Abstract

Objective

Quality of life (QOL) is considered an important outcome in the treatment of schizophrenia, but the determinants of QOL are poorly understood in this population. Furthermore, previous studies have relied on combined measures of subjective QOL (usually defined as life satisfaction) and objective QOL (usually defined as participation in activities and relationships). We examined separately the clinical, functional, and cognitive predictors of subjective and objective QOL in outpatients with schizophrenia. We hypothesized that better subjective QOL would be associated with less severe negative and depressive symptoms, better objective QOL, and greater everyday functioning capacity, and that better objective QOL would be associated with less severe negative and depressive symptoms, better cognitive performance, and greater functional capacity.

Method

Participants included 88 outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who completed a comprehensive series of assessments, including measures of positive, negative, and depressive symptoms; performance-based functional skills; a neuropsychological battery; and an interview measure of subjective and objective QOL.

Results

In the context of multiple predictor variables, more severe depressive symptoms and better neuropsychological functioning were independent predictors of worse subjective QOL. More severe negative symptoms predicted worse objective QOL. Functional capacity variables were not associated with subjective or objective QOL.

Conclusion

Treatments to improve QOL in schizophrenia should focus on negative symptoms and depressive symptoms.

Keywords: psychotic disorders, cognition, neuropsychology, social support, depression

1. Introduction

Subjective well-being and quality of life (QOL) are increasingly being recognized as important treatment outcomes in patients with schizophrenia (Hofer et al., 2005b; Ruggeri et al., 2005). Until recently, treatments for schizophrenia have focused mainly on reducing positive symptoms, often leaving patients with numerous residual difficulties, including negative symptoms and impairment in cognition, everyday living skills, and social/occupational functioning. More comprehensive treatments are needed, and it makes sense that improved QOL should be a primary treatment goal. However, the predictors of QOL in schizophrenia are not well understood. Although no universal definition of QOL exists, the construct usually includes subjective well-being and objective mental and physical functioning indicators (Lehman, 1983b; Norman et al., 2000; Bow-Thomas et al., 1999; Voruganti et al., 1998; Russo et al., 1997; Lambert and Naber, 2004). Subjective QOL focuses on life satisfaction, whereas “objective” QOL focuses on participation in activities and interpersonal relationships. Although some conceptualizations hold that QOL is always purely subjective, we have adopted Lehman’s use of the terms “subjective” and “objective” QOL (Lehman, 1988) as a way to differentiate subjective life satisfaction from observable QOL indicators. Although Harvey and colleagues suggest that patients’ self-report of functional capacity may be problematic (Harvey, Velligan, & Bellack, 2007), other research demonstrates that self-report measures of QOL are more valid than clinician-report QOL measures, and that QOL can be rated accurately and consistently by patients (Voruganti et al., 1998; Becchi et al., 2004).

1.1 Predictors of Subjective QOL

Lower everyday functioning capacity and greater severity of positive, negative, and depressive symptoms have been associated with worse QOL (Hofer et al., 2005b; Norman et al., 2000; Palmer et al., 2002; Sciolla et al., 2003; Corrigan & Buican, 1995; Jin et al., 2001; Ruggeri et al., 2005; Twamley et al., 2002). Although such psychiatric symptoms have been associated with subjective measures of QOL (Hofer et al., 2005b; Ruggeri et al., 2005; Norman et al., 2000; Corrigan and Buican, 1995), symptom reductions alone often do not result in meaningful improvements in QOL because other problems remain (e.g., difficulty with everyday functioning, lack of social contacts, unemployment, and stigmatization).

Cognitive abilities are associated with functional capacity and community outcomes (Evans et al., 2003; Twamley et al., 2002; Patterson et al., 2001; Green and Nuechterlein, 1999; Green, 1996; Green et al., 2000), and may also affect life satisfaction. Poorer cognitive performance and self-reported functional status (e.g., unmarried, lower social functioning, smaller social support network) are correlated with lower subjective QOL (Corrigan and Buican, 1995; Norman et al., 2000; Lehman et al., 1983a). On the other hand, better cognitive abilities may translate into better insight, more depression, and lower subjective well-being. Demographic and clinical characteristics also influence subjective QOL, with women and those with less education, longer illness duration, and higher antipsychotic dosages reporting greater life satisfaction (Hofer et al., 2005b; Ruggeri et al., 2005; Corrigan and Buican, 1995). The link between greater illness severity and better subjective QOL may be due partially to the effects of impaired insight (Karow and Pajonc, 2006).

