Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine and predict the time trend of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after total hip replacement (THR). A total of 383 patients receiving primary THR at two medical centers in Taiwan during 1997 to 2000 were enrolled for the study. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by using physician-rated Harris hip score and patient-reported short-form 36-item health survey (SF-36) immediately before the surgery and at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 60 months after surgery. Data analysed by piecewise linear regression revealed remarkable improvements in HRQoL dimensions at the third month after surgery and kept improving until the threshold level of from 39 months to 81 months, at which it reached a plateau. Role limitations due to physical and emotional problems and social functioning after surgery saw the most remarkable improvements, which appear to be related to improvements in functioning in many other dimensions of health. Such interdependence of the dimensions should be examined carefully to see if improvements in social roles can help improve the overall HRQoL in a more effective manner. The results should be applicable to other hospitals in Taiwan and in other countries with similar social and cultural practices.

Résumé

L’objectif de ce travail était d’examiner l’évolution de la qualité de vie après une prothèse totale de hanche par l’étude d’un groupe de 383 patients opérés dans 2 centres de Taiwan entre 1997 et 2000. Des interview ont été menés par des médecins utilisant le score de Harris et le score SF-36 juste après la chirurgie puis à 3, 6, 12, 24 et 60 mois d’évolution. L’analyse en régression linéaire montrait une augmentation notable de la qualité de vie au troisième mois et progressant jusqu’à un plateau atteint entre 39 à 81 mois. Les aspects physique, émotionnel et social étaient les plus améliorés en relation avec l’amélioration d’autres paramètres de santé. Une telle interdépendance doit être examinée soigneusement pour voir si l’amélioration de l’aspect social peut améliorer l’ensemble de la qualité de vie de façon effective. Les résultats peuvent être étendus à d’autres populations de même pratiques culturelles et sociales.

Introduction

The importance of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has been recognised as a principal outcome of total hip replacement (THR) [2, 12]. Studies have also shown substantial improvements in HRQoL after THR surgery [3, 9]. There are two general approaches in the measurement of HRQoL: disease-specific and generic instruments [9, 13]. Disease-specific instruments are administered in longitudinal studies or clinical trials to detect progressive changes after medical or surgical interventions, especially focusing on the improvement in pain relief and physical functioning [1]. The Harris hip score (HHS) is a commonly used physician assessment of physical functioning and pain relief on clinical sites [6]. In contrast to disease-specific measures, generic health instruments are designed for applications across a wide rage of diseases, medical treatments or interventions and are intended to obtain an overall evaluation of health outcomes [5, 13]. The short-form 36-item health survey (SF-36) is a commonly used general health-related instrument and has been shown to be useful in outcome assessments [11].

Despite significant improvement in our understanding of the health effect of THR, many of the previous studies have suffered from some significant shortcomings. First, only a few used longitudinal data with more than two time points. Second, most of the studies used data collected in the USA or in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Finally, when longitudinal data have been used, appropriate statistical methodology has not been applied to control for right censoring and inter-correlations created by repeated measures.

The objectives of this study are threefold. First, to examine the longitudinal changes in each of the dimensions of HRQoL over time, starting with the pre-surgery situation. Second, to predict the mean values of each of the dimensions of HRQoL for THR patients by using appropriate statistical methods. Third, to compare the performance of each of the dimensions of HRQoL over time with the average quality of life for the general population in Taiwan.

Methods

Study design and sample

Data for this study were obtained through a longitudinal observation of THR patients. The longitudinal study was conducted by a THR research team, which consisted of members from two medical centres located in southern Taiwan. To evaluate the changes in HRQoL, a prospective cohort study was designed. From March 1997 to December 2000, all patients receiving primary THR (ICD-9-CM procedure code 8151) from three orthopaedic surgeons working in the two hospitals constituted the population. All THR procedures resulting from traffic accidents, or procedures performed on cognitively impaired patients, were excluded. If patients went through bilateral THR procedures at different times, we chose the latest one as the intervention of interest.

