Abstract

The constellation of chronic cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis can include a broad range of differential diagnoses. Although uncommon, exogenous lipoid pneumonia (ELP) should be considered when patients present with this symptom complex. We report a case of a 72-year-old female who presented with hemoptysis, cough, and dyspnea. The admission computed tomography scan of the chest revealed progressive interstitial infiltrates. Bronchoscopy revealed diffuse erythema without bleeding. Culture and cytology of lavage fluid were negative. Open-lung biopsy revealed numerous lipid-laden macrophages and multinucleated foreign-body giant cells. On further questioning, the patient admitted to the daily use of mineral oil for constipation. The diagnosis of ELP was made. The literature review revealed that many cases typically present with chronic cough with or without dyspnea. Our case illustrates an unusual presenting symptom of hemoptysis and the need to identify patients who can be at risk of developing this rare condition.

KEY WORDS: exogenous lipoid pneumonia, mineral oil, laxative

INTRODUCTION

Exogenous lipoid pneumonia (ELP) is a rare form of pneumonia caused by inhalation or aspiration of a fatty substance. ELP has been reported with inhalation or ingestion of petroleum jelly, mineral oils, “nasal drops,” and even intravenous injection of olive oil.1–10 Although it is an unusual cause of chronic lung disease, it is an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of several pulmonary syndromes because progression appears to be halted, or at least slowed, by stopping exposure to the offending lipid substance.

The literature review of this topic revealed that many cases typically present with chronic cough with or without dyspnea. Our case illustrates a rare finding of hemoptysis in a patient with exogenous lipoid pneumonia, who was taking mineral oil nightly. The case also highlights the need for warning labels to be placed on over the counter mineral oil and the need to educate primary care physicians about this possible adverse reaction to this type of laxative, especially in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease or with difficulty swallowing.

CASE

A 72-year-old white female with a past medical history of asthma was admitted to the hospital with a 2- to 3-day history of hemoptysis, cough, and worsening shortness of breath. On her emergency department physical examination, she was dyspneic and coughed up blood-tinged sputum. Vital signs revealed mild hypoxia 88% on room air and tachypnea with a respiratory rate of 34. Her physical exam revealed fine crackles throughout her lung fields but was otherwise unremarkable. She had been admitted 18 months earlier with similar symptoms. At that time, a chest computed tomography (CT) showed diffuse interstitial infiltrates (Fig. 1). She was diagnosed with viral interstitial pneumonia and was discharged with supplemental oxygen in light of her persistent dyspnea and hypoxia. She continued to have daily cough until her current admission, which she attributed to her history of asthma. On the morning of admission, she had hemoptysis, which she estimated at “about a cup.” She also reported intermittent subjective fevers but had not measured her temperature at home.

Figure 1.

Admission chest x-ray demonstrating interstitial infiltrates

Her past medical history was significant for asthma since childhood and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Previous pulmonary function testing had demonstrated moderate obstructive lung disease, increased residual volume, and a decreased diffusion capacity. The decreased diffusion capacity had been attributed to distal airway mucous plugging (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected Pulmonary Function Test Results

| Observed | Predicted | Predicted (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selected spirometry results | |||

| Forced vital capacity (FVC) | 2.32 L | 2.59 L | 90 |

| Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) | 1.27 L | 1.97 L | 65 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 55 | 76 | 72 |

| Selected lung volume results | |||

| Inspiratory capacity | 1.49 L | 2.04 L | 73 |

| Total lung capacity | 4.22 L | 4.75 L | 89 |

| Residual volume | 1.97 L | 2.13 L | 92 |

| DLCO corrected for hemoglobin | 6.02 | 19.48 | 31 |

| DLCO uncorrected for hemoglobin | 6.36 | 19.48 | 33 |

These results were interpreted as showing moderate obstructive pulmonary disease and a marked defect in diffusing capacity. There was no improvement with inhaled bronchodilators (data not shown).

