Abstract

Background

An Emergency Department (ED) visit represents a time of significant risk for an older adult; however, little is known about adverse outcomes after an ED visit in the VA system.

Objectives

1) To describe the frequency and type of adverse health outcomes among older veterans discharged from the ED, and 2) To determine risk factors associated with adverse outcomes.

Design

Retrospective, cohort study at an academically affiliated VA medical center.

Patients

A total of 942 veterans ≥ 65 years old discharged from the ED.

Measurements and Main Results

Primary dependent variable was adverse outcome, defined as a repeat VA ED visit, hospitalization, and/or death within 90 days. Overall, 320 (34.0%) patients experienced an adverse outcome: 245 (26%) returned to the VA ED but were not admitted, 125 (13.3%) were hospitalized, and 23 (2.4%) died. In adjusted analyses, higher score on the Charlson Comorbidity Index (hazard ratio [HR] 1.11; 95% CI 1.03, 1.21), ED visit within the previous 6 months (HR 1.64; 95% CI 1.30, 2.06), hospitalization within the previous 6 months (HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.30, 2.22), and triage to the emergency unit (compared to urgent care clinic) (HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.32, 2.36) were independently associated with higher risk of adverse outcomes.

Conclusion

More than 1 in 3 older veterans discharged from the ED experienced a significant adverse outcome within 90 days of ED discharge. Identifying veterans at greatest risk for adverse outcomes after ED discharge can inform the design and targeting of interventions to reduce morbidity and costs in this group.

KEY WORDS: health outcomes, emergency department, elderly, quality of care

INTRODUCTION

Emergency Department (ED) use by older adults has risen steadily and dramatically over the past decade.1 By some estimates, older patients will account for 1 in 4 of all ED visits in the US by 2030.2 The emergency care of older adults is time- and resource-intensive and frequently complicated by underlying chronic medical conditions and unmet social and physical needs.2 However, despite the complexities of their care, between one-half and two-thirds of older patients are discharged from the ED after a diagnosis and treatment plan have been formulated.3

Older adults who are discharged from the ED may be at risk for poor outcomes as a result of high burden of illness, complicated medical conditions, and fragmented care.4,5 Recent studies from the United States, Canada, and Australia have reported that many of these patients endure repeat ED visits or hospitalizations, or both, in subsequent months.6–8 An important venue in which to study older patients discharged from the ED is the Veterans’ Administration (VA), the largest integrated health care system in the United States. The VA provides ED services for 1.7 million patient encounters each year.9 Older adults who utilize the VA health system are more likely than the general population to report poor physical and mental health and have more chronic health conditions.10,11 Whereas this suggests that older veterans may be disproportionately at risk after an ED visit, veterans’ access to VA primary care may mitigate against worse outcomes. Therefore, we sought to investigate these issues by: (1) describing the frequency and type of adverse health outcomes among older veterans discharged from the ED, and (2) determining risk factors associated with adverse outcomes in this population.

METHODS

Design and Sample

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to examine the incidence of and risk factors for adverse outcomes in older veterans discharged from the ED of the Durham VA Medical Center (VAMC), a 274-bed tertiary care referral, teaching, and research facility. During the study period, the Durham VAMC ED consisted of an emergency unit and an urgent care clinic (UCC), each staffed by a separate group of nurses and Internal Medicine residents and attending physicians. All patients were assessed by a triage nurse on arrival. Patients with more acute presenting problems were evaluated in the emergency unit; others were seen in the UCC. This VAMC ED does not accept level 1 trauma patients being transported by Emergency Medical Services (EMS); however, other patients brought in by EMS undergo a similar nurse triage process. Patients were included in the sample if they were: 1) discharged home from the Durham VAMC ED between July 1 and September 30, 2003, 2) ≥65 years, and 3) followed in VA primary care. Because patients without a VA primary care provider (PCP) often visit the ED for medication refills, the last criterion was intended to exclude visits that were not associated with an acute illness or injury. Patients who were admitted to the hospital and those without complete data were excluded. Institutional review boards of Duke University Medical Center and the Durham VAMC approved this study.

