Abstract

The field of clinical behavior analysis is growing rapidly and has the potential to affect and transform mainstream cognitive behavior therapy. To have such an impact, the field must provide a formulation of and intervention strategies for clinical depression, the “common cold” of outpatient populations. Two treatments for depression have emerged: acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and behavioral activation (BA). At times ACT and BA may suggest largely redundant intervention strategies. However, at other times the two treatments differ dramatically and may present opposing conceptualizations. This paper will compare and contrast these two important treatment approaches. Then, the relevant data will be presented and discussed. We will end with some thoughts on how and when ACT or BA should be employed clinically in the treatment of depression.

Keywords: clinical behavior analysis, depression, psychotherapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, behavioral activation

The field of clinical behavior analysis is growing rapidly. After beginnings documented in this journal (Dougher, 1993; Dougher & Hackbert, 1994) and elsewhere (Dougher, 2000), it has become an integral part of a “third wave” of behavior therapy (Hayes, 2004; O'Donohue, 1998) that has the potential not only to influence but also to transform mainstream cognitive behavior therapy in meaningful and permanent ways.

To have such an impact, the field must provide a formulation of and intervention strategies for clinical depression, the “common cold” of outpatient populations. The phenomenon of depression currently is parsed into several diagnostic categories by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The most common diagnosis, major depressive disorder, is applied when an individual reports a combination of feelings of sadness, loss of interest in activities, sleep and appetite changes, guilt and hopelessness, fatigue or restlessness, concentration problems, and suicidal ideation that persist for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks. Epidemiological data from a large representative U.S. sample indicate a lifetime prevalence rate for major depressive disorder of 16% (and an annual prevalence rate of 7%), which suggests that over 30 million Americans will struggle with diagnosable depression during their lifetimes (Kessler, McGonagle, Swartz, Blazer, & Nelson, 1993). The costs of depression are significant, not only for those who are suffering but also because of the high economic burden of depression, much of which is attributed to work-related absenteeism and lost productivity (Greenberg et al., 2003).

Clinical behavior analysts, historically skeptical of using the DSM as the basis for understanding problem behavior, are especially cautious to avoid reifying a descriptive label, such as major depressive disorder, into a thing and using it as an explanation for the symptoms it describes (Follette & Houts, 1996). Instead, of greater interest are the patterns of behavior that lead to the label of depression being applied and how best to characterize and alter these patterns to improve lives. Toward this end, several behavior-analytic descriptions of depression are now available (Dougher & Hackbert, 1994; Ferster, 1973; Kanter, Cautilli, Busch, & Baruch, 2005). These descriptions generally accept Skinner's (e.g., 1953) view that emotional states, such as depressed mood, are co-occurring behavioral responses (elicited unconditioned reflexes, conditioned reflexes, operant predispositions). To the extent that the various responses labeled depression appear to be integrated, it is because the behaviors are potentiated by common environmental events, occasioned by common discriminanda, or controlled by common consequences. These behavioral interpretations also recognize that depression is characterized by great variability in time course, symptom severity, and correlated conditions.

This paper will focus on two behavior-analytic treatments for depression that have emerged: acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999) and behavioral activation (BA). A third behavior-analytic approach, functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP; Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991) has been used to improve cognitive therapy for depression (Kanter, Schildcrout, & Kohlenberg, 2005; Kohlenberg, Kanter, Bolling, Parker, & Tsai, 2002). FAP is based on a broad functional analysis of the therapeutic relationship (e.g., Follette, Naugle, & Callaghan, 1996) rather than a specific behavioral model of depression; thus it will not be described here. Two current variants of BA exist, BA (Martell, Addis, & Jacobson, 2001) and brief behavioral activation treatment for depression (BATD; Lejeuz, Hopko, & Hopko, 2001). This paper will focus on BA rather than BATD, because BA and BATD have recently been compared and contrasted (Hopko, Lejuez, Ruggiero, & Eifert, 2003). As we will show, at times ACT and BA, at the level of function if not technique, may suggest largely redundant intervention strategies. However, at other times the two treatments differ dramatically and may in fact present opposing conceptualizations. How, then, is a clinical behavior analyst to choose between ACT and BA? The body of this paper will compare and contrast these two important treatment approaches. Then, the relevant data on ACT and BA for depression will be presented and discussed. We will end with some thoughts on how and when ACT or BA should be employed clinically in the treatment of depression.

Throughout this article we refer to the ACT (Hayes et al., 1999) and BA (Martell et al., 2001) manuals, although two caveats are required about our focus on manuals. First, both treatments explicitly eschew the cookbook, session-by-session approach that accurately describes some cognitive behavior therapy treatment manuals. Both BA and ACT are principle based, explicitly encouraging the use of any intervention techniques consistent with their underlying principles, whether or not the technique is described in the manual. Thus, there is some danger in comparing the two treatment manuals. We believe we have been sensitive to this danger and have tried to avoid idiosyncratic interpretations of specific techniques without reference to underlying principles. That said, at times we make use of specific acronyms and techniques presented in the manuals for clinical use, as shorthand encapsulations of key principles.

Second, this paper is organized in terms of key differences between the two manuals. Although we describe the purported functional impact of these treatment techniques on client behavior, the paper is not organized in terms of these functional processes. In fact, established functional relations between specific treatment techniques and client behaviors for both BA and ACT largely await experimental investigation, although much work is underway in this regard, particularly for ACT. We encourage future researchers and authors to pursue this work and develop these analyses.

Depression and Avoidance

Both ACT and BA conceptualize depression largely in terms of contextually controlled avoidance repertoires. In BA, the relevant history and context involve direct contingencies that have shaped and maintained avoidance behavior through negative reinforcement. The ACT model, however, focuses on a verbal context that dominates over and creates insensitivity to direct contingencies. We will first discuss ACT's more complex model and then turn to BA as a contrast. We note that this focus on avoidance is largely a departure from traditional behavioral models of depression that emphasized reductions in positive control rather than increases in aversive control (Lewinsohn, 1974), although Ferster (1973) did emphasize the role of avoidance in his seminal functional analysis of depression. Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, and Strosahl (1996) have provided a convincing review showing that avoidance may underlie a host of psychological problems, including depression, and the specific relation between avoidance and depression has received empirical support as well (reviewed by Ottenbreit & Dobson, 2004).

Act

ACT maintains that the fundamental problem in depression is experiential avoidance: an unwillingness to remain in contact with particular private experiences coupled with attempts to escape or avoid these experiences (Hayes & Gifford, 1997; Hayes et al., 1996). Experiential avoidance is not an account of depression per se; rather, it is posited as a functional diagnostic category (Hayes & Follette, 1992) that identifies a psychological process key to many topographically defined diagnostic categories, including depressive disorders. As pointed out by Zettle (2005a), although the term experiential avoidance accommodates both escape and avoidance behavior, experiential escape may be more appropriate for depression in that the depressed individual may more likely be preoccupied with terminating psychological events that have already been experienced and are currently being endured, such as guilt, shame, and painful memories of loss experiences, rather than those that are anticipated and avoided. We will use the more general term experiential avoidance because it is more consistent with ACT usage.

The problem, according to ACT, is not so much the initial experience of aversive private events—in ACT terminology, clean discomfort (e.g., sadness about not seeing one's children daily after separation from a spouse)—but that one rigidly follows rules for living that dictate experiential avoidance as the necessary response to such aversive private events. Thus ACT emphasizes that experiential avoidance itself is fueled by a verbal (i.e., rule-governed) process. Such rules may take many forms, such as “I can't stand to feel this way,” “Having feelings makes one weak and vulnerable,” or “I need to be happy.” These rules, in the context of particular aversive private events, may result in avoidance behavior that also takes many forms, such as avoiding seeing one's children so as to not feel sad and have thoughts of being a failure as a parent, oversleeping to escape daytime stress (or undersleeping, if dreams or thoughts while in bed are aversive), overeating to combat loneliness in the evening (or undereating, if eating results in thoughts about being fat, about not having someone to eat with, etc.), rumination to avoid the anxiety that accompanies active problem solving, avoidance of challenging social situations where one might fail (or going to the party but passively sitting on the couch all night), or drinking alcohol excessively to block the pain of grief.