DLCO Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and was intubated for airway protection. Broad-spectrum antibiotics and intravenous steroids were administered. CT scan of the chest and chest x-ray revealed progression of the interstitial infiltrates since her previous admission (Fig. 2). The blood tests for inflammatory arthritides and pertinent viral and fungal serologies (herpes, cytomegalovirus, and aspergillus) were within normal limits (see Table 2). Bronchoscopy revealed diffuse erythema without focal bleeding. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was negative for any bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, or viral pathogens. Cytologic study of BAL fluid was negative for malignant cells. An open-lung biopsy was performed; it revealed numerous lipid-laden macrophages and scattered multinucleated foreign-body giant cells within alveolar spaces and in the interstitium associated with mild interstitial chronic inflammation and fibrosis (Fig. 3). Special stains were negative for acid-fast bacilli and fungi.

Figure 2.

Chest CT scan showing interstitial infiltrates in a cobblestoning pattern

Table 2.

Serologic and Rheumatologic Laboratory Studies

| Laboratory studies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Result | Reference range |

| ANA screen | <40 | <40 |

| Anti-Smith | Neg | Neg |

| Anti-SSA | Neg | Neg |

| Anti-SSB | Neg | Neg |

| Rheum factor screen | Neg | Neg |

| Alpha 1 antitrypsin | 154 mg/dL | 100–200 mg/dL |

| Centromere Ab | None detected | None detected |

| P-ANCA titer | <20, negative | <20 |

| Anti-RNP | Neg | Neg |

| SCL 70 Ab | Three units | 0–49 units |

| HSV PCR | Negative | Negative |

| CMV PCR | Negative | Negative |

| Aspergillus antibody | <1:8 | <1:8 |

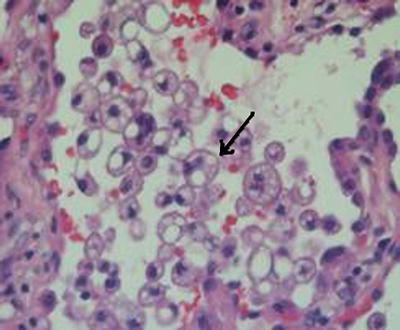

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained slides with both low power (×10) and high power (×40) microscopic view of alveolar and interstitial spaces with lipid-laden macrophages (indicated by arrows)

On further questioning, the patient admitted to taking mineral oil daily for relief of constipation. She also reported frequent heartburn. The diagnosis of ELP was made from her history and the results of open lung biopsy. The lipoid pneumonia was thought to be caused by chronic reflux of mineral oil. The patient was discharged home with instructions to stop using mineral oil. The patient had improvement of her symptoms on outpatient follow-up at 2 and 6 weeks. Patients with chronic cough and hemoptysis should be asked whether they use mineral oil.

DISCUSSION

ELP is a rare cause of chronic cough and hemoptysis. The typical clinical feature of this condition includes a chronic cough with or without dyspnea and the presence of diffuse interstitial infiltrates on imaging studies of the chest. As seen in our case, the diagnosis can be delayed because of rather nonspecific clinical features of the disease and lack of a careful history taking for potential chemical irritants. Physicians need to have a high index of suspicion for ELP when managing patients with chronic cough and hemoptysis and should elicit a history of mineral oil ingestion.

Whereas ELP is thought to be caused by a chronic foreign body reaction to inhaled exogenous lipid droplets, the endogenous lipoid pneumonia is a secondary phenomenon caused by the release of cholesterol and other lipids from tissue breakdown distal to an obstructed airway, the lipid droplets either remain free within the alveoli or are absorbed by alveolar macrophages. Because alveolar macrophages cannot metabolize the fatty substance, the oil is repeatedly released into the alveoli when successive macrophages die.11 Pathologically, ELP is characterized by the presence of giant cell granulomas, alveolar and interstitial fibrosis, and chronic inflammation. Lesions may differ depending on the amount of time the insult has occurred. Biopsy of recent lesions shows alveolar fill-in by lipid-laden macrophages and almost normal alveolar walls and septae.12 Advanced lesions show larger vacuoles and inflammatory infiltrates of alveolar walls, bronchial walls, and septa.12 The oldest lesions on biopsy are characterized by fibrosis and parenchymal destruction around large lipid-containing vacuoles, as seen in our patient.12 Special staining techniques can more effectively demonstrate that the vacuoles are lipid filled.

