Abstract

The Kluyveromyces lactis ter1-16T strain contains mutant telomeres that are poorly bound by Rap1, resulting in a telomere-uncapping phenotype and significant elongation of the telomeric DNA. The elongated telomeres of ter1-16T allowed the isolation and examination of native yeast telomeric DNA by electron microscopy. In the telomeric DNA isolated from ter1-16T, looped molecules were observed with the physical characteristics of telomere loops (t-loops) previously described in mammalian and plant cells. ter1-16T cells were also found to contain free circular telomeric DNA molecules (t-circles) ranging up to the size of an entire telomere. When the ter1-16T uncapping phenotype was repressed by overexpression of RAP1 or recombination was inhibited by deletion of rad52, the isolated telomeric DNA contained significantly fewer t-loops and t-circles. These results suggest that disruption of Rap1 results in elevated recombination at telomeres, leading to increased strand invasion of the 3′ overhang within t-loop junctions and resolution of the t-loop junctions into free t-circles.

Telomeres are the nucleoprotein structures at eukaryotic chromosome termini that cap the chromosome ends. They consist of tandem G-rich repeats that terminate in a single-stranded 3′ overhang and proteins that interact with both the single-stranded and double-stranded regions of telomeric DNA. Disruption of telomere capping can lead to one or more outcomes, including telomere fusions, increased telomeric recombination, and replicative senescence (12). In higher eukaryotes, telomeres are commonly arranged into a structure termed a telomere loop (t-loop) that involves strand invasion of the 3′ overhang into internal telomeric repeats of the same chromosome end (14). Such loops have been seen in human, murine, chicken, plant, and ciliate telomeres (5, 14, 24, 27). T-loop formation in vitro is facilitated by human TRF2 protein (1, 14, 29), and inhibition of TRF2 in vivo results in telomere dysfunction and chromosome fusions (3, 35), suggesting that the ability to stabilize t-loops may be an important part of telomeric capping.

Telomeres in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been proposed to assume a fold-back structure mediated by protein-protein interactions, although the variable telomeric-repeat sequence may or may not allow strand invasion of the 3′ overhang to generate a t-loop (10, 11). The Taz1 protein, from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, is an ortholog TRF2, and in vitro studies have shown that, like TRF2, it has the ability to arrange model telomere substrates into looped structures (32). However, direct examination of native yeast telomere architecture by electron microscopy (EM) to confirm the presence or absence of t-loops in yeast has proven problematic, due to the difficulty of isolating the short telomeres in these species. This is because long telomere restriction fragments (TRFs), which can be separated from the short genomic restriction fragments by gel filtration chromatography, are a technical requirement for observation of native telomeric DNA by EM.

While telomere attrition is most often counterbalanced by telomerase activity, homologous recombination-dependent telomere maintenance mechanisms also exist. A subset of human tumor and immortalized cells use a telomerase-independent mechanism termed alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) that is believed to be dependent on recombination (16), and recombinational telomere elongation (RTE) is well characterized in yeast mutants with telomerase deleted (23). Such mutants display gradual telomere shortening, leading to senescence. However, survivors can emerge from senescence if chromosome ends have become elongated by recombination (20, 22). Two types of survivors are characterized in S. cerevisiae: type I has short telomeres and exhibits amplification of the subtelomeric Y′ elements, while type II is similar to human ALT cells, exhibiting elongated, heterogeneous telomeric DNA (7, 20, 30). Survivors in the related budding yeast, Kluyveromyces lactis, are exclusively type II (22).

Current data support a model of type II RTE termed “roll-and-spread” in which extrachromosomal telomeric repeat (ECTR) DNA circles (t-circles), created by telomeric recombination, act as a template for rolling-circle replication, elongating one (or more) telomere (26). The elongated telomere(s) then spreads to other chromosome ends via nonreciprocal recombination events. Support for this model comes mainly from K. lactis, in which exogenous t-circles were shown to promote RTE and a DNA sequence from one elongated telomere was shown to spread to other telomeres following RTE onset (25, 26, 33). Evidence of a roll-and-spread mechanism was also observed in the mitochondria of the yeast species Candida parapsilosis, which contains linear mitochondrial DNA capped by telomeres maintained in a telomerase-independent fashion (28). Consistent with a role in RTE, t-circles are a conserved feature in human ALT cells (4, 36), S. cerevisiae survivors (18, 19), and C. parapsilosis mitochondria (31), and as described below, they likely reflect a t-loop origin. Recent data also indicate that Ku70 deletion in Arabidopsis thaliana results in t-circle formation and the growth of callus cultures with ALT-like telomeric phenotypes (39).

K. lactis provides an excellent opportunity for investigating telomere structure in a yeast species. Unlike S. cerevisiae, the 25-bp K. lactis telomeric repeat contains TA dinucleotides that allow interstrand cross-linking by psoralen (Fig. 1D), a necessary step for maintaining t-loop structure during isolation (14). K. lactis mutants with telomeres long enough to permit isolation from the bulk genomic DNA following restriction enzyme fragmentation are available, either with or without obvious telomere-capping defects (34). The ter1-16T mutant, in particular, is well suited for such studies. Mutation of the telomerase RNA gene in ter1-16T generates telomeric repeats with a base change that alters the binding site for Rap1, a protein crucial to telomere length regulation and capping (Fig. 1D) (34). The ter1-16T mutation leads to long, uncapped telomeres with abnormally long 3′ overhangs, both of which can be suppressed by RAP1 overexpression (34). ter1-16T cells have also been shown to produce small t-circles using homologous recombination, and this can be inhibited by RAD52 deletion (15).