ACT postulates a significant role for indirect, derived verbal processes in promoting experiential avoidance.1 For instance, many aversive private events may be elicited indirectly. Consider a client for whom the word loss is in an equivalence relation with actual painful interpersonal losses (e.g., death of a parent or experience with relationships ending badly due to partner infidelity). The physical absence of a current significant other on a Saturday evening (for legitimate reasons, such as a business trip) might evoke a verbal response, as in “He's gone,” that is in an equivalence relation with loss. When this occurs some of the aversive functions of actual losses may now be present (RFT refers to this as a derived transformation of stimulus functions), despite the fact that this relationship has not been lost and is not in jeopardy. These aversive private events may now occasion escape behavior, such as frantic calls to the significant other, binge eating, or alcohol use, that may contribute to the demise of the relationship. ACT posits that this sort of verbal control over behavior dominates nonverbal environmental control, perhaps due, in this case, to historical operations that have established losses as particularly aversive (Dougher & Hackbert, 2000).

According to ACT, despite the fact that such avoidance tends to maintain and exacerbate rather than solve problems in the long run, experiential avoidance repertoires are maintained because they are verbally controlled (rule governed), are successful in the short run, and block contact with or create insensitivity to other contingencies (Hayes & Ju, 1998). For example, a client reports staying in bed all day because she “felt depressed,” lamenting how things might be different tomorrow if she feels less depressed. Staying in bed requires lower response effort than getting up, getting ready for work, and going to work. Thus, a direct escape contingency is involved, but so too is the verbal rule specifying the need to feel better before acting differently. Of course, the decision to stay in bed until she feels less depressed also prevents contact with other contingencies that might lead to less depression.

BA

BA's model of depression emphasizes nonverbal processes and appears to be more parsimonious. The traditional BA treatment model viewed the overt behavioral reductions in depression as a result of loss of or reductions in response-contingent positive reinforcement and viewed the affective components of depression as respondent sequelae of such losses or reductions (Dougher & Hackbert, 1994; Ferster, 1973; Kanter, Cautelli, Busch, & Baruch, 2005; Lewinsohn, 1974). Current BA, largely based on Ferster (1973), postulates a greater role for escape and avoidance from aversive internal and external stimuli. Ferster further suggested that the escape–avoidance repertoire is largely passive, which also leads to a decrease in positive reinforcement relative to what an active repertoire would provide.

Although the topographies of the avoidance repertoires targeted by ACT and BA are basically the same (e.g., oversleeping, overeating, rumination, alcohol consumption, and many others), the controlling variables and relevant history postulated are somewhat different. BA contends that aversive private events occur in response to the presentation of punishers or loss of reinforcers. The BA model recognizes that depressed individuals often tact these aversive private experiences (i.e., emit vocal responses that are putatively controlled by internal stimulation), but unlike ACT, no indirect, derived (verbal) processes through which private events become aversive are specified. Aversive private events are thought to be elicited by contingencies that involve loss or deprivation.

Likewise, BA posits no rule-governed process. Avoidance of aversive private events is evoked by the events themselves or by their environmental determinants or correlates. BA assumes that direct contact with contingencies of negative reinforcement can initially establish and later maintain avoidance repertoires.2 Verbal responses are recognized, but these are often conceptualized as part of the avoidance repertoire (e.g., mands for succor or relief). In comparison, ACT emphasizes how faulty rules about the need to change or control private events promote experiential avoidance and decrease contact with external environmental events.

Like ACT, BA holds that avoidance, even when it works in the short term, produces additional long-term problems, because more flexible repertoires of problem solving and repertoires based on stable positive reinforcement are either extinguished, depotentiated, or never developed. Both ACT and BA suggest the clinically relevant problem is not the initial (albeit aversive) private event, but that one responds to the event with avoidance. BA labels these avoidance patterns secondary coping behaviors because they are a response to the initial aversive stimuli but paradoxically maintain or exacerbate the depressive episode. Developing more proactive alternative coping behaviors to replace these patterns is the primary focus of BA.

Functional Assessment of Avoidance in BA and Act

Any behavior-analytic treatment should start with functional assessment. Classical functional analysis, as in experimental demonstrations of behavioral control, is generally considered impossible in outpatient settings. Nevertheless, clinical behavior analysts perform quasifunctional analyses of client behaviors. Given the somewhat differing conceptualizations of avoidance by BA and ACT, how does this translate into different assessment strategies? BA provides a structure for detailed assessment of contingencies that maintain the depressive behavior, focusing mostly, as described above, on the role of negative reinforcement in maintaining avoidance. (We note here that BATD adds an emphasis on positive reinforcement for depressive behavior.) In practice, functional assessment explicitly focuses on identifying and increasing awareness of and the difficulties resulting from avoidance patterns and events that precede them. In ACT, the first step is to establish creative hopelessness, in which there is an explicit focus on increasing awareness of the futility of, and the faulty verbal rules that support, experiential avoidance. These therapeutic procedures are not as dissimilar as they might first appear.

In BA, therapists are taught to engage in a simple functional assessment, focusing on contingency-shaped avoidance behavior. This key technique in BA clearly renders it an advance over earlier BA strategies that targeted pleasant events and did not involve an idiographic assessment of function (Kanter, Callaghan, Landes, Busch, & Brown, 2004). In fact, after over 30 years of cognitive behavioral depression treatment development, behavior analysts may finally rejoice to read the following quote from the BA manual:

Behavior matters. This is the primary motto of BA, and it is important that the therapist accept this concept wholeheartedly if they are to conduct competent BA. …The therapist, regardless of the technique being used for a specific intervention, should be asking him- or herself, “What are the conditions occasioning this behavior (the context) and what are the consequences of this behavior for the client (the function)?” (p. 106)

BA therapists teach their clients to perform a quasifunctional analysis of their own out-of-session behavior. Clients specifically are taught to use the acronym TRAP: Assess the situational Trigger, identify one's own aversive private Response to the situation (i.e., anxiety), and finally recognize the Avoidance Pattern that follows. For example, a TRAP of a client seen by the first author was as follows: trigger = meeting someone at a social event for whom the client had strong feelings; response = feeling anxious and overwhelmed; avoidance pattern = not talking about how she really feels, keeping the conversation superficial, and finding a way to escape the conversation as soon as possible.

In addition to increasing awareness of avoidance patterns, assessment in BA also seeks to highlight the futility of avoidance as a long-term solution to problems. In this way, BA assessment bears some resemblance to ACT's creative hopelessness, which we describe next. For example, the BA authors describe the assessment of a young man who had been repeatedly driving past his lover's house to confirm that she is at home and not out with other men. The authors state,

We then have a hint at the real goal, to avoid anxiety. If this is described to the young man, and he agrees, we have reached an important first step. … Having learned that his goal is to be free of the anxiety about his lover seeing other men, we would then ask: How long does this freedom from anxiety last? If this is truly a solution, why must you do the same thing over and over again? (pp. 131–132)

Repeatedly throughout treatment, BA therapists are encouraged to engage in such questioning, to help their clients recognize the limited utility, in terms of anything but short-term negative reinforcement, of avoidance patterns. The main difference with ACT is that the BA therapist has no unique conceptualization for the role of rules or derived transformation of stimulus functions that maintain the problem; thus, the assessment takes the form of traditional verbal dialogue about functional relations among discriminative stimuli, avoidance behaviors, and their consequences.