Measurements

Dependent Variables

The primary dependent variable was adverse outcome, defined as a repeat VA ED visit, hospitalization, and/or death within 90 days of discharge from the index ED visit. In pilot data collected before initiation of this study, it was determined that the mean time from ED discharge to first follow-up visit with PCP was 77 days. To capture this time frame adequately and be commensurate with other outcome data in the literature, 90 days was chosen for the primary outcome measure. Secondary dependent variables were adverse outcomes within 30 and 180 days postdischarge. Data on repeat VA ED visits were collected locally by electronic query of the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). Hospitalization data were identified using the national VA Patient Treatment File. To avoid over-counting events, a hospitalization preceded by an ED visit (within 24 hours) was considered a hospitalization only. Dates of death were determined by searching the Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem, which captures deaths in or out of the hospital and is approximately 95% complete.12

Independent Variables

Demographic variables included age, race, and sex. ED visit characteristics included the day of visit (weekday versus weekend), time of visit (day versus evening/night) and triage location (emergency unit versus UCC). Health status variables included number of current medications, comorbidities, VA ED visits, and hospital admissions within the previous 6 months (none versus any). CPRS was electronically queried for demographic variables and ED diagnostic information (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] codes).13 To assess medical comorbidity, the patient’s active problem list, most recent primary care visit note, and hospital discharge summaries within the previous year were reviewed to identify specific diagnoses, which were then used to calculate a Charlson Comorbidity Index.14 The Charlson index is a validated method of classifying comorbidity using medical record data that has been used extensively for risk-adjustment and predicting mortality.14,15

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all independent and dependent variables. Independent variables were then entered into Cox proportional-hazards regression models. The risk of adverse events associated with each independent variable is expressed as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The primary analysis considered events within 90 days; similar models were constructed using events within 30 and 180 days. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS® software, version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sample and ED Visit Characteristics

Over a 3-month period, 1,609 patients ≥65 were evaluated in the Durham VAMC ED. After patients admitted to the hospital at the index ED visit (n = 232), not followed in VA primary care (n = 394), and those with incomplete data (n = 41) were excluded, 942 subjects remained in the cohort. Sample and ED visit characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and Visit Characteristics for Older Veterans Discharged from the ED, N = 942

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |

| Age, mean, SD | 74.7 (6.2) |

| Age | |

| 65–69 | 229 (24.3) |

| 70–74 | 238 (25.3) |

| 75–79 | 256 (27.2) |

| ≥80 | 219 (23.3) |

| Male | 927 (98.4) |

| Current medications, mean (SD) | 6.1 (5.5) |

| Current medications | |

| 0 | 227 (24.1) |

| 1–4 | 173 (18.4) |

| 5–8 | 257 (27.3) |

| 9 or more | 285 (30.2) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |

| 0 | 501 (53.2) |

| 1–2 | 340 (36.1) |

| 3 or greater | 101 (10.7) |

| ED visit within previous 6 months | |

| 0 | 639 (67.8) |

| 1 | 167 (17.7) |

| 2 | 72 (7.6) |

| ≥3 | 64 (6.8) |

| Hospitalization within previous 6 months | |

| 0 | 804 (85.4) |

| 1 | 103 (10.9) |

| 2 or more | 35 (3.7) |

| Index ED Visit Characteristics | |

| Day of visit | |

| Weekday | 819 (86.9) |

| Weekend | 123 (13.1) |

| Time of visit | |

| Day 7a–6p | 831 (88.2) |

| Evening/night 6:01p–6:59a | 111 (11.8) |

| Triage location | |

| Emergency Unit | 273 (29.0) |

| Urgent Care Clinic | 669 (71.0) |

| Discharge diagnosis category* | |

| Ill-defined signs or symptoms | 160 (19.4) |

| Musculoskeletal conditions | 131 (15.9) |

| Circulatory system conditions | 99 (12.0) |

| Respiratory conditions | 79 (9.6) |

| Endocrine/metabolic disorders | 58 (7.0) |

| Prescribed a new medication at ED discharge | 421 (44.6) |

*Grouped by ICD-9 codes. Data shown for 5 most common categories.

