Abstract

To establish the optimum barium-based reduced-laxative tagging regimen prior to CT colonography (CTC). Ninety-five subjects underwent reduced-laxative (13 g senna/18 g magnesium citrate) CTC prior to same-day colonoscopy and were randomised to one of four tagging regimens using 20 ml 40%w/v barium sulphate: regimen A: four doses, B: three doses, C: three doses plus 220 ml 2.1% barium sulphate, or D: three doses plus 15 ml diatriazoate megluamine. Patient experience was assessed immediately after CTC and 1 week later. Two radiologists graded residual stool (1: none/scattered to 4: >50% circumference) and tagging efficacy for stool (1: untagged to 5: 100% tagged) and fluid (1: untagged, 2: layered, 3: tagged), noting the HU of tagged fluid. Preparation was good (76–94% segments graded 1), although best for regimen D (P = 0.02). Across all regimens, stool tagging quality was high (mean 3.7–4.5) and not significantly different among regimens. The HU of layered tagged fluid was higher for regimens C/D than A/B (P = 0.002). Detection of cancer (n = 2), polyps ≥6 mm (n = 21), and ≤5 mm (n = 72) was 100, 81 and 32% respectively, with only four false positives ≥6 mm. Reduced preparation was tolerated better than full endoscopic preparation by 61%. Reduced-laxative CTC with three doses of 20 ml 40% barium sulphate is as effective as more complex regimens, retaining adequate diagnostic accuracy.

Keywords: Colonography, Computed tomography, Barium sulfate, Cathartics

Introduction

Full bowel purgation remains a major cause of discomfort prior to any colonic investigation [1–3]. Furthermore, fluid and electrolyte imbalance may occur following aggressive cleansing [4]. A potential advantage of computed tomography colonography (CTC) over colonoscopy is the ability to reduce laxative requirements while maintaining diagnostic accuracy [5–7]. Reduced laxative regimens often incorporate orally ingested contrast agents to “tag” or “label” residual fluid and faecal residue. The ideal tagging regimen remains controversial but must be safe, effective, simple and well tolerated.

In many respects, barium is an ideal tagging agent: it has an established safety profile, is relatively palatable, produces minimal side effects, and is effective for tagging solid residue [8]. Previous work has shown adequate tagging may be achieved using low volumes of 40% w/v barium, although the ideal volume and dosing regimen has not been fully established [9]. Furthermore efficacy for fluid tagging has been questioned [9], with some investigators preferring iodine-based contrast either alone or in combination, claiming a more homogeneous fluid opacification better suited to digital subtraction [10]. We aimed to establish the optimum barium-based reduced-laxative faecal- and fluid-tagging regimen, to assess patient acceptability, and to document diagnostic accuracy compared to an enhanced colonoscopic reference standard.

Materials and methods

Full ethical committee approval was obtained, and all subjects gave written informed consent.

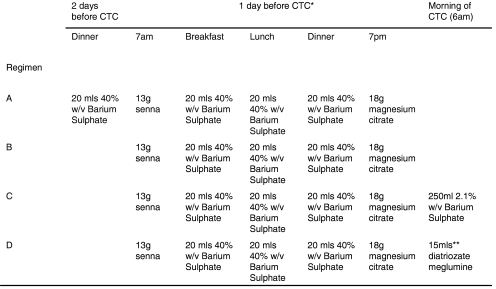

Consecutive patients were recruited from those scheduled to undergo afternoon diagnostic colonoscopy for symptoms suggestive of colorectal neoplasia (change in bowel habit, rectal bleeding, unexplained weight loss or palpable abdominal mass) from one of three institutions. Patients were excluded if below age 50 or if they had a known diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Eligible patients were invited to undergo CTC at 8 am, prior to same day colonoscopy and were randomised via a computer random number generator to one of four reduced-laxative regimens using barium-based faecal tagging [20 ml 40% w/v barium sulphate suspension (Tagitol V, EZEM, Lake Success, NY)] (Fig. 1). For each of the regimens, patients followed a low-residue diet 2 days before the CTC (avoiding fatty food, milk and vegetables). The day prior to CTC, all patients were allowed a low-residue meal kit (Nutraprep, EZEM), and ingested the same reduced-laxative protocol [13 g sachet of senna granules (Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare, Hull, UK) at 7 am and 18 g magnesium citrate (Lo-So prep, EZEM) at 7 pm]. This laxative regimen was defined as “reduced” given the normal laxative preparation prior to colonoscopy at the recruiting institutions includes an additional 18 g of magnesium citrate (see below). Overall fluid intake was restricted to 2.1 l the day prior to CTC for all four regimens.

Fig. 1.

Details of reduced-laxative tagging regimens. Taken with meals from low residue meal kit (single star). Diluted in 250 mls of water (double stars)

In an attempt to improve fluid tagging, two regimens (C and D) included either an additional 250 ml 2.1% w/v barium sulphate (Readi-Cat Banana Smoothie, EZEM) or 15 ml meglumine amidotrizoate (10 g sodium amidotrizoate/66 g meglumine amidotrizoate per 100 ml; Gastrograffin, Schering) diluted in 250 ml of water, taken 2 h prior to CTC [11]. Patients otherwise took nothing by mouth the day of the CTC.

