Abstract

The opportunistic human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus survives in a wide range of ecological environments, which demonstrates its ability to adapt to highly variable conditions. Survival and gene expression under various conditions have been extensively studied in vitro; however, little work has been done to evaluate this bacterium in its natural habitat. Therefore, this study monitored the long-term survival of V. vulnificus in situ and simultaneously evaluated the expression of stress (rpoS, relA, hfq, and groEL) and putative virulence (vvpE, smcR, viuB, and trkA) genes at estuarine sites of varying salinity. Additionally, the survival and gene expression of an rpoS and an oxyR mutant were examined under the same conditions. Differences between the sampling sites in the long-term survival of any strain were not seen. However, differences were seen in the expression of viuB, trkA, and relA but our findings differed from what has been previously shown in vitro. These results also routinely demonstrated that genes required for survival under in vitro stress or host conditions are not necessarily required for survival in the water column. Overall, this study highlights the need for further in situ evaluation of this bacterium in order to gain a true understanding of its ecology and how it relates to its natural habitat.

Vibrio vulnificus is an opportunistic human pathogen indigenous to estuarine environments and commonly isolated from fish, shellfish, water, and sediment samples worldwide (3, 11, 25, 43). Waters where this bacterium is found typically have salinities that range from 5 to 35 ppt and temperatures that range from 9 to 31°C (16, 22, 26, 28). However, the prevalence of V. vulnificus at certain temperatures has been shown to be related to the salinity of the environment. At lower salinities, the bacterium can be found over a wide range of temperatures, but as salinity increases, the bacterium is typically found only at higher temperatures (33). Other studies have reported a lack of culturability at temperatures of less then 10°C, at which point the bacterium enters the viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state (27). In addition to being able to survive in a wide range of temperatures and salinities, V. vulnificus can survive for extended periods of time in nutrient-deficient environments, such as the water column, but is also routinely isolated from such nutrient-rich environments as the oyster gut (25).

The wide variety of ecological niches that this bacterium inhabits demonstrates its ability to survive under highly variable conditions, and these physiological conditions have been extensively studied in vitro (10, 15, 29). However, such studies can only replicate a fraction of the biotic and abiotic factors that may be encountered in a natural habitat. Thus, in situ studies using cells constrained in membrane diffusion chambers, particularly involving the VBNC state, have also been conducted in order to examine the survival of V. vulnificus in the environment (27). While such studies are valuable in characterizing the survival of bacteria in natural environments, they generally rely on simple plate counts and offer no insight into the gene expression occurring during growth and/or survival.

Of the few studies that have investigated gene expression in V. vulnificus, most have been conducted under select physiological conditions in an attempt to identify altered niche-related phenotypes on the basis of select gene inactivation (12, 31, 32, 34, 35). However, many traits contribute to ecological survival and such studies are likely to overlook subtle changes that would occur in the bacterium's natural environment. In fact, the wide variety of habitats in which this bacterium resides suggests that numerous variations in gene expression occur in response to changes in environmental conditions. To date, the only studies that have evaluated in situ gene expression by V. vulnificus have involved differences due to temperature, studying gene expression by cells in natural estuarine waters during the summer months (38) or on entry into and resuscitation from the VBNC state during the winter (37). The present study set out to evaluate the effects of both high and moderate salinities on in situ gene expression by V. vulnificus incubated in a natural estuarine environment. Examined were the expression of several stress and putative virulence genes over time and the relationship of gene expression to bacterial survival. Additionally, as the stress response proteins (namely, the alternative sigma factor rpoS and the oxidative stress protein oxyR) are thought to be involved in bacterial survival under stressful conditions (8, 39), in situ gene expression by an rpoS mutant and an oxyR mutant was examined simultaneously with that by the parent strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

V. vulnificus strain C7184/K2 (wild-type) and mutant derivatives AH1 (rpoS; 12) and K853 (oxyR; 17) were grown in heart infusion (HI) broth (Difco, Detroit, MI). Antibiotics (1 μg/ml chloramphenicol [Sigma, St. Louis, MO] for AH1) or additives (80 μg/ml pyruvate [Sigma] for K853) were added in order to maintain the mutations or allow growth, respectively. Cells were grown overnight at room temperature with periodic inversion.

In situ experiments.