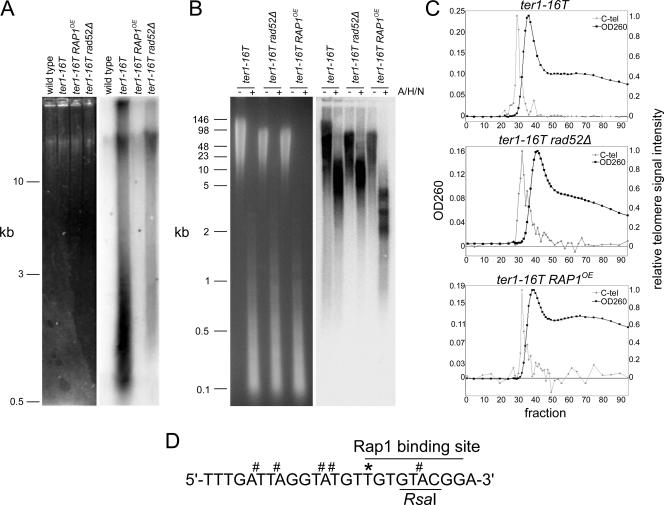

FIG. 1.

Phenotypic characteristics and enrichment of telomeric DNA from K. lactis strains. (A) Detection of single-stranded G-rich telomeric DNA by in-gel hybridization without denaturation. Uncut genomic DNA (1 μg) was separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and the total DNA content was visualized by ethidium staining and UV light (left). The gel was subsequently in-gel hybridized with a 32P-labeled K. lactis C-strand oligonucleotide telomere probe ([32P]-C-tel) and visualized using a PhosphorImager. Because the gel was not denatured prior to hybridization, the signal represents native single-stranded G-rich telomeric DNA. Size markers are indicated on the left. (B) Measurement of telomere length by PFGE, followed by denaturation and in-gel hybridization. Genomic DNA (2 μg) either uncut (−) or digested with A/H/N (+) was separated by PFGE. The total DNA content as determined in panel A is shown on the left. The telomeric DNA signal as determined by in-gel hybridization with the [32P]-C-tel probe following denaturation of the gel and visualization as in panel A is shown on the right. Size markers are shown on the left. We believe differences in the amounts of telomeric material migrating at <1 kb in panels A and B reflect the different isolation and experimental conditions used in these two experiments. (C) TRFs from the indicated strains (>0.5 mg) were separated by gel filtration chromatography through Bio-Gel A-15m. Equal amounts of material from selected fractions (50 ng or 100 μl for samples with ≤0.5 ng/μl DNA) were bound to a nylon membrane and probed with the [32P]-C-tel probe. The signal was quantified using a PhosphorImager and plotted as relative telomeric intensity. Elution profiles from cross-linked samples are shown here. (D) Telomere sequence of ter1-16T. The RsaI (5′-GTAC-3′) and Rap1 binding sites are indicated. * marks the G-to-T change at position 16, and # indicates proposed psoralen cross-linking sites at TA dinucleotides.

In this study, we have isolated telomeric DNA from the K. lactis ter1-16T strain for direct examination by EM and 2D gel analysis. We show that telomeric DNA from ter1-16T cells contains looped molecules of telomeric DNA with the physical characteristics of t-loops previously isolated from mammalian and plant cells, as well as abundant t-circles ranging up to the size of an entire telomere. In contrast, telomeric DNA from ter1-16T RAP1OE (overexpressing RAP1) and ter1-16T rad52Δ cells contained significantly fewer t-loops and t-circles. Cumulatively, these data suggest that increased recombination at K. lactis telomeres in the absence of Rap1 results in increased strand invasion at t-loop junctions and resolution of t-loops by homologous recombination into free t-circles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains.

The telomerase mutant ter1-16T and the double mutant ter1-16T rad52Δ were constructed as described previously in a His-positive revertant of the 7B520 strain (34). The ter1-16T RAP1OE strain was generated by transforming ter1-16T with pCXJ3+RAP1 (a gift from Anat Krauskopf). ter1-16T and ter1-16T rad52Δ strains were transformed with pCXJ3 lacking a transgene. Transformants were selected on media lacking uracil and then grown in liquid yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium containing 125 μg/ml G418, previously shown to maintain >100 copies of plasmid per cell (37).

Psoralen cross-linking and genomic-DNA isolation and digestion.

K. lactis cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 15 (postexponential phase). One liter of cells was spheroplasted, and nuclear isolation was performed as described previously (17) using 100 μg/ml Zymolyase 100T (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan). Nuclei were treated with psoralen and UV light, and the genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (5, 14). Prior to restriction digestion, genomic DNA was incubated with Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA binding protein (SSB) to protect single-stranded DNA segments (5, 6) and then was digested for 2 h at 37°C with AluI, HpaII, and NlaIII (New England Biolabs [NEB], Beverly, MA) at 1 unit/μg of DNA each. These enzymes were chosen for their lack of single-stranded nuclease activity (NEB technical support). The mixture was supplemented with an equal amount of enzyme plus 20 μg/ml RNase A for an additional 2 h of incubation. Digestions were checked for completeness on a 1% agarose gel, and if required, more enzyme was added. The digested DNA was purified and prepared for gel filtration chromatography as previously described (5, 14).

Gel filtration chromatography.

TRFs were fractionated as described previously (5). The telomeric contents of the eluted fractions were determined by slot blot analysis (5) using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide K. lactis C-strand telomere probe and quantified using a Storm 840 PhosphorImager and associated software (Molecular Dynamics, Piscataway, NJ).

EM.

DNA samples were prepared for EM by surface spreading on a denatured protein film (14). When DNA from the gel filtration column was subsequently digested with RsaI or MseI (NEB), the sample was brought to 0.1 μg/ml SSB in 1× NEB buffer 1, incubated on ice for 30 min, and then treated with 0.5 unit of restriction enzyme for 15 min at 37°C. EDTA was added to 5 mM, and then the mixture was passed through a G50 Sephadex (Pharmacia, New York, NY) spin column and prepared for EM by surface spreading. Staining of single-stranded DNA with SSB was done on ice for 30 min in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, with 0.2 μg/ml SSB. The mixture was fixed with 0.6% glutaraldehyde for 5 min at room temperature and then directly mounted onto carbon foils for EM (13). All samples were examined in a Philips/FEI Tecnai 12 transmission electron microscope (Eindhoven, The Netherlands), and molecule measurements were done using Digital Micrograph software (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA). Statistical analyses were done using GraphPad software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA), and images were prepared for publication using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Agarose gel electrophoresis.

