Abstract

Previous studies have not demonstrated consistent results on the effect of surgical delay on outcome. This study investigated the association between the delay to surgery and the development of postoperative complications, length of hospital stay (LOS) and one-year mortality. Patients that underwent surgery for a hip fracture in a two-year period were included in a retrospective study. Uni- and multivariate regression analysis was performed in 192 hip fracture patients. There was a trend towards fewer postoperative complications (P = 0.064; multivariate regression, MR) and shorter LOS (P = 0.088; MR) in patients with a delay of less than one day to surgery. No association between surgical delay and one-year mortality was found in the population as a whole (P = 0.632; univariate regression, UR). Delay to surgery beyond one day was associated with an increased risk of infectious complications (P = 0.004; MR). In ASA I and II class patients, operation beyond one day from admission was associated with an increased risk of one-year mortality (P = 0.03; MR) and more postoperative infectious complications (P = 0.02; MR). The trends towards fewer complications and shorter LOS suggest that early surgery (within one day from admission) is beneficial for hip fracture patients who are able to undergo an operation.

Résumé

Certaines études n’ont pas mis en évidence de résultats probants à propos de la prise en charge chirurgicale retardée des fractures du col fémoral. Cette étude a pour but de mettre en évidence la relation entre les complications chirurgicales et le délai de la prise en charge, la durée moyenne de séjour (DMS), et la mortalité à un an. Les patients qui ont bénéficié d’une prise en charge chirurgicale pour une fracture de la hanche dans les deux années précédentes ont été inclus dans une étude rétrospective. Une étude avec régression multi variable a été réalisée pour 192 hanches fracturées. Il y a moins de complications post opératoires et une DMS plus courte (P = 0.088) chez les patients dont le délai de prise en charge est inférieur à un jour. Nous n’avons pas retrouvé de relations entre le délai de prise en charge et la mortalité à 1 an. Nous n’avons pas trouvé non plus de relation entre le délai de prise en charge et la mortalité à 1 an. Quand la chirurgie est réalisée plus d’un jour après le traumatisme, le taux de complications infectieuses augmentent (P = 0.004 MR). Chez les patients de classe ASA I et ASA II une prise en charge chirurgicale réalisée au-delà d’un jour après l’entrée dans le service est en relation avec une augmentation du risque de mortalité à 1 an (P = 0.03) et du nombre de complications infectieuses (P = 0.02). En conclusion, nous pouvons affirmer qu’afin de diminuer les complications, de raccourcir la durée moyenne du séjour chez ces patients, il est nécessaire qu’ils bénéficient d’une prise en charge chirurgicale inférieure à 1 jour après leur hospitalisation.

Introduction

Hip fractures represent an increasingly important health care problem. The incidence of hip fracture patients in the Netherlands has increased from 15,286 patients in 1999 to 17,550 patients in 2003, with an expected increase of 5% per year until 2025 [10]. The one-year mortality rate is reported to be between 11 and 34% [4, 7, 11].

There is a non-consistent perception that delay before surgical treatment of hip fracture patients is associated with an increase in postoperative complications [3, 5, 9, 12, 15], length of hospital stay [2, 3, 6, 9, 13] and mortality [1–3, 9, 12, 15]. During analysis of previous studies, adjustment for preoperative health status (ASA class) has not always been performed [1, 2, 4, 6]. Theoretically, relatively healthy patients (ASA I and II class) are operated on sooner than patients who require more preoperative evaluation and preparation.

Recently, it has been stated that early surgery, within 24 hours, is independently associated with a reduced length of hospital stay [9]. In this large prospective study, an association between fewer major postoperative complications and operation within 24 hours was found in a subgroup of healthier patients defined as patients without abnormal clinical findings, aortic stenosis, dementia and end-stage renal disease with dialysis on admission. No association (P = 0.09) with mortality after six months was found. A recent retrospective study in 57,315 patients found an increase in mortality up to one year with a longer delay to surgery. This association was particularly strong in patients younger than 70 years of age with no co-morbidities [14].

