Abstract

Tcfap2a, the gene encoding the mouse AP-2α transcription factor, is required for normal development of multiple structures during embryogenesis, including the face and limbs. Using comparative sequence analysis and transgenic-mouse experiments we have identified an intronic enhancer within this gene that directs expression to the face and limb mesenchyme. There are two conserved sequence blocks within this intron, and the larger of these directs tissue-specific activity and is found in all vertebrate Tcfap2a genes analyzed. To assess the role of the enhancer in regulating endogenous mouse Tcfap2a expression, we have deleted this cis-regulatory sequence from the genome. Loss of this element severely impairs Tcfap2a expression in the limb bud mesenchyme but generates only a modest reduction in the facial mesenchyme. The reduction in Tcfap2a transcription is accompanied by altered patterning of the forelimb, resulting in postaxial polydactyly. These results indicate that the major role for this enhancer resides within the limb bud, and it serves to maintain a level of Tcfap2a expression that limits the size of the hand plate and the associated number of digit primordia. The potential role of this cis-acting sequence in modeling the size and shape of the face and limbs during evolution is discussed.

The appropriate development of a multicellular organism requires the interplay of numerous regulatory transcription factors with an array of cis-acting sequences associated with gene-specific promoter and enhancer elements. The arrangement of specific cis-acting DNA elements in the genome has a profound influence on the pattern of gene expression. Ultimately, the alteration and shuffling of the cis-acting sequences associated with critical developmental regulatory genes are believed to be a major driver of evolutionary diversity (28, 30). For this reason, the presence of a highly conserved regulatory element linked with an orthologous gene in diverse species is often thought to indicate the functional equivalence of these sequences, as well as to presage their developmental importance (2, 27, 36, 38, 41).

The AP-2 gene family encodes transcription factors that are required for development and function of multiple critical structures in both vertebrate and invertebrate species. Five AP-2 genes occur in the human and mouse genomes, Tcfap2a, Tcfap2b, Tcfap2c, Tcfap2d, and Tcfap2e, encoding the proteins AP-2α, -β, -γ, -δ, and -ɛ, respectively (13). Tcfap2a is particularly relevant for the study of conserved developmental function across species, especially regarding the head and limbs. A null mutation of this gene in either mice or zebrafish results in severe craniofacial defects, hypoplasia of the neural crest-derived skeletal elements, and facial clefting (14, 16, 31, 43). In addition, the human gene, TFAP2A, is located at 6p24 in a region that has chromosomal translocations and deletions associated with facial clefting (9-11, 35). The Drosophila melanogaster genome contains one AP-2 family member, and mutation of this gene also gives rise to defects in formation of the head (15, 22). Limb development is also affected by loss of either the Drosophila AP-2 gene or mouse Tcfap2a (15, 22, 31, 43). The majority of Tcfap2a null mice exhibit forelimb defects, typified by loss of the radius, and chimeras composed of a mixture of wild-type and Tcfap2a-null cells display a range of limb defects (26, 31, 43). We have begun a study of the cis-acting sequences required for mammalian Tcfap2a expression using transgenic-mouse analysis to understand the regulatory hierarchy responsible for this gene's expression during embryogenesis. These studies have identified a cis-regulatory region located in the fifth introns of the human and mouse genes that drives expression to the mesenchyme of the frontonasal process and the limb buds (12, 44). We have identified several transcription factor recognition sites within this enhancer element and further demonstrated that a STAT binding site is required for robust expression in the face and limbs (12). Here, we have extended these studies by isolating the equivalent enhancer element from other vertebrate species and testing it in the transgenic-mouse assay. We also directly test the importance of this element for AP-2α expression and function by deleting it from the mouse genome using gene targeting technology. Together, these studies assess the relationship between sequence conservation and functional relevance for this enhancer element and provide insight into the importance of AP-2α's mesenchymal expression domain for its overall function in limb and face development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of promoter and enhancer fragments and construction of transgenes.