Frequency and Type of Adverse Health Outcomes

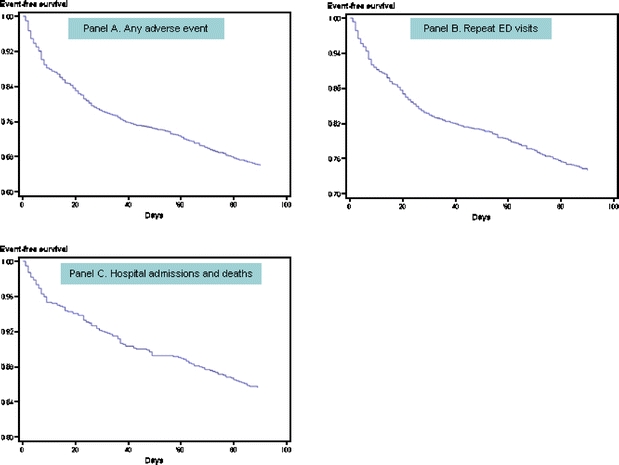

A total of 320 patients (34.0%) discharged from the ED experienced 1 or more adverse outcomes within 90 days of the index visit; 26% returned to the VA ED but were not admitted, 13.3% were hospitalized, and 2.4% died. Sixty percent of the repeat VA ED visits and 57% of the hospitalizations occurred within the first 30 days (Fig. 1). Within 180 days after the index ED visit, 44.5% of patients had made a repeat visit to the ED (n = 316), been hospitalized (n = 186), or died (n = 42). The overall adverse event rate was higher in patients triaged to the emergency unit (46.2%) and those who had a recent previous ED visit (45.9%) or recent hospitalization (55.1%).

Figure 1.

Time to first adverse event (repeat ED visit, hospitalization or death) following ED discharge.

Risk Factors Associated with Adverse Outcomes

Of the 20 most common ED discharge diagnoses, the adverse event rate was lowest among patients diagnosed with joint disorders (4 of 31, 12.9%), osteoarthritis (3 of 21, 14.3%), cellulitis (3 of 13, 23.1%), and back disorders (9 of 38, 23.7%). Patients with heart failure (8 of 10, 80%), bronchitis (6 of 10, 60%), fluid or electrolyte disorders (6 of 11, 54.4%), and gout (8 of 16, 50%) were most likely to have an adverse outcome.

In adjusted analyses, factors associated with increased risk included higher score on the Charlson Comorbidity Index, ED visit within the previous 6 months, hospitalization within the previous 6 months, and triage to the emergency unit (compared to UCC). Weekend and evening or night visits were not associated with adverse outcomes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk Factors for Adverse Events Within 90 After ED Discharge, N = 942

| Risk factor | Patients Without Adverse Outcome, n = 622 | Patients With Adverse Outcome, n = 320 | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 74.9 (6.3) | 74.4 (6.0) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) |

| Male, n (%) | 613 (98.6) | 314 (98.1) | 0.73 (0.33, 1.66) |

| Weekend visit, n (%) | 72 (11.6) | 51 (15.9) | 1.38 (0.95, 1.98) |

| Evening/night visit, n (%) | 69 (11.1) | 42 (13.1) | 1.15 (0.81, 1.64) |

| Triage location ED, n (%) | 147 (23.6) | 126 (39.4) | 1.76* (1.32, 2.36) |

| Number of current medications, mean (SD) | 5.5 (5.1) | 7.3 (6.0) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.04) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.11* (1.03, 1.21) |

| ED visit within previous 6 months, n (%) | 62 (10.0) | 76 (23.8) | 1.64* (1.30, 2.06) |

| Hospitalization within previous 6 months, n (%) | 164 (26.4) | 139 (43.4) | 1.70* (1.30, 2.22) |

*P < .05

Multivariable analyses performed using the 30- and 180-day time horizons yielded similar results. In the model using events within 30 days, Charlson score was not significant, (1.06, 95% CI 0.95, 1.18) but emergency unit triage, (1.63, 95% CI 1.12, 2.39), previous ED visits (1.72, 95% CI 1.28, 2.31), and previous hospitalizations (1.51, 95% CI 1.06, 2.15) were independently associated with increased risk. In the model using 180 days, Charlson score (1.12, 95% CI 1.05, 1.21), emergency unit triage (1.65, 95% CI 1.28, 2.14), previous ED visits (1.62, 95% CI 1.33, 1.98), previous hospitalizations (1.58, 95% CI 1.24, 2.01), and higher number of medications (1.02, 95% CI 1.00, 1.04) were all associated with increased risk of adverse events.