Over the time frame of the study, a total of 383 subjects were found to be eligible and were interviewed pre- and postoperatively. Fifteen subjects died during the 5-year follow-up, and a number of subjects dropped out of the study due to loss of contact (change of address) or refusal to participate. In total, 139 subjects successfully completed the preoperative and five postoperative assessments in this study. Successfully completed response rates were as follows: for 3-month follow-up, 92%; 6-month, 90%; 1-year, 84%; 2-year, 65%; and 5-year, 58%. Table 1 shows the number of subjects at baseline and at different follow-up intervals.

Table 1.

Number of subjects at baseline and at different follow-up intervals

| Items | Baseline | Third month | Sixth month | First year | Second year | Fifth year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of observations | 383 | 383 | 383 | 383 | 383 | 383 |

| Subjects lost to the study | ||||||

| Total | 0 | 30 | 40 | 61 | 133 | 161 |

| Lost to the studya | 0 | 28 | 37 | 59 | 130 | 156 |

| Death | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Available observationsb | 383 | 353 | 343 | 322 | 250 | 222 |

| Observations completed | 383 | 353 | 342 | 304 | 232 | 139 |

| Response rate | 100% | 92% | 90% | 84% | 65% | 58% |

aNumber of subjects lost to the study due to lost contact and/or did not conform to the timing of the survey

bNumber of subjects observed at different time points

Instruments and measurements

Two approaches of HRQoL outcome assessment were used in this study: the modified HHS and the SF-36. The total HHS value ranges from 0 points to 100 points, and the domains include pain function, physical function, deformity, and motion. Pain and physical functions are the two basic considerations and receive the highest weightings in HHS calculations (44 points and 46 points, respectively). Range of motion (ROM) and deformity are not of primary importance. Thus, each receives 5 points in the weighting scheme. This study selected pain and physical functions of HHS for primary analyses. In general, an HHS value below 70 points is considered an indication of poor outcome, while 70 to 80 is considered fair, 80 to 90 good, and 90 to 100 excellent.

The SF-36 is used to measure generic HRQoL [17]. It consists of 36 items, representing physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical functioning (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health perceptions (GH), vitality (energy/fatigue) (VT), social functioning (SF), role limitations due to emotional functioning (RE), and general mental health perceptions (MH). Each subscale of the SF-36 is transformed into a 0–100 scale, with higher score implying a better HRQoL.

Approval to conduct the survey on human subjects was obtained from the institutions involved, before the initiation of the survey. For this study, the HHS surveys were conducted by the orthopaedic surgeons before and after the surgery, while SF-36 health surveys were conducted by trained research assistants.

Statistical analysis

The unit of analysis in this study is the individual THR patient. To compare the overall physical and mental functioning of the study population with the general population of Taiwan, physical component summary (PCS) scores and mental component summary (MCS) scores were calculated by norm-based scoring methods [16]. By the approach followed by a previous study [15], the PCS and MCS scores were computed in comparison with the general population of Taiwan (average value for general population is normalised at 50).

The generalised estimating equations (GEEs) approach was employed to interpret as modelling change the scores calculated per time interval. The advantage of using GEEs in describing longitudinal changes is that they can be used even when patients have unequal numbers of observations or unequal time intervals between the observations [4].

After the operation, a number of health outcomes are likely to improve, but, once a threshold is reached, further progress may be much slower or completely absent. Since the mean value of each of the outcomes may increase at different rates over time, our study adopted a “piecewise linear regression” model allowing discontinuities in the functions and different rates of improvements over the months. Furthermore, since the health outcome variables cannot keep on improving over a longer period of time, a quadratic time variable was introduced in the equation [18]. If the value of threshold time level is represented by X*, the equation to be estimated becomes:

|

Where Yij is the mean value for ith individual, jth subscale of HHS and SF-36,

Xt is the time variable indicating the number of months elapsed after surgery,

Xj* is the threshold level of time for jth subscale of HHS and SF-36,

|

Note that Xj* is not known but can be estimated through empirical analysis.

