Abstract

The molecular mechanisms for plastic deformation of bone tissue are not well understood. We analysed temperature and strain-rate dependence of the tensile deformation behaviour in fibrolamellar bone, using a technique originally developed for studying plastic deformation in metals. We show that, beyond the elastic regime, bone is highly strain-rate sensitive, with an activation volume of ca 0.6 nm3. We find an activation energy of 1.1 eV associated with the basic step involved in the plastic deformation of bone at the molecular level. This is much higher than the energy of hydrogen bonds, but it is lower than the energy required for breaking covalent bonds inside the collagen fibrils. Based on the magnitude of these quantities, we speculate that disruption of electrostatic bonds between polyelectrolyte molecules in the extrafibrillar matrix of bone, perhaps mediated by polyvalent ions such as calcium, may be the rate-limiting elementary step in bone plasticity.

Keywords: bone plasticity, micromechanics of bone, deformation mechanisms, thermal activation, calcium mediated bonds

1. Introduction

Bone is fracture resistant and shows large plastic deformation (Rho et al. 1998; Fratzl et al. 2004). Little quantitative information is available on the nature of the basic molecular level rearrangements under stress, which make this irreversible plastic deformation possible. Plasticity has to do with breaking and rearrangement of bonds, and bone is not an exception. Such processes can be helped by thermal activation (Kocks et al. 1975). The question is which bonds are breaking and how. In the case of metals, for example, the elementary process is known to be associated with the movement of lattice dislocations (Kocks et al. 1975), a process not likely to occur in the protein–mineral composite bone. As plasticity is a major factor reducing bone fragility, its origin is of the highest interest, both for the fundamental understanding of biological composites as well as to assess the possible origin of age-related fracture (Zioupos 2001) occurring without apparent change in the overall mechanical properties (Zioupos & Currey 1998). Owing to the hierarchical structure of bone (Rho et al. 1998; Weiner & Wagner 1998), length-scales ranging from the tissue level at 1–100 μm (Nalla et al. 2003) to the molecular scale (Mercer et al. 2006) have been considered to be responsible for the inelastic behaviour of bone. Indeed, the majority of studies do not use plasticity concepts but rather damage models (Carter & Caler 1985; Schaffler et al. 1994; Zioupos & Currey 1994; Reilly & Currey 2000) to understand the post-yield behaviour in bone, where damage means phenomena, such as microcracking and microfractures (Zioupos & Currey 1994; Zioupos 1999), observed with confocal scanning and light microscopy techniques.

In general, plastic deformation corresponds to the opening and reforming of bonds, leading to a permanent deformation. Thermodynamically, this corresponds to a movement over local energy barriers at the molecular level—leading to creep on a macroscopic scale—and can be described as an Arrhenius-type rate process (Schoeck 1965; Gibbs 1967). For permanent plastic deformation at a stress σ and temperature T, the macroscopic strain rate dϵ/dt and the flow stress are related to each other through the microscopic activation energy barrier H and the volume v associated with the jump over the barrier, as

| (1.1) |

The magnitude of H and v, thus obtained from macroscopic mechanical tests, give insight into the nature of the deformation mechanism at the molecular level. In metals and metal alloys, the activation volume for dislocation movement v can be written in terms of the Burgers vector for the basic dislocation step (Kocks et al. 1975), and thus provides information on the nature of the dislocation mechanism (Caillard & Martin 2003). This motivates us to see whether we could, similarly, quantify experimentally the length-scale and energy barrier associated with the elementary step at the molecular level for plastic deformation in bone.