DNA isolation and detection of single-stranded G-rich telomeric DNA by in-gel hybridization without denaturation were done as previously described (34). Measurement of TRF length by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was done using aliquots from non-cross-linked preparations for future EM analysis, and the telomeric material was detected by denaturation and in-gel hybridization as described previously (5). For standard two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis, restriction fragments were separated in the first dimension in 0.6% gold agarose (ISC Bio Express, Kaysville, UT) in 0.5× TBE (44.5 mM Tris base, 44.5 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA) at 1 V/cm for 13.5 h. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by UV light, and the appropriate lanes were excised. A 1.1% agarose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) gel in 0.5× TBE containing 300 ng/ml ethidium bromide was poured around the excised slab. Second-dimension electrophoresis was carried out in 0.5× TBE containing 300 ng/ml ethidium bromide at 6 V/cm for 3 h. The telomeric content was determined by in-gel hybridization or Southern blotting, following a denaturation step with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide K. lactis C- or G-strand telomere probe. Circular-DNA markers were made by diluting HindIII-digested λ DNA to 10 ng/μl and ligating it overnight at 16°C with T4 DNA ligase. High-percentage agarose-chloroquine 2D gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting were done as previously described (15). All hybridizations were visualized using a PhosphorImager.

RESULTS

ter1-16T has a RAD52- independent telomere-capping defect that is suppressed by overexpression of RAP1.

In this study, we employed K. lactis strains that possess a mutation in the 16th position within the telomerase RNA subunit (ter1-16T). This mutation confers telomerase-mediated addition of mutant telomeric repeats that are poorly bound by Rap1 onto the chromosome ends. Two of the strains used in this study, ter1-16T and ter1-16T rad52Δ, possess long, uncapped telomeres, with the latter strain not exhibiting telomere recombination and ECTR DNA due to the absence of RAD52 (34). Additionally, we used the RAP1-overexpressing strain ter1-16T RAP1OE, in which the telomere-uncapping phenotype is suppressed due to an abundance of Rap1p (34).

Undigested genomic DNA from ter1-16T, ter1-16T rad52Δ, and ter1-16T RAP1OE cells was isolated, separated by standard gel electrophoresis, and subjected to in-gel hybridization under conditions that detected native single-stranded G-rich telomeric DNA (Fig. 1A). In ter1-16T and ter1-16T rad52Δ, abundant single-stranded G-rich telomeric DNA was present, consistent with previous results (34) and indicative of an uncapped telomere state. We noted that ter1-16T rad52Δ showed a diminished amount of the small single-stranded G-rich material found in ter1-16T (Fig. 1A) (34). In the ter1-16T RAP1OE strain, the single-stranded G-rich telomeric signal was absent, indicating effective suppression of the uncapping phenotype (Fig. 1A).

Telomere length was assayed in all three strains by separation of uncut or AluI/HpaII/NlaIII (A/H/N)-digested genomic DNA using PFGE. A/H/N digestion of K. lactis genomic DNA leaves an average of 370 bp (estimated range, 145 to 450 bp) of subtelomeric DNA on the resulting telomere fragments. Consistent with previous results, ter1-16T contained elevated levels of ECTR DNA, exhibited by a smear of low-molecular-weight telomeric DNA between 5 kb and 0.5 kb in the uncut lanes (Fig. 1B), while the ter1-16T rad52Δ and ter1-16T RAP1OE strains lacked similar signals in the uncut material, indicating a reduction in ECTR DNA material. The ter1-16T and ter1-16T rad52Δ strains exhibited heterogeneous A/H/N-derived TRFs up to greater than 20 kb in length. A/H/N-derived TRFs from ter1-16T RAP1OE were shorter, with the bulk of the signal between 1.75 and 5 kb, which is still significantly greater than the ∼300-bp telomeres in wild-type K. lactis.

Enrichment of TRFs from ter1-16T, ter1-16T rad52Δ, and ter1-16T RAP1OE by gel filtration chromatography.

Observation of t-loop structures by EM is dependent upon first psoralen photo-cross-linking the nuclei, which is proposed to establish covalent bonds between the invading 3′ overhang and the duplex telomeric DNA (8, 14). Crude nuclei from ter1-16T, ter1-16T rad52Δ, and ter1-16T RAP1OE were psoralen photo-cross-linked, and the DNA was purified and reduced to TRFs by treatment with A/H/N. At least 0.5 mg of A/H/N-digested DNA from psoralen cross-linked or non-cross-linked samples from each of the strains was chromatographed over Bio-Gel A-15m. Elution profiles comparing the DNA concentrations and telomere contents indicated that for all preparations, the telomeric DNA preceded the bulk genomic DNA, providing the required enrichment for EM analysis (Fig. 1C).

Visualization of TRFs in ter1-16T and related strains.

DNA from the high-molecular-weight, telomere-enriched fractions was prepared for EM. We quantified fractions starting at the peak of the telomere signal as determined by blotting and then examined earlier-eluting (higher-molecular-weight) fractions until the DNA concentration within the fractions became too low for EM analysis (Fig. 1C). Higher-numbered (lower-molecular-weight) fractions beyond the telomere peak contained increasing amounts of small DNA molecules, presumably representing the bulk genomic DNA. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the results for each preparation and statistical comparisons between conditions.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the EM observations from ter1-16T, ter1-16T RAP1OE, and ter1-16T rad52Δ

| Sample | Total n | No. linear (%) | No. loop (%) | No. circle (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ter1-16T | ||||