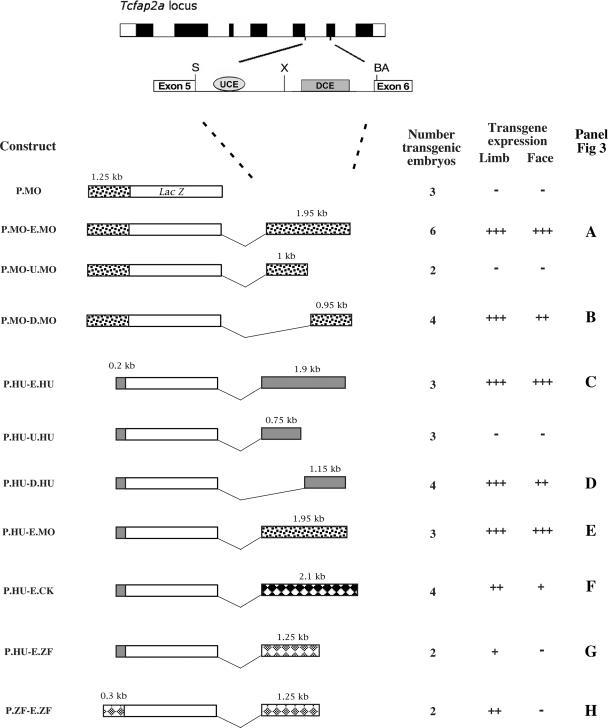

Standard cloning procedures were utilized to generate a series of LacZ reporter plasmids, and all relevant products were sequenced at the Keck Foundation sequencing facility (Yale University). We used the following nomenclature for the constructs: P, promoter; E, intact fifth intron enhancer; U, upstream portion of intronic enhancer; D, downstream portion of intronic enhancer; MO, mouse; HU, human; CK, chick; ZF, zebrafish. Plasmid P.MO (CM 1.25 BglII LZ; see Fig. 2, P.MO) is the basic mouse Tcfap2a promoter LacZ expression construct. It contains 1.25 kb of Tcfap2a promoter sequence with essential octamer and initiator elements (8), followed by an ∼270-nucleotide (nt) 5′ noncoding region, the translational start site, and the first 13 amino acids of AP-2α fused in frame to the LacZ coding region of the plasmid pLZFSV (3). The P.MO construct failed to produce any tissue-specific β-galactosidase activity when utilized to make transgenic mice, in agreement with related studies which employed the basic promoter of the human gene (44). The plasmid P.MO-E.MO (N4-1) was generated by inserting a 1.95-kb SpeI-BsaAI fragment of Tcfap2a downstream of the LacZ gene in a 3′ polylinker. This downstream fragment contains 11 bp of exon 5, the entire 1,935-bp fifth intron, and 35 bp of exon 6. An XhoI site in the middle of the intron sequence was then used to generate the subclones P.MO-U.MO (DNL4) and P.MO-D.MO (DNL5), which contain an ∼1-kb SpeI-XhoI upstream fragment or a 0.95-kb XhoI-BsaAI downstream portion of the intron, respectively (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Transgenic analysis of the Tcfap2a FNP/limb bud mesenchyme (LBM) enhancer. (Top) Schematic representation of the Tcfap2a locus with exons depicted as filled boxes. Intron 5 is expanded to highlight two subregions of high sequence conservation, the UCE and the DCE. Abbreviations: S, SpeI; X, XhoI; BA, BsaAI. (Bottom left) Schematic representation of the transgenic constructs utilized in these studies and the associated expression data. Each construct contains basal promoter elements that direct the expression of the Tcfap2a-LacZ fusion transgene. Promoter and enhancer sequences are shown for mice, (dotted rectangles), humans (gray rectangles), chicks (black diamonds), and zebrafish (gray diamonds). The sizes of the fragments are indicated above the rectangles. (Bottom right) Summary of expression data acquired from each transgene. The number of transgenic embryos is indicated for each construct. For constructs such as P.MO that did not yield expression in the face and limbs, this number refers to the number of LacZ-positive embryos obtained in which we saw random and inconsistent patterns of β-galactosidase expression between transgenic embryos. For constructs such as P.MO-E.MO that were expressed in the face and limbs, this number indicates all the transgenic embryos that were obtained and indicates that the locations of β-galactosidase expression were relatively consistent between all embryos. Expression was scored in LBM (limb) and FNP (face). Relative intensity and domain of expression are indicated by the number of plus signs, while a minus sign indicates that no expression was observed in the transgenic embryos. The right column indicates the relevant panel showing a representative expression pattern for the particular construct in Fig. 3.

The derivation of the basic human promoter construct C1 Xho βgal and the derivative containing the human fifth intron, P.HU-E.HU (SN48), has been described previously (44). The latter construct utilizes SpeI and BsaAI sites in exons 5 and 6, respectively, which are located at identical positions to those in the mouse construct. The P.HU-U.HU (SC48) and P.HU-D.HU (SC44) subclones were made using an AvrII site present in the human fifth intron and contain, respectively, the upstream SpeI-AvrII fragment or the downstream AvrII-BsaAI fragment. The human promoter construct C1 Xho βgal was also used in combination with the mouse fifth intron enhancer fragment to generate the plasmid P.HU-E.MO (N2-1).

The chicken 2.1-kb fifth intron enhancer sequence was derived from White Leghorn genomic DNA and then combined with the human promoter construct C1 Xho βgal to yield plasmid P.HU-E.CK (J25 CKU). Zebrafish sequences, derived from a bacterial artificial chromosome clone containing Tcfap2a (Genome Systems, Inc.), were utilized to generate LacZ constructs in which the zebrafish enhancer was combined with the human (P.HU-E.ZF) or zebrafish (P.ZF-E.ZF) promoter. For further details on fragment derivation and cloning, see the supplemental material. Sequence alignments were performed using the MacVector software package (Accelrys Inc.).

Generation and staining of transgenic mouse embryos.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center or Yale University Animal Care and Usage Committees. Transgenic FVB mice were generated by standard methods (24). Prior to microinjection, vector and insert sequences were separated by treatment with appropriate restriction enzymes, followed by sucrose density centrifugation. The fragments corresponding to the LacZ transgenes were dialyzed extensively against 10 mM Tris-Cl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5. Transgenic mice were generated by microinjecting DNA into pronuclei of fertilized oocytes of inbred FVB mice (Taconic). The embryos surviving the microinjection were transferred into oviducts of pseudopregnant CD-1 fosters (Charles River). The concentration of DNA used in the microinjection was adjusted to 1 to 5 μg/ml based on the lengths of the constructs. Embryos were collected from foster females (CD-1) at embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5), with the day of the transgenic manipulation being scored E0.5. The actual developmental stage of the embryos varied due to ex vivo manipulation (24). Embryos were stained for β-galactosidase activity by standard procedures (24), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and photographed. Staining was standardized to 18 h to facilitate a direct comparison of expression levels among the different transgenes.

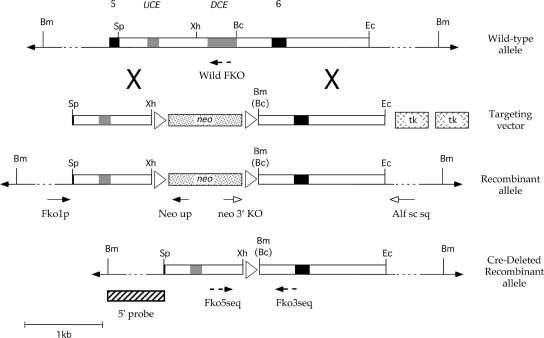

Generation of Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice.

The targeting construct utilized sequences derived from a previously characterized 129/Sv Tcfap2a genomic clone (43). The 5′ region of homology corresponded to a 1-kb SpeI-XhoI fragment containing 11 nt of exon 5 and the upstream half of the fifth intron. The 3′ region of homology extended ∼1.65 kb from a BclI site positioned downstream of the distal conserved element (DCE) in the fifth intron (see Fig. 1 and 4) to an Eco47III site in the sixth intron. These two regions of homology were separated by a floxed version of the neomycin resistance gene from the plasmid pMC1 neo polyA (Stratagene). Subsequently, two herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase expression cassettes were placed downstream of the Tcfap2a sequences to generate the final targeting vector (see Fig. 4). The integrity of the targeting construct was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. Following linearization with NotI, 25 μg of the construct was electroporated into CJ-7 embryonic stem (ES) cells (gift from Thomas Gridley). A total of 212 G418-resistant colonies were screened by PCR analysis (see the supplemental material) for the correct targeting event. One positive clone was identified based upon the presence of the expected 1.4-kb and 1.7-kb products in the 5′ and 3′ PCRs, respectively, and this clone also possessed a euploid karyotype. Next, to remove the neo gene from the genomic locus, the positive ES cell clone was electroporated with a β-actin Cre recombinase expression vector. Subsequently, 215 single-cell clones were cultured either in the presence or absence of G418. A total of 20 clones were G418 sensitive, and these were then screened for the Cre recombinase-mediated loss of the neomycin resistance gene by PCR analysis. The expected product of 350 nt was observed in 14 clones. Three of these clones were karyotyped and found to be euploid, and the PCR products were also sequenced to confirm the replacement of the DCE by a LoxP site. One of these clones (214) was subsequently injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. The resulting chimeric adult male animals were then bred to outbred Black Swiss mice (Taconic) to derive heterozygous Tcfap2aDCE+/− offspring. The targeted mutation has been maintained through backcrossing with outbred Black Swiss mice.

