Abstract

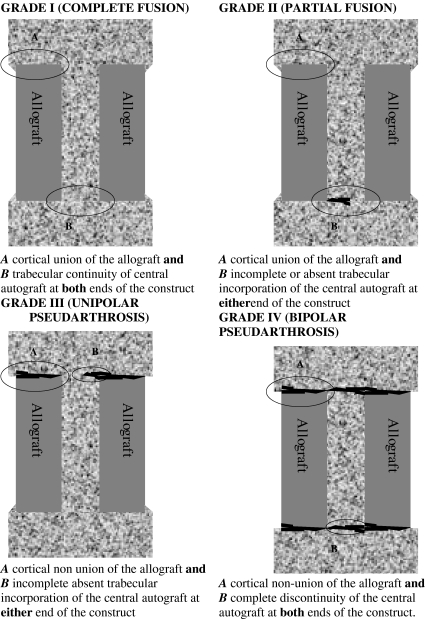

Anterior column reconstruction of the thoracolumbar spine by structural allograft has an increased potential for biological fusion when compared to synthetic reconstructive options. Estimation of cortical union and trabecular in-growth is, however, traditionally based on plain radiography, a technique lacking in sensitivity. A new assessment method of bony union using high-speed spiral CT imaging is proposed which reflects the gradually increasing biological stability of the construct. Grade I (complete fusion) implies cortical union of the allograft and central trabecular continuity. Grade II (partial fusion) implies cortical union of the structural allograft with partial trabecular incorporation. Grade III (unipolar pseudarthrosis) denotes superior or inferior cortical non-union of the central allograft with partial trabecular discontinuity centrally and Grade IV (bipolar pseudarthrosis) suggests both superior and inferior cortical non-union with a complete lack of central trabecular continuity. Twenty-five patients underwent anterior spinal reconstruction for a single level burst fracture between T4 and L5. At a minimum of two years follow up the subjects underwent high-speed spiral CT scanning through the reconstructed region of the thoracolumbar spine. The classification showed satisfactory interobserver (kappa score = 0.91) and intraobserver (kappa score = 0.95) reliability. The use of high-speed CT imaging in the assessment of structural allograft union may allow a more accurate assessment of union. The classification system presented allows a reproducible categorization of allograft incorporation with implications for treatment.

Keywords: Thoracolumbar reconstruction, Femoral allograft, CT, Interobserver

Introduction

Bone allograft reconstruction in anterior spinal surgery is now in its sixth decade [5, 6], though for a large portion of this time usage has been somewhat limited by risk of disease transmission, infection and graft versus host reaction. Recent advances in bone procurement, sterilization, preparation and storage have stimulated renewed interest in allograft as an alternative in load bearing vertebral reconstruction. Structural bone allograft has the advantage of potential for biologic fusion where graft union with the host bed is possible. This contrasts with metallic reconstructive devices, which act largely as a spacer with more limited capacity for bony union with the host vertebral endplates. The biologic capacity of allograft takes on its greatest significance in multiple segment anterior spinal reconstruction. Despite the potential of allograft to provide biologic stability in reconstruction, obstacles to predictable fusion remain. Of these, one of the most widely recognised is the low grade immune-based inflammatory reaction known to occur in response to bone allograft which may inhibit union and lead ultimately to fusion failure or graft fracture [8]. A number of radiological methods have been described to assess bony fusion in relation to structural bone allograft implantation in the spine [4, 17, 23]. These include motion measurement on lateral flexion and extension radiographs, progressive measurement of lost lordotic angle correction, graft collapse and resorption and percentage radiolucency surrounding the graft. The most direct method is by assessment of trabecular continuity between the graft and the adjacent native vertebra [2, 15, 17, 23]. This method relies on assessment by perpendicular radiographic images of the spine and may be subject to overestimation of fusion status in keeping with variation in radiographic quality and reproducibility, overlying visceral artefact and the three-dimensional nature of the subject fusion. High-speed spiral CT imaging provides greater detail in the assessment of anterior spinal reconstruction allowing three-dimensional analysis of the fusion mass. Fine cuts and accurate image reconstruction demonstrate the morphology of almost the entire tissue mass, reducing the possibility of overlooking a defect in bone union or incorporation. To the best of our knowledge, no classification of spinal allograft fusion using high-speed spiral CT scanning has yet been proposed. A validated radiological assessment technique is proposed for use in clinical and investigational settings.