DISCUSSION

More than 1 in 3 older veterans experienced an adverse outcome within 90 days of being discharged from the ED. The risk was particularly high among those with recent health service use, greater comorbidity, and more acute presenting problems. These findings extend previous work by documenting the frequency of adverse events in a geographic region and health care system that have not been previously studied.

The rates of repeat health service use and mortality observed in this study are consistent with those reported in other settings (Table 3).6,7 Despite the fact that all of the patients in this study had PCPs, nearly 1 of 4 returned to the VA ED within 90 days. Most repeat visits to the ED occurred within the first 30 days after discharge, a finding also supported by previous work.8,16 The observed subsequent hospital admission rates are also in accordance with other reports in the literature.6,7,17,18 Among veterans triaged to the higher level of care at their index ED visit, nearly 1 of 5 were admitted to the hospital within 90 days. Similar hospital admission rates (23%) have been reported in chronically ill veterans after discharge from an inpatient hospital stay.19

Table 3.

Repeat ED Visits and Hospitalizations After ED Discharge in Different Health Systems Since 1990*

| Location and Year | Setting | No. Patients | Repeat ED Use (%) | Hospitalization (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days post ED Discharge | Days Post ED Discharge | |||||||

| 30 | 90 | 180 | 30 | 90 | 180 | |||

| North Carolina, USA 2003 | Veterans’ Affairs (VA) ED | 942 | 15.3 | 26 | 33.5 | 7.5 | 13.3 | 19.7 |

| Ohio, USA 1999/2000 | 2 urban, academic EDs | 647 | 18 | – | 38† | 14 | – | 27† |

| Quebec, Canada 1996 | 4 urban, university-affiliated hospital EDs | 1,122 | 19.3 | 24 | 43.9 | – | – | 25 |

| Illinois, USA 1995/1996 | Academic, urban ED | 463 | 12 | 19 | – | 7.6 | 16 | – |

| New South Wales, Australia 1994/1995 | University ED | 468 | – | – | – | 17.1 | – | – |

*Reported in cohort studies performed since 1990 that evaluated repeat ED visits or hospitalizations at 30 or more days after discharge from index ED visit

† Outcome measured at 120 days

– = not reported

Among the risk factors for adverse outcomes identified in this study, prior health service use7,17 and greater medical comorbidity (measured by higher Charlson score7 and higher numbers of medications)17 are supported by other reports in the literature. Another notable finding in this study was that acuity of presenting illness was an independent risk factor for subsequent health service use and death. From a clinical standpoint, this is not surprising. However, few studies have attempted to incorporate acuity of presenting illness into risk assessment for future adverse outcomes. One study found that ambulance arrival at the index ED visit conferred higher risk of poor outcomes. The authors noted that this may be a marker for more severe illness, a patient’s propensity to use the emergency care system or dependence in transportation.7 At least 2 studies used discharge diagnosis categories to predict adverse outcomes. One reported that patients with digestive diagnoses were more likely to return to the ED,8 and the other found no association between discharge diagnosis and risk of subsequent hospital admission.6 The data in this study suggest that patients with musculoskeletal conditions may be at lower risk of adverse outcomes, but limited numbers of patients in each diagnostic category preclude definite conclusions.

