Abstract

BACKGROUND

Improving physician health and performance is critical to successfully meet the challenges facing health systems that increasingly emphasize productivity. Assessing long-term efficacy and sustainability of programs aimed at enhancing physician and organizational well-being is imperative.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether data-guided interventions and a systematic improvement process to enhance physician work-life balance and organizational efficacy can improve physician and organizational well-being.

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

From 2000 to 2005, 22–32 physicians regularly completed 3 questionnaires coded for privacy. Results were anonymously reported to physicians and the organization. Data-guided interventions to enhance physician and organizational well-being were built on physician control over the work environment, order in the clinical setting, and clinical meaning.

MEASUREMENTS

Questionnaires included an ACP/ASIM survey on physician satisfaction, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), and the Quality Work Competence (QWC) survey.

RESULTS

Emotional and work-related exhaustion decreased significantly over the study period (MBI, p = 0.002; QWC, p = 0.035). QWC measures of organizational health significantly improved initially and remained acceptable and stable during the rest of the study.

CONCLUSIONS

A data-guided program on physician well-being, using validated instruments and process improvement methods, enhanced physician and organizational well-being. Given the increases in physician burnout, organizations are encouraged to urgently create individual and systems approaches to lessen burnout risk.

KEY WORDS: physician satisfaction, organizational behavior, health care administration

INTRODUCTION

Changes in the health care practice environment have created substantial stressors for physicians. Stressors include time-constrained patient care, lack of resources, decline in compensation, malpractice litigation, and erosion of professional autonomy. They contribute to decreased physician satisfaction1 and problems such as fatigue, anxiety, depression, suicide, substance abuse, cardiovascular disease, disability, and broken relationships.2–13 Many experience burnout as a deterioration of values, dignity, spirit, and will.7,8

Patients and health systems are also harmed. Lower physician job satisfaction correlates with increased medical errors and a deterioration of the doctor–patient relationship.3,14 Losses to physician groups, health systems, and the community are considerable.

Some describe a conspiracy of silence among physicians in responding to colleagues’ distress and in caring for themselves.15,16 Most intervention efforts have focused on individual rather than systems approaches to well-being. As many stressors facing physicians are system-generated, both individual and organizational approaches are needed.17,18 Understandably, JCAHO now requires that hospital medical staffs implement organizational processes to promote physician health and assist physicians suffering from burnout and impairment.19

We describe and evaluate a program on physician and organizational well-being. The program created a common language, culture, and leadership strategy to promote well-being. Our hypothesis was that a senior-management-supported physician well-being program that identifies and addresses individual and organization stressors would improve the well-being of physicians.

METHODS

Setting

Legacy Clinic is a primary care group similar to other established employed physician models in Portland, Oregon, comprised of 6 sites, 32 physicians (25 Internal Medicine and 6 family medicine), and 1 family nurse practitioner. The organization, part of the Legacy Health System, was founded in 1999 after a multispecialty group dissolved. The clinicians were weary after the turmoil of their practice change. The administration, aware of the physician distress, aimed to improve organizational well-being and health. With this support, clinic leaders prioritized physician well-being equal to care quality and financial viability. The new organization’s governing body built on ideas from others in developing the physician well-being program.20–23

During the study, the new organization underwent substantial changes, including clinician numbers growing from 22 to 32, doubling of sites from 3 to 6, additional midlevel leaders, and operational improvements partly based on clinician feedback (Hospitalist program, care-management program, and office design enhancements).

Intervention

In 2000, clinic leaders solicited the expertise of two of the authors (JC and BA) to develop the program, comprising 3 components: (1) leadership valuing physician well-being equal to quality of care and financial stewardship; (2) physicians identifying factors that influenced well-being, followed by plans for improvement with accountability; and (3) measuring the well-being of physicians regularly using validated instruments.

