Abstract

R-loops have been described in vivo at the immunoglobulin class switch sequences and at prokaryotic and mitochondrial origins of replication. However, the biochemical mechanism and determinants of R-loop formation are unclear. We find that R-loop formation is nearly eliminated when RNase T1 is added during transcription but not when it is added afterward. Hence, rather than forming simply as an extension of the RNA-DNA hybrid of normal transcription, the RNA must exit the RNA polymerase and compete with the nontemplate DNA strand for an R-loop to form. R-loops persist even when transcription is done in Li+ or Cs+, which do not support G-quartet formation. Hence, R-loop formation does not rely on G-quartet formation. R-loop formation efficiency decreases as the number of switch repeats is decreased, although a very low level of R-loop formation occurs at even one 49-bp switch repeat. R-loop formation decreases sharply as G clustering is reduced, even when G density is kept constant. The critical level for R-loop formation is approximately the same point to which evolution drove the G clustering and G density on the nontemplate strand of mammalian switch regions. This provides an independent basis for concluding that the primary function of G clustering, in the context of high G density, is R-loop formation.

R-loops are nucleic acid structures in which an RNA strand displaces one strand of DNA for a limited length in an otherwise duplex DNA molecule. R-loops were named by analogy to D-loops, which is where all three strands are DNA. R-loops form in vivo at sequences that generate a G-rich transcript at the prokaryotic origins of replication (20), mitochondrial origins of replication (18), and mammalian immunoglobulin (Ig) class switch sequences (reviewed in reference 45). In addition, R-loop formation occurs in vivo at some G-rich transcript locations that are distinctly high for mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and this high recombination rate is reduced upon overexpression of S. cerevisiae RNase H1 (14). When prokaryotes lack topoisomerase activity, R-loops can form at a wider variety of sequences, and the lethality associated with this can be remedied by overexpression of Escherichia coli RNase H1 (7). In an avian lymphoid cell line, lack of the ASF2/SF2 RNA-binding protein favors R-loop formation at G-rich transcript locations in the genome, and expression of human RNase H1 can abolish the R-loop (19).

In vitro studies of R-loop formation at prokaryotic origins and Ig class switch regions have paralleled many of the observations seen in vivo. In vitro studies utilize prokaryotic RNA polymerases, often the phage T7 or T3 RNA polymerases, and purified plasmid DNA. Ig class switch recombination (CSR) sequences have been the focus of most of these in vitro studies (6, 9, 28, 29, 38), although studies on mitochondrial and prokaryotic replication origins have also been done (18, 41). The R-loops only form when in vitro transcription occurs in the direction that results in a G-rich transcript. There has been no systematic study of how G-rich or how long the regions must be, nor has there been any sequence modification to assess any aspect of these G-rich regions for their propensity to form R-loops.

Ig CSR occurs at switch regions. In mammals, recombination occurs between the Sμ region, which is located upstream of the constant exons encoding Igμ heavy chain, and any one of the downstream switch regions, Sγ, Sα, or Sɛ, which are located upstream of the constant exons encoding the Igγ, Igα, and Igɛ heavy chains, respectively (3, 5, 33, 45). In mammals, the Ig switch regions are usually several kilobases in length, G-rich on the nontemplate strand (thereby generating a G-rich RNA transcript), and repetitive (with a repeat length of between 25 and 80 bp). Many of the G's are in clusters of 2 to 5 nucleotides (nt). Promoters are present in front of each switch region, the transcripts generated from these promoters do not encode any protein (hence, the name sterile transcripts), and removal of the promoter results in the loss of switching to that specific switch region (35, 42). Ig CSR occurs in germinal-center B cells located in the peripheral lymphoid tissues (e.g., lymph nodes, Peyer's patches, and spleen) upon cytokine stimulation. Different cytokines stimulate the promoters upstream of the different switch regions (36).

Ig CSR requires a cytidine deaminase called activation-induced deaminase (AID), which is expressed in activated B cells (24). AID only deaminates C's when these are located in single-stranded DNA (4, 25, 44). CSR at the downstream switch regions occurs within the switch repetitive regions, and recombination at Sμ can sometimes occur upstream (35%) or downstream (8%) of the Sμ switch repeats (8, 21-23). Given that AID requires single-stranded DNA, a key question concerns how any single strandedness is exposed within the switch regions (33). We have shown that R-loops are detectable at the Sγ3 and Sγ2b acceptor switch regions (13, 43) and, more recently, at the Sμ switch regions (12). These R-loops can be kilobases in length and provide a ready target for AID at any of the C's within the top strand. Single strandedness on the bottom strand may derive from partial or complete action by endogenous RNase H in its removal of the RNA that is annealed to the bottom strand (43, 45). After AID action on the top and bottom strands, uracil glycosylase (UNG2) converts these to abasic sites (16, 27), and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APE1) may nick the phosphodiester backbone 5′ of the abasic site (10). Double-strand breaks could arise from nicks that are sufficiently close, or after nucleases, such as Exo 1 (1), resect from the nick toward an adjacent nick.

The mechanism of R-loop formation is of key importance not only for the immune system during CSR but also for any processes in biology where R-loops arise. Here we have focused on three central issues about the mechanism of R-loop formation. First, how does the RNA that forms the R-loop arrive at a position that permits it to reanneal with the template DNA strand? Is it simply an extension of the standard 9-bp RNA-DNA hybrid formed during transcription and known to form within all RNA polymerases? Or does it thread back to anneal with the template DNA strand after traversing the exit pore that exists in all RNA polymerases? Second, is G-quartet formation by the G-rich nontemplate strand essential for R-loop formation? Third, what is the minimum length of Ig switch region DNA necessary for R-loop formation, and can a reduction in G density or a reduction in the extent of G clustering still permit R-loop formation?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid switch substrates.

All of the Ig class switch region sequences used in the present study are from the murine Sγ3 region. The wild-type switch sequences in pDR3 include 4 of the 41 repeats from the murine Sγ3 region. These four are repeat numbers 13, 14, 15, and 16 (37), and they were introduced using oligonucleotides and PCR into pKY127. pKY127 is simply a derivative of pBKS(+) with a deletion of the lacZ promoter and replacement with an oligonucleotide that serves as a multipurpose cloning region.

pTW122 (also called pTW-EL91) contains 5.5 repeats and is the same as pTW-SS91 (43) except for minor differences in the multipurpose cloning region. Another four-repeat substrate (pDR18), pDR49 (one repeat), pDR50 (two repeats), pDR51 (three repeats), and substrates containing four modified repeats, pDR22, pDR26, and pDR30, used in our studies, were also made similarly as described above for pDR3. In pDR22, G clusters containing four or five G's in the wild-type sequence were reduced to clusters of three G's, whereas pDR26 was made with four repeats in which all clusters of three, four, or five G's were made to clusters of two G's, while pDR30 has the four Sγ3 repeats where all clusters of five, four, three, and two G's were disrupted such as no two G's could be adjacent to each other. A transcription substrate called pDR54 was constructed to have 49.7% G density on the nontemplate strand such that every alternate nucleotide is a G. This substrate was constructed to compare the effect of G density on R-loop formation and was made by using a 189-bp XhoI-digested PCR fragment that was cloned so that transcription from the T7 promoter generates a G-rich RNA.