| Cross-linked (prepa 1) | 540 | 476 (88.2) | 19 (3.5) | 45 (8.3) |

| Non-cross-linked (prep 1) | 435 | 423 (97.2) | 5 (1.2) | 7 (1.6) |

| Cross-linked (prep 2) | 617 | 526 (85.3) | 34 (5.5) | 57 (9.2) |

| Non-cross-linked (prep 2) | 1,622 | 1,560 (96.2) | 22 (1.3) | 40 (2.5) |

| ter1-16T RAP1OE | ||||

| Cross-linked (prep 1) | 871 | 843 (96.8) | 11 (1.3) | 17 (1.9) |

| Non-cross-linked (prep 1) | 2,930 | 2,840 (97.0) | 45 (1.5) | 45 (1.5) |

| Cross-linked (prep 2) | 2,516 | 2,434 (96.7) | 38 (1.5) | 44 (1.8) |

| Non-cross-linked (prep 2) | 2,117 | 2,034 (96.1) | 59 (2.8) | 24 (1.1) |

| ter1-16T rad52Δ | ||||

| Cross-linked (prep 1) | 1,471 | 1,438 (97.8) | 14 (0.9) | 19 (1.3) |

| Non-cross-linked (prep 2) | 450 | 444 (98.6) | 3 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) |

| Cross-linked (prep 2) | 1,423 | 1,371 (96.3) | 37 (2.6) | 15 (1.1) |

| Non-cross-linked (prep 2) | 1,179 | 1,148 (97.4) | 15 (1.3) | 16 (1.3) |

Prep, preparation.

TABLE 2.

Statistical significance of EM observationsa

| Comparison | Linear (n) | Loop (n) | Circle (n) | P value (linear/looped) | P value (linear/circle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ter1-16T cross-linked | 1,002 | 53 | 102 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| ter1-16T non-cross-linked | 1,983 | 27 | 47 | ||

| ter1-16T RAP1OE cross-linked | 3,277 | 49 | 61 | 0.041 | 0.121 |

| ter1-16T RAP1OE non-cross-linked | 4,874 | 104 | 69 | ||

| ter1-16T rad52Δ cross-linked | 2,809 | 51 | 34 | 0.083 | 0.961 |

| ter1-16T rad52Δ non-cross-linked | 1,592 | 18 | 19 | ||

| ter1-16T cross-linked | 1,002 | 53 | 102 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| ter1-16T RAP1OE cross-linked | 3,277 | 49 | 61 | ||

| ter1-16T cross-linked | 1,002 | 53 | 102 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| ter1-16T rad52Δ cross-linked | 2,809 | 51 | 34 |

Numerical data from preparations 1 and 2 for each condition were pooled, and significance was determined using a two-tailed chi-squared analysis without Yates correction.

The sizes of DNA molecules in the earliest-eluting telomere-enriched fractions in ter1-16T and ter1-16T rad52Δ ranged up to 30 kb, with an average size of approximately 7 kb, while fractions containing the peak telomeric signal had an average DNA molecule size of approximately 4 kb. In the telomere-enriched fractions from ter1-16T RAP1OE, the average DNA length was smaller, 2 to 4 kb, consistent with a decreased telomere length in this strain. As observed in previous studies of t-loops, linear DNA molecules were the most common structural form in the telomere-enriched fractions and are consistent with telomeres that were not arranged into a t-loop, telomeres in which strand invasions were not maintained during the enrichment procedure, or nontelomeric contaminants (4, 5, 14). Given that A/H/N digestion of whole K. lactis DNA is expected to produce only three nontelomeric restriction fragments of greater than 1,500 bp in size (genomic fragments of 1,787 and 1,731 bp and a 1,546-bp mitochondrial fragment), our observation of DNA fragments consistently larger than 2 kb suggests that the vast majority of the DNA molecules we observed were telomeric in nature.

Looped molecules are present in the psoralen cross-linked, telomere-enriched fractions from ter1-16T.

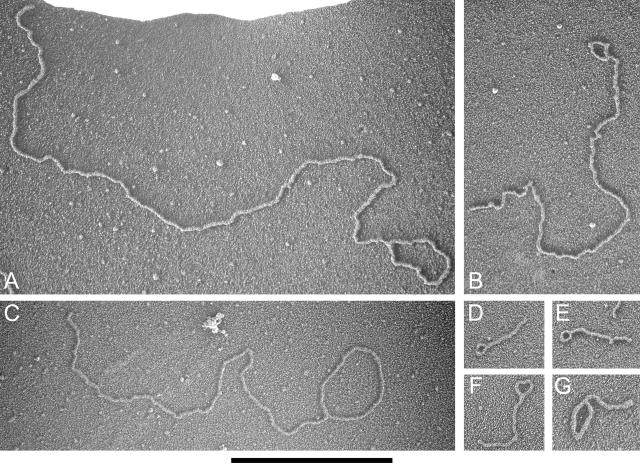

Lariat molecules consistent with the t-loop structure, described as a double-stranded DNA circle with a double-stranded DNA tail, were found in the telomere-enriched cross-linked fractions from ter1-16T (Fig. 2 and Table 1). A 3.6-fold-greater abundance in the percentage of looped molecules was observed in the cross-linked ter1-16T samples than in non-cross-linked samples, indicating a significant psoralen contribution to the stabilization of the loop structure (Fig. 3A and Tables 1 and 2). Additionally, when the cross-linked samples from ter1-16T RAP1OE and ter1-16T rad52Δ were compared to the cross-linked fractions from ter1-16T, they had significantly fewer looped molecules, 3.2- and 2.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 3A and Tables 1 and 2).

FIG. 2.

Looped molecules in the high-molecular-weight, telomere-enriched fractions from ter1-16T. (A to G) Electron micrographs of looped molecules present in the high-molecular-weight fractions from ter1-16T. Loop and tail sizes are 3.4 and 15.0, 0.8 and 6.5, 4.2 and 8.7, 0.4 and 0.7, 0.5 and 1.0, 0.6 and 1.2, and 1.3 and 0.8 kb for panels A through G, respectively. DNA was prepared for EM by surface spreading on a denatured protein film and rotary shadow casting. The images are shown in negative contrast. The bar is equivalent to 3 kb.

FIG. 3.