Study power

The study was powered to detect a 20% difference in tagging quality (see below) across the four regimens. Based on pilot data, the interclass correlation coefficient between colonic segments was calculated to be 0.30, and it was calculated that a sample size of 22 per group was required (alpha 0.05 at 80% power).

CT colonography

Prone and supine CTC was performed with automated CO2 insufflation (Protocol pump, EZEM) [12], using either a 4-detector-row (GE Lightspeed Plus, GE, Milwaukee, WI, USA; 120 kV, 50 mA, 2.5 mm collimation, slice reconstruction 1.25 mm, pitch 1.5, n = 82 patients) or 64-detector-row scanner (Siemens Somatom Sensation 64, SEMS, Germany; 120 kV, 50 mA, 0.6 mm collimation, pitch 0.24, n = 13 patients).

One of three experienced radiologists (each with experience of at least 300 CTC cases with endoscopic validation) evaluated the datasets immediately after the examination using a dedicated workstation with proprietary software (Vitrea 3.8, Vital Images, Minnetonka, MN, USA), and noted the segmental location of any polyps or cancers on a study report sheet, together with lesion size measured using electronic callipers applied to the 2D MPR best showing the maximum diameter. The choice of reporting radiologist for each patient was dependent upon the particular recruiting institution and availability on the day of the scan. All three radiologists used a primary 2D approach with 3D reserved for problem solving.

Colonoscopy

Immediately following CTC patients ingested a further 18 g of magnesium citrate in order to complete the normal endoscopic cleansing regimen prior to afternoon colonoscopy. Colonoscopy was performed as per usual practice by one of five experienced endoscopists, on average 6 h (range 4–8 h) after the CTC scan. Segmental unblinding was used as described previously [13, 14], using the sealed CTC report. In brief, the CTC report was handed to the endoscopy nurse accompanying the patient. CTC findings were revealed to the colonoscopist by the nurse on a segmental basis (caecum to rectum) once examination of each colonic segment was deemed complete during extubation of the colon. If CTC suggested a lesion had been missed, the segment was re-intubated and a second segmental examination performed. There was no time limit imposed on the colonoscopist for this second look. All polyps were photographed, their sizes estimated by direct comparison to adjacent open biopsy forceps, and then excised for histology where possible.

Polyp correlation

Polyps found at CTC were deemed true positive if a corresponding polyp was found in the same or adjacent segment at endoscopy and if the estimated size of the polyp was within 50% of the endoscopic measurement.

Patient experience

Immediately following CTC a questionnaire was administered [15] investigating patient experience of the reduced-laxative tagging regimen (Table 1). Patient responses were compared to a historical cohort of 69 symptomatic patients recruited from the same endoscopy lists during a prior study comparing CTC to colonoscopy [16]. As part of this prior study, patients had undergone full bowel preparation [13 g senna granules and two doses of 18 g magnesium citrate (total 36 g) prior to CTC] and had completed the same questionnaire under similar circumstances.

Table 1.

Bowel-tolerance questionnaire questions and responses in comparison to historical controls undergoing full bowel preparation

| Variable | Response | Reduced preparationa, n (%) | Historical controls [full preparation]b, n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How did you find understanding prep sheet? | Easy | 56 (63) | 48 (70) | 0.39 |

| Fairly easy/difficult | 33 (37) | 21 (30) | ||

| How did you find swallowing medicine? | Easy | 43 (48) | 44 (64) | 0.36 |

| Fairly easy | 36 (40) | 32 (32) | ||

| Quite difficult/difficult | 10 (11) | 3 (4) | ||

| How did you find coping with special diet? | No problem | 59 (66) | 42 (61) | 0.49 |

| Bit difficult | 24 (27) | 24 (35) | ||

| Very difficult | 6 (7) | 3 (4) | ||

| How did you feel after medicine? | Fine | 65 (73) | 48 (70) | 0.96 |

| Unwell/very unwell | 24 (27) | 21 (30) | ||

| Did you have any abdominal pain? | None | 31 (36) | 25 (36) | 0.37 |

| Mild | 39 (45) | 27 (39) | ||

| Moderate/severe | 16 (19) | 17 (25) | ||

| Did you have any nausea/vomiting? | None | 58 (67) | 46 (67) | 0.92 |

| Mild | 22 (26) | 18 (26) | ||

| Moderate/severe | 6 (7) | 5 (7) | ||

| Did you experience any faintness or dizziness? | None | 70 (81) | 54 (78) | 0.63 |