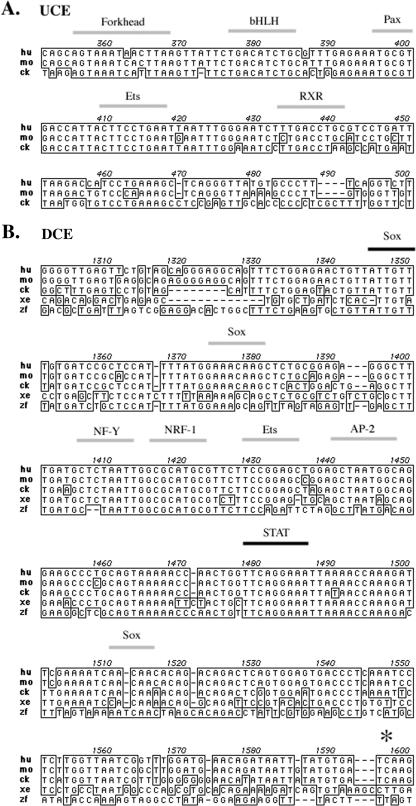

FIG. 1.

Two conserved sequence blocks occur within the Tcfap2a fifth intron of vertebrates. Shown are sequence alignments of (A) the UCE and (B) the DCE. Identical sequences are boxed, and gaps are indicated by dashes. Numbers above the alignment refer to the positions in the human genomic intron relative to the splice donor of exon 5. Thick gray lines above the sequence indicate the predicted binding sites for the associated transcription factor based on computer prediction programs or experimental analysis (6, 12, 21, 37). Thick black lines indicate the positions of a Sox site and the conserved STAT binding site that is critical for enhancer activity (12). The asterisk in panel B shows the position of a BclI site in the mouse genome that marks the downstream extent of the DCE sequences deleted (see Fig. 4). hu, human; mo, mouse; ck, chicken; xe, frog; zf, zebrafish. bHLH, basic helix-loop-helix; RXR, retinoid X receptor.

FIG. 4.

Derivation of the Tcfap2aDCE−/− allele. Diagrammatic representations of, from top to bottom, wild-type mouse Tcfap2a (top), targeting vector, recombinant locus, and the final DCE-deleted allele after removal of the neo gene with Cre recombinase are shown. Exons 5 and 6 (black boxes), the UCE and DCE (gray boxes), restriction enzyme sites (Bc, BclI; Bm, BamHI; Ec, Eco47III; Sp, SpeI; Xh, XhoI), loxP sites (white triangles) are shown along with neomycin resistance (neo) and thymidine kinase (tk) genes. Note that a novel BamHI site replaces the BclI site, denoted by Bc, located at the 3′ end of the DCE after gene targeting. The positions of the primer pairs used for PCR amplification and genotyping (arrows) and the 5′ probe used for Southern blotting analysis (striped box) are also shown.

For genotyping of adult or embryonic mice, DNA from embryo tissue and adult tail samples was prepared using the DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN) and analyzed by PCR or Southern blot analysis (see the supplemental material). The generation and genotype analysis of mice heterozygous for the Tcfap2a LacZ knock-in allele (AP-2αki) have been described previously (5).

Whole-mount immunohistochemistry, analysis of tissue sections and skeletal staining.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) was performed essentially as described previously (40) using the AP-2α cDNA plasmid TRIP1 (42). The plasmid was digested with HindIII, and then an antisense probe was transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of digoxigenin-UTP, using conditions described by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). For cryosectioning, embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek), and then sectioned at 20 μM and stored at −70°C. Hybridization, washing, and detection utilized the same protocols and probes as for whole-mount analysis. Subsequently, the slides were counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and then dehydrated, cleared, mounted, and stored at room temperature. Skeletal staining of 18.5-day-postcoitus embryos, neonates, and adults with alcian blue and alizarin red was performed as described previously (18).

RESULTS

A conserved enhancer element for face and limb expression occurs in the Tcfap2a fifth intron.

We had previously determined that the human and mouse genes encoding AP-2α contained an enhancer element within the ∼2-kb fifth intron that could direct expression of a linked LacZ transgene to the developing frontonasal prominence (FNP) and limb bud mesenchyme during mouse embryogenesis (12, 44). The location of an enhancer element between two coding exons provided defined genomic landmarks that could be used to isolate and analyze the equivalent intronic region of Tcfap2a from other species to ascertain if there was a high degree of sequence conservation in this region. Alignment of the genomic sequences for the human, mouse, chick, frog, and zebrafish genes indicated that the location of this intron was conserved in these vertebrate species. Sequence comparison of this intronic region revealed two highly conserved sequence elements (Fig. 1). The more 5′ of these sequences, the upstream conserved element (UCE), spanned ∼150 bp and was recognizable only in humans, mice, and chickens (Fig. 1A). The UCE sequences from humans and mice were 88% homologous, and those from humans and chickens were 75% homologous. No equivalent region could be identified in the frog or zebrafish intron, and these two species had no alternative region of homology in the same location. The DCE is more extensive, spanning ∼300 bp (Fig. 1B). Across this entire region, the sequence is conserved 96% from humans to mice, 88% from humans to chicks, and 65% from humans to zebrafish. In the 100-nt core region of the DCE, the extent of homology is even more significant: 98% from humans to mice, 97% from humans to chicks, and 85% from humans to zebrafish. The UCE and DCE both contain conserved elements that are the predicted binding sites for important transcription factors (Fig. 1), but with the exception of the Stat and Sox sites in the DCE these associations have not been confirmed experimentally (12).

Transgenic analysis of the fifth intron demonstrates the importance of the DCE for tissue-specific expression in the face and limbs.

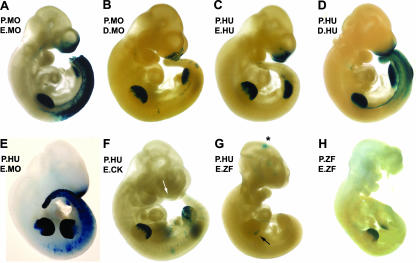

The bipartite nature of the conserved sequence blocks present within this intronic region prompted us to examine if they represented independent or cooperating cis-acting elements in the context of the human and mouse enhancers. Initial transgenic studies focused on the mouse gene. The basic mouse promoter construct, P.MO, is not active in the transgenic assay, but when combined with the fifth intron enhancer sequence in the P.MO-E.MO construct it is capable of driving robust LacZ expression in both the faces and limbs of transgenic mice at E10.5 (Fig. 2 and 3A). These findings are comparable to those obtained with the human construct (44) (Fig. 2 and 3C, P.HU-E.HU), demonstrating that the equivalent intronic regions of both the mouse and human genes contain cis-acting sequences specific for limb and FNP mesenchyme expression. We next divided the fifth intron of the mouse gene into upstream and downstream portions and tested them in the transient transgenic assay in combination with the mouse promoter. The upstream region of the intron failed to generate specific LacZ expression (Fig. 2, P.MO-U.MO). In contrast, the downstream fragment of the mouse intron (P.MO-D.MO) was able to direct expression to the face and limbs (Fig. 2 and 3B). Similar results were obtained using the transgenes based on the human enhancer and promoter sequences. The upstream region containing the UCE was not active (Fig. 2, P.HU-U.HU), whereas the downstream part with the DCE was active in driving face and limb expression (Fig. 2 and 3D, P.HU-D.HU).