Treatment in ACT, when conducted in its traditional order, begins with creative hopelessness. The goal of this stage is to “draw out the system” in which the client is trapped; namely, identifying how experiential avoidance appears specifically relevant to his or her struggles. The “hopelessness” achieved in creative hopelessness is experiential contact with the futility of experiential avoidance, a growing suspicion that one's own verbal rules may be part of the problem rather than the solution, a confusion about what to do next, but a sense that it will be different and counterintuitive. Through mostly Socratic-style questioning (e.g., “What do you want?”; “What have you tried?”; and “How has that worked?”), the client is guided toward a recognition of the unworkability of experiential avoidance.

Consider a client seen by the third author who presented during his fifth major depressive episode for treatment to decrease depression and anxiety, increase self-esteem, improve his relationship with his wife, and advance in his career. The initial assessment revealed that he had tried numerous treatment approaches including antidepressants, inpatient hospitalization, individual therapy, and couples therapy. He reported using various personal strategies, such as deep breathing and, alternatively, encouraging and berating himself (trying to tell himself to “just let things go,” or “block things out,” or reminding himself of his positive qualities). Despite these efforts, he presented for treatment disgusted with himself for being an incompetent, unlovable failure. This client identified several verbal self-rules that appeared to promote experiential avoidance as a method for solving life's problems, including, “If you express needs then you'll be seen as an overemotional baby,” “emotions can easily become overwhelming,” and “if I was perfect (or at least more self-assured) everything in my relationships would be okay.” Yet, despite this client's inhibition of emotional expressivity, attempts to blunt and block emotions, and moves to verbally bolster his self-worth, things had not gotten better. From an ACT perspective, reviewing the client's treatment history is an essential aspect of the assessment, because it helps the client to make contact with the fact that his logical and reasonable attempts to remove depression have not worked. The next move is to contact the possibility that maybe such attempts cannot work. This is the essence of creative hopelessness.

Most ACT descriptions of how therapists should conduct creative hopelessness suggest highlighting the contradiction between verbal rules that promote experiential avoidance and the long-term unworkability of the accompanying behavior, rather than simply viewing the interaction as a functional assessment. For example, note the following therapist response to a chronic worrier, who is first recognizing this discrepancy:

But maybe we are coming to a point in which the question will be, “Which will you go with? Your mind or your experience?” Up to now the answer has been “your mind,” but I want you just to notice also what your experience tells you about how well that has worked. (Hayes et al., 1999, p. 97)

Thus, the goal in this phase is for the client to experience the functional consequences of avoidance behavior, which is the same goal as functional assessment in BA. However, because the ACT notion of experiential avoidance emphasizes the role of verbal rules and derived transformation of aversive private stimulus functions in preventing contact with external environmental events, this phase does not look like traditional assessment as in BA. Instead, the ACT therapist takes caution not to simply supply additional verbal rules to describe the client's experience; rather, the client obtains the awareness, to the extent possible, experientially. For an ACT therapist, extended verbal dialogue, although necessary, risks inadvertently reinforcing the notion that verbal solutions to psychological problems may be found. As such, these verbal dialogues are buttressed with or centered around metaphors or experiential exercises that point to a different “agenda.” For instance, the therapist might note that the client's situation appears kind of like falling into quicksand; the natural, sensible thing to do seems to be to struggle to get out, but that does not work in quicksand; it only makes matters worse.

Thus, it may be the case that ACT identifies BA's TRAPs over the course of treatment, but explicit assessment in ACT, as presented to the client, focuses on the verbal context in which experiential avoidance occurs. ACT clients are asked to monitor FEAR: Fusion with your thoughts, Evaluations of your experience, Avoidance of your experiences, and Reason given for your behavior. Note the parallel placement of avoidance in the TRAP and FEAR acronyms and how the surrounding letters shift the focus of assessment from nonverbal to verbal variables.

Therapeutic Goals

One might suggest that therapeutic goals not only distinguish ACT from BA but also distinguish ACT from most, if not all, of the mainstream medical and psychological community, including other “third wave” approaches. Whereas the goal in BA, simply put, is to reduce the cluster of responses, both public and private, collectively labeled as depression, ACT views efforts to directly change private events with caution. The caution is based on a concern that these efforts might be co-opted into a generalized experiential avoidance response class. Accordingly, during creative hopelessness especially but throughout treatment, ACT therapists highlight the long-term problems associated with experiential avoidance, notably the narrowing of behavioral repertoires and decreased contact with direct experience.

If not directly reducing the aversive private events that in part define depression, what then is the goal in ACT? The goal of ACT is to increase contact with direct experience and create more flexible, value-directed repertoires that will persist in the presence of previously avoided private events, such as those labeled depression. As told to clients, the goal is to feel whatever is to be felt as one commits to and engages in value-directed behavior (Hayes et al., 1999, p. 77). By taking this stance against changing private events and for the importance of aversive emotions, ACT has positioned itself in opposition to mainstream psychiatry and psychopharmacology as well as cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, which has largely adopted the medical model with its underlying goals (e.g., reduction of aversive private symptoms) and assumptions (e.g., “the assumption of healthy normality”; Hayes et al., 1999, p. 4).

BA explicitly rejects the medical model of depression by viewing depression not as an illness but rather as a direct consequence of learning history (Jacobson & Gortner, 2000; Martell et al., 2001). Nevertheless, BA authors clearly distinguish the position of BA from that of ACT: “Unlike other therapies involving acceptance, however, BA considers the experiences of people who are depressed as experiences worth changing” (Martell et al., 2001, p. 64). However, in line with the traditional behavior-analytic position on private events as causal variables (Moore, 1980), BA argues that the best way to achieve such reductions in aversive private experience is through overt behavioral activation (working from the outside in) rather than through attempts at direct manipulation of private experience. Thus, BA clients are taught not to try to reduce private experiences directly. In addition, even though BA targets private experience through overt behavioral activation, BA by no means offers the client the possibility that aversive private experiences can be completely eliminated: “The goal should not be that the client be free of depression, as this cannot be guaranteed. Regardless of how a person feels they can engage in activities that have been important to them” (Martell et al., p. 96).

In this regard, BA endorses a position quite similar to that of ACT, because ACT acknowledges that some private events are changeable. Specifically, ACT therapists acknowledge openly to clients that the quality of private experience, when one is “fused with” and trying to control the experience (e.g., “dirty discomfort”), is worth changing and is changeable (Hayes et al., 1999, p. 136), but is not changeable if one is trying to change it. Thus, in this way, ACT and BA are quite similar. Both maintain that direct attempts to change the initial aversive private experience are potentially problematic, but one can change one's behavioral response to the initial experience, and this may reduce its aversive quality. ACT therapists, however, are extremely careful to avoid generating additional goals around reducing private experience and increasing rule governance. BA therapists, in contrast, have no qualms making the point.

In closing, this section focused on the conceptual stance taken toward symptom reduction and how this stance is communicated to the client. Not yet addressed is the separate issue of whether the therapies actually produce symptom reduction, which is addressed below.

Acceptance

Act

Acceptance and interrelated processes such as defusion, mindfulness, and willingness play a fundamental role in ACT, and a complete array of methods is provided in the ACT manual to engage these processes (see also Hayes & Wilson, 2003, for discussion of how these processes are interrelated with acceptance). Indeed, their prominence is implied by the position of acceptance in the treatment's title, and the importance of acceptance cannot be overstated. Acceptance techniques are used throughout treatment; building an acceptance repertoire is seen as an important precursor to value-guided action, which will undoubtedly necessitate the experiencing of distress along the way.