2. Material and methods

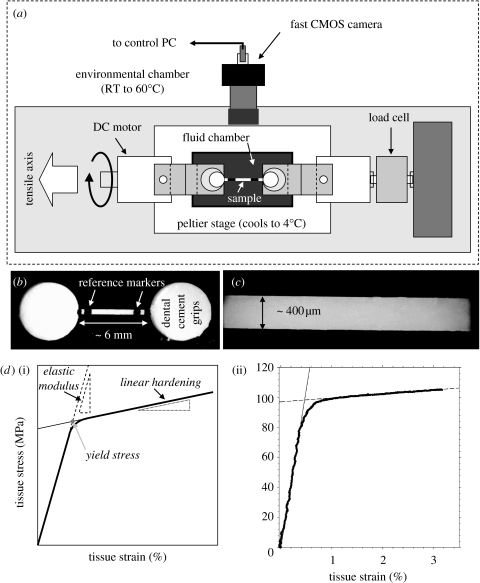

Fibrolamellar bone from the periosteum of bovine femora (Gupta et al. 2005) was stretched to failure in a specially built tensile rig which enabled temperature control, from 4 to 50°C, in saline testing to keep the bone wet, and strain rates of up to 20–50% s−1 measured with video extensometry (figure 1 and electronic supplementary material). The tensile specimens had a gauge length of 6 mm and a cross-sectional area of 0.08 mm2 on average. Strain was measured from the percentage increase in separation of two markers on the bone imaged with a video camera. Temperature was typically kept constant during the test, although for a few measurements the temperature was changed abruptly in the yield region (see electronic supplementary material).

Figure 1.

(a) Overview of the tensile test set-up. (b) Light microscope image of a test sample between two cylindrical dental glue grips. (c) Larger magnification view of the sample, showing the homogeneous structure. (d(i)) a schematic of a typical stress–strain curve, with the definitions of elastic modulus, linear hardening and yield stress indicated; (ii) a representative stress–strain curve taken with strain rate 1.5×10−4 s−1 at 16°C, showing the elastic modulus, linear hardening and yield stress.

3. Results

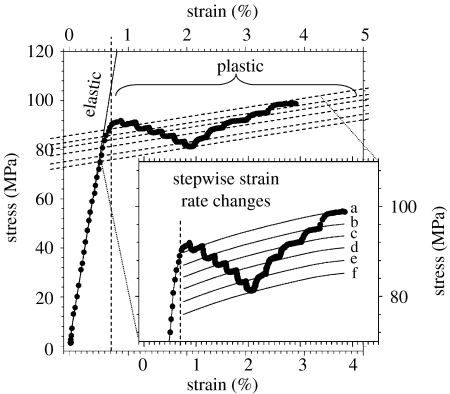

Activation volume: to measure the activation volume v of plastic deformation, bone samples were stretched at constant motor velocity into the plastic yield region as shown in figure 2. When the sample was clearly in the zone of plastic deformation, the strain rate was reduced either once or several times (figure 2, inset). This change led to a reduction of the flow stress but, interestingly, the slope of the post-yield curve (linear hardening dσ/dϵ) remained constant. From equation (1.1), the activation volume can be estimated as

| (1.2) |

Using this differential method to estimate the activation volume leads to an average value of v=1.00±0.19 nm3 (n=8, error bars: standard deviations), implying that whatever (as yet unspecified) deformation processes occur in bone plasticity, the fundamental step is confined within a nanoscale volume. The activation volume is statistically independent (p>0.05) of stress, for a range of samples studied.

Figure 2.

Measurement of the activation volume v in bone plasticity: the plot shows a uniaxial tensile test at constant temperature T=296 K with six stepwise reductions in motor velocity from 10 to 0.1 μm s−1 (a→f≡10 μm s−1→5 μm s−1→2 μm s−1→1 μm s−1→0.5 μm s−1→0.2 μm s−1→0.1 μm s−1) and subsequent increases. The differential changes in stress with differential changes in strain rate can be used to compute the activation volume (equation (1.2)).