Looped and circular molecules observed in ter1-16T are consistent with t-loops and t-circles. (A) Abundances of looped molecules observed in the psoralen cross-linked (+) and non-cross-linked (−) samples from ter1-16T, ter1-16T RAP1OE, and ter1-16T rad52Δ. (B) Distribution of the total length (loop plus tail) of looped molecules in the high-molecular-weight, telomere-enriched fractions from ter1-16T (n = 94) and ter1-16T RAP1OE (n = 91). (C) Percentages of looped molecules observed in the indicated cross-linked fractions from ter1-16T preparation 2 after initial digestion with A/H/N (initial) and then subsequent digestions with MseI or RsaI. (D) Distribution of the abundances of circular molecules observed in the psoralen cross-linked (+) and non-cross-linked (−) samples from ter1-16T, ter1-16T RAP1OE, and ter1-16T rad52Δ. (E) Percentages of circular molecules observed in the indicated cross-linked fractions from ter1-16T preparation 2 after initial digestion with A/H/N (initial) and then subsequent digestions with MseI or RsaI. (F) Size distribution of measured circular molecules (n = 102) and the loop portions of t-loops (n = 94) from ter1-16T.

The sizes of the looped molecules (loop plus tail) in ter1-16T ranged from 0.7 to 27.2 kb (n = 94; mean = 6.1 kb; median = 3.6 kb) (Fig. 3B). Forty-eight percent of looped molecules were less than 3 kb, with the remaining 52% in a distribution ranging from 3 to 30 kb. The latter fraction correlates well with the range of telomere sizes as measured by PFGE, consistent with their being telomeric DNA (compare Fig. 1B and 3B). The smaller loops are consistent with the low-molecular-weight ECTR DNA or possibly the shortest chromosomal telomeres in ter1-16T. A lower abundance of looped molecules was observed in ter1-16T RAP1OE; however, analysis of a large number of total molecules provided enough looped molecules to measure and analyze their size distribution (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the shortened telomeres, the majority of looped molecules in ter1-16T RAP1OE were small, with 96% less than 3 kb (n = 91; range, 0.5 to 20.1 kb; mean = 1.51 kb; median = 1.08 kb). Not enough looped molecules were observed in ter1-16T rad52Δ for accurate size quantification.

Looped molecules from ter1-16T are composed of telomeric DNA and are structurally similar to t-loops from higher eukaryotes.

The 25-bp telomeric repeat in K. lactis contains a single RsaI site and no sites for MseI (Fig. 1D, MseI digests 5′-TTAA-3′). Incubation of multiple fractions from ter1-16T cross-linked preparation 2, with MseI, resulted in an increase in the abundance of looped molecules (Fig. 3C). Because these fractions correspond to the peak of the telomere signal in their respective elution profiles, we believe that this reflects the digestion by MseI of contaminating nontelomeric DNA in these late-eluting fractions, effecting a further purification step. In contrast, digestion of the same fractions with RsaI resulted in the complete disappearance of looped molecules and the almost complete reduction of the DNA within these fractions to sizes smaller than the limit of EM detection (Fig. 3C). The resistance of looped molecules from ter1-16T to MseI and their sensitivity to RsaI strongly suggests they are composed of telomeric DNA.

In the t-loop structure, a segment of single-stranded DNA is predicted to be present at the t-loop junction, due to strand invasion of the 3′ overhang to generate the displacement loop (14). Consistent with this, E. coli SSB localized to the loop junction in 35% of t-loops isolated from human and mouse cells (14). We incubated DNA from the ter1-16T telomere-enriched, cross-linked fractions with E. coli SSB and directly mounted the samples onto carbon-coated EM grids. In these experiments, the SSB protein localized to the loop junctions of the majority of the looped molecules, suggestive of strand invasion-mediated telomere looping (Fig, 4A to C). The amounts of the SSB at the loop junction varied between a single SSB particle and large amounts of protein, suggesting considerable variability in the amount of single-stranded DNA present. This variability is likely due to heterogeneity in the elongated 3′ overhangs in ter1-16T, which strand invade to form the displacement loop. Consistent with this, we also observed linear molecules from ter1-16T with variable amounts of SSB on one end (Fig. 4D and E).

FIG. 4.

SSB-bound looped and linear molecules from the high-molecular-weight, cross-linked ter1-16T fractions. (A to C) Looped molecules with SSB localized to the loop junction. Loop and tail sizes are 0.3 and 5.7, 0.4 and 1.5, and 0.7 and 0.6 kb for panels A through C, respectively. (D and E) Linear molecules with SSB localized to a single molecule end. The length of the double-stranded DNA in panel D is 3.4 kb. In panel E, the total length of the double-stranded DNA for the molecule shown is 16.1 kb, with most of double-stranded DNA outside of the image border. Samples were directly mounted onto thin carbon-coated foils and rotary shadow cast with tungsten. The white arrows indicate the locations of SSB protein. The images are shown in negative contrast. The bar is equivalent to 1 kb.

Heterogeneous telomere circles in ter1-16T.

Genetic data from K. lactis suggests that RTE in ter1Δ survivors is dependent on rolling-circle replication initiated on circular telomeric DNA as small as 100 bp (26). Previous examination of gel-isolated low-molecular-weight ECTR DNA from ter1-16T indicated that in this strain, small single-stranded and double-stranded t-circles were present, and that they ranged upward in size from ∼100 bp/nucleotide (15). In the telomere-enriched, cross-linked fractions from ter1-16T, we observed an abundance of circular DNA molecules (Fig. 5), ranging from 0.5 to 19.3 kb, with 84%, of the circles measuring <3 kb in size (n = 102; mean = 2.1 kb; median = 1.2 kb). DNA circles in psoralen cross-linked preparations from ter1-16T cells were significantly more abundant, 4.7- and 7.3-fold more prevalent on average, than in the psoralen cross-linked preparations from ter1-16T RAP1OE and ter1-16T rad52Δ, respectively (Fig. 3D and Tables 1 and 2). Circular molecules in ter1-16T RAP1OE were also generally small, with 96% measuring <3 kb (n = 83; mean = 1.2 kb; median = 0.8 kb).

FIG. 5.

Extrachromosomal DNA circles from ter1-16T. (A to J) Electron micrographs of circular DNA molecules observed in the telomere-enriched fractions from ter1-16T. The circle lengths are 8.5, 4.6, 4.6, 3.6, 3.3, 0.9, 0.8, 0.7, 1.2, and 0.9 kb for panels A through J, respectively. DNA was prepared for EM as in Fig. 2. The images are shown in negative contrast. The bar is equivalent to 2 kb.