The primary aim of this study was to clarify the possible association between delay to surgery with the development of postoperative complications, length of hospital stay and one-year mortality rate. A secondary aim was to perform an identical subanalysis in the restricted cohorts of ASA class 1–2 and ASA class 3–4 patients.

Patients and methods

All medical records of patients above 55 years old that were managed operatively for a hip fracture during a two-year period at our level-1 trauma hospital were reviewed. Polytrauma patients, patients with pathological fractures, a previous fracture or operation on the ipsilateral hip and initial conservative management were excluded.

The following parameters were extracted from the patient surgical and anaesthetic written and computer records: gender, age, pre- and postoperative accommodation (home, retirement home, nursing home), date of admission to the ED, date and time of operation and date of discharge, type of fracture (intra- or extracapsular), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, in-hospital mortality and in-hospital postoperative complications. The latter were divided into infectious (urinary tract infection, pneumonia, wound infection and sepsis) and non-infectious complications [congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, gastro-intestinal haemorrhage, cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and pulmonary embolism].

The one-year mortality was determined by contacting either the general practitioner or the managing staff of the present accommodation of the patient. The delay to surgery was calculated from the day of hospital admission.

A subanalysis was performed in the relatively healthy, defined as ASA I or II class, group of patients to gain insight into the effect of delay to surgery due to health status on morbidity, LOS and mortality.

Statistical analysis

Variables potentially affecting clinical outcome were identified through univariate analysis. Continuous variables were analysed using the Student’s t-test and dichotomous variables through the Chi square test. Variables with significant values after univariate analysis were subsequently analysed in a multivariate model to distinguish the individual effect on outcome.

Dichotomous outcome variables (complications and mortality) were analysed using a binary logistic regression model. Continuous outcome variables (length of stay) were analysed by means of a Cox regression model. Length of stay was log-transformed for the analysis since it was not normally distributed, as determined with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Results were expressed as P values with a 95% confidence interval and odds ratios (OR) for the dichotomous outcome variables. A P-value below 0.05 was considered to be significant. The SPSS 9.0 (Chicago, IL) software package was used.

Results

In the two-year study period, 229 patients were treated operatively for a hip fracture. Thirty-seven patients (16%) met the exclusion criteria listed in the methods section. Three patients (1%) were untraceable and lost to follow-up after one year and were subsequently excluded in the one-year mortality analysis. This left 192 patients eligible for analysis; 111 patients (58%) had sustained an intracapsular fracture and 81 (42%) an extracapsular fracture. Demographics, pre-admission residential status, ASA class and the time to surgery are shown in Table 1. A delay to surgery of less than one day was present in 68% of the patients.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics: demographics, pre-injury residence status, ASA class, time to surgery and implants in the study cohort (n = 192)

| Intracapsular (%) | Extracapsular (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 111 (58) | 81 (42) | 192 |

| Age | 78.8 (SEM 1.06) | 82.6 (SEM 1.06) | 80.4 (SEM 0.77) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 27 (24) | 18 (22) | 45 (23) |

| Female | 84 (76) | 63 (78) | 147 (77) |

| Admitted from | |||

| Home | 74 (67) | 46 (57) | 120 (63) |

| Retirement home | 23 (21) | 18 (22) | 41 (21) |

| Nursing home | 14 (13) | 17 (21) | 31 (16) |

| ASA class | |||

| I | 17 (15) | 9 (11) | 26 (14) |

| II | 50 (46) | 39 (48) | 89 (46) |

| III | 41 (37) | 29 (36) | 70 (37) |

| IV | 3 (3) | 4 (5) | 7 (4) |

| Days admission to operation | |||

| 1 | 72 (65) | 58 (72) | 130 (68) |

| 2 | 29 (26) | 20 (25) | 49 (26) |

| ≥3 | 10 (9) | 3 (4) | 13 (7) |

SEM = standard error of the mean

Postoperative complications developed in 39 (20%) patients; infectious and non-infectious complications are shown separately in Table 2. Similar complication rates were seen for intra- and extracapsular fracture patient groups.

