Abstract

Lactococcus lactis F10, isolated from freshwater catfish, produces a bacteriocin (BacF) active against Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus carnosus, Lactobacillus curvatus, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Lactobacillus reuteri. The operon encoding BacF is located on a plasmid. Sequencing of the structural gene revealed no homology to other nisin genes. Nisin F is described.

Lantibiotics are small, ribosomally synthesized peptides with lanthionine rings and dehydrated amino acid residues. Nisin A was isolated from a strain of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis by Mattick and Hirsch (14), and the structure was published by Gross and Morell (10). Since then, a number of lantibiotics have been described, mostly from Lactococcus lactis and Streptococcus, Bacillus, Staphylococcus, and Streptomyces spp. (6).

The nisin A operon has been studied in detail and consists of 11 genes, i.e., nisA, nisB, nisT, nisC, nisI, nisP, nisR, nisK, nisF, nisE, and nisG. The prepeptide is encoded by the structural gene nisA (2). nisB and nisC are involved in maturation of the lantibiotic, and nisT is involved in transport across the cell membrane (7). nisI encodes an immunity protein, and nisP encodes a putative serine protease involved in processing (8). nisR and nisK encode a putative regulatory protein and a putative histidine kinase, respectively (8, 20). nisF, nisE, and nisG encode ATP-binding cassette transporters that are, together with nisI, responsible for immunity (18). The bacteriocin described in this paper is structurally different from nisins A, Z, Q, and U and represents a fifth variation of the lantibiotic, designated nisin F.

Lactic acid bacteria were cultured in de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth (Biolab, Biolab Diagnostics, Midrand, South Africa) at 30°C, Staphylococcus aureus was cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Biolab) at 37°C, and Escherichia coli DH5α was cultured in Luria-Bertani broth (Biolab) on a rotating wheel (model TC-7; New Brunswick Scientific Co., Inc., Edison, NJ) at 37°C. The target strains and growth conditions are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Target strains, growth conditions, and spectrum of antimicrobial activity

| Target strain(s)a | Growth medium and conditionsb | Antimicrobial activityc |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus acidophilus LMG 13550 | MRS, 37°C, anaerobic | − |

| Lactobacillus bulgaricus LMG 13551 | MRS, 37°C, anaerobic | − |

| Lactobacillus casei LMG 13552 | MRS, 37°C, anaerobic | − |

| Lactobacillus curvatus LMG 13553 | MRS, 30°C, anaerobic | ++ |

| Lactobacillus fermentum LMG 13554 | MRS, 37°C, anaerobic | − |

| Lactobacillus helveticus LMG 13555 | MRS, 42°C, anaerobic | − |

| Lactobacillus plantarum LMG 13556 | MRS, 37°C, anaerobic | ++ |

| Lactobacillus reuteri LMG 13557 | MRS, 37°C, anaerobic | + |

| Lactobacillus sakei LMG 13558 | MRS, 30°C, anaerobic | − |

| Pediococcus pentosaceus LMG 13560, LMG 13561 | MRS, 30°C, anaerobic | − |

| Leuconostoc cremoris LMG 13562, LMG 13563 | MRS, 30°C, anaerobic | − |

| Streptococcus thermophilus LMG 13564, LMG 13565 | MRS, 42°C, anaerobic | − |

| Enterococcus faecalis LMG 13566 | BHI, 37°C, anaerobic | − |

| Staphylococcus carnosus LMG 13567 | BHI, 37°C, anaerobic | +++ |

| Listeria innocua LMG 13568 | BHI, 30°C, anaerobic | − |

| Bacillus cereus LMG 13569 | BHI, 37°C anaerobic | − |

| Clostridium sporogenes LMG 13570 | RCM, 37°C, anaerobic | − |

| Clostridium tyrobutyricum LMG 13571 | RCM, 30°C, anaerobic | − |

| Propionibacterium sp. strain LMG 13574 | GYP, 32°C, anaerobic | − |

| Staphylococcus aureus K (our collection) | BHI, 37°C, aerobic | +++ |

| Staphylococcus aureus J (our collection) | BHI, 37°C, aerobic | +++ |

LMG, strains received from the Laboratorium voor Microbiologie, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium, now deposited into the Belgian Co-ordinated Collection of Micro-organisms (BCCM)/LMG Culture Collection (http://bccm.belspo.be/about/lmg.php).

RCM, reinforced clostridium medium; GYP, glucose-yeast-peptone.

−, no inhibition; +, ++, and +++, inhibition zones of 2 to 4, 4 to 8, and >8 mm in diameter, respectively.

Feces collected from the intestinal tract of Clarias gariepinus, a freshwater fish from a river in Stellenbosch, South Africa, were inoculated into MRS broth and incubated for 24 h at 30°C. Cultures were streaked onto MRS agar (Biolab) plates and incubated for 24 h at 30°C. Plates with fewer than 50 colonies were overlaid with BHI soft agar, each containing a pure culture of S. aureus. Colonies of lactic acid bacteria with the largest inhibition zones were selected and purified by streaking the bacteria onto MRS agar. The presence of antimicrobial compounds in cell-free culture supernatants was confirmed by using the agar spot method (12).

