Abstract

The zebrafish embryo is an excellent system for studying dynamic processes such as cell migration during vertebrate development. Dynamic analysis of neuronal migration in the zebrafish hindbrain has been hampered by morphogenetic movements in vivo, and by the impermeability of embryos. We have applied a recently reported technique of embryo explant culture to the analysis of neuronal development and migration in the zebrafish hindbrain. We show that hindbrain explants prepared at the somitogenesis stage undergo normal morphogenesis for at least 14 h in culture. Importantly, several aspects of hindbrain development such as patterning, neurogenesis, axon guidance, and neuronal migration are largely unaffected, inspite of increased cell death in explanted tissue. These results suggest that hindbrain explant culture can be employed effectively in zebrafish to analyze neuronal migration and other dynamic processes using pharmacological and imaging techniques.

Keywords: Zebrafish hindbrain, Explant culture, Rhombomere, Motor neuron, Neuronal migration, Time-lapse microscopy, Green fluorescent protein

1. Introduction

The transparent zebrafish embryo is an established model system for studying vertebrate development. The zebrafish is genetically manipulable, leading to the identification, by microscopic observation of live embryos, of hundreds of mutations affecting embryonic patterning and morphogenesis (Haffter et al., 1996; Driever et al., 1996). Moreover, the transparency of the embryo has facilitated the observation and analysis of dynamic cellular processes during epiboly and gastrulation (Warga and Kimmel, 1990; Concha and Adams, 1998; Jessen et al., 2002), hematopoieisis (Herbomel et al., 1999), neuronal migration (Koster and Fraser, 2001; Jessen et al., 2002), and growth cone guidance (Eisen et al., 1986; Hutson and Chien, 2002; Gilmour et al., 2002).

Despite the obvious advantages of observing dynamic processes in the intact embryo, there are experimental limitations to this approach. First, most studies thus far have analyzed dynamic cellular processes occurring in superficial embryonic tissues that can be imaged at high resolution, while deeper tissues especially in the head have been less accessible due to the curvature of the head around the yolk cell. Second, immobilization of intact embryos for long-term observations (3 h or longer) hinders normal morphogenetic movements, potentially affecting the process under observation. Finally, the embryonic skin is tough and quite impermeable, potentially precluding the use of many pharmacological reagents that have been used very effectively to study dynamic processes in cultured cells.

To overcome these problems, Langenberg et al. (2003) devised a culture system that supports growth and development of a deyolked zebrafish embryo over long time periods. Furthermore, this culture system was conducive to the observation of dynamic processes in explants of the zebrafish nervous system (Langenberg et al., 2003). However, before the explant culture technique can be used for studying particular cell types, one must rigorously test whether the explanted tissue in the region of interest preserves the native (endogenous) environment, and whether the cell type to be studied behaves normally in explant culture. We are investigating the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying facial branchiomotor neuron (FBMN) migration in the zebrafish hindbrain (Bingham et al., 2002; Jessen et al., 2002; Chandrasekhar, 2004). FBMN migration has been intensively studied in mouse (Garel et al., 2000; Studer, 2001) and zebrafish (our work; Cooper et al., 2003) as a model for tangential neuronal migrations in the vertebrate brain (Marin and Rubenstein, 2001). Therefore, we investigated whether zebrafish explant culture could be another tool in our studies of FBMN migration. We show here that tangential (caudal) migration of FBMNs occurs normally in cultured hindbrain explants. The explants remain healthy for at least 14 h in culture, and several aspects of hindbrain development and patterning are mostly unaffected. These observations indicate that the analysis of FBMN migration in hindbrain explants is a powerful complementary approach to the analysis of this dynamic process in the intact zebrafish embryo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Maintenance of zebrafish stocks, and collection and development of embryos in E3 embryo medium were carried out as described previously (Westerfield, 1995; Chandrasekhar et al., 1997; Bingham et al., 2002). To facilitate analysis of branchiomotor neuron development, fish carrying the motor neuron-expressed islet1-GFP transgene (Higashijima et al., 2000) were used to obtain embryos for all experiments. Throughout the text, the developmental age of the embryos corresponds to the hours elapsed since fertilization (hours post fertilization, hpf, at 28.5 °C).

2.2. Explant preparation and mounting

The procedures for removing the yolk cell, generating explants, and mounting for observation were essentially the same as those described previously (Langenberg et al., 2003; Fig. 1), with the following modifications. The non-hydrolyzable ATP analog (AMP-PNP, Sigma) was prepared to a concentration of 50 mM by dissolving in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% phenol red. The stock L-15 amphibian culture medium (GibcoBRL) was diluted to 67% with sterile water, and supplemented with tissue culture penicillin/streptomycin cocktail (1× final), and 1 M glucose (10 mM final). Following AMP-PNP injection, embryos were deyolked in sterile E3, washed twice in E3, transferred and maintained in L-15 solution (80% stock L-15, 20% sterile E3) until all explants were ready for extended incubation. Hindbrain explants were obtained by cutting deyolked embryos with a fine scissors in the rostral spinal cord. For long-term culture, up to eight explants were transferred under sterile conditions to a well in 24-well tissue culture plates containing 1 ml/well 67% L-15 medium (see above). Control embryos were dechorionated and incubated in identical conditions to explants.