As stated colloquially in the ACT manual, acceptance is “an active process of feeling feelings as feelings, thinking thoughts as thoughts, remembering memories as memories, and so on” (p. 77). In practice, therapists are encouraged to use the term willingness rather than acceptance because acceptance may imply tolerance or resignation, which is not consistent with the ideal acceptance repertoire, characterized by an active, committed, and nonevaluative approach to previously avoided private events.

The targets and functions of ACT's related defusion, acceptance, and willingness methods vary (Hayes & Wilson, 2003). In general, the goal of acceptance is to increase nonevaluative contact with previously avoided here-and-now private events. Because, as stated earlier, ACT posits that aversive private events are often verbally derived experiences, many of the techniques involve altering derived stimulus functions to facilitate contact with direct experience. For example, the milk, milk, milk defusion technique, in which a negatively evaluated word or phrase is quickly repeated for several minutes, appears to partially extinguish the word's derived aversive functions, facilitating acceptance (Masuda, Hayes, Sackett, & Twohig, 2004). Such defusion exercises promote discriminations between verbal responses to events and the events themselves and establish these verbal responses as somewhat arbitrary; thus, an event's verbally derived functions that promote experiential avoidance may be extinguished and lead to increased acceptance of the initial event.

Other techniques, such as the Joe the Bum metaphor, in which the client is asked to imagine the effort required to keep Joe the Bum from a party rather than accepting his unwanted presence, may be seen as establishing operations that establish approach functions and depotentiate avoidance functions while minimizing rule governance. Still other exercises, such as the observer exercise, a lengthy guided imagery exercise during which the client is led to contact a variety of private events to experience a stable sense of self from which private events are experienced, may be seen, at least in part, as exposure exercises, designed to establish and maintain contact with a range of private experiences, although other interpretations certainly are possible. ACT and RFT theorists are beginning to explore interpretations of the functions of these techniques in RFT terminology (e.g., some interventions target contextual variables that control relational responding, whereas others target contextual cues that control the transformation of function given the occurrence of relational responding), but little has been published on this topic to date.

BA

Unlike ACT, in which acceptance of private experience precedes and facilitates value-guided action, BA moves directly to overt action and assumes that acceptance will follow. BA therapists teach clients that if they want to change their depression, they must accept how they feel and focus on changing their overt behavior. This, in turn, will lead to change in depression. Thus, as in ACT, the emphasis is on the eponymous term, in this case activation (discussed next) rather than acceptance, but acceptance is clearly promoted by the treatment. Although no specific acceptance strategies are specified (with one exception, mindfulness, described below), the ability to activate in the presence of aversive private events fundamentally entails the acceptance, at least temporarily, of those aversive events.

How acceptance functions in the two treatments is somewhat different, however, and the distinction between ACT and BA here is clear and cogent. In BA, as stated above, the overall goal is reducing depression, and the use of acceptance is strategic in achieving that goal. BA views depression as a natural result of difficult life events and “therefore, it doesn't make sense to try to fight it” (Martell at al., 2001, p. 93). According to BA, fighting depression by engaging in avoidance behavior paradoxically maintains and exacerbates the depression; thus, the focus is on countering avoidance behavior and building active problem-solving repertoires. As relevant to acceptance, clients are taught to activate themselves regardless of depressed moods: “Clients benefit when they can act while acknowledging that they didn't feel like acting at the moment” (p. 93).

In ACT, any attempt to use acceptance strategies in the service of reducing the primary aversive experience of depression functionally transforms the strategies into experiential avoidance and is to be avoided. For example, consider a BA client seen by the first author, who reported being unable to stop ruminating about problems she was having at work. The therapist suggested a mindfulness exercise to her, in which she goes for a walk and focuses on the physical sensations experienced. The therapist explained that it would potentially help her “to attend to the present moment” and, borrowing ACT parlance, “get some distance from the rumination machine.” She then asked if the exercise would also help her to relax and feel better. Because the therapist was conducting BA, he said that he hoped it would help her to feel better, because rumination makes her problems worse (functionally, rumination is avoidance) and this alternative might be enjoyable (by helping her to contact sources of positive reinforcement). If the therapist had been conducting ACT, he would not have responded with such a reassurance. Instead, he might have asked her if, by hoping the exercise would help her feel better, she was again engaging in an old emotional control agenda, or gently asked her if she would like to repeat the thought “this exercise will help me feel better” for several minutes to see what happens to its functions.

Activation

BA

In BA, activating clients is the focus of therapy, and the treatment uses the full arsenal of behavioral techniques to achieve behavioral activation, including scheduling behavioral activities, graded homework assignments, in-session rehearsal and role playing of targeted behaviors, therapist modeling of targeted behaviors, managing situational contingencies to make initiation and successful completion of targeted behavior more likely, problem solving to identify specific behavioral targets as solutions to specific problems, and training to overcome skills deficits that interfere with initiation and maintenance of targeted behaviors. As mentioned above, the key distinction between current BA and earlier forms of behavioral activation for depression (Hammen & Glass, 1975; Lewinsohn, 1974; Lewinsohn, Biglan, & Zeiss, 1976; Lewinsohn & Graf, 1973; Lewinsohn & Libet, 1972) is that activation is not focused on increasing pleasant activities per se, but is targeted toward specific areas of passivity and avoidance that have been identified idiographically. Once target behaviors are identified, attempts to block avoidance and activate these alternate behaviors are also monitored with an eye towards function. In addition to using the TRAP acronym to identify avoidance, clients are taught to “get out of TRAPs and get on TRAC” by replacing Avoidance Patterns with Alternate Coping behaviors.

In addition, clients are taught to use the acronym ACTION to monitor ongoing avoidance patterns and implement changes: Assess how this behavior serves you, Choose either to avoid or activate, Try out whatever behavior has been chosen, Integrate any new behaviors into a routine, Observe the outcome, and Never give up. Note how this acronym encourages clients to adopt a functional–experimental approach to evaluating their behavior—to develop hypotheses about the function of various behaviors, take action, and observe the consequences. Taking such an approach might lead clients to become better able to describe the antecedent and consequential stimuli that control their behavior (i.e., increased self-awareness) and lead to the development of accurate verbal rules (i.e., tracks), which might facilitate maintenance of treatment gains. Finally, by ending with “Never give up,” BA attempts to encourage the persistence of behavior in the face of obstacles. Pursuit of goal-directed activity in the face of obstacles is also emphasized in ACT's values work, a topic we discuss next.

Act

ACT includes behavioral activation as well, but focuses instead on values and commitment, again emphasizing verbal over nonverbal processes. According to ACT, in addition to a functioning acceptance repertoire, a set of clearly defined values and associated goals are essential prerequisites for guiding activation. Values, defined in ACT as “verbally construed global desired life consequences” (Hayes et al., 1999, p. 206), may be seen as self-rules (specifically augmentals) that strategically take advantage of the insensitivity to contingencies generated by rule-governed behavior. By helping clients to identify, create, and clarify values, and then to make a verbal commitment to activation in the service of those values, the ACT therapist, after having spent much of treatment dismantling and distancing from verbal rules that promote emotional control and derived transformation of stimulus functions that support experiential avoidance, now utilizes these processes in an attempt to generate high-strength response classes that will persist in the face of avoidance contingencies. The difference is that the focal response classes consist of overt approach behaviors, rather than responses that temporarily terminate or preempt private events. Indeed, engaging in these value-directed approach behaviors often elicits and evokes the very private events that were previously avoided—hence, the initial focus on developing a functioning acceptance repertoire prior to making a commitment to behave toward personal values.

