Abstract

Recently, 24nm polymer nanoparticles were found to access a privileged non-degradative intracellular pathway that leads to perinuclear accumulation. Here, we report the intracellular dynamics of vesicles containing polymer nanoparticles within this non-degradative pathway, characterized by clathrin- and caveolae- independent endocytosis, as compared to endosomes originating from classical clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Similar to transport of acidic endosomes and lysosomes, the dynamic movements of non-degradative vesicles exhibit substantial heterogeneity, including caged diffusion and pearls-on-a-string trajectories, a reflection of microtubule-dependent active transport that leads to rapid accumulation near the cell nucleus. However, the ensemble-averaged intracellular transport rate of vesicles in the non-degradative pathway is 4-fold slower than that of the acidic vesicles of late endosomes and lysosomes, highlighted by a 3-fold smaller fraction of actively transported vesicles. The distinct intracellular dynamics further confirms that small nanoparticles are capable of entering cells via a distinct privileged pathway that does not lead to lysosomal processing. This non-degradative pathway may prove beneficial for the delivery of therapeutics and nucleic acids to the nucleus or nearby organelles.

Keywords: confocal particle tracking, endosomes, transport, microtubules

Introduction

Viruses utilize various internalization pathways and cellular organelles to infect cells [1–3]. However, synthetic drug and nucleic acid delivery systems typically use clathrin-mediated cell uptake pathways that lead to trafficking within the degradative endo/lysosomal pathway [4, 5]. Synthetic systems capable of exploiting diverse trafficking mechanisms for targeted delivery to specific intracellular compartments may enhance the efficacy of delivered therapeutics [6–9]. The efficacy of drug and gene carriers taken up by different mechanisms have been increasingly investigated [10–12]. We have recently shown that the physical dimensions of polymeric nanoparticles can dictate their cellular fate [13]. In particular, a reduction in size of nanoparticles (from 43nm to 24nm) resulted in preferential particle uptake via a clathrin- and caveolae- independent mechanism. These particles were shown to be internalized into membrane bound vesicles in an energy dependent fashion. This pathway leads to particle trafficking in non-degradative/non-acidic vesicles that rapidly localize to the periphery of the cell nucleus [13].

Here we report the intracellular dynamics of particle-loaded vesicles of this non-degradative pathway compared to those of acidic vesicles containing particles internalized via classical clathrin-mediated endocytosis in the same cells. The characterization is achieved with high temporal and spatial resolution in live cells by combining multiple particle tracking (MPT) with confocal microscopy, a technique termed confocal particle tracking (CPT) [14–16]. CPT allows simultaneous multi-color tracking of dozens of particles within live cells, in real time with high temporal and spatial resolution. We find that non-acidic vesicles containing 24nm particles experience longer average residence times near the cell nucleus compared to acidic vesicles containing 43nm particles as a result of distinct dynamic transport rates in live cells.

Materials & Methods

Cell Culture

HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in MEM (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). For live-cell microscopy studies, HeLa cells were seeded between 1–2.5 × 105 cells per plate onto 35-mm glass-bottom tissue culture plates (MatTek Corp., Ashland, MA).

Confocal Microscopy

A confocal microscope (LSM 510 Meta, Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) was used to capture the dynamic motions acidic and non-acidic vesicles, which were labeled with exogenously added 43 and 24nm COOH-modified fluorescent polystyrene beads (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; final conc 2.0×10−5 w/v) respectively for 2h prior to microscopy, as previously described [13]. Fluorescent nanoparticles (NP) were used without further modification and actual sizes were determined to be 24nm +/− 4nm and 43nm +/− 6nm with no overlap in sizes as determined by dynamic light scattering using a Zetasizer 3000 (Malvern Instruments, Southborough, MA). Samples were excited with 488nm or 543nm laser, and images were captured by multi-tracking to avoid bleed-through between the fluorophores. To achieve the necessary acquisition speed and signal to noise ratio in the movies, while obtaining the thinnest possible optical slice, the pinhole diameters were set to less than 1 airy unit. After adjustment of the pinholes of both lasers to obtain the same optical slices, the optimal optical section that fulfilled our criteria ranged from less than 0.8 to less than 0.7 μm. Movie acquisition rate was limited to 200 ms per frame. All samples were maintained at 37°C using an air stream stage incubator (Nevtek, Burnsville, VA) and observed under a 100X/1.4 NA oil-immersion lens.