1.2 Predictors of Objective QOL

Patients’ self-reports of everyday functioning and activities have also been used to assess objective QOL and are distinct from self-reports of overall life satisfaction (Lehman, 1983b). Indicators of objective QOL include living situation, marital status, employment status, driving status, and involvement in social activities. Generally, patients with less severe psychiatric symptoms and better cognitive performance report better outcomes on objective QOL indicators (Hofer et al., 2005b; Palmer et al., 2002; Sciolla et al., 2003; Jin et al., 2001; Ruggeri et al., 2005). Performance-based functional capacity also has been found to predict objective QOL, particularly in terms of driving and living independence (Palmer et al., 2002; Twamley et al., 2002).

1.3 The Current Study

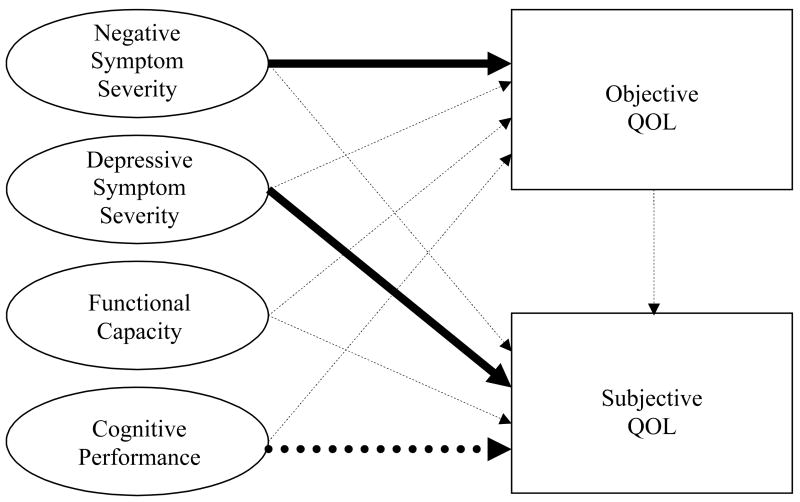

The present study aimed to identify predictors of subjective and objective QOL in outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. To our knowledge, no studies have simultaneously examined the clinical, functional, and cognitive predictors of both subjective and objective QOL in this population. In the current study, we used an extensive interview measure that evaluates subjective and objective QOL separately (the Quality of Life Interview; Lehman, 1988). Furthermore, unlike previous work, we used a performance-based measure of functional capacity (the UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment; Patterson et al., 2001) because many individuals with schizophrenia are not accurate raters of their own community functioning abilities (Bowie et al., 2006). This instrument goes beyond asking about activity participation (i.e., objective QOL) by having the examinee perform tasks necessary for independent living (e.g., grocery shopping, paying a bill, and planning a bus route). We also administered a comprehensive neuropsychological battery, rather than relying on cognitive screening measures. Our hypotheses, guided by previously published results, were that 1) greater subjective QOL would be associated with less severe negative and depressive symptoms, better functional status on objective QOL indicators, and greater performance-based functional capacity, and 2) better objective QOL would be associated with less severe negative and depressive symptoms, better cognitive performance, and greater functional capacity (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationships between Symptom Severity, Functional Capacity, and Cognitive Performance.

Note. Dashed arrows represent hypothesized relationships that were not supported in the multivariate analyses. Solid arrows represent hypothesized relationships that were supported in the multivariate analyses. The dotted arrow represents an unexpected significant relationship (worse cognitive performance was associated with better subjective QOL). Note that although the arrows depict hypothesized causative relationships, many relationships may be bidirectional.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants included 88 outpatients with DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Diagnoses were made by the treating psychiatrist and confirmed via diagnostic chart reviews by trained research staff using DSM-IV criteria. Individuals with substance abuse or dependence within the past month and those with dementia, loss of consciousness >30 minutes, or other neurological disorders were excluded from the study.

2.2 Procedure

All subjects were enrolled in psychosocial treatment studies involving cognitive training or work rehabilitation and provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the IRB and carried out in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki. Assessments of psychiatric symptom severity, performance-based functional capacity, neuropsychological performance, and subjective and objective QOL were administered to all participants at the baseline assessment, before any treatment was provided, by examiners trained to a high level of interrater reliability (ICCs>.90). Antipsychotic medication dosages were converted into chlorpromazine equivalents (CPZE) according to standard formulae (Jeste and Wyatt, 1982; Woods, 2003), except for participants taking clozapine or long-acting injectable medications (n=10), for which conversion formulae do not exist.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Clinical

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1967) assessed severity of positive, negative, and depressive symptoms. The PANSS and HAM-D were always administered first, so the ratings would not be influenced by performance or responses on subsequent measures.