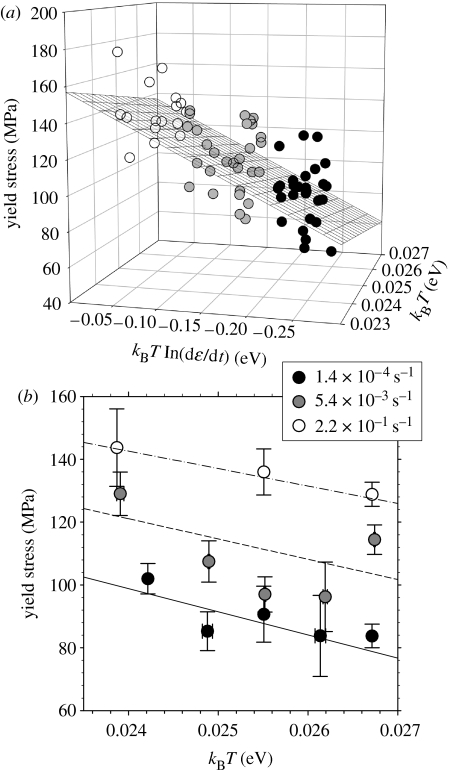

Activation enthalpy: to determine the height of the thermal activation barrier in bone deformation, numerous stretch-to-failure tests were done on bone tissue at strain rates varying from 1.4×10−4 to 2×10−1 s−1 and temperatures from 4 to 37°C (n=74 total; see table 1 in the electronic supplementary material for breakdown by strain rate and temperature). The lowest strain rates used were comparable to those previously used to measure fibrillar deformation using synchrotron radiation (Gupta et al. 2005), the intermediate strain rate was comparable to the rates obtained from physiological in vivo measurements (Robertson & Smith 1978; Burr et al. 1996) and close to strain rates of 0.6 s−1 typical for hip fractures (Courtney et al. 1996). The highest strain rates are a little below those rates at which the onset of brittle behaviour was observed (Mcelhaney 1966). For each sample, the yield stress σP was calculated as in figure 1a. Rewriting equation (1.1) as

| (1.3) |

we carried out a multiple linear regression of σP in terms of X and Y. An extremely significant (p<0.0001) correlation was found between the dependent (stress σP) and independent variables (X and Y). The resulting fit parameters are: H=1.11±0.34 eV; v=0.64±0.07 nm3; and (dϵ/dt)0=1.11×109 s−1 (3.00×106–4.09×1011 s−1), and the plane fit is shown in figure 3a. Representing our data in terms of σ–T graphs, as usual in analyses of thermally activated plasticity (Kocks et al. 1975), we show mean value and standard deviation of the yield stress for several values of temperature and strain rate in figure 3b. The yield stress decreases with increasing temperature for all the three strain rates. The broken lines show how equation (1.3) predicts that the yield stress σP would vary as a function of temperature at a given strain rate (using the fitted parameters from figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Measurement of the activation enthalpy H of bone plasticity: a set of samples (n=74) are stretched to failure in tension, at three strain rates and at least three temperatures at each strain rate, from 277 to 310 K, and the yield stress σP measured. Plot (a) shows the yield stress σP as a function of kBT and kBT ln(dϵ/dt). Black grid lines show the results of the linear plane fit . Plot (b) shows the same three-dimensional plot in the σP–kBT plane, giving the average stress (error bars: standard deviations) for a given strain rate and temperature. Lines are predictions based on model fit in (a), at the given three strain rates: dash-dotted lines and white circles≡2.2×10−1 s−1; short dashed lines and grey symbols≡5.4×10−3 s−1; solid lines and black symbols≡1.4×10−4 s−1. Note that the fact that we view (a) at an angle almost 90° to the effective viewing direction in (b) is deliberate, chosen to give the reader the perspective from two orthogonal directions.

The discrepancy between the activation volumes obtained from the global survey of yield stress data (0.64±0.07 nm3) and from the differential data of various flow stresses (1.00±0.19 nm3) is not surprising. The former refer to specimens with unmodified microstructure, at the onset of plastic deformation, the latter to microstructures already modified by plastic deformation. Such subtleties amount to strain and stress dependence of the activation volume (Kocks et al. 1975) and are beyond the concern of present bone research. We therefore take the latter value as confirmation of the former.

