Abstract

Rickettsia rickettsii is an obligate intracellular pathogen that is the causative agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. To identify genes involved in the virulence of R. rickettsii, the genome of an avirulent strain, R. rickettsii Iowa, was sequenced and compared to the genome of the virulent strain R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. R. rickettsii Iowa is avirulent in a guinea pig model of infection and displays altered plaque morphology with decreased lysis of infected host cells. Comparison of the two genomes revealed that R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith share a high degree of sequence identity. A whole-genome alignment comparing R. rickettsii Iowa to R. rickettsii Sheila Smith revealed a total of 143 deletions for the two strains. A subsequent single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis comparing Iowa to Sheila Smith revealed 492 SNPs for the two genomes. One of the deletions in R. rickettsii Iowa truncates rompA, encoding a major surface antigen (rickettsial outer membrane protein A [rOmpA]) and member of the autotransporter family, 660 bp from the start of translation. Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence confirmed the absence of rOmpA from R. rickettsii Iowa. In addition, R. rickettsii Iowa is defective in the processing of rOmpB, an autotransporter and also a major surface antigen of spotted fever group rickettsiae. Disruption of rompA and the defect in rOmpB processing are most likely factors that contribute to the avirulence of R. rickettsii Iowa. Genomic differences between the two strains do not significantly alter gene expression as analysis of microarrays revealed only four differences in gene expression between R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R. Although R. rickettsii Iowa does not cause apparent disease, infection of guinea pigs with this strain confers protection against subsequent challenge with the virulent strain R. rickettsii Sheila Smith.

Rickettsia rickettsii is a member of the spotted fever group of rickettsiae and the etiologic agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF). R. rickettsii is a small obligate intracellular gram-negative organism that is maintained in its tick host through transovarial transmission (17, 31). Infection with R. rickettsii occurs through the bite of an infected tick. Once the organism gains access to the host, it is able to replicate within the host vascular endothelial cells and spread from cell to cell by polymerizing host cell actin (20). Damage to vascular endothelial cells by R. rickettsii leads to increased vascular permeability and leakage of fluid into the interstices, causing the characteristic rash observed in RMSF (19). Infection with R. rickettsii results in a severe and potentially life-threatening disease if it is not diagnosed and treated properly. While much is known about the progression of the disease, the molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of RMSF are poorly understood.

Rickettsiae are separated into two groups: the spotted fever group and the typhus group. The genomes of several rickettsiae have recently been completed and have provided an abundance of genomic information; these genomes include those of R. bellii RML369-C (27), R. conorii Malish 7 (26), R. felis URRWXCal2 (28), R. prowazekii Madrid E (6), R. rickettsii Sheila Smith (GenBank accession no. AADJ01000001), R. sibirica (GenBank accession no. AABW01000001), and R. typhi Wilmington (25). The availability of genomic sequences allows comparisons between the two groups (25) and between virulent and avirulent strains of rickettsiae (13).

R. rickettsii Iowa was obtained from guinea pigs inoculated with a Dermacentor variabilis suspension (8). Interestingly, R. rickettsii Iowa displayed various degrees of virulence in the guinea pig infection model during passage in eggs (8). Early passages showed mild virulence, but subsequently this strain became highly virulent before eventually displaying an avirulent phenotype. Analysis of a high-egg-passage clone demonstrated that the strain was deficient in the ability to lyse Vero cells, forming indistinct plaques compared to the clear plaques observed for R. rickettsii strain R (18). Is was also found that R. rickettsii Iowa was defective in processing rickettsial outer membrane protein B (rOmpB) from its 168-kDa precursor into its 120- and 32-kDa forms (18). It has yet to be determined if the inability of R. rickettsii Iowa to lyse Vero cells and cause infection in guinea pigs is the result of defective rOmpB processing, some other mutation, or a combination of these two factors.