| Mild/moderate/severe | 16 (29) | 15 (22) | ||

| Did you experience any wind? | None | 25 (29) | 26 (38) | 0.27 |

| Mild | 41 (48) | 32 (46) | ||

| Moderate/severe | 20 (23) | 11 (16) | ||

| Did you experience any soreness? | None | 37 (43) | 24 (35) | 0.15 |

| Mild | 37 (43) | 29 (42) | ||

| Moderate/severe | 12 (14) | 16 (23) | ||

| Did you experience any incontinence? | None | 68 (80) | 49 (71) | 0.2 |

| Mild | 8 (9) | 13 (19) | ||

| Moderate/severe | 9 (11) | 7 (10) | ||

| Did you experience any sleep disturbance? | None | 33 (39) | 41 (59) | 0.01 |

| Mild | 29 (34) | 20 (29) | ||

| Moderate/severe | 23 (27) | 8 (12) | ||

| How many times did you open your bowel after starting the preparation? | 1–3 | 1 (1) | N/A | |

| 3–5 | 20 (22) | |||

| >5 | 69 (77) |

N/A Not applicable (not asked)

a13 g senna plus 18 g magnesium citrate

b13 g senna plus 36 g magnesium citrate

One week later a follow-up questionnaire (Table 2) was mailed to the current study cohort investigating tolerance of the preparation prior to CT and preference, if any, over the full preparation required for subsequent colonoscopy.

Table 2.

Questions and responses to follow-up questionnaire pertaining to patient tolerance and preferences

| Variable | Response | Patient number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| How did you find taking the low-residue diet? | No problem | 46 (67%) |

| Moderately inconvenient | 20 (29%) | |

| Very inconvenient | 3 (4%) | |

| How did you find drinking the tagging liquid? | No problem | 57 (83%) |

| Moderately inconvenient | 11 (16%) | |

| Very inconvenient | 1 (1%) | |

| How did you tolerate the preparation before CT? | Well | 37 (53%) |

| Fairly well | 29 (42%) | |

| Poorly | 3 (4%) | |

| How did you tolerate the additional preparation prior to colonoscopy, compared to that before the CT? | No problem | 51 (74%) |

| More uncomfortable | 12 (17%) | |

| Much worse | 6 (9%) | |

| How did you find the preparation before CTC compared to the full colonoscopy preparation? | Much better | 18 (26%) |

| Better | 24 (35%) | |

| No better | 26 (38%) |

Grading of bowel preparation

Two experienced radiologists (both with experience of over 700 validated CTC cases) in consensus retrospectively reviewed all CTC examinations, grading the quality of preparation and success of tagging. Observers were unaware of the tagging regimen used and divided the colon into six segments (rectum to caecum) for analysis [17].

Grading of residual stool (irrespective of tagging status) was based on the percentage of total mucosal circumference coated on an axial image. For each colonic segment, the slice with the most residual stool was used to assign the score. Scores were as follows: 1: no residue or scattered residue, 2: coating of <25% or thin circumferential “film” less than 2 mm in depth, 3: coating of ≥25 to 50%, 4: >50% coating.

Grading of residual fluid (irrespective of tagging status) was based on the maximum anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the colonic lumen submerged. For each colonic segment, the slice with the most residual fluid was used to assign the score. Scores were as follows: 1: no fluid, 2: <25% AP diameter, 3: ≥25 to 50% AP diameter, 4: >50% AP diameter.

The quality of tagging for solid residue and fluid was scored using a system adapted from Lefere at al. [9] and assigned for supine and prone positions combined for each colonic segment. Residual stool was divided into that measuring ≤5 mm and ≥6 mm (based on 2D measurement using electronic calipers), and the number of stool balls ≥6 mm was counted for each patient. Readers assessed the percentage of total residual stool volume (for each size category) that had been tagged for each colonic segment. Scores were assigned as follows: 1: all residual stool untagged, 2: 1 to <25% tagged, 3: 25 to <50% tagged, 4: 50 to <75% tagged, 5: 75 to 100% tagged.

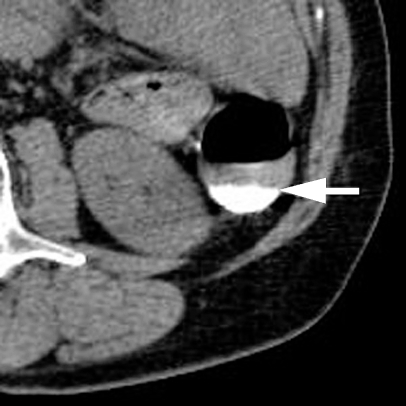

Tagging of residual fluid was scored as follows: 1: fluid untagged, 2: layered tagging (a mix of tagging densities in one fluid level with a denser dependent layer and visibly less dense non-dependent layer (Fig. 2), 3: fluid homogeneously tagged (single tagging density). The density of tagged fluid (in HU) was also recorded by taking the average of three regions of interest drawn in the deepest fluid pool for each colonic segment. If fluid was layered (Fig. 2), the minimum and maximum HU was recorded. Finally observers recorded their confidence using a percentage score that, based on the bowel preparation, they would be able to exclude a polyp ≥6 mm in day-to-day clinical practice for each colonic segment.

Fig. 2.