The plasmid DNA was extracted from bacterial cultures of transformed bacterial colonies and purified on CsCl gradients, followed by ethanol precipitation using standard procedures. For the G-quartet experiments, pTW122 was purified by using a CsCl gradient, followed by precipitation and reprecipitation without monovalent salt but with glycogen to preclude introduction of other monovalent cations into the DNA preparation. An ethanol rinse was then done (with no added salt), followed by resuspension in the transcription buffer with the specified cation. Hence, any G quartets formed during transcription would need to form in the presence of the specified cation. In the experiments where this template is linearized, the restriction digestion was done using in a Na+-free buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 10 mM MgCl2.

DR050 and DR051 or DR056 were used for PCR, while DR075, DR076, or DR110 were used as probes to detect bisulfite converted R-loop derivative molecules in the colony lift hybridization assay.

For the sequences of the oligonucleotides and other related information about enzymes, reagents, and the construction of the plasmids, see the supplemental material.

In vitro transcription of switch substrates.

Supercoiled or linearized (restriction enzyme-digested) switch DNA substrates were transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) in the physiological orientation at 37°C for 1 h in accordance with the polymerase manufacturer's instructions. Radiolabeled [α-32P]UTP was added to the reaction wherever specified. For the RNase T1 experiment, 1 μg of RNase A or 100 U of RNase T1 was added (per μg of DNA transcribed) during the transcription or after heat inactivation of the reaction at 65°C for 20 min. Then, 50 ng of purified E. coli RNase H1 was added per μg of DNA transcribed where specified. Unless otherwise specified, RNase H1 and/or RNase A were added after the transcription reaction, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h. For the G-quartet test, pTW122 was digested in Na+-free buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 10 mM MgCl2, and transcription was done in buffers that had the same composition as the commercially available buffer from Promega except that the Na+ was replaced with Li+, K+, or Cs+. The transcribed DNA was electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and poststained with ethidium bromide. Radiolabeled species were detected by exposing the gels to phosphorimager screens and scanning them on a Molecular Dynamics Imager 445SI (Sunnyvale, CA). Bands were analyzed with ImageQuant software version 5.0.

Determination of frequency of R-loop formation.

Portions (2 μg) of SalI-digested plasmid switch substrates were transcribed, treated with RNase A, organically extracted, and precipitated with ethanol. Sodium bisulfite treatment was done as described previously (43). PCR amplification on bisulfite-modified DNA was done with DR050 and DR051 or DR056 (all native primers). The PCR fragment was cloned with a TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Bacterial colonies were lifted onto nylon membranes (13) and probed with oligonucleotides designed to anneal to a region containing C-to-T conversions but not to an unconverted region on the nontemplate strand. Each probe was designed to bind with a region with approximately six C-to-T changes over a length of approximately 25 bp. Oligonucleotide probes DR075 (for pDR18, pDR26, pDR49, pDR50, and pDR51), DR076 (for pDR26), and DR110 (for pDR54) were radiolabeled in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and used for the detection of putative clones with regions containing C-to-T converted sites. The C-to-T conversions found in the region between DR050 and DR051 are shown in appropriate figures. Molecules with ≥25-nt stretches containing at least three consecutive C-to-T conversions were considered to be regions of single strandedness.

Enrichment of R-loops by cutting the RNA-DNA hybrid bands from an agarose gel.

To study the nature of shifted DNA species, we ran 2 μg of restriction-digested and T7-transcribed, RNase A-treated DNA on 0.8% low-melting-temperature agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA and cut out the shifted fragment seen on the gel or the corresponding position where a shift is expected (marginally above the DNA band containing the switch region). This gel slice was incubated with sodium bisulfite and analyzed further by sequencing.

RESULTS

Experimental strategy.

The normal mammalian switch regions are kilobases in length. For example, the murine Sγ3 switch region consists of 41 consecutive head-to-tail copies of an ∼49-bp repeat. We have shown previously that shorter forms of Sγ3 can still support R-loop formation on supercoiled plasmids very efficiently in vitro (43, 46). Supercoiled plasmids form R-loops particularly efficiently because the inherent negative supercoiling favors strand separation. We wanted to eliminate any contribution of negative supercoiling, and thus we have used linear DNA substrates here except where specified; this provides a more stringent test of R-loop formation. Moreover, DNA in the genome, while somewhat negatively supercoiled (17), is unlikely to be as negatively supercoiled as prokaryotic plasmids.

For the studies here, we use prokaryotic RNA polymerases, typically T7 RNA polymerase, and we transcribe for 1 h of incubation at 37°C. The samples are organically extracted, ethanol precipitated, resuspended, and then run on agarose gels. Where indicated, the transcription is done using radiolabeled [α-32P]UTP. The fraction of substrate that forms an R-loop exhibits a mobility difference and runs more slowly than the double-stranded DNA substrate, even on these linear substrates (7). We and others have demonstrated that the DNA in the shifted position is R-looped, based on RNase H1 sensitivity and sodium bisulfite chemical probing for single strandedness (12, 31, 43).

Test of a thread-back model for R-loop formation.

We were interested in how the RNA comes to be annealed to the template DNA strand, and there are two major pathways that one can consider (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). All RNA polymerases (prokaryotic and eukaryotic) have exit channels where the nascent RNA normally exits. One possibility is that the RNA comes out of the exit pore of the RNA polymerase and then anneals to the template strand before the two DNA strands anneal to one another. Once an initial RNA-DNA association is formed between the G-rich RNA and the template DNA, the rest of the RNA can thread back and form an RNA-DNA hybrid, which is thermodynamically more stable than the double-stranded B-DNA (30). This model of R-loop formation can be termed RNA “thread back” and requires that the RNA be single stranded for a short period of time before hybridizing with the template DNA strand.

A second possibility, which can be called the “extended-hybrid” model, assumes that the transcript that forms upon transcription of the switch sequences fails to denature from the template in the transcription bubble, owing to the high thermodynamic stability of the short G-rich RNA-DNA hybrid. Then, the remainder of the transcript simply extends as the RNA polymerase transcribes and moves forward on the template. If this model applies, then there would be no free-RNA phase, and the RNA would be annealed to the template strand the entire time.

To distinguish between the two models and dissect the mechanism of RNA association with the DNA, we added RNase T1 during the transcription of linearized switch substrates containing four wild type, murine Sγ3 (switch region) repeats (diagrammed in Fig. 1C). If the nascent RNA is exposed at any time, the RNase T1, which nicks 3′ of the G's, will suppress R-loop formation (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). For the present study, RNase T1 is superior to RNase A, which cuts only after pyrimidines, because the RNA strand is relatively poor in pyrimidines and may be cut less frequently than with RNase T1.