The lack of good genetic tools for rickettsiae has made the identification of virulence genes difficult. A number of studies have looked at genetic, antigenic, and phenotypic differences between unique R. rickettsii strains (1, 3, 4, 12). However, the complete genomes of virulent and avirulent strains of R. rickettsii have yet to be compared.

Recently, the genomic sequence of the virulent strain R. rickettsii Sheila Smith was completed (GenBank accession no. AADJ01000001). To identify genes potentially involved in the virulence of R. rickettsii, we determined the genomic sequence of the cloned avirulent strain R. rickettsii Iowa (GenBank accession no. CP000766) and compared it to the R. rickettsii Sheila Smith genomic sequence. Here we describe genomic and expression differences that may contribute to the avirulence of R. rickettsii Iowa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rickettsiae.

R. rickettsii strain R, R. rickettsii Sheila Smith, and R. rickettsii Iowa (8) were propagated in Vero cells using M199 medium and were purified by Renografin density gradient centrifugation (33).

Genomic DNA purification.

To isolate R. rickettsii Iowa genomic DNA, purified R. rickettsii Iowa was first lysed by incubation in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K for 2 h at 60°C. After 2 h, 1 volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol was added, and the mixture was centrifuged for 3 min at 20,000 × g. The aqueous phase was removed and subjected to another round of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction. DNA was precipitated with 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.0) plus 0.6 volume of isopropanol and resuspended in Tris-EDTA (pH 8.0).

Genome sequencing, annotation, and alignment.

The genome of R. rickettsii Iowa (GenBank accession no. CP000766) was sequenced by Integrated Genomics, Inc. using standard sequencing procedures (10, 21, 23). For regions of the genome with low sequence quality, directed sequencing was performed to increase the minimum consensus base quality to an average of Q40 (99.99% accuracy of base call) throughout. Manual efforts and proprietary software (Integrated Genomics) were used to identify open reading frame (ORFs) in the genome of R. rickettsii Iowa, and the ORFs were then entered into the ERGO bioinformatics suite (Integrated Genomics) for final annotation (29). GC skew was calculated by determining (C − G)/(G + C) with a 20-kb sliding window moving in 500-bp incremental steps. The G+C content was calculated using 2- and 20-kb sliding windows compared to the total G+C content of the entire chromosome.

The similarity threshold was set at 10e−10 for the conserved-versus-unique ORF comparison of R. rickettsii Sheila Smith and R. rickettsii Iowa. Annotation of the R. rickettsii Iowa genome produced 245 ORFs that were not called or were absent from R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. A focused ORF-to-ORF comparison and a corresponding DNA-to-DNA comparison were performed for the R. rickettsii Iowa annotation and the unfinished R. rickettsii Sheila Smith genome annotation. Based on this analysis, 223 of the 245 ORFs were found to be present in R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. These ORFs were removed from R. rickettsii Iowa during our comparison in order to obtain a more accurate assessment of unique genes versus conserved genes. However, the annotation files submitted to GenBank contain these 223 ORFs.

A whole-genome alignment was performed using MAUVE (9) software according to the manufacturer's instructions. All other DNA and protein alignments were performed using the ERGO bioinformatics suite.

SNP identification protocol.

To identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), all ORFs, RNAs, and intergenic regions from R. rickettsii Sheila Smith and R. rickettsii Iowa were clustered into these groups. The DNA types were further filtered using a similarity cutoff of 80% of the bases between the two genomes of the same type. If the overall lengths of features differed by less than 10%, the features were considered clustered and were used for calculation of SNPs. Features whose lengths differed by more than 10% were analyzed manually. All clusters of each feature type were aligned using ClustalW, and SNPs were assigned where the aligned sequences had a change in a nucleotide at a specific location in the alignment.

Multilocus sequence alignment.