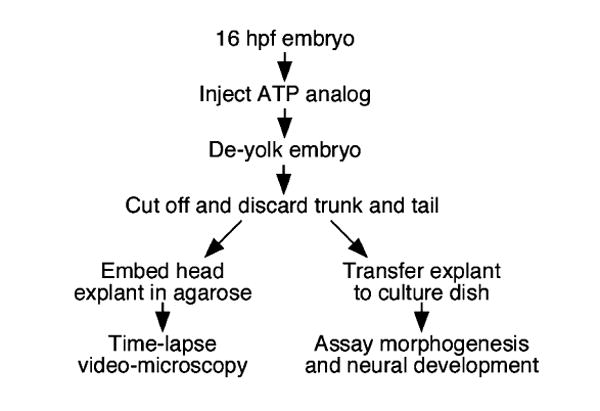

Fig. 1.

Generation and analysis of hindbrain explants. Embryos were injected with the ATP analog (AMP-PNP) in the yolk cell. Following yolk removal, the embryo was decapitated, and the head fragment containing the hindbrain was either embedded in agarose for imaging and video microscopy or transferred to culture medium for assaying morphogenesis and neural development at subsequent stages. (see Section 2 for details).

Embryos or hindbrain explants were embedded in 0.4% agarose for time-lapse microscopy. Briefly, an explant or embryo was transferred to a 1.5 ml microfuge tube containing 200 μl of 100% L-15 medium, supplemented with Penicillin/Streptomycin cocktail and glucose (but no water). To this tube, 100 μl of melted agarose solution (1.2% agarose dissolved in sterile water, and maintained at 55 °C) was added, mixed gently, and the tissue was manipulated into the desired orientation in a small drop of agarose/L-15 solution placed on a pre-warmed microscope slide. Upon gelling, the agarose above the area of interest was gently removed, the agarose drop was covered with 67% L-15 solution, and the explant/embryo was observed using long-working distance objectives on an Olympus BX60 microscope. Bodipy ceramide labeling (to assay neuroepithelial cell shapes) and acridine orange labeling (to assay cell death) of explants and embryos were performed essentially as described (Brand et al., 1996; Cooper et al., 1999), and the tissue was embedded as described above. Acridine orange-labeled tissue was imaged using epifluorescence on the BX60 microscope, and bodipy ceramide-labeled tissue was imaged on an Olympus IX70 microscope equipped with a BioRad Radiance 2000 confocal laser system.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and imaging

Whole-mount immunohistochemistry was performed with various antibodies as described previously (Chandrasekhar et al., 1997; Bingham et al., 2002; Vanderlaan et al., 2005). Synthesis of the digoxygenin- and fluorescein-labeled probes, and whole-mount in situ hybridization were carried out as described previously (Chandrasekhar et al., 1997; Prince et al., 1998; Bingham et al., 2003). Two-color in situs were performed essentially as described (Prince et al., 1998; Vanderlaan et al., 2005).

Embryos were deyolked, mounted in 70% glycerol, and examined with an Olympus BX60 microscope. For confocal imaging, fixed embryos were mounted in glycerol, and viewed under an Olympus IX70 microscope (see above). In all comparisons, at least five intact embryos and five explanted hindbrains were examined.

