Abstract

BACKGROUND

Disease registries, audit and feedback, and clinical reminders have been reported to improve care processes.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the effects of a registry-generated audit, feedback, and patient reminder intervention on diabetes care.

DESIGN

Randomized controlled trial conducted in a resident continuity clinic during the 2003–2004 academic year.

PARTICIPANTS

Seventy-eight categorical Internal Medicine residents caring for 483 diabetic patients participated. Residents randomized to the intervention (n = 39) received instruction on diabetes registry use; quarterly performance audit, feedback, and written reports identifying patients needing care; and had letters sent quarterly to patients needing hemoglobin A1c or cholesterol testing. Residents randomized to the control group (n = 39) received usual clinic education.

MEASUREMENTS

Hemoglobin A1c and lipid monitoring, and the achievement of intermediate clinical outcomes (hemoglobin A1c <7.0%, LDL cholesterol <100 mg/dL, and blood pressure <130/85 mmHg) were assessed.

RESULTS

Patients cared for by residents in the intervention group had higher adherence to guideline recommendations for hemoglobin A1c testing (61.5% vs 48.1%, p = .01) and LDL testing (75.8% vs 64.1%, p = .02). Intermediate clinical outcomes were not different between groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Use of a registry-generated audit, feedback, and patient reminder intervention in a resident continuity clinic modestly improved diabetes care processes, but did not influence intermediate clinical outcomes.

KEY WORDS: education, medical; health care quality; diabetes mellitus; outcome assessment; registries

BACKGROUND

Numerous reports document deficiencies in adherence to health care recommendations and emphasize the need for improved health care quality.1,2

Chronic disease registries,3–5 audit and feedback,6 and physician and patient reminders7,8 can improve care processes. However, these methods demonstrate inconsistent improvement in diabetes clinical outcomes.9

A study assessing diabetes registry implementation in our Internal Medicine (IM) faculty practice found improvements in process and intermediate clinical outcomes using registry-generated audit and feedback combined with automated patient reminders.10 Whether the benefits of such a system are transferable to a resident practice is unknown. We aimed to integrate registry-generated audit, feedback, and patient reminders into an IM resident continuity clinic and to assess the effects on diabetes care processes and intermediate clinical outcomes in this setting.

METHODS

Setting

This study was conducted in the IM Residency Continuity Clinics at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA during academic year 2003–2004. In these clinics, 3 residents (1 postgraduate year 1, 2, and 3) were supervised together weekly by a consistent preceptor. Residents in each group cover each other during absences.

Participants

Categorical IM residents with community-based continuity clinic were eligible to participate. Residents anticipating early residency completion were excluded.

Study Design

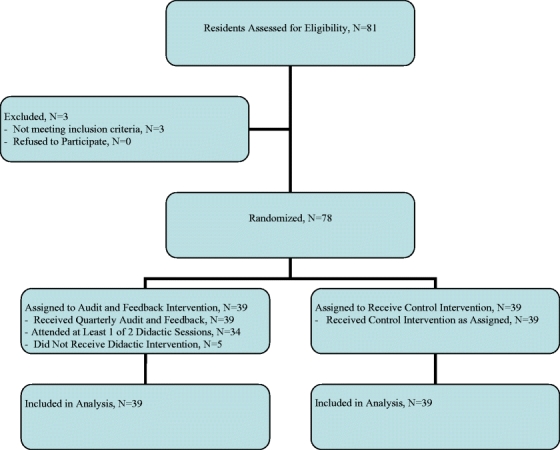

Clinic groups (of 3 residents) were randomized to receive a registry-generated audit, feedback, and patient reminder intervention or control (Fig. 1). Randomization was stratified by clinic day and across 5 practice sections.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram

Intervention

The audit, feedback, and patient reminder intervention utilized a computerized diabetes registry that provided physicians information on all their patients with diabetes. The registry was electronically integrated with other clinical information systems, automatically queried clinical databases, and reported summaries without manual effort. Information was organized by evidence-based guidelines, highlighting relevant data.

Residents randomized to the intervention received two 1-hour sessions introducing registries, describing their value in practice improvement, and providing instruction on registry use. Residents were encouraged to independently access their registry data. Quarterly, residents were provided registry-generated feedback comparing their diabetes performance metrics to aggregate resident performance. Residents also received registry-generated lists identifying patients not in compliance with guideline recommendations. Letters recommending appropriate surveillance tests were automatically sent quarterly to patients without hemoglobin (Hgb) A1c measurement within 6 months or LDL cholesterol measurement within 12 months.

Control

Residents randomized to the control group received usual clinic education consisting of faculty review of diabetes care among patients supervised with the resident. All residents had access to the ‘Electronic Curriculum for Diabetes Care’ generated and maintained by the Residency Program.

Measurements

Diabetes care metrics were obtained for all participating residents’ patients at study inception and completion including HgbA1c monitoring in the prior 6 months and lipid monitoring in the prior 12 months. Intermediate clinical outcomes were based on the most recent assessment and included achievement of HgbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and blood pressure control. Targets were based on the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) guidelines;11 HgbA1c <7%, LDL cholesterol <100 mg/dL, and blood pressure <130/85 mmHg. Resident use of the registry was assessed at study completion using a web-based survey.