Two preparations were created for each strain by inoculating 1 ml of an overnight culture into 50 ml of 1/2 ASW (artificial seawater) (42), generating a 1:50 dilution (final concentration, ca. 107 CFU/ml). Appropriate concentrations of chloramphenicol or pyruvate were added to AH1 and K853 preparations, respectively, to preserve the integrity of the mutations before the cells were placed into the environment. Membrane diffusion chambers (21) were inoculated with 15-ml aliquots of one of the bacterial preparations, with four chambers inoculated for each strain. Two chambers of each strain were placed at a high-salinity site (site 1; temperature and salinity readings of 24°C and 31 ppt), and the remaining two were at a lower-salinity site (site 2; temperature and salinity readings of 26.4°C and 21 ppt). Site 1 was a private-access portion in Banks Channel, NC, and site 2 was located near a public boat ramp at Topsail Sound, NC. At 0 and 30 min and 4, 12, 24, and 48 h, 1 ml was aseptically withdrawn from each chamber. Samples were immediately centrifuged to remove cells from the environmental matrix. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellets were resuspended in RNA Protect (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions and stored at −20°C until RNA extraction was performed. An additional 1 ml was withdrawn at t = 0, 24, 48 h to determine CFU counts on HI agar (with additives as appropriate). Plates were incubated overnight at 30°C.

RNA extraction.

RNA was purified from samples treated with RNA Protect with the TRIzol Max bacterial RNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, with slight modifications that have been shown to increase the pure-RNA yield from V. vulnificus cells (37).

Analysis of gene expression.

The following genes were examined for their expression at each time point sampled: rpoS (alternative sigma factor), groEL (protein chaperone), smcR (V. harveyi luxR homologue), trkA (potassium [K+] uptake), vvpE (zinc metalloprotease), hfq (small protein involved in posttranscriptional regulation), relA (ppGpp synthase), and viuB (iron acquisition). Expression was evaluated by amplifying mRNA with the Access reverse transcription (RT)-PCR system (Promega). The primers used for each of these genes are listed in Table 1. The RT-PCR cycling conditions for groEL, rpoS, smcR, relA, and viuB were as follows: 45°C for 45 min, 94°C for 5 min, and then 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 61°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Cycling conditions were altered slightly for amplification of hfq, trkA, and vvpE as follows: 45°C for 45 min, 94°C for 3 min, and then 40 cycles of 94°C for 40s, 57°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Results presented represent data obtained from two individual chambers for each strain at each salinity site.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for gene expression analysis

| Gene | Primer sequence

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward (5′ to 3′) | Reverse (5′ to 3′) | |

| rpoS | GCAAGATGAAGACATGCGTG | CTTCAACCTGAATCTGGCG |

| groEL | CGCAAGCTATCGTAAATGTGGG | GAGTTCGCAGAGATGGTGCCTAC |

| relA | ACTGGGCGACGTGATGTG | CCAAAGGCCAGCCAATGT |

| smcR | TTCTTGTGGCGACCGTCTTCAAC | CTTCACCACGCTCAATGGCT |

| trkA | GTCAGGTCGCCTTTACTCT | TTCGTCTTCGTTGGTGAG |

| vvpE | ACTGTTTGCCGTCCAATAC | CGGGTGAAGCGGCAGAGT |

| viuB | GGTTGGGCACTAAAGGCAGAT | TCGCTTTCTCCGGGGCGG |

| hfq | AGGGGCAATCTCTACAAG | TCTACTGTGGTTCCTGCT |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Survival of V. vulnificus.