2.3.2. Functional Capacity Assessment

The UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA; Patterson et al., 2001), a 30-minute measure using role-play tasks, was used to assess functional capacity in five areas: Recreational Activity Planning (e.g., planning outings); Financial Management (e.g., counting change and writing checks to pay bills); Communication (e.g., using a telephone for emergency and non-emergency purposes); Transportation Planning (e.g., using a public transportation system); and Household Chores (e.g., preparing a shopping list when given a recipe and shopping for items in a mock grocery store). Skills reflect general abilities necessary for independent community living. The total summary score and subscale scores were calculated as the percentage of items correct.

2.3.3. Neuropsychological Test Battery

Premorbid verbal intellectual functioning was assessed using the American National Adult Reading Test (ANART; Grober and Sliwinski, 1991). A global neuropsychological Z-score was calculated from mean Z-scores in four cognitive domains that are impaired in schizophrenia and are related to community functioning outcomes (Green et al., 2000; Heaton et al., 1994; Heinrichs and Zakzanis, 1998): Information processing speed (Trail Making Test, Part A [Reitan and Wolfson, 1993], WAIS-III Symbol Search and Digit Symbol subtests [Wechsler, 1997a]); Working memory (WAIS-III Letter Number Sequencing and Digit Span Backward subtests [Wechsler, 1997a]); Learning (Learning scores from the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised [Benedict et al., 1998], WMS-III Logical Memory [Wechsler, 1997b], and Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised [Benedict, 1997]); and Executive functioning (Trail Making Test, Part B minus Part A [Reitan and Wolfson, 1993], Wisconsin Card Sorting Test-64 card version [Kongs et al., 2000], Stroop Color-Word Interference Test interference measure [Golden, 1978], Letter Fluency [Benton and Hamsher, 1989]).

2.3.4. Quality of Life

The Quality of Life Interview (QOLI; Lehman, 1988) assessed QOL within the past week globally and within eight domains: living situation, daily activities and functioning, family relations, social relations, finances, work and school, legal and safety issues, and health. Subjective QOL was measured as the mean of the two global life satisfaction items regarding “life in general” as rated on 1–7 scale ranging from “terrible” to “delighted.” Three domains of objective QOL were selected for examination in this study, based on their convergent validity (Lehman et al., 1993) and relevance to everyday functioning: daily activities and functioning (e.g., going for a walk, going to a movie, shopping, reading, playing cards, preparing a meal, working on a hobby, going to the library); family relations (e.g., visiting or talking with family members); and social relations (e.g., visiting or talking with close friends). Z-scores within each of these domains were calculated, and the mean of these Z-scores was used as a global indicator of objective QOL.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

All variables were checked for normality of distribution. One variable (antipsychotic dosage in CPZE) required a log transformation to normalize it. Data from schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder patients were analyzed together, as the two groups did not differ statistically on any of the measured variables except the HAM-D (schizoaffective disorder participants reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than did those with schizophrenia). Pearson correlations and Spearman’s rho were used to test associations between the variables of interest. We also performed simultaneous entry multiple linear regression analyses to identify predictors of subjective and objective QOL. To limit the number of predictors, only variables having bivariate correlations with each dependent variable at a p<.05 level were included in the multivariate analyses.

3. Results

Sample characteristics are reported in Table 1. Most participants were middle-aged, male, Caucasian, and had a high school education. Most participants were unemployed (94%) and had never been married (56%); 35% were divorced, separated, or widowed, and 9% were currently married. Many participants (49%) lived with a roommate, family member, or romantic partner, 33% lived alone, 14% lived in a board-and-care facility or assisted living facility, and 4% were homeless. On average, the participants reported a subjective QOL rating of 4.1, approximately at the midpoint of the 1–7 scale, similar to ratings of 4.1–4.2 for chronically hospitalized patients with severe mental illnesses (Lehman et al., 1986).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 88)