A 68-year-old female with change in bowel habit. Axial CT colonographic image demonstrating layering of contrast (arrow) within tagged fluid

Statistical analysis

Preliminary data analysis revealed skewed data for most bowel preparation and tagging variables, and thus scores were combined for subsequent analysis. For residue, scores were grouped into either a score of 1, or a score of 2 or more. For residual fluid, scores were grouped into scores of 1/2, or scores of 3/4. Scores for solid residue tagging were grouped into those of ≤4 or 5. Fluid tagging scores were grouped into scores of 1/2, or score of 3. Logistic regression was then applied, adjusting for colonic segment, to compare the four regimens overall, and to compare the distal (rectum, sigmoid, descending) and proximal colon (transverse, ascending and caecum). In addition, the prevalence of layering within tagged fluid was compared on a per-patient basis using the chi-squared test. Tagged fluid attenuation was compared using linear regression following log transformation of the data. Confidence scores for excluding a polyp ≥6 mm were grouped as either <100% or 100%, and compared using logistic regression. For all regression analyses, robust standard errors were employed to account for interdependency between colonic segments and scan position (supine/prone) in the same patient. Results were expressed as the odds of the outcome under consideration compared to regimen A.

Questionnaire responses were compared using Fischer’s exact test.

Overall categorical per-polyp and per-patient data are presented using descriptive statistics. Given the relatively low polyp incidence (and thus low statistical power), comparative statistics for polyp detection were not performed across regimens. False-positive numbers were compared using one-way ANOVA.

Results

A total of 95 patients were recruited (50 female, mean age 64 years, range 50–85 years), with 24, 25, 24 and 22 randomised to regimens A to D respectively. Seventy-seven, 13 and 5 patients were recruited from institutions 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Overall, 67 (71%) had a change in bowel habit, 18 (19%) had rectal bleeding, 7 (7%) had non-specific weight loss, and 3 (3%) had a clinically palpable abdominal mass.

Bowel preparation

The percentage of segments (supine and prone combined) assigned a score of 1 for residual solid residue (i.e. no residue or scattered) was 76% (218/288), 82% (246/300), 81% (232/288) and 94% (247/264), for regimens A to D respectively, and on average there were 2.5, 2.0, 2.8 and 1.1 stool balls ≥6 mm per patient. The improved quality of preparation in regimen D reached statistical significance [odds of score 2–4: 0.19 (95% CI: 0.07, 0.56), P = 0.02]. Across all regimens, the distal colon was significantly better prepared then the proximal colon (P = 0.006). For example the number of segments assigned at least a score of 2 for solid residue in the caecum was 42% (20/48), 48% (24/50), 35% (17/48) and 23% (10/44) for regimens A to D respectively, compared to 25% (12/48), 16% (8/50), 21% (10/48) and 0% (0/44) for the rectum.

The percentage of segments (supine and prone in total) assigned a score of 1 or 2 for residual fluid was 51% (148/288), 59% (178/300), 53% (153/288) and 43% (114/264) for regimens A to D respectively. There was no significance difference between groups either overall or between the proximal and distal colon (P = 0.22–0.37).

Tagging quality

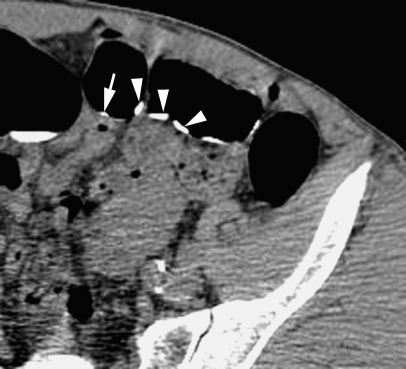

Tagging quality was generally good (mean tagging score 3.7–4.5) (Fig. 3). While there was weak evidence of improved proximal colonic tagging for residue ≤5 mm for regimens C and D (P = 0.08), overall there was no difference in the efficacy of solid residue tagging across regimens (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

A 54-year-old male with unexplained rectal bleeding. Axial CT colonographic image showing homogeneous tagging of stool ≤5 mm (arrow) and ≥6 mm (arrowhead) in size

Table 3.

Efficacy of tagging of solid residue according to size and regimen

| Solid residue size | Colon segments | Regimen | Mean tagging score (SD) | Odds ratio (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 mm | All segments | A | 4.3 (1.2) | 1 | |