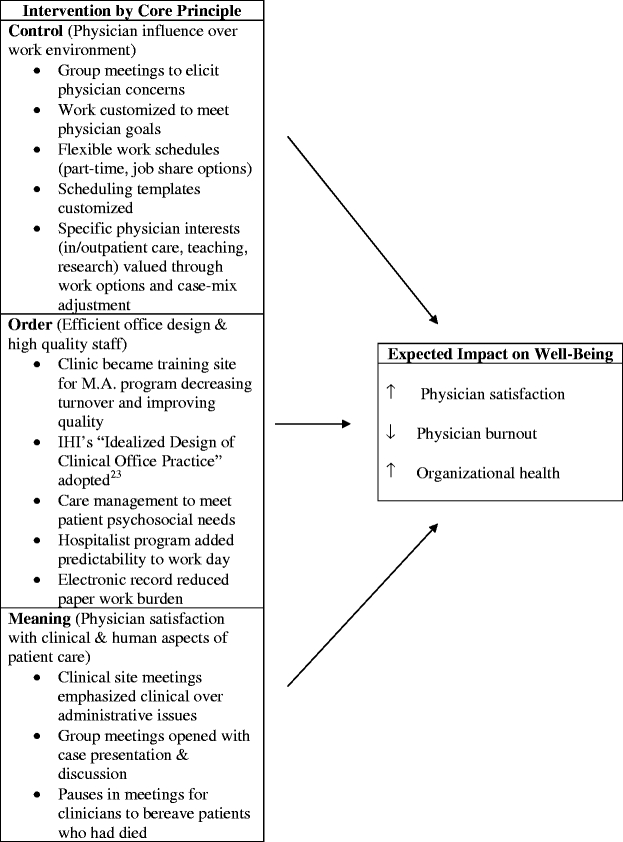

Leadership elicited from all physicians the factors affecting well-being at quarterly group meetings. Factors were prioritized under 1 of 3 core principles of control (physician influence over their work environment), order (efficient office design and high quality staff), and meaning (physicians’ satisfaction with the clinical and human aspects of care).24 Leaders then developed and implemented improvement plans for factors common to all sites. Staff at each site developed and implemented improvement plans for site-specific issues at weekly meetings. Leaders assessed progress monthly, revising plans with further physician input.

Table 1 describes the major organizational interventions, categorized by the 3 core principles of control, order, and meaning and their expected impact on physician and organizational well-being.

Table 1.

Organizational Interventions and Expected Impact on Well-being

Measuring Instruments

The overall effectiveness of the program was regularly evaluated using 3 instruments: a modified survey by the American College of Physicians/American Society of Internal Medicine (ACP/ASIM), the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), and the Quality Work Competence (QWC) Survey. These outcome measures of physician satisfaction, burnout, organizational health, including physician turnover are shown in Table 2 with years of data collection.

Table 2.

Outcome Measures and Years of Data Collection

| Outcomes Measures | Year of data collection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2005 | |

| ACP/ASIM (physician satisfaction) | X | X | X | X | X |

| Satisfaction | |||||

| Enter medical school today | |||||

| Consider changing positions | |||||

| Another medical position | |||||

| Non-medical position | |||||

| Retirement | |||||

| MBI (physician burnout) | X | X | X | X | X |

| Emotional exhaustion | |||||

| Depersonalization | |||||

| Personal accomplishment* | |||||

| QWC (organizational health) | X | X | X | X | X |

| Mental energy | |||||

| Work climate | |||||

| Work tempo | |||||

| Work-related exhaustion | |||||

| Performance feedback | |||||

| Participatory management | |||||

| Skills development | |||||

| Goal clarity | |||||

| Efficacy | |||||

| Leadership | |||||

| Employeeship | |||||

| Change focus | |||||

| Patient focus | |||||

| Quality of care | |||||

| Dynamic focus score | |||||

| Physician turnover | X | X | X | X | X |

*Personal accomplishment scores inversely related to burnout.