Thus, values take priority over activation per se in ACT. Like acceptance in BA, activation in ACT is implied and stated as important, but no activation strategies are specified. Instead, the manual (Hayes et al., 1999) states that, as treatment culminates,

ACT takes on the character of traditional behavior therapy, and virtually any behavior change technique is acceptable. The difference is that behavior change goals, guided exposure, social skills training, modeling, role playing, couples work, and so on, are integrated with an ACT perspective. Behavior change is a kind of willingness exercise, linked to chosen values. The integration of traditional behavior therapy and ACT in this phase is an important topic, but is well beyond the scope of this book. (p. 258)

As an illustration, consider again the male client with a history of multiple depressive episodes described earlier. One value of his was to be a good husband, with one specific goal being to improve his communication with his wife. Pursuit of this goal necessitated articulating his needs and feelings to his wife and apologizing for and making a commitment to discontinue certain relationship-weakening behaviors (e.g., he had previously belittled his wife as a way of terminating feelings of vulnerability when his wife tried to talk to him about their relationship). Engaging in these value-directed responses required that he persist in the face of feelings of self-doubt and vulnerability and thoughts that he was an “overemotional baby” who was unlovable. Not surprisingly, when he did this his wife reported experiencing him as more open, available, and not so closed off, and both reported increased closeness, understanding, and positive contact in the relationship.

In some ways ACT and BA are similar in that both view simple scheduling of pleasant events as meaningless if it is attempted independent of a larger assessment that delineates idiographic areas of activation. BA addresses this limitation and even discusses goals somewhat, but does not match ACT's technical or theoretical sophistication with respect to values, their behavioral operationalizations, and their role in therapy. On a case-by-case basis, however, behavioral activation in BA and value-guided action in ACT may look identical, especially for clients who may already have clear and well-defined values and may not need the additional values work conducted in ACT.

Consider the example immediately above and how the intervention could have been conducted from the TRAP/TRAC and ACTION framework with the value only implied: The trigger (T) could have been a previous discussion initiated by his wife about their relationship; the responses (R) would have been his feelings of vulnerability, self-doubt, and negative self-thoughts; the avoidance patterns (AP) would have been that he belittled his wife and shut down as a way of escaping the feelings; and the alternative coping (AC) would have been that instead he initiates the discussion himself, articulates his needs and feelings during the discussion, and apologizes for his past behavior. According to ACTION, he would have assessed (A) that his belittling her and shutting down was making his marriage worse, chosen (C) instead to activate, tried out (T) the new behaviors of discussing feelings and apologizing, committed to engaging in these behaviors regularly, thereby integrating (I) them into a routine, observed (O) that his wife responded positively to the new behaviors, and reminded himself to never give up (N) if and when she does not respond positively.

An acronym comparison again summarizes the similarities and differences. Whereas BA encourages ACTION, ACT more simply encourages clients to ACT: Accept your reactions and be present, Choose a valued direction, and Take action. Note that both emphasize choice (but ACT expands considerably on what is to be chosen, i.e., values), and both encourage behavior change in the form of action. BA's acronym additionally encourages functional assessment, now in the context of activation (the A and O), whereas ACT's ACT does not encourage functional assessment but simply focuses on acceptance in addition to choosing values and taking action.

Case Examples

To illustrate the similarities and differences between ACT and BA, we present two case examples, adapted from existing writings on ACT and BA.

Act

The following ACT case was adapted from Dougher and Hackbert (1994, pp. 330–333). The client was a 23-year-old depressed female college student, and the treatment goal was “to help the client achieve acceptance of her private events while pursuing those activities and goals she identified as being important.” In this session (Session 8), the client is talking about her reaction to a fight with her nonexclusive boyfriend:

C: We had a fight, and he left, I felt so angry, so bad. I just couldn't, didn't want to go through with it. I started to get really down. I just wanted to get drunk. … I started to drink, but I'm not much of a drinker, and when I did, it seemed like just drinking made me think about it more.

T: Like trying not to think of pink elephants makes you think of pink elephants more. That's true of everything you do to stop thinking of something or trying not to have a feeling. It just makes it worse.

C: So, what do you do?

T: Don't try not to have feelings. Have them.

C: Does that work? Will the feelings go away?

T: No, but at least you're not doing anything to make them worse.

C: Well, how do you get rid of the feelings?

T: You don't. You can't.

C: What do you do about them?

T: Have them. You want to do something you can't do. You want not to have thoughts and feelings. But that can't happen, you know. You're alive and they're part of you.

In this transcript, the ACT therapist clearly goes after the consequences of experiential avoidance (“it just makes things worse”) and introduces acceptance as an alternative. An ACT therapist might also introduce a metaphor here to try to move beyond a literal discussion. Notice also that the therapist did not just go after the link between private events and escape or avoidance, which a BA therapist might also do, but also highlighted the verbal rules that support experiential avoidance—that feelings should be terminated. There is little focus on the trigger (the argument) or, at this point, on alternative coping behaviors. As values work has yet to occur at this stage of ACT, alternative behaviors, other than acceptance, have yet to be delineated. A BA therapist might downplay acceptance here, instead introducing TRAP and TRAC as a way to assess the specific situation and develop alternative coping strategies that subsume acceptance.

In the following transcript, which occurs later in therapy (Session 17), the work has focused on value-guided activation, and it becomes more difficult to distinguish between ACT and BA. In this segment, the client is talking about a date with a guy she met in one of her classes.

C: [Before the date] I was really, uh, starting to get nervous and, uh, thinking that, uh, that it was a mistake to have agreed to go out with him. I don't know why I was, you know, so nervous. I have no confidence. Anyway, I started thinking about accepting the feelings and the stuff we talked about, you know, and just got ready.

T: So you went out?

C: Yeah, and it was pretty good. But the whole time, I'm like telling myself he hates me, why am I doing this? What's the point? You know. But it was good.

Note that the client describes the problem in terms of anxiety and a litany of depressotypic thoughts, defusion from which seems to be part of a functioning acceptance repertoire that she has acquired over the course of therapy. This appears to depotentiate the escape response and allows her to go on and enjoy the date. A BA client would be more likely to describe the problem in terms of avoidance and rumination, and the need to stay active in the presence of such feeling and thinking patterns. But the key outcome—engagement in value-directed behavior (activation)—is the same.

At the end of therapy, the client had terminated the nonexclusive relationship and was considering taking a job in Washington D.C., a move consistent with her educational training and values. In addition, “the client's depression clearly lifted, although her affective state was hardly discussed after the first few weeks of treatment, and it was never an explicit goal of therapy” (p. 333).

BA

The BA case was adapted from Martell et al. (2001, pp. 159–173). The client was a 21-year-old depressed female employed as a technician, and the treatment goal was “teaching her to be more proactive in order to increase the likelihood that her behavior could be positively reinforced.” This first transcript is from Session 4, when the client described attending a holiday gathering at her boyfriend's house and observed his family's happiness and started thinking about how unhappy her own family was, which made her feel sad and lonely.

T: When you were with [his] family and you started to think about how nice his family is and how not-so-nice your own is, do you think you started to disengage a little bit?

C: [nods in agreement]

T: Did thinking a lot about your own family ultimately end up with you missing out on enjoying a good time?

C: Yes, in these situations I'll sit back and not talk. … And, I'll want to leave.

T: Did you leave?

C: Yes, because of that, and because we were both tired.

T: You've become very good at avoiding negative things or getting out of negative situations—you may not be as good at getting into more positive situations. … You get into a TRAP. This stands for Trigger, which, in this case, is your partner's nice family; Response, which, in this case, is feeling lousy and lousy about your own family; and Avoidance-Pattern, which is when you say you start wanting to leave the situation. … So the way to get out of the trap is to use alternate coping, do something different. Maybe staying a little longer even though you feel like leaving, looking around the room to see who wore red on Christmas, or better yet, trying to engage someone in an interesting conversation, anything other than sitting and dwelling.