| B | 4.3 (1.2) | 0.94 (0.39, 2.32) | |||

| C | 4.5 (1.1) | 1.47 (0.56, 3.87) | |||

| D | 4.5 (1.2) | 1.67 (0.68, 4.14) | 0.56 | ||

| Distal colonb | A | 1 | |||

| B | 0.97 (0.37, 2.52) | ||||

| C | 0.76 (0.26, 2.27) | ||||

| D | 1.00 (0.38, 2.61) | 0.97 | |||

| Proximal colonc | A | 1 | |||

| B | 0.85 (0.26, 2.80) | ||||

| C | 4.06 (0.74, 22.1) | ||||

| D | 3.22 (0.95, 10.9) | 0.08 | |||

| ≥6 mm | All segments | A | 4.1 (1.6) | 1 | |

| B | 4.3 (1.5) | 1.82 (0.44, 7.62) | |||

| C | 4.1 (1.7) | 1.56 (0.32, 7.76) | |||

| D | 3.7 (1.8) | 0.43 (0.11, 1.65) | 0.24 | ||

| Distal colonb | A | 1 | |||

| B | 1.30 (0.26, 2.52) | ||||

| C | 3.84 (0.37, 39.2) | ||||

| D | 0.17 (0.02, 1.27) | 0.12 | |||

| Proximal colonc | A | 1 | |||

| B | 3.22 (0.26, 39.8) | ||||

| C | 0.94 (0.11, 7.87) | ||||

| D | 0.91 (0.11, 7.54) | 0.78 |

SD Standard deviation

aOdds of tagging score of 5 (best) compared to regimen A

bRectum, sigmoid and descending colon combined

cTransverse, ascending colon and caecum combined

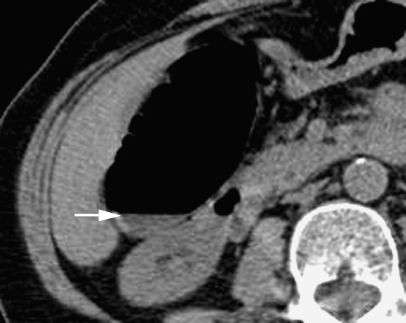

The average per-segment fluid tagging score was 2.5 (SD 0.8), 2.3 (SD 1.0), 2.5 (SD 0.9) and 2.4 (SD 1.2) for regimens A to D respectively. The odds of homogeneous tagging (i.e score 3) did not differ across the four regimens either overall or between the proximal and distal colon (P = 0.65–0.95). In total, 4% (6/144), 1% (2/150), 2% (3/144) and 5% (6/132) of segments respectively contained non-tagged fluid (score 1) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A 75-year-old female with change in bowel habit. Axial CT colonographic image showing failure of fluid tagging (arrow) (grade 1)

Overall 33% (8/24), 44% (11/25), 38% (9/24) and 36% (8/22) of patients receiving regimens A to D respectively had at least one segment with layering of tagged fluid (P = 0.89) (Fig. 2).

Fluid tagging density

In terms of mean HU of the tagged fluid (excluding the least tagged layer if tagging was layered), there was no significant difference among the four regimens, either overall or between the proximal/distal colon (P = 0.14–0.86). The mean HU of tagged fluid was 522 (SD 283), 504 (SD 395), 430 (SD 268), and 491 (SD 269) for regimens A to D respectively.

However in those segments with layering of contrast, the maximum attenuation (HU) of the least tagged layer was significantly higher for regimens C and D than for regimens A and B (P = 0.002) [77 (SD 105), 119 (SD 139), 155 (SD 118) and 174 (SD 122), for regimens A to D respectively].

Patient experience

A total of 89 of 95 (94%) patients completed the questionnaire (Table 1), although responses were incomplete in 4. Demographic data for the present study cohort (50 female, mean age 64 years, range 50–85 years) were not significantly different from the 69 historical controls (36 female, mean 63 years, range 35–85 years) [16]. Other than sleep disturbance (worse after reduced preparation) (P = 0.01), there was no significant difference in reported tolerance of the reduced and full bowel preparation regimens for any of the factors tested.

Follow-up questionnaire

Sixty-nine (73%) patients returned the follow-up questionnaire (Table 2). Overall 95% tolerated the reduced preparation regimen well or fairly well, and most (83%) found drinking the tagging agents acceptable. Although most [51/69 (74%)] found the additional preparation required for colonoscopy “no problem”, a majority (61%) found the reduced preparation regimen “better” or “much better” than the full preparation required for colonoscopy.

Diagnostic performance

Five patients (one each from regimens A, B, and C and two from regimen D) were excluded from the performance analysis due to a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (all presenting with rectal bleeding). A further patient (from regimen B) was excluded after refusing colonoscopy. Of the remaining 89 patients, 68 had either normal colonoscopy or diminutive polyps (≤5 mm) only, and 21 had at least one polyp ≥6 mm or cancer. Colonoscopy was incomplete in 10/89 (11%) reaching the transverse colon in 6, sigmoid in 3 and hepatic flexure in 1. Reasons for failure were obstructing stricture (1), severe diverticulosis (1), tortuous colon (5), and pain (3). Only those segments visualised at colonoscopy were included in the assessment of diagnostic performance.

Per polyp analysis

In total there were 9 polyps ≥10 mm (all adenomatous), 12 polyps 6–9 mm (10 adenomatous, 2 hyperplastic) and 72 polyps ≤5 mm (46 were recovered for histology, of which 26 were adenomatous, 15 hyperplastic and 5 normal mucosa). One 6-mm polyp and two 5-mm polyps were found only on re-look endoscopy after segmental unblinding of the CTC report. No CTC-detected polyps were classified as false positives due to segmental or size mismatching with colonoscopy.

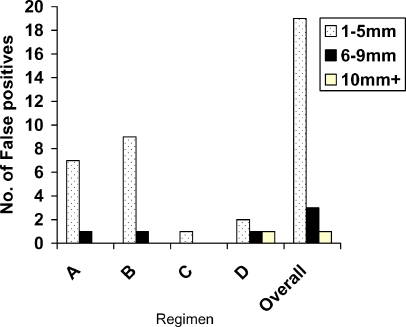

Summed across regimens A–D, detection of cancer, polyps ≥10 mm, 6–9 mm and ≤5 mm was 2/2 (100%), 8/9 (89%), 9/12 (75%) and 23/72 (32%) respectively (Fig. 5) (Table 4). In total there were only four false positives ≥6 mm (Figs. 6 and 7), with no significant difference between regimens (P = 0.15).