Table 2 reports the actual mean values and standard errors of HHS and SF-36 subscales for THR patients. The table indicates that HHS and SF-36 subscales increase linearly over time and that the threshold time point appears to be at the 3rd month of the observations; after this time, the scores still show improving trend but at a much lower rate than before.

Table 2.

The mean value and standard error of HHS and SF-36 subscales for THR patients at each of the time points

| Parameter | Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative (n = 383) | Third month (n = 353) | Sixth month (n = 343) | First year (n = 322) | Second year (n = 250) | Fifth year (n = 222) | |

| HHS subscale: mean ± standard error | ||||||

| Pain | 18.07 ± 8.40 | 40.31 ± 4.12 | 41.32 ± 3.12 | 42.05 ± 2.87 | 42.07 ± 3.12 | 41.91 ± 3.25 |

| Physical | 22.10 ± 8.98 | 33.13 ± 7.68 | 37.43 ± 6.84 | 40.73 ± 4.89 | 41.23 ± 5.89 | 41.15 ± 6.91 |

| Total | 46.79 ± 15.3 | 82.78 ± 10.3 | 88.23 ± 9.07 | 92.50 ± 6.71 | 93.05 ± 8.37 | 92.87 ± 8.67 |

| SF-36 subscale: mean ± standard error | ||||||

| PF | 41.51 ± 21.1 | 62.62 ± 23.3 | 71.51 ± 21.1 | 79.60 ± 21.9 | 82.28 ± 23.7 | 85.43 ± 20.1 |

| RP | 14.10 ± 29.8 | 41.11 ± 37.6 | 51.81 ± 39.9 | 68.26 ± 37.7 | 78.88 ± 36.3 | 87.60 ± 31.9 |

| BP | 44.55 ± 9.53 | 48.19 ± 8.23 | 49.59 ± 8.49 | 49.68 ± 6.37 | 50.69 ± 6.41 | 50.14 ± 4.41 |

| GH | 52.32 ± 19.8 | 64.17 ± 18.4 | 67.05 ± 17.6 | 68.55 ± 18.1 | 74.86 ± 20.7 | 75.06 ± 19.8 |

| VT | 59.41 ± 18.6 | 68.79 ± 16.5 | 70.33 ± 15.8 | 72.94 ± 15.2 | 73.17 ± 19.2 | 78.47 ± 19.84 |

| SF | 50.45 ± 23.7 | 66.80 ± 19.2 | 74.46 ± 17.0 | 81.21 ± 15.4 | 88.63 ± 17.4 | 91.07 ± 16.1 |

| RE | 38.38 ± 44.0 | 74.15 ± 37.6 | 84.25 ± 31.8 | 88.49 ± 29.5 | 88.51 ± 29.6 | 90.08 ± 27.3 |

| MH | 66.13 ± 15.8 | 73.54 ± 18.4 | 75.35 ± 13.3 | 75.43 ± 13.2 | 76.60 ± 16.8 | 80.60 ± 17.3 |

| PCS | 24.13 ± 0.51 | 31.50 ± 0.69 | 34.82 ± 0.71 | 38.47 ± 0.75 | 40.92 ± 0.79 | 44.01 ± 0.60 |

| MCS | 47.43 ± 0.60 | 54.31 ± 0.73 | 55.54 ± 0.74 | 55.71 ± 0.72 | 56.30 ± 0.82 | 60.13 ± 0.85 |

Results

Descriptive statistics

Approximately 58% of national THR population were male, and the mean age of the THR population was 58 (SD=14.73) years. For the study sample, at baseline, approximately 56% were male, and the mean age was 59 (SD=14.67) years. In national data, 49% of THR patients had the principal diagnoses of osteoarthritis (OA) and another 40% had avascular necrosis (AVN). For the study population, the percentages were 52% and 39%, respectively. Therefore, the study sample is comparable to the national THR population in terms of demographics and THR diagnoses.