Table 2.

Postoperative complications, LOS, discharge status and mortality of the study cohort (n = 192)

| Intracapsular [n = 111 (%)] | Extracapsular [n = 81 (%)] | Total [n = 192 (%)] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | |||

| 0 | 91 (82) | 62 (77) | 153 (80) |

| 1 | 12 (11) | 15 (19) | 27 (14) |

| >2 | 8 (7) | 4 (5) | 12 (6) |

| Infectious complications | |||

| Urinary tract Infection | 7 (6) | 8 (10) | 15 (8) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 3 (2) |

| Wound infection | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Sepsis | - | 2 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Other complications | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 6 (5) | 4 (5) | 10 (5) |

| Arrhythmia | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 6 (3) |

| CVA | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Gastro-intestinal bleeding | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Length of stay (days) | 17.5 (SEM 1.58) | 16.4 (SEM 1.90) | 17 (SEM 1.21) |

| Discharged to | |||

| Home | 39 (37) | 19 (25) | 58 (32) |

| Retirement home | 28 (27) | 26 (35) | 54 (30) |

| Nursing home | 38 (36) | 30 (40) | 68 (38) |

| Discharged to initial residence | |||

| Yes | 42 (40) | 31 (41) | 73 (41) |

| No | 63 (60) | 44 (59) | 107 (59) |

| Mortality (in-hospital) | 6 (5) | 6 (7) | 12 (6) |

| Mortality (1 year)a | 23 (21)a | 24 (30)a | 47 (25)a |

a n = 189

SEM = standard error of the mean

In the total cohort, 41% of the surviving patients could be discharged to their original accommodation. Of patients originally living at home, 22% were discharged to a retirement home and 27% to a nursing home. Of patients originally living in a retirement home, 73% were able to return, and the remainder was discharged to a nursing home. Of all patients admitted from a nursing home, 93% were able to return there, and 7% were transferred to a retirement home.

Twelve patients (6%) died in the hospital, and the mortality increased to 47 patients (25%) after one year. Similar mortality was noted in both the intra- and extracapsular fracture patients.

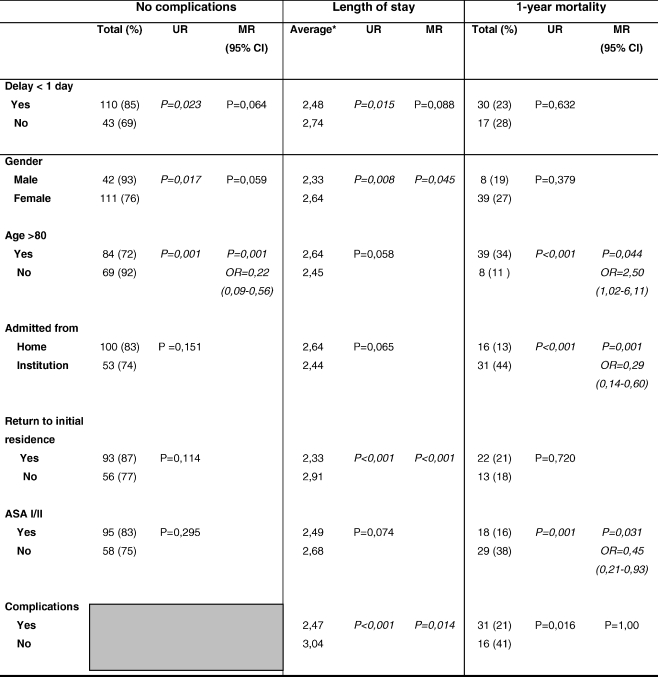

In the multivariate regression analysis, an associative trend could be identified between longer delay to surgery and the development of postoperative complications; age higher than 80 was identified as the only independent risk factor for complications (Table 3). In the infectious complications subgroup, a delay to surgery beyond one day from admission to operation was a significant factor [P = 0.004; OR=0.24 (95% CI: 0.09–0.64), not shown].