| Variable | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 47.1 | 8.8 | |

| Education, years | 12.8 | 2.4 | |

| % Male | 67.0 | ||

| % Caucasian | 65.9 | ||

| % Schizophrenia (vs. schizoaffective disorder) | 42.0 | ||

| Duration of illness, years (n = 87) | 21.9 | 11.3 | |

| Antipsychotic medication regimen | |||

| None | 8.0 | ||

| Atypicals only | 80.7 | ||

| Typicals only | 5.7 | ||

| Both atypicals and typicals | 5.7 | ||

| Antipsychotic medication dose, mg CPZE (n = 78) | 318.1 | 339.7 | |

| PANSS positive symptom severity | 16.2 | 6.0 | |

| PANSS negative symptom severity | 15.1 | 5.2 | |

| HAM-D depressive symptom severity (n = 87) | 10.9 | 6.6 | |

| ANART verbal intellectual functioning estimate | 109.0 | 10.4 | |

| UPSA total (n = 86) | 83.3 | 10.0 | |

| Subjective QOL (mean global life satisfaction score) | 4.1 | 1.5 | |

Partially supporting the first hypothesis, we found that worse subjective QOL was strongly associated with more severe depressive symptoms (see Table 2). However, the correlation between subjective QOL and negative symptom severity and the correlation between subjective and objective QOL were not significant. Contrary to expectation, subjective QOL was not associated with any UPSA score. Worse subjective QOL was associated with being female, having schizoaffective disorder rather than schizophrenia, and with better cognitive performance.

Table 2.

Associations between QOL and demographic, clinical, functional capacity, and neuropsychological variables

| Subjective QOL | Objective QOL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ra | P | ra | p |

| Age, years | .04 | .723 | −.23 | .032* |

| Education, years | −.08 | .443 | .26 | .015* |

| Gender (0 = female, 1 = male) | .23 | .035* | −.04 | .741 |

| Ethnic minority status (0 = Caucasian, 1 = minority) | .06 | .568 | −.09 | .431 |

| Diagnosis (0 = schizophrenia, 1 = schizoaffective disorder) | −.24 | .023* | .15 | .177 |

| Duration of illness, years | .08 | .440 | −.06 | .568 |

| Antipsychotic medication dose, mg CPZE | −.10 | .427 | .14 | .262 |

| PANSS positive symptom severity | −.17 | .114 | −.16 | .134 |

| PANSS negative symptom severity | −.20 | .066 | −.49 | <.001* |

| HAM-D depressive symptom severity | −.53 | <.001* | −.18 | .091 |

| UPSA Recreation Planning | .11 | .292 | −.02 | .874 |

| UPSA Financial Management | −.03 | .773 | .20 | .064 |

| UPSA Communication | −.12 | .255 | .20 | .069 |

| UPSA Transportation Planning | .02 | .892 | .11 | .323 |

| UPSA Household Chores | .01 | .958 | .15 | .159 |

| Neuropsychological Z-score | −.24 | .030* | .23 | .036* |

| Objective QOL | .18 | .091 | -- | -- |

Spearman correlation and associated p-value used for nominal independent variables; all other values are Pearson correlations

p < .05; included in multiple regression analyses (see Table 3)

Hypothesis 2 was also partially supported (see Table 2). Worse objective QOL was significantly correlated with more severe negative symptoms and worse cognitive performance. However, the correlations between objective QOL and UPSA performance did not reach statistical significance, nor did the correlation between objective QOL and depressive symptom severity. We also found that demographic variables were associated with objective QOL; older and less educated participants reported lower involvement in daily activities and fewer interactions with friends and family members.

To examine the independent predictors of subjective and objective QOL, respectively, we conducted two multiple regression analyses (see Table 3). Extending analysis of the first hypothesis regarding subjective QOL, the independent variables entered were gender, diagnosis, depressive symptoms, and neuropsychological performance. In the context of these multiple factors, only depressive symptom severity and neuropsychological performance were independently associated with subjective QOL, with patients experiencing more severe depressive symptoms and better neuropsychological functioning also reporting worse subjective QOL (see Figure 1). Because the schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder participants differed significantly in their HAM-D scores, we examined the correlations between HAM-D score and subjective QOL in the two groups. There was no significant difference between the correlations (.56 and .50, respectively; z=.36, p=.719), suggesting that the relationship between depressive symptom severity and subjective QOL is similar in the two diagnostic groups.

Table 3.