Results of the GEE model

The GEE approach was used to determine whether the dimensions of HRQoL changed over time after surgery. Since this method accounts for possible correlations in repeated measures, unbiased estimate of time trend can be obtained. For the dimension of pain in HHS, the regression coefficient for the time variable was 14.87 [95% confidence interval (95% CI) 14.18, 15.58] and the coefficient for square of time was −2.43 (95% CI −2.55, −2.31) for time period from baseline to threshold. Beyond the threshold, the regression coefficient for the time variable in the pain function was 0.1080 and −0.0014 for the square of time. The pain function improved significantly in the first 3 months after the surgery and kept improving until 38.6 months. Beyond the 39th month after surgery, pain functioning showed a negative trend.

Similarly, the highest levels in physical function score and total score were achieved 39.9 months and 39.4 months, respectively, after the surgery. For SF-36, the maximum values in terms of physical functioning, role related to physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role related to emotional well being, and mental health scores were reached at 67.3 months, 81.4 months, 69.2 months, 79.5 months, 69.6 months, 78.4 months, 63.7 months, and 73.4 months, respectively, after surgery.

The PCS dramatically improved from preoperative level of approximately 24 to about 44 at the end of the 5th year after surgery. At the same time, the MCS also showed remarkable improvement, from approximately 47 to 60. It should be noted that the PCS had a very low average score immediately before the surgery but the gap between the PCS and the norm became lower and lower over the months after surgery. In contrast, MCS showed better than the norm value immediately after the surgery and then kept improving throughout 5 years. The predicted mean values of each dimension of HRQoL for THR patients by piecewise linear regression method are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The predicted mean value of HHS and SF-36 subscales for THR patients by piecewise linear regression method

| Parameter | Pre-operative | Third month | Sixth month | 12th month | 24th month | 60th month | 72rd month | 84th month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHS subscale | ||||||||