FIG. 3.

Expression of β-galactosidase in transgenic embryos. (A) Lateral views of E10.5 transgenic embryos generated using P.MO-E.MO (A), P.MO-D.MO (B), P.HU-E.HU (C), P.HU-D.HU (D), P.HU-E.MO (E), P.HU-E.CK (F), P.HU-E.ZF (G), and P.ZF-E.ZF (H). Embryos in panels A to E show strong expression in the face and limbs. Panels A, D, and E are examples of embryos with a strong trunk neural crest expression domain. The arrow in panel F shows the limited facial expression domain. The arrow in panel G shows the posterior limb bud expression domain. The asterisk indicates a region of LacZ expression in the central nervous system that was not consistently observed with this transgene. The embryo in panel H was broken prior to photography, but no facial expression was noted in the undamaged intact embryo.

Therefore, although there are two blocks of conserved sequence within the fifth introns of the human and mouse genes, the major tissue-specific activity resides in the 3′ half of the intron housing the DCE. The UCE region was not capable of directing tissue-specific activity in isolation, but we did note that the overall expression levels appeared lower when this region was absent compared to those for the intact intron, particularly for the face region. Given this finding, we hypothesize that the upstream region may contain cis-acting sequences that augment face and limb expression driven by the downstream portion.

The examination of the fifth intron in the other vertebrates indicated that the UCE was apparent only in mammals and avians, while the DCE was recognizable in all vertebrates analyzed. Since the DCE region was the major driver of tissue-specific expression in the transgenic assays, we next tested if combinations of promoter and enhancer sequences from diverse species could direct similar expression in the transient mouse embryo assay. First, the mouse intronic enhancer was tested in combination with the minimal human promoter (P.HU-E.MO; Fig. 3E), and this construct generated a pattern of expression similar to that for the cognate human and mouse transgenes in the face and limbs. Note that there were differences in the potentials of the intact mouse and human enhancer fragments to direct expression to the trunk neural crest, which is also a site of endogenous Tcfap2a expression (20). The intact mouse intron was capable of driving robust trunk neural crest expression in the majority of transgenic mice analyzed. In contrast, the corresponding full-length human construct, P.HU-E.HU, did not (Fig. 3, compare panels A and E with C) although a shorter version of the human intron lacking the UCE could produce expression in trunk neural crest cells (NCC) (P.HU-D.HU; Fig. 3D). These findings indicate that there are species-specific differences between the mouse and human enhancers with respect to the trunk neural crest, but, since the levels of expression driven by the human and mouse enhancers were more consistent for the limbs and face, the NCC aspect of the pattern was not pursued further.

Next, the human promoter was tested in combination with the fifth intron from the chicken and zebrafish genomes, which possess or lack the UCE, respectively. The human promoter-chicken enhancer combination (P-HU-E.CK; Fig. 3F) yielded strong expression in the limb bud but only very weak expression in the FNP. When the zebrafish enhancer was utilized in concert with the human promoter (P.HU-E.ZF; Fig. 3G), limb expression was weaker still and confined to the more posterior aspects of the limb bud. Facial expression was not visualized in this context. The possibility that the zebrafish enhancer functions preferentially with its cognate promoter was also assessed (P.ZF-E.ZF; Fig. 3H), and this combination produced readily detectable expression in the distal limb bud mesenchyme but again failed to drive detectable LacZ activity in the face. These data indicate that the zebrafish promoter-enhancer combination works slightly better together than the cross-species human-zebrafish combination, possibly due to the additional 100 bp of nonconserved zebrafish promoter sequence present in P.ZF-E.ZF. However, the most striking observation is that both constructs containing the zebrafish enhancer can produce limb expression but do not yield β-galactosidase activity in the face. Together, these data indicate that cis-regulatory sequences capable of directing expression in the mouse limb are conserved within the fifth intron of Tcfap2a from zebrafish to humans. In contrast, the facial mesenchyme-specific activity of this region is more limited to the mammalian species tested, although the chicken intron can also produce very limited activity within the face.

Generation of mice lacking the Tcfap2a DCE.

Given that the sequence and activity of the Tcfap2a fifth intron are conserved between species, we next hypothesized that this region might serve an important regulatory role in vivo, especially since Tcfap2a can regulate both face and limb development in the mouse, chicken, and zebrafish model systems (4, 14, 16, 25, 26, 31, 32, 43). Therefore, a genetically altered mouse model system was developed in which the DCE was deleted to test the importance of this cis-acting sequence for endogenous Tcfap2a expression and function in vivo. The DCE was targeted rather than the entire fifth intron to limit any impact on splicing that might impact global AP-2α levels in the developing embryo and because the DCE was the most critical region with respect to expression in the transgenic analysis. The strategy employed to target and delete the DCE is shown in Fig. 4. The initial gene targeting event replaced an ∼530-nt region of the fifth intron containing the entire DCE with a floxed neomycin resistance gene. ES cells containing the correct homologous recombination event were then transfected with a Cre recombinase expression construct and selected for loss of G418 resistance. ES cells in which the DCE region had been replaced with a single loxP site were injected into host mouse blastocysts and used to generate chimeras, and these were bred to obtain transmission of the modified Tcfap2a allele, Tcfap2aDCE−. Heterozygous Tcfap2aDCE+/− mice were viable and fertile and did not display any gross developmental abnormalities (data not shown). Heterozygous Tcfap2aDCE+/− mice were then bred together and the genotypes of the offspring determined by both PCR and Southern blot analysis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Mendelian ratios of homozygous mice lacking the DCE were found throughout embryogenesis.

Tissue-specific alterations in Tcfap2a expression in mice lacking the Tcfap2a DCE.