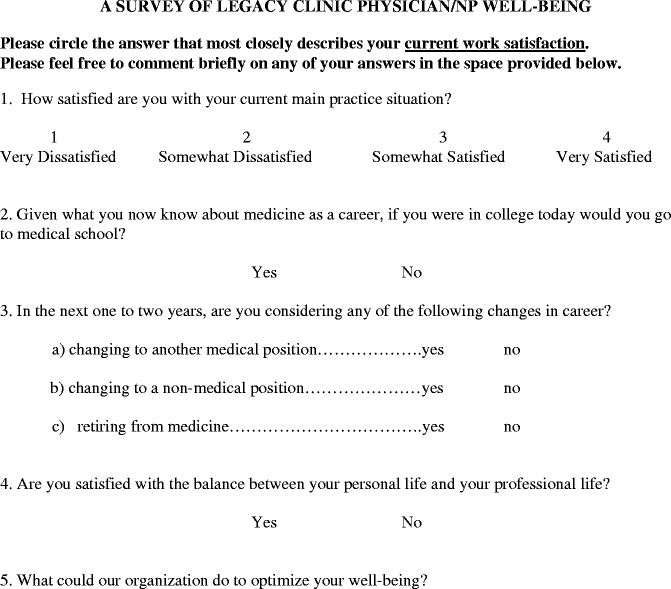

The ACP/ASIM is an unvalidated survey used to query members regarding work-life balance, satisfaction with work environment, and personal self-care practices (with permission, Deborah Kasman MD, VA Puget Sound Health Care System on behalf of the ACP/ASIM, Appendix).

The MBI is a 22-item standardized, validated instrument that assesses burnout.25 It contains 3 subscales measuring emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. Emotional exhaustion measures the depletion of emotional energy, that is, the extent to which individuals have lost the energy for emotional connection and may dissociate from their feelings. Depersonalization evaluates the presence of negative attitudes and feelings toward patients and coworkers. This aspect of burnout indicates the extent to which one treats others as objects useful in meeting one’s own goals. Personal accomplishment emphasizes effectiveness in having a beneficial impact on people and is inversely related to burnout.

The QWC Survey is a validated 42-item questionnaire that assesses 14 domains.21,26,27,28 These include mental energy, work climate, work tempo, work-related exhaustion, performance feedback, participatory management, skills development, goal clarity, efficacy, leadership, employeeship, change focus, patient focus, quality of care, and a dynamic focus score.29,30 The dynamic focus score offers a single, domain/scale-weighted measure of organizational and employee well-being. The QWC instrument has been validated using work performance, absenteeism, and biological stress markers in up to 220,000 individuals, many of whom work in health care.21,26 A work environment intervention reported beneficial effects on employee health, well-being, and productivity from QWC data-guided interventions.22

Physician turnover was determined for each year of the study using the industry standard metric: number of terminations / average employee count [(timeframe begin count + timeframe end count) / 2].

Assessments

The design was a noncontrolled prospective intervention study. Initially, the program was considered an internal quality improvement project not expecting future publication, so the program was reviewed retrospectively by the Legacy Institutional Review Board (IRB) and met the criteria for exemption from further review. Assessments using the 3 instruments were done in 2002, 2003, and 2005 with early data in 2000 and 2001 from the ACP/ASIM and MBI instruments. Leaders decided not to survey during 2004 owing to a prioritized delay of the assessment in the fall of 2003. Physicians were asked to complete each survey during a site meeting. Each survey was number-coded so that colleagues and leadership remained blind to individual results. Only an administrative assistant, QWC surveyor, and biostatistician (LH) knew the respondents’ identity. Results were reported confidentially to each physician, comparing personal scores to the combined mean scores of colleagues. Those with low well-being scores were encouraged to seek help. Based on the QWC experience, scores were analyzed in aggregate by sites and by the entire organization.15,22 Sites with less than 5 physicians were grouped with larger sites by geographic location for aggregate reports to protect anonymity. Results were presented annually at group meetings, and leadership followed-up discussions at site meetings to address concerns.

Statistical analyses for the ACP/ASIM and MBI surveys were done using ANOVA tests. For the QWC, changes over time were evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Student’s t test for unpaired and paired samples. Chi-square tests evaluated changes in proportions over time (e.g., percent of respondents being satisfied or not satisfied with their job). The QWC multivariate analysis included all subscales as dependent measures, except for the dynamic focus score, with year as the fixed factor. This evaluated the unique contribution of each QWC measure, controlling for all other scales simultaneously. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Voluntary participation rates for the 3 surveys for each year were: 100% in 2000, 100% in 2001, 97% in 2002, 90% in 2003, and 90% in 2005. The number of participating physicians ranged between 22 and 32 over the study period. The 3 complete surveys in 2002, 2003, and 2005 were completed in 20–30 minutes by each physician.