| Pain | 18.32 | 41.05 | 41.34 | 41.84 | 42.52 | 42.13 | 41.17 | 39.83 |

| Physical | 22.32 | 36.67 | 37.79 | 39.76 | 42.55 | 41.73 | 39.40 | 37.53 |

| Total | 47.29 | 87.18 | 88.67 | 91.25 | 94.89 | 93.58 | 89.08 | 85.54 |

| SF-36 subscale | ||||||||

| PF | 41.98 | 71.06 | 73.51 | 78.04 | 85.68 | 91.18 | 89.21 | 87.33 |

| RP | 14.50 | 47.53 | 53.93 | 65.38 | 82.94 | 92.89 | 94.81 | 93.99 |

| BP | 44.58 | 49.12 | 49.17 | 49.26 | 49.42 | 49.68 | 49.59 | 48.66 |

| GH | 51.77 | 66.17 | 66.93 | 68.47 | 71.58 | 81.34 | 82.65 | 75.69 |

| VT | 58.65 | 70.84 | 71.10 | 71.77 | 73.71 | 84.29 | 79.54 | 76.29 |

| SF | 47.65 | 69.69 | 72.84 | 78.50 | 87.24 | 92.84 | 94.76 | 92.04 |

| RE | 37.24 | 85.09 | 85.96 | 87.58 | 90.27 | 94.11 | 91.53 | 90.80 |

| MH | 65.25 | 75.38 | 75.39 | 75.57 | 76.58 | 84.92 | 84.99 | 83.27 |

| PCS | 24.16 | 31.59 | 34.10 | 38.23 | 40.53 | 44.29 | 46.11 | 45.90 |

| MCS | 47.43 | 54.31 | 55.53 | 55.79 | 56.39 | 60.21 | 64.40 | 58.01 |

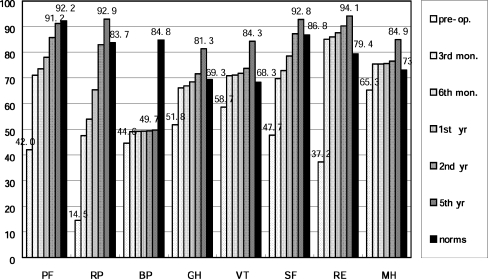

In order to indicate the improvements in each of the subscales of SF-36 for THR patients, again the mean values for general population of Taiwan were used for comparative purposes (n = 18,142) (Fig. 1). The THR patients appear to have considerably better scores for vitality and mental health at the 3rd month after surgery than the norms. Bodily pain (mean = 44.6) was the only subscale that was lower than the norm for the survey population. From the 3rd month to the 5th year after surgery, all subscales, excepting the bodily pain, improved consistently to become similar to or better than the norms.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of SF-36 subscale with the norms at different time points

Discussion

To focus on the time trend of quality of life after surgery, survey information was analysed by the piecewise linear regression method. The significance of the differences between the trends of recovery proportion of each of the dimensions of HRQoL was examined using the GEE approach separately. The regression models indicate that the performance in all dimensions of HRQoL improved remarkably at the 3rd month after surgery and kept improving until the threshold level of from 39 months to 81 months, at which it reached a plateau. Pacault-Legendre and Courpied [10] pointed out that using standard quality of life questions to evaluate patient’s subjective assessment could be problematic. They also found feelings of frustration among patients during the first 3 months after the operation. In this study, quality of life questions posed to patients have been supplemented by physician-rated HHSs, and the inclusion of the physician-rated part should improve the assessment of patient’s health and well being. Moreover, a longer follow-up period was designed for this study to ensure that the observations can indicate the length and severity of short-term temporary frustrations or loss of subjective well being, if any.

Standard guidelines [8] assume that a total score of HHS that reaches 90 points or more indicates a successful THR. The mean HHS of THR patients in the sample was 92.64 at the 1st year after surgery. Pain function score showed the most remarkable improvement, immediately after surgery, and then reach a plateau in approximately 5 years. Physical function score improved substantially from preoperative to the 1st year after surgery and then remained stable over the follow-up period.

For SF-36 subscales, role limitations due to physical and emotional problems were two of the eight subscales that showed the best performance at the 5th year after surgery (mean scores = 92.89 and 94.11, respectively). Before THR surgery, the mean scores for role limitations due to physical and emotional problems were relatively low compared with the other six subscales, which may be due to the fact that individuals with limited physical and emotional functions also face severe role function limitations. Therefore, once the physical and emotional limitation problems were reduced or eliminated by the THR surgery, patients could resume their role functioning. It is also possible that direct interventions to reduce role limitations due to physical and emotional problems help patients enhance their physical and social functioning, which, in turn, help achieve a higher level HRQoL in all dimensions.

Remarkable improvements observed during the first 3 months after surgery for most subscales of SF-36 is consistent with other prior studies [2, 7]. The study also found that role limitation due to physical problems, and physical and social functioning, improved remarkably, not only from the 3rd month to the 1st year after surgery but also afterwards. The results indicate that bodily pain scores have the poorest performance among all subscales throughout the 5-year follow-up period.

Compared with that of the general population, the study sample had very low overall physical functioning score, as indicated by the PCS. Patients reported substantial limitations in self-care and physical and role activities, frequent tiredness, higher degree of bodily pain and poor health in general. In contrast, overall mental functioning of the patients in the study (as demonstrated by MCS) was found to be better than the overall physical functioning score. One of the reasons could be that the overall physical functioning takes more time for full recovery after surgery than mental functioning [8]. This finding appears to support the idea that mental functioning score is more sensitive and specific to THR outcomes than the physical functioning score [14].

The HRQoL data provide relevant health outcome-related information to health professionals and may be used as the yardstick to evaluate the health interventions and development of the recommended standard of care. Most health outcome studies are based on data obtained from physician-based or hospital-based patient cohorts. Such a sampling procedure produces a biased sample, due to self-selection of patients. This study investigated all patients from two major medical centers and avoided using one orthopaedic surgeon.