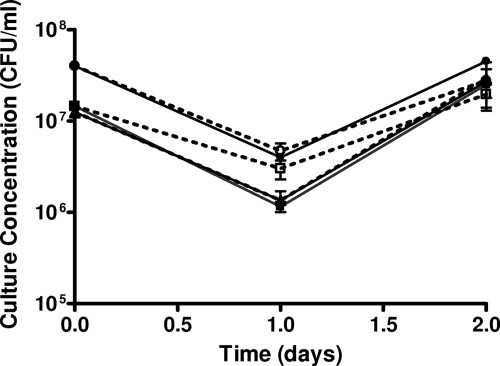

V. vulnificus and two single-gene mutants were analyzed for the ability to survive in situ in the estuarine environment. One mutant (AH1) possesses a mutation in the rpoS gene, which encodes an alternative sigma factor typically involved in stress condition responses (8). The second mutant strain (K853) possesses a mutation in oxyR, which is part of an oxidative stress regulon for proteins involved in stress-induced protection against unrelated stresses (39). Insertion stability studies indicated that both mutations are stable, at least over a 72-h period (data not shown), whether cells were growing in HI broth or incubated in 1/2 ASW. Culture concentrations for all strains were measured during incubation at high- and moderate-salinity sites at 0, 24, and 48 h. Results showed little variation in cell counts over the 48-h study period (Fig. 1). During in situ incubation, a slight decrease in culture concentration was observed in all strains between 0 and 24 h; however, these changes were not significant (P ≤ 0.4496) for any strain at either sampling site. At the high-salinity site, where no recreational use of the water typically occurred, membrane diffusion chambers were left in the water column and sampled for cell concentration after 30 days. This final time point revealed that all strains remained culturable at day 30, although levels had dropped to ca. 105 CFU/ml (data not shown), demonstrating that V. vulnificus cells are able to survive at high concentrations for extended periods of time in natural environments. Indeed, we have cells of V. vulnificus strain C7184 that have been incubated at room temperature in ASW for more than 17 years and still retain a considerable culturable population (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Culture concentrations in chambers at moderate and high salinities. Shown are the concentrations of wild-type and mutant cultures of V. vulnificus incubated in membrane diffusion chambers with high-salinity (31‰) and moderate-salinity (24‰) environments over 48 h. Shown are C7184/K2 at 31 ppt (▪) and 21 ppt (□), K853 at 31 ppt (▴) and 21 ppt (▵), and AH1 at 31 ppt (•) and 21 ppt (○).

Interestingly, comparisons of cell concentrations between the mutants and the parent strain demonstrated no significant differences (P ≥ 0.6745) in survivability at either high or moderate salinity. These results suggest that loss of either rpoS or oxyR function does not have an adverse affect on long-term survival in the water column. It was expected that rpoS, which is known to play a major role in the stress response in other bacteria, may play a role in survival, as it has been shown to regulate several genes that are induced upon incubation in ASW in Escherichia coli (36). However, our results suggest that incubation in estuarine water at warm temperatures (24 to 26°C) may not provide a considerable stress for V. vulnificus, and thus, rpoS may not be essential for survival under these conditions. Survivability studies also indicated that oxyR may not be required for long-term survival of V. vulnificus in these environments. However, while this gene has been shown to be essential for resuscitation of V. vulnificus out of the VBNC state (17), the present studies were conducted when water temperatures were well above the level (10 to 13°C) known to induce this dormancy state in this species. Therefore, differences in long-term survival between this mutant strain and the wild type may only be apparent at colder temperatures.

Gene expression analysis.

It is unknown what mechanisms allow V. vulnificus to survive for extended periods of time in the marine environment. A necessary step in gaining an understanding of the natural ecology of this bacterium is to evaluate gene expression during long-term survival. Thus, the expression of various stress and putative virulence genes was monitored in V. vulnificus over 48 h in high- and moderate-salinity environments. A variety of genes have been shown to play a role in the survival or pathogenesis of V. vulnificus under in vitro and/or in vivo conditions (6, 12, 14, 20), and several of these genes (vvpE, smcR, viuB, rpoS, and trkA) were selected for evaluation of their role in survival in situ. Additionally, because the estuarine environment has been assumed to be a stressful habitat for bacteria due to temperature and salinity fluctuations and the lack of available nutrients, the expression of genes involved in stress and stringent responses (relA, hfq, and groEL) was also examined.

Expression of all eight genes occurred in strain C7184/K2 for at least 4 h after introduction into high-salinity estuarine water, and five of the eight genes remained on through 48 h under these conditions (Table 2). However, the expression of several genes was markedly altered when this strain was incubated at moderate salinity (Table 2), with the most dramatic differences in expression being seen for viuB, trkA, and relA.

TABLE 2.

Gene expression by C7184/K2 over time

| Gene | Expression at high/moderate salinity

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 30 min | 4 h | 12 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| rpoS | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| groEL | +/+ | +/+ | +/− | +/+ | +/+ | −/− |

| smcR | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| relA | +/+ | +/+a | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/+ |

| hfq | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| viuB | +/+ | +/− | +/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| trkA | +/+ | +/+ | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− |

| vvpE | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

One replicate was positive for gene expression, while the other replicate was negative.