The symptoms of ELP may be an insidious onset of cough and/or dyspnea, similar to those of other chronic lung diseases. However, other case reports describe a presentation similar to infectious pneumonia with subacute onset of fever, with or without cough. Hemoptysis, as seen in our patient, is unusual, having been reported in only one of the cases we were able to identify in the English language literature. Systemic symptoms are uncommon unless chronic hypoxia precipitates weight loss from chronically increased work of breathing.

Physical exam findings are those of interstitial lung disease. The lungs can be clear or have fine rales. With progressive, longstanding disease, physical findings related to chronic hypoxia can develop. Chest x-ray findings are diverse and can mimic many other diseases including carcinoma, acute or chronic pneumonia, ARDS, or a localized granuloma. CT scan of chest most commonly shows alveolar consolidations of low attenuation values, ground glass opacities with thickening of intralobular septa (crazy paving pattern, Fig. 2), or alveolar nodules, although a variety of appearances have been described.4,13,14 Magnetic resonance imaging may reveal a high signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging consistent with lipid content.12 Similarly, a lower lobe predominance of the radiographic findings is often but not uniformly seen. Positron-emission tomography imaging may be abnormal, suggesting malignancy, if the lipoid pneumonia is complicated by a bacterial infection.17

Diagnosis of ELP is often difficult, as symptoms, signs, and radiographic findings are all quite nonspecific. It is difficult to diagnose clinically, and physicians may not consider this in the differential diagnosis of chronic cough or hemoptysis.12 Patients may not be aware of aspiration of the offending agent as the fatty substance may not stimulate a cough reflex.9 Moreover, patients are typically unaware of the side effects of these substances and may not consider the offending agent as part of their medication regimen. Of note, not all cases of ELP are caused by aspiration; some cases are caused by inhalation and intratesticular absorption. Case reports have revealed that ELP can develop among fire eaters and after olive oil injection into the testes, petroleum application to the face for erythrodermic psoriasis, and compulsive use of lip balm.15 Mineral oil, in particular, besides being a common nonprescription laxative, is used for a variety of disorders. Traditional medical uses for mineral oil among adults range from constipation to tracheostomy care. Particularly in certain cultures, it may be used as a remedy for a variety of other common complaints, including nasal stuffiness and colic among children. Mexican cultures use mineral oil for colic, cough, and other symptoms in infants.1 In Africa and the Middle East, ELP is mostly seen in infants because of the forced feeding with clarified butter.14,18 When the lipid substance is used as a folk remedy, persons may be particularly unlikely to mention it. Most cases are diagnosed only after transbronchial biopsy or open-lung biopsy. Microscopic examination of sputum or BAL material may point to the diagnosis by demonstrating lipid laden macrophages.

The treatment of this disorder is not well-defined, beyond avoiding ongoing exposure and providing supportive care. Systemic steroids have been used to slow the inflammatory response but are supported only by anecdote. Because most cases will resolve spontaneously with cessation of exposure, it seems steroids can be withheld unless the lung injury is severe and ongoing.14 Lung lavage with an emulsifying liquid has been used with good outcomes in a severe case of ELP.11,16