3. Results

3.1. Tangential (caudal) migration of facial branchiomotor neurons (FBMNs) occurs normally in hindbrain explants

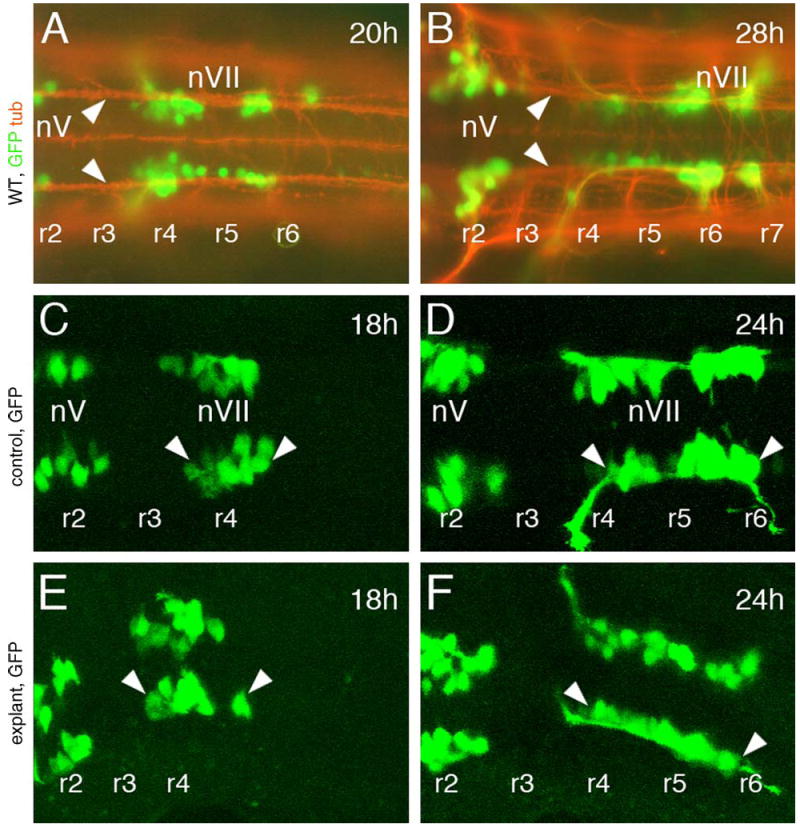

The FBMNs (nVII motor neurons) are increasingly being utilized as a model system for understanding neuronal migrations in the vertebrate brain (Chandrasekhar, 2004). While in vivo analysis of their migratory behaviors is difficult at best in a mouse embryo, we have performed in vivo analysis of FBMN migration in the zebrafish embryo (Bingham et al., 2002; Jessen et al., 2002). To overcome some limitations of the current methods, we tested the utility of an explant technique (Langenberg et al., 2003) for the analysis of FBMN migration (Fig. 1). In zebrafish embryos, FBMNs begin differentiating by 15 hpf (hours post fertilization) in rhombomere 4 (r4) and undergo tangential neuronal migration into r6 and r7 (Chandrasekhar et al., 1997). FBMN development can be readily examined using a transgenic line expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the motor neuron-expressed islet1 promoter (Higashijima et al., 2000). FBMNs appear to be associated with the axons of the ventral longitudinal fascicles (VLF) throughout their migratory pathway in rhombomeres 4–7 (r4–r7) (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting that the VLF may provide a substrate for motor neuron migration. In intact control embryos, FBMNs begin to accumulate in r4 by 18 hpf, and have undergone substantial migration into r6 by 24 hpf (Fig. 2C and D). Similarly, in hindbrain explants, FBMNs accumulate in r4 by 18 hpf and migrate caudally into r5 and r6 by 24 hpf (Fig. 2E and F), indicating that motor neuron migration into posterior rhombomeres is not compromised by the procedure of deyolking embryos, and preparing and culturing explants in vitro.

Fig. 2.

Facial branchiomotor neurons (FBMNs) develop and migrate normally in hindbrain explants. All panels show dorsal views of the hindbrain, with anterior to the left. Rhombomere locations were assigned on the basis of their positions relative to the otic vesicle (not shown). A and B are composite images of GFP-expressing cells (green) in embryos labeled with an antibody against acetylated tubulin (orange). (A and B) In intact 20 and 28 hpf wild-type embryos, FBMNs (nVII motor neurons) are associated with axons of the ventral longitudinal fascicle (arrowheads) along the entire migratory pathway from rhombomere 4 (r4) to r5, r6 and r7. (C and E) In an intact (control) 18 hpf embryo embedded in agarose (C) and in an 18 hpf hindbrain explant, the FBMNs (nVII, arrowheads) are found in r4 and have just initiated caudal migration. (D and F) In a control 24 hpf embryo (D) and a 24 hpf hindbrain explant (F), several nVII motor neurons have migrated out of r4 into r5 and r6.

Data from several experiments are summarized in Table 1. Deyolked whole embryos or explants cultured in L-15 medium exhibit relatively high levels of cell death (30–40% of embryos) and mortality (25–35% of embryos died). Interestingly, over 95% of hindbrain explants embedded in agarose and overlaid with L-15 medium remain relatively healthy and survive, and only about 15% of explants exhibit increased cell death compared to intact control embryos. Significantly, FBMNs migrated normally into posterior rhombomeres in most hindbrain explants suspended in culture (81%) or embedded in agarose (94%), demonstrating that the process of explanting and culturing hindbrain tissue from 16 hpf embryos does not have any deleterious effect on motor neuron migration during the subsequent 14 h in culture (i.e., up to the equivalent stage of an intact 30 hpf embryo).

Table 1.

Facial branchiomotor neurons (FBMNs) migrate normally in hindbrain explants

| Treatment | Total number of embryos/explantsa | %Surviving at 30 hpf | %With increased cell deathb | %With normal FBMN migration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact control embryo | 45 (5) | 100% | 0% | 100% |

| Deyolked, whole embryo | 42 (5) | 67% (28/42) | 32% (9/28) | 57% (16/28) |

| Hindbrain explant in culture medium | 36 (7) | 75% (27/36) | 41% (11/27) | 81% (22/27) |

| Hindbrain explant embedded in agarose | 36 (8) | 97% (35/36) | 14% (5/35) | 94% (33/35) |

Number of experiments in parentheses.

Cell death was scored by examining embryos/explants under DIC optics and identifying dying cells. Many experimental embryos exhibited higher incidence of dying cells than intact control embryos. Nevertheless, FBMNs migrated normally out of rhombomere 4 into caudal rhombomeres in most of these embryos or explants. In some experiments, embryos were stained with acridine orange to label dying cells (Fig. 4G and H).