ACP/ASIM Survey

In 2001, 55% of physicians were either somewhat or very satisfied with their current practice. Only 59% would go to medical school if in college today. By 2003, 84% were either somewhat or very satisfied, and 75% would choose medical school. In 2005, 74% were either somewhat or very satisfied, and 77% would choose medical school. In 2001, none of the Legacy physicians were considering changing positions within 1–2 years. By 2003, 29% were considering a change to another medical position, 7% a nonmedical position, and 3% considering retirement. In 2005, the number considering changes was about the same as 2003. Satisfaction with personal and professional life balance varied by year: 71% satisfied in 2001, 50% in 2002, 66% in 2003, and 61% in 2005 (p = NS).

Maslach Burnout Inventory

In the first 4 years, Legacy physicians scored higher than national benchmarks for emotional exhaustion (mean ranged from 25 to 29; benchmark = 22.19), about the same for depersonalization (mean ranged from 6 to 8; benchmark = 7.12), and higher for personal accomplishment (mean ranged from 40 to 42; benchmark = 36.53, Table 3). The mean emotional exhaustion score was lower (25) in 2003 compared to prior years (27–29) and fell below benchmark in 2005 (21), p = 0.002. The depersonalization and personal accomplishment scores remained about the same for each year. The percentage of physicians scoring above the national sample burnout means for emotional exhaustion was 65.5% in 2000 and 45.1% in 2005 (Fisher exact test, p = 0.13). For depersonalization, these percentages were 34.5% (2001) and 35.0% (2005). For personal accomplishment, the percentages scoring below the national sample mean were 17.2% (2000) and 6.5% (2005).

Table 3.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Scores by Year Compared to National Benchmarks

| Legacy Clinic | National benchmarks | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBI subscales | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2005 | Low (lower third) | Average (middle third) | High (upper third) |

| Emotional exhaustion* | 27 | 29 | 29 | 25 | 21 | ≤16 | 17–26 | ≥27 |

| Depersonalization | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 6 | ≤6 | 7–12 | ≥13 |

| Personal accomplishment | 41 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 44 | ≤31 | 32–38 | ≥39 |

The physicians’ mean scores on the 3 subscales are compared by year to the mean national benchmarks. Lower scores are desired for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization; higher scores are desired for personal accomplishment.

*Scores not alike for all years by ANOVA. (Fdf–3,118 = 5.2, p = 0.002). The decrease in the last 2 years is statistically significant. Year 2002 not included.

