.

- Direct faculty observation of students’ interactions with the healthcare team (nurses, ward staff, others)

- Patients’ and families’ comments

- Standardized patient assessment exercises or objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE)

- Observations or comments by nurses and other allied health professionals

- Other

- In your school’s clinical skills examinations, what percent of the students’ grade is dependent on interpersonal and communication skills?

- 0

- 1–20%

- 21–40%

- >40%

- We don’t have a clinical skills examination

- Do not know

- For the items below, please check each domain in which your medical school has provided formal faculty development programs within the past year.

- General teaching skills

- Communication skills

- Cultural sensitivity and communication

- Giving and receiving feedback

- Facilitating caring attitudes in students

- Teaching professionalism

- Group facilitation skills

- Mentoring skills

- Facilitating self-reflection and personal awareness

- Physician wellness

Question 27 allowed a free text response

Critics of medical education assert that students often fail to master the interpersonal and communication skills that allow them to display caring attitudes, and that a “hidden curriculum” in medical training hampers further development of, or actually diminishes caring attitudes. Please comment on the active steps your school now takes to ensure that students master advanced relationship-building skills, and steps taken to address the negative effects of the “hidden curriculum” at your school.

Footnotes

Findings contained in this report were presented in part at the 2006 Research and Teaching Forum of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare, Atlanta, Georgia, and the 2006 meeting of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Seattle, Washington.

References

- 1.Bell J, Hays I, Emerson G, et al. Code of medical ethics of the American Medical Association. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/upload/mm/369/1847code.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2006.

- 2.Stewart MA. Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE Jr. Expanding patient involvement in care: effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–528. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.DiMatteo MR. Enhancing patient adherence to medical recommendations. JAMA. 1994;271:79–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Fiscella K, Meldrum S, Franks P, Sheilds CG, Duberstein P, McDaniel SH, Epstein RM. Patient trust: is it related to patient-centered behavior of primary care physicians? Med Care. 2004:42:1049–1055. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Safran DG, Montgomery JE, Chang H. Murphy J, Rogers WH. Switching doctors: predictors of voluntary disenrollment from a primary physician’s practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:130–136. [PubMed]

- 7.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mulloly JP, Dull V, Frankel RM. Physician–patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553–559. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The doctor–patient relationship and malpractice: lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1365–1370. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Epstein RM, Franks P, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Miller KN, Campbell TL, Fiscella K. Patient-centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.ABIM Foundation, ACP–ASIM Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2001;136:243–246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Cuff PA, Vanselow NA (eds). Improving medical education: enhancing the behavioral and social science content of medical school curricula. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press: 2004. [PubMed]

- 12.Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education. Medical Outcome Project. Available at http://www.acgme.org. Accessed December 26, 2006.

- 13.Coulehan J, Williams PC. Vanquishing virtue: the impact of medical education. Acad Med. 2001;76:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Christakis NA. Do clinical clerks suffer ethical erosion? Students’ perceptions of their ethical environment and personal development. Acad Med. 1994;69:670–679. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73:403–407. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hundert EM, Hafferty F, Christakis D. Characteristics of the informal curriculum and trainees’ ethical choices. Acad Med. 1996;71:624–642. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Haidet P, Kelly PA, Chou CL, et al. Characterizing the patient-centeredness of hidden curricula in medical schools: development and validation of a new measure. Acad Med. 2005;80:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Haidet P, Stein HF. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians: the hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S16–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine: 1967.

- 20.Makoul G. Report III: contemporary issues in medicine: communication in medicine. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges: 1999.

- 21.Novack DH, Volk G, Drossman DA, Lipkin M Jr. Medical interviewing and interpersonal skills teaching in US medical schools: progress, problems, and promise. JAMA. 1993;269:2101–2105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Papadakis MA, Teherani A, Banach MA, Knettler TR, Rattner SL, et al. Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in medical school. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2673–2682. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Reiter HI, Eva KW. Reflecting the relative values of community, faculty, and students in the admissions tools of medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire; 2003, 2004, 2005.

- 25.Stern DT, Papadakis M. The developing physician—becoming a professional. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1794–1799. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Stern DT. In search of the informal curriculum: when and where professional values are taught. Acad Med. 1998;73:Suppl 10:S28–S30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Wass V, Van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, Jones R. Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet. 2001;357:945–949. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Ram P, Grol R, Rethans JJ, Schouten B, van der Vleuten CPM, Kester A. Assessment of general practitioners by video observation of communicative and medical performance in daily practice: issues of validity, reliability and feasibility. Med Educ. 1999;33:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Street RL Jr. Methodological considerations when assessing communication skills. Med Encounter. 1997;13:3–7.

- 30.Novack DH, Suchman AL, Clark W, Epstein RM, Najberg E, Kaplan C. Calibrating the physician: personal awareness and effective patient care. JAMA. 1997;278:502–509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Benbassat J, Baumai R. Enhancing self-awareness in medical students: an overview of teaching approaches. Acad Med. 2005;80:156–161. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Smith RC, Dwamena FC, Fortin AH, VI. Teaching personal awareness. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Schindler BA, Novack DH, Cohen DG, Yager J, Wang D, et al. The impact of the changing health care environment on the health and well-being of faculty at four medical schools. Acad Med. 2006;81:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, Weissman P, Gracey CF, et al. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286:1067–1074. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Weissman PF, Branch WT, Gracey CF, Haidet P, Frankel RM. Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts. Acad Med. 2006;81:661–667. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Souba WW, Day DV. Leadership values in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2006;81:20–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Montgomery JE, Irish JT, Wilson IB, Chang H, Li AC, et al. Primary care experiences of Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–2000. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:991–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Murphy J, Chang H, Montgomery JE, Rogers WH, Safran DG. The quality of physician-patient relationships: patients’ experiences 1996–1999. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:123–129. [PubMed]

- 39.Safran DG. Defining the future of primary care: what can we learn from patients? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:248–255. [DOI] [PubMed]