Abstract

Background

Dyspnea caused by pulmonary disease is a common symptom encountered by Internists. The most likely diagnosis of pulmonary nodules in a long-term smoker is lung cancer.

Patient/Participant

We report a case of an elderly male with a 70-pack-year smoking history, presenting with exertional dyspnea for 6 months.

Interventions

Detailed review of history was negative. Examination was normal except for diminished breath sounds in all lung fields. Chest x-ray showed bilateral nodular opacities. Computed tomography of thorax revealed multiple bilateral lung masses. A whole-body positron emission tomography revealed enhancement only of the pulmonary masses. Bronchoalveolar lavage was negative for acid fast bacilli, nocardia, and fungi.

Main Results

Lung biopsy showed findings consistent with amyloidosis. Bone marrow biopsy done to investigate primary amyloidosis showed no clonal plasma cells or amyloid staining, thus suggesting a diagnosis of localized pulmonary amyloidosis. Patient is being managed conservatively with close follow-up for signs of progression.

KEY WORDS: dyspnea, tobacco abuse, pulmonary nodules, amyloidosis

INTRODUCTION

Dyspnea on exertion is a common symptom encountered by Internists. Although the symptom of dyspnea has many etiologies, most patients with dyspnea have pathology based in the pulmonary or cardiovascular system.1 The initial evaluation of a patient with dyspnea, in addition to a detailed history and physical examination, includes basic blood work assessing the blood counts, metabolic function, initial imaging with a chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, and pulse oximetry.

The differential diagnoses of bilateral pulmonary nodules on a chest radiograph are extensive and include infections, tumors—primary or metastatic, connective tissue diseases and congenital malformations. However, the most likely diagnosis of pulmonary nodules in a long-term smoker is lung cancer.2 We report a case of an elderly male with a 70-pack-year smoking history, presenting with exertional dyspnea for approximately 6 months. A detailed history, physical examination, and diagnostic evaluation suggested a diagnosis of localized pulmonary amyloidosis. Amyloidosis is an uncommon disease resulting from the deposition of insoluble protein-based amyloid fibrils in various tissues. Although amyloidosis is rare, with an incidence of 8 patients per million per year, localized pulmonary amyloidosis is even more uncommon with a vague, difficult to recognize clinical presentation and limited treatment options.

CASE REPORT

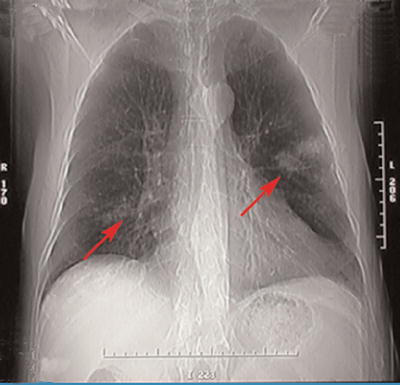

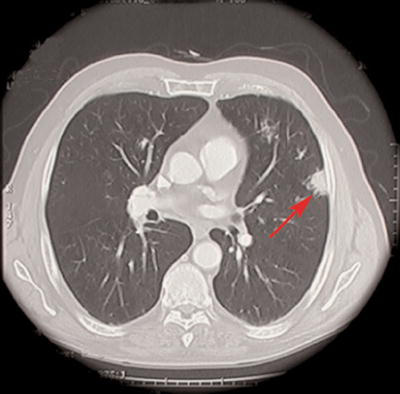

A 73-year-old male with a 70-pack-year smoking history presented with exertional dyspnea for approximately 6 months. It was associated with mild cough and occasional whitish sputum. He did not have a significant past medical or exposure history, and a complete review of systems including history of chest pain, hemoptysis, edema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, urinary symptoms, weight loss, or night sweats was negative. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 98.5°F, pulse rate of 68 beats/min, blood pressure of 160/80 mmHg, respiratory rate of 12/minute with an oxygen saturation of 96% on room air. He did not have any cyanosis, clubbing, or edema. The neck exam revealed no jugular venous distension and the lymphatic system exam did not reveal any lymphadenopathy. Respiratory system exam revealed unlabored breathing, diminished breath sounds with prolonged expiration without any adventitious sounds. Cardiovascular exam revealed a regular rate and rhythm and normal heart sounds without murmurs. Abdominal exam did not reveal any organomegaly. Neurological exam revealed an alert and oriented male with no focal findings and a normal sensory exam. Skin exam was normal and did not reveal any rash, nodules, or ecchymoses. Complete blood count and complete metabolic panel including blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, serum bilirubin, and urinalysis were normal. Chest x-ray showed bilateral ill-defined nodular opacities (Fig. 1). Spiral computed tomography (CT) of the thorax revealed multiple bilateral soft-tissue lung masses (Fig. 2), whereas CT of the abdomen and pelvis was normal. Echocardiography revealed a normal ejection fraction without any myocardial or valvular abnormalities. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody were negative. Whole-body positron emission computerized tomography (PET) revealed 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose enhancement only of the pulmonary masses. As other organs like the liver and kidneys did not enhance on PET scan, further investigation of the enhanced pulmonary masses was undertaken. A broncho-alveolar lavage was performed and was negative for acid fast bacilli, nocardia, and fungi. Transbronchial lung biopsy showed findings consistent with amyloidosis. Congo red and crystal violet stains showed typical amyloid patterns. Thoracoscopic biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of diffuse and nodular amyloid deposition. Patient’s serum protein electrophoresis including immunofixation (SPEP) showed no evidence of monoclonal proteins. Subcutaneous fat or kidney biopsy was not performed. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy done to investigate the possibility of primary amyloidosis showed no evidence of clonal plasma cells, and amyloid staining of bone marrow was negative, thus suggesting a diagnosis of localized pulmonary amyloidosis. Our patient is being managed conservatively and is being followed closely for any signs of progression.