To determine if the circular material observed by EM contained telomeric sequences, we separated A/H/N-digested genomic DNA from all three strains by standard 2D gel electrophoresis and probed in gel with telomere-specific probes. TRFs from ter1-16T contained a strong band of telomeric material migrating in an arc consistent with open circular-form DNA, in both the psoralen cross-linked and non-cross-linked samples, suggesting that the DNA circles observed by EM were t-circles (Fig. 6A and data not shown). Circle abundance in ter1-16T as assayed by both EM and 2D gels was enriched by psoralen cross-linking (Fig. 3D, Table 1, and data not shown). This might indicate that some of the circles are not covalently closed but instead associated by homologous base pairing that was stabilized by psoralen cross-linking. Equivalent t-circle arcs were not observed in any of the psoralen cross-linked or non-cross-linked samples from ter1-16T RAP1OE or ter1-16T rad52Δ (Fig. 6B and data not shown). In addition, we observed an arc of telomeric signal derived solely from the G-rich strand, with the bulk of the material migrating between 2 and 0.5 kb, which ran below the arc of linear double-stranded DNA in ter1-16T and ter1-16T rad52Δ, but not ter1-16T RAP1OE (Fig. 6B). This is consistent with material in this arc being single-stranded G-rich ECTR DNA, suggesting that the increased single-stranded G-rich signal associated with telomere uncapping in budding yeast may be derived from both increased overhang length and ECTR DNA.

FIG. 6.

t-circles are greatly diminished in the ter1-16T rad52Δ and ter1-16T RAP1OE strains. (A) Psoralen cross-linked, A/H/N-digested ter1-16T genomic DNA (8 μg) was separated by standard 2D agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of circularized HindIII λ fragments. The total DNA was visualized by ethidum bromide staining and UV light, and the telomeric material was detected by Southern blotting using a K. lactis [32P]-G-tel oligonucleotide probe. The blot was subsequently stripped and hybridized with 32P-labeled HindIII λ fragments. Super-coiled (sc) and open-circular (oc) spots are indicated, as is the remaining linear (L) telomere-derived signal. A merge of the telomeric and HindIII λ signals indicates a comigration of telomeric signal with the open-circular form controls. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the top. (B) t-circle abundances were compared between strains by separating 8 μg of A/H/N-digested genomic DNA by standard 2D gel electrophoresis. Total DNA was visualized as in panel A, and the telomeric material was detected by in-gel hybridization with a K. lactis [32P]-C-tel or [32P]-G-tel oligonucleotide probe. Linear molecular weight markers are indicated on the top. A diagram identifying the arcs of telomeric material observed in ter1-16T is shown on the bottom right. The samples shown are from psoralen cross-linked preparations. The spots present in the linear arc in the ter1-16T and ter1-16T rad52Δ ethidum-stained agarose gels running at molecular sizes of >2 kb represent linear HindIII λ marker added to the sample immediately prior to electrophoresis. (C) Uncut genomic DNA (5 μg) was separated in 2D on a 4% agarose-chloroquine gel, and the telomeric material was detected by Southern blotting with a [32P]-C-tel oligonucleotide probe. We noted that the small circular material contained an evident substructure, as observed previously (15), believed to be t-circles of increasing sizes in 25-bp increments.

Because the resolution of open circular forms in standard 2D gels is limited to circles of >2 kb in size, we separated uncut DNA from ter1-16T and ter1-16T RAP1OE on 4% agarose-chloroquine 2D gels to visualize the smaller t-circles. In these experiments, a small amount of ECTR DNA consistent with t-circles was observed in DNA isolated from ter1-16T RAP1OE cells, though an exposure three times longer was required to see a signal compared to DNA isolated from ter1-16T (Fig. 6C). The significant decrease in circles in ter1-16T RAP1OE as assayed by 2D gels is in agreement with the EM results.

Circular molecules were also quantified in the MseI and RsaI digestion experiments detailed above. In these experiments, RsaI digestion of telomere-enriched, cross-linked fractions from ter1-16T resulted in the complete disappearance of circles in one fraction and an 88% reduction in another, consistent with the circles containing telomeric DNA (Fig. 3E). MseI digestion also resulted in some reduction in circles (28% in one fraction and 21% in the other) (Fig. 3E), suggesting that treatment with MseI disrupted some t-circles or that some circles from ter1-16T observed by EM contained nontelomeric sequences.

The observation of RAD52-dependent t-circles in ter1-16T is consistent with a mechanism of circle formation due to homologous recombination resolution of the t-loop junction, resulting in a truncated telomere and a free t-circle (36). We therefore predicted a correlation in size between the loop portions of t-loops and t-circles, as observed previously in the human GM847 ALT cell line (4). In ter1-16T, there is good correlation between the sizes of t-circles and the loop portions of t-loops, with the greatest amount of discrepancy at the smaller size ranges (Fig. 3F). This likely reflects the loss of the smallest circular molecules during the gel filtration step.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used EM and gel electrophoresis to probe the structure of yeast telomeric DNA. We observed looped structures in K. lactis ter1-16T, a mutant that develops abnormally elongated telomeres as a result of a defect in the Rap1 binding site within telomeric repeats. Four lines of evidence suggest the looped molecules observed here are composed of telomeric DNA and primarily represent t-loops, structures in which a 3′ telomeric overhang has strand invaded a more internal region of the same telomere. First, the total length of the looped molecules observed by EM in the high-molecular-weight fractions tightly correlates with the telomere lengths in the strain of DNA origin. Second, the looped molecules in ter1-16T are sensitive to RsaI and resistant to MseI, consistent with the K. lactis telomeric DNA sequence. Third, the looped molecules in ter1-16T are significantly more abundant in the psoralen cross-linked fractions, in accordance with previous observations indicating a requirement for psoralen cross-linking to maintain the t-loop structure (14). Fourth, SSB localizes to the loop junctions of looped molecules in ter1-16T, as seen in previous observations in mammalian cells, suggesting the presence of single-stranded DNA at the loop junction due to the presence of a D-loop (14). Two lines of evidence also suggest the circular molecules observed in these studies by EM contain telomeric DNA. First, like the looped molecules, circles in ter1-16T are sensitive to RsaI and resistant to MseI, and second, 2D gel electrophoresis of TRFs derived from ter1-16T revealed an arc of telomeric signal migrating in a pattern consistent with double-stranded DNA circles. We therefore conclude the looped and circular molecules observed here are bona fide t-loops and t-circles.