Quality Work Competence (QWC) Survey

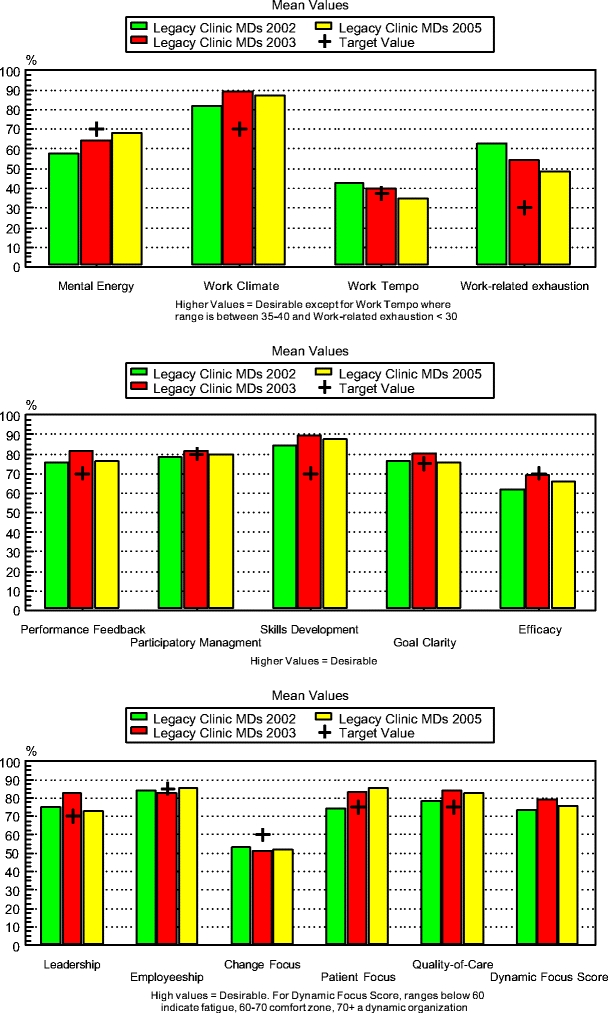

In 2002, QWC mean scores achieved levels that studies have determined to be desirable on 7 of 14 domains, including work climate, performance feedback, skills development, goal clarity, leadership, employeeship, and quality of care (Fig. 1). Scores indicating areas for improvement included mental energy, work tempo, work-related exhaustion, participatory management, efficacy, change focus, and patient focus.

Figure 1.

QWC domains by year. Changes over time in QWC, a series of validated subscales measuring organizational health and well-being, during the study. Changes in work-related exhaustion are statistically significant (p < 0.05). The dynamic focus score increased significantly from the 2002 to 2003 assessment (p < 0.045)

In 2003, physicians scored in the desirable range on 8 of 14 QWC domains including work climate, performance feedback, participatory management, skills development, goal clarity, leadership, patient focus, and quality of care (Fig. 1). Scores for work tempo and efficacy just met the desirable levels. Scores below the desirable levels were found for mental energy, work-related exhaustion, and change focus. The 2005 QWC mean scores met the recommended levels in 9 domains, 7 of these either unchanged or improved compared to prior assessments. The 3 domains of efficacy, mental energy, and work-related exhaustion remained areas for improvement but had improved since 2002. Change motivation was unchanged and leadership was lower than prior assessments. Both areas were below the recommended levels. Work-related exhaustion improved significantly comparing only 2002 (mean = 62.50, SD = 25.30) with 2005 (mean = 48.18, SD = 23.04) (Fdf 1,51 = 4.67, p = 0.035). The dynamic focus score improved significantly between 2002 (mean = 73.42, SD = 12.23) and 2003 (mean = 79.41 SD = 9.92) (Mann–Whitney U test = 255.00, p = 0.047), and remained at recommended levels for all assessments.

The intersubscale Pearson correlations between pairs of QWC scales were 0.45 or less except for a correlation of 0.52 between ratings of participatory management style and leadership. Thus, 1 subscale explains no more than 25% of the variance in any other QWC subscale.

QWC multivariate analysis revealed that work-related exhaustion significantly improved over the entire study period (Fdf–2 = 3.21, p = 0.046).

Physician Turnover

Annual physician turnover rates from 2000 to 2005 were 8%, 3%, 8%, 6%, and 15% with a mean for all years of 8%. Of the physicians who left the organization, 11 changed to primary care positions at another organization, 2 retired, and 1 entered a training program for a medical specialty. Annual staff turnover fell from 35% in 2001 to 15% in 2002.

DISCUSSION

This study critically assesses the impact of a reproducible organizational intervention program with the aim of promoting physician well-being at a multisite urban primary care group. Interventions were designed to increase physician control over their work environment, improve order in clinic functioning, and deepen the meaning physicians find in their work. Assessments reveal a significant decrease in emotional and work-related exhaustion.

The significant decrease in exhaustion, as measured by the MBI and QWC subscales, indicates an improvement in physician self-perceived capacity for empathy and emotional connection. This is a pivotal change that over time could lead to a decrease in depersonalization and increase in personal accomplishment and satisfaction. The capacity for emotional connection with patients and coworkers gives clinicians access to sources of energy renewal in the workplace, otherwise lost on one who is emotionally depleted and unable to connect. Finding renewal not only on weekends and vacations, but also at work, is vital to a sustainable career.