Multiple Particle Tracking Transport Mode Classification

Endosome motion was obtained by tracking the x,y movements. Light-intensity-weighted centroid of diffraction-limited images was tracked using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Corp., Downingtown, PA), thereby achieving resolution much higher than a pixel [15]. The coordinates of endosome centroids were transformed into families of time-averaged mean squared displacements (MSD), <Δr2(τ)> = [x(t +τ) − x(t)]2 + [y(t+τ) − y(t)]2 (τ = time scale or time lag), from which distributions of time-dependent MSDs were calculated. The effective diffusivities (Deff) of individual endosomes are calculated from MSD = 4Deff τ. Bulk transport properties are obtained by geometric averaging of individual ensemble transport rates. The mechanism of endosome transport over short and long time scales was classified based on the concept of relative change (RC) of effective diffusivity (Deff), as discussed previously [16, 17]. In brief, RC values of endosomes at short and long probed time scales were calculated by dividing the Deff of a particle at a probed time scale by the Deff at an earlier reference time scale. By calculating RC values for two time regimes (i.e. short and long time scales), one can obtain the transport mode that describes the endosome motions over different length and temporal scales. For the analysis undertaken, RC for the short time scales was defined at a reference time scale τ = 0.2s and a probed τ = 1s, whereas the RC for long time scales was found at reference τ = 5s and probed τ = 10s. An RC standard curve, which plots the 95% distribution range of Deff for purely Brownian particles over time scale, was generated based on Monte Carlo simulations and confirmed by tracking polystyrene nanoparticles in glycerol (data not shown). Endosomes with a RC value between the upper and lower bounds is classified as diffusive, below the lower bound is hindered-diffusion, and above the upper bound is active. Immobile particles are defined as those that display an average MSD smaller than the 10nm resolution at a time scale of 1s.

Results & Discussion

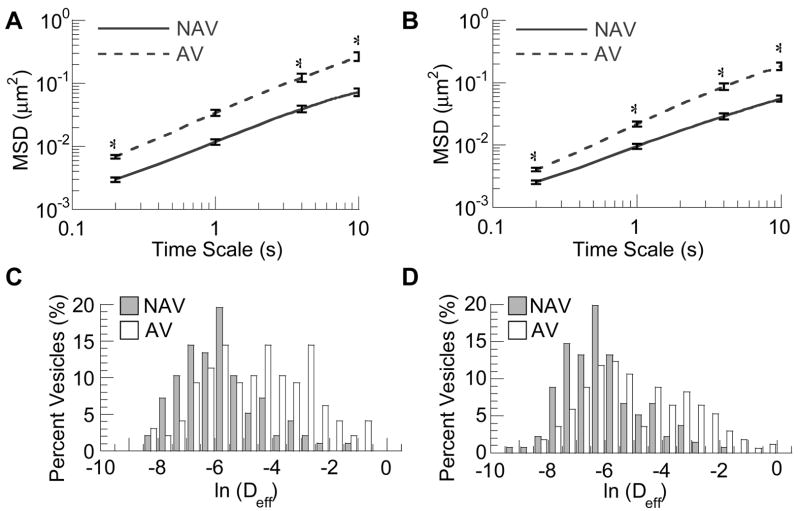

The dynamics of acidic vesicles (AV) and non-acidic vesicles (NAV) were recorded in the same HeLa cells in 40s movies with 200ms resolution (Supplementary Movie 1). The NAV pathway was labeled with red fluorescent polymeric nanoparticles (dn = 24 +/− 4nm) and acidic vesicles were labeled with yellow-green fluorescent polymeric nanoparticles (dn = 43 +/− 6nm). Distinct cellular localization for the 24 and 43nm particles was observed (Fig 1A-C), as expected based on our previous report [13]. Sample trajectories tracing the motions of NAV and AV (Figure 1D & 1E) revealed substantial heterogeneity in their intracellular dynamics. In particular, there were vesicles for both pathways whose motions were strongly hindered (steric obstruction or adhesion to the cellular environment), diffusive (random walk behavior), or indicative of active transport (large and directed displacements). Trajectories of vesicles undergoing active transport for both pathways resembled pearls-on-a-string motions with linear or curvilinear trajectories, in agreement with microtubule-dependent, motor protein driven transport, as previously reported for AV and synthetic polymer-based gene carriers [18]. Both NAV and AV populations were found primarily in the perinuclear space within 2hrs of incubation.

