In an urban health care system that is responsible for delivering care to approximately 90,000 adult patients, a typical primary care provider delivers care to a panel of about 2,000 patients1, 2. Among the 300 patients aged 65 years and older in this typical primary care provider panel, 150 of these older adults suffer from at least three chronic conditions, 195 patients report musculoskeletal pain, 93 patients report feeling anxious, and 63 patients are hospitalized every year1–4. Applying relevant management guidelines for each chronic disease that is affecting the average older patient would lead to the prescription of approximately 12 medications with a cost of $400 per patient per month, numerous complex non-pharmacological regimens, and attention to conflicting recommendations and drug interaction across disease-specific guidelines5. In addition to managing acute illnesses, this primary care provider needs an estimated 10 hours per working day to deliver all of the recommended care for patients with chronic conditions and an additional 7 hours per day to provide preventive services6.

Only 24 patients of the entire 2,000 patient panel would have dementia in any given year. Within 6 years, 10 of these patients with dementia would die, and another 10 would require care in a skilled facility due to dementia progression7. Sadly, only 8 patients out of the 24 patients would be recognized by the primary care system as having dementia1, 7, 8. Patients with dementia in the primary care system also suffer from numerous chronic medical conditions, receive multiple prescriptions including psychotropic drugs, display a wide range of behavioral and psychological symptoms, and extensively utilize the health care system2, 4, 8. More than 20% of these patients with dementia are exposed to at least one definitely inappropriate anticholinergic medication and less than 10% are prescribed appropriate pharmacotherapy for their dementing disorder4. Unfortunately, the complicated medical and psychiatric needs of these 24 demented patients affects not only their own care but also the health of their informal caregivers who become vulnerable to suffer from psychological burden, develop depression, use psychotropics and have high mortality rates2, 4, 7, 8.

The current primary care system is facing significant challenges in delivering safe, high quality, and cost-effective services to its patients in accordance with the various disease-specific chronic care and preventive service recommendations. In response to the complex biopsychosocial needs of its older primary care patients, in general, and those with dementia in particular, the system often falls short of excellence1, 4, 9–11. Primary care physicians report having insufficient time to spend with their patients and feel overworked and dissatisfied9–13. Changes in this care environment that continue to place increasing demands on providers are not only difficult, but may be harmful if the complexities of this environment are not taken into account. Thus, the most relevant and important question facing an older patient with dementia (and his or her family members) is: Does my primary care provider have the time, the resources, and the delivery vehicle to care for me?

In this issue of our journal, Hinton et al. 12 sheds more light on the challenges facing the primary care provider in caring for patients with dementia. They interviewed 40 providers from various health care organizations including academic medical centers, managed care, and solo private primary care practices. This excellent qualitative study again demonstrated that the current operational structure of primary care is not prepared to manage the biopsychosocial needs of patients suffering from dementia12. Reported limitations include insufficient provider time, inadequate reimbursement, poor access to dementia care expertise and community resources, lack of adequate communication across the various medical, social and community dementia care providers, and finally, the absence of an interdisciplinary dementia care team12. The results from this study are even more striking when one considers that Hinton et al. focused primarily on the challenges of managing behavioral problems in patients with dementia. It seems likely that similar or additional frustrations would be elicited by interviews focusing on a number of other aspects of caring for patients with dementia, such as the challenges of providing palliative care to this population18.

Dementia is characterized by a complex and prolonged interaction of cognitive, functional, behavioral, and psychological symptoms that decrease the quality of life for both the patient and the caregiver and lead to high health care utilization by both7, 8. Improving the health outcomes of this dyad requires three crucial steps. First, the development of multicomponent pharmacological and psychosocial interventions specific for dementia-related disability; second, the development of accurate outcome assessment methods that match the dosing of these interventions with the patient’s and caregiver’s individualized needs; and third, the development of innovative dementia care delivery processes such as those used in the Collaborative Chronic Care Models13. Notably, these models extend the dementia care setting beyond the primary care office into the homes and communities of patients and their caregivers.

Over the past decade, several research groups have successfully developed and evaluated various comprehensive dementia care programs2, 14–17. These programs offer a flexible and comprehensive framework to modify the primary care delivery systems in accordance with the local resources and demands. The models recognize that communities will vary greatly in the available resources and that these resources will change over time. Moreover, these models emphasize the importance of collaboration and coordination of care across different health care providers, family, and community organizations and agencies.