It is likely that strategic efforts to increase physicians’ control over their work environment (Table 1), particularly soliciting their input on the scheduling template and making adjustments to length of visits and case-mix, contributed to decreasing their emotional exhaustion. In a study of well-being among Kaiser Permanente physicians, 58% in 2 staff model HMO’s reported high emotional exhaustion.31 That study indicated that physicians’ sense of control over their practice environment was the greatest predictor of satisfaction, commitment to the organization, and personal/professional well-being. Low well-being, low work satisfaction, and practice-related concerns have also been reported in a large number of other studies.15,26–46 Despite the obvious need to assist physicians in enhancing their well-being at the same time as organizational processes are improved, there is little published data focusing on the evaluation of organizational-based interventions aimed at physician and organizational well-being. Most interventions target the individual physician with little connection to the organizational and social context within which that physician is practicing.

The QWC measures of organizational health indicated that 3 domains—efficacy, mental energy, and work-related exhaustion—showed steady improvement since 2002. Of those, improvement in work-related exhaustion was statistically significant, even when multivariate statistics were applied to control for the possible influence from other domains assessed simultaneously. Efficacy indicates satisfaction with work planning, orientation toward a common goal, an effective decision-making process, and optimization of resource allocation and use. Mental energy is a marker for a relative absence of restlessness, irritation, moodiness, anxiety, and impaired concentration among those responding to the survey. Work-related exhaustion refers to feeling emotionally drained and tired after work. Taken together, the positive trends on these dimensions suggest that physicians perceived and appreciated increased order in their work environment and that subjectively they felt less distressed after the implementation of the intervention.

The improvement noted in physicians’ perceived capacity for emotional connection and their sense of reduced distress and burnout occurred against a backdrop of decreased satisfaction among Oregon and U.S. physicians.1,2,33 Thus, programs such as the one presented in this study might be an important mitigator, at least partially, of the continuous slide in physician well-being and job satisfaction. The organization will also benefit. Physicians who are more satisfied with their work tend to be more productive.8,22,30,31 Work satisfaction also enhances efforts in recruitment and retention of physicians.20,47,48,49 Estimates indicate that replacing 1 primary care physician can result in $20,000 to $26,000 in recruitment costs, loss of $300,000 to $400,000 in annual gross billings, loss of $300,000 to $500,000 in inpatient revenue, plus additional losses of specialty referral revenue.47 Rates of yearly physician turnover range from 10% to 15% nationally,47 comparable to the current study. Furthermore, distressed physicians have higher medical error rates, increasing malpractice risk, and associated costs to the organization.3,25,50 An effective well-being program can help mitigate these losses.

Implementing this program provided key lessons to the organization. First, establishing physician well-being as an essential value of the organization helps create the intended culture. Second, a regular iterative process of inquiry and feedback from physicians can identify issues that negatively affect well-being and barriers to improvement. Third, assessment of well-being using reliable and valid instruments further establishes the value and creates a common language that can help physicians and the organization address well-being issues.

There are several limitations to this study. The program was applied to a relatively small, newly formed employed physician group that experienced substantial change over the 4-year study. The small number of physicians limits the statistical power to detect changes in outcome measures over time. Also, as expected for a young growing organization, physician turnover was significant, although similar to groups nationally. Improvements in well-being measures might be attributable to dissatisfied physicians leaving the organization, replaced by more positive colleagues. A substantially larger and more stable cohort would be needed to detect smaller changes in physician and organizational well-being. From prior experiences using QWC, observed changes in the current study are fewer than expected. This may indicate a limited ability for Legacy Clinic to sustain improvement processes. Future studies need to better describe in more detail the ingredients of interventions, intensity of their use, and degree of adoption by the organization.

Although the program showed a number of positive trends, based on the years of dedicated leadership and physician efforts, results show needed improvements. The key elements of this program, however, and the principle of applying data-guided interventions are applicable to health care organizations that face the challenge of increasing productivity in times of increasing physician discontent.