Figure 1.

Transport and locations of different intracellular vesicles. (A) Non-clathrin, non-caveolae vesicles (NAV) and (B) acidic vesicles (AV) are trafficked to different locations in a HeLa cell 4 h post-transfection. The nucleus is depicted by N. Overlay image is shown in (C). Sample trajectories (up to 40s) of different vesicles in the same cell are shown in (D) and (E) respectively. A small number of (D) NAV and a significant number of AV displayed active transport with linear or curvilinear trajectories.

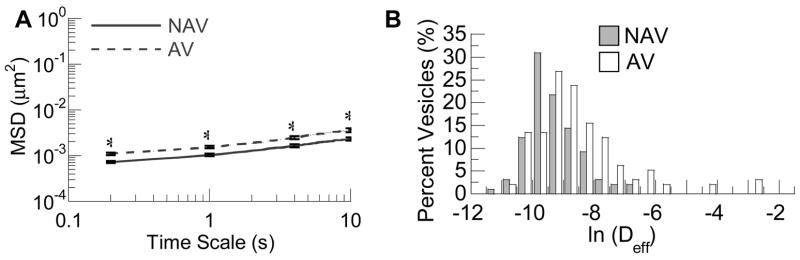

Quantitative measurements of the mean squared displacements (MSD) of dozens of individual particles in live HeLa cells showed distinct differences in the intracellular dynamics for each vesicle type (Fig 2A & B). The ensemble-averaged MSD (<MSD>) was roughly 4-fold higher for AV compared to NAV across all time scales at both 2h and 4h after incubation. To further evaluate the differences in transport, we plotted the distribution of natural logarithmic effective diffusivities (ln(Deff)) of vesicles at a time scale of 10s (Figure 2C & 2D). Reflective of the heterogeneity in their observed trajectories, measured diffusivity values of vesicles of both pathways spanned several orders of magnitude. There was substantial overlap in the ln(Deff) values of NAV and AV between −8 to −4. However, whereas the displacements of the slowest AV and NAV were similar, AV had a substantially greater number of fast moving vesicles (ln(Deff) between −4 to −1). At both time points, the fastest AVs were more than 10-fold faster than the fastest NAVs.

Figure 2.

Intracellular transport of non-clathrin, non-caveloae vesicles (NAV, solid lines) compared to acidic vesicles (AV, dashed lines). The ensemble geometric mean squared displacements (<MSD>) with respect to time scale at 2hrs post-incubation (A), 4hrs post-incubation (B). The difference in the MSD for NAV compared to AV was statistically significantly across all time scales (p<0.05). Standard errors at selected time scales are plotted. The corresponding distributions of natural logarithmic effective diffusivities (ln(Deff)) at a time scale of 10s for NAV and AV at 2hrs post-incubation (C), 4hrs post-incubation (D).

To characterize the mechanism of vesicle transport, we classified the motions of each AV and NAV into hindered, diffusive, and active transport based on the concept of relative change in effective diffusivity, as reported previously [16, 17] and in more detail in materials and methods. At both time points, only 13–15% of the NAVs underwent active transport, whereas between 40% to 45% of the AVs underwent active transport (Table 1, p<0.05). The substantial difference in the fraction of actively transported vesicles was in good agreement with the greater number of fast moving AV from analysis of ln(Deff) distribution. The heterogeneous transport observed from vesicle traces was supported by the substantial populations in each transport regime (Table 1). Overall, the fractions of vesicles exhibiting each transport mode between 2hrs and 4hrs after incubation were similar, suggesting that equilibrium of vesicular dynamics was reached by 2hrs.

Table 1.

Transport mode distributions of acidic vesicles (AV) and non-clathrin, non-caveolae vesicles (NAV) in live HeLa cells at 2hrs and 4hrs post-incubation, and 4hrs post-incubation with nocodazole (+Noc) treatment 1hr prior to microscopy. The transport modes are classified into hindered diffusion (H), diffusive (D), and active transport (A). n represents the number of vesicles tracked.

| Time | Pathway | n | Hindered | Diffusive | Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 hr | NAV | 97 | 45% | 39% | 15% * |

| 2 hr | AV | 125 | 35% | 20% | 45% |

| 4 hr | NAV | 136 | 50% | 37% | 13% * |

| 4 hr | AV | 170 | 28% | 33% | 39% |

| 4 hr | NAV +Noc | 107 | 100% | 0% | 0% # |

| 4 hr | AV +Noc | 115 | 98% | 0% | 2% |

denotes statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between the active transported fraction between NAV and AV at both 2hr and 4hr time points.

denotes significant difference between nocodazole treated and untreated active fractions.