Expression of viuB (whose product is involved in siderophore-mediated iron acquisition) dropped below the limit of detection before all other genes at both salinities in the wild-type strain. However, the lack of detection was seen much sooner (30 min) at moderate salinity than at high salinity, where expression ended after 4 to 12 h of incubation (Table 2). These results suggest that viuB may not be required for extended survival in the water column and may instead be used primarily for survival once inside an oyster or human host. As iron levels in seawater are only ∼0.0001 μmol/kg (2), it might be expected that acquisition of iron would be necessary for environmental survival, and viuB expression might be expected to remain on for extended periods of time at both salinities. However, while the role of siderophores has been examined in the presence of serum and in host models (19, 24), we are aware of no research that has explored their role in iron uptake in natural marine environments. Indeed, Panicker et al. (30) demonstrated that only 24% of the environmental V. vulnificus isolates tested possessed viuB, suggesting that alternative iron acquisition systems may be present and necessary for environmental survival.

Another possible explanation for the lack of viuB expression seen throughout most of our study may be related to the expression of the iron regulator Fur. It was recently shown in V. vulnificus that Fur is found in increasing amounts under iron-limiting conditions (18). Additionally, it appears that the activity of Fur in V. vulnificus may differ from that in other organisms. In E. coli, Fur forms a complex with Fe2+, which then binds to consensus sequences upstream of genes encoding siderophores and other proteins involved in iron acquisition, leading to the repression of these genes. However, regulation by Fur in V. vulnificus does not appear to require Fe2+ to bind to these consensus sequences (18). The role of Fur in the regulation of these genes in V. vulnificus is still unknown, but recent research opens the possibility that overexpression of Fur under iron-limiting conditions, such as those present in the marine environment, may lead to the differential expression of genes like viuB. Furthermore, it has been shown that Fur can bind other divalent cations, including zinc (1). Zinc occurs in seawater at approximately 10 times the concentration of iron (2). This potential for competitive binding to Fur may represent an additional or alternative aspect of iron, and thus viuB, regulation.

A third possible explanation for the early cessation of viuB expression may be related to quorum sensing. Recently, new theories as to the role of autoinducers in the environmental survival of bacteria have been proposed. One such theory is “efficiency sensing,” which suggests that autoinducers are used by bacteria as indicators of their external environment (9). Autoinducers are less energetically expensive than other macromolecules, are detected with high sensitivity, and therefore can be used to determine if the environment will allow the return of secreted macromolecules to the bacterium. The ultimate value of siderophores to V. vulnificus lies in the ability of the bacterium to use the iron that has been scavenged by the proteins. Thus, in an open system (such as the water column), the likelihood of a siderophore returning to the bacterium is very low. Therefore, in the efficiency-sensing model, siderophore production would be turned off. This hypothesis gains additional support from our data in that smcR (a V. harveyi luxR homologue) remained on throughout our study at both salinities and in all strains (Tables 2 to 4), suggesting that the bacterium may be constantly testing the surrounding environment.

TABLE 4.

Gene expression by K853 over time

| Gene | Expression at high/moderate salinity

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 30 min | 4 h | 12 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| rpoS | −/− | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| groEL | +/+ | +/+ | +/− | +/+ | +/+ | −/− |

| smcR | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| relA | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+a | −/+ |

| hfq | +/+a | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ |

| viuB | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| trkA | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/− | +/+ | +/− |

| vvpE | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/− |

One replicate was positive for gene expression, while the other replicate was negative.

Differences in viuB expression were also noted between the parent strain and mutant strains, but only at moderate salinity. In the mutant strains, expression of this gene mimicked the high-salinity results, becoming undetectable between 4 and 12 h at both salinities (Tables 2 to 4). These differences may indicate that rpoS and oxyR are involved in viuB expression at some salinities. However, given the possibility that viuB is not involved in environmental iron acquisition, it may be that the observed differences in gene expression between the mutants and the parent strain are related not to salinity but rather to the overall effect of losing a stress response system.