Materials and methods

Surgical technique

Twenty-five consecutive patients underwent anterior corporectomy and reconstruction for high-grade thoracolumbar burst fracture using femoral diaphysis allograft and anterior screw plate instrumentation. Supplemental posterior instrumentation was also employed for fractures with a rotational element (AO type C injuries) [16]. All patients underwent retroperitoneal and anterior transthoracic approach for the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. Radical discectomy and corporectomy was performed and the adjacent vertebral endplates were decorticated to bleeding bone. A length of fresh frozen femoral diaphyseal allograft, sterilized by gamma irradiation (QLD Bone Bank, Australia) was then cut to appropriate length using a microsagittal oscillating saw. Autogenous cancellous bone of the fractured vertebral body was then morcellised and impacted into the medullary canal of the femoral allograft. The autograft/allograft composite was then inserted into the defect under compression and held with an anterior plating system. Patients were mobilized within 24 h and not braced. Patients with insufficiency fractures due to osteoporosis, infection or tumours were excluded from this study.

Radiological examination

Following hospital ethics committee approval, patients were contacted a minimum of 2 years postoperatively. All patients gave informed consent and underwent high-speed spiral CT examination using a Toshiba Aquilion MultiSlice spiral CT scanner. Acquisitions of 1 mm were performed and the images reformatted by sagittal and coronal reconstruction.

Validation

The patients were graded by the senior surgeon into one of four grades of fusion according to CT appearance schematically shown in Fig. 1. Grade I (complete fusion) implies cortical union of the allograft at bone cranial and caudal ends and continuity of trabecular pattern between the autograft within the medullary canal of the allograft and the adjacent cranial and caudal vertebral bodies. Grade II (partial fusion) implies cortical union of the allograft to the endplates at each end however with partial or absent trabecular continuity between the medullary autograft and the adjacent vertebral body bone at one or either end. Grade III (unipolar pseudarthrosis) denotes cranial or caudal cortical non-union of the allograft with associated central trabecular discontinuity and Grade IV (bipolar pseudarthrosis) suggests both superior and inferior cortical non union with a complete lack of central trabecular continuity. Images of 10 cases of the original 25 that were representative of each of the 4 grades of fusion were selected by a senior musculoskeletal radiologist (DL) and reliability of the classification was assessed by 2 senior spinal surgeons (RW, GA). All were blinded to the other’s responses and clinical outcome. Intraobserver reliability was assessed by representing the cases to the same examiners, although in different order, 6 weeks later. Inter and intraobserver reliability was estimated by calculating the kappa coefficient and the strength of agreement between the examiners was based on the Landis and Koch’s classification [14].

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of classification system

Results

Twenty-five patients who underwent anterior thoracolumbar corporectomy with femoral structural allograft reconstruction for high grade burst fracture were assessed by high-speed spiral CT examination at a minimum of 2 years postoperatively. The details of the study group are given in Table 1. There were 20 male and 5 female patients of mean age 31.6 years (range 15.9–58.1 years) reflecting the common distribution of major trauma. All patients were treated for thoracolumbar burst fractures in the distribution shown in Table 2. All anterior reconstructions were supplemented by anterior plating (Profile Plate, Depuy-AcroMed, Raynham, MA). Six patients also underwent supplemental posterior fixation (Universal Spine System, Synthes Paoli, PA) for rotatory fracture instability. Table 3 demonstrates allograft fusion grade assessment using the classification system described above. Representative CT images for each classification grade are shown in Fig. 2. The mean kappa coefficient value for interobserver reliability was calculated to be 0.91 and of intraobserver reliability after 6 weeks as 0.95. This represents near perfect agreement between observers and time points by Landis and Koch’s measurement [14].