Table 3.

Uni- and multivariate regression analysis of the association between delay to surgery, patient characteristics and the dependent outcomes of postoperative complications (n = 192), length of stay (n = 180) and 1-year mortality (n = 189)

UR = univariate regression, MR = multivariate regression, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * log-transformed (no OR or CI calculation given)

The trend towards more postoperative complications consequently led to a similar trend towards a longer length of stay (LOS) in patients with longer delay to surgery in the multivariate regression analysis of survivors. Discharge to a different residence, the development of postoperative complications and female gender were significantly associated with a longer LOS. An independent factor leading to a higher postoperative morbidity rate was age over 80 years. Independent factors leading to longer LOS were: the development of complications, discharge to residential/nursing home and female gender.

Univariate regression analysis showed no association between the delay to surgery and one-year mortality. Independent factors associated with one-year mortality in the multivariate regression analysis were: admission from a retirement or nursing home, ASA 3–4 class and age over 80 years. In the restricted cohort of ASA 1–2 class patients, the multivariate analysis showed no significant association between a delay to surgery and the development of postoperative complications and LOS (Table 4). However, a longer delay from admission to operation did have an independent effect on one-year mortality. Furthermore, delayed operation was a significant factor on the development of infectious complications [P = 0.018; OR=7.1 (95% CI: 1.4–33.3), not shown]. In the cohort of ASA 3–4 class patients, complications, LOS and one-year mortality were unaffected by surgical delay beyond one day.

Table 4.

Analysis of the operative delay divided in ASA 1–2 class (n = 115) and ASA 3–4 class patients (n = 77)

| Delay | No complications | Length of staya | 1-year mortalityb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UR | MR | UR | MR | UR | MR | ||

| ASA I/II | Admission to | P = 0.018 | P = 0.200 | P = 0.025 | P = 0.346 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.031 |

| operation < 1 day | OR 0.25 (0.07–0.88) | ||||||

| ASA III/IV | Admission to | P = 0.643 | P = 0.350 | P = 0.061 | |||

| operation <1 day | |||||||

an = 180 (hospital survivors)

bn = 189

UR = univariate regression; MR = multivariate regression; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval

Discussion

This retrospective study confirms the trend towards more morbidity and a longer length of hospital stay if surgery for hip fracture patients was delayed beyond one calendar day from admission. This is consistent with a recent prospective study (n = 1,178) with a similar research population that found a decreased length of hospital stay in patients with early surgery (<24 hours) [9]. In a restricted cohort of patients eligible for early treatment (not needing pre-operative investigation), surgery within 24 hours was associated with less morbidity. Another prospective study (n = 3,628) that excluded patients who were delayed for medical reasons, patients with early surgery (<48 hours) had a shorter length of hospital stay [13]. Also consistently, a retrospective study that stratified patients in three groups based on the operative delay (<24, 24 to 72 and >72 hours) found an increase in morbidity as the delay to surgery increased [12].

These findings, however, are hampered by studies with a variety of inclusion criteria and definitions for early surgery (ranging from longer than six h to over four days), which have found conflicting results [3, 5, 8, 13, 15]. In a recent prospective study (n = 2,660), a delay of up to four days to surgery was not associated with morbidity or length of hospital stay in patients that were declared fit for surgery by an anaesthesist [8]. This assessment was performed by different anaesthesists, and no pre-defined criteria such as ASA class were applied. A prospective study of a restricted cohort of elderly patients (n = 367) who were cognitively intact, able to walk and living at home before the hip fracture occurred found no effect of operative delay (>48 hours) on morbidity [15].