Statistical Analysis

Diabetes process metrics and intermediate clinical outcomes were assessed between groups with a generalized estimating equations (GEE) model with repeated measurements per subject using the GENMOD procedure from SAS, version 9.1 (Cary, NC, USA). This model incorporates the clustered nature of the randomization scheme and accounts for the correlation of patient measurements clustered within a resident and residents within faculty preceptors.12,13 A p value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using intention to treat principles. The study had 80% power to detect 12% improvement in HgbA1c and lipid monitoring, 12% improvement in percent of patients with glucose control (HgbA1c<7%) and lipid control (LDL<100 mg/dL), and 12.6% improvement in blood pressure control (<130/85 mmHg) in the intervention compared to the control group. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

All eligible residents (n = 78) consented to participate and were randomized into intervention (n = 39) and control groups (n = 39). Resident demographic data (age, sex, and year in training) were similar between groups. All residents randomized to the intervention received registry-generated audit, feedback, and patient reminders quarterly. Thirty-four (87.2%) intervention residents attended at least 1 didactic session on diabetes registry use (Fig. 1). Diabetes care metrics were obtained for all residents who collectively cared for 483 diabetic patients.

At baseline, there were no significant differences in HgbA1c, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure levels, or adherence to HgbA1c or LDL cholesterol monitoring guidelines between patients cared for by residents in intervention and control groups.

At study completion, patients cared for by residents in the intervention group had higher rates of adherence to recommended diabetes care processes than patients cared for by residents in the control group (Table 1). Compared to the control group, patients in the intervention group were more likely to have HgbA1c measured within 6 months (61.5% vs 48.1%; p = .01) and more likely to have LDL cholesterol measured within 12 months (75.8% vs 64.1%; p = .02). Intermediate clinical outcomes including HgbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and blood pressure were similar between groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Effect of Registry-Generated Audit, Feedback, and Patient Reminders on Diabetes Care Outcomes in an Internal Medicine Resident Clinic

| Diabetes care outcomes in the intervention group | Diabetes care outcomes in the control group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process outcomes | |||

| No. of patients who had HgbA1c monitoring within 6 mo | 155 of 252 (61.5%) | 111 of 231 (48.1%) | .01 |

| No. of patients who had LDL cholesterol monitoring within 1 yr | 191 of 252 (75.8%) | 148 of 231 (64.1%) | .02 |

| Intermediate clinical outcomes | |||

| HgbA1c | |||

| No. of patients with HgbA1c <7.0% | 156 of 252 (62%) | 135 of 231 (58%) | .42 |

| Mean HgbA1c (95%CI), baseline | 7.3 (7.1–7.5) | 7.4 (7.2–7.7) | .13 |

| Mean HgbA1c (95%CI), end of study | 7.3 (7.1–7.5) | 7.4 (7.1–7.6) | .38 |

| Mean reduction HgbA1c (95%CI) | −0.02 (−0.18–0.14) | −0.01 (−0.13–0.12) | .83 |

| LDL cholesterol | |||

| No. of patients with LDL <100 mg/dL | 152 of 252 (60%) | 141 of 231 (61%) | .76 |

| Mean LDL cholesterol (95%CI), baseline | 103.6 (98.9–108.3) | 101.6 (97.1–106.1) | .14 |

| Mean LDL cholesterol (95%CI), end of study | 98.4 (94.0–102.9) | 97.5 (93.0–102.0) | .60 |

| Mean reduction LDL cholesterol, (95%CI) | −4.9 (−7.8–−2.0) | −4.0 (−6.7–−1.4) | .61 |

| BP | |||

| No. of patients with BP <130/85 mmHg | 126/252 (50%) | 116/231 (50%) | .96 |

| Mean systolic blood pressure (95%CI), baseline | 131.5 (129.1–133.9) | 129.1 (126.4–131.7) | .20 |

| Mean systolic blood pressure (95%CI), end of study | 131.0 (128.5–133.5) | 130.8 (128.0–133.6) | .93 |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure (95%CI), baseline | 72.6 (71.6–73.8) | 72.01 (70.5–73.5) | .79 |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure (95%CI), end of study | 72.4 (70.9–73.8) | 71.7 (70.2–73.2) | .64 |

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that registry-generated audit, feedback, and patient reminders can improve adherence to diabetes care processes in an IM resident continuity clinic. Improvements in intermediate clinical outcomes were not observed. These findings are consistent with those described in a systematic review of diabetes management interventions in physician practices in which computerized reminders, audit and feedback, or a combination of these improved process measures, but not necessarily achievement of disease management targets.9

Improved adherence to recommended care processes has been demonstrated using different types of computerized reminders.7,8 One large randomized trial demonstrated improvements in resident compliance with multiple care standards using a registry-generated computerized reminder system that provided physician reminders coordinated with patients’ appointments.7 In contrast to our study, this intervention did not include performance feedback or patient reminders. The response seen with this physician reminder intervention declined over time, suggesting that additional interventions, such as those in our study, may be needed to sustain positive effects.