Multiple regression analyses of variables predicting subjective and objective QOL

| Subjective QOLa | Objective QOLb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | p | β | p |

| Age, years | -- | -- | −.165 | .082 |

| Education, years | -- | -- | .194 | .058 |

| Gender (0 = female, 1 = male) | .018 | .847 | -- | -- |

| Diagnosis (0 = schizophrenia, 1 = schizoaffective disorder) | .015 | .880 | -- | -- |

| PANSS negative symptom severity | -- | -- | −.443 | <.001 |

| HAM-D depressive symptom severity | −.558 | <.001 | -- | -- |

| Neuropsychological Z-score | −.270 | .004 | .012 | .910 |

R2 = .361, F = 11.18, df = 4,83, p < .001.

R2 = .308, F = 8.89, df = 4,84, p < .001.

The multiple regression analysis relevant to the second hypothesis, regarding predictors of objective QOL, included age, education level, negative symptoms, and neuropsychological performance as predictors. Only worse severity of negative symptoms was independently associated with worse objective QOL (see Figure 1).

4. Discussion

The main finding of this study is that psychiatric symptoms are the best independent predictors of subjective and objective QOL in schizophrenia. The single best predictor of subjective QOL was the severity of depressive symptoms, whereas the single best predictor of objective QOL was the severity of negative symptoms. It appears that depressive symptoms and better cognitive functioning are associated with worse life satisfaction, whereas negative symptoms limit participation in daily activities and involvement with family and friends.

We expected that subjective and objective QOL would be related to each other, and that the predictors of subjective and objective QOL would be similar. However, we found that the correlation between subjective and objective QOL was low, and their relationships with patient characteristics varied, suggesting that these are separable constructs that should be assessed independently. These results add to the literature on outcome assessment in schizophrenia and suggest that the predictors of QOL (mainly negative and depressive symptoms) are different from the predictors of everyday functioning and community integration (i.e., cognition and psychiatric symptoms; Green et al., 1996; 2000; Twamley et al., 2002). The current results also echo previous findings from our research group regarding the relationship between QOL and depressive and negative symptoms using a health-related quality of well-being measure that combines subjective and objective QOL items (Kasckow et al., 2001; Mittal et al., 2006; Patterson et al., 1997).

Contrary to our expectation, cognitive performance and functional capacity, as measured by the UPSA, did not correlate with objective QOL (activity and social participation) in this sample. Although this lack of association is probably partly due to the differences in domains assessed, it is also probably due to the nature of each measure (i.e., cognitive tests and UPSA being performance-based vs. QOLI being a self-report measure). The relationship between these measures may be attenuated because an individual’s self-report may be affected by cognitive impairment or psychiatric symptoms, limiting its relationship to objective capacity. Additionally, performance on cognitive or functional skills tests may not translate into real-world behaviors due to interference from psychiatric symptoms, from lack of opportunity (e.g., the person can pay a bill by check on the UPSA, but does not pay bills or have a checkbook in the real world because someone else handles the person’s finances), or from environmental distractions, cues, or supports. We believe that negative symptoms have a greater effect on real-world functioning than they do on functional capacity in the laboratory.

Unexpectedly, we found that better cognitive performance was associated with worse subjective QOL in our sample, which may reflect a tendency in those with more intact cognitive abilities to have better insight regarding their psychiatric illness. It is possible that patients with severe mental illness internalize negative messages, leading to devaluation, feelings of depression, and lower QOL. It is also possible that those with better insight may appreciate the impact of their mental illness on their QOL, leading to symptoms of depression. Previous research also indicates that the relationship between cognitive functioning and QOL may not be straightforward: Hofer et al. (2005a) found no association, but Brekke and colleagues (2001) found that executive functioning moderated the relationship between psychosocial functioning and subjective QOL, such that patients with executive dysfunction showed a positive relationship between functioning and QOL, whereas intact patients showed a negative relationship between functioning and QOL. Furthermore, Bowie et al. (in press) have found that schizophrenia patients with better cognitive abilities had more severe depressive symptoms and also overestimated their level of disability. This study raises questions about the inter-relationships of these variables in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. However, to truly understand the interrelationships of these variables, longitudinal analyses would be required.