Caring for others in an ever more constrained world of regulation and productivity demands, physicians increasingly sense an erosion of control. The tide of physician distress and burnout over the last several years is rising. Given the negative consequences to patients, physicians, and their organizations, it is imperative that leadership gives well-being the prominence it deserves.51,52 Only by applying robust measures of well-being, engaging physicians in reflection and conversation about promoting it in the workplace, tracking it as a meaningful outcome, and making changes to enhance its realization, will physicians and their organizations thrive in their service to patients.

Acknowledgement

We thank Jennifer Basada for her dedication to the overall coordination and management of the Legacy Clinic Physician Well-Being Program. We also thank Charlene Tucker for her help in manuscript preparation. Finally, we thank Jonathan Avery for his guidance in developing the program; Malcolm McAninch, John Teller, Gwen Grewe, and Marylee Morris for the implementation; and Keith Marton and Stephen R. Jones for critically reviewing the manuscript and for encouraging a nurturing environment to enhance physician health and well-being.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest QWC is a commercial product marketed and sold by the Sweden-based company Springlife AB, Bengt B. Arnetz is a majority owner of this company.

APPENDIX

ACP/ASIM Physician Well-being Survey Instrument (Adapted with permission from a survey developed by Deborah Kasman, MD, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, on behalf of the ACP/ASIM)

References

- 1.Murray A, Montgomery JE, Chang H, Rogers WH, Inui T, Safran DG. Doctor discontent. A comparison of physician satisfaction in different delivery system settings, 1986 and 1997. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:452–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Williams ES, Konrad TR, Scheckler WE, et al. Understanding physicians’ intentions to withdraw from practice: the role of job satisfaction, job stress, mental and physical health. Health Care Manage Rev. 2001;26:7–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Crane M. Why burned-out doctors get sued more often. Med Econ. 1998;75:210–2, 215–8. [PubMed]

- 4.Myers MF. Doctors’ Marriages. A Look at the Problems and their Solutions. Second Edition. New York: Plenum Medical Book Company; 1994.

- 5.Rollman BL, Mead LA, Wang NY, Klag MJ. Medical specialty and the incidence of divorce. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:800–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gross CP, Mead LA, Ford DE, Klag MJ. Physician, heal thyself? Regular source of care and use of preventive health services among physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3209–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Baruch-Feldman C, Brondolo E, Ben-Dayan D, Schwartz J. Sources of social support and burnout, job satisfaction, and productivity. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7:84–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Canadian Medical Association. CMA policy. Physician health and well-being. CMAJ. 1998;158:1191–200. [PubMed]

- 10.Spickard A Jr, Gabbe SG, Christensen JF. Mid-career burnout in generalist and specialist physicians. JAMA. 2002;288:1447–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.O’Connor PG, Spickard A Jr. Physician impairment by substance abuse. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:1037–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Brewster JM. Prevalence of alcohol and other drug problems among physicians. JAMA. 1986;255:1913–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Pincus CR. Have doctors lost their work ethic? Med Econ. 1995;72:24–30. [PubMed]

- 14.Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Arnetz BB. Psychosocial challenges facing physicians of today. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:203–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Bowman B. Sick docs get cold comfort from colleagues. National Review of Medicine. Available at: http://www.nationalreviewofmedicine.com/issue/2005/11_15/2_patients_practice05_19.html. Accessed July 26, 2007.

- 17.Suchman A. The influence of health care organizations on well-being. West J Med. 2001;174:43–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Christensen J, Feldman M. (Guest Editors). Recapturing the spirit of medicine (special issue on physician well-being) West J Med. 2001;174:1–80.

- 19.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Medical staff revisions reflect current practices in the field. Jt Comm Perspect. 2000,20:9,13. [PubMed]

- 20.Scott K. Physician retention plans help reduce costs and optimize revenues. Healthc Financ Manage. 98;52:75–7. [PubMed]

- 21.Arnetz BB. Techno-stress: a prospective psychophysiological study of the impact of a controlled stress-reduction program in advanced telecommunication systems design work. J Occup Environ Med. 1996;38:53–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Anderzén I, Arnetz BB. The impact of a prospective survey-based workplace intervention program on employee health, biologic stress markers, and organizational productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:671–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Berwick D, Kilo C. Idealized design of clinical office practice: an interview with Donald Berwick and Charles Kilo of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Manag Care Q. 1999;7:62–9. [PubMed]

- 24.Frankel VE. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. Third Edition. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1984.