Process improvements have also been variably reported using audit and feedback.6,14–18 One randomized controlled trial using chart audit of 10–12 patients per resident, report cards assessing 78 audit items, and a 10- to 15-minute feedback session did not demonstrate improved patient management.19 Possible reasons for the lack of benefit with this approach include the limited number of patients assessed per resident; diffuse nature of the feedback; and the single, brief feedback session. In contrast, our audit and feedback intervention provided feedback regarding a resident’s entire panel of diabetic patients, focused on a single disease, and incorporated regular performance review. In addition, feedback provided in our study included identification of specific patients needing care, allowing residents to take directed action.

Two studies using audit and feedback in educational settings demonstrated improvements in intermediate clinical outcomes.14,17 In contrast to our study, which did not affect intermediate clinical outcomes, these interventions included additional educational components such as readings in quality of care, self-reflection, commitment to change surveys, and learner involvement in quality improvement processes. Whereas this suggests that multifaceted interventions may be beneficial, a systematic review of 85 audit and feedback studies did not find evidence that multifaceted interventions were more effective than audit and feedback alone.6

This study has several limitations. First, resident participation in the intervention was incomplete. All residents in the intervention group received quarterly audit, feedback, and patient reminders and 87.2% attended at least 1 didactic session on diabetes registry use, however, only 59.0% completed both didactic sessions. Although lack of participation in didactic sessions might be expected to decrease registry use, 91.7% of residents in the intervention group responding to a post study survey reported using the diabetes registry in clinic. Second, we were unable to quantify differential effects of intervention components. Third, blinding was not possible because of the nature of the intervention. Attempts to minimize the Hawthorne effect were made by limiting information regarding study intervention and outcome measures to participating residents.

In summary, this study demonstrates that the integration of a registry-generated audit, feedback, and patient reminder intervention into a resident continuity clinic can result in modest improvement in diabetes care processes. These findings add to a growing body of literature demonstrating the potential of information technology tools to improve care delivery when integrated into comprehensive chronic care models. Driven in part by results from this and other studies at our institution,10,20 our resident continuity clinics are being integrated into developing care systems. Our institution is currently working to refine a more comprehensive disease management system to replace the original diabetes registry. This system will serve as a population management tool and will provide point of care decision support prompting recommended care for preventive services and additional chronic diseases. Resident involvement in chronic care systems is important for competency-based education in practice-based learning and improvement and systems-based practice and allows residents to learn elements of the quality improvement process. Future studies are anticipated to assess educational outcomes resulting from resident use of enhanced clinical systems and to determine whether improved processes of care will ultimately result in improved clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by an Education Innovation Award, provided by the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The primary author had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- 2.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(6):64–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Schmittdiel J, Bodenheimer T, Solomon NA, Gillies RR, Shortell SM. Brief report: the prevalence and use of chronic disease registries in physician organizations. A national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):855–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, Thomson O’Brien MA, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003(3):CD000259. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Demakis JG, Beauchamp C, Cull WL, et al. Improving residents’ compliance with standards of ambulatory care: results from the VA Cooperative Study on Computerized Reminders. JAMA. 2000;284(11):1411–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3(6):399–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, Wagner EH, Eijk JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004(1):CD001481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Stroebel RJ, Scheitel SM, Fitz JS, et al. A randomized trial of three diabetes registry implementation strategies in a community internal medicine practice. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28(8):441–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Mosser G. Clinical process improvement: engage first, measure later. Qual Manag Health Care. 1996;4(4):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang K, Zeger S. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. 2 ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2002.

- 13.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:43–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Holmboe ES, Prince L, Green M. Teaching and improving quality of care in a primary care internal medicine residency clinic. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):571–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kern DE, Harris WL, Boekeloo BO, Barker LR, Hogeland P. Use of an outpatient medical record audit to achieve educational objectives: changes in residents’ performances over six years. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(3):218–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Holmboe E, Scranton R, Sumption K, Hawkins R. Effect of medical record audit and feedback on residents’ compliance with preventive health care guidelines. Acad Med. 1998;73(8):901–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Gould BE, Grey MR, Huntington CG, et al. Improving patient care outcomes by teaching quality improvement to medical students in community-based practices. Acad Med. 2002;77(10):1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Denton GD, Smith J, Faust J, Holmboe E. Comparing the efficacy of staff versus housestaff instruction in an intervention to improve hypertension management. Acad Med. 2001;76(12):1257–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Kogan JR, Reynolds EE, Shea JA. Effectiveness of report cards based on chart audits of residents’ adherence to practice guidelines on practice performance: a randomized controlled trial. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Chaudhry R, Scheitel SM, McMurtry EK, Leutink DJ, Cabanela RL, Naessens JM, Rahman AS, Davis LA, Stroebel RJ. Web-based proactive system to improve breast cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(6):606–11. [DOI] [PubMed]