The clinical presentation of our patient is unusual in two aspects. First, the CT scan and chest x-ray showed interstitial pneumonitis instead of the more typical alveolar pattern. Second, hemoptysis is somewhat unusual and when reported, has been scant, in contrast to our patients report of a cup of hemoptysis. In our review of literature, we found a single case report of ELP where a patient presented with massive hemoptysis.9 Conversely, our patient had a number of typical features: she was older, gave a history of GERD, and used mineral oil, the most commonly reported cause of ELP, on a nightly basis. This case illustrates the importance of considering the diagnosis of ELP in the case of recurrent pneumonia or chronic progressive lung disease. There is no single clinical feature that is specific for the condition, so the Internist must have a high index of suspicion to consider this diagnosis in patients presenting with undiagnosed chronic cough, dyspnea, or recurrent pulmonary infiltrates on routine imaging studies. ELP should be in the differential diagnosis in a patient with a chronic cough and hemoptysis.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the Department of Pathology at the University of Kansas for providing the slides on our patient. There was no funding for the writing of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement None Disclosed.

References

- 1.Hoffman LR, Yen E, et al. Lipoid pneumonia due to Mexican folk remedy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:11 (Nov). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Costa, et al. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia—a case report. Rev Port Pneumol. 2005;11(6):567–72 (Nov–Dec). [PubMed]

- 3.Chaveau M., et al. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia: a simple diagnosis? Rev Med Liege. 2005;60(10):799–804 (Oct). [PubMed]

- 4.Gondouin A, Manzoni P, et al. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia: a retrospective multicentre study of 44 cases in France. Eur Respir J 1996;9(7):1463–9 (Jul). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bhagat R, Holmes IH, et al. Self-Injection with olive oil. A cause of lipoid pneumonia. Chest. 1995;107(3):875–6 (Mar). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hirata M, Morita M, Maebou A, Hara H, Yoshimoto T, Hirao F. A case of exogenous lipoid pneumonia probably due to domestic insecticide. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1993;31(10):1317–21 (Oct). [PubMed]

- 7.Alaminos Garcia P, Colodro Ruiz A, Menduina Guillen MJ, Banez Sanchez F, Perez Chica G. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia. Presentation of a new case. An Med Interna. 2005;22(6):283–4 (Jun). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Mydlowski T, Malong P, Wiatr E. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia—case report. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2004;72(5–6):214–6. [PubMed]

- 9.Brown AC, Slocum PC, Putthoff SL, Wallace WE, Foresman BH. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia due to nasal application of petroleum jelly. Chest. 1994;105(3):968–9 (Mar). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Dawson JK, Abernethy VE, Graham DR, Lynch MP. A woman who took cod-liver oil and smoked. Lancet. 1996;347(9018):1804 (Jun 29). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Russo, et al. Case of exogenous lipoid pneumonia: steroid therapy and lung lavage with an emulsifier. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):197–8 (Jan). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Laurent F, Philippe JC, Vergier B, et al. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia: HRST, MR and pathologic findings. Eur Radiol. 1999;9(6):1190–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lee KS, Muller NL, et al. Lipoid pneumonia: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1995;19(1):48–51 (Jan–Feb). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Meltzer E, Guranda L, et al. Lipoid pneumonia : a preventable complication. IMAJ. 2006;8:33–5. [PubMed]

- 15.Cohen M, Galbut B, Kerdel F. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia caused by facial application of petroleum. J Am Acad Dermatology. 2003;49:1128–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Wong CA, Wilsher ML. Treatment of exogenous lipoid pneumonia by whole lung lavage. Aust N Z J Med. 1994;24(6):734–5 (Dec). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Chiang IC, Lin YT, Liu GC, Chiu CC, Tsai MS, Kao EL. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia: serial chest plan roentgenography and high-resolution computerized tomography findings. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2003;19(12):593–8 (Dec). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Bandla HP, Davis SH, Hopkins NE. Lipoid pneumonia: a silent complication of mineral oil aspiration. Pediatrics. 1999;103(2):E19 (Feb). [DOI] [PubMed]