Fig. 5.

A 71-year-old male with rectal bleeding. Axial CT colonographic image demonstrating a 30-mm rectal cancer (arrow). Note the adjacent well-tagged residue (arrowheads)

Table 4.

Polyp detection overall and according to tagging regimen

| Regimen | Patient number | Detection cancer, n (%) | Detection 10 mm+, n (%) | Detection 6–9 mm, n (%) | Detection 1–5 mm, n (%) | False positive 10 mm+, n | False positive 6–9 mm, n | False positive 1–5 mm, n | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 23 | 2/2 (100%) | 1/2 (50%) | N/A | 3/10 (30%) | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0.15 |

| B | 23 | N/A | 3/3 (100%) | 5/6 (83%) | 10/30 (33%) | 0 | 1b | 9 | |

| C | 23 | N/A | 1/1 (100%) | 2/2 (100%) | 6/20 (30%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| D | 20 | N/A | 3/3 (100%) | 2/4 (50%) | 4/12 (33%) | 1c | 1 | 2 | |

| Overall | 89 | 2/2 (100%) | 8/9 (89%) | 9/12 (75%) | 23/72 (32%) | 1 | 3 | 19 |

N/A Not applicable

aComparison of false positives across regimens using one-way ANOVA

bIn patient with confirmed 8-mm polyp

cIn patient with confirmed 10-mm polyp

Fig. 6.

A 54-year-old male with change in bowel habit. Axial CT colonographic image of a 6-mm filling defect in the rectum reported as a polyp. No lesion was found at colonoscopy with segmental unblinding suggesting the lesion was untagged faecal residue

Fig. 7.

Overall number of false positives according to size and regimen (n = 89)

Per patient analysis

Across all regimens sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values for detection of patients with any lesion ≥6 mm were 96%, 97%, 0.9 and 0.96 respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Per-patient performance overall and according to tagging regimen

| Regimen | Patient number | Polyp ≥6 mm incl. cancer, n (%) [95% confidence limits] | Polyp ≥10 mm incl. cancer, n (%) [95% confidence limits] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | ||

| A | 23 | 3/4 (75%) [33–100%] | 18/19 (95%) [85–100%] | 0.75 | 0.95 | 3/4 (75%) [33–100%] | 19/19 (100%) [100–100%] | 1.0 | 0.95 |

| B | 23 | 7/7 (100%) [100–100%] | 16/16 (100%) [100–100%] | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3/3 (100%) [100–100%] | 20/20 (100%) [100–100%] | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| C | 23 | 3/3 (100%) [100–100%] | 20/20 (100%) [100–100%] | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1/1 (100%) [100–100%] | 22/22 (100%) [100–100%] | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| D | 20 | 5/7 (71%) [38–100%] | 12/13 (93%) [78–100%] | 0.83 | 0.86 | 3/3 (100%) [100–100%] | 17/17 (100%) [100–100%] | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Overall | 89 | 18/21 (96%) [93–100%] | 66/68 (97%) [93–100%] | 0.9a | 0.96 | 10/11 (91%) [74–100%] | 78/78 (100%) [100–100%] | 1.0b | 0.99 |

NPV Negative predictive value, PPV positive predictive value

aPrevalence of abnormality = 0.24

bPrevalence of abnormality = 0.12

Reader confidence

The mean segmental observer confidence for excluding a polyp ≥6 mm was 90, 89, 97 and 93% for regimens A to D respectively. There was no significant difference among the regimens, either overall or in the proximal/distal colon (P = 0.15–0.57).

Discussion

In accordance with previous studies [6, 8, 10], we found patients in general preferred reduced preparation to the full purgation required for colonoscopy, although this preference was much less than expected (only 61% preferred the reduced preparation). We defined the laxation used as “reduced” in comparison to the endoscopic preparation used at our institutions which includes an additional 18 g of magnesium citrate. We also used senna rather than bisacodyl as used by Lefere et al. [9]. Both are stimulant laxatives with a similar mode of action and effect at the doses administrated, although senna was preferred as it is widely used at our institutions. However a combination of 13 g of senna and 18 g magnesium citrate clearly produces relatively strong purgation, reflected in the induced symptoms (77% of patients opened their bowels over five times) and marginal patient preference. It would therefore seem reasonable to study reduced laxation further, perhaps omitting the senna and/or reducing the dose of magnesium citrate. It is however important to realise that whereas normally patients took no solids by mouth for 24 h prior to colonoscopy, in the present study they were permitted to eat from a low-residue diet kit, an issue we did not specifically address with our questionnaires, thereby potentially underestimating this benefit.