A direct consequence of the slower transport of NAVs is an extended residence time in the perinuclear space of cells, due to their perinuclear trafficking [13]. Prolonged retention time in close proximity to the nucleus may have important implications in the delivery of therapeutics targeted to the nucleus utilizing this unique trafficking pathway, including chemotherapeutic agents, transcription inhibitors, and nucleic acids for gene therapy. In particular, the molecularly crowded cytoplasm can inhibit efficient diffusion of many macromolecules and prevent therapeutics, released far from the intended site of action in the cytoplasm, from reaching their target [8, 14, 19, 20]. By increasing the ensemble-averaged residence time in the perinuclear space, the concentration of therapeutics delivered near the nucleus may be enhanced, thereby improving therapeutic efficacy. Thus, in addition to their non-degradative biochemical characteristics, the unique spatiotemporal dynamics of NAV vesicles may prove beneficial for the delivery of therapeutics to the nucleus or nearby organelles.

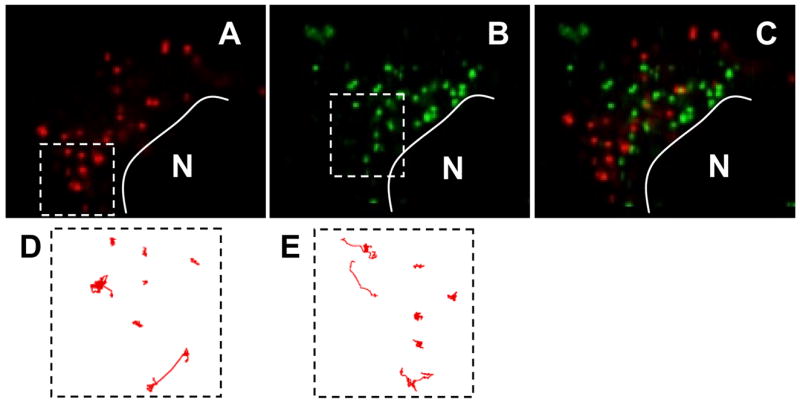

Intracellular active transport is typically mediated by motor proteins utilizing microtubules; we thus tested the effect of microtubule depolymerization on the transport of both AV and NAV. In agreement with previous reports [18], depolymerization of microtubules abolished virtually all actively moving fractions of AV (Fig 3), leading to an ~60-fold decrease in <MSD> values (τ = 10s). Likewise, microtubule depolymerization eliminated all active trajectories of NAV, leading to an ~25-fold decrease in <MSD> (τ = 10s). It is not surprising that the mechanism of vesicular (~100–400nm in size) transport became almost exclusively hindered in microtubule depolymerized cells, as the intracellular actin network, with a pore size of ~50nm [21, 22], remained intact. The observed difference in the <MSD> change (~25-fold for NAV vs. ~60-fold for AV) may be partially explained by the lower percentage of actively transported particles and the smaller displacements of the active fractions in the NAV pathway in cells with intact microtubules. MSD versus τ scales as τ2 for actively transported species [18], which was also confirmed here (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Intracellular transport of non-clathrin, non-caveloae vesicles (NAV, solid lines) compared to acidic vesicles (AV, dashed lines) at 4hrs post-incubation in cells treated with 10μM nocodazole for 1 hr prior to microscopy. The ensemble geometric mean squared displacements (<MSD>) with respect to time scale (A) and the corresponding distributions of natural logarithmic effective diffusivities (ln(Deff)) at a time scale of 10s for NAV and AV. The difference in the MSD for NAV compared to AV was statistically significantly across all time scales (p<0.05). Standard errors at selected time scales are plotted.

The mechanisms contributing to the differences in the fraction of vesicles undergoing active transport between the NAV and AV pathway remain unknown. A plausible explanation is that differences exist between NAV and AV with regard to the surface density and types of membrane associated proteins (MAPs) that bind to microtubule-associated motor proteins, dynein and kinesin, thus leading to reduced efficiency in directed long range displacements along microtubules for the NAV pathway. Alternatively, a higher association affinity of NAV vesicles to other cytoskeletal networks, such as actins and intermediate filaments, may also lead to lower probability of directed active transport via microtubules. Nevertheless, differences in the transport rates and the fractions of vesicles utilizing microtubule-dependent transport further confirms the earlier finding that 24nm particles are capable of distinct cellular trafficking outside of the typical endo/lysosomal pathway.