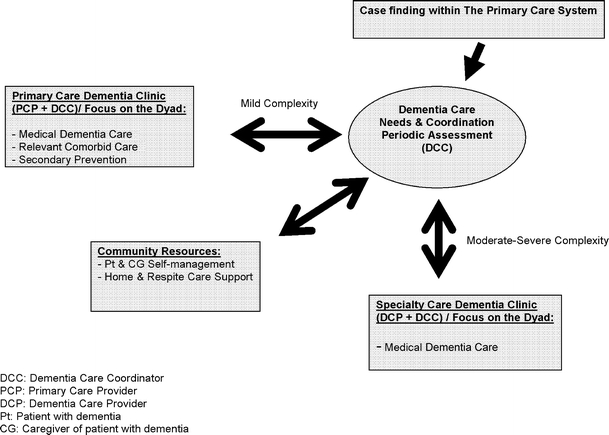

The content of the ideal collaborative dementia care program would include the following (see Fig. 1):

A feasible dementia identification and diagnosis process including a reliable tool for periodic needs assessment and evaluation of ongoing therapy.

Pharmacological and psychosocial interventions that prevent or reduce the family caregiver’s psychological and physical burden.

Self-management tools to enhance the patient and the caregiver skills in managing dementia disability and navigating the health care system.

- Pharmacological interventions for care-recipients that target the cognitive, functional, and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia such as

- Enhancement of the patient’s cholinergic system via prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors and decreasing exposure to medication with anticholinergic activities

- Improvement in medication adherence

- Reduction in cerebrovascular risk factors such hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia

- Prevention and management of delirium, depression, and psychosis superimposed on dementia

Case management and coordination with community resources including adult day care, respite care, and support groups.

Modification of the patient’s physical home environment to accommodate dementia disability.

An increasing focus on palliative care needs as the illness progresses, including advance care planning, attentive management of pain and other symptoms, avoidance of burdensome and undesired medical treatments, and eventual discussion of referral to hospice.

Fig. 1.

The ideal collaborative dementia care program

Delivering the right dose and the right combination of the above critical components of dementia care program to the right dementia patient and the right caregiver at the right time is crucial. The typical primary care practice is not currently prepared to deliver this care. Primary care needs much greater support and integration with community services and access to dementia support teams if primary care is to succeed in caring for the growing population of older adults with dementia. As shown in the figure, finding efficiency and quality in this system will likely require a stepped-care approach where the intensity of specialty care varies according to the level of patient disability. Based on the complexity of the patient and the caregiver needs, the dementia support team could operate in a periodic consultancy model, ongoing co-management mode or as the putative primary care provider (see Fig. 1). For older adults with advanced dementia, we need to begin a dialogue about the limits of primary care approaches. Such a dialogue must include both the strengths of a generalist approach and its weaknesses.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Boustani is supported by NIA Paul B. Beeson K23 Career Development Award # 1-K23-AG026770-01. Dr. Sachs is supported by Alzheimer’s Association grant IIRG-07-60105. Dr. Callahan is supported by NIA awards K24-AG026770-01 and P30AG024967.

References

- 1.Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Inter Med. 2005;20:572–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295:2148–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Sha MC, Callahan CM, Counsell SR, et al. Physical symptoms as a predictor of health care use and mortality among older adults. Am J Med. 2005;118(3):301–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Schubert CC, Boustani M, Callahan CM, et al. Comorbidity profile of dementia patients in primary care: are they sicker? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:104–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ostbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, et al. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):209–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, et al. Screening for Dementia. Systematic Evidence Review. Available at www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD; 2003a.

- 8.Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, et al. Screening for dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003b;138:927–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bodenheimer T. Primary care in the United States. Innovations in primary care in the United States. BMJ. 2003;326(7393):796–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Buttar AB, et al. Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE): a new model of primary care for low-income seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1136–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Tanner CE, Eckstrom E, Desai SS, et al. Uncovering frustrations. A qualitative needs assessment of academic general internists as geriatric care providers and teachers. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):51–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hinton L, Franz CE, Reddy G, et al. Practice constraints, behavioral problems, and dementia care: Primary care physicians’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med 2007 (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2015–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Fox P, Newcomer R, Yordi C, Arnsberger P. Lessons learned from the Medicare Alzheimer Disease Demonstration. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2000;14:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:727–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:713–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1057–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]