This study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single VAMC over a 3-month period; therefore, local practice patterns and seasonal variation could have affected results. Second, repeat ED visits were only measured at the Durham VAMC; therefore, the ED return rate may be higher than reported if veterans are also seeking care in other VA and non-VA facilities. However, previous studies have shown that veterans enrolled in primary care receive the vast majority of their care at their home VAMC.20 Third, these data do not provide information about whether return visits or hospitalizations were for the same diagnosis as the index ED visit and this is an important topic for future study. Fourth, we did not have access to data on functional status and whether patients had attempted to contact their PCPs before or after an ED visit. However, the risk factors identified in this study are important because they can be readily obtained from the patient’s medical record and therefore could be adapted for use on a large scale within a system with electronic health records such as VA. Finally, the predominantly male population is not representative of the geriatric population as a whole, and results must be interpreted accordingly.

Some authors have suggested that an ED visit is a “sentinel event” in the life of an older adult,21 and, indeed, evidence is accumulating to support this view. These data demonstrate that older veterans discharged from VA EDs face a serious risk of adverse events within the subsequent 90 days. Identifying veterans at greatest risk for adverse outcomes after ED discharge can inform the design and targeting of interventions to reduce morbidity and costs in this group.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the following: Duke Aging Center’s John A. Hartford Center of Excellence grant #2002-0269, NIA ID K24-AI-51324-01 and Durham Veterans’ Affairs (VA) Medical Center Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC) and Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care. This research was conducted while Dr. Hastings was supported by a Hartford Geriatrics Health Outcomes Scholar Award from the AGS Foundation for Health in Aging/John A. Hartford Foundation, the VA Special Fellowship in Advanced Geriatrics, and the Duke Aging Center’s John A. Hartford Center of Excellence grant #2006-0109. Dr. Weinberger was supported as a VA HSR&D Career Scientist. The authors also thank Carl Pieper, Dr PH, for statistical advice, Aisha McGriff, BS and Linda Folsom, RN for assistance with data collection, and Karen M. Stechuchak, MS for assistance with VA administrative data files.

Conflicts of interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Cunningham P, May J. Insured Americans drive surge in emergency department visits. Issue Brief #70. October 2003. Center for Studying Health System Change. http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/613/613.pdf. [PubMed]

- 2.Wilber ST, Gerson LW, Terrell KM, et al. Geriatric emergency medicine and the 2006 Institute of Medicine Reports from the Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the US Health System. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1345–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB. Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:238–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mion L, Odegard PS, Resnick B, et al. Interdisciplinary care for older adults with complex needs: American Geriatrics Society position statement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):849–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Caplan GA, Brown A, Croker WD, Doolan J. Risk of admission within 4 weeks of discharge of elderly patients from the emergency department—the DEED study. Discharge of elderly from emergency department. Age Ageing. 1998;27:697–702. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Friedmann PD, Jin L, Karrison TG, et al. Early revisit, hospitalization, or death among older persons discharged from the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19(2):125–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.McCusker J, Cardin S, Bellavance F, Belzile E. Return to the emergency department among elders: patterns and predictors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:249–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Greiner GT, Jesse R, Sales AE. The State of Emergency Medicine in VHA: Results of the 2003 VHA Emergency Department Survey. Abstract No. 3071. VA HSRD National Meeting 2005.

- 10.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of Veterans Affairs: results from the Veterans Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):62632. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Agha Z, Lofgren RP, Van Ruiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs Medical Centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):32527. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, et al. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:462–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, 4th Ed. Los Angeles: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1992.

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method for classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies. Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.D’Hoore W, Bouckaert A, Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson Comorbidity Index with administrative data bases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1429–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.McCusker J, Healey E, Bellavance F, Connolly B. Predictors of repeat emergency department visits by elders. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(6):581–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Meldon SW, Mion LM, Palmer RM, et al. A brief risk-stratification tool to predict repeat emergency department visits and hospitalizations in older patients discharged from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:224–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, Belzile E, Verdon J. The prediction of hospital utilization among elderly patients during the 6 months after an ED visit. Ann Emerg Med. 2000:36:438–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Smith DM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Weinberger M, et al. Predicting non-elective hospital admissions: a multi-site study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000:53;1113–18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson W, for the VA Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmissions. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1441–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Sanders AB. The older person and the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:880–2. [DOI] [PubMed]