Several lines of evidence have led to the hypothesis that t-circles form from a recombination reaction involving t-loops. RAD52-dependent telomere rapid deletion (TRD) of overly elongated S. cerevisiae telomeres occurs via intramolecular recombination that is proposed to involve a t-loop intermediate (2, 21). Sudden telomere shortening in mammalian cells following TRF2ΔB expression was dependent upon the recombination proteins XRCC3 and NBS1 and was accompanied by the formation of t-circles (36). t-circle formation in mice following POT1A deletion is also NBS1 dependent (38). In human ALT cells, t-circles have a size distribution similar to that of the loop portions of t-loops, suggesting they are derived from the same source (4), and t-circles were repressed in ALT cells following NBS1 and XRCC3 inhibition via RNA interference (9).

The data presented in this report strongly support the idea that t-circle formation in K. lactis is dependent on both recombination and t-loops. Not only are the frequencies of t-loops and t-circles in ter1-16T cells greatly diminished in the absence of RAD52, but the sizes of t-circles also correlate with the sizes of the loop portions of t-loops. Additionally, the small number of RAD52-independent t-loops and t-circles we observed could also be related to TRD, as a subset of TRD events were previously shown not to require RAD52 (2). One implication of our link between t-loops and t-circles is that both the formation and the resolution of t-loops are likely to be critical steps in any RTE that is driven by t-circles. A second implication is that t-loops occur in any of the budding yeasts or mutants in which t-circles have been observed (18, 19). As the resolution of t-loop junctions by homologous recombination is predicted to generate t-circles that have a nick or gap on both strands, this may explain why psoralen appears to stabilize t-circles in our preparations, as well as the exclusively open circular form of t-circles observed in this study.

When RAP1 is overexpressed in ter1-16T cells, there is a sharp decrease in the incidence of both t-loops and t-circles. This, however, does not indicate that t-loops are solely associated with an uncapped-telomere phenotype in K. lactis, as the very long overhangs present at ter1-16T telomeres are expected to greatly improve the efficiency of psoralen cross-linking within the t-loop junction. Therefore, even if the short overhangs of wild-type and ter1-16T RAP1OE K. lactis cells are sequestered within t-loops, our isolation protocol might be poorly able to cross-link these structures and recover them intact. Thus, while we cannot assign an architecture to wild-type K. lactis telomeres, we can conclude that in ter1-16T RAP1OE the telomeres are structurally arranged in a way that prohibits excessive strand invasion at a t-loop junction, leading to a diminished recovery of t-loops or t-circles. We propose that poor occupancy of Rap1 protein at the mutant telomeric repeats present in ter1-16T cells leads to an altered telomere structure that renders the telomeres more recombinogenic, including a greater amount of strand invasion at the t-loop junction (Fig. 7). Strand invasion of a telomeric end under the recombinogenic state of telomeres lacking Rap1 would be prone to some or all of the processes that might act on a strand-invaded broken DNA end that has formed a D-loop, including branch migration at the t-loop junction, nucleolytic cleavage resulting in TRD and a free t-circle, or extension by a DNA polymerase.

FIG. 7.

Model for t-loop formation in ter1-16T. Under conditions of normal Rap1 binding, the telomeres have short 3′ overhangs and are protected from recombination. It remains unknown if wild-type telomeres are arranged into a t-loop or some other structural form. A defect in the ability of the ter1-16T mutant repeats to bind to Rap1 leads to extended 3′ overhangs at telomeres, which become prone to recombination, leading to extensive strand invasion of the elongated overhangs in t-loops and a greater experimental recovery. In the figure, the strand-invaded region is shown relatively enlarged for clarity. Recombinational resolution of this t-loop may produce different outcomes, including a shortened telomere and a t-circle. This model does not exclude the possibility that wild-type telomeres form t-loops that are resistant to recombinational processes.