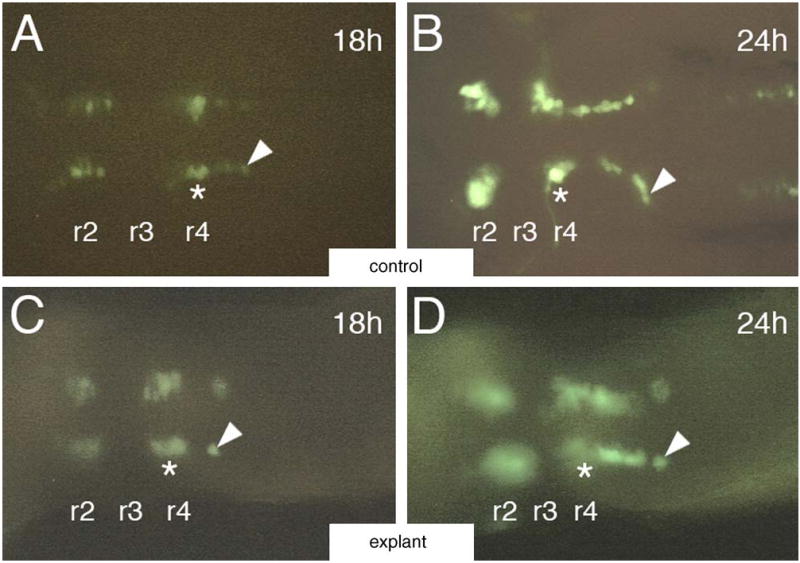

We next examined FBMN migration in GFP-expressing hindbrain explants by time-lapse video microscopy. FBMNs in control embryos migrate normally out of r4 into caudal rhombomeres (Fig. 3A and B; average speed = 19.5 μm/h, n = 10 cells, from Jessen et al., 2002). While FBMNs also migrate out of r4 into caudal rhombomeres in explants (Fig. 3C and D), they move more slowly than controls (average speed = 15 μm/h, n = 3 cells from different explants). Nevertheless, FBMN migration was robust in explants such that nearly all FBMNs migrated out of r4 by 30 hpf in culture (data not shown). However, it is possible that later stages of neuronal migration, such as the lateral migration of FBMN cell bodies within r6 and r7 (Chandrasekhar, 2004) that occurs between 30–48 hpf, are affected in cultured explants.

Fig. 3.

Video microscopy of migrating FBMNs in hindbrain explants. All panels show dorsal views of the hindbrain with anterior to the left. (A and B) In an intact 18 hpf control embryo (A), a GFP-expressing motor neuron (arrowhead) is close to its origin within r4 (asterisk). By 24 hpf (B), the same cell (arrowhead) has migrated more caudally into r6. (C and D) In an 18 hpf hindbrain explant (C), an isolated GFP-expressing motor neuron (arrowhead) is found in r5. By 24 hpf (D), the same cell (arrowhead) has migrated caudally into r6.