Next, the effect of DCE enhancer loss with respect to Tcfap2a expression in the embryonic face and limbs was examined. WMISH performed on E10.5 mice indicated that the levels of Tcfap2a transcripts in homozygous Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice in the forelimb and hind limb buds were considerably lower than those in a wild-type control (Fig. 5). The more anterior and medial expression domains in the limb buds were essentially abolished, and transcripts were present only in a posterior domain that was more limited than the equivalent region in the wild-type controls (Fig. 5A, B, and C). Expression in the mesenchyme of the medial and lateral nasal prominences also appeared lower (Fig. 5A and D). However, these interpretations were complicated because Tcfap2a is normally expressed at significant levels in the surface ectoderm during mouse embryogenesis and the removal of the DCE should not influence this surface expression domain, i.e., Tcfap2a should still be expressed at similar levels in the surface ectoderms of both wild-type and mutant embryos, and this might mask underlying changes in the mesenchyme. Therefore, expression in sectioned material of both the limbs and face was examined. These analyses demonstrated that Tcfap2a expression still occurred in the surface ectoderms of the limbs and faces of Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice at levels similar to those for wild-type controls (Fig. 6). Expression in the mesenchyme of the forelimb and hind limb buds was almost completely abolished compared to that for wild-type controls, in agreement with the WMISH data (Fig. 6A and B). In contrast, expression in the facial mesenchyme was still readily apparent, although clearly reduced in intensity compared to that for a wild-type control (Fig. 6C and D). The in situ hybridization analysis was extended to both earlier and later embryonic time points to determine if the loss of the DCE altered the initiation or maintenance of Tcfap2a expression in the face and limbs. Data from these studies indicated that the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice showed similar reductions in Tcfap2a expression in the face and limbs at all time points tested and that there was no major difference in the onset or maintenance of expression (data not shown). Examination of data from WMISH and sectioned material showed that the levels of Tcfap2a expression were similar to those in wild-type control samples in other regions of the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse embryos including the brain, spinal cord, dorsal root ganglia, eye, and branchial arches (Fig. 5). To obtain a more quantitative assessment of the differences in AP-2α expression between wild-type and Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice, we employed quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (Q RT-PCR) for an analysis of transcript levels in the FNP, the forelimb, and the tail spinal cord. Data from this analysis indicated that expression of AP-2α in the forelimb was down to ∼40% of wild-type levels, whereas levels of expression in the face in the mutant and control samples were similar (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). However, we note that AP-2α expression in the ectoderm was not affected by deletion of the DCE (Fig. 6) and presumably accounted for a significant amount of the Q RT-PCR signal. Thus, our Q RT-PCR assessment of the extent of the reduction in AP-2α transcript levels in the mesenchyme of the face—and especially the limb—is likely to be an underestimate. Based on our in situ and Q RT-PCR findings we conclude that deletion of the DCE impacted expression mainly in the mesenchyme of the limbs and to a much lesser extent the mesenchyme of the face, as predicted from the transgenic analysis.

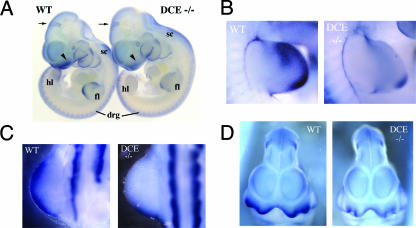

FIG. 5.

WMISH analysis of Tcfap2a expression in the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse. (A) Lateral views of E10.5 wild-type (WT) and Tcfap2aDCE−/− (DCE−/−) embryos stained with a Tcfap2a antisense probe. Arrowheads indicate the FNP, and arrows show domains of expression in the midbrain that are similar in the two embryos. Other regions of Tcfap2a expression that are similar in the two embryos are the trunk NCC-derived dorsal root ganglia (drg) and the spinal cord (sc). Reduced expression is apparent in the forelimb (fl) and hind limb (hl) buds of the Tcfap2aDCE−/− embryo. (B and C) Detailed lateral views of wild-type and Tcfap2aDCE−/− forelimb (B) and hind limb (C) buds. Anterior is to the top. (D) Ventral view of wild-type and Tcfap2aDCE−/− heads.

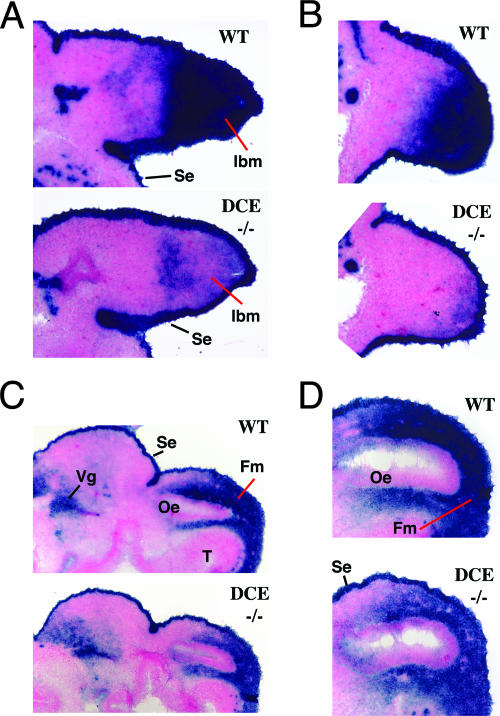

FIG. 6.

In situ analysis of Tcfap2a expression in the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse. All sections are stained following hybridization with a Tcfap2a antisense probe. (A and B) Sagittal sections of E10.5 wild-type (WT) and Tcfap2aDCE−/− (DCE−/−) forelimb (A) and hind limb (B) buds. Anterior is to the top. (C) Transverse sections of E10.5 wild-type and Tcfap2aDCE−/− heads. Dorsal is to the left. (D) Detailed view of transverse sections of E10.5 wild-type and Tcfap2aDCE−/− heads. Dorsal is to the left. In panels C and D, note that levels of expression within the surface ectoderms (se) and trigeminal ganglia (Vg) of the two embryos are similar, whereas the intensity of staining is lower in the facial mesenchyme (fm) of the Tcfap2aDCE−/− sample. Abbreviations: lbm, limb bud mesenchyme; oe, olfactory epithelium; t, telencephalon.

Mice lacking the Tcfap2a DCE exhibit limb defects.