DNA coding sequences of the glt, gyrB, ompB, recA, and sca4 genes were collected from the following genomes (genome accession numbers are indicated in parentheses): R. akari (NZ_AAFE00000000), R. felis (CP000053.1), R. conorii (AE006914.1), R. sibirica (NZ_AABW00000000), R. rickettsii (NZ_AADJ00000000), Rickettsia prowazekii (AJ235269.1), R. typhi (AE017197.1), R. canadensis (NZ_AAFF00000000), and R. bellii (NZ_AARC00000000). Gene sequences were concatenated 5′ to 3′ in the following order: glt, gyrB, ompB, recA, sca4. Individual genes and concatenated sequences at the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence levels were analyzed with MacVector software (version 6.0; Oxford Molecular). Individual and concatenated DNA sequences were first aligned with the Clustal V program in the Lasergene software package (Dnastar). The alignments were transferred into the MacClade (Sinauer Associates) program for manual correction. MacClade output files were opened in PAUP (Sinauer Associates), and maximum-likelihood neighbor-joining trees were generated. Trees were rooted by making the outgroup (R. bellii) paraphyletic with respect to the ingroup. The robustness of clade designations was tested with a full heuristic search and 10,000 bootstrap replicates.

Guinea pig infection.

Six-week-old female Hartley guinea pigs were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1,000 PFU of either R. rickettsii Sheila Smith or R. rickettsii Iowa or an equivalent amount of formaldehyde-fixed R. rickettsii strain R, and their temperatures were monitored rectally for 14 days after infection. For immunization experiments guinea pigs were challenged i.p. with 1,000 PFU of R. rickettsii Sheila Smith 30 days after the initial infection. Blood was drawn from the guinea pigs at zero time and 30 days after infection, and antibody titers were determined by microimmunofluorescence.

LDH release assay.

Monolayers of Vero cells in 96-well plates were infected with either R. rickettsii strain R or R. rickettsii Iowa at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. The percentage of total lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the medium by R. rickettsii was determined using a CytoTox-ONE homogeneous membrane integrity assay kit (Promega) on days 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 as described by the manufacturer.

Western blotting.

R. rickettsii strain R and R. rickettsii Iowa (2 × 108 cells) were resuspended in 100 μl of Laemmli buffer. Protein from equal volumes of solubilized cells was separated by electrophoresis on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel for 1 h at 150 V. Proteins were transferred at 100 V for 1 h to a nitrocellulose membrane, and rOmpA was detected using anti-rOmpA monoclonal antibodies 13-3 and 13-5 (2).

Dual fluorescence staining of rickettsiae and F-actin.

R. rickettsii strain R suspended in Hanks balanced salt solution was used to infect monolayers of Vero cells on 12-mm coverslips at an MOI of 5 for 30 min. Fresh M199 medium plus 2% fetal bovine serum was then added, and incubation was continued at 34°C. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, 25 mM NaPO4, 150 mM NaCl for 20 min, which was followed by three washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (25 mM NaPO4, 150 mM NaCl). Cells were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 4 min to permeabilize the plasma membrane. Cells were then washed three times with PBS. R. rickettsii strain R and R. rickettsii Iowa were first incubated with anti-OmpB monoclonal antibody 13-2 (2) and stained with anti-mouse immunoglobulin Alexa 488. After the rickettsiae were stained, F-actin was labeled with rhodamine phalloidin (10 U/ml). Cells were then washed three times with PBS and viewed with a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope.

Microarray analysis.

Monolayers of Vero cells in T25 tissue culture flasks were infected with R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R at an MOI of 0.05 and incubated for 3 days. To harvest RNA, the medium was removed and 1 ml of Trizol (Invitrogen) was added to each T25 flask for RNA extraction. Samples were transferred to 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, and 200 μl of chloroform was added. The samples were then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min. The aqueous phase (∼750 μl) was removed and dried to obtain a volume of ∼200 μl, and the RNA was purified using an RNeasy 96 kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified RNA was subjected to two rounds of DNAfree (Ambion) treatment and repurified using the RNeasy 96 kit. SuperScript III (Invitrogen) was used to make cDNA from 10 μg of purified RNA. Five micrograms of cDNA was digested with 0.005 U DNase I (Roche) and labeled using a BioArray terminal labeling kit with biotin-ddUTP (Enzo) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Biotinylated R. rickettsii cDNA was hybridized to a custom Affymetrix GeneChip (no. 3 RMLchip3a520351F) containing 1,991 probe sets from two different R. rickettsii strains (Sheila Smith and Iowa). Hybridization was performed at 40°C, while scanning and analyses were performed as previously described (32).