Differential expression of trkA (a regulator of potassium uptake) by C7184/K2 was also observed between the moderate- and high-salinity environments. At moderate salinity, trkA expression dropped below the limit of detection within 4 h (Table 2). This result falls in line with previous research that indicates that bacteria respond immediately to osmotic upshifts by inducing a massive uptake of K+, which is quickly followed by downregulation of Trk and efflux of potassium (4). However, this effect on trkA expression was not observed at high salinity as trkA remained on throughout the study (Table 2) and was, in fact, one of only two genes that remained on at day 30 (data not shown).

Recently, Chen et al. (6) examined the role of trkA in V. vulnificus growth under a variety of K+ concentrations. The use of a trkA mutant demonstrated reduced growth compared to the wild type in media with moderate K+ concentrations (1 to 20 mM), suggesting that trkA is required for normal growth under these conditions. It has been estimated that the concentration of K+ in 35 ppt seawater is around 10.2 mmol/kg (2). Therefore, the K+ levels at the high- and moderate-salinity sites would fall into the “moderate” range, where trkA has been shown to influence growth, indicating that there should be no differences in expression between the two sites. However, these studies were conducted in vitro and it is known that the environment persistence of V. vulnificus at various salinities is dependent upon temperature (33). Examination of the two in situ sampling sites used in this study revealed that the temperature (24.1°C) and salinity (31 ppt) conditions of the high-salinity site would lead to lower levels of V. vulnificus, and these differences in survival are likely correlated with differences in gene expression. Therefore, it is possible that the observed differences in trkA expression between the two sampling sites may be related to the normal survival cycles of the bacterium. Furthermore, it is known that many bacteria, including V. vulnificus, have multiple K+ uptake systems (6, 7). Therefore, as redundant systems are present, the observed differences in the in situ expression of trkA in V. vulnificus may also be linked to the function of other K+ uptake systems, and not necessarily to trkA.

The third gene whose expression differed between the high- and moderate-salinity sites in C7184/K2 was relA, which encodes a synthase for the alarmone ppGpp. At moderate salinity, the expression of relA remained detectable throughout the entire study but dropped below the limit of detection somewhat earlier (by 24 h) at high salinity (Table 2). There is no evidence that the expression of relA is influenced by changing salinities but rather is activated by amino acid and carbon or energy limitation (13). Therefore, the observed differences in relA expression in V. vulnificus may have to do with other physical factors that differed between the sites (i.e., quantities and/or types of nutrients, etc.) rather than salinity.

Differences in relA expression were also observed between the wild-type and mutant strains, but only at high salinity. As with viuB expression, this gene dropped below the limit of detection earlier in the parent (after 12 h) than in the mutant strains (through 24 h; (Tables 2 to 4)). It is difficult to make a direct link between differences in expression and the individual mutations; however, it is possible that having all of the stress response systems intact in the parent strain allows the bacterium to respond to environmental stresses more rapidly than strains that have lost one of those systems.

Overall, the relA results suggest that estuarine waters with moderate to high salinities may not be as stressful for V. vulnificus as might be expected given the involvement of relA in stress responses. This hypothesis is supported by the survival data for the rpoS mutant (discussed above), as well as the expression data for groEL. GroEL is another major molecular chaperone that is activated during stress (i.e., heat, osmotic, or pH stress), when misfolding of proteins can occur (41). Its potential importance in V. vulnificus is evidenced by the two complete copies found in both sequenced strains of the bacterium (at VV1_1259-1260 and VV2_1134-1135 in CMCP6 and at VV3106-3107 and VVA1659-1660 in YJ016). However, in situ expression of this gene dropped below the limit of detection after 24 h at both salinities in all of the strains (Tables 2 to 4), again suggesting that these stress-related factors are not required for the long-term survival of this bacterium in the marine environment. Unfortunately, this assertion is not supported by the rpoS expression data. It was found that this gene remained on throughout the entire study (Table 2), but this does not necessarily negate the hypothesis that the environment is less stressful than once assumed given that rpoS is known to be constitutively expressed in V. vulnificus in vivo (S. Limthammahisorn, C. Arias, and Y. Brady, presented at the 107th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, 2007). Studies are currently under way in our laboratory to quantitatively measure rpoS expression in V. vulnificus under a variety of conditions over time in order to confirm the constitutive expression of this gene.

The remaining genes examined in this study (hfq, vvpE, groEL, and smcR) did not show differences in expression between the sampling sites in the parent strain, and only two of these genes (hfq and vvpE) demonstrated differences in expression between the parent and one or both of the mutant strains. The hfq gene encodes an RNA binding protein that acts as a chaperone for stress-related genes and stimulates rpoS production (8). In situ expression of hfq ceased earlier in both mutants (after 24 h) than in the wild type (on through 48 h). The wide role that hfq plays in the physiology and virulence of bacteria makes it difficult to pinpoint the exact reasons for differences in gene expression (Tables 2 to 4); however, results do suggest that loss of either RpoS or OxyR can lead to differences in gene regulation compared to the parent strain. Studies have shown that hfq regulates rpoS, but there are no data to suggest that changes in rpoS expression influence the expression of hfq. However, the observation that hfq expression is lost in the oxyR mutant while rpoS expression remains on is not unusual, as it has been shown that rpoS continues to be expressed in the absence of hfq, albeit at low levels (5, 23). The use of quantitative RT-PCR will be beneficial in further establishing this rpoS-hfq connection in V. vulnificus.

When examining the expression of vvpE, differences were only found between the parent and one of the mutant strains. vvpE expression in C7184/K2 remained on through 48 h at both salinities (Table 2). However, in the oxyR mutant, vvpE expression stopped between 4 and 12 h at high salinity and between 24 and 48 h at moderate salinity (Table 4). In V. vulnificus, vvpE encodes a protease that is thought to be involved in virulence but is not a definitive virulence factor of this bacterium (14). Research examining the expression of vvpE in vitro showed that its expression is reduced in iron-limited media (reported as ≤1.0 μg/dl) and suggests that iron is required for the efficient transcription of vvpE (40). However, these results are not supported by our in situ expression data, which show that, even at the extremely low iron concentrations that are found in the marine environment, vvpE expression remains on for extended periods. These results once again highlight the marked differences in gene expression between in vitro and in situ studies.

Overall, our study highlights the obvious need for in situ examination of gene expression in V. vulnificus. The environmental expression and regulation of genes are undoubtedly complex, and while in vitro studies have significant value for indicating genes and pathways that are important for V. vulnificus survival, they are unable to adequately mimic what actually occurs in the natural environment. This is evidenced by the differences found between this in situ study of gene expression and previously conducted studies examining the involvement of singular genes under in vitro conditions (6, 40). Furthermore, this study demonstrated that previous assumptions about the stressful nature of the estuarine environment may also be inaccurate, at least to some degree. This was particularly evident when evaluating the survival of the rpoS mutant strain, where results showed that loss of this stress system did not adversely affect the long-term (30 days) survival of V. vulnificus. It is likely, however, that the conditions under which survival was tested in this study did not stress the bacterium but that other changes in the natural environment (higher or lower salinity, pH, temperature, etc.) may provide sufficient stresses for which rpoS would be required. For this reason, we are continuing such studies in this laboratory in an attempt to better understand how V. vulnificus relates to its natural habitat.

TABLE 3.

Gene expression by AH1 over time

| Gene | Expression at high/moderate salinity

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 30 min | 4 h | 12 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| groEL | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | ++ | −/− |

| smcR | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| relA | +/+ | +/+a | +/+ | +/+a | +/+ | −/+ |

| hfq | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| viuB | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| trkA | +/+ | +/+ | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− |

| vvpE | −/− | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

One replicate was positive for gene expression, while the other replicate was negative.

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared under award NA05N054781244 from NOAA, U.S. Department of Commerce.

The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations in this report are ours and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Althaus, E. W., C. E. Outten, K. E. Olson, H. Cao, and T. V. O'Halloran. 1999. The ferric uptake regulation (Fur) repressor is a zinc metalloprotein. Biochemistry 38:6559-6569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson, M. J., and C. Bingman. 1998. Elemental composition of commercial seasalts. J. Aquaric. Aquat. Sci. 8:39-43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisharat, N., V. Agmon, R. Finkelstein, R. Raz, G. Ben-Dror, L. Lemer, S. Soboh, R. Colodner, D. N. Cameron, D. L. Wykstra, D. L. Swerdlow, and J. J. Farmer III. 1999. Clinical, epidemiological, and microbiological features of Vibrio vulnificus biogroup 3 causing outbreaks of wound infection and bacteraemia in Israel. Lancet 354:1421-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bremer, E., and R. Krämer. 2006. Coping with osmotic challenges: osmoregulation through accumulation and release of compatible solutes in bacteria, p. 79-98. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 5.Brown, L., and T. Elliott. 1996. Efficient translation of the RpoS sigma factor in Salmonella typhimurium requires host factor I, an RNA-binding protein encoded by the hfq gene. J. Bacteriol. 178:3763-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, Y. C., Y. C. Chuang, C. C. Chang, C. L. Jeang, and M. C. Chang. 2004. A K+ uptake protein, TrkA, is required for serum, protamine, and polymyxin B resistance in Vibrio vulnificus. Infect. Immun. 72:629-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dosch, D. C., G. L. Helmer, S. H. Sutton, F. F. Salvacion, and W. Epstein. 1991. Genetic analysis of potassium transport loci in Escherichia coli: evidence for three constitutive systems mediating uptake of potassium. J. Bacteriol. 173:687-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2000. The general stress response in E. coli, p. 161-178. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 9.Hense, B. A., C. Kuttler, J. Müller, M. Rothballer, A. Hartmann, and J. U. Kreft. 2007. Does efficiency sensing unify diffusion and quorum sensing? Nat. Rev. Biol. 5:230-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris-Young, L., M. L. Tamplin, W. S. Fisher, and J. W. Mason. 1993. Effects of physicochemical factors and bacterial colony morphotype on association of Vibrio vulnificus with hemocytes of Crassostrea virginica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1012-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Høi, L. J. L. Larsen, I. Dalsgaard, and A. Dalsgaard. 1998. Occurrence of Vibrio vulnificus biotypes in Danish marine environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hülsmann, A., T. M. Roche, I. S. Kong, H. M. Hassan, D. M. Beam, and J. D. Oliver. 2003. RpoS-dependent stress response and exoenzyme production in Vibrio vulnificus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6114-6120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain, V., M. Kumar, and D. Chatterji. 2006. ppGpp: stringent response and survival. J. Microbiol. 44:1-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong, K. C., H. S. Jeong, J. H. Rhee, S. E. Lee, S. S. Chung, A. M. Starks, G. M. Escudero, P. A. Gulig, and S. H. Choi. 2000. Construction and phenotypic evaluation of a Vibrio vulnificus vvpE mutant for elastolytic protease. Infect. Immun. 68:5096-5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaspar, C. W., and M. L. Tamplin. 1993. Effects of temperature and salinity on the survival of Vibrio vulnificus in seawater and shellfish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2425-2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaysner, C. A., C. Abeyta, Jr., M. M. Wekell, A. DePaola, R. F. Stott, and J. M. Leitch. 1987. Virulent strains of Vibrio vulnificus isolated from estuaries of the United States west coast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:1349-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong, I.-S., T. C. Bates, A. Hüslmann, H. Hassan, B. E. Smith, and J. D. Oliver. 2004. Role of catalase and oxyR in the viable but nonculturable state of Vibrio vulnificus. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 50:133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, H. J., S. H. Bang, K. H. Lee, and S. J. Park. 2007. Positive regulation of fur gene expression via direct interaction of Fur in a pathogenic bacterium, Vibrio vulnificus. J. Bacteriol. 189:2629-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litwin, C. M., T. W. Rayback, and J. Skinner. 1996. Role of catechol siderophore synthesis in Vibrio vulnificus virulence. Infect. Immun. 64:2834-2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDougald, D., S. A. Rice, and S. Kjelleberg. 2001. SmcR-dependent regulation of adaptive phenotypes in Vibrio vulnificus. J. Bacteriol. 183:758-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McFeters, G. A., and D. G. Stuart. 1972. Survival of coliform bacteria in natural waters: field and laboratory studies with membrane diffusion chambers. Appl. Microbiol. 24:805-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motes, M. L., A. DePaola, D. W. Cook, J. E. Veazey, J. C. Hunsucker, W. E. Garthright, R. J. Blodgett, and S. J. Chirtel. 1998. Influence of water temperature and salinity on Vibrio vulnificus in northern Gulf and Atlantic Coast oysters (Crassostrea virginica). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1459-1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muffler, A., D. D. Traulsen, D. Fischer, R. Lange, and R. HenggeAronis. 1997. The RNA-binding protein HF-1 plays a global regulatory role in expression of the σS subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:297-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okujo, N., T. Akiyama, S. Miyoshi, S. Shinoda, and S. Yamamoto. 1996. Involvement of vulnibactin and exocellular protease in utilization of transferrin- and lactoferrin-bound iron by Vibrio vulnificus. Microbiol. Immunol. 40:595-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliver, J. D. 2006. Vibrio vulnificus, p. 349-366. In F. L. Thompson, B. Austin, and J. Swing (ed.), Biology of vibrios. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 26.Oliver, J. D. 2006. Vibrio vulnificus, p. 253-276. In S. Belkin and R. R. Colwell (ed.), Oceans and health: pathogens in the marine environment. Springer Science, New York, NY.