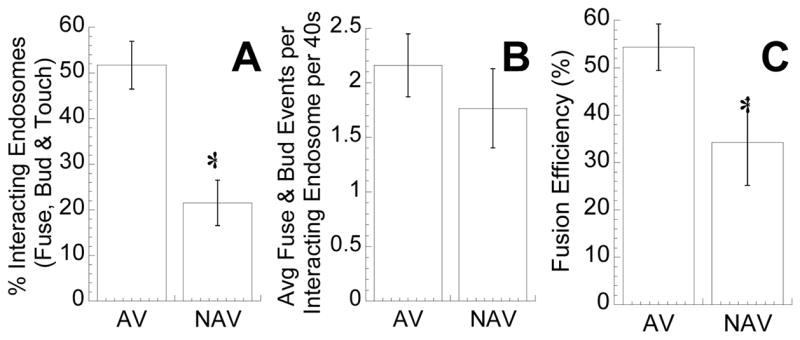

Vesicles are known to rapidly fuse and bud to achieve proper sorting of various cellular cargoes and for signal transduction [22–24]. We observed a significant number of kiss-and-run, budding and fusion events in each pathway. Budding and fusion are defined here as the clear separation and merging of fluorescence, respectively. Interestingly, the dynamics of these events in the NAV pathway were different from the AV pathway. A statistically greater fraction of AV interact with other AV (~50%), while the majority of NAV (~80%) remain isolated and free of intra-vesicular interactions over a 40s observation period (Figure 4A, p<0.05). Reduced percentages of touch, fuse and bud events for NAV may be directly related to their slower average transport, where the lower mobility limits the spatial dimensions they explore, leading to a decreased likelihood of encountering another vesicle. However, differences in the average number of fusion and budding events per interacting vesicle was not statistically significant for AV and NAV (Figure 4B). The number of fusion events approximately equaled the number of budding events for both pathways (data not shown). A small subset of vesicles appear to repeatedly undergo fusion and budding (Supplemental Movie 2), suggesting that inherent diversity of vesicles may exist even within the same trafficking pathway. The efficiency in vesicle fusion was significantly less for the NAV pathway (Figure 4C). All fusion and budding events ceased upon microtubule depolymerization, confirming the dependence of vesicular interactions on microtubules (Supplementary Movie 3).

Figure 4.

Vesicular fusion and budding over 40s. (A) Non-clathrin, non-caveloae vesicles (NAV) exhibited a lower average percentage of endosomes per cell that touch, bud or fuse with each other than acidic vesicles (AV) (n = 15 cells, n = 316 vesicles for NAV, n = 495 vesicles for AV; p < 0.05). (B) The average number of fusion and budding events per endosomes that either touch, bud or fuse with each other were not statistically different. (C) The fusion efficiencies, defined as the number of successful fusion events divided by the sum of fusion and touching events, were higher for AV when compared to NAV (p < 0.05).

An observation of note is the higher fraction of active transport in the AV pathway (39%) than what we previously reported for polyethylenimine/DNA nanocomplexes (17%) [18], which also traffic in acidic vesicles of the endo/lysosomal pathway. The disparity may be explained by differences in the length of the movies taken, since the length of the movie in the current study (40s) is twice as long as our previous work (20s). The probability that a vesicle will interact with motor proteins and become actively transported along the microtubule network increases with the length of the movie taken. Biochemical differences may also exist between AV labeled with negatively charged 43nm particles (current study) compared with positively charged ~150nm polyethylenimine/DNA nanocomplexes (previous study) that may partially account for the distinct transport kinetics observed here. Different methods of transport mechanism classification were used in the two studies; however, the method used here, based on the concept of relative change, predicted similar fractions of actively transported polyethylenimine/DNA nanocomplexes when applied to the Suh et al. [18] data. (data not shown).