Microarray data accession number.

Microarray data are posted on the Gene Expression Omnibus website (www.ncbi.nlm.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE8041.

RESULTS

R. rickettsii Iowa is avirulent and defective in cell lysis.

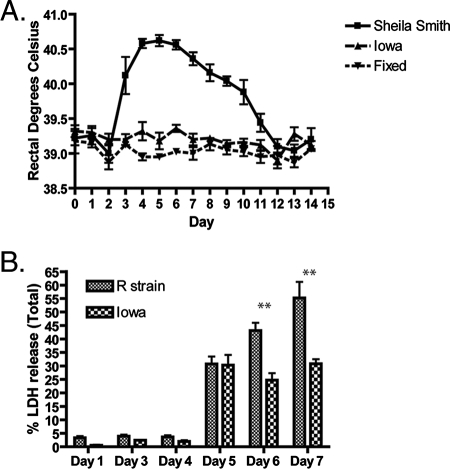

A clonal isolate of R. rickettsii Iowa was derived from a single plaque from a high-egg-passage stock (EP 271). To confirm that this isolate was avirulent, its ability to induce fever in female Hartley guinea pigs was compared to that of R. rickettsii Sheila Smith (Fig. 1A). R. rickettsii Iowa did not induce fever in female Hartley guinea pigs when 1,000 PFU was injected i.p. In contrast, R. rickettsii Sheila Smith induced marked fever starting on day 3 after infection, which continued until day 12. Guinea pigs infected with R. rickettsii Sheila Smith or R. rickettsii Iowa also developed high titers of antibodies (see below). Animals inoculated with an equivalent amount of formalin-killed rickettsiae did not develop fever or detectable titers of antibodies (see below), suggesting that replication of R. rickettsii Iowa was required to produce sufficient antigenic stimulus to induce significant antibody production. These data suggest that R. rickettsii Iowa infected but was unable to induce fever in female Hartley guinea pigs.

FIG. 1.

R. rickettsii Iowa virulence and the ability of R. rickettsii Iowa to lyse Vero cells are attenuated. (A) Female Hartley guinea pigs were infected with 1,000 PFU of R. rickettsii Sheila Smith or R. rickettsii Iowa or inoculated with paraformaldehyde-fixed rickettsiae (Fixed), and their temperatures were monitored for 14 days postinfection. (B) Monolayers of Vero cells grown in 96-well plates were infected with either R. rickettsii strain R or R. rickettsii Iowa, and the percentages of LDH released into the media were determined on days 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 postinfection. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) are indicated above the bars (two asterisks) and were determined by performing a two-way analysis of variance for the relative fluorescence units using GraphPad Prism software (n = 5).

R. rickettsii Iowa has previously been shown to form opaque plaques, compared to the clear plaques produced by R. rickettsii strain R (18). This observation suggests that R. rickettsii Iowa is deficient in host cell lysis. To quantify the abilities of R. rickettsii strain R and R. rickettsii Iowa to lyse cells, release of LDH into the media was measured during infection (11) (Fig. 1B). Consistent with the observed plaque morphologies, the results showed that there was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) in the amounts of LDH released on days 6 and 7 postinfection by R. rickettsii strain R and R. rickettsii Iowa. The data indicate that there is a correlation between the ability of R. rickettsii to lyse host cells and the virulence of the organism.

Both R. rickettsii strain R and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith were isolated in western Montana, and they have similar virulence traits (1, 3, 4, 11). We further showed that R. rickettsii strain R and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith have no major differences in gene content by hybridizing genomic DNA from the two strains to microarrays containing both the Sheila Smith and Iowa genomes (data not shown). We used both R. rickettsii strain R and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith as representative western Montana strains throughout this study based on their phenotypic and genetic similarities.