The current study had several limitations. Participants were all clinically stable, non-substance-abusing outpatients; thus, our results may not generalize to inpatient or substance-abusing samples. We used laboratory-based, performance-based measures of cognitive functioning and functional capacity, which cannot measure perfectly what a person can do or does do in the real world. Future studies would benefit from the use of collateral reports and real-life observations of functional capacity. The QOLI also has its limitations, in that the objective QOL items measure only participation in activities and relationships, and do not reflect the quality or success of the activities or social/family contacts. We did not include a measure of social skills performance, which may be important in social activity participation, or insight, which may affect the relationship between cognition and subjective QOL. We also did not include employment, marital status, or living independence in our models, because of small numbers of employed (n=5), married (n=9), or supervised-residence (n=11) participants in our study. Finally, our study was cross-sectional in nature, which precludes any conclusions regarding causality in the relationships between the variables. Bi-directional relationships are certainly possible (e.g., negative symptoms and limited activity participation may influence each other in a bi-directional manner, as may depression and subjective QOL). Bow-Thomas and colleagues (1999), for example, showed that lower levels of negative and depressive symptoms significantly predicted higher subjective QOL over time.

Treatment of schizophrenia continues to emphasize psychopharmacological management of positive symptoms (Ginsberg et al., 2005; Lehman and Steinwachs, 1998). Our findings suggest that positive symptom severity does not predict life satisfaction (subjective QOL) or activity participation (objective QOL). Negative symptoms and depressive symptoms, however, play a clear role in QOL, and should be considered important targets of schizophrenia treatment. Future intervention studies should incorporate QOL as an outcome measure to assess the effects of treatment on QOL. Mounting evidence suggests that psychosocial treatments (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, supported employment, social skills training, assertive community treatment, and cognitive training) are a necessary adjunct to antipsychotic medications (Granholm et al., 2005; Lehman et al., 2004; Twamley et al., 2003a; Twamley et al., 2003b). With aggressive use of adjunctive treatments to target depression and negative symptoms, QOL in schizophrenia may be improved.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dilip Jeste for reviewing the manuscript and Cynthia Zurhellen for her assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Becchi A, Rucci P, Placentino A, Neri G, de Girolamo G. Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia – comparison of self-report and proxy assessments. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(5):397–401. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RH. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; Florida: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RH, Schretlen DS, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised: Normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. The Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;12(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher KS. Multilingual aphasia examination. Iowa City, IA: AJA Associated; 1989. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Twamley EW, Anderson H, Halpern B, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Self-assessment of functional status in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.003. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bow-Thomas CC, Velligan DI, Miller AL, Olsen J. Predicting quality of life from symptomatology in schizophrenia at exacerbation and stabilization. Psychiatry Res. 1999;86(2):131–142. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Kohrt B, Green MF. Neuropsychological functioning as a moderator of the relationship between psychosocial functioning and the subjective experience of self and life in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(4):697–708. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Lenzenweger MF, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. The continuous performance test, identical pairs version: II. Contrasting attentional profiles in schizophrenic and depressed patients. Psychiatry Res. 1989;29(1):65–85. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Buican B. The construct validity of subjective quality of life for the severely mentally ill. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183(5):281–285. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199505000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JD, Heaton RK, Paulsen JS, Palmer BW, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. The relationship of neuropsychological abilities to specific domains of functional capacity in older schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(5):422–430. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg DL, Schooler NR, Buckley PF, Harvey PD, Weiden PJ. Optimizing treatment of schizophrenia. Enhancing affective/cognitive and depressive functioning. CNS Spectr. 2005;10(2):1–13. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900019337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden C. Stroop color and word test manual. Chicago, IL: Stoelting Co; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, Auslander LA, Perivoliotis D, Pedrelli P, Patterson T, Jeste DV. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for middle-aged and older outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):520–529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(3):321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr. Bull. 2000;26(1):119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Nuechterlein KH. Should schizophrenia be treated as a neurocognitive disorder? Schizophr. Bull. 1999;25(2):309–319. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sliwinski M. Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1991;13(6):933–949. doi: 10.1080/01688639108405109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6(4):278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Velligan DI, Bellack AS. Performance-Based Measures of Functional Skills: Usefulness in Clinical Treatment Studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm040. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, Harris J, Jeste DV. Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics. Relationship to age, chronicity, and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(6):469–476. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950060033003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12(3):426–445. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer A, Baumgartner S, Bodner T, Edlinger M, Hummer M, Kemmler G, Rettenbacher MA, Fleischhacker WW. Patient outcomes in schizophrenia II: the impact of cognition. Eur Psychiatry. 