Tcfap2aDCE−/− embryos were allowed to develop to term so that we could examine how the alterations in Tcfap2a expression impacted limb and face development. Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice were born at normal Mendelian ratios and were viable as well as fertile. The mice had normal face and head morphology at birth and during subsequent postnatal growth despite the reduction in Tcfap2a expression during development (Fig. 7A; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). In contrast, Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice invariably had an additional posterior forelimb digit that eventually developed a nail (Fig. 7). Tcfap2aDCE−/− hind limbs did not show an equivalent postaxial polydactyly despite the almost complete loss of Tcfap2a expression in the mesenchyme of these limbs. Examination of the underlying bone and cartilage indicated that the additional forelimb digit was the major skeletal patterning defect in the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice. Notably, the radius was present in all Tcfap2aDCE−/− forelimbs examined (Fig. 7C and data not shown) in contrast to the zeugopod defects observed in many Tcfap2a-null mice (31, 43). Transcript levels of Bmp4, Dkk1, Shh, Fgf4, Fgf8, and Hoxd family members were examined using WMISH to determine if changes in their expression correlated with the presence of an extra posterior forelimb digit. Expression of these various limb patterning genes was not noticeably altered in the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse limbs compared to that in wild-type littermates (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material; data not shown). Therefore, loss of Tcfap2a expression in the limb mesenchyme appears to induce an extra forelimb digit by mechanisms that do not involve gross changes in the expression of these key regulatory molecules.

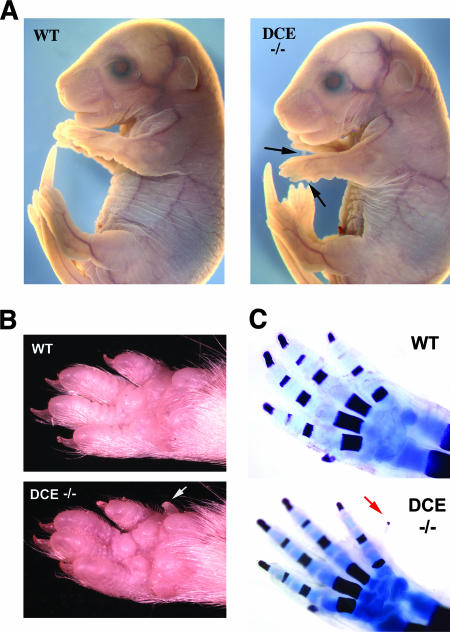

FIG. 7.

Face and limb morphology in the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse. (A) Gross morphology of E16.5 wild-type (WT) and Tcfap2aDCE−/− (DCE−/−) embryos. Both embryos have similar facial appearances, but the Tcfap2aDCE−/− forelimbs have an extra posterior digit nubbin (arrows). (B) Ventral view of forepaws of 6-week-old wild-type and Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice. The extra posterior digit and its associated nail are indicated (arrow). (C) Limb skeletons derived from E18.5 wild-type and Tcfap2aDCE−/− embryos. The extra posterior digit ossification center is shown with an arrow.

Finally, to determine if a further reduction in AP-2α levels would uncover more-severe defects in the face and limbs, offspring that contained the Tcfap2a LacZ knock-in allele in combination with the Tcfap2aDCE− allele were also generated. These mice showed a pattern of embryonic development indistinguishable from that shown by the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice and were also viable and fertile (data not shown). The implications of our combined results with respect to the tissue-specific requirements of Tcfap2a in face and limb development are discussed in detail below.

DISCUSSION

The AP-2α transcription factor is required for appropriate vertebrate embryogenesis. Loss or alteration of Tcfap2a expression or function results in a wide range of defects affecting development of the face, limb, eye, ear, neural tube, body wall, and heart outflow tract (1, 4, 5, 14, 16, 25, 26, 31, 39, 43). We have taken a two-pronged approach to identify the cis-regulatory sequences driving the spatiotemporal pattern of Tcfap2a transcription: functional transient transgenic analysis and a comparative sequence analysis to identify conserved elements. Both these analyses have highlighted the fifth intron of Tcfap2a as housing cis-regulatory sequences that direct Tcfap2a expression to the developing face and limbs—important targets of AP-2α activity.

A comparative sequence analysis of Tcfap2a organization in various vertebrate species indicates that the fifth intron UCE and DCE display by far the most extensive regions of conservation. The UCE is a 150-nt sequence that is present in all mammalian species analyzed. This element is conserved in birds and probably in reptiles based on an examination of trace archive sequences for Anolis carolinensis (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/tracemb.shtml). However, the UCE is not identifiable in the available amphibian and fish genomic DNA resources, and so selective pressure to maintain this conserved sequence block may have arisen only recently in the evolution of higher vertebrates. Analysis of both the mouse and human genes indicates that the portion of the intron containing the UCE does not direct tissue-specific expression in isolation but may augment the activity of the DCE. Thus, the primary function of the UCE may be to refine the pattern of Tcfap2a expression in the face and limbs in mammals, birds, and reptiles. In contrast the DCE—particularly the core sequences surrounding the NRF-1 and STAT sites—is highly conserved in mammals, birds, amphibians, and fish. In mouse transgenic assays, the mammalian DCE acts as a strong enhancer element directing expression in the mesenchyme of the face and limb buds, and even the chick and zebrafish enhancer elements are functional when introduced into the mouse, particularly with respect to the limbs.

The five human and mouse AP-2 genes appear to have arisen from a single ancestral gene (13, 19) and, with the exception of Tcfap2d, share common intron-exon boundaries with respect to the coding region. We therefore considered that the fifth introns of these other AP-2 genes could share sequences related to the Tcfap2a UCE and DCE, particularly since Tcfap2b is expressed in the facial mesenchyme (23) and Tcfap2c is expressed in the mesenchyme of both the limb and face (7). However, we were unable to identify any sequence homologies between the fifth intron of mouse Tcfap2a and the equivalent regions of the other AP-2 family members. One consequence of these findings is that the presence of a DCE within the fifth intron of a vertebrate AP-2 gene marks it as a Tcfap2a orthologue. Examination of invertebrate AP-2 gene family members reveals that this intron is either absent (D. melanogaster) or lacks sequence conservation with the vertebrate DCE or UCE (Ciona intestinalis and Caenorhabditis elegans). These findings indicate that the Tcfap2a DCE probably arose within the vertebrate lineage.

In the current analysis we found that the ability of the corresponding enhancers from humans, mice, chicks, and zebrafish to direct expression to the limb mesenchyme was particularly robust. The differential activities of the various enhancers with respect to the face and limbs indicate that the cis-acting sequences required for expression in these two tissues are not equivalent. The sequence changes between the human and chick enhancers have only a limited effect on limb expression in the mouse but greatly impact facial activity. Previous experiments focused on the mouse DCE also reveal that specific mutations within this regulatory region can also produce differential effects on face versus limb transgene expression (12). Taken together, the available data support a model in which the most homologous 100-nt core region of the DCE is most important for driving limb expression. This region contains a conserved STAT binding site that is critical for enhancer activity (12), as well as binding sites for other potential transcriptional regulators including NRF-1. Transgenic analysis of the mouse enhancer demonstrated that facial expression required additional sequences outside the core region of the DCE (12). The finding that these outlying sequences were more divergent between the various species examined presumably explains why expression in the face varied more dramatically in the cross-species mouse transgenic studies.

The loss of the DCE in the mouse genome did not have a general impact on the overall level of endogenous Tcfap2a expression, demonstrating that the DCE is not a generalized enhancer element for this gene. Instead, the DCE appeared to have a distinct tissue-specific function, and the deletion of this cis-regulatory sequence affected only the domains identified in the transgenic analysis: the limb and face mesenchyme. The central importance of the DCE for endogenous Tcfap2a transcription in limb mesenchyme was reflected in the severe reduction of this expression domain in the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse. Expression was almost completely abolished in the anterior and medial regions of the limb mesenchyme and greatly reduced in the posterior. We speculate that it is the necessity to maintain limb mesenchyme expression that has led both to the conservation of this sequence from humans to zebrafish and the associated ability of the fifth introns from various species to drive transgene expression in the limb.

The loss of limb mesenchyme expression in the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse resulted in consistent alterations in anterior-posterior patterning of the forelimb, specifically postaxial polydactyly. The effect on limb patterning was confined to the forelimb, even though Tcfap2a expression was lost to an equivalent extent in the hind limb. This differential effect on forelimb development has also been observed in other mutant Tcfap2a mouse models (26, 31, 43). The postaxial polydactyly seen in the Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse can be produced by specific regimens of teratogen treatment, such as retinoic acid application, as well as by certain genetic changes, including those affecting shh signaling (17, 29, 33, 34). Links between the loss of Tcfap2a expression in the limb mesenchyme and these other developmental regulatory molecules remain to be determined, but two potential mechanisms can be envisioned based on these previous studies. One possibility is that loss of Tcfap2a expression would increase the size of the hand plate and so allow for an increase in the number of digits this structure could form. Alternatively, the hand plate could remain approximately the same size but the number of digit condensations in this field would be increased by perturbations in patterning. Thus, the primary importance of the DCE in the mouse would be to maintain Tcfap2a expression in the limb mesenchyme and so control the size of the hand plate and/or the size of the individual digit condensations. Moreover, species-specific differences in the sequence of the DCE might alter the size of the available limb field for patterning and so influence the evolution of limb or fin morphology.

The loss of the DCE had a more minor impact on endogenous Tcfap2a expression in the face, causing a moderate reduction in specific mRNA levels in the mesenchyme. Similarly, expression in the trunk neural crest, which is also a site of transgene expression imparted by the intact mouse enhancer, did not appear greatly affected in Tcfap2aDCE−/− mice. These findings indicate there that must be one or more additional cis-acting elements driving endogenous Tcfap2a expression in these tissues that remain to be identified. Such more distal enhancer sequences may be the critical regulatory elements for facial mesenchyme and trunk neural crest expression. Alternatively, the DCE and these other cis-acting elements may function redundantly, so that loss of the DCE alone is insufficient to abolish facial expression or alter development of the FNP.

In the context of craniofacial development, loss of the DCE and the associated reduction in Tcfap2a expression do not have a major impact on gross facial morphology during embryogenesis, in marked contrast to the major craniofacial defects observed in the Tcfap2a-null mice (31, 43). The Tcfap2aDCE−/− mouse phenotype, together with the data obtained from two different Cre recombinase transgenic lines that ablate Tcfap2a expression in the facial mesenchyme (4, 25), indicates that this tissue is unlikely to be the major site of AP-2α action in directing craniofacial development during embryogenesis. Further experiments will be required to pinpoint the appropriate site of Tcfap2a function in the face. Compared with the unique role of the DCE in directing Tcfap2a limb expression, the potential redundancy of this element for facial mesenchyme expression may help explain why the sequences responsible for the latter aspect of the pattern are not as well conserved through evolution. In this respect, alterations in the DCE may be one component of a multifactorial regulatory hierarchy that is responsible for regulating facial shape between species or between individuals within a species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Trang La, Danielle Nelson, Amy Donner, Carole Arthur, and Timothy Nottoli for technical help and advice. We thank members of the Williams laboratory for discussions and assistance, Kristin Artinger for critical reading of the manuscript, and Lee Niswander for Hoxd plasmids.