Genomic characterization.

To determine which genes may be involved in the virulence of R. rickettsii, the genomic sequence of R. rickettsii Iowa was determined and compared to that of R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. The genome of R. rickettsii Iowa consists of a single circular chromosome predicted to contain 1,567 ORFs. A high degree of sequence identity (96.6%) was observed for the two genomes. When deleted regions are discounted, the identity between the two genomes is ∼ 99%. A multilocus sequence alignment confirmed that R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith are closely related (Fig. 2), and the results were similar to previously published results (14). Genomic features of both strains are listed in Table 1, and a detailed comparison of the two genomes is shown in Fig. 3. Despite the high degree of identity between the two genomes, a number of strain-specific insertions, deletions, and SNPs were identified.

FIG. 2.

Phylogram showing that R. rickettsii Sheila Smith and R. rickettsii Iowa are closely related. The following concatenated sequences of Rickettsia species were used for the analysis: glt, gyrB, ompB, recA, and sca4. R. bellii was used as an outgroup. The tree was constructed with Clustal V and the neighbor-joining method with 10,000 bootstrap replicates. A number at a node is the percentage of bootstrap replicates that supported the branching pattern to the right. The scale bar for the branch lengths indicates the number of substitutions per site.

TABLE 1.

Genomic statistics for R. rickettsii Sheila Smith and R. rickettsii Iowa

| Strain | Total no. of bases sequenced | Total no. of G+C bases | G+C content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smith | 1,257,710 | 408,346 | 32.47 |

| Iowa | 1,268,175 | 411,482 | 32.45 |

FIG. 3.

Circular diagram of the R. rickettsii Iowa genome. The outer circle is an alignment of each ORF identified in R. rickettsii Iowa compared to ORFs in R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. ORFs that share an E value cutoff of ≥1e10−10 are gray, while ORFs that lack R. rickettsii Iowa homology are black. The second and third circles are the predicted ORFs in R. rickettsii Iowa and the strand of DNA that encodes them (orange, positive strand; blue, negative strand). The fourth circle shows the locations of RNA-encoding regions; tRNAs are green, and rRNAs are red. The fifth circle shows all of the ORFs color coded by functional category, as indicated at the bottom. The sixth circle shows GC skew, and the seventh circle shows the G+C content with a sliding 20-kb window.

Deletion analysis.

To determine genomic differences between R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith, a whole-genome alignment was prepared and manually inspected for the presence of small deletions. A total of 143 deletions ranging from 1 bp to more than 10,000 bp were found for the two genomes. Forty-seven of these deletions were located within predicted ORFs; 23 of them were deletions in R. rickettsii Sheila Smith compared to strain Iowa (Table 2), and 24 were deletions in R. rickettsii Iowa compared to strain Sheila Smith (Table 3). These deletions included gene truncations, in-frame deletions, frameshifts, and total gene deletions.

TABLE 2.

Deletions in R. rickettsii Sheila Smith compared to R. rickettsii Iowa

| Location | Size (bp) | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Rick02001026/Rick02001027 | 10,585 | Deletes RrIowa0964-RrIowa0983 |