Table 1.

Patient details

| ID | Gender | Age at surgery | Diagnosis | Autograft type | Anterior fixation | Posterior fixation | Fusion grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 16 | T4 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | None | 2 |

| 2 | M | 43 | L1 burst fracture | Local bone graft | Profile plate | None | 2 |

| 3 | M | 32 | L1 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 4 | M | 18 | L1 burst fracture | Local bone graft | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 5 | M | 34 | L1 burst fracture | Iliac Crest | Profile plate | USS | 1 |

| 6 | M | 33 | L1 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | USS | 2 |

| 7 | M | 33 | L1 burst fracture | Local bone graft | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 8 | M | 18 | L1 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | None | 2 |

| 9 | F | 58 | T12 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 10 | M | 51 | T12 burst fracture | Local bone graft | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 11 | M | 20 | L5 burst fracture | Iliac crest | Profile plate | USS | 1 |

| 12 | M | 42 | L1 chance fracture | Local bone graft | Profile plate | USS | 1 |

| 13 | M | 33 | T12 burst fracture | Iliac crest | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 14 | M | 44 | L1 burst fracture | Iliac crest | Profile plate | None | 2 |

| 15 | M | 17 | T12 burst fracture | Iliac crest | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 16 | M | 34 | T9 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 17 | F | 19 | T6 fracture/dislocation | Rib | Profile plate | None | 2 |

| 18 | M | 33 | L1 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | None | 2 |

| 19 | F | 34 | L1 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 20 | M | 33 | T11Burst fracture | Rib | Profile Plate | None | 2 |

| 21 | F | 27 | L1 burst fracture | Rib | Profile plate | None | 1 |

| 22 | M | 21 | L5 fracture/dislocation | Iliac crest | Profile plate | USS | 2 |

| 23 | M | 46 | L2 burst fracture | Iliac crest | Profile plate | None | 3 |

| 24 | M | 31 | L2 burst fracture | Iliac crest | Profile plate | None | 4 |

| 25 | M | 21 | L2 burst fracture | Local bone graft | Profile plate | USS | 4 |

Table 2.

Level of reconstruction

| Level | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| T4 | 1 (4%) |

| T6 | 1 (4%) |

| T9 | 1 (4%) |

| T11 | 1 (4%) |

| T12 | 4 (16%) |

| L1 | 12 (48%) |

| L2 | 3 (12%) |

| L5 | 2 (8%) |

Table 3.

Fusion grades of the original cohort

| Grade | No (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 13 (52%) |

| 2 | 9 (36%) |

| 3 | 1 (4%) |

| 4 | 2 (8%) |

Fig. 2.

Representative CT slices a Grade I, b Grade II, c Grade III, d Grade IV

Discussion

Albee [1] and Hibbs [10] independently reported fusion for spinal stabilization in the early 1900s. Since then, surgeons have come to rely on achieving solid fusion. In particular, the paraspinal muscle-preserving anterior approach has become a fundamental technique of reconstructive spinal surgery. In the modern era many techniques are available to facilitate and enhance spinal bone growth but few definitive criteria exist to ascertain successful fusion. Perhaps the most direct method of examination is by surgical exploration. However, as this lacks clinical justification, current practice has become heavily reliant on radiological techniques of assessment. For the most part, imaging techniques assume fusion integrity based on radiographic signs, providing evidence of radiographic fusion rather than actual fusion. One such method of assessing radiographic fusion is by dynamic lateral spinal radiographs where an interbody mass is considered fused if there is less than 5° of measurable motion between flexion and extension [19]. In 2001 a survey of eight senior spinal surgeons resulted in five of eight investigators being satisfied that lateral dynamic spinal radiographs had an acceptably high positive predictive value for interbody fusion whilst the remainder disputed the accuracy of the method [18]. Fraser pointed out in a pilot study of the AcroFlex artificial disc that flexion–extension radiographs detected no measurable motion on weight bearing 6 months following the procedure, however that subsequent fluoroscopy showed a mean of 10° of movement in the sagittal plane at the target level [18]. He attributed the discrepancy to the instructions given at radiographic examination and the operation of the fluoroscope. Boden noted that while the presence of residual segmental motion generally suggests that a non-union is present, lack of motion on any type of stress radiographs does not necessarily imply spinal fusion [18]. Other commonly employed radiological signs of fusion are loss of angle of correction, graft collapse and radiolucency at either end of the allograft. Again, the presence of any of these implies non-union but their absence does not guarantee that fusion has occurred. By contrast, the ability to image the presence or absence of bony trabecular continuity on either side of the interbody implant allows direct examination of fusion status. This must then be considered a more desirable technique of union assessment. Moreover, several authors have suggested that the ability of plain radiographic examination to demonstrate trabecular structure is limited [12, 13, 21, 24]. This is probably due to the inability of plain radiographs to assess intricate three-dimensional structure and to detect subtle differences in tissue density.

Tuli et al. [24] studied the reliability of plain static radiographs in predicting the presence or absence of fusion. In their study of 57 patients, the level of agreement between 2 independent neuroradiologists who were blinded to each other’s assessment and subsequent clinical outcome was 0.61 at 6 weeks and 0.44 at 12 weeks. They concluded that plain radiographs were quite unreliable in predicting fusion based on presence or absence of trabeculation.

Santos et al. [20] studied anterior spinal fusion in a group of 32 patients who had undergone surgery by interbody carbon fibre cages with 5 year follow-up. Static radiographic analysis yielded a fusion rate of 86 and 84% using the method described by Hutter [11]. Assessment by dynamic radiography with 2° cut-off lowered the successful fusion rate to 74%, and raised it to 96% when the 5° cut-off accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was employed. High-speed helical CT imaging resulted in a fusion rate of 65% [20]. The authors concluded that both static and dynamic radiographs tend to overestimate the true rate of union in cases of anterior interbody fusion by carbon fibre cage. In many cases the fusion defect was within the cavity of the cage (“locked pseudarthrosis”), beyond detection by plain radiographs. Sarwat et al. [21] noted that dynamic views are of limited value in providing information on spinal stability at least in the period up to 6 months following surgery due to patients’ experience of postoperative muscular pain at the terminal limits of spinal flexion and extension. Kumar et al. [13] retrospectively reviewed 32 patients who underwent single level anterior fusion with femoral ring allografts with a mean follow-up of 36 months. Radiographic union was identified in 66% of patients on static films, however if flexion/extension radiographs were taken into account (functional arthrodesis), an additional 22% of patients were considered to have had a successful fusion. Similarly Kozak et al. [12] reviewed 45 patients with anterior lumbar interbody fusion by femoral ring allograft and cancellous interference bone screws. They found solid fusion in 84% of fusion levels with an additional 13% having bridging bone either anteriorly or posteriorly with associated stability as determined by radiographs taken in flexion and extension. The latter addition of dynamic radiographic assessment raises the possibility that the corresponding increase in the number of cases of fusion identified may in fact simply have been an elimination of obvious non-union rather than a conclusive demonstration of successful fusion. Furthermore, Tuli et al. [24] have noted that angular measurement in the analysis of flexion/extension views is complicated by the reliability of a goniometer and its use making the technique prone to inaccuracy.

High-speed spiral CT allows volume scanning and overcomes the limitations of plain radiography by removing the limitations of superimposition of structures, enabling the demonstration of subtle differences in tissue density. CT imaging also correlates well with histology and micro-radiography, implying that high quality computerized tomography can be as accurate as open surgical exploration in the assessment of fusion status [9]. Cunningham et al. [7] in their study of rhBMP-1 using BAK cages in sheep, found a 100% correlation between CT imaging and histological microradiographs in the BAK-autograft group. They were able to demonstrate in all specimens classified as fused at 4 months definitive evidence of contiguous well-organized bony trabeculation through the BAK cages spanning the fusion site from the adjacent vertebral bodies. Spinal fusion has been described as a time to event phenomenon whereby the observation of fusion indicators is made at different times in each individual case [25]. As such, the absence of observed indicators of fusion such as graft remodelling is not necessarily an indication of non-union. Any proposed classification system must therefore describe both findings of fusion and pseudoarthrosis in each grade to accurately represent the state of healing at any point following surgery.

Bridwell et al. [3] described a grading system for success in anterior interbody fusion using femoral allograft ring. The system is based on plain radiographic findings and state of fusion is divided into one of four grades. Grade I is defined as fusion with remodelling and trabeculae present; Grade II is an intact graft with incomplete remodelling and no lucency present; Grade III is an intact graft with potential lucency at the cranial or caudal end; Grade IV is absent fusion with collapse/resorption of the graft. A potential difficulty in the interpretation of this system may be that the distinction between grades III and IV may be more a reflection of the chronicity of established graft non-union rather than grade III implying a delayed process of healing with ongoing potential for fusion. That is to say that the mere absence of graft collapse in Grade III does not necessarily denote a “lesser state of non-union” than in Grade IV. Also, the term “potential lucency” is somewhat difficult to apply to plain radiographs in practical terms and the intermediate grades of the system account only for evidence of pseudoarthrosis and not the state of graft union to the adjacent endplates. Moreover it seems likely that sensitivity for pseudoarthrosis is enhanced by CT scanning and subsequent assessment systems will no doubt take this into consideration. The classification proposed here is based on four grades of increasing biological stability of the construct.

The grading system has inter- and intraobserver reliability of 0.91 and 0.95, respectively. This is in accord with the report of Shah et al. [22] who compared plain radiography with CT imaging for evaluation of lumbar interbody fusion using titanium cages and transpedicular instrumentation and found near perfect agreement (kappa value 0.85) between two observers of the CT examinations. The latter is in contrast to the observer reliability of graft assessment using plain radiography as determined by Tuli et al. [24]. As yet there are no reports stipulating the minimum number of CT images in any plane that are required to definitively establish the presence of fusion. Using high quality, high-speed spiral CT imaging, we are of the belief that one image in both sagittal and coronal planes which conclusively demonstrates graft union and trabecular continuity is sufficient. Not withstanding, the extent of fusion in size and strength may well vary according to the evidence of union observed in contiguous CT slices, although estimates of fusion mass strength based on area shown on CT were not the subject of this work. In this study the CT image with the highest grade was taken as indicative of the state of union in that plane in each individual case. In symptomatic patients, grades III and IV were taken as evidence of non-union and further treatment instituted as necessary. Grades I and II were considered evidence of fusion or impending fusion.

Conclusion

Bone allograft is a biologic alternative for anterior column reconstruction of the spine, whereby both cortical allograft to endplate union and central cancellous autograft to endplate incorporation may occur. A new grading system of allograft/autograft composite union in the spine using high-speed spiral CT imaging is proposed. The classification system described in this paper allows for the reliable radiological determination of the biological incorporation and stability of allograft constructs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Synthes Asia Pacific, AOSpine Asia Pacific and the QLD Government, Department of State Development. The authors thank Drs Geoff Askin and David Lisle for their involvement in the interobserver study

References

- 1.Albee F. Transplantation of a portion of the tibia into the spine for Pott’s disease: a preliminary report. JAMA. 1911;57:885–886. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop RC, Moore KA, Hadley MN. Anterior cervical interbody fusion using allogeneic and allogeneic bone graft substrate: a prospective comparative analysis. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:206–210. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.2.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, McEneryKW, Baldus C, Blanke K. Anterior structural allografts in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Spine. 1995;20:1410–1418. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199506000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butterman GR, Glazer PA, Hu SS, Bradford DS. Revision of failed lumbar fusion: a comparison of anterior autograft and allograft spine. Spine. 1997;22:2748–2755. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cloward RB. The treatment of ruptured lumbar intervertebral discs by vertebral fusion III method of use of banked bone. Ann Surg. 1952;136:987–992. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195212000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cloward RB. Vertebral body fusion for ruptured cervical discs: description of instruments and operative technic. Am J Surg. 1959;98:722–727. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(59)90498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham BW, Kanayama M, Parker L.M, Weis JC, Sefter JC, Fedder McAfee IL PC. Osteogenic protein versus autologous interbody arthrodesis in the sheep thoracic spine. Spine. 1999;24:509–518. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199903150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrler Vaccaro DM AR. The use of allograft bone in lumbar spine surgery. Clin Orthop. 2000;371:38–45. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200002000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelke K, Graeff W, Meiss L, Hahn Delling M G. High spatial resolution imaging of bone mineral using computed microtomography comparison with microradiography and undecalcified histologic sections. Invest Radiol. 1993;28:341–349. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199304000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hibbs R. An operation for Pott’s disease of the spine. JAMA. 1912;59:43. doi: 10.1097/00000658-191205000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutter G. Posterior intervertebral body fusion a 25 year study. Clin Orthop. 1983;179:86–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozak JA, Heilman O’Brien AE JP. Anterior lumber fusion option. Clin Orthop. 1994;300:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Kozak JA, Doherty Dickson BJ JH. Interspace distraction and grafts subsidence after anterior lumbar fusion with femoral strut allograft. Spine. 1993;18:2393–2400. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landis Koch JR GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1997;33:154–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewandrowski KU, Hecht AC, DeLaney TF, Chapman PA, Hornicek Pedlow FJ FX. Anterior spinal arthrodesis with structural cortical allograft and instrumentation for spinal tumor surgery. Spine. 2004;29:1150–1159. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein SD, Harms Nazarian J S. A comprehensie classification of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J. 1994;3:184–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02221591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin GJ, Jr, Haid RW, Jr, MacMillan M, Rodts Berkman GE R., Jr Anterior cervical discectomy with freeze–dried fibula allograft: overview of 317 cases and literature review. Spine. 1999;24:852–859. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199905010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAfee PC, Boden SD, Brantigan JW, Fraser RD, Kuslich SD, Oxland TR, Panjabi MM, Ray Zdeblick CD TA. Symposium. A critical discrepancy—a criteria of successful arthrodesis following interbody spinal fusions. Spine. 2001;26:320–334. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearcy M, Burrough S. Assessment of bony union after interbody fusion of teh lumbar spine using a biplanar radiographic technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64-B:228–322. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.64B2.7040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos ERG, Goss DG, Morcom Fraser RK RD. Radiologic assessment of interbody fusion using carbon fiber cages. Spine. 2003;28:997–1001. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200305150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarwat AM, O’Brien JP, Renton Sutcliffe P JC. The use of allograft (and avoidance of autograft) in anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a critical analysis. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:237–241. doi: 10.1007/s005860000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah RR, Mohammed S, Saifuddin Taylor A B. Comparison of plain radiographs with CT scan to evaluate interbody fusion following the use of titanium interbody cages and transpedicular instrumentation. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:378–385. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0517-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh K, DeWald CJ, Hammerberg KW, DeWald RL. Long structural allografts in the treatment of anterior spinl column defect. Clin Orthop. 2002;394:121–129. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuli SK, Chen P, Eichler ME, Woodard EJ. Reliability of radiologic assessment of fusion: cervical fibular allograft model. Spine. 2004;29:856–860. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200404150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuli SK, Tuli J, Chen P, Woodard EJ. Fusion rate: a time-to-event Phenomenon. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:47–51. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.1.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]