3.2. Morphogenesis and patterning are mostly normal in hindbrain explants

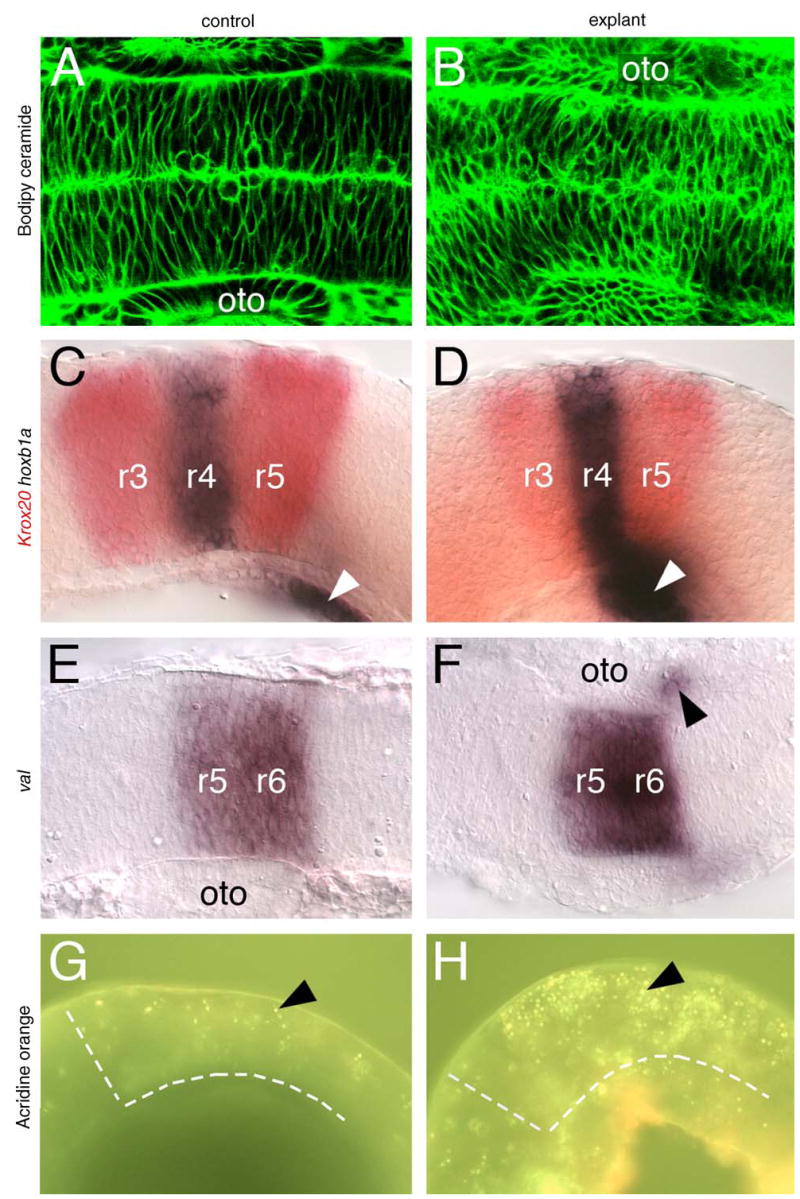

While FBMN migration out of r4 into caudal rhombomeres is not affected in hindbrain explants, we rigorously tested whether other aspects of hindbrain development also occurred normally. Bodipy ceramide labeling of live embryos has been used extensively to monitor cell shapes and organization in the developing zebrafish neural tube (Cooper et al., 1999). The pattern and organization of cells within the neural tube are similar between intact embryos and hindbrain explants (Fig. 4A, B; n = 3 for each), indicating that morphogenesis of the neural tube is unaffected in explants. We next examined the expression of a number of rhombomere-specific genes to monitor positional identities and boundary formation in hindbrain explants. The expression of krox20 (Oxtoby and Jowett, 1993) and hoxb1a (Prince et al., 1998) in rhombomeres 3 and 5 (r3 and r5) and in r4, respectively (Fig. 4C; n = 10) is not affected in explants (Fig. 4D; n = 10). Similarly, the expression of val (Moens et al., 1998) in r5 and r6 is similar between intact embryos (Fig. 4E; n = 8) and hindbrain explants (Fig. 4F; n = 11). Furthermore, val-expressing neural crest cells migrate normally out of r6 in explants (Fig. 4F), and hoxb1a-expressing putative neural crest cells also develop normally in explants (Fig. 4D). These results demonstrate that morphogenesis and patterning occur normally following deyolking and explant culture of the zebrafish hindbrain.

Fig. 4.

Morphogenesis and patterning is mostly normal in hindbrain explants. A, B, E, F show dorsal views, and C, D, G, H show lateral views of the hindbrain, with anterior to the left. (A and B) Bodipy-ceramide (green) labels the interstitial spaces between neuroepithelial cells, and shows that the cell shapes and their organization are comparable between an intact control embryo (A) and a hindbrain explant (B). (C–F) In control embryos, krox20 (red), hoxb1a (C), and val (E) are expressed in characteristic patterns in r3 and r5 (krox20), r4 (hoxb1a), and r5 and r6 (val), respectively. In hindbrain explants (D and F), these rhombomere-specific genes are expressed normally. Neural crest cells expressing val (arrowhead in F) migrate normally out of r6 in explants, and putative neural crest cells expressing hoxb1a (arrowheads in C and D) develop normally in explants. The apparently stronger and more anterior expression of hoxb1a in the explant (D) results from the curling and compression of the explanted tissue following deyolking (see panel H). (G and H) Acridine orange labels a few dying cells (arrowhead) in an intact control embryo (G). In a hindbrain explant (H), the number of dying cells (arrowhead) is significantly higher. The broken white lines in G and H delineate the anterior and ventral margins of the hindbrain. oto: Otocyst.

Since some explants exhibited increased cell death under DIC optics (Table 1), we further examined cell death in explants by acridine orange labeling (Brand et al., 1996; Bingham et al., 2003). While dying hindbrain cells are seen in control embryos at 24 hpf (Fig. 4G; 54 cells per embryo, n = 3), the number of dying cells is much higher in hindbrain explants (Fig. 4H; 127 cells per explant, n = 3), suggesting that the experimental procedures are causing significant additional cell death over control levels. Nevertheless, overall morphological and genetic patterning, and the migration of specific cell types such as neural crest and FBMNs is largely unaffected in hindbrain explants.