Conclusions

Data analysed by piecewise linear regression revealed remarkable improvements in HRQoL dimensions at the 3rd month after surgery and kept improving until the threshold level of 4 to 7 years, indicating that the change trend is varied for performance of HRQoL dimensions. This study also found that role limitations and social functioning are closely linked with physical and mental functioning of patients. Although no causal direction is known, it will be useful to examine the potential effects of improved role playing and social functioning on physical health status of patients. The study also shows that the MCS of THR patients improves rapidly after surgery and becomes higher than the average score for the general population of Taiwan. Clearly, the surgery itself improves health situation of patients, and it appears that patients remain in a state of mental anxiety before the surgery. Although the MCS improves rapidly for THR patients, the PCS of THR patients tends to be no better than the norm. In fact, since the THR patients are older than the general population, achieving the average PCS norm again indicates effectiveness of the surgery in terms of its impact on the quality of life and overall health status. Therefore, the results should be applicable to other hospitals in Taiwan and in other countries with similar social and cultural practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ted Chen and Dr. Gene Beyt for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This study was supported by a grant from the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC92-2320-B-037-055).

References

- 1.Bruce B, Fries J (2004) Longitudinal comparison of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC). Arthritis Rheum 51:730–737 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY (2004) Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86:963–974 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Fitzgerald JD, Orav EJ, Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Poss R, Goldman L, Mangione CM (2004) Patient quality of life during the 12 months following joint replacement surgery. Arthritis Rheum 51:100–109 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hardin JW, Hilbe JM (2003) Generalized estimating equations, 2nd edn. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Florida, pp 32–133

- 5.Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R (2005) Quality of life in older people: a structured review of generic self-assessed health instruments. Qual Life Res 14:1651–1668 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hoeksma HL, Van CHM, Ronday HK, Ronday HK, Heering A, Breedveld FC (2003) Comparison of the responsiveness of the Harris hip score with generic measures for hip function in osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis 62:935–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kiebzak GM, Campbell M, Mauerhan DR (2002) The SF-36 general health status survey documents the burden of osteoarthritis and the benefits of total joint arthroplasty: but why should we use it? Am J Manag Care 8:463–474 [PubMed]

- 8.Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS (2003) Patient relevant outcomes after total hip replacement: a comparison between different surgical techniques. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:21–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Ostendorf M, van Stel HF, Buskens E, Schrijvers AJ, Marting LN, Verbout AJ, Dhert WJ (2004) Patient-reported outcome in total hip replacement: a comparison of five instruments of health status. J Bone Joint Surg Br 86:801–808 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Pacault-Legendre V, Courpied JP (1999) Survey of patient satisfaction after total arthroplasty of the hip. Int Orthop 23:23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Patt JC, Mauerhan DR (2005) Outcomes research in total joint replacement: a critical review and commentary. Am J Orthop 34:167–172 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Quintana JM, Escobar A, Arostegui I, Bilbao A, Azkarate J, Goenaga JI, Arenaza JC (2006) Health-related quality of life and appropriateness of knee or hip joint replacement. Arch Intern Med 166:220–226 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Salaffi F, Carotti M, Grassi W (2005) Health-related quality of life in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: comparison of generic and disease-specific instruments. Clin Rheumatol 24:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Sporer SM, Obar R, Bernini PM (2004) Primary total hip arthroplasty using a modular proximally coated prosthesis in patients older than 70. J Arthroplasty 19:197–203 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Tseng HM, Lu JFR, Gandek B (2003) Cultural issues in using the SF-36 health survey in Asia: results from Taiwan. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Ware JE, Kosinski MK, Keller SD (1994) SF-36 Physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston

- 17.Ware JE (1993) SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston

- 18.Welsing PM, Landewe RB, Riel PL, Boers M, van Gestel AM, van der Linden S, Swinkels HL, van der Heijde DM (2004) The relationship between disease activity and radiologic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 50:2082–2093 [DOI] [PubMed]