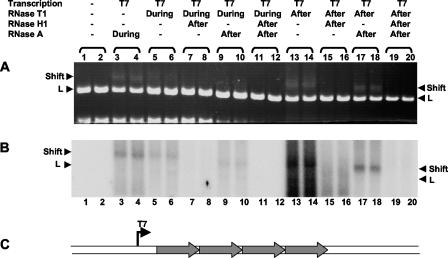

FIG. 1.

RNase T1 interferes with R-loop formation on a linearized switch substrate containing four repeats of murine Sγ3. The substrate, pDR3, was linearized with ApaL1 and then transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of [α-32P]UTP. RNase T1 was added during or after the transcription incubation to test whether it can interfere with the mobility shift (labeled Shift) caused by R-loop formation. RNase A was added where indicated after transcription to digest excess RNA, which would otherwise interfere with visualization of other species in the lane. The lanes were run in duplicate, as indicated by the brackets above the lane numbers. A reduction in the amount of shift is observed when RNase T1 is present during the transcription (lanes 9 and 10) compared to when it is added after transcription (lanes 17 and 18). RNase T1 is more effective in interfering with R-loop formation than RNase A (compare lanes 5 and 6 to lanes 3 and 4). Comparison of lanes 13 and 14 to lanes 17 and 18 demonstrates the effect of RNase A added after transcription. RNase H1 was added where noted to show the reversal of the mobility shift (lanes 7 and 8, lanes 11 and 12, lanes 15 and 16, and lanes 19 and 20). No shift is seen when the DNA is not transcribed (lanes 1 and 2). (A) The ethidium bromide-stained gel demonstrates both the shifted DNA (positions labeled Shift) and the linear fragment that contains the switch sequence (position labeled L). An irrelevant restriction fragment from the plasmid runs at or near the bottom of the gel. (B) The radioactive profile of the gel in panel A is shown. Only the shifted DNA, but not the linearized DNA (L), becomes radioactively labeled, indicating the presence of RNA in the shifted species. (C) A schematic of the linearized substrate containing the four repeats of murine Sγ3 is shown. Shaded arrows indicate the four switch repeats. The T7 promoter is shown with a thin solid arrow above the line.

We transcribed 200 ng of linearized switch substrate with T7 RNA polymerase with or without 20 U of RNase T1. Where it is specified, RNase A was added after the transcription in order to destroy free RNA that would otherwise obscure gel analysis. The gels show the shifted species associated with R-loop formation when RNase T1 and RNase A were both added after the transcription step (Fig. 1A, lanes 17 and 18). Importantly, the shifted species was markedly reduced if the same amount of RNase T1 was present during the transcription step, and the RNase A was still added afterward (Fig. 1A, lanes 9 and 10). As a secondary point, when RNase A is present during transcription (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 4), it does not reduce the R-loop shifted species nearly as much as RNase T1 (lanes 5 and 6). As mentioned earlier, this is because the number of cut sites in the nascent RNA for RNase A is much smaller than for RNase T1.

Because the transcription was done with radiolabeled [α-32P]UTP, gel exposure provides information about the location of the RNA on the gel. The radiolabeled RNA is associated in mobility with the linear DNA fragment (Fig. 1B, lanes 17 and 18), and this RNA is not visible in the lanes where RNase T1 is present during transcription (Fig. 1B, lanes 9 and 10). Note that when RNase A is not used at any time in the experiment, then the lanes are obscured by the radiolabeled RNA (lanes 13 and 14).

Therefore, the nascent RNA is vulnerable to single-strand-specific RNases, such as RNase T1, when there are sufficient cut sites at which these can act. This finding is inconsistent with the extended-hybrid model and is quite consistent with the thread-back model (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material).

Test of G-quartet formation at Ig class sequence R-loops.

As mentioned above, class switch sequences are repetitive in nature and are extremely rich in G nucleotides on the nontemplate strand (49% G for the mouse Sγ3 nontemplate strand). In addition, the G nucleotides in the switch regions tend to occur in clusters of three, four, or five G's, making G quartets a possibility (6, 9). Such structures have been proposed to exist at other G-rich sites in the genome, and this raises the possibility that the R-loops found at the switch sequences are dependent upon G-quartet formation at the G-rich nontemplate DNA strand. G quartets have very specific dimensions and are stabilized by K+ or Na+ cations, which have the right size for the cavity in the center of a G quartet or between planes of more than one G quartet. G quartets are destabilized in presence of Cs+, which is too large, or by Li+, which is too small (32).

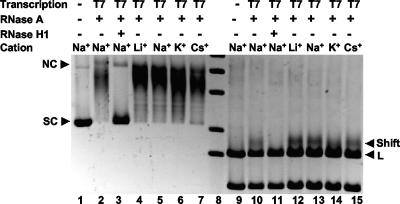

We wondered whether R-loops are formed as a result of G-quartet formation on the nontemplate DNA strand. If this were true, then the presence of inhibitory cations that inhibit G-quartet formation would also suppress R-looping. To test this, we prepared DNA templates in a manner such that only one type of monovalent cation was present (see Materials and Methods). We transcribed a minimal switch substrate containing 5.5 repeats of murine Sγ3, either in supercoiled or in linearized form, with T7 RNA polymerase with only Li+, Na+, K+, or Cs+ present in the transcription buffer as the monovalent cation. Hence, if G quartets were to form during the transcription, then they would have to do so in the presence of only these specified cations. We then ran the samples on a gel to assess the transcription-induced mobility-shifted species. We found that in Li+ (Fig. 2, lane 4 for supercoiled substrate and lane 12 for linearized substrate) or in Cs+ (Fig. 2, lane 7 for supercoiled substrate and lane 15 for linearized substrate) the R-loop-induced shift persists (Fig. 2, lanes 5 and 6 for supercoiled and lanes 13 and 14 for linearized substrate). Based on this, R-loop formation does not require G-quartet formation. Moreover, the amount of R-loop formation is similar or higher for all of our buffers containing Li+, Na+, K+, or Cs+ (Fig. 2, lanes 4 to 7 and lanes 12 to 15 and data not shown) relative to the manufacturer's buffer for T7 RNA polymerase (Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 10), which is prepared using Na+ (and has the same composition as our Na+-based transcription buffer). Therefore, the stability of R-loops appears very unlikely to be reliant on G-quartet formation.

FIG. 2.

R-loop formation at the murine Sγ3 is not reliant on G-quartet formation. In vitro transcription was directed from the T7 promoter on supercoiled (lanes 2 to 7) or ApaL1-linearized (lanes 9 to 15) pTW122, which contains 5.5-repeat switch repeats from 13 to 17.5 of Sγ3. The transcription was done in either Promega transcription buffer (lanes 2, 3, 10, and 11) or in transcription buffers containing Li+ (lanes 4 and 12), Na+ (lanes 5 and 13), K+ (lanes 6 and 14), or Cs+ (lanes 7 or 15). Both sets of DNA (supercoiled and linearized) exhibit mobility shifts. The supercoiled (SC) DNA shifts to the nicked circular (NC) position. The linear DNA fragment shifts only slightly (labeled Shift). R-loop formation is not affected despite the presence of G-quartet destabilizing cations such as Li+ (lanes 4 and 12) or Cs+ (lanes 7 and 12) compared to Na+ (lanes 5 and 13) or K+ (lanes 6 and 14). Lanes 1 and 9 are untranscribed DNA and do not show any shift; lanes 2 and 10 are transcription reactions done in the manufacturer's buffer, and lanes 3 and 11 are transcribed DNA treated with RNase H1 to demonstrate reversal of the shift. Lane 8 is an 1-kb DNA molecular weight marker.

Determination of the minimum length of Ig switch sequences for R-loop formation.

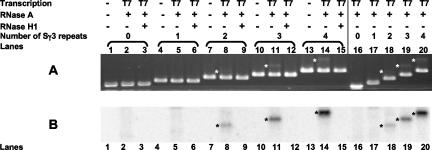

Genomic loci of mammalian class switch sequences are extremely repetitive and are known to exceed several kilobase pairs in length. While a greater length may allow for a better regional specification and targeting of the switch sequences by the class switch machinery, we wanted to know whether a smaller number of switch repeats can form R-loops and the minimal length necessary. We cloned different lengths of murine Sγ3 repeats containing one to four repeats downstream of the T7 promoter in the physiological orientation so that transcription generates a G-rich transcript. If the 41 murine Sγ3 repeats are assigned numbers 1 through 41, then pDR18 contains repeats 13 through 16 (8, 26). pDR49 contains one repeat (repeat 13), pDR50 contains two repeats (repeats 13 and 14), pDR51 contains three repeats (repeats 13 to 15), and pDR16 does not contain any switch DNA and is used as a “no-switch” DNA control. Transcription reactions were done by using linearized substrates in the presence of radiolabeled UTP (as described in Materials and Methods) and run on agarose gels. Agarose gel analysis shows that an RNase H1-sensitive shifted species is present for two, three, and four repeats but not for one or zero repeats (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 16, lanes 5 and 17, lanes 8 and 18, lanes 11 and 19, and lanes 14 and 20 for pDR16, pDR49, pDR50, pDR51, and pDR18, respectively). The amount of the shifted species (R-loop) is less for the two-repeat substrate (lane 18) than for the three- or four-repeat substrates (lanes 19 and 20). Therefore, R-loops can form on linear segments of DNA containing only two Sγ3 repeats.

FIG. 3.

In vitro transcription of linear substrates bearing zero, one, two, three, and four Sγ3 repeats. Transcription was done in the presence of [α-32P]UTP on a control substrate bearing no switch sequences (lanes 1, 2, and 3) or on substrates with one, two, three, or four wild-type Sγ3 repeats (lanes 4 to 6, 7 to 9, 10 to 12, and 13 to 15, respectively). The first lane in each set of three lanes is a mock transcription reaction without any T7 polymerase. The second lane in each set of three lanes is transcribed DNA, followed by RNase A treatment. The third lane in each set of three lanes shows the result of transcription followed by RNase A and RNase H1 treatment. The shifted bands have been highlighted with an asterisk placed on the left side of the shifted band. Duplicate reactions of transcribed and RNase A-treated DNA were run together in lanes 16 to 20 to allow for better comparison of shifted species. (A) The ethidium bromide-stained gel is shown. (B) The radiolabeled RNA of the R-loop has the same mobility (based on measurement) as the shifted band on the same gel visualized using ethidium bromide. The band for the substrate is not radiolabeled.

Quantitation of the efficiency of R-loop formation as a function of the number of switch repeat units.

To assess the length, map the location, and determine the frequency of R-loops formed at these transcribed substrates, we adapted a colony lift hybridization assay (13). In this approach, we treated the linearized and transcribed substrates containing one, two, three, or four repeats (pDR49, pDR50, pDR51, and pDR18, respectively) with sodium bisulfite and then cloned individual molecules after PCR. The PCR amplification used native unconverted DNA primers located at least 100 bp away from the beginning and end of the switch sequences.

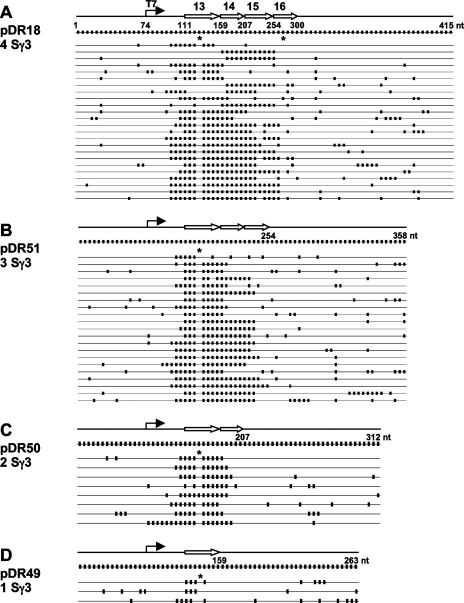

We found that R-loops are present for the one-, two-, three-, and four-repeat-containing substrates (Table 1). As expected from the agarose gel and radiolabeling data (Fig. 3), the order of efficiency of R-loop formation is highest for pDR18, containing four repeats (6.7%), and decreases to 5% for three repeats, 1% for two repeats, and 0.37% for one repeat (Table 1 and see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The colony lift hybridization assay for the detection of the R-loops appears to be more sensitive than the gel shift assay, which did not show any detectable R-loop formation for the one-repeat substrate (Fig. 3).

TABLE 1.

Frequency of R-loop formation at switch substrates containing various repeat lengths of Sγ3 as determined by the colony lift hybridization assay and sequence analysisa

| Substrate (no. of Sγ3 repeats) | Length of switch region (bp) | No. of molecules

|

Frequency of R-loop formation (% of molecules in R-looped conformation) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested in colony lift hybridization assay (nontemplate strands only) | With long stretches of single strandedness on nontemplate strand | |||

| pDR18 (4) | 189 | 362 | 24 | 6.7 |

| pDR51 (3) | 143 | 423 | 21 | 5.0 |

| pDR50 (2) | 96 | 793 | 8 | 1.0 |

| pDR49 (1) | 48 | 818 | 3 | 0.37 |

These data correspond to those in Fig. 4.

The locations of the R-loops within the one-, two-, three-, or four-repeat units is noteworthy (Fig. 4). The R-loops are nearly entirely contained within the switch repeat zones. In many instances, there is a very small amount of branch migration extending 7 nt toward the promoter but still within the transcribed region (Fig. 4). Interestingly, all of the R-loops terminated within the switch repeats. The lack of extension downstream of the repeats contrasts with R-loops in the genome at Sμ and Sγ3, where a subset of R-loops extend downstream for hundreds of base pairs (12, 13). This difference may be a function of how quickly the G density drops after the last switch repeat. In the genome, this drop is very gradual, whereas on the substrates used here, the drop is very sharp.

FIG. 4.

Location of R-loops on transcribed substrates bearing one to four Sγ3 repeats. (A) R-loop formation on substrates with four Sγ3 switch repeats. (B) R-loop formation on substrates with three Sγ3 switch repeats. (C) R-loop formation on substrates with two Sγ3 switch repeats. (D) R-loop formation on substrates with one Sγ3 switch repeat. In each panel, the top horizontal line represents the PCR fragment between primers DR050 and DR051 and shows the location of the T7 promoter, the direction of transcription, and the location of the Sγ3 repeats and their head-to-tail arrangement (open arrows). Each repeat is drawn to scale with respect to the number of C's in this region. The next horizontal line displays every C present in the nontemplate strand of the fragment (full C display), and these have been spaced equally, regardless of the actual distance between them. Each C is depicted by a short, thick vertical line. The numbers refer to the nucleotide position along the sequence. The actual results for the C-to-T conversions in individual molecules are shown in the numerous lines below the full C display. Each long horizontal line represents the sequence from a single transformant that was picked by colony lift hybridization. All of the molecules have at least three consecutive C-to-T changes on the nontemplate strand for a length of ≥25 nt. The substrates of different lengths have been aligned on repeat number 13 (first repeat). The length of the fragment has been noted under the first horizontal lane in each panel, and the asterisks represent bacterial dcm methylation sites CC(A/T)GG, where the second C of the sequence escapes bisulfite modification when methylated. For ease of visualization, the C's have been displayed equidistant relative to one another in this and the subsequent figures.

Effect of G clustering on the efficiency of R-loop formation at Ig switch sequences.

Mammalian switch repeats are remarkably rich in clusters of three, four, or five G's together, which suggests a physiologically relevant role of G clustering at these sequences (11). Significant numbers of G clusters drive the G density to a high level also. In addition to being rich in G clusters, mouse Sγ3 is ca. 49% G on the nontemplate strand, which is much higher than the mammalian genomewide average of ∼20.5% G content.

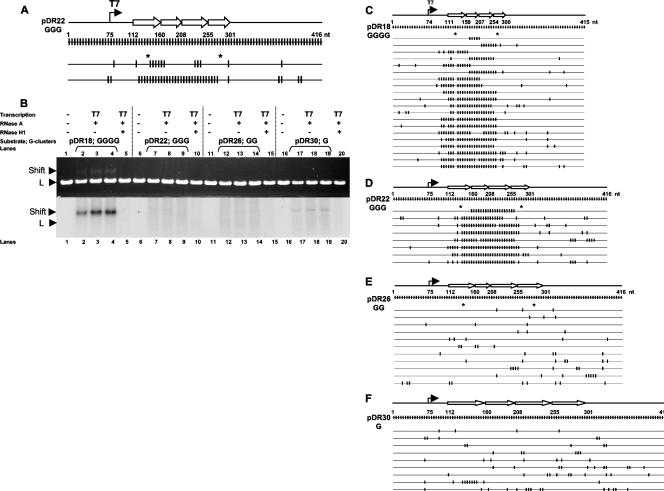

We sought to determine whether R-looping efficiency decreases with a decrease in G clustering on the nontemplate strand. To assess this, we modified the wild-type four-repeat substrate, pDR18, to make three derivative substrates in a manner that reduces the G-cluster size. For pDR22, the clusters of GGGGG were changed to cGGGc, and the clusters of GGGG were changed to GGGc. This amounts to a change of only 10 bp out of the 189-bp four-repeat switch region, and there is no change in GC density; all G changes are to C. More substantial reductions in G density and G clustering were made for pDR26 (Table 2) and pDR30 (see Materials and Methods and the methods described in the supplemental material). We then used the colony lift hybridization assay to determine the amount of R-loop formation. We found that even these minimal changes in pDR22 decrease the R-loop frequency from 6.7% to 0.23% (Table 2). The location of the R-loops is similar to that found for the wild-type four-repeat substrate (Fig. 5A). The additional decrease in pDR26 drops the frequency to an undetectable level (Table 2). Therefore, the clustering of G's is critical for R-loop formation.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of R-loop formation at four repeats of wild-type or sequence-modified Sγ3 as determined by the colony lift hybridization assay and sequence analysisa

| Substrate (length of insert [bp]) | G-cluster size (G density [%] on nontemplate strand) | No. of molecules

|

Frequency of R-loop formation (% of molecules in R-looped conformation) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested in colony lift hybridization assay (nontemplate strands only) | With long stretches of single strandedness on nontemplate strand | |||

| pDR18 (189) | GGGG (49.7) | 526 | 24 | 6.7 |

| pDR22 (189) | GGG (44.4) | 854 | 2 | 0.23 |

| pDR26 (189) | GG (41.3) | 621 | NDb | <0.16 |

| pDR54 (189) | No G clusters (49.7) | 684 | 2 | 0.29 |

FIG. 5.

Location of R-loops on transcribed substrates for which the G density of the switch repeats has been reduced. (A) The top line shows a diagram of the T7 promoter and the relative location of the four modified repeats in pDR22, where all wild-type G clusters of four or more G's were reduced to GGG. The second line shows a full display of the C's present on the nontemplate strand, with the approximate length in nucleotides depicted on the top. The third and fourth lines show the results for two R-loop molecules that were identified by colony lift hybridization assay. The asterisks note the two dcm sites present in the sequence. The first molecule has a conversion stretch of at least 35 nt, whereas the second molecule has a conversion stretch of 162 nt. (B) The substrates containing four wild-type repeats (pDR18) or four modified repeats (pDR22, pDR26, and pDR30) were either mock transcribed (lanes 1, 6, 11, and 16 for pDR18, pDR22, pDR26, and pDR30, respectively), transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of [α-32P]UTP, or treated with RNase A (second, third, and fourth lanes for each substrate; i.e., lanes 2, 3, and 4 for pDR18, lanes 7, 8, and 9 for pDR22, lanes 11, 12, and 13 for pDR26, and lanes 17, 18, and 19 for pDR30, respectively) or RNase A and RNase H1 (fifth lane for each set; i.e., lanes 5, 10, 15, and 20 for pDR18, pDR22, pDR26, and pDR30, respectively). The top gel image shows the ethidium bromide-stained gel, and the bottom image is the same gel after phosphorimager exposure. “Shift” designates the shifted species, and “L” designates the linear fragment bearing the switch sequence. Only the wild-type repeats show a shift upon transcription (bottom panel, lanes 2 to 4) but not the other three substrates. A small amount of radioactivity is seen for pDR30, but we have confirmed that this species does not form R-loops based on the bisulfite modification assay (after cutting out the region where a shift would be expected on the agarose gel and doing bisulfite sequence analysis). (C) The depiction is similar to Fig. 3. The top line shows the location and length of R-loops in the molecules derived from shift of the wild-type substrate bearing four repeats (pDR18). The second line is the full display of C's on the nontemplate strand. Asterisks are sites of the two dcm sites present in these substrates. (D) Same as panel C except for pDR22 (clusters of GGG). (E) Same as panel C except for pDR26 (clusters of GG). (F) Same as panel C except for pDR30 (isolated G's; no consecutive G's). R-loops were detected only for the wild-type repeats (C) or when the G clustering was reduced to GGG for pDR22 (shown in panel D) but not for substrates with lower G-cluster lengths (for which the conversion levels dropped to background) (shown in panels E and F). Panels C to F have all been aligned with one another at the start of the first repeat.

We were interested in evaluating a larger number of R-loops for the pDR22 substrate. After running the transcribed sequences on a gel (Fig. 5B), we cut out the shifted species and treated with bisulfite, followed by TA cloning and sequencing. The gel analysis confirmed that a reduction in G clustering reduces R-loop formation (Fig. 5B, lanes 2 to 4, in triplicate for pDR18 versus lanes 7 to 9 for pDR22, lanes 12 to 14 for pDR26, and lanes 17 to 19 for pDR30). Using this enrichment method, we still detected no R-loops when the G-cluster length was decreased to GG or G. We were able to detect R-loops for pDR22 (which has GGG clusters), and the location of the R-loops (Fig. 5C for wild-type and Fig. 5D for pDR22) was similar to those found by filter hybridization (Fig. 5A) and similar to R-loops formed on the wild-type substrate (pDR18) (Fig. 5C). Hence, small reductions in the size of G clusters result in large reductions in R-loop formation efficiency (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

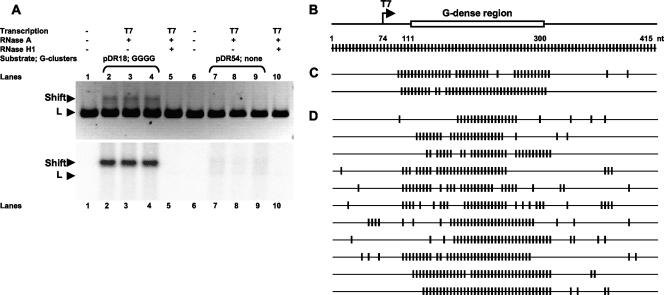

Dissection of G density from G clustering in R-loop formation efficiency.

After observing the effect of G-cluster size on R-loop formation, we sought to determine whether a complete loss of G clustering can still support R-loop formation in the context of a high G density (identical to the levels of G density on the nontemplate strand of wild-type repeats of murine switch γ3). Therefore, we constructed a transcription substrate (pDR54) identical in size and length to the four repeats contained in the wild-type substrate (pDR18) and designed it such that the substrate contains 49.7% G's over a length of 189 bp on the nontemplate strand, but with every second nucleotide being G, thereby abolishing any G clustering (no two G's next to one another). In a transcription-induced shift assay, we found that in comparison to the wild-type substrate that had a strong transcription-induced and RNase H1-sensitive gel mobility shift, this “dispersed G” substrate (pDR54) showed no notable shift (Fig. 6A), suggesting that G density alone is not sufficient for the induction of R-looping in templates with a high G density. However, in our colony lift assay, we did identify two R-looped molecules (Fig. 6C). In these two molecules, the R-loops were located in the G-dense region downstream of the promoter. The frequency of such R-looped molecules was only 0.29%, which is substantially lower than the 6.7% R-loop frequency observed for the wild-type (G-clustered) repeat substrate (pDR18). An enrichment method for detection of R-loops (as described above) allowed us to study additional molecules that were in an R-loop conformation. These experiments indicate that G clustering is the most important determinant of R-loop formation. Although R-loops can be independently supported by extremely G-dense regions, high G density is a less important determinant of R-loop formation.

FIG. 6.

Detection of transcription-induced R-loops on a substrate with high G density but no G clustering. (A) The gels show the transcription-induced gel mobilities of pDR18 (with wild-type G clusters) and pDR54 (with 49.7% G density but no G clustering). A shifted species (Shift) is seen running above the switch containing linear fragment (L) for T7 transcribed linearized pDR18 but not for pDR54 (compare triplicate lanes 2, 3, and 4 for pDR18 to lanes 7, 8, and 9 for pDR54). As expected, the untranscribed DNA (lane 1) or RNase H1-treated transcribed DNA (lane 5) do not show the shifted species for pDR18. The top panel is an image of an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. The bottom panel is the same gel as the ethidium-stained gel and shows the localization of [α-32P]UTP-labeled RNA at the shifted species for pDR18 (triplicate lanes 2, 3, and 4) but not to the linear fragment “L.” In contrast, there is almost no detectable radiolabel seen for the corresponding lanes for pDR54 (triplicate lanes 7, 8, and 9). (B) The top line depicts the PCR fragment of pDR54 with the G-dense region shown as an open rectangle and downstream of the T7 promoter. The second line depicts all of the C's on the nontemplate strand. (C) From 684 nontemplate-strand informative molecules analyzed by colony lift hybridization, only two molecules were identified as having R-loops. The R-loops are located in the G-dense region. (D) The location of R-loops in pDR54 are shown. These molecules were detected using the enrichment described in Materials and Methods. The long stretches of conversion (R-loops) are located in the G-dense region.

DISCUSSION

We found that the RNA in an R-loop is vulnerable to RNase T1 action during transcription. This observation is inconsistent with an extended-hybrid model and is most consistent with a thread-back model for R-loop formation (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). This indicates that the RNA exits the RNA polymerase exit channel and then anneals to or threads back onto the template DNA strand. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic RNA polymerases all have exit channels, and hence these findings are likely to be general ones for R-loop formation (40).

The stability of the R-loop does not require G-quartet formation (Fig. 2). Therefore, whether the nascent RNA remains unassociated with the template DNA strand versus threading back to anneal with the template strand is determined largely by the energy difference between these two states, and this is clearly a function of the DNA sequence of the region. That is, the RNA polymerase itself may have little role in determining the balance between R-loop formation and no R-loop formation. Experiments in which the species of the RNA polymerase was varied, the temperature was varied, or the ribonucleotide concentration was varied had little effect on R-loop formation (K. Yu, T. E. Wilson, G. A. Daniels, and M. R. Lieber, unpublished results). These are all factors that would influence the rate of transcription, and their lack of effect suggests that the rate of the movement of the RNA polymerase is a secondary issue for R-loop formation. In contrast, the use of ITP in place of GTP resulted in no R-loop formation (9; T. E. Wilson and M. R. Lieber, unpublished data), a finding consistent with the energy of the interaction between the RNA and DNA strands being a critical factor.

The data here support the view that clustering of G's is an important determinant of R-loop formation. In line with this, there is some propensity for the R-loops to begin at the first repeat, regardless of whether there are three or four repeats within the switch region. In particular, the R-loops frequently initiate at the GGGGTGCTGGGGTAGG sequence at the beginning of the first repeat (repeat 13) (Fig. 4 and Fig. 6A). However, this sequence alone cannot efficiently form R-loops (data not shown), and this is obvious from the inefficiency of the one-repeat substrate in forming R-loops (Table 1). Therefore, the length and the G density of the region downstream of such an R-loop initiation site probably determines the efficiency of any R-loop formation. This is further supported by our observations that R-loops located on a high-G-density substrate (but with no clusters), pDR54, are contained within the zone of high G density. Removal of G clusters dramatically decreases the efficiency of R-loop formation, even if the overall G density of the nontemplate strand is maintained. Therefore, it is quite apparent that G clusters support R-loop formation much more efficiently relative to merely a corresponding region of high G density.

The role of G clusters experimentally observed here is distinct from the conjectured role of G clusters in G-quartet formation. As we have shown above, G-quartet formation is not necessary for R-loop formation, and we have observed nothing to indicate that G quartets are forming at the R-loops in vitro or in vivo (12, 13, 43; the present study). In fact, although it occurs at low efficiency, R-loop formation does occur with the fully dispersed G-rich substrate, pDR54 (Fig. 6), and this DNA would not form consecutive planes of G quartets.

If it is not for purposes of G-quartet formation, then why is G clustering more important than mere G-richness for R-loop formation. One possibility relates to the initiation of the R-loop. Clearly, the initiation event requires that a segment of the nascent RNA begin to thread back. This thread back must begin at a few nucleotides (a nucleation site) because the template and nontemplate strands of DNA would not be open for a sufficient length to permit a long segment of RNA to anneal all at once. The initiation or nucleation site would optimally contain more than one G. Hence, G clusters would be favored for this R-loop initiation phase rather than for any postinitiation stabilization phase (such as G-quartet formation).

Short R-loops may be less stable because of the ability of the nontemplate DNA strand to branch migrate so as to displace the RNA of the R-loop. When the R-loop achieves sufficient size, displacement of the RNA due to branch migration of the DNA may be inefficient. We saw no evidence of any R-loops extending downstream of the switch sequences in the present study. Whether R-loops extend downstream (or whether branch migration occurs so as to extend R-loops further downstream) is almost certainly a function of the sequence downstream of the switch regions. For all of the substrates here, the G density falls sharply to a random G density (ca. 20 to 25%) immediately after the last switch repeat. This is in contrast to switch regions in vivo, such as Sμ and Sγ3, where the G density decreases gradually over several hundred base pairs and, hence, where R-loops extend downstream of the core repeat region (12, 13). Therefore, it seems that the downstream endpoint of R-loops is determined by the G density, and this determines whether the nascent RNA or the nontemplate DNA strand is favored for base pairing with the DNA template strand.

The steep dependence of R-loop formation on G clustering and high G density is noteworthy in an evolutionary context. CSR evolved over a hundred million years after AID had evolved for its function in somatic hypermutation (2, 15, 39). Amphibians have class switch regions that are rich in preferred AID sites (WRC) but are not G-rich on the nontemplate strand (47). Mice and humans have switch regions that not only are uniformly G-rich on the nontemplate strand but also contain clusters of G's, and all of these switch regions are G-rich across much of the repetitive core regions. We speculate that the G clustering and the overall G-richness of mammalian switch regions evolved to drive efficient R-loop formation so as to make a more efficient single-stranded DNA target at which AID can act. Based on our studies here, the mammalian switch regions are at approximately the G-clustering and G-density level that is needed to efficiently form R-loops. From an evolutionary standpoint, there would have been little reason for the G clustering and G density to evolve to even higher levels, once they had reached a sufficient level. The fact that the G clustering is close to the minimum needed for efficient R-loop formation is yet another reason for regarding R-loop formation as the basis for the high G clustering of the nontemplate strand. Otherwise, it is unclear why the G clusters would evolve to precisely this critical point.

The contribution of R-loop formation to mammalian class switch recombination may be ∼4-fold for each switch region, based on the fact that the inversion of Sγ1 results in a 4-fold drop in CSR (34). The substitution of a Xenopus Sμ region in place of Sγ1 also shows a fourfold reduction, and this is consistent with the Sγ1 inversion data because the Xenopus segment does not form R-loops (47). Hence, the downstream (acceptor) switch regions appear to have evolved a G-richness on the top strand to improve their use as targets by the single-strand specific AID enzyme. Although this enrichment may only be ∼4-fold for each switch region, this may improve overall CSR substantially based on the fact that the ratio of switched isotypes to IgM is often 100-fold or more in mammals but is typically 1 or less in Xenopus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chih-Lin Hsieh for advice and members of the Lieber lab for helpful suggestions.