- 25.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Research Edition. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1981.

- 26.Arnetz BB. Staff perception of the impact of health care transformation on quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999;11:345–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Wallin L, Ewald U, Wikblad K, Scott-Findlay S, Arnetz BB. Understanding work contextual factors: a short-cut to evidence-based practice? Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2006;3:153–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Arnetz B, Blomkvist V. Leadership, mental health, and organizational efficacy in health care organizations. Psychosocial predictors of healthy organizational development based on prospective data from four different organizations. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:242–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Arnetz BB. Physicians’ view of their work environment and organisation. Psychother Psychosom. 1997;66:155–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Arnetz BB. Subjective indicators as a gauge for improving organizational well-being. An attempt to apply the cognitive activation theory to organizations. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:1022–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Freeborn DK. Satisfaction, commitment, and psychological well-being among HMO physicians. Perm J. 1998;2:22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Edwards N, Kornacki MJ, Silversin J. Unhappy doctors: what are the causes and what can be done? BMJ. 2002;324:835–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Oregon Medical Association. Report of the 2004 Oregon Physician Workforce Survey Report of Results. Available at: http://www.oregon.gov/DHS/healthplan/data_pubs/reports/04opsurvey.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2007.

- 34.Bargellini A, Barbieri A, Rovesti S, Vivoli R, Roncaglia R, Borella P. Relation between immune variables and burnout in a sample of physicians. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:453–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.McCall L, Maher T, Piterman L. Preventive health behavior among general practitioners in Victoria. Aust Fam Physician. 1999;28:854–7. [PubMed]

- 36.Schwartz JS, Lewis CE, Clancy C, Kinosian MS, Radany MH, Koplan JP. Internists’ practices in health promotion and disease prevention. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Wachtel TJ, Wilcox VL, Moulton AW, Tammaro D, Stein MD. Physicians’ utilization of health care. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:261–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Kahn KL, Goldberg RJ, DeCosimo D, Dalen JE. Health maintenance activities of physicians and nonphysicians. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2433–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Rosen IM, Christie JD, Bellini LM, Asch DA. Health and health care among housestaff in four U.S. internal medicine residency programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:116–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Doan-Wiggins L, Zun L, Cooper MA, Meyers DL, Chen EH. Practice satisfaction, occupational stress, and attrition of emergency physicians. Wellness Task Force, Illinois College of Emergency Physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:556–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, et al. Managed care, time pressure, and physician job satisfaction: results from the physician worklife study. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Frank E, McMurray JE, Linzer M, Elon L. Career satisfaction of US women physicians: results from the Women Physicians’ Health Study. Society of General Internal Medicine Career Satisfaction Study Group. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1417–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Doherty WJ, Burge SK. Divorce among physicians. Comparisons with other occupational groups. JAMA. 1989;261:2374–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Arnetz BB, Ekman R. Stress in Health and Disease. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2006:122–40.

- 45.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Forsberg E, Axelsson R, Arnetz B. Effects of performance-based reimbursement on the professional autonomy and power of physicians and the quality of care. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2001;16:297–310. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Buchbinder SB, Wilson M, Melick CF, Powe NR. Estimates of costs of primary care physician turnover. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:1431–8. [PubMed]

- 48.Landon BE, Reschovsky JD, Pham HH, Blumenthal D. Leaving medicine: the consequences of physician dissatisfaction. Med Care. 2006;44:234–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Crouse BJ. Recruitment and retention of family physicians. Minn Med. 1995;78:29–32. [PubMed]

- 50.Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1017–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Suchman A. The influence of health care organizations on well-being. West J Med. 2001;174:43–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Quill TE, Williamson PR. Healthy approaches to physician stress. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1857–61. [DOI] [PubMed]