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray showing bilateral ill-defined nodular opacities (arrows)

Figure 2.

Spiral computed tomography of thorax showing soft tissue lung mass (arrow)

DISCUSSION

The American Thoracic Society defines dyspnea as: “a term used to characterize a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that is comprised of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity.”3 Most patients with dyspnea have etiology based in the pulmonary system or cardiovascular system, or both.1 Majority of patients with chronic dyspnea of unclear etiology have 1 of the 4 diagnoses: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, interstitial lung disease, and myocardial dysfunction.4 Evaluation of a patient with dyspnea should include a detailed history and physical examination, complete blood count and metabolic panel, renal function tests, chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, spirometry, and pulse oximetry. Arterial blood gases, measurement of lung volumes, ventilation/perfusion scanning, echocardiography, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing are generally reserved for cases that elude these possible diagnoses on initial evaluation.5

Our patient was found to have multiple pulmonary nodules on the chest radiograph. Given his extensive smoking history, the likelihood of these abnormalities representing metastatic solid organ malignancy was very high.2 Other differential diagnoses to be considered include: multiple abscesses, septic emboli, fungal infection, non-inflammatory conditions like sarcoidosis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, amyloidosis, arteriovenous malformations, pneumoconiosis and inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or Wegner’s granulomatosis6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Causes of Pulmonary Nodules

| Infections | Tumors/Space occupying lesions | Inflammatory | Other causes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis | Benign | Rheumatoid nodule | Arteriovenous malformation |

| Cryptococcosis | Hamartoma | Wegener’s granulomatosis | |

| Blastomycosis | Lipoma | Pulmonary varix | |

| Histoplasmosis | Fibroma | Rounded atelectasis | |

| Coccidiodomycosis | Amyloidoma | Pulmonary infarct | |

| Bacterial Abscess | Lymph nodes | Mucoid impaction | |

| Dirofilariasis | Hematoma | Loculated fluid | |

| Ascariasis | Primary lung Bronchogenic carcinoma | ||

| Echinococcus cyst | Metastatic | ||

| Pneumocystis jiroveci | Breast | ||

| Aspergilloma | Head and neck | ||

| Melanoma | |||

| Colon | |||

| Kidney | |||

| Sarcoma | |||

| Germ cell tumors | |||

| Congenital | |||

| Bronchogenic cyst |

Amyloidosis comprises a group of diseases resulting from the deposition of insoluble protein-based amyloid fibrils in the organs and tissues. Depending on the biochemical nature of the amyloid precursor protein, amyloid fibrils can be deposited locally or may involve any organ in the body. The clinical significance of this deposition may range from none to severe pathophysiologic changes.7 Amyloidosis is uncommon with an incidence of 8 patients per million per year.8 Diagnosis of this disease is difficult owing to its diverse clinical presentation. Amyloidosis can be classified into various types, i.e., primary amyloidosis, which is usually associated with the plasma cell disorders like multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and consists of immunoglobulin light chains (AL); secondary amyloidosis, which is associated with chronic inflammatory diseases and consists of amyloid fibrillary protein (AA). Other types include familial (hereditary) amyloidosis, which consists of abnormal transthyretin protein (ATTR) or lysozyme protein (ALys) produced in the liver and hemodialysis amyloidosis consisting of beta-2-microglobulin, which is normally cleared by the kidney, but cannot be cleared during hemodialysis. Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases can be associated with hormonal proteins of aging such as beta amyloid proteins. The AL and ATTR forms of amyloidosis are usually systemic, but are also observed in localized deposits, for example in skin, lung, and other sites of the body.7