Recent data have questioned whether CTC is actually better tolerated than conventional colonoscopy [18], but because full bowel purgation is often cited by patients as the worst part of any colonic examination [1, 2], it is assumed that reduced laxative CTC will improve patient compliance (notably in a screening setting). However this assumption has not been proven in prospective trials, and we cannot extrapolate the preferences we found into increased compliance with CTC. Indeed it could be argued the laxative regimen we used would have relative little impact on compliance in a screening setting, given the side-effect profile.

The overall quality of bowel preparation was good, with all four regimens producing at least 76% of segments with either no or scattered residue only. This is similar to data reported by Lefere et al. [9], who combined 16.5 g of magnesium citrate with biscodyl tablets and suppository. Interestingly, regimen D, which included 15 ml meglumine amidotrizoate, resulted in significantly better preparation than the other regimens, possibility due to a “washing effect” of the iodine-based contrast, incorporating solid residue into a more fluid solution [10]. Although we used a small dose, meglumine amidotrizoate is also known to have a laxative effect that may also have added to the superior cleansing.

Tagging of solid residue was in general good, with no significant difference between the regimens tested. This suggests barium-based tagging can be simplified to a 1-day regimen only, when combined with reduced cathartic preparation. Similarly all regimens produced an average tagged fluid density of around 500 HU. Recent phantom data suggest that although submerged polyp conspicuity is optimised at 700 HU, it remains good at 500 HU [19]. We did however demonstrate that fluid tagging could be manipulated by additional oral agents on the morning of CTC. As it is non-miscible with water, barium often produces a layering effect with lower attenuation fluid sitting above denser barium. Although there was no significant difference in layering among the regimens, the addition of morning 2.1% barium sulphate or meglumine amidotrizoate significantly increased the attenuation of the non-dependent fluid layer. It is arguable whether this will have significant impact clinically, not least because fluid moves between supine and prone positions, but it may have implications for subtraction software. Zalis et al. have recently demonstrated suboptimal subtraction when high-density barium is used as the sole tagging agent [10]. It is interesting to speculate whether manipulation of fluid tagging could optimise subtraction. It should also be noted our regimen mildly restricted fluid intake the day prior to CTC, which may have influenced our fluid tagging results.

One major advantage of barium as a tagging agent is its inert nature and safety. Although iodinated contrast medium produces more homogeneous fluid tagging, this is mainly of clinical importance if subtraction software is being used. While the risks of allergy to oral iodinated contrast are minimal, adverse events do occur [20, 21]. Our data suggest good results can be achieved using only barium.

Ultimately, diagnostic performance is the best measure of the success of any reduced-laxative protocol. Reassuringly overall, we prospectively found high diagnostic performance when compared to colonoscopy. Our data confirm again that full bowel preparation is not required to maintain diagnostic accuracy for CTC, assuming adequate reader training [22]. Importantly, there were only four false positive polyps over 6 mm, and across all regimens the positive predictive value for patients with any lesion ≥6 mm and ≥10 mm was 0.9 and 1.0 respectively (Table 5).

Our study does have weaknesses. It could be argued that we used a relatively harsh laxative regime given that good results have been reported without any laxative at all [5, 6]. However the vast majority of CTC worldwide is still performed using full bowel preparation, and in the authors’ opinion, significant changes in practice are most likely to follow gradual reduction of purgation, which allows radiologists to become comfortable with this approach. However we acknowledge that if there was good evidence of acceptable performance data using CTC without prior laxation, this may well rapidly become widely implemented by the CTC community. We compared patient symptomatology with a historical cohort, and although well-matched in demographic terms, we cannot exclude bias completely. We did not instruct colonoscopists to grade the quality of bowel preparation and, in particular, the influence of retained barium on mucosal visibility, although no endoscopy failed due to incomplete bowel preparation. It could be argued that reduced preparation regimens are best suited to increase compliance in asymptomatic screening populations [23]. However for pragmatic reasons we used symptomatic patients, as we do not have access to a large screening population. Finally, although we were able to show high diagnostic performance for reduced-preparation CTC overall, given the relatively low number of polyps, we were unable to meaningfully compare across regimens.

In conclusion, a combination of reduced laxatives and a simple tagging regimen based on 40% barium sulphate the day prior to CTC maintains acceptable diagnostic accuracy. Three doses of 20 ml 40%w/v barium sulphate are as effective as more complex regimens, but fluid tagging can be manipulated by addition of dilute barium or meglumine amidotrizoate on the morning of CTC, the latter also reducing the volume of residual stool.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by an educational grant from EZEM, Lake Success, NY, and by a pump-priming grant from the Royal College of Radiologists, London, UK.

References

- 1.Ristvedt SL, McFarland EG, Weinstock LB, Thyssen EP (2003) Patient preferences for CT colonography, conventional colonoscopy, and bowel preparation. Am J Gastroenterol 98:578–585 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Thomeer M, Bielen D, Vanbeckevoort D, Dymarkowski S, Gevers A, Rutgeerts P, Hiele M, Van Cutsem E, Marchal G (2002) Patient acceptance for CT colonography: what is the real issue? Eur Radiol 12:1410–1415 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gluecker TM, Johnson CD, Harmsen WS, Offord KP, Harris AM, Wilson LA, Ahlquist DA (2003) Colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography, colonoscopy, and double-contrast barium enema examination: prospective assessment of patient perceptions and preferences. Radiology 227:378–384 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Heymann TD, Chopra K, Nunn E, Coulter L, Westaby D, Murray-Lyon IM (1996) Bowel preparation at home: prospective study of adverse effects in elderly people. BMJ 313:727–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Lefere P, Gryspeerdt S, Baekelandt M, Van Holsbeeck B (2004) Laxative-free CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 183:945–948 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Iannaccone R, Laghi A, Catalano C, Mangiapane F, Lamazza A, Schillaci A, Sinibaldi G, Murakami T, Sammartino P, Hori M, Piacentini F, Nofroni I, Stipa V, Passariello R (2004) Computed tomographic colonography without cathartic preparation for the detection of colorectal polyps. Gastroenterology 127:1300–1311 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Callstrom MR, Johnson CD, Fletcher JG, Reed JE, Ahlquist DA, Harmsen WS, Tait K, Wilson LA, Corcoran KE (2001) CT colonography without cathartic preparation: feasibility study. Radiology 219:693–698 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Lefere PA, Gryspeerdt SS, Dewyspelaere J, Baekelandt M, Van Holsbeeck BG (2002) Dietary fecal tagging as a cleansing method before CT colonography: initial results—polyp detection and patient acceptance. Radiology 224:393–403 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lefere P, Gryspeerdt S, Marrannes J, Baekelandt M, Van Holsbeeck B (2005) CT colonography after fecal tagging with a reduced cathartic cleansing and a reduced volume of barium. AJR Am J Roentgenol 184:1836–1842 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Zalis ME, Perumpillichira JJ, Magee C, Kohlberg G, Hahn PF (2006) Tagging-based, electronically cleansed CT colonography: evaluation of patient comfort and image readability. Radiology 239:149–159 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zalis ME, Perumpillichira J, Del Frate C, Hahn PF (2003) CT colonography: digital subtraction bowel cleansing with mucosal reconstruction—initial observations. Radiology 226:911–917 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Burling D, Taylor SA, Halligan S, Gartner L, Paliwalla M, Peiris C, Singh L, Bassett P, Bartram C (2006) Automated insufflation of carbon dioxide for MDCT colonography: distension and patient experience compared with manual insufflation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 186:96–103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, Butler JA, Puckett ML, Hildebrandt HA, Wong RK, Nugent PA, Mysliwiec PA, Schindler WR (2003) Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med 349:2191–2200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Pineau BC, Paskett ED, Chen GJ, Espeland MA, Phillips K, Han JP, Mikulaninec C, Vining DJ (2003) Virtual colonoscopy using oral contrast compared with colonoscopy for the detection of patients with colorectal polyps. Gastroenterology 125:304–310 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Atkin WS, Hart A, Edwards R, Cook CF, Wardle J, McIntyre P, Aubrey R, Baron C, Sutton S, Cuzick J, Senapati A, Northover JM (2000) Single blind, randomised trial of efficacy and acceptability of oral Picolax versus self administered phosphate enema in bowel preparation for flexible sigmoidoscopy screening. BMJ 320:1504–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Taylor SA, Halligan S, Goh V, Morley S, Atkin W, Bartram CI (2003) Optimizing bowel preparation for multidetector row CT colonography: effect of Citramag and Picolax. Clin Radiol 58:723–732 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Taylor SA, Halligan S, Goh V, Morley S, Bassett P, Atkin W, Bartram CI (2003) Optimizing colonic distention for multi-detector row CT colonography: effect of hyoscine butylbromide and rectal balloon catheter. Radiology 229:99–108 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Bosworth HB, Rockey DC, Paulson EK, Niedzwiecki D, Davis W, Sanders LL, Yee J, Henderson J, Hatten P, Burdick S, Sanyal A, Rubin DT, Sterling M, Akerkar G, Bhutani MS, Binmoeller K, Garvie J, Bini EJ, McQuaid K, Foster WL, Thompson WM, Dachman A, Halvorsen R (2006) Prospective comparison of patient experience with colon imaging tests. Am J Med 119:791–799 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Slater A, Taylor SA, Burling D, Gartner L, Scarth J, Halligan S (2006) Colonic polyps: effect of attenuation of tagged fluid and viewing window on conspicuity and measurement-in vitro experiment with porcine colonic specimen. Radiology 240:101–109 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ridley LJ (1998) Allergic reactions to oral iodinated contrast agents: reactions to oral contrast. Australas Radiol 42:114–117 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Skucas J (1997) Anaphylactoid reactions with gastrointestinal contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol 168:962–964 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Slater A, Taylor SA, Tam E, Gartner L, Scarth J, Peiris C, Gupta A, Marshall M, Burling D, Halligan S (2006) Reader error during CT colonography: causes and implications for training. Eur Radiol 16:2275–2283 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Taylor SA, Laghi A, Lefere P, Halligan S, Stoker J (2007) European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR): consensus statement on CT colonography. Eur Radiol 17:575–579 [DOI] [PubMed]