2005a;20(5–6):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer A, Baumgartner S, Edlinger M, Hummer M, Kemmler G, Rettenbacher MA, Schweigkofler H, Schwitzer J, Fleischhacker WW. Patient outcomes in schizophrenia I: correlates with sociodemographic variables, psychopathology, and side effects. Eur Psychiatry. 2005b;20(5–6):386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Wyatt RJ. Understanding and treating tardive dyskinesia. Guilford Press; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Zisook S, Palmer BW, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Jeste DV. Association of depressive symptoms with worse functioning in schizophrenia: a study in older outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(10):797–803. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasckow JW, Twamley E, Mulchahey JJ, Carroll B, Sabai M, Strakowski SM, Patterson T, Jeste DV. Health-related quality of well-being in chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia: comparison with matched outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2001;103(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karow A, Pajonc FG. Insight and quality of life in schizophrenia: recent findings and treatment implications. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(6):637–641. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000245754.21621.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test-64 Card Version (WCST-64) Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; Florida: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M, Naber D. Current issues in schizophrenia: overview of patient acceptability, functioning capacity and quality of life. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(Supl 2):5–17. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF. The effects of psychiatric symptoms on quality of life assessments among the chronic mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1983a;6(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF. The well-being of chronic mental patients: assessing their quality of life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983b;40(4):369–373. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790040023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plan. 1988;11(1):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, Dixon LB, Goldberg R, Green-Paden LD, Tenhula WN, Boerescu D, Tek C, Sandson N, Steinwachs DM. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):193–217. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Possidente S, Hawker F. The quality of life of chronic patients in a state hospital and in community residences. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1986;37(9):901–907. doi: 10.1176/ps.37.9.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Postrado LT, Rachuba LT. Convergent validation of quality of life assessments for persons with severe mental illnesses. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(5):327–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00449427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(1):11–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal D, Davis CE, Depp C, Pyne JM, Golshan S, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Correlates of health-related quality of well-being in older patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(5):335–340. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000217881.94887.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RMG, Malla AK, McLean T, Voruganti LPN, Cortese L, McIntosh E, Cheng S, Rickwood A. The relationship of symptoms and level of functioning in schizophrenia to general wellbeing and the Quality of Life Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102(4):303–309. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Neale JM. Schizophrenic performance when distracters are present: attentional deficit or differential task difficulty? J Abnorm Psychol. 1975;84(3):205–209. doi: 10.1037/h0076721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BW, Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Evans JD, Patterson TL, Golshan S, Jeste DV. Heterogeneity in functional status among older outpatients with schizophrenia: employment history, living situation, and driving. Schizophr Res. 2002;55(3):205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: Development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(2):235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Shaw W, Semple SJ, Moscona S, Harris MJ, Kaplan RM, Grant I, Jeste DV. Health-related quality of life in older patients with schizophrenia and other psychoses: Relationships among psychosocial and psychiatric factors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(4):452–461. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199704)12:4<452::aid-gps500>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. 2. Neuropsychology Press; Arizona: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri M, Nosè M, Bonetto C, Cristofalo D, Lasalvia A, Salvi G, Stefani B, Malchiodi F, Tansella M. Changes and predictors of change in objective and subjective quality of life: multiwave follow-up study in community psychiatric practice. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187(2):121–130. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo J, Roy-Byrne P, Reeder D, Alexander M, Deyer-O’Connor ED, Dagadakis C, Ries R, Patrick D. Longitudinal assessment of quality of life in acute psychiatric inpatients: reliability and validity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185(3):166–175. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciolla A, Patterson TL, Wetherell JL, McAdams LA, Jeste DV. Functioning and well-being of middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia: measurement with the 36-item short-form (SF-36) health survey. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(6):629–637. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.11.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twamley EW, Doshi RR, Nayak GV, Palmer BW, Golshan S, Heaton RK, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Generalized cognitive impairments, ability to perform everyday tasks, and level of independence in community living situations of older patients with psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(12):2013–2020. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Lehman AF. Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003a;191(8):515–523. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000082213.42509.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Bellack AS. A review of cognitive training in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2003b;29(2):359–382. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voruganti L, Heslegrave A, Awad AG, Seeman MV. Quality of life measurement in schizophrenia: reconciling the quest for subjectivity with the question of reliability. Psychol Med. 1998;28(1):165–172. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition: Administration and scoring manual. The Psychological Corporation; Texas: 1997a. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Third Edition: Administration and scoring manual. The Psychological Corporation; Texas: 1997b. [Google Scholar]

- Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663–667. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]