Our patient had localized pulmonary amyloidosis without any signs of systemic involvement, which is relatively rare.9 Gillmore and Harrison categorized respiratory tract amyloidosis as laryngeal, tracheobronchial, parenchymal, and mediastinal or hilar10 (Table 2). Laryngeal amyloidosis may be localized or may be a manifestation of systemic amyloidosis. Deposits commonly occur in the supraglottic larynx and patients generally present with hoarseness or stridor. It is generally benign, but may be progressive.10–12 Tracheobronchial amyloidosis is a rare entity and generally presents with symptoms of airway obstruction like dyspnea or cough.9,13 Occasionally, patients may present with nodules.14 Chest x-ray may not be sensitive and patients may be misdiagnosed as bronchitis or asthma. Thus further investigation with CT scan and bronchoscopy maybe reasonable.15 Irregular airway narrowing, airway wall thickening, or calcified amyloid deposits may be demonstrated on the CT scan.16 Parenchymal pulmonary amyloidosis may be nodular or diffuse. Nodular parenchymal pulmonary amyloidosis is generally asymptomatic and should be differentiated from neoplastic and granulomatous disorders.17 Amyloid nodules are generally localized to the lower lobes in the peripheral and subpleural areas and have smooth contours. Calcification of these nodules may be seen in a few cases.10 Tissue biopsy is essential for the diagnosis. Diffuse parenchymal pulmonary amyloidosis usually presents with dyspnea, cough or hemoptysis, or both. The deposition of the amyloid protein causes alveolar membrane and capillary damage leading to impaired gas exchange causing dyspnea and hemoptysis. Chest x-ray shows diffuse reticular or reticulonodular opacities in the lungs bilaterally.13 The diagnosis is often difficult and confirmed by transbronchial or open lung biopsy. In spite of this, about half of the cases are diagnosed at autopsy.15 Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is rare in localized pulmonary amyloidosis and these patients are generally asymptomatic.10,18–19 Management of localized pulmonary amyloidosis is dependent on the extent of symptoms. For asymptomatic patients, treatment may not be required. Owing to the relative rarity of localized pulmonary amyloidosis, there is lack of randomized controlled trials. Various modalities of treatment reported include bronchoscopic resection, surgical resection, carbon dioxide laser ablation, and Nd:YAG (neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet) laser therapy.20,21 In some cases, low-dose external beam radiation has been tried.22 Parenchymal amyloid nodules generally grow slowly and remain asymptomatic. In such cases, treatment is generally not needed. Surgical resection may be considered; however, there is a possibility of relapse.10

Table 2.

Manifestations of Respiratory Tract Amyloidosis

| Type of manifestation | Clinical implications | |

|---|---|---|

| Laryngeal amyloidosis | Generally localized and benign but may be progressive | |

| Tracheobronchial amyloidosis | Generally presents with obstructive symptoms | |

| Parenchymal amyloidosis | ||

| Nodular | Generally asymptomatic | |

| Diffuse | Usually presents with dyspnea, cough, or hemoptysis | |

| Hilar and mediastinal amyloidosis | Rare in localized form, generally asymptomatic | |

Unlike localized amyloidosis, there have been several controlled trials for systemic amyloidosis. Systemic AL amyloidosis is treated with chemotherapy.23 Various treatment modalities have been studied including melphalan, prednisone, total body irradiation, stem-cell transplantation, vincristine-doxorubicin (adriamycin)-dexamethasone (VAD) regimen, and thalidomide.8 Newer treatment methods for systemic amyloidosis being investigated and presently studied include: Etanercept,24 dendritic cell-based idiotype vaccination,25 NC-531, a sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAGs) mimetic that can inhibit amyloid plaque formation,26 murine antihuman light chain monoclonal antibodies,27 and a competitive inhibitor of serum amyloid P component (SAP) that binds to amyloid fibrils.28 These investigational agents hold promise for the future. Primary amyloidosis and light chain deposition disease have a poor long-term prognosis. The median survival in primary systemic (AL) amyloidosis is less than 18 months,29 but localized pulmonary amyloidosis may have a benign course.9

Our patient was found to have multiple pulmonary nodules on chest radiograph. On detailed investigation including PET scan, SPEP, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, and biopsy from the nodules, other systemic causes were ruled out and the involvement of only pulmonary parenchyma with amyloidosis was substantiated. Thus, the diagnosis of diffuse and nodular parenchymal localized pulmonary amyloidosis was made. The purpose of the extensive work up in our patient was to confirm the diagnosis and rule out systemic involvement as it has management implications. Our patient is being managed conservatively and is being followed closely for any signs of progression.

CONCLUSION

In a smoker with multiple pulmonary nodules, a detailed history, physical exam, common blood tests, and imaging studies supplemented with tissue diagnosis may help in diagnosis and appropriate management of a relatively rare and probably under-recognized condition of localized pulmonary amyloidosis and foster interest in newer diagnostic and treatment modalities.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge S. Enjeti, MD for his assistance with the management of this patient.