Here, the therapist clearly goes after activation, introducing TRAPs and TRACs. There is no explicit focus on acceptance (or acceptance-enhancing techniques) that might be relevant to the negative thoughts and feelings. Instead, there is more focus on the consequences of her passive repertoire and the possibility of an alternate repertoire. There is an implied rule offered: Do anything other than sitting and ruminating. An ACT therapist might first implement acceptance strategies directed toward the private events that preoccupied the client (i.e., the ruminative thoughts and negative feelings) and willingness to have those thoughts and feelings while choosing not to sit back. The BA therapist went directly after the new behavior and would likely suggest that the negative private events will dissipate when an interesting conversation is achieved. Notice also how the BA therapist encourages mindful attending to the moment during any activation attempt, which is hinted at in the comment about seeing how many people are wearing red.

Later in therapy (Session 16), the client has been generating ideas for finding a new job and dealing with dental problems, but has not been active in implementing strategies.

T: It seems to me that we can look at any of these life situations as a “trigger.” Even coming to therapy and needing to set an agenda [for the session] is a trigger. Your response is … what would you say your response is?

C: I don't know … hopeless.

T: Okay, so you feel hopeless. What do you do?

C: Well, you're telling me I don't do anything.

T: I'm not exactly saying that you don't do anything, I've seen you work pretty hard during our therapy. What I am saying is that your general style is to get very passive and just complain about problems but wait until something happens apart from you that will fix the situation. Would you agree?

C: Yes, I guess so.

T: So that is your “avoidance pattern” when it comes to these things. So what could get you back on TRAC, with an alternative way to cope?

C: Do it no matter how I feel.

T: I think that might be worth a try, so how can you plan that for this upcoming week?

C: Well, I need to keep looking for a job, and I need to get back to see a dentist.

T: Can you write some of these things on an activity chart and commit to times in the next few days when you'll do them?

This interaction represents typical BA—a situational analysis that identifies avoidance and instruction to activate instead. The client endorses feeling hopeless, but, time is not spent on accepting the feeling and then acting in the face of it, as might occur in ACT; the therapist moves directly to action. Acceptance is a potential by-product of the goal-directed action, but there is no deliberate attempt to foster acceptance, nor is there a focus on language or concern about language use that dictates use of metaphors and experiential exercises rather than straightforward talk.

Subsequently the client saw a dentist (and was prescribed antibiotics) and interviewed for and accepted a new job. At the termination session, the client reported the most important aspect of therapy was learning to be active, no matter what she was feeling.

C: I know that I need to schedule things and just stick to the schedule, and I'll feel better, even when I am feeling lousy.

T: So the activity charts have been helpful?

C: Yes, and recognizing when I avoid things. I know that I just need to keep facing things, because when I avoid them they just get worse.

Note that the client clearly endorses the activation-instead-of-avoidance rationale. Some acceptance is implied (“I just need to keep facing things”), but it is a means to another end—feeling better.

Treatment Efficacy

The history of treatment outcome studies for BA is a true success story for behavior analysis. Early research on Lewinsohn's (1974) original pleasant events scheduling (PES) was mixed at best (Blaney, 1981). After a quiescent period in which PES was subsumed within larger cognitive behavioral treatment packages (e.g., Lewinsohn's “coping with depression” and Beck's cognitive therapy, Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), Jacobson et al. (1996) revived interest in BA with a component analysis of cognitive therapy. This large study (152 clients) compared the BA component of cognitive therapy, BA plus a partial package of cognitive therapy targeting automatic thoughts, and the full cognitive therapy package. Results suggested that a behavioral approach to depressive symptoms was as effective as both cognitive therapy conditions. There were no differences in outcome effectiveness at the end of treatment, despite a large sample, excellent adherence and competence by multiple therapists in all conditions, and a clear bias by the study therapists favoring cognitive therapy. More important, these findings were maintained when evaluated at a 2-year follow-up (Gortner, Gollan, Dobson, & Jacobson, 1998).

This study sparked the development of both BATD (see Hopko, Lejuez, LePage, Hopko, & McNeil, 2003; Lejuez, Hopko, & Hopko, 2001; Lejuez, Hopko, LePage, Hopko, & McNeil, 2001) and current BA. A recent randomized trial compared current BA to cognitive therapy, paroxetine, and placebo (Dimidjian et al., in press). Subjects (N = 241) were randomly assigned, stratified by depression severity, to one of the four conditions. At posttreatment, there were no differences between the three active groups for mildly depressed participants. However, BA and medication outperformed cognitive therapy with moderately to severely depressed participants. Although there were no differences between BA and paroxetine, BA had a significantly lower attrition rate. Thus, BA demonstrated an advantage over pharmacological treatment by retaining more clients and matching its effectiveness without risk for physiological side effects. Jacobson et al. (1996) suggested that cognitive therapy's version of BA performed as well as full cognitive therapy, but Dimidjian et al. (in press) offer evidence that current BA may be a more efficacious treatment for more severely depressed clients. However, it should be noted that in another recently completed large-scale randomized clinical trial, cognitive therapy did as well as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor at posttreatment (DeRubeis et al., 2005) and was better at preventing relapse (Hollon et al., 2005).

Two smaller studies on depression have been conducted using the original version of ACT, called comprehensive distancing (Zettle & Hayes, 1986; Zettle & Rains, 1989). Before we discuss studies that examine comprehensive distancing, it is important to distinguish it from ACT. Comprehensive distancing included many features of ACT. However, it differed in that creative hopelessness played a relatively smaller role and, more important, BA (specifically, PES) was incorporated towards the end of treatment rather than the current focus on values (Zettle, 2005b; Zettle & Hayes, 1989). Interestingly, incorporation of PES included its underlying focus on reducing depressed feelings, as described in the comprehensive distancing manual (Zettle & Hayes, 1989) used by Zettle and Rains:

One approach which has shown a great deal of promise in helping individuals like yourself to feel less depressed [italics added] is to encourage you to maintain a high activity level, particularly in doing things you normally enjoy. Actually what we've focused on so far in allowing you to avoid getting caught up in your own thoughts and feelings should free you up so you'll have more time and energy to devote to enjoyable activities [italics added]. (p. 22)

Thus, comprehensive distancing may be described as a substantial extension of PES that focused first on dismantling the verbal context that supports experiential avoidance before engaging in PES. As comprehensive distancing evolved into ACT, PES and its attached rationale were replaced by values work, and the treatment became more consistent.

Zettle and Hayes (1986) compared three treatments: comprehensive distancing, cognitive therapy without distancing techniques, and full cognitive therapy. Eighteen women were randomly assigned to one of the three groups, and all clients were treated by the first author. Despite including a partial cognitive therapy package to determine the specific role of distancing in cognitive therapy, both cognitive therapy groups were combined for analysis. Clients treated with comprehensive distancing reported significantly less believability of thoughts at posttreatment and significantly less depression at a 2-month follow-up compared to clients in the aggregate cognitive therapy condition (see also Zettle & Hayes, 1987).

This study was followed by a comparison of comprehensive distancing and cognitive therapy in a group therapy setting (Zettle & Rains, 1989). Forty-five women participated and, similar to Zettle and Hayes (1986), three treatment conditions were included: comprehensive distancing, cognitive therapy without distancing, and full cognitive therapy; all groups were led by the first author. Unlike the previous study, however, the cognitive therapy groups were not aggregated for analysis. All groups demonstrated significant decreases in depression, but no differences in treatment efficacy were found at either posttreatment or 2-month follow-up.