The association of delay to surgery and mortality is also the subject of debate. Some prospective and retrospective reports concluded that the time to surgery had no independent association with one-year mortality [5, 8, 9, 13]. Conversely, other studies with adjustment for age, gender and co-morbidity did demonstrate that delayed surgery beyond two days from admission increased the six-month and one-year mortality rates [3, 12, 15]. A recent retrospective multicentre study (n = 57,315) found an independent association between surgical delay (>24 hours) and mortality; in healthier and younger patients, the mortality risk was greater [14].

In our study, the time to surgery had no association with one-year mortality in the study population as a whole. However, multivariate subanalysis showed that healthier ASA class 1–2 patients had significantly less risk for one-year mortality if operated on within one day of admission. In ASA 3–4 class patients, one-year mortality was unaffected by surgical delay beyond one day. In these patients, as opposed to healthier ASA 1–2 patients, the delay is more likely due to the time required for preoperative evaluation and preparation. The ASA 3–4 class patients may therefore have been operated on in better medical condition, which may have counterbalanced the possible deleterious effect of delay to surgery.

In conclusion, a delay of one day from the time of admission to surgery is likely to be associated with the development of postoperative complications (specifically infectious complications) and length of stay. In a subanalysis, ASA class 1–2 patients had a significantly increased risk of one-year mortality and more postoperative infectious complications if operated on beyond one day of admission. Age over 80 years and ASA class both had stronger associations with the clinical outcomes than time to surgery. In view of these results, we recommend that hip fracture patients who are able to undergo surgery are more likely to benefit from surgical treatment within one day of admission.

References

- 1.Casaletto JA, Gatt R (2004) Post-operative mortality related to waiting time for hip fracture surgery. Injury 35:114–120 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Clague JE, Craddock E, Andrew G (2002) Predictors of outcome following hip fracture. Admission time predicts length of stay and in-hospital mortality. Injury 33:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Dorotka R, Schoechtner H, Buchinger W (2003) The influence of immediate surgical treatment of proximal femoral fractures on mortality and quality of life; operation within 6 hours of the fracture versus later than 6 hours. J Bone Jt Surg (Br) 85:1107–1113 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Elliot J, Beringer T, Kee F (2003) Predicting survival after treatment for fracture of the proximal femur and the effect of delays in surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 56:788–795 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Grimes JP, Gregory PM, Noveck H (2002) The effects of time-to-surgery on mortality and morbidity in patients following hip fracture. Am J Med 112:702–709 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kitamura S, Hasegawi Y, Suzuki S (1998) Functional outcome after hip fracture in Japan. Clin Orthop 348:29–36 [PubMed]

- 7.Lawrence VA, Hilsenbeck SG, Noveck H (2002) Medical complications and outcome after hip fracture repair. Arch Intern Med 162:2053–2057 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Moran CG, Wenn RT, Sikand M, Taylor AM (2005) Early mortality after hip fracture: is delay before surgery important? J Bone Jt Surg 87:483–489 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Orosz GM, Magaziner J, Hannan El (2004) Association of timing of surgery for hip fracture and patient outcomes. JAMA 291:1738–1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Prismant. Prismant information products. Hospital statistics. [cited 15 february 2006] Available from: http://www.prismant.nl.

- 11.Richmond J, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD (2003) Mortality risk after hip fracture. J Orthop Trauma 17:53–56 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Keller MS (1995) Early fixation reduces morbidity and mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures from low-impact falls. J Trauma 39:261–265 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Siegmeth AW, Gurusamy K, Parker MJ (2005) Delay to surgery prolongs hospital stay in patients with fractures of the proximal femur. J Bone Jt Surg (Br) 87:1123–1126 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Weller I, Wai EK, Jaglal S et al (2005) The effect of hospital type and surgical delay on mortality after surgery for hip fracture. J Bone Jt Surg (Br) 87:361–366 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Zuckerman JD, Skovrin ML, Koval KJ (1995) Postoperative complications and mortality associated with operative delay in older patients who have a fracture of the hip. J Bone Jt Surg (Am) 77:1551–1556 [DOI] [PubMed]