- 27.Oliver, J. D., F. Hite, D. McDougald, N. L. Andon, and L. M. Simpson. 1995. Entry into, and resuscitation from, the viable but nonculturable state by Vibrio vulnificus in an estuarine environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2624-2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Neill, K. R., S. H. Jones, and D. J. Grimes. 1992. Seasonal incidence of Vibrio vulnificus in the Great Bay estuary of New Hampshire and Maine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3257-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paludan-Müller, C., D. Weichart, D. McDougald, and S. Kjelleberg. 1996. Analysis of starvation conditions that allow for prolonged culturability of Vibrio vulnificus at low temperature. Microbiology 142:1675-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panicker, G., M. C. Vickery, and A. K. Bej. 2004. Multiplex PCR detection of clinical and environmental strains of Vibrio vulnificus in shellfish. Can. J. Microbiol. 50:911-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paranjpye, R. N., and M. S. Strom. 2005. A Vibrio vulnificus type IV pilin contributes to biofilm formation, adherence to epithelial cells and virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:1411-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park, K. J., M. J. Kang, S. H. Kim, H. J. Lee, J. K. Lim, S. H. Choi, S. J. Park, and K. H. Lee. 2004. Isolation and characterization of rpoS from a pathogenic bacterium, Vibrio vulnificus: role of σS in survival of exponential-phase cells under oxidative stress. J. Bacteriol. 186:3304-3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Randa, M. A., M. F. Polz, and E. Lim. 2004. Effects of temperature and salinity on Vibrio vulnificus population dynamics as assessed by quantitative PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5469-5476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhee, J. E., J. H. Rhee, P. Y. Ryu, and S. H. Choi. 2002. Identification of the cadBA operon from Vibrio vulnificus and its influence on survival to acid stress. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 208(2):245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhee, J. E., H. G. Jeong, J. H. Lee, and S. H. Choi. 2006. AphB influences acid tolerance of Vibrio vulnificus by activating expression of the positive regulator CadC. J. Bacteriol. 188:6490-6497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rozen, Y., T. K. Van Dyk, R. A. LaRossa, and S. Belkin. 2001. Seawater activation of Escherichia coli gene promoter elements: dominance of rpoS control. Microb. Ecol. 42:635-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith, B., and J. D. Oliver. 2006. In situ and in vitro gene expression by Vibrio vulnificus during entry into, persistence within, and resuscitation from the viable but nonculturable state. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1445-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, B., and J. D. Oliver. 2006. In situ gene expression by Vibrio vulnificus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2244-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Storz, G., and M. Zheng. 2000. Oxidative stress, p. 47-60. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 40.Sun, H. Y., S. I. Han, M. H. Choi, S. J. Kim, C. M. Kim, and S. H. Shin. 2006. Vibrio vulnificus metalloprotease VvpE has no direct effect on iron-uptake from human hemoglobin. J. Microbiol. 44:537-547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winans, S. C., and J. Zhu. 2000. Roles of cell-to-cell communication in confronting the limitations and opportunities of high population densities, p. 261-272. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 42.Wolf, P., and J. D. Oliver. 1992. Temperature effects on the viable but non-culturable state of Vibrio vulnificus. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 101:33-39. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright A. C., R. T. Hill, J. A. Johnson, M. Roghman, R. R. Colwell, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 1996. Distribution of Vibrio vulnificus in the Chesapeake Bay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:717-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]