| Rick02000769/Rick02000770 | 857 | Deletes RrIowa0725-RrIowa0726 |

| Rick02001265 | 609 | Truncated by 93 bp |

| Rick02000149 | 72 | In-frame deletion |

| Rick02001088 | 27 | Truncated by 36 bp |

| Rick02000842 | 23 | Frameshift adds 85 bp |

| Rick02000149 | 16 | In-frame deletion |

| Rick02001130 | 16 | Frameshift adds 209 bp |

| Rick02001362 | 6 | In-frame deletion |

| Rick02001493 | 4 | Truncated by 40 bp |

| Rick02000149 | 3 | In-frame deletion |

| Rick02001442 | 3 | In-frame deletion |

| Rick02001549 | 3 | In-frame deletion |

| Rick02000797 | 2 | Frameshift adds 268 bp |

| Rick02000821 | 2 | Truncated by 97 bp |

| Rick02000195 | 1 | Frameshift adds 7 bp |

| Rick02000634 | 1 | Frameshift adds 236 bp |

| Rick02000747 | 1 | Frameshift adds 25 bp |

| Rick02000852 | 1 | Frameshift adds 18 bp |

| Rick02000960 | 1 | Frameshift adds 144 bp |

| Rick02001268 | 1 | Frameshift adds 91 bp |

| Rick02001323 | 1 | Frameshift adds 159 bp |

| Rick02001512 | 1 | Truncated by 312 bp |

TABLE 3.

Deletions in R. rickettsii Iowa compared to R. rickettsii Sheila Smith

| Location | Size (bp) | Result |

|---|---|---|

| RrIowa1459 | 891 | In-frame deletion |

| RrIowa1088 | 590 | Truncated by 582 bp |

| RrIowa1055 | 39 | In-frame deletion |

| RrIowa1479 | 32 | Truncated by 121 bp |

| RrIowa0663 | 14 | Frameshift adds 437 bp |

| RrIowa1265 | 13 | Truncated by 69 bp |

| RrIowa0440 | 11 | Frameshift adds 155 bp |

| RrIowa0830 | 11 | Frameshift adds 8 bp |

| RrIowa0380 | 5 | Frameshift adds 225 bp |

| RrIowa0280 | 4 | Frameshift adds 81 bp |

| RrIowa0664 | 4 | Truncated by 341 bp |

| RrIowa0756 | 4 | Truncated by 50 bp |

| RrIowa0664 | 3 | In-frame deletion |

| RrIowa0855 | 2 | Truncated by 133 bp |

| RrIowa0871 | 2 | Truncated by 42 bp |

| RrIowa0517 | 1 | Frameshift adds 51 bp |

| RrIowa0622 | 1 | Changes start codon to GTG from TTG |

| RrIowa0623 | 1 | Truncated by 116 bp |

| RrIowa0630 | 1 | Frameshift adds 130 bp |

| RrIowa0792 | 1 | Truncated by 457 bp |

| RrIowa0867 | 1 | Frameshift adds 481 bp |

| RrIowa0917 | 1 | Truncated by 38 bp |

| RrIowa1113 | 1 | Frameshift adds 199 bp |

| RrIowa1460 | 1 | Truncated by 4,536 bp |

Evidence for genomic reduction.

The largest difference between R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith is a ∼10-kb deletion from R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. Genes in this region in R. rickettsii Iowa appear to be undergoing degradation. An alignment of this region with the sequences of other rickettsial species suggested that some of the genes in this region have been fragmented or lost in some species and appear to be intact in other species (Fig. 4). Reductive evolution suggests that these genes may not be required for survival within the host or vector (5). One of the genes in this region encodes a potential integral membrane protein, and another encodes a protein with homology to enoyl-coenzyme A hydratase. Because enoyl-coenzyme A hydratase has been associated with pathways involved in processes such as fatty acid biosynthesis, fatty acid metabolism, amino acid degradation, and metabolism, it is reasonable to speculate that R. rickettsii may not require the function of this gene to survive within its host cell. Therefore, deletion of this ∼10-kb region in R. rickettsii Iowa may represent an intermediate step in the process of genomic reduction. There are also a number of genes shared by the two genomes that appear to be fragmenting and possibly represent a snapshot of genomic reduction. Genomic reduction has been hypothesized and described previously for a comparison of the genomes of R. conorii and R. prowazekii (26). Here we identified an apparently similar process in the genomes of strains belonging to the same species, R. rickettsii.

FIG. 4.

Evidence of genomic reduction in R. rickettsii Sheila Smith: graphic representation of the genomic region deleted from R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. The region deleted from R. rickettsii Sheila Smith is indicated by black arrows. CoA, coenzