Abstract

Molecular analysis of the amo gene cluster in Nitrosococcus oceani revealed that it consists of five genes, instead of the three known genes, amoCAB. The two additional genes, orf1 and orf5, were introduced as amoR and amoD, respectively. Putative functions of the AmoR and AmoD proteins are discussed.

Nitrosococcus oceani ATCC 19707 is a marine aerobic bacterium that belongs to the class Gammaproteobacteria in the order Chromatiales (the purple sulfur bacteria). Its complete genome sequence was published recently (15). In such ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB), ammonia oxidation proceeds in two consecutive steps. First, ammonia is converted to hydroxylamine via the multisubunit, membrane-bound enzyme ammonia monooxygenase (AMO) in the following reaction: NH3 + 2e− + O2 + 2H+ → NH2OH + H2O (10). The subsequent oxidation of hydroxylamine to nitrite is facilitated by the soluble periplasmic enzyme hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO): NH2OH + H2O → NO2− + 5H+ + 4e− (10). The oxidation of hydroxylamine to nitrite yields four electrons, of which two are returned to the upstream monooxygenase reaction and two are the sole source for generating useable energy and reductant. The mechanism of returning the electrons to AMO is unknown (2).

AMO is encoded by at least three contiguous genes, amoCAB, arranged in a gene cluster that is conserved in all investigated genomes of AOB (3, 8, 12, 14, 15, 20-22). Prior work had identified a conserved open reading frame (ORF) following the terminator downstream of the single cluster of amoCAB genes in N. oceani (1, 20). A recent analysis of available genome sequences revealed that all amo gene clusters in betaproteobacterial AOB (beta-AOB) genomes, which contain two or three copies of nearly identical gene clusters, are actually succeeded by two conserved ORFs, orf4 and orf5, except for the amo-hao supercluster in Nitrosospira multiformis (2, 12, 22). In contrast, the terminator downstream of the amoB gene in gammaproteobacterial AOB (gamma-AOB) is succeeded only by the orf5 gene (1), which is conserved at the levels of DNA and protein sequence in all AOB. Our recent analysis of the N. oceani genome sequence revealed that the intergenic region between the amoB terminator and orf5 did not contain a promoter consensus sequence. Furthermore, examination of upstream flanking sequence of the N. oceani amoCAB cluster revealed an additional 213-bp ORF (orf1) that has no homologue in the nonredundant GenBank database including the published (8, 22) and unpublished (12) genomes of beta-AOB. The aforementioned gene structure differences between gamma- and beta-AOB indicate a possible divergent expression of amo genes in gamma- and beta-AOB, which may correspond to their respective niche adaptation in the environment (e.g., gamma-AOB are restricted to marine oligotrophic environments).

In this paper, we report that the orf1 and orf5 genes are cotranscribed with amoCAB in N. oceani, designate these ORFs as amoR and amoD, respectively, and propose that these five genes constitute the gamma-AOB-typical amo operon, amoRCABD.

In our experiments, N. oceani C-107 ATCC 19707 (18, 25) was grown in artificial seawater as 200- to 400-ml batch cultures in 2-liter Erlenmeyer flasks for 3 weeks at 30°C in the dark without shaking as described previously (1). Genomic DNA was isolated from cells in stationary growth phase using a Wizard genomic DNA (gDNA) purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For RNA preparations, N. oceani cells were harvested at mid-exponential to late exponential growth phase and resuspended for 24 h prior to RNA isolation in 200 ml of fresh marine medium. RNA was isolated using a Fast RNA Pro Blue kit (Q-Biogene, Solon, Ohio) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Before cDNA synthesis, the RNA preparations were treated with RNase-free RQ1 DNase (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Northern hybridization.

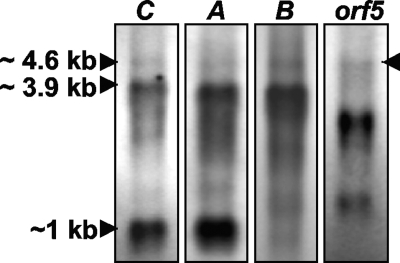

Approximately 2 μg/lane of total RNA was resolved by electrophoresis at 4.5 V/cm for 5 to 6 h on 0.9% agarose gel made with 1× MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) buffer and 6% formaldehyde. An ethidium bromide-stained 9-kb RNA ladder (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used as a size estimate. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled double-stranded DNA probes based on amoC, amoA, amoB, and orf5 were generated using a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol, with specific primers (Biosynthesis, Lewisville, TX) (Table 1) and approximately 50 ng of gDNA as the template. Hybridizing RNA fragments were detected using anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibodies (Boehringer Mannheim) and the alkaline phosphatase chemiluminescent substrate CSPD (Roche) according to the manufacturers’ guidelines and visualized with autoradiography film. The three probes were designed to target the three currently known genes in the amo gene cluster, amoC, amoA, and amoB (14) (see Fig. 3A), and each hybridized to two RNAs of approximately 3.9 kb and 4.6 kb (Fig. 1, lanes C, A, and B). This means that N. oceani expresses two different polycistronic transcripts that contain the amoCAB genes. In addition, hybridization to individual amoC and amoA transcripts was observed, which had been predicted before (1). A comparison with the genome sequence (15) revealed that the smaller (3.9-kb) transcript extended from a transcriptional start point (TSP) approximately 600 bp upstream of the amoC gene to the intrinsic transcriptional terminator we identified downstream of amoB and included the amoCAB genes. Surprisingly, the probe designed to target the orf5 gene also hybridized to the larger 4.6-kb transcript but not to the shorter one (Fig. 1, lane 4). While the intensity of the 4.6-kb band was rather low, the presence of the transcript and residence of orf5 on this transcript were verified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (see below). Thus, we conclude that the orf5 gene is expressed together with the amoCAB genes and resides on a transcript that begins at the same TSP as the shorter transcript, extends beyond the amoB terminator, and ends at a terminator downstream of orf5. Because (i) there were two transcripts with only the larger one including the orf5 gene, (ii) the larger band was of lesser intensity than the smaller band, and (iii) the in silico size difference between amoCAB and amoCAB-orf5 transcripts accounted for the size difference between the smaller and the larger bands in the Northern blot (Fig. 1), we propose that orf5 is expressed by partial read-through of the amoB terminator as a member of the amo operon. Because orf5 is ancestral to the orf4 genes found in beta-AOB (see below) and orf4 is missing in gamma-AOB, we designate this gene amoD. Both transcripts contained a leader sequence of approximately 0.6 kb that is large enough to contain the small orf1 gene that we identified in silico upstream of amoC.

TABLE 1.

Primers

| Purpose and target | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Northern analysis (Fig. 1) | ||

| amoC | 5′-TGCCTGGCGTGGCATGTGGTTAG-3′ (forward) | |

| 5′-AATAACCCAACGCCATAAACAACCCA-3′ (reverse) | ||

| amoA | 5′-GCTAAAGTCTTTAGAACGTTGGA-3′ (forward) | |

| 5′-TCACCTGCTAACACCCCTAGCGT-3′ (reverse) | ||

| amoB | 5′-TATCAGCATGACGGTTGAAATCAC-3′ (forward) | |

| 5′-TCTCATTCCCCTCTGGATCAAC-3′ (reverse) | ||

| orf5 (amoD) | 5′-AGCTGCCTTGTATCGTTTGGA-3′ (forward) | |

| 5′-TGGTAAAATCGGTATCAAGCTCA-3′ (reverse) | ||

| Primer extension (Fig. 2) | ||

| amoC leader | X1 | 5′-TGGCTACGCTTATTCTTCAAGGACCCCGA-3′ |

| RT-PCRs and PCR from gDNA (Fig. 3B and C) | ||

| amoC upstream (lanes 2) | tspF | 5′-GGTTGCTTGCCATAAAGCCGA-3′ |

| R-CR | 5′-CTACAGCTCTACTAGTTGCAGCCATATTGATAGCCTCCT-3′ | |

| amoR-amoC intergenic spacer (lanes 3) | R-CF | 5′-AAAAGCTTAATGGTGCCCCAAGCTCGTGGGCGT-3′ |

| R-CR | 5′-CTACAGCTCTACTAGTTGCAGCCATATTGATAGCCTCCT-3′ | |

| amoC-amoA intergenic spacer (lanes 4) | C-AF | 5′-TTAGCGAAGGGTTGAATAGAAGGG-3′ |

| C-AR | 5′-AGTGCACTCATTAAACCTGCCCTCC-3′ | |

| amoA-amoB intergenic spacer (lanes 5) | A-BF | 5′-CCGCTGGTTCTCCAAGGACTAC-3′ |

| A-BR | 5′-TCGAACGAGGGACGAACATACCAT-3′ | |

| amoB-orf5 (amoD) intergenic spacer (lanes 6) | B-DF | 5′-CCTATCGGCGGTCCATTAGTTCCCA-3′ |

| B-DR | 5′-CCCCATGGGCCATGGCGGAAGT-3′ | |

| 16S rRNA gene (lanes 2-6) | F1-16Sa | 5′-GTTTGATCATGGCTCAGATTG-3′ |

| R2-16Sb | 5′-CACTGGTGTTCCTTCTTCCGATA-3′ |

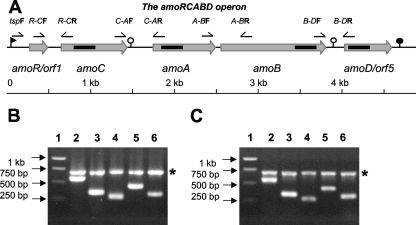

FIG. 3.

Map of the amo gene cluster based on the genome sequence of N. oceani ATCC 19707 (A) and PCR amplification of intergenic regions in the amo gene cluster using cDNA (B) and gDNA (C) as templates. (A) The locations of primers used for amplification of intergenic sequence from cDNA are indicated above the map, and the locations of the sequence complementary to probes used for Northern analysis are indicated as horizontal bars within the arrows that indicate length and location of the genes in the amo gene cluster. Transcriptional start sites and terminators are indicated by flags and circles, respectively. Open circles indicate leaky terminators. (B and C) cDNA and gDNA, respectively, were PCR amplified with the primers indicated in panel A and listed in Table 1. Each reaction mixture also included primers for amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. Lane 1, ladder; lane 2, tspF and R-CR; lane 3, R-CF and R-CR; lane 4, C-AF and C-AR; lane 5, A-BF and A-BR; lane 6, B-DF and B-DR.

FIG. 1.

Northern hybridization analysis using probes based on the amoC, amoA, amoB, and orf5 genes. The sizes of the observed bands are based on a 9-kb RNA ladder. The blot with the probe targeting orf5 yielded only the larger (4.6-kb) band.

Primer extension analysis.

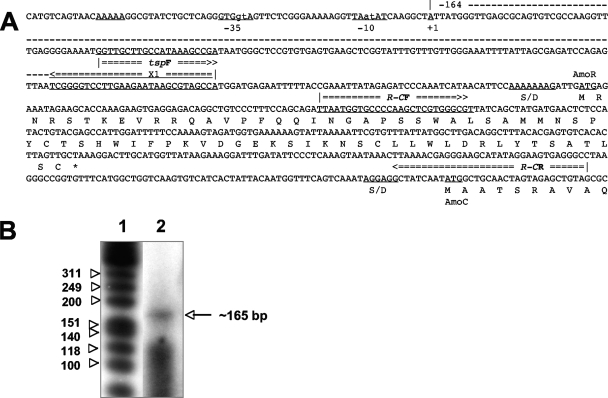

To verify these conclusions, we conducted primer extension experiments to determine the transcriptional start point as well as RT-PCR to confirm the residence of amoD on the larger of the two observed transcripts. To this end, a synthetic 29-mer oligonucleotide, X1 (Table 1; Fig. 2A), was 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA; specific activity, 3,000 Ci mmol−1) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega). X1 was complementary to positions 91 to 63 in the nucleotide sequence upstream of orf1 (Fig. 2A). Primer extension with total RNA was conducted using SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The extension products were electrophoresed in a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide 10- by 10-cm minigel, exposed to a PhosphorImager screen, and analyzed with molecular imager FX and Quantity One image analysis software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). A 5′-end-labeled FX174 HinfI DNA marker (Promega) was used as a size estimate. The resulting cDNA product was 160 to 180 nucleotides (Fig. 2B) and identified the transcriptional start point between nucleotides 223 and 232 upstream of the translational start for orf1 (Fig. 2A). The −10 and −35 consensus sequences of the putative operon promoter were preceded by an A track (Fig. 2A), which is known to enhance transcription (9). In contrast to beta-AOB, where the distal amo promoter is located 166 nucleotides upstream of amoC (6), the operon promoter identified in N. oceani is much further upstream of the amoC gene, thereby generating a leader sequence of at least 600 bp. In addition to the identified orf1, this leader contained 220 to 230 nucleotides of untranslated RNA located upstream of orf1. While the function of orf1 and the significance of the 5′ untranslated region were outside the scope of this study, the cotranscription of orf1 with the amoCAB genes, its size and predicted topology as a small cytoplasmic alpha-helical protein (using PSIPRED [7]), and its uniqueness to nitrosococci suggest a regulatory involvement in ammonia catabolism of gamma-AOB. For these reasons, we consider the orf1 gene a member of the amo operon in N. oceani and designate it as amoR.

FIG. 2.

Primer extension experiment performed to identify the TSPs of the two transcripts observed in Northern analysis (Fig. 1). (A) Annotated sequence upstream of the amoC gene, including orf1 (amoR). (B) Lane 1, single-stranded DNA ladder; lane 2, extension product obtained with primer X1 (see panel A and Table 1).

RT-PCR.

To test our hypothesis that amoR and amoD are part of the amo mRNA, specific primers were designed to amplify the four intergenic regions of the predicted amo operon (Fig. 3A) and an additional fragment that included the putative TSP, the entire amoR gene, and the 5′ end of amoC. The target positions and the sequences of the primers are provided in Fig. 3A and Table 1, respectively. The primer tspF was selected based on PCR amplifications of the cDNA preparations with several tandem forward primers paired with the same reverse primer, R-CR (data not shown). The most upstream oligonucleotide primer that resulted in a high-intensity PCR product was selected as primer tspF for the final multiplex PCR.

First-strand cDNA synthesis from N. oceani total RNA was carried out with SuperScript II (Invitrogen) and random nonamer primers according to the manufacturer's protocol. Second-strand synthesis was conducted in 100-μl reaction mixtures with the entire volume of the previous RT reaction and 15 U of Klenow fragment (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

All final multiplex PCR assays were carried out using GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase (Promega) with one of the following templates: (i) 8 to 10 ng of the cDNA, (ii) DNase-treated RNA preparations obtained before the reverse transcription for the negative controls, (iii) approximately 10 ng of gDNA as a positive control. Primers targeting the 16S ribosomal sequence were included as an internal standard in every multiplex PCR amplification reaction, including the positive and the negative controls. Negative-control PCRs did not result in any PCR products, which indicated the absence of DNA carryover in these preparations (data not shown). Positive-control PCRs resulted in bands of the expected sizes (Fig. 3C), indicating the specificity of the primers. Results of multiplex PCR assays conducted with cDNA as the template are presented in Fig. 3B. Amplification of the upstream leader sequence using tspF (Table 1; complementary to nucleotide positions 560 to 539 upstream of the amoC start codon) and the reverse primer R-CR (Table 1; complementary to nucleotide positions −12 to + 26 with respect to the amoC start codon) resulted in an approximately 585-bp band (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Amplification of the amoR-amoC intergenic region was conducted with forward primer R-CF (Table 1, complementary to nucleotide positions + 56 to + 82 within amoR), and the reverse primer R-CR yielded a PCR product of 347 bp (Fig. 3B, lane 3). These results indicate that amoC resides on a transcript with a leader of at least 600 bp including the amoR gene; therefore, amoR and amoC are transcriptionally linked. Amplification of the amoC-amoA and amoA-amoB intergenic spacers resulted in 290-bp and 450-bp bands, respectively (Fig. 3B, lanes 4 and 5). This confirms that, similarly to beta-AOB (19), the three amoCAB genes reside on a common transcript in N. oceani and that all four amplicons (Fig. 3B, lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5) originated from one or both transcripts observed in the Northern hybridization experiment (Fig. 1).

To investigate the difference between the two observed transcripts, the amoB-amoD intergenic spacer was amplified with forward primer B-DF, which targets the C terminus of amoB, and reverse primer B-DR, which is complementary to the N terminus of amoD. The observed band of ∼330 bp (Fig. 3B, lane 6) indicates that amoB and amoD are transcriptionally linked, in that the amoRCAB transcript extends beyond the amoB terminator, the amoB-amoD intergenic spacer, and the amoD gene and terminates at an in silico-identified rho-independent terminator downstream of amoD (ΔG = −35.3 kcal/mol; start at nucleotide 636,765 in the N. oceani genome sequence; GenBank no. CP000127 [15]), resulting in a 4.6-kb amoRCABD transcript as observed in the Northern hybridization experiment (Fig. 1).

AmoR and AmoD sequence comparison and analysis.

Sequence similarities of AmoR and AmoD with proteins in the nonredundant database were investigated initially using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST program (1). Protein sequences were also analyzed with the PSORT (19), PSIPRED (7), and Phobius (http://phobius.cgb.ki.se/ [13]) servers to identify the secondary structure and hydrophobic domains that could serve as signal peptides for export into the periplasm or constitute membrane-spanning domains.

None of the searched databases contained a sequence with significant similarity to the AmoR protein; hence, this protein appears to be unique to Nitrosococcus. The AmoR ORF is preceded by a Shine-Dalgarno sequence (Fig. 2A), and the protein is predicted to be cytoplasmic (19). Its sequence of 71 amino acids (Fig. 2A) contains three small helices of nine, four, and nine amino acid residues at the N terminus, whereas the C terminus contains a larger helical domain of 19 residues. Using a combination of sequence and predicted structure of the AmoR protein for a search of the PDB (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do), the N-terminal folding domain of frizzled-related protein 3 (PDB entry 1ijxA0) was found to be nearly identical in its fold and 23% identical to primary sequence of AmoR, extending from residue 25 to 105 (126 residues total). The deduced AmoR protein sequence contains three cysteine residues that are not part of a known coordination motif. By analogy to the structure of frizzled-related protein 3 (1ijxA0), cysteine 37 and cysteine 71 of AmoR could form a disulfide bond. Thus, AmoR could serve as a cytoplasmic redox sensor in that this disulfide bond would lock AmoR into a particular reactive secondary structure if the cytoplasm becomes less reducing. The N terminus of frizzled-related protein 3 is involved in protein-protein interactions. Based on this analogy and the fact that the amoR gene is a member of the amo operon, we speculate that the AmoR protein participates in the regulation of ammonia catabolism in Nitrosococcus. Experiments have been initiated to test this hypothesis.

A multiple sequence alignment was produced from a total of 25 (20 full-length and 5 partial) available protein sequences using the deduced full-length AmoD protein sequence from N. oceani ATCC 19707, respective BLAST hits retrieved from the GenBank/EMBL database, and unpublished genome sequences using ClustalX version 1.83 (24). Based on this alignment, a distance neighbor-joining tree was constructed with the BioNJ function in PAUP version 4.10b (23) and used as a guide tree for manual refinement of the ClustalX alignment. Sources for the protein sequences from AOB and other organisms used in the alignments are indicated in the presented phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4). The alignment was subjected to a Bayesian inference of phylogeny (MrBayes version 3.0b4; http://mrbayes.scs.fsu.edu) using four equally heated Markov chains over 1,000,000 generations in three independent runs. The searches were conducted assuming an equal or a gamma distribution of rates across sites, sampling every 100th generation and using the Whelan and Goldman empirical amino acid substitution model (26). A 50% majority rule consensus phylogram was constructed that displayed the mean branch lengths and posterior probability values of the observed clades.

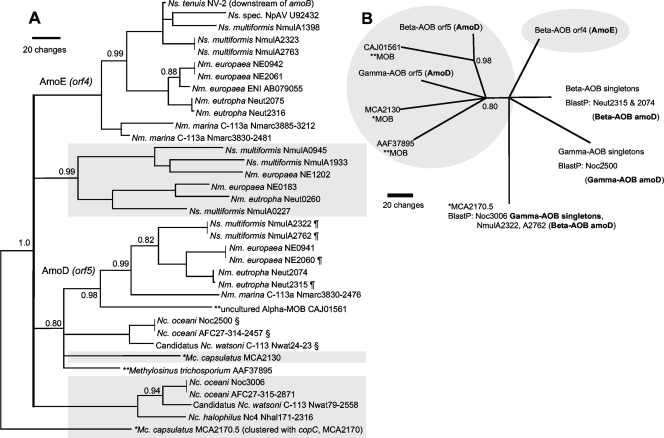

FIG. 4.

Unrooted phylogenetic consensus trees constructed after Bayesian analysis of an alignment of available protein sequences homologous to AmoD (orf5) and AmoE (orf4). Posterior probability values smaller than 1.0 are given at the nodes; branch lengths reflect the evolutionary distance based on the standard provided for 20 changes over time. (A) Labels indicate the sequence source. amoD (pmoD) and amoE genes are clustered with the structural amoCAB and pmoCAB genes, whereas shaded boxes identify the singleton status of amoD and amoE in the source genome. §, a homologue of the multicopper oxidase, MCA2129, is located upstream of the amo gene cluster in gamma-AOB; ¶, orf5 (amoD) is located between amoE and copC in beta-AOB. Structural analysis identified AmoD and AmoE as periplasmic membrane proteins. (B) Unrooted star tree presenting the relationships between major clades. BlastP top hits are provided in support of our hypothesis that amoE and singleton genes were derived from amoD by duplication (see the text). Abbreviations: Ns., Nitrosospira; Nm., Nitrosomonas; Nc., Nitrosococcus; Mc., Methylococcus (indicated with an asterisk). **, alpha-MOB.

It has been reported that the gene (orf5) encoding the AmoD protein in beta-AOB is in a tandem arrangement with another gene, orf4 (2, 15, 20). The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4) rooted in the AmoD homologue, which is expressed from the gene cluster that encodes particular methane monooxygenase (pmo) in the alphaproteobacterial methanotroph Methylosinus trichosporium, demonstrates that all orf4 and orf5 genes are homologues, whether they are part of amo and pmo gene clusters in AOB and methane-oxidizing bacteria (MOB), respectively, or singletons.

Very recent work demonstrated that expression of the betaproteobacterial orf4 and orf5 gene tandems is significantly up-regulated during recovery from ammonia starvation (5). Interestingly, all orf4-orf5 gene tandems are flanked downstream by copper resistance genes (copCD) in the genome sequences of beta-AOB (2). Furthermore, our database search revealed that homologues of amoD (but not orf4) genes also reside in the vicinity of genes encoding copper enzymes in some genomes of MOB. In alpha-MOB, amoD homologues reside downstream of pmo genes (CAJ01564 to CAJ01562 and AAF37892 to AAF37894), which encode a homologue of AMO (1, 20). In gamma-MOB, an amoD homologue was found adjacent to genes encoding multicopper oxidases (MCA2129 and MCA2128) that are homologues of the copper oxidase gene copA upstream of the amoRCABD operon in N. oceani. Additionally, an amoD homologue, which had been missed in the annotation of the M. capsulatus genome, was identified downstream of a gene that encodes the copper resistance protein CopC (MCA2170), and both are likely coexpressed. Genes encoding proteins in the AmoD-AmoE family were found only in genomes that encode AMO or pMMO (Fig. 4).

In silico analysis of the deduced AmoD protein structure revealed that AmoD is likely exported to the periplasm but stays anchored with its C terminus in the inner membrane (19). Likewise, the AmoD protein is likely transported to and integrated into the extensive intracytoplasmic membrane system of AOB, where it may interact with electron transfer proteins and enzymes that facilitate the oxidation of ammonia or their maturation. This hypothesis is based on our findings that amoD is an expressed member of the amo operon in Nitrosococcus, that it is also expressed in beta-AOB (5), and that it is conserved in sequence and synteny in the amo gene clusters of all AOB, all of which suggests that the amo cluster genes encode proteins that interact physically (4, 11, 17).

In summary, we hypothesize that the amoD gene is distributed in AOB and MOB similar to other inventory that is involved in nitrification (i.e., amo [pmo] and hao [2, 4, 16]) and that AmoD is unique to organisms capable of ammonia oxidation and nitrification. Because the amoD gene is ancestral to orf4 (Fig. 4), which has likely arisen by complete gene duplication from amoD in the ancestor of all beta-AOB, we propose naming the orf4 gene of beta-AOB “amoE.” By analogy to amoC and pmoC, we propose naming all amoD-homologous singleton genes identified in AOB and MOB “amoD” and “pmoD,” respectively.

Conclusions.

We have discovered that the amo gene cluster in N. oceani consists of five genes instead of the three known genes, amoCAB, and introduced the genes amoR and amoD. The transcription of the five genes in the amoRCABD gene cluster is not equal because other promoters in this cluster have been formerly identified in AOB (1, 14, 20, 21), and leaky terminators downstream of amoC (21) and amoB (this study) halt some but not all RNA polymerases that transcribe the genes in this cluster. We have shown that expression from a promoter at least 600 bp upstream of amoC generates an amoRCABD transcript in N. oceani and that these five genes constitute an operon when expressed under normal growth conditions. The unique presence of AmoR and absence of AmoE in Nitrosococcus (this study) and the significant difference in amo operon copy number as well as the difference in organization of transcriptional units between Nitrosococcus and beta-AOB (2, 3, 5, 6; this study) suggest that the transcription of ammonia-catabolic genes is differently regulated in beta-AOB and Nitrosococcus. Putative functions of the AmoR and AmoD proteins have been proposed, but future studies at the protein level are needed to determine their roles in the process of ammonia oxidation by Nitrosococcus.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. J. Schultz (University of Louisville) for valuable advice on the RNA manipulations and L. Y. Stein (University of California, Riverside) and three anonymous reviewers for critical reading of the manuscript.

This project was supported, in part, by incentive funds provided by the University of Louisville-EVPR office, the KY Science and Engineering Foundation (KSEF-787-RDE-007), and the National Science Foundation (EF-0412129).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzerreca, J. J., J. M. Norton, and M. G. Klotz. 1999. The amo operon in marine, ammonia-oxidizing Gammaproteobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 180:21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arp, D. J., P. S. G. Chain, and M. G. Klotz. 2007. The impact of genome analyses on our understanding of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:21-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arp, D. J., L. A. Sayavedra-Soto, and N. G. Hommes. 2002. Molecular biology and biochemistry of ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas europaea. Arch. Microbiol. 178:250-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergmann, D. J., A. B. Hooper, and M. G. Klotz. 2005. Structure and sequence conservation of genes in the hao cluster of autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: evidence for their evolutionary history. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5371-5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berube, P. M., S. C. Proll, and D. A. Stahl. 2007. Genome wide transcriptional analysis following the recovery of Nitrosomonas europaea from ammonia starvation, abstr. H-105. Abstr. 107th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.

- 6.Berube, P. M., R. Samudrala, and D. A. Stahl. 2007. Transcription of all amoC copies is associated with recovery of Nitrosomonas europaea from ammonia starvation. J. Bacteriol. 189:3935-3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryson, K., L. J. McGuffin, R. L. Marsden, J. J. Ward, J. S. Sodhi, and D. T. Jones. 2005. Protein structure prediction servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W36-W38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chain, P., J. Lamerdin, F. Larimer, W. Regala, V. Lao, M. Land, L. Hauser, A. Hooper, M. Klotz, J. Norton, L. Sayavedra-Soto, D. Arciero, N. Hommes, M. Whittaker, and D. Arp. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium and obligate chemolithoautotroph Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Bacteriol. 185:2759-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estrem, S. T., W. Ross, T. Gaal, Z. W. S. Chen, W. Niu, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 1999. Bacterial promoter architecture: subsite structure of UP elements and interactions with the carboxy-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit. Genes Dev. 13:2134-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooper, A. B., D. M. Arciero, D. Bergmann, and M. P. Hendrich. 2005. The oxidation of ammonia as an energy source in bacteria in respiration, p. 121-147. In D. Zannoni (ed.), Respiration in archaea and bacteria: diversity of procaryotic respiratory systems, vol. 2. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huynen, M. A., and P. Bork. 1998. Measuring genome evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5849-5856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IMG. 2006. Nitrosospira multiformis ATCC 25196. DOE Joint Genome Institute. http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/pub/main.cgi?section=TaxonDetail&page=taxonDetail&taxon_oid=637000197.

- 13.Kall, L., A. Krogh, and E. L. L. Sonnhammer. 2004. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J. Mol. Biol. 338:1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klotz, M. G., J. Alzerreca, and J. M. Norton. 1997. A gene encoding a membrane protein exists upstream of the amoA/amoB genes in ammonia oxidizing bacteria: a third member of the amo operon? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 150:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klotz, M. G., D. J. Arp, P. S. G. Chain, A. F. El-Sheikh, L. J. Hauser, N. G. Hommes, F. W. Larimer, S. A. Malfatti, J. M. Norton, A. T. Poret-Peterson, L. M. Vergez, and B. B. Ward. 2006. Complete genome sequence of the marine, chemolithoautotrophic, ammonia-oxidizing bacterium Nitrosococcus oceani ATCC 19707. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6299-6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klotz, M. G., and L. Y. Stein. 20 November 2007, posting date. Nitrifier genomics and evolution of the N-cycle. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lathe, I., Warren, C., B. Snel, and P. Bork. 2000. Gene context conservation of a higher order than operons. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray, R. G. E., and S. W. Watson. 1962. Structure of Nitrocystis oceanus and comparison with Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter. J. Bacteriol. 89:1594-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakai, K., and M. Kanehisa. 1991. Expert system for predicting protein localization sites in Gram-negative bacteria. Proteins 11:95-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norton, J. M., J. J. Alzerreca, Y. Suwa, and M. G. Klotz. 2002. Diversity of ammonia monooxygenase operon in autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 177:139-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayavedra-Soto, L. A., N. G. Hommes, J. J. Alzerreca, D. J. Arp, J. M. Norton, and M. G. Klotz. 1998. Transcription of the amoC, amoA and amoB genes in Nitrosomonas europaea and Nitrosospira sp. NpAV. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 167:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein, L. Y., D. J. Arp, P. M. Berube, P. S. G. Chain, L. J. Hauser, M. S. M. Jetten, M. G. Klotz, F. W. Larimer, J. M. Norton, H. J. M. Op den Camp, M. Shin, and X. Wei. 2007. Whole-genome analysis of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium, Nitrosomonas eutropha C91: implications for niche adaptation. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2993-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swofford, D. L. 1999. PAUP (phylogenetic analysis using parsimony), vol. 4.0.b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- 24.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The ClustalX Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson, S. 1965. Characteristics of a marine nitrifying bacterium, Nitrosocystis oceanus sp. n. Limnol. Oceanogr. 10:R274-R289. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whelan, S., and N. Goldman. 2001. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18:691-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]