4. Discussion

To summarize, we find that plastic deformation in bone is characterized by a very small activation volume ν of the order of 1 nm3 and an activation enthalpy of the order of H=1.1 eV. This activation enthalpy is smaller than typical covalent bond energies (C–C bond approx. 3.6 eV) but much larger than hydrogen bonds (approx. 40 meV). The Gibbs free energy G(σ)=H−vσ is the free energy to be supplied during one activation event in the plastic deformation of bone. The applied stress σ increases the probability of the irreversible deformation occurring, by doing work against a certain basic volume of deformation v. H and v carry information on the energy barrier needed to go from the undeformed to the deformed state, but they give no information about the kinetics of this process.

The small activation volume suggests that the elementary process corresponds to the breaking of just a few spatially confined bonds. In metal plasticity, which is controlled by the dynamics of dislocations (Schoeck 1965; Gibbs 1967; Kocks et al. 1975), the activation volume is the area of slip × the Burgers vector (Kirchner 2006). In the case of bone, the small size of the activation volume is likely owing to a confinement of the soft organic matrix (which is likely to flow) between nanometre-sized particles. Size effects on mechanical properties are well known from the science of materials strength as seen, for example, in recent work (Uchic et al. 2004; Espinosa et al. 2005). Our recent in situ diffraction results (Gupta et al. 2005, 2006) suggest that after the onset of macroscopic plasticity, only elastic deformation is retained within fibrils and plastic deformation occurs between them.

The magnitude of the activation enthalpy H≅1.1 eV suggests that the bonds being broken are not likely covalent. Hydrogen bonds, having energy of 40 meV each, would have to break in large numbers (approx. 50) simultaneously to provide the necessary energy, but such a situation is inconsistent with the small activation volume of up to 1 nm3. As a consequence, the most likely types of bonds are charge interactions between molecules in the extrafibrillar space. It is not known which these molecules are, but substantial amounts of non-collageneous molecules, such as proteoglycans (Scott 1992), osteopontin (Sodek et al. 2000) or fetuin A (Heiss et al. 2003), are present in the bone matrix. These (mostly negatively) charged molecules (or any combination of them) could be responsible for forming a plastic ‘glue’ between fibrils. The existence of such a ‘glue’ has recently been proposed following force spectroscopy experiments (Thompson et al. 2001) and it was shown that the occurrence of bond breaking and reforming was related to the presence of calcium ions (Fantner et al. 2005, 2006). The energy associated with these ‘sacrificial bonds’ is consistent with the activation enthalpy of 1 eV found here (Fantner et al. 2006). Recently, it has also been shown that the deformation of polyelectrolyte capsules is associated with breaking a group of neighbouring charge interactions on polyelectrolyte segment (Leporatti et al. 2001). The activation enthalpy was shown to be ca 1 eV in this case and the activation volume (corresponding to the size of the polyelectrolyte segment) was also in the range of ca 1 nm3 (Leporatti et al. 2001). Breaking and reformation of bonds has also been found in the hemicellulose matrix between cellulose fibrils in the cell wall during plastic deformation of wood (Keckes et al. 2003).

Thermodynamics of plastic deformation interprets the pre-exponential factor (dϵ/dt)0 as a product of an attempt frequency ν0 and the deformation ϵ0 caused by each activated event. The latter quantity ϵ0 depends on the process controlling strain (dislocation density, obstacle density, etc.). It is difficult to put a precise value for the attack frequency ν0, but it must be of the order of vibrations present in the medium. The phonon spectrum of bone has never been measured, but presumably, it must be similar to the spectrum of type I collagen found in tendon (Middendorf et al. 1995). The latter shows several broad maxima between 1×1013 and 6×1013 s−1, which have been attributed to various localized modes. Given the fact that possible localized modes at the interface between fibrils must be low-frequency ones otherwise the interfacial entropy would be negative, it is not unreasonable to assume a value of ν0=1012–13 s−1. Our fit results provide a value lower than this range (1.11×109 s−1) but, unsurprisingly in light of the discussion above, this is the fit parameter that showed a substantial error (approx. 30% in the logarithm) in the multiple linear regression, leading to a possible range of values from 3.00×106 to 4.09×1011 s−1.

Damage has been associated with the post-yield behaviour, but the nature of the damage is unclear (Carter & Caler 1985; Schaffler et al. 1994; Zioupos & Currey 1994; Zioupos et al. 1994; Zioupos 1999; Reilly & Currey 2000). The damage is believed to be related to the formation of microcracks or smaller defects at weak interfaces such as between old and new bone packets in trabecular bone, between lamellae in lamellar cortical bone or between osteons and interstitial bone (Lakes & Saha 1979; Braidotti et al. 2000; Diab et al. 2006; Peterlik et al. 2006). In the present work, we try to avoid the effect of these weak interfaces, both by preparing samples whose cross-section is of the order of the width of single fibrolamellar bone packets (see electronic supplementary material) and by studying this relatively parallel fibred tissue in tension. Nevertheless, the breaking of bonds (within an activation volume of ca 1 nm3) can be regarded as damage at the supramolecular level which has, however, the capability of self-healing by the reformation of the bonds. An indication that this is the case is seen in cyclic tensile loading of our samples in the inelastic regime (figure S6 in electronic supplementary material). The initial slopes of the loading segments are similar, indicating recovery at the material level. However, the progressively lower yield stress for successive cycles implies that the recovery may be incomplete, due to damage at the nanoscale level. As such, the post-yield behaviour reported here has more resemblance to plastic deformation in metals than to damage as observed in many composite materials.

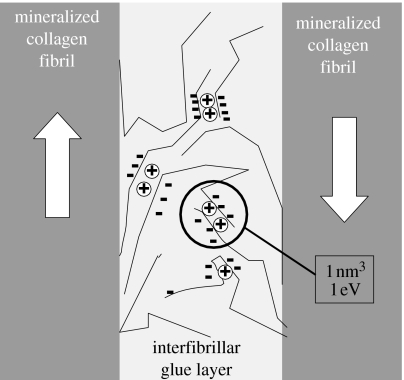

The results of this paper are in excellent agreement with the previous work showing that the deformation in bone might be associated with (calcium-dependent) sacrificial bonds (Thompson et al. 2001; Fantner et al. 2005, 2006) and with independent work demonstrating that the plastic deformation occurs in a thin ‘glue’ layer between fibrils (Gupta et al. 2005, 2006). The picture which emerges is that plastic deformation is controlled by an elementary process where segments of molecules in the interfibrillar layer are connected by charge interactions with a total energy of 1 eV in a volume of 1 nm3 (corresponding to the volume of the rigid molecular segments which move in a coordinated fashion). These results are summarized in the model drawn in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Bond breaking within the thin extrafibrillar matrix (glue layer) between mineralized fibrils controls bone plasticity, based on results in this work as well as previous papers proposing deformation by sacrificial bonds (Thompson et al. 2001; Fantner et al. 2005; Hansma et al. 2005) and demonstrating a shear deformation of the glue layer (Gupta et al. 2005). Long chains of molecules (possibly negatively charged polyelectrolytes like osteopontin (Sodek et al. 2000), fetuin A (Heiss et al. 2003) or proteoglycans (Scott 1992), or combinations of those) are interacting by charges, probably with the help of cations such as calcium (circles). Charges located on a given segment will have to be broken together giving rise to the observed activation enthalpy of ca 1 eV within a typical volume of 1 nm3. The arrows indicate the movement of the collagen fibrils giving rise to shear in the matrix layer (Gupta et al. 2005). Mineral particles are not explicitly drawn, but present in the fibrils as well as in the interfibrillar space.

In conclusion, our mechanical tests on bone established a high sensitivity of the macroscopic plastic deformation to the strain rate and temperature. By putting our results in the scheme of thermally activated processes controlling bone plasticity, quantitative results can be obtained on the length-scale and energy associated with bone plasticity mechanisms at the molecular level. The fundamental processes involved in plastic deformation are localized to within 1 nm3, and with energy of the order of 1 eV. We speculate that these processes are localized in a small fraction of the bone tissue—the extrafibrillar matrix—and correspond to the disruption of calcium-mediated ionic bonds between the long and irregular chains of molecules constituting this matrix.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Leibner, A. M. Martins, W. Nierenz and H. Pitas from the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces, and P. Bennett from Vector International (Leuven, Belgium) for technical assistance, and the Max Planck Society for support.

Supplementary Material

Here we give an overview of the experimental setup for tensile testing of wet fibrolamellar bone in a temperature range 4° to 50°C. The video extensometry procedure used to measure the strain in a non - contact method is described, including the special procedure used for high strain rates (<10 % s-1). In addition, representative cyclic tensile loading curves are shown, to demonstrate similar values of loading and reloading slopes

References

- Braidotti P, Bemporad E, D'alessio T, Sciuto S.A, Stagni L. Tensile experiments and SEM fractography on bovine subchondral bone. J. Biomech. 2000;33:1153–1157. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(00)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr D.B, Milgrom C, Fyhrie D, Forwood M, Nyska M, Finestone A, Hoshaw S, Saiag E, Simkin A. In vivo measurement of human tibial strains during vigorous activity. Bone. 1996;18:405–410. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillard D, Martin J.L. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2003. Thermally activated mechanisms in crystal plasticity. [Google Scholar]

- Carter D.R, Caler W.E. A cumulative damage model for bone-fracture. J. Orthop. Res. 1985;3:84–90. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100030110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney A.C, Hayes W.C, Gibson L.J. Age-related differences in post-yield damage in human cortical bone. Experiment and model. J. Biomech. 1996;29:1463–1471. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)84542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diab T, Condon K.W, Burr D.B, Vashishth D. Age-related change in the damage morphology of human cortical bone and its role in bone fragility. Bone. 2006;38:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa H.D, Berbenni S, Panico M, Schwarz K.W. An interpretation of size-scale plasticity in geometrically confined systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16 933–16 938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508572102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantner G, et al. Sacrificial bonds and hidden length dissipate energy as mineralized fibrils separate during bone fracture. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:612–616. doi: 10.1038/nmat1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantner G.E, et al. Sacrificial bonds and hidden length: unraveling molecular mesostructures in tough materials. Biophys. J. 2006;90:1411–1418. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratzl P, Gupta H.S, Paschalis E.P, Roschger P. Structure and mechanical quality of the collagen-mineral nano-composite in bone. J. Mater. Chem. 2004;14:2115–2123. doi: 10.1039/b402005g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs G.B. Activation parameters for dislocation glide. Philos. Mag. 1967;16:97. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta H.S, Wagermaier W, Zickler G.A, Aroush D.R.B, Funari S.S, Roschger P, Wagner H.D, Fratzl P. Nanoscale deformation mechanisms in bone. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2108–2111. doi: 10.1021/nl051584b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta H.S, Wagermaier W, Zickler G.A, Hartmann J, Funari S.S, Roschger P, Wagner H.D, Fratzl P. Fibrillar level fracture in bone beyond the yield point. Int. J. Fract. 2006;139:425–436. doi: 10.1007/s10704-006-6635-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansma P.K, Fantner G.E, Kindt J.H, Thurner P.J, Schitter G, Udwin S.F, Finch M.M. Sacrificial bonds in the interfibrillar matrix of bone. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal. Interact. 2005;5:313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss A, Duchesne A, Denecke B, Grotzinger J, Yamamoto K, Renne T, Jahnen-Dechent W. Structural basis of calcification inhibition by alpha(2)-HS glycoprotein/fetuin-A—formation of colloidal calciprotein particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:13 333–13 341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keckes J, et al. Cell-wall recovery after irreversible deformation of wood. Nat. Mater. 2003;2:810–814. doi: 10.1038/nmat1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner H.O.K. Dislocations in bone. Int. J. Fract. 2006;139:509. doi: 10.1007/s10704-006-0050-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kocks U.F, Argon A.S, Ashby M.F. Pergamon Press; Oxford, UK: 1975. Thermodynamics and kinetics of slip. [Google Scholar]

- Lakes R, Saha S. Cement line motion in bone. Science. 1979;204:501–503. doi: 10.1126/science.432653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leporatti S, Gao C, Voigt A, Donath E, Mohwald H. Shrinking of ultrathin polyelectrolyte multilayer capsules upon annealing: a confocal laser scanning microscopy and scanning force microscopy study. Eur. Phys. J. E. 2001;5:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s101890170082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mcelhaney J. Dynamic response of bone and muscle tissue. J. Appl. Physiol. 1966;21:1231. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.4.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer C, He M.Y, Wang R, Evans A.G. Mechanisms governing the inelastic deformation of cortical bone and application to trabecular bone. Acta Biomater. 2006;2:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middendorf H.D, Hayward R.L, Parker S.F, Bradshaw J, Miller A. Vibrational neutron spectroscopy of collagen and model polypeptides. Biophys. J. 1995;69:660–673. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79942-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalla R.K, Kinney J.H, Ritchie R.O. Mechanistic fracture criteria for the failure of human cortical bone. Nat. Mater. 2003;2:164–168. doi: 10.1038/nmat832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterlik H, Roschger P, Klaushofer K, Fratzl P. From brittle to ductile fracture of bone. Nat. Mater. 2006;5:52–55. doi: 10.1038/nmat1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly G.C, Currey J.D. The effects of damage and microcracking on the impact strength of bone. J. Biomech. 2000;33:337–343. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho J.Y, Kuhn-Spearing L, Zioupos P. Mechanical properties and the hierarchical structure of bone. Med. Eng. Phys. 1998;20:92–102. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4533(98)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D.M, Smith D.C. Compressive strength of mandibular bone as a function of microstructure and strain rate. J. Biomech. 1978;11:455–471. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(78)90057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffler M.B, Pitchford W.C, Choi K, Riddle J.M. Examination of compact-bone microdamage using backscattered electron-microscopy. Bone. 1994;15:483–488. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeck G. Activation energy of dislocation movement. Phys. Status Solidi. 1965;8:499. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J.E. Supramolecular organization of extracellular-matrix glycosaminoglycans. In vitro and in the tissues. FASEB J. 1992;6:2639–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodek J, Ganss B, Mckee M.D. Osteopontin. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2000;11:279–303. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.B, Kindt J.H, Drake B, Hansma H.G, Morse D.E, Hansma P.K. Bone indentation recovery time correlates with bond reforming time. Nature. 2001;414:773–776. doi: 10.1038/414773a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchic M.D, Dimiduk D.M, Florando J.N, Nix W.D. Sample dimensions influence strength and crystal plasticity. Science. 2004;305:986–989. doi: 10.1126/science.1098993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner S, Wagner H.D. The material bone: structure mechanical function relations. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1998;28:271–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.matsci.28.1.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zioupos P. On microcracks, microcracking, in-vivo, in-vitro, in-situ and other issues. J. Biomech. 1999;32:209–211. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(98)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zioupos P. Ageing human bone: factors affecting its biomechanical properties and the role of collagen. J. Biomater. Appl. 2001;15:187–229. doi: 10.1106/5JUJ-TFJ3-JVVA-3RJ0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zioupos P, Currey J.D. The extent of microcracking and the morphology of microcracks in damaged bone. J. Mater. Sci. 1994;29:978–986. doi: 10.1007/BF00351420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zioupos P, Currey J.D. Changes in the stiffness, strength, and toughness of human cortical bone with age. Bone. 1998;22:57–66. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zioupos P, Currey J.D, Sedman A.J. An examination of the micromechanics of failure of bone and antler by acoustic-emission tests and laser-scanning-confocal-microscopy. Med. Eng. Phys. 1994;16:203–212. doi: 10.1016/1350-4533(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Here we give an overview of the experimental setup for tensile testing of wet fibrolamellar bone in a temperature range 4° to 50°C. The video extensometry procedure used to measure the strain in a non - contact method is described, including the special procedure used for high strain rates (<10 % s-1). In addition, representative cyclic tensile loading curves are shown, to demonstrate similar values of loading and reloading slopes