This research was supported by NIDCR grant RO1 DE12728 (T.W.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 November 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahituv, N., A. Erven, H. Fuchs, K. Guy, R. Ashery-Padan, T. Williams, M. H. de Angelis, K. B. Avraham, and K. P. Steel. 2004. An ENU-induced mutation in AP-2α leads to middle ear and ocular defects in Doarad mice. Mamm. Genome 15424-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boffelli, D., M. A. Nobrega, and E. M. Rubin. 2004. Comparative genomics at the vertebrate extremes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5456-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradshaw, M. S., C. S. Shashikant, H. G. Belting, J. A. Bollekens, and F. H. Ruddle. 1996. A long-range regulatory element of Hoxc8 identified by using the pClasper vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 932426-2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewer, S., W. Feng, J. Huang, S. Sullivan, and T. Williams. 2004. Wnt1-Cre mediated deletion of AP-2α causes multiple neural crest related defects. Dev. Biol. 267135-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewer, S., X. Jiang, S. Donaldson, T. Williams, and H. M. Sucov. 2002. Requirement for AP-2α in cardiac outflow tract morphogenesis. Mech. Dev. 110139-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cartharius, K., K. Frech, K. Grote, B. Klocke, M. Haltmeier, A. Klingenhoff, M. Frisch, M. Bayerlein, and T. Werner. 2005. MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics 212933-2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chazaud, C., M. Oulad-Abdelghani, P. Bouillet, D. Decimo, P. Chambon, and P. Dolle. 1996. AP-2.2, a novel gene related to AP-2, is expressed in the forebrain, limbs and face during mouse embryogenesis. Mech. Dev. 5483-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creaser, P. C., D. A. D'Argenio, and T. Williams. 1996. Comparative and functional analysis of the AP2 promoter indicates that conserved octamer and initiator elements are critical for activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 242597-2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies, A. F., K. Imaizumi, G. Mirza, R. S. Stephens, Y. Kuroki, M. Matsuno, and J. Ragoussis. 1998. Further evidence for the involvement of human chromosome 6p24 in the aetiology of orofacial clefting. J. Med. Genet. 35857-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies, A. F., G. Mirza, F. Flinter, and J. Ragoussis. 1999. An interstitial deletion of 6p24-p25 proximal to the FKHL7 locus and including AP-2α that affects anterior eye chamber development. J. Med. Genet. 36708-710. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies, A. F., G. Mirza, G. Sekhon, P. Turnpenny, F. Leroy, F. Speleman, C. Law, N. van Regemorter, E. Vamos, F. Flinter, and J. Ragoussis. 1999. Delineation of two distinct 6p deletion syndromes. Hum. Genet. 10464-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donner, A. L., and T. Williams. 2006. Frontal nasal prominence expression driven by Tcfap2a relies on a conserved binding site for STAT proteins. Dev. Dyn. 2351358-1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckert, D., S. Buhl, S. Weber, R. Jager, and H. Schorle. 2005. The AP-2 family of transcription factors. Genome Biol. 6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holzschuh, J., A. Barrallo-Gimeno, A. K. Ettl, K. Durr, E. W. Knapik, and W. Driever. 2003. Noradrenergic neurons in the zebrafish hindbrain are induced by retinoic acid and require tfap2a for expression of the neurotransmitter phenotype. Development 1305741-5754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerber, B., I. Monge, M. Mueller, P. J. Mitchell, and S. M. Cohen. 2001. The AP-2 transcription factor is required for joint formation and cell survival in Drosophila leg development. Development 1281231-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight, R. D., S. Nair, S. S. Nelson, A. Afshar, Y. Javidan, R. Geisler, G.-J. Rauch, and T. F. Schilling. 2003. lockjaw encodes a zebrafish tfap2a required for early neural crest development. Development 1305755-5768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, G. S., D. M. Kochhar, and M. D. Collins. 2004. Retinoid-induced limb malformations. Curr. Pharm. Des. 102657-2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin, J. F., A. Bradley, and E. N. Olson. 1995. The paired-like homeobox gene MHox is required for early events of skeletogenesis in multiple lineages. Genes Dev. 91237-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meulemans, D., and M. Bronner-Fraser. 2002. Amphioxus and lamprey AP-2 genes: implications for neural crest evolution and migration patterns. Development 1294953-4962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell, P. J., P. M. Timmons, J. M. Hebert, P. W. J. Rigby, and R. Tjian. 1991. Transcription factor AP-2 is expressed in neural crest cell lineages during mouse embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 5105-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohibullah, N., A. Donner, J. A. Ippolito, and T. Williams. 1999. SELEX and missing phosphate contact analyses reveal flexibility within the AP-2α protein: DNA binding complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 272760-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monge, I., R. Krishnamurthy, D. Sims, F. Hirth, M. Spengler, L. Kammermeier, H. Reichert, and P. J. Mitchell. 2001. Drosophila transcription factor AP-2 in proboscis, leg and brain central complex development. Development 1281239-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moser, M., J. Ruschoff, and R. Buettner. 1997. Comparative analysis of AP-2 alpha and AP-2 beta gene expression during murine embryogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 208115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy, A., M. Gertsenstein, K. Vintersten, and R. Behringer. 2003. Manipulating the mouse embryo, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 25.Nelson, D. K., and T. Williams. 2004. Frontonasal process-specific disruption of AP-2α results in postnatal midfacial hypoplasia, vascular anomalies, and nasal cavity defects. Dev. Biol. 26772-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nottoli, T., S. Hagopian-Donaldson, J. Zhang, A. Perkins, and T. Williams. 1998. AP-2-null cells disrupt morphogenesis of the eye, face, and limbs in chimeric mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9513714-13719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plessy, C., T. Dickmeis, F. Chalmel, and U. Strahle. 2005. Enhancer sequence conservation between vertebrates is favoured in developmental regulator genes. Trends Genet. 21207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prud'homme, B., N. Gompel, A. Rokas, V. A. Kassner, T. M. Williams, S. D. Yeh, J. R. True, and S. B. Carroll. 2006. Repeated morphological evolution through cis-regulatory changes in a pleiotropic gene. Nature 4401050-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robert, B., and Y. Lallemand. 2006. Anteroposterior patterning in the limb and digit specification: Contribution of mouse genetics. Dev. Dyn. 2352337-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanges, R., E. Kalmar, P. Claudiani, M. D'Amato, F. Muller, and E. Stupka. 2006. Shuffling of cis-regulatory elements is a pervasive feature of the vertebrate lineage. Genome Biol. 7R56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schorle, H., P. Meier, M. Buchert, R. Jaenisch, and P. J. Mitchell. 1996. Transcription factor AP-2 essential for cranial closure and craniofacial development. Nature 381235-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen, H., T. Wilkie, A. M. Ashique, M. Narvey, T. Zerucha, E. Savino, T. Williams, and J. M. Richman. 1997. Chicken transcription factor AP-2: cloning, expression and its role in outgrowth of facial promineneces and limb buds. Dev. Biol. 188248-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talamillo, A., M. F. Bastida, M. Fernandez-Teran, and M. A. Ros. 2005. The developing limb and the control of the number of digits. Clin. Genet. 67143-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tickle, C. 2006. Making digit patterns in the vertebrate limb. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 745-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Topping, A., P. Harris, and A. L. Moss. 2002. The 6p deletion syndrome: a new orofacial clefting syndrome and its implications for antenatal screening. Br. J. Plastic Surg. 5568-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ureta-Vidal, A., L. Ettwiller, and E. Birney. 2003. Comparative genomics: genome-wide analysis in metazoan eukaryotes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4251-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlieghe, D., A. Sandelin, P. J. De Bleser, K. Vleminckx, W. W. Wasserman, F. van Roy, and B. Lenhard. 2006. A new generation of JASPAR, the open-access repository for transcription factor binding site profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 34D95-D97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasserman, W. W., and A. Sandelin. 2004. Applied bioinformatics for the identification of regulatory elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5276-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West-Mays, J. A., J. Zhang, T. Nottoli, S. Hagopian-Donaldson, D. Libby, K. J. Strissel, and T. Williams. 1999. AP-2α transcription factor is required for early morphogenesis of the lens vesicle. Dev. Biol. 20646-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson, D. G. 1992. In situ hybridization: a practical approach. IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 41.Woolfe, A., M. Goodson, D. K. Goode, P. Snell, G. K. McEwen, T. Vavouri, S. F. Smith, P. North, H. Callaway, K. Kelly, K. Walter, I. Abnizova, W. Gilks, Y. J. Edwards, J. E. Cooke, and G. Elgar. 2005. Highly conserved non-coding sequences are associated with vertebrate development. PLoS Biol. 3e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, J., S. Brewer, J. Huang, and T. Williams. 2003. Overexpression of transcription factor AP-2α suppresses mammary gland growth and morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 256127-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, J., S. Hagopian-Donaldson, G. Serbedzija, J. Elsemore, D. Plehn-Dujowich, A. P. McMahon, R. A. Flavell, and T. Williams. 1996. Neural tube, skeletal and body wall defects in mice lacking transcription factor AP-2. Nature 381238-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, J., and T. Williams. 2003. Identification and regulation of tissue-specific cis-acting elements associated with the human AP-2α gene Dev. Dyn. 228194-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.