The strain that showed the best antimicrobial activity was selected and identified according to sugar fermentation reactions (API 50 CHL; bioMérieux, France), key differential characteristics (11), and 16S rRNA gene sequencing (9).

Bacteriocin F was semipurified by ammonium sulfate precipitation and dialysis according to the method described by Sambrook et al. (16). The stability of the semipurified bacteriocin against different enzymes, temperatures, and pH levels was tested according to the method of Todorov and Dicks (19). The activity of the samples was tested by using the agar spot method (12). The antimicrobial activity of the crude bacteriocin was tested against S. aureus and strains from the Laboratorium voor Microbiologie (LMG) panel (Table 1). Each strain (1 × 106 CFU) was embedded in soft agar and the activity of nisin was tested as described before. The approximate molecular size of the BacF was determined by Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (17), as described by van Reenen et al. (21). S. aureus K (106 CFU ml−1) was used as a sensitive strain.

Strain F10 was cured according to the method of De Kwaadsteniet et al. (4) and was modified by supplementing MRS broth with 20 to 80 μg ml−1 ethidium bromide (Sigma) instead of novobiocin or SDS.

Genomic and plasmid DNA of strain F10 was isolated according to the method described by Dellaglio et al. (5) and by using a plasmid midi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), respectively. The size of the plasmid was determined from fragments generated by digestion with AccI (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Germany), as described by Sambrook et al. (16).

Genomic and plasmid DNA was amplified with primers designed from the structural gene of nisin Q (GenBank accession number AB100029). The following primers were used: nisin forward primer (nisF), 5′-ATGAGTACAAAAGATTTCAACTT-3′, and nisin reverse primer (nisR), 5′-TTATTTGCTTACGTGAACGC-3′. The amplification conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 94°C for 4 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 48°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 7 s; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were cleaned with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and sequenced with an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (PE Biosystems SA). The exact molecular size of mature BacF (without the leader peptide) was determined from the amino acid sequence deduced from the DNA sequence. DNA homology to sequences listed in GenBank was determined using the BLAST program (1).

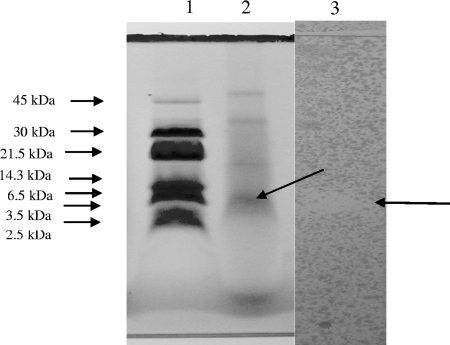

Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene PCR product revealed 99% homology between strain F10, Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IL-1403, and L. lactis strain KLDS 4.0319. Strain F10 is thus classified as L. lactis subsp. lactis. BacF inhibited the growth of two strains of S. aureus that have been isolated from patients diagnosed with sinusitis, Lactobacillus curvatus LMG 13553, Lactobacillus plantarum LMG 13556, Lactobacillus reuteri LMG 13557, and Staphylococcus carnosus LMG 13567 (Table 1). Antimicrobial activity was lost after treatment with pronase, confirming that activity was conferred by a peptide. The bacteriocin remained active after treatment with amylase, pepsin, and proteinase K. Levels of antimicrobial activity remained unchanged after 100 min at 90°C, but activity was lost after autoclaving. Activity was recorded over a broad pH range (from pH 2 to 10). According to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the bacteriocin is between 6.5 and 14.3 kDa in size (Fig. 1). The size and the isoelectric point of the mature peptide (without the leader peptide) are 3,457 kDa and 8.73, respectively, as deduced from the DNA sequence of the structural gene encoding the mature peptide.

FIG. 1.

Separation of partially purified nisin F by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Lane 1, rainbow low-range protein size marker RPN755 (Amersham International, United Kingdom); lane 2, protein band representing nisin F (arrow); lane 3, inhibition of S. aureus K (arrow), embedded in BHI soft agar (1%).

As far as we could determine, this is the second report of bacteriocin-producing strains of L. lactis isolated from fresh fish. The paper by Campos and coworkers (3) described strains of L. lactis with activity against Listeria monocytogenes and S. aureus, but it did not characterize the bacteriocins.

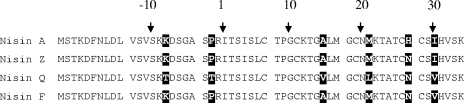

L. lactis F10 harbors a plasmid of approximately 24 kb. Strain F10 lost the ability to produce bacteriocin F after growth in the presence of ethidium bromide (30 μg ml−1), suggesting that the genes encoding the bacteriocin are located on the plasmid. The DNA primers that we have designed differ by one or two bases from the structural genes of nisin A, nisin Z, and nisin U (data not shown). The sequence of the DNA fragment amplified from strain F10 (GenBank accession number EU057979) is similar to the sequence recorded for the structural gene encoding nisin Z (GenBank accession number X61144) (15), except for valine instead of isoleucine at position 30. Homology was also recorded with nisin Q (GenBank accession number AB100029), also having valine at position 30 (Fig. 2). However, BacF differs from nisin Q by having alanine and not valine at position 15 and methionine instead of leucine at position 21. It is interesting to note that nisin Q was also isolated from a river in Japan (22). Bacteriocin F is thus regarded as a new variety of nisin and is named nisin F.

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequences of nisin F, deduced from the DNA sequence (GenBank accession number EU057979) and compared to the amino acid sequences of nisin A, nisin Z, and nisin Q. The leader peptide of each nisin variant consists of 13 amino acids (from position −13 to −1), followed by amino acids encoding the mature protein (amino acid positions 1 to 34). Differences in amino acids are indicated by letters with a black background.

Nisin F proved very effective against clinical strains of S. aureus and may be used to prevent sinusitis. We are at present conducting research on Wistar rats to test this hypothesis. In previous studies, the lantibiotic mersacidin has been used to eradicate S. aureus from the respiratory tract of mice (13).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation (NRF), South Africa.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchman, G. W., S. Banerjee, and J. N. Hansen. 1988. Structure, expression, and evolution of a gene encoding the precursor of nisin, a small protein antibiotic. J. Biol. Chem. 263:16260-16266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campos, C. A., Ó. Rodríquez, P. Calo-Mata, M. Prado, and J. Barros-Velázquez. 2006. Preliminary characterization of bacteriocins from Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus mundtii strains isolated from turbot (Psetta maxima). Food Res. Int. 39:356-364. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Kwaadsteniet, M., T. Fraser, C. A. Van Reenen, and L. M. T. Dicks. 2006. Bacteriocin T8, a novel class IIa sec-dependent bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus faecium T8, isolated from vaginal secretions of children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4761-4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellaglio, F. V., V. Bottazzi, and L. D. Trovatelli. 1973. Deoxyribonucleic acid homology and base composition in some thermophilic lactobacilli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 74:289-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Vuyst, L., and E. J. Vandamme (ed.). 1994. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria: microbiology, genetics and application. Blackie Academic & Professional, Chapman & Hall, London, England.

- 7.Engelke, G., Z. Gutowski-Eckel, M. Hammelmann, and K.-D. Entian. 1992. Biosynthesis of the lantibiotic nisin: genomic organization and membrane localization of the NisB protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3730-3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelke, G., Z. Gutowski-Eckel, P. Kiesau, K. Siegers, M. Hammelmann, and K.-D. Entian. 1994. Regulation of nisin biosynthesis and immunity in Lactococcus lactis 6F3. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:814-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felske, A., H. Rheims, A. Wolterink, E. Stackebrandt, and A. D. L. Akkermans. 1997. Ribosome analysis reveals prominent activity of an uncultured member of the class Actinobacteria in grassland soils. Microbiology 143:2983-2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross, E., and J. L. Morell. 1971. The structure of nisin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93:4634-4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt, J. G. (ed.). 1994. Bergey's manual of determinative bacteriology. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD.

- 12.Ivanova, I., V. Miteva, T. Stefanova, A. Pantev, I. Budakov, S. Danova, P. Moncheva, I. Nikolova, X. Dousset, and P. Boyaval. 1998. Characterization of a bacteriocin produced by Streptococcus thermophilus 81. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 42:147-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruszewska, D., H. G. Sahl, G. Bierbaum, U. Pag, S. O. Hynes, and A. Ljungh. 2004. Mersacidin eradicates methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a mouse rhinitis model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:648-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattick, A. T. R., and A. Hirsch. 1947. Further observation on an inhibitory substance (nisin) from lactic streptococci. Lancet ii:5-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulders, J. W., I. J. Boerrigter, H. S. Rollema, R. J. Siezen, and W. M. de Vos. 1991. Identification and characterization of the lantibiotic nisin Z, a natural nisin variant. Eur. J. Biochem. 201:581-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 17.Schägger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein, T., S. Heinzmann, I. Solovieva, and K. D. Entian. 2003. Function of Lactococcus lactis nisin immunity genes nisI and nisFEG after coordinated expression in the surrogate host Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todorov, S. D., and L. M. T. Dicks. 2005. Characterization of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria isolated from spoiled black olives. J. Basic Microbiol. 45:312-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Meer, J. R., J. Polman, M. M. Beerthuyzen, R. J. Siezen, O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. De Vos. 1993. Characterization of the Lactococcus lactis nisin A operon genes nisP, encoding a subtilisin-like serine protease involved in precursor processing, and nisR, encoding a regulatory protein involved in nisin biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 175:2578-2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Reenen, C. A., L. M. T. Dicks, and M. L. Chikindas. 1998. Isolation, purification and partial characterization of plantaricin 423, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84:1131-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zendo, T., M. Fukao, K. Ueda, T. Higuchi, J. Nakayama, and K. Sonomoto. 2003. Identification of the lantibiotic nisin Q, a new natural nisin variant produced by Lactococcus lactis 61-14 isolated from a river in Japan. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 67:1616-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]