This study was supported by NIH grants to M.R.L. D.R. was supported in part by the Cellular, Biochemical, and Molecular Training Program.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 October 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bardwell, P. D., C. J. Woo, K. Wei, Z. Li, A. Martin, S. Z. Sack, T. Parris, W. Edelmann, and M. D. Scharff. 2004. Altered somatic hypermutation and reduced class-switch recombination in exonuclease 1-mutant mice. Nat. Immunol. 5224-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barreto, V. M., Q. Pan-Hammarstrom, Y. Zhao, L. Hammarstrom, Z. Misulovin, and M. C. Nussenzweig. 2005. AID from bony fish catalyzes class switch recombination. J. Exp. Med. 202733-738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu, U., J. Chaudhuri, R. T. Phan, A. Datta, and F. W. Alt. 2007. Regulation of activation induced deaminase via phosphorylation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 596129-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bransteitter, R., P. Pham, M. D. Scharff, and M. F. Goodman. 2003. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase deaminates deoxycytidine on single-stranded DNA but requires the action of RNase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1004102-4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhuri, J., and F. W. Alt. 2004. Class-switch recombination: interplay of transcription, DNA deamination, and DNA repair. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4541-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels, G. A., and M. R. Lieber. 1995. RNA:DNA complex formation upon transcription of immunoglobulin switch regions: implications for the mechanism and regulation of class switch recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 235006-5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drolet, M., S. Broccoli, F. Rallu, C. Hraiky, C. Fortin, E. Masse, and I. Baaklini. 2003. The problem of hypernegative supercoiling and R-loop formation in transcription. Front. Biosci. 8d210-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunnick, W. A., G. Z. Hertz, L. Scappino, and C. Gritzmacher. 1993. DNA sequence at immunoglobulin switch region recombination sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 21365-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duquette, M. L., P. Handa, J. A. Vincent, A. F. Taylor, and N. Maizels. 2004. Intracellular transcription of G-rich DNAs induces formation of G-loops, novel structures containing G4 DNA. Genes Dev. 181618-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan, J., Y. Matsumoto, and D. M. Wilson. 2006. Nucleotide sequence and DNA secondary structure, as well as replication protein A, modulate the single-stranded abasic endonuclease activity of APE1. J. Biol. Chem. 2813889-3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gritzmacher, C. A. 1989. Molecular aspects of heavy-chain class switching. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 9173-200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang, F.-T., K. Yu, B. B. Balter, E. Selsing, Z. Oruc, A. A. Khamlichi, C.-L. Hsieh, and M. R. Lieber. 2007. Sequence dependence of chromosomal R-loops at the immunoglobulin heavy chain Smu class switch region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 275921-5932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang, F.-T., K. Yu, C.-L. Hsieh, and M. R. Lieber. 2006. The downstream boundary of chromosomal R-loops at murine switch regions: implications for the mechanism of class switch recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1035030-5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huertas, P., and A. Aguilera. 2003. Cotranscriptionally formed DNA:RNA hybrids mediate transcription elongation impairment and transcription-associated recombination. Mol. Cell 12711-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichikawa, H. T., M. P. Sowden, A. T. Torelli, J. Bachl, P. Huang, G. S. Dance, S. H. Marr, J. Robert, J. E. Wedekind, H. C. Smith, and A. Bottaro. 2006. Structural phylogenetic analysis of activation-induced deaminase function. J. Immunol. 177355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai, K., G. Slupphaug, W. I. Lee, P. Revy, S. Nonoyama, N. Catalan, L. Yel, M. Forveille, B. Kavli, H. E. Krokan, H. D. Ochs, A. Fischer, and A. Durandy. 2003. Human uracil-DNA glycosylase deficiency associated with profoundly impaired immunoglobulin class-switch recombination. Nat. Immunol. 41023-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer, P. R., and R. R. Sinden. 1997. Measurement of unrestrained negative supercoiling and topological domain size in living human cells. Biochemistry 363151-3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, D. Y., and D. A. Clayton. 1996. Properties of a primer RNA-DNA hybrid at the mouse mitochondrial DNA leading-strand origin of replication. J. Biol. Chem. 27124262-24269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, X., and J. L. Manley. 2005. Inactivation of the SR protein splicing factor ASF/SF2 results in genomic instability. Cell 122365-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masukata, H., and J. Tomizawa. 1990. A mechanism of formation of a persistent hybrid between elongating RNA and template DNA. Cell 62331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min, I. M., L. R. Rothlein, C. E. Schrader, J. Stavnezer, and E. Selsing. 2005. Shifts in targeting of class switch recombination sites in mice that lack mu switch region tandem repeats or Msh2. J. Exp. Med. 2011885-1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Min, I. M., C. E. Schrader, J. Vardo, T. M. Luby, N. D'Avirro, J. Stavnezer, and E. Selsing. 2003. The Smu tandem repeat region is critical for Ig isotype switching in the absence of Msh2. Immunity 19515-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Min, I. M., and E. Selsing. 2005. Antibody class switch recombination: roles for switch sequences and mismatch repair proteins. Adv. Immunol. 87297-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muramatsu, M., V. Sankaranand, S. Anant, M. Sugai, K. Kinoshita, N. Davidson, and T. Honjo. 1999. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27418470-18476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen-Mahrt, S. K., R. S. Harris, and M. S. Neuberger. 2002. AID mutates Escherichia coli suggesting a DNA deamination mechanism for antibody diversification. Nature 41899-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrini, J., and W. Dunnick. 1989. Products and implied mechanism of H chain switch recombination. J. Immunol. 1422932-2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rada, C., G. T. Williams, H. Nilsen, D. E. Barnes, T. Lindahl, and M. S. Neuberger. 2002. Immunoglobulin isotype switching is inhibited and somatic hypermutation perturbed in UNG-deficient mice. Curr. Biol. 121748-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reaban, M. E., and J. A. Griffin. 1990. Induction of RNA-stabilized DNA conformers by transcription of an immunoglobulin switch region. Nature 348342-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reaban, M. E., J. Lebowitz, and J. A. Griffin. 1994. Transcription induces the formation of a stable RNA:DNA hybrid in the immunoglobulin alpha switch region. J. Biol. Chem. 26921850-21857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts, R. W., and D. M. Crothers. 1992. Stability and properties of double and triple helices: dramatic effects of RNA or DNA backbone composition. Science 2581463-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ronai, D., M. D. Iglesias-Ussel, M. Fan, Z. Li, A. Martin, and M. D. Scharff. 2007. Detection of chromatin-associated single-stranded DNA in regions targeted for somatic hypermutation. J. Exp. Med. 204181-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saenger, W. 1984. Principles of nucleic acid structure. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY.

- 33.Selsing, E. 2006. Ig class switching: targeting the recombinational mechanism. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18249-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shinkura, R., M. Tian, C. Khuong, K. Chua, E. Pinaud, and F. W. Alt. 2003. The influence of transcriptional orientation on endogenous switch region function. Nat. Immunol. 4435-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stavnezer, J., and C. T. Amemiya. 2004. Evolution of isotype switching. Semin. Immunol. 16257-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stavnezer, J., and S. Sirlin. 1986. Specificity of immunoglobulin heavy chain switch correlates with activity of germline heavy chain genes prior to switching. EMBO J. 595-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szurek, P., J. Petrini, and W. Dunnick. 1985. Complete nucleotide sequence of the murine g3 switch region and analysis of switch recombination sites in two γ3-expressing hybridomas. J. Immunol. 135620-626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian, M., and F. W. Alt. 2000. Transcription induced cleavage of immunoglobulin switch regions by nucleotide excision repair nucleases in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 27524163-24172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wakae, K., B. G. Magor, H. Saunders, H. Nagaoka, A. Kawamura, K. Kinoshita, T. Honjo, and M. Muramatsu. 2006. Evolution of class switch recombination function in fish activation-induced cytidine deaminase, AID. Int. Immunol. 1841-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westover, K. D., D. A. Bushnell, and R. D. Kornberg. 2004. Structural basis of transcription: separation of RNA from DNA by RNA polymerase II. Science 3031014-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu, B., and D. A. Clayton. 1996. RNA-DNA hybrid formation at the human mitochondrial heavy-strand origin ceases at replication start sites: an implication for RNA-DNA hybrids serving at primers. EMBO J. 153135-3143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu, L., B. Gorham, S. C. Li, A. Bottaro, F. W. Alt, and P. Rothman. 1993. Replacement of germ-line ɛ promoter by gene targeting alters control of immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 903705-3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu, K., F. Chedin, C.-L. Hsieh, T. E. Wilson, and M. R. Lieber. 2003. R-loops at immunoglobulin class switch regions in the chromosomes of stimulated B cells. Nat. Immunol. 4442-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu, K., F. T. Huang, and M. R. Lieber. 2004. DNA substrate length and surrounding sequence affect the activation induced deaminase activity at cytidine. J. Biol. Chem. 2796496-6500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu, K., and M. R. Lieber. 2003. Nucleic acid structures and enzymes in the immunoglobulin class switch recombination mechanism. DNA Repair 21163-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu, K., D. Roy, M. Bayramyan, I. S. Haworth, and M. R. Lieber. 2005. Fine-structure analysis of activation-induced deaminase accessbility to class switch region R-loops. Mol. Cell. Biol. 251730-1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zarrin, A. A., F. W. Alt, J. Chaudhuri, N. Stokes, D. Kaushal, L. DuPasquier, and M. Tian. 2004. An evolutionarily conserved target motif for immunoglobulin class-switch recombination. Nat. Immunol. 51275-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.