Conflict of Interest Neither author has any conflict of interest related to this article.

Disclosure of financial support The manuscript is being resubmitted with corrections and explanation of reviewer comments. It is not being simultaneously submitted elsewhere. The abstract was presented as a poster at the Southern Society of General Internal Medicine in Atlanta in March 2006 and SGIM meeting in Los Angeles in April 2006. There is no financial support from commercial sources for the work reported.

Statement of proprietary interest The authors hereby state that there are no commercial of proprietary interest of any kind of any drug, device, or equipment mentioned in this study. Neither author has any financial interest of this study. This manuscript was prepared solely by the authors listed.

References

- 1.Ingram RH Jr., Braunwald E. Dyspnea and pulmonary edema. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine—16th Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:203.

- 2.Wingo PA, Ries LA, Giovino GA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1996, with a special section on lung cancer and tobacco smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(8):675–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.The American Thoracic Society. Dyspnea. Mechanisms, assessment, and management: a consensus statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:321–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Pratter MR, Curley FJ, Dubois J, Irwin RS. Cause and evaluation of chronic dyspnea in a pulmonary disease clinic. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(10):2277–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Chesnutt MS, Prendergast TJ. Common manifestations of lung disease. In: Tierney LM Jr., McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, et al, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment—45th Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:215.

- 6.Beers MH, Porter RS, Jones TV, et al, eds. Approach to the patient with pulmonary symptoms, In: The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy—18th Ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2006:361.

- 7.Sipe JD, Cohen AS. Amyloidosis. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine—16th Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:2024–5.

- 8.Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Hayman SR. Amyloidosis. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2005;18(4):709–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Utz JP, Swensen SJ, Gertz MA. Pulmonary amyloidosis: the Mayo Clinic experience from 1980–1993. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:407–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis and the respiratory tract. Thorax. 1999;54:444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Kurtin PJ, Kyle RA. Laryngeal amyloidosis: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;106:372–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Talbot AR. Laryngeal amyloidosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:147–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cordier JF, Loire R, Brune J. Amyloidosis of the lower respiratory tract: clinical and pathologic features in a series of 21 patients. Chest. 1986;90:827–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Cotton RE, Jackson JW. Localized tumors of the lung simulating neoplasm. Thorax. 1964;19:97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Xu L, Cai BQ, Zhong X, Zhu YJ. Respiratory manifestations in amyloidosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2005;118(24):2027–33. [PubMed]

- 16.O’Regan A, Fenlon HM, Beamis JF Jr, Steel MP, Skinner M, Berk JL. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis: the Boston University experience from 1984 to 1999. Medicine 2000;79:69–79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Hui AN, Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Wehunt WD. Amyloidosis presenting in the lower respiratory tract; clinicopathologic, radiologic, immunohistochemical, and histochemical studies on 48 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:212–8. [PubMed]

- 18.Thompson PJ, Citron KM. Amyloid and the lower respiratory tract. Thorax. 1983;38:84–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Gallego FG, Canelas JC. Hilar enlargement in amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:531. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Nugent AM, Elliott H, McGuigan JA, Varghese G. Pulmonary amyloidosis: treatment with laser therapy and systemic steroids. Respir Med. 1996;90:433–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Breuer R, Simpson GT, Rubinow A, Skinner M, Cohen AS. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis: treatment by carbon dioxide laser photoresection. Thorax. 1985; 40:870–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Rubinow A, Celli BR, Cohen AS, et al. Localized amyloidosis of the lower respiratory tract. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:603–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kyle R, Gertz M, Greipp P, et al. A trial of three regimes for primary amyloidosis: colchicine alone, melphalan and prednisolone, and melphalan, prednisolone and colchicine. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1202–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Hussein MA, Juturi JV, Rybicki L, Lutton S, Murphy BR, Karam MA. Etanercept therapy in patients with advanced primary amyloidosis. Med Oncol. 2003;20:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Lacy MQ, Wemstein P, Gertz MA, et al. Dendritic cell-based idiotype vaccination for primary systemic amyloidosis and post transplant multiple myeloma Proc Vlll lnt Myeloma Workshop 2001; p 132.

- 26.Geerts H. Nc-531 (Neurochem). Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;5:95–100. [PubMed]

- 27.Solomon A, Weiss DT, Wall JS. Immunotherapy in systemic primary (AL) amyloidosis using amyloid-reactive monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2003;18:853–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Pepys MB, Herbert J, Hutchinson WL, et al. Targeted pharmacological depletion of serum amyloid P component for treatment of human amyloidosis. Nature 2002;4(17):254–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Greipp PR, et al. Long-term survival (10 years or more) in 30 patients with primary amyloidosis. Blood. 1999;93(3):1062–6. [PubMed]