Acknowledgments

Roger R. Reddel (CMRI, Westmead, Australia) is thanked for the use of his laboratory's apparatus and reagents to complete some of the 2D gels shown here.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to J.D.G. (GM31819 and ES 013773) and to M.J.M. (GM61645). C.G.-V. was supported through a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (5T32GMOO&10330) and S.A.C. though a National Institutes of Heath postdoctoral training grant (GM077900-01).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiard, S., M. Doudeau, S. Pinte, A. Poulet, C. Lenain, C. Faivre-Moskalenko, D. Angelov, N. Hug, A. Vindigni, P. Bouvet, J. Paoletti, E. Gilson, and M. J. Giraud-Panis. 2007. A topological mechanism for TRF2-enhanced strand invasion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bucholc, M., Y. Park, and A. J. Lustig. 2001. Intrachromatid excision of telomeric DNA as a mechanism for telomere size control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 216559-6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celli, G. B., and T. de Lange. 2005. DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion. Nat. Cell Biol. 7712-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesare, A. J., and J. D. Griffith. 2004. Telomeric DNA in ALT cells is characterized by free telomeric circles and heterogeneous T-loops. Mol. Cell. Biol. 249948-9957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cesare, A. J., N. Quinney, S. Willcox, D. Subramanian, and J. D. Griffith. 2003. Telomere looping in P. sativum (common garden pea). Plant J. 36271-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chase, J. W., R. F. Whittier, J. Auerbach, A. Sancar, and W. D. Rupp. 1980. Amplification of single-strand DNA binding protein in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 83215-3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, Q., A. Ijpma, and C. W. Greider. 2001. Two survivor pathways that allow growth in the absence of telomerase are generated by distinct telomere recombination events. Mol. Cell. Biol. 211819-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole, R. S. 1970. Light-induced cross-linking of DNA in the presence of a furocoumarin (psoralen). Studies with phage lambda, Escherichia coli, and mouse leukemia cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 21730-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton, S. A., J. H. Choi, A. J. Cesare, S. Ozgur, and J. D. Griffith. 2007. Xrcc3 and Nbs1 are required for the production of extrachromosomal telomeric circles in human alternative lengthening of telomere cells. Cancer Res. 671513-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Bruin, D., S. M. Kantrow, R. A. Liberatore, and V. A. Zakian. 2000. Telomere folding is required for the stable maintenance of telomere position effects in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 207991-8000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Bruin, D., Z. Zaman, R. A. Liberatore, and M. Ptashne. 2001. Telomere looping permits gene activation by a downstream UAS in yeast. Nature 409109-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreira, M. G., K. M. Miller, and J. P. Cooper. 2004. Indecent exposure. When telomeres become uncapped. Mol. Cell 137-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith, J. D., and G. Christiansen. 1978. Electron microscope visualization of chromatin and other DNA-protein complexes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 719-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith, J. D., L. Comeau, S. Rosenfield, R. M. Stansel, A. Bianchi, H. Moss, and T. de Lange. 1999. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell 97503-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groff-Vindman, C., A. J. Cesare, S. Natarajan, J. D. Griffith, and M. J. McEachern. 2005. Recombination at long mutant telomeres produces tiny single- and double-stranded telomeric circles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 254406-4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henson, J. D., A. A. Neumann, T. R. Yeager, and R. R. Reddel. 2002. Alternative lengthening of telomeres in mammalian cells. Oncogene 21598-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, Y. J., C. H. Shen, and D. J. Clark. 2004. Purification and nucleosome mapping analysis of native yeast plasmid chromatin. Methods 3359-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larrivee, M., and R. J. Wellinger. 2006. Telomerase- and capping-independent yeast survivors with alternate telomere states. Nat. Cell Biol. 8741-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin, C. Y., H. H. Chang, K. J. Wu, S. F. Tseng, C. C. Lin, C. P. Lin, and S. C. Teng. 2005. Extrachromosomal telomeric circles contribute to Rad52-, Rad50-, and polymerase delta-mediated telomere-telomere recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 4327-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundblad, V., and E. H. Blackburn. 1993. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1− senescence. Cell 73347-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lustig, A. J. 2003. Clues to catastrophic telomere loss in mammals from yeast telomere rapid deletion. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4916-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McEachern, M. J., and E. H. Blackburn. 1996. Cap-prevented recombination between terminal telomeric repeat arrays (telomere CPR) maintains telomeres in Kluyveromyces lactis lacking telomerase. Genes Dev. 101822-1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEachern, M. J., and J. E. Haber. 2006. Break-induced replication and recombinational telomere elongation in yeast. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75111-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murti, K. G., and D. M. Prescott. 1999. Telomeres of polytene chromosomes in a ciliated protozoan terminate in duplex DNA loops. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9614436-14439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natarajan, S., C. Groff-Vindman, and M. J. McEachern. 2003. Factors influencing the recombinational expansion and spread of telomeric tandem arrays in Kluyveromyces lactis. Eukaryot. Cell 21115-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natarajan, S., and M. J. McEachern. 2002. Recombinational telomere elongation promoted by DNA circles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 224512-4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikitina, T., and C. L. Woodcock. 2004. Closed chromatin loops at the ends of chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 166161-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nosek, J., A. Rycovska, A. M. Makhov, J. D. Griffith, and L. Tomaska. 2005. Amplification of telomeric arrays via rolling-circle mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 28010840-10845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stansel, R. M., T. de Lange, and J. D. Griffith. 2001. T-loop assembly in vitro involves binding of TRF2 near the 3′ telomeric overhang. EMBO J. 205532-5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teng, S. C., and V. A. Zakian. 1999. Telomere-telomere recombination is an efficient bypass pathway for telomere maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 198083-8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomaska, L., J. Nosek, A. M. Makhov, A. Pastorakova, and J. D. Griffith. 2000. Extragenomic double-stranded DNA circles in yeast with linear mitochondrial genomes: potential involvement in telomere maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 284479-4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomaska, L., S. Willcox, J. Slezakova, J. Nosek, and J. D. Griffith. 2004. Taz1 binding to a fission yeast model telomere: formation of t-loops and higher order structures. J. Biol. Chem. 27950764-50772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Topcu, Z., K. Nickles, C. Davis, and M. J. McEachern. 2005. Abrupt disruption of capping and a single source for recombinationally elongated telomeres in Kluyveromyces lactis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1023348-3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Underwood, D. H., C. Carroll, and M. J. McEachern. 2004. Genetic dissection of the Kluyveromyces lactis telomere and evidence for telomere capping defects in TER1 mutants with long telomeres. Eukaryot. Cell 3369-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Steensel, B., A. Smogorzewska, and T. de Lange. 1998. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell 92401-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, R. C., A. Smogorzewska, and T. de Lange. 2004. Homologous recombination generates T-loop-sized deletions at human telomeres. Cell 119355-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wray, L. V., Jr., M. M. Witte, R. C. Dickson, and M. I. Riley. 1987. Characterization of a positive regulatory gene, LAC9, that controls induction of the lactose-galactose regulon of Kluyveromyces lactis: structural and functional relationships to GAL4 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 71111-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, L., A. S. Multani, H. He, W. Cosme-Blanco, Y. Deng, J. M. Deng, O. Bachilo, S. Pathak, H. Tahara, S. M. Bailey, Y. Deng, R. R. Behringer, and S. Chang. 2006. Pot1 deficiency initiates DNA damage checkpoint activation and aberrant homologous recombination at telomeres. Cell 12649-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zellinger, B., S. Akimcheva, J. Puizina, M. Schirato, and K. Riha. 2007. Ku suppresses formation of telomeric circles and alternative telomere lengthening in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 27163-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]