3.3. Neurogenesis and axonal patterning occur normally in hindbrain explants

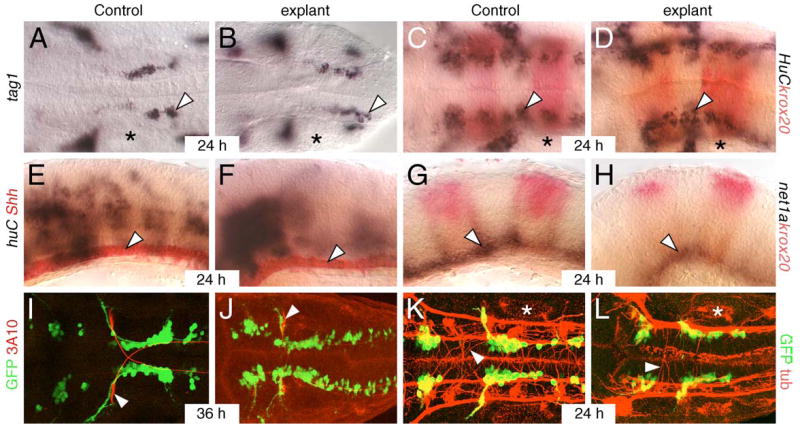

Since there is increased cell death in many hindbrain explants compared to intact embryos, we examined in detail whether neurogenesis and axonogenesis were affected in explants. Zebrafish tag1, which encodes a cell-adhesion molecule (Warren et al., 1999), is expressed in similar fashion in migrating FBMNs in control embryos (Fig. 5A; n = 12) and hindbrain explants (Fig. 5B; n = 9), indicating that motor neurons differentiate normally in explants. The expression pattern of huC, a post-mitotic pan-neuronal marker (Kim et al., 1996; Lyons et al., 2003), is similar between intact embryos (Fig. 5C and E; n = 14) and hindbrain explants (Fig. 5D and F; n = 16), suggesting that neurogenesis occurs normally in explants. Zebrafish sonic hedgehog (shh), which plays an important role in ventral neural tube patterning, including branchiomotor induction (Chandrasekhar et al., 1998; Schauerte et al., 1998; Bingham et al., 2001), is similarly expressed in floor plate cells in intact embryos (Fig. 5E; n = 5) and hindbrain explants (Fig. 5F; n = 8). Consistent with this, trigeminal (nV) and vagal (nX) motor neurons are induced normally in hindbrain explants (Fig. 2E and F; data not shown). Expression of netrin1a (net1a), a Shh-induced axon guidance gene (Lauderdale et al., 1997, 1998), is slightly reduced but still substantial in hindbrain explants (Fig. 5H, n = 7; intact control: Fig. 5G; n = 5), suggesting that axons are patterned normally in explants. We tested this by examining the development of the Mauthner reticulospinal axons using the 3A10 antibody (Hatta, 1992; Fig. 5I; n = 13), and the formation of major axon tracts in the hindbrain using an antibody against acetylated tubulin (Chitnis and Kuwada, 1990; Fig. 5K; n = 8). In hindbrain explants, major axon tracts such as the dorsal and ventral longitudinal fascicles (DLF and VLF) were largely unaffected (Fig. 5L; n = 6), as evidenced by the normal decussation of Mauthner reticulospinal axons in r4, and their extension within the VLF (Fig. 5J; n = 21). These results collectively demonstrate that neurogenesis and axonal patterning are mostly unaffected in hindbrain explants.

Fig. 5.

Neurogenesis and axonal patterning occur normally in hindbrain explants. A–D, and I–L show dorsal views, and E–H show lateral views of the hindbrain with anterior to the left. Asterisks in A–D, K and L mark the otocyst. (A and B) FBMNs (arrowhead) differentiate and migrate normally at 24 hpf in an intact control embryo (A) and a hindbrain explant (B). (C and D) Post-mitotic huC-expressing neurons (arrowhead) are distributed at the lateral margin of rhombomeres 3, 4, and 5 in a similar fashion in an intact control embryo (C) and a hindbrain explant (D). Krox20 expression (red) is evident in r3 and r5. (E and F) Floor plate cells (arrowhead) express shh in a similar manner in an intact control embryo (E) and a hindbrain explant (F). The number of huC-expressing cells is slightly increased in the explant. (G and H) Netrin1a, an axon guidance gene induced by Shh signaling, is expressed (arrowhead) throughout the ventral neural tube in an intact control embryo (G). Net1a expression is intact but slightly reduced in a hindbrain explant (H). (I and J) The Mauthner reticulospinal neurons (red, arrowhead) and their decussating axons exhibit similar morphologies at 36 hpf in an intact control embryo (I) and a hindbrain explant (J). (K and L) An antibody against acetylated tubulin labels longitudinal axon fasicles (red) and individual reticulospinal axons (arrowhead) in a similar fashion in an intact control embryo, and a hindbrain explant. Longitudinal axon fasicles on one side appear fused in the explant due to tilting of the tissue. GFP-expressing FBMNs migrate normally in explants (J and L) in a similar fashion to intact embryos (I and K).

4. Discussion

The transparent zebrafish embryo is an excellent system for examining dynamic processes such as cell motility in vivo. However, the large yolk cell and embryonic movements impair our ability to image such processes efficiently, in particular the tangential migration of facial branchiomotor neurons (FBMNs) in the hindbrain. We demonstrate here that zebrafish explant culture (Langenberg et al., 2003), which eliminates the yolk cell and movements of the embryo, can be used effectively to study FBMN migration. In explants, FBMNs migrate normally out of rhombomere 4 (r4) into caudal rhombomeres (r5, r6 and r7), although they move slightly slower than in vivo, and subsequent lateral migration within r6 and r7 may be affected. Importantly, several hallmarks of development such as hindbrain segmentation, neurogenesis, cell migrations and rearrangements, and axonal patterning are largely unaffected in explants. These results demonstrate that studies of FBMN migration in cultured hindbrain explants can be an important complement to in vivo analysis in intact embryos.