Thus, taken together, there is a small data set suggesting that an early and approximate version of ACT tested better than cognitive therapy when administered individually and a comparatively larger study that reported no significant differences when conducted in a group setting. All clients in both studies were women, and all were treated by Robert Zettle; thus generalizations to men and to other therapists less connected with the development of the treatment remain unresolved issues. With regards to ACT, to date there is no randomized outcome research published that has examined its efficacy with respect to depressive clients. Thus, it seems that BA clearly holds an advantage over ACT in terms of published efficacy for the treatment of depression. However, several trials of both ACT and BA for depression (including large-scale efficacy trials of BA adapted for primary-care settings) are underway or have not yet been published, and we expect the database to grow considerably for both treatments over the next few years. Unfortunately not much of this research will be behavior analytic.3

That said, it must also be stated that ACT holds an advantage over BA in terms of several other mental health problems. ACT has been tested for workplace stress management, psychotic symptoms, mathematics anxiety, polysubstance-abusing opiate addicts, chronic smokers, and social anxiety (reviewed in Hayes et al., 2006; Hayes, Masuda, Bissett, Luoma, & Guerrero, 2004). Several of these studies have included measures of depression. An ACT-based group intervention decreased depression for self-harming clients who had been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder compared to a treatment-as-usual control (Gratz & Gunderson, in press). Chronic pain patients, acting as their own controls and receiving ACT-consistent interventions, demonstrated reduced levels of depression that were maintained at a 3-month follow-up (McCracken, Vowles, & Eccleston, 2005). A multiple baseline within-subject design demonstrated reductions in depression among obsessive-compulsive clients (Twohig, Hayes, & Masuda, in press). Finally, a noncontrolled study reported similar reductions in depression among parents of children who had been diagnosed with autism given ACT-based group support (Blackledge & Hayes, in press). BA, in turn, has been studied as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in a case study (Mulick & Naugle, 2004) and a small-group design (Jakupak et al., in press).

Summary and Treatment Implications

In addition to the text below, Table 1 provides a brief synopsis of the similarities and differences between ACT and BA outlined in this paper. (Cognitive therapy, although not the focus of this paper, is included as an additional point of reference because it is the psychosocial treatment for depression that has the largest empirical database.) In BA, clients are told, “Activate and you will feel better” and are provided with instructions for how to do so. Initial compliance with these rules will hopefully lead to stable contact with positive, natural reinforcement, which should then maintain the behavior and the rule following. According to the taxonomy of rule following described by Hayes (Hayes et al., 1999; Hayes & Ju, 1998), rule following in BA moves from pliance (rule following because of socially mediated consequences) and ineffective tracking (following because of a correspondence between the rule and the natural consequences—in BA's conceptualization of depression, the natural consequence being avoidance or escape) to more effective tracking (following a rule because, more often than not, it successfully leads to positive reinforcement). The desired outcome is for the specific tracks (e.g., as identified in the TRAP/TRAC analyses) to become largely contingency governed as natural consequences are contacted, thus, also supporting the general rule (i.e., “To feel better activate using TRAP/TRAC analyses”). It is hoped that this result will be prophylactic against future depression.

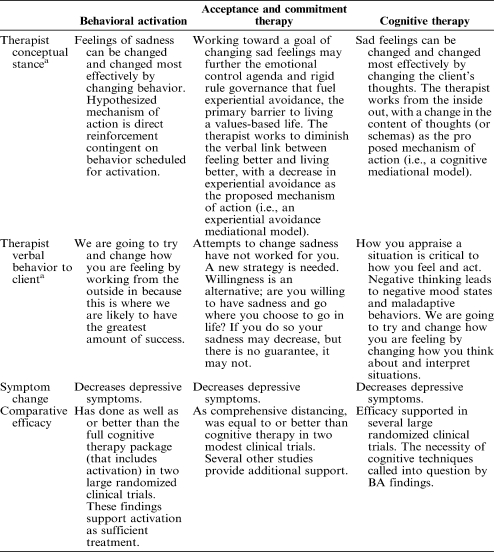

Table 1. A summary of the similarities and differences among behavioral activation, acceptance and commitment therapy, and cognitive therapy.

From an ACT perspective, there is potential concern that strengthening such rule following might unwittingly contribute to a generalized response class of following verbal rules that specify emotional control. Accordingly, across the full duration of therapy, ACT seeks to weaken attempts at verbal control of private events; this includes eliminating changing private events as an explicit goal of treatment. The purpose of ACT is similar to that of BA in that clients should make contact with contingencies in their current environment. The hope is that, when attempts to control private events are suspended and values are clearly discriminated, (a) engagement in overt behavior, as specified in rules derived from values, will be potentiated (augmenting), and (b) the client will be more sensitive to the direct consequences of this behavior, such that (c) rules that are formed will be more accurate and adaptive (tracking).

Thus, ACT differs from BA on theoretical grounds for three reasons. First, as stated earlier, BA can be seen as reinforcing verbal processes that support the control of aversive private events. Second, according to ACT, verbally controlled behavior leads to insensitivity to changes in schedules of reinforcement and may reduce the value of reinforcers. That is, the same way that values may act as augmentals that increase the strength of reinforcers, an avoidance-control agenda may act as an augmental that reduces the value of reinforcers that are associated with the occurrence of negative private events (e.g., when a client reports having had a positive social encounter but indicates that it was “a failure” because he did not feel happy as it occurred or afterward). In other words, verbal processes may prevent and disrupt contact with environmental contingencies that BA suggests will reinforce and maintain behaviors alternative to avoidance. Third, even when environmental contingencies that support active and goal-directed behavior are contacted, ACT would consider such contact to be limited and risk for relapse substantial as long as underlying verbal processes that support experiential avoidance are not addressed. Even an active and goal-directed life will still inevitably supply aversive private experiences that will trigger experiential avoidance.

For this reason, ACT permits the success of activation and exposure treatments but only to a degree. For example, a young college student who strictly follows the rule, “If I avoid emotional expression, then I will not be humiliated, which is good,” may find himself in a specific social situation in which emotional expression is encouraged and supported. Eventually, the person may learn to disclose emotions in this setting. From an ACT perspective, a new rule has not been established; rather, the old rule has been elaborated into “If I avoid emotional expression, then I will not be humiliated, which is good but since Situation A will not bring humiliation I can express emotion.” According to ACT, this may be what BA achieves. This appears to be at least a half step forward from an ACT perspective, in that this rule is less rigid and inflexible than the original, consistent with the ACT notion that experiential avoidance becomes especially problematic when it results in significantly reduced behavioral flexibility (i.e., large portions of the client's repertoire are centered around it). However, this half step forward might lead to a full step backward if the underlying control agenda has simply been reinforced and not weakened. In other words, risk for relapse might be higher. This conceptual concern is not supported by the available long-term follow-up data on BA (or cognitive therapy for that matter), which suggest that changes are relatively robust. It is not entirely clear at the present time how ACT would conceptually account for the positive and persisting effects of BA and cognitive therapy, but BA can conceptually account for the effects of ACT, cognitive therapy, and BA by emphasizing the sufficiency of activation, the common thread among the treatments. The need for additional data addressing the active ingredients of change in these treatments is apparent.

The preceding paragraph also prompts questioning whether ACT's additional verbal strategies are necessary. Efficacy data based on group designs aside, theoretically the choice to use BA or ACT for a depressed client may rest on the role of verbal behavior in a client's problems. Unfortunately, technologies for the assessment of the role of derived stimulus relations and control by verbal rules in individual cases do not yet exist (see Hayes & Follette, 1992, for a full discussion of this issue). ACT authors frequently highlight the apparent ubiquity of verbal behavior (e.g., “Humans swim in a sea of talking, listening, planning, and reasoning,” Hayes, Blackledge, & Barnes-Holmes, 2001, p. 3) as justification for ACT's use, but such broad generalizations are difficult to support empirically. Indeed, a basic premise of behavior analysis has been that most controlling variables are not globally applicable, should be determined experimentally, and are not to be assumed from common sense and experience. Furthermore, another premise has been that a particular focus on verbal behavior and other private events, although they seem causal from the perspective of common sense, may in fact detract from a proper functional assessment of environmental variables (e.g., Skinner, 1953).

There is certainly solid experimental support for many of the basic processes (rule-governed behavior, derived stimulus relations, transformation of stimulus functions) invoked by ACT and described by RFT (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001), and this support is growing. Nonetheless, RFT research preparations do not successfully address the ubiquity of verbal behavior, the question of whether a particular client problem is best conceptualized as verbal, or the question of whether a particular overt behavioral stream is functionally connected to the private verbal behavioral stream that preceded it. RFT theorists acknowledge the difficulty determining whether nonverbal behavior is verbally mediated or contingency shaped on a behavior-by-behavior basis (Hayes, Gifford, Townsend, & Barnes-Holmes, 2001); only a full documentation of the relevant histories involved will reveal the actual sources of control, and of course the distinction is somewhat arbitrary, in that most clinically relevant behavior is multiply controlled.

Given multiple sources of control, it may be more appropriate to take a pragmatic stance and ask if targeting verbal variables over other variables will lead to enhanced outcomes for particular clients. Unfortunately, there is little research to guide this line of questioning. The problem is compounded by the repeated finding that most cognitive and behavioral treatments for depression appear to perform equivalently (Gloaguen, Cottraux, Cucherat, & Blackburn, 1998), and considerable evidence exists to support the notion that nonspecific factors (i.e., provision of a clear treatment rationale with a set of associated techniques offered in the context of a solid therapeutic relationship) are more important in treatment than are specific differences as discussed in this article (Ilardi & Craighead, 1994).

Addis and Jacobson (1996) provide some potentially relevant information about clients for whom BA may or may not work. Examining the data from the component analysis of cognitive therapy (Jacobson et al., 1996), they found that outcome in BA was positively correlated with client response to the BA rationale and early activation assignments, suggesting the importance of events that happen early in treatment. In addition, clients who endorsed more reasons for depression (assessed with the Reasons for Depression self-report questionnaire by Addis, Truax, & Jacobson, 1996), especially reasons that pointed to depression as a character trait or depression in response to existential issues, tended to have poorer outcomes in BA.

Extrapolating from these data, it might be suggested that clients receive ACT if they present with high experiential avoidance4 and many reasons for depression, especially reasons that place the cause of depression in characterological or existential domains, because ACT directly targets verbal reason giving (with cognitive defusion strategies) and existential issues (with values identification and clarification). In addition to using self-report questionnaires, we suggest that the clinician perform some informal assessment to identify the level of fusion with evaluating thoughts and conceptual categories, the level of experiential avoidance (core unacceptable emotions, thoughts, memories, etc.; what are the consequences of having such experiences that the client is unwilling to risk) versus overt behavioral avoidance, and the level of identified values and value-directed behavior. This recommendation may point toward ACT with potentially more difficult clients (those with high fusion, high experiential avoidance, and low values), but this simple heuristic is contradicted by BA's recently demonstrated success with severely depressed rather than mildly depressed individuals (Dimidjian et al., in press).

These recommendations are almost entirely based on theory, group design research, and correlations between questionnaires. Single-case designs are sorely needed in this area. Neither ACT nor BA has provided much of these data for depression (but see Twohig, Hayes, & Masuda, in press). Furthermore, neither have provided much in the form of component analyses, to determine which of their multiple treatment techniques or components are empirically justifiable, when to employ them, and for which client problems. Lastly, there is little research guidance on how to conduct functional assessments of the relevant verbal and nonverbal variables that would guide case conceptualization. Thus, the choice to use ACT or BA, for now, may ultimately rely on clinician preference and familiarity, or perhaps clinician values, and the dangers of relying on clinical judgment are clear (Dawes, 1994; Dawes, Faust, & Meehl, 1989; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). This is a somewhat sad state of affairs, but by no means are ACT or BA treatment developers to blame; the field of behavior analysis as a whole has not addressed the particulars of treatment for outpatient depression.

Assuming a lack of a clear rationale for applying either therapy, starting treatments for depression with BA may be justifiable for a few reasons. First, conservatively speaking, the recent, large, and well-designed BA studies lend it clear empirical support as traditionally defined (although the accumulation of ACT evidence from a variety of sources is compelling). Second, whereas both ACT and BA have been formatted as relatively short-term treatments (e.g., 16 to 20 sessions), because the theoretical rationale and treatment procedures for BA are both less complex than ACT, it would be expected that it would be easier to train and conduct BA (although such a supposition has yet to be empirically tested). Third, practically speaking, it would appear to be far easier and even productive to switch from a BA to an ACT rationale than vice versa. That is, if BA is ineffective, the failure of these early attempts to activate without addressing the internal change agenda (and its supporting verbal context) are ripe material for creative hopelessness. In fact, as per functional analytic psychotherapy (Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991), because these failures occurred during therapy they may make creative hopelessness even more powerful than otherwise. Again, however, we have no data suggesting the utility of ACT with BA treatment failures.

It may be the case that BA is more appropriate, not for easier (less depressed) clients, but for clients with simpler goals; namely, to feel better. For example, it is probably easier to conduct BA in the context of other symptom-reduction approaches (e.g., medications). Of course, one can use ACT with clients on medications, but the rationale becomes trickier and harder to implement. ACT therapists in this situation face the dilemma of trying to change a client in ways the client may not have bargained for. It is our experience that some clients will not achieve creative hopelessness, and persistent attempts to target it may frustrate the client and create ruptures in the therapeutic relationship (see Castonguay, Goldfried, Wiser, Raue, & Hayes, 1996, for a demonstration of how rigid adherence to a particular strategy in cognitive therapy led to similar problems). Thus, if the case is relatively pure depression, the client wants simply to feel better, and there is a short time frame, then the use of ACT's values identification and elaborate acceptance and mindfulness technologies may be incommensurate with overall treatment goals.

Nevertheless, ACT has captivated many therapists because the work offers much more than techniques for symptom reduction. For example, Hayes et al. (1999) note that ACT, as part of a larger effort focused on the RFT analysis of human language and cognition, broadly targets human consciousness and suffering and “is perhaps the most important psychological task we face as a species” (p. 287). Applied to depression treatment, this vision at the least mandates not only status as an empirically supported treatment based on acute-treatment outcomes but superior relapse prevention and quality-of-life data as well, and perhaps data based on idiographic measures of commitment to and activation in valued life domains. This will be no easy task, especially given cognitive therapy's demonstrated success at achieving relapse prevention, at least compared to pharmacotherapy (DeRubeis et al., 2005), and given BA's possible superiority over cognitive therapy. Given ACT's grand vision, it will be interesting to see if it can outperform BA in this arena.

Acknowledgments

We thank Douglas Woods and Gregory Schramka for helpful reviews of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The model for ACT here is based on relational frame theory (RFT; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001), description of which is beyond the scope of this paper and which is somewhat controversial within behavior analysis (e.g., Burgos, 2003; Palmer, 2004; Tonneau, 2001). Our discussion presents the model simply as described by ACT and RFT.

BA holds that the stimuli that trigger avoidance responses in depression may be public or private. However, most of the examples in the BA manual involve private stimuli, and the comparison with ACT is more compelling in terms of private stimuli, so this will be the focus of this paper. We acknowledge the traditional view that avoidance is evoked by public stimuli, and private accompaniments are correlated with the public stimuli but are not functionally related to the avoidance response. Neither BA nor ACT fully endorses this traditional view; BA does somewhat but ACT largely appears to have rejected it in favor of the notion of experiential avoidance, which highlights a functional relation, established historically and contextually, between private stimulation and avoidance responses.