In summary, we used high resolution confocal particle tracking to characterize the intracellular dynamics of NAVs as compared to AVs. Following perinuclear accumulation of each species at 2h post-transfection, NAV underwent directed long range displacements along microtubules at much lower frequency than endo/lysosomal vesicles originating from clathrin-mediated endocytosis. NAV also display distinct fusion and budding patterns, perhaps partly as a consequence of the distinct transport kinetics. The slower transport and non-acidic nature of NAV following non-clathrin- and non-caveolae- mediated endocytosis leads to a prolonged retention time of NAV near the nucleus, which may allow improved intracellular delivery of therapeutics to the nucleus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Integrated Imaging Center at Johns Hopkins University. We acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation (NSF 0346716), from the Natural Science & Engineering Research Council of Canada (PGSD for S.K.L.), and Office of the Provost of the Johns Hopkins University (PURA for C.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Conner SD, Schmid SL. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 2003;422(6927):37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR. Dissecting virus entry via endocytosis. J Gen Virol. 2002;83(Pt 7):1535–1545. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AE, Helenius A. How viruses enter animal cells. Science. 2004;304(5668):237–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1094823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen KD, Nori A, Tijerina M, Kopeckova P, Kopecek J. Cytoplasmic delivery and nuclear targeting of synthetic macromolecules. J Control Release. 2003;87(1–3):89–105. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng W, Parker TL, Kallinteri P, Walker DA, Higgins S, Hutcheon GA, Garnett MC. Uptake and metabolism of novel biodegradable poly (glycerol-adipate) nanoparticles in DAOY monolayer. J Control Release. 2006;116(3):314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan R. The dawning era of polymer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(5):347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrd1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gumbleton M, Hollins AJ, Omidi Y, Campbell L, Taylor G. Targeting caveolae for vesicular drug transport. J Control Release. 2003;87(1–3):139–151. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo D, Saltzman WM. Synthetic DNA delivery systems. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(1):33–37. doi: 10.1038/71889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medina-Kauwe LK, Xie J, Hamm-Alvarez S. Intracellular trafficking of nonviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2005;12(24):1734–1751. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huth US, Schubert R, Peschka-Suss R. Investigating the uptake and intracellular fate of pH-sensitive liposomes by flow cytometry and spectral bio-imaging. J Control Release. 2006;110(3):490–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rejman J, Bragonzi A, Conese M. Role of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis in gene transfer mediated by lipo- and polyplexes. Mol Ther. 2005;12(3):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanatani I, Ikai T, Okazaki A, Jo J, Yamamoto M, Imamura M, Kanematsu A, Yamamoto S, Ito N, Ogawa O, Tabata Y. Efficient gene transfer by pullulan-spermine occurs through both clathrin- and raft/caveolae-dependent mechanisms. J Control Release. 2006;116(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai SK, Hida K, Man ST, Chen C, Machamer C, Schroer TA, Hanes J. Privileged delivery of polymer nanoparticles to the perinuclear region of live cells via a non-clathrin, non-degradative pathway. Biomaterials. 2007;28(18):2876–2884. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suh J, Choy KL, Lai SK, Suk JS, Tang B, Prabhu S, Hanes J. PEGylation of Nanoparticles Improves Their Cytoplasmic Transport. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2007;2(4):1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suh J, Dawson M, Hanes J. Real-time multiple-particle tracking: applications to drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57(1):63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suk JS, Suh J, Lai SK, Hanes J. Quantifying the intracellular transport of viral and nonviral gene vectors in primary neurons. Exp Biol Med. 2007;232(3):461–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai SK, O’Hanlon DE, Harrold S, Man ST, Wang YY, Cone R, Hanes J. Rapid transport of large polymeric nanoparticles in fresh undiluted human mucus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(5):1482–1487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608611104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suh J, Wirtz D, Hanes J. Efficient active transport of gene nanocarriers to the cell nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):3878–3882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0636277100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luby-Phelps K. Cytoarchitecture and physical properties of cytoplasm: volume, viscosity, diffusion, intracellular surface area. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;192:189–221. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukacs GL, Haggie P, Seksek O, Lechardeur D, Freedman N, Verkman AS. Size-dependent DNA mobility in cytoplasm and nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(3):1625–1629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kole TP, Tseng Y, Jiang I, Katz JL, Wirtz D. Intracellular mechanics of migrating fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(1):328–338. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luby-Phelps K. Effect of cytoarchitecture on the transport and localization of protein synthetic machinery. J Cell Biochem. 1993;52(2):140–147. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240520205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothman JE, Wieland FT. Protein sorting by transport vesicles. Science. 1996;272(5259):227–234. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schekman R, Orci L. Coat proteins and vesicle budding. Science. 1996;271(5255):1526–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.