Our principal goals in adapting the explant technique (Langenberg et al., 2003) for studying FBMN migration were to ensure the health of the explanted hindbrain tissue, and to rigorously test whether FBMN migration and hindbrain development proceeded normally in these tissues. Since explants were prepared from 16 hpf embryos in order to study the early stages of FBMN migration, analysis of developmental markers was carried out at 24–30 hpf and at 36 hpf. Our results show that development of the explanted tissue is completely normal for the first 12–14 h in culture (i.e., until 28–30 hpf in intact embryos) (Figs. 2, 4 and 5). However, at 36 hpf, the expression of interneuron markers evx1 (Thaeron et al., 2000) and zn5 (Trevarrow et al., 1990) was variably reduced in explants (data not shown), suggesting that particular aspects of hindbrain development may not occur normally beyond 12–14 h of explant culture. Moreover, there was about a 2.5-fold increase in cell death at 24 hpf in some explants compared to intact embryos (Fig. 4). Despite these indications, explants maintained a healthy appearance for 36 h in culture (data not shown), the number of GFP-expressing branchiomotor neurons continued to increase (data not shown), and FBMNs born during explant culture migrated normally out of r4 into caudal rhombomeres (Figs. 2, 4 and 5). Therefore, we are convinced that hindbrain development and FBMN migration occur essentially normally during the first 12–14 h of explant culture (equivalent to 28–30 hpf in vivo). Given that a majority of FBMNs are born in r4 and migrate into r6 and r7 by 30 hpf (Chandrasekhar et al., 1997; Higashijima et al., 2000), hindbrain explant culture represents an excellent preparation for studying FBMN migration.

Our observations thus far indicate that FBMNs in explants migrate at ~25% lower speeds than in vivo (Fig. 3). Other aspects of migratory behavior appear not to be affected (data not shown), but extensive studies, incorporating more technical modifications, will be needed to clarify this issue. Furthermore, it may not be feasible to study the lateral migration of FBMNs in r6 and r7 using explant culture. Nevertheless, there are several benefits to producing a reliable explant system. First, hindbrain explants are very thin compared to intact embryos, enabling high-resolution imaging of cell shapes and behaviors during FBMN migration. Next, explant culture may allow for convenient isolation of different branchiomotor neuron populations. Lastly, explant culture will allow us to design perfusion experiments to test the effects of pharmacological reagents on specific aspects of FBMN migration. Since the skin of the zebrafish embryo is impermeable, such experiments are not feasible in intact embryos. The yolk cell may also sequester or act as a reservoir for chemicals, adding to the difficulty of doing these experiments in vivo. Experiments to validate some of these applications of hindbrain explant culture are in progress.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tobias Langenberg and Michael Brand for providing the explant culturing procedure prior to publication. We thank Amy Foerstel, Moe Baccam, and Matthew McClure for excellent fish care. We thank the zebrafish community for providing cDNAs for in situ probes, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa for monoclonal antibodies. This work was supported by an NIH training grant fellowship (NIGMS T32 GM08396 to S.M.B.), awards from the University of Missouri Graduate School and an NSF-REU grant to the University of Missouri (G.T.), and grants from NIH (MBRSRISE 5R25 GM59244 to Barry University (G.T.) and NS40449 to A.C.).

References

- Bingham S, Nasevicius A, Ekker SC, Chandrasekhar A. Sonic hedgehog and tiggy-winkle hedgehog cooperatively induce zebrafish branchiomotor neurons. Genesis. 2001;30:170–4. doi: 10.1002/gene.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham S, Higashijima S, Okamoto H, Chandrasekhar A. The Zebrafish trilobite gene is essential for tangential migration of branchiomotor neurons. Dev Biol. 2002;242:149–60. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham S, Chaudhari S, Vanderlaan G, Itoh M, Chitnis A, Chandrasekhar A. Neurogenic phenotype of mind bomb mutants leads to severe patterning defects in the zebrafish hindbrain. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:451–63. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M, Heisenberg CP, Warga RM, Pelegri F, Karlstrom RO, Beuchle D, et al. Mutations affecting development of the midline and general body shape during zebrafish embryogenesis. Development. 1996;123:129–42. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar A, Moens CB, Warren JT, Jr, Kimmel CB, Kuwada JY. Development of branchiomotor neurons in zebrafish. Development. 1997;124:2633–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar A, Warren JT, Jr, Takahashi K, Schauerte HE, van Eeden FJM, Haffter P, et al. Role of sonic hedgehog in branchiomotor neuron induction in zebrafish. Mech Dev. 1998;76:101–15. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar A. Turning heads: development of vertebrate branchiomotor neurons. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:143–61. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis AB, Kuwada JY. Axonogenesis in the brain of zebrafish embryos. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1892–905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-01892.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha M, Adams R. Oriented cell divisions and cellular morphogenesis in the zebrafish gastrula and neurula: a time-lapse analysis. Development. 1998;125:983–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MS, D’Amico LA, Henry CA. Confocal microscopic analysis of morphogenetic movements. Methods Cell Biol. 1999;59:179–204. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61826-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KL, Leisenring WM, Moens CB. Autonomous and nonautonomous functions for Hox/Pbx in branchiomotor neuron development. Dev Biol. 2003;253:200–13. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, Neuhauss SC, Malicki J, Stemple DL, et al. A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:37–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JS, Myers PZ, Westerfield M. Pathway selection by growth cones of identified motoneurones in live zebra fish embryos. Nature. 1986;320:269–71. doi: 10.1038/320269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garel S, Garcia-Dominguez M, Charnay P. Control of the migratory pathway of facial branchiomotor neurones. Development. 2000;127:5297–307. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour DT, Maischein HM, Nusslein-Volhard C. Migration and function of a glial subtype in the vertebrate peripheral nervous system. Neuron. 2002;34:577–88. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffter P, Granato M, Brand M, Mullins MC, Hammerschmidt M, Kane DA, et al. The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish Danio rerio. Development. 1996;123:1–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta K. Role of the floor plate in axonal patterning in the zebrafish CNS. Neuron. 1992;9:629–42. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90027-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbomel P, Thisse B, Thisse C. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1999;126:3735–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashijima S, Hotta Y, Okamoto H. Visualization of cranial motor neurons in live transgenic zebrafish expressing green fluorescent protein under the control of the islet-1 promoter/enhancer. J Neurosci. 2000;20:206–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00206.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson LD, Chien CB. Pathfinding and error correction by retinal axons: the role of astray/robo2. Neuron. 2002;33:205–17. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen JR, Topczewski J, Bingham S, Sepich DS, Marlow F, Chandrasekhar A, et al. Zebrafish trilobite identifies new roles for Strabismus in gastrulation and neuronal movements. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;8:610–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Ueshima E, Muraoka O, Tanaka H, Yeo SY, Huh TL, et al. Zebrafish elav/HuC homologue as a very early neuronal marker. Neurosci Lett. 1996;216:109–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)13021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster RW, Fraser SE. Direct imaging of in vivo neuronal migration in the developing cerebellum. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1858–63. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00585-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenberg T, Brand M, Cooper MS. Imaging brain development and organogenesis in zebrafish using immobilized embryonic explants. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:464–74. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale JD, Davis NM, Kuwada JY. Axon tracts correlate with netrin-1a expression in the zebrafish embryo. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:293–313. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale JD, Pasquali SK, Fazel R, van Eeden FJM, Schauerte HE, Haffter P, et al. Regulation of netrin-1a expression by hedgehog proteins. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;11:194–205. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons DA, Guy AT, Clarke JD. Monitoring neural progenitor fate through multiple rounds of division in an intact vertebrate brain. Development. 2003;130:3427–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.00569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Rubenstein JL. A long, remarkable journey: tangential migration in the telencephalon. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:780–90. doi: 10.1038/35097509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens CB, Cordes SP, Giorgianni MW, Barsh GS, Kimmel CB. Equivalence in the genetic control of hindbrain segmentation in fish and mouse. Development. 1998;125:381–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxtoby E, Jowett T. Cloning of the zebrafish krox-20 gene (krx-20) and its expression during hindbrain development. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1087–95. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince VE, Joly L, Ekker M, Ho RK. Zebrafish hox genes: genomic organization and modified colinear expression patterns in the trunk. Development. 1998;125:407–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauerte HE, van Eeden FJM, Fricke C, Odenthal J, Strahle U, Haffter P. Sonic hedgehog is not required for the induction of medial floor plate cells in the zebrafish. Development. 1998;125:2983–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer M. Initiation of facial motoneurone migration is dependent on rhombomeres 5 and 6. Development. 2001;128:3707–16. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaeron C, Avaron F, Casane D, Borday V, Thisse B, Thisse C, et al. Zebrafish evx1 is dynamically expressed during embryogenesis in subsets of interneurones, posterior gut and urogenital system. Mech Dev. 2000;99:167–72. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00473-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevarrow B, Marks DL, Kimmel CB. Organization of hindbrain segments in the zebrafish embryo. Neuron. 1990;4:669–79. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90194-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlaan G, Tyurina O, Karlstrom R, Chandrasekhar A. Gli function is essential for motor neuron induction in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warga RM, Kimmel CB. Cell movements during epiboly and gastrulation in zebrafish. Development. 1990;108:569–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JT, Jr, Chandrasekhar A, Kanki JP, Rangarajan R, Furley AJ, Kuwada JY. Molecular cloning and developmental expression of a zebrafish axonal glycoprotein similar to TAG-1. Mech Dev. 1999;80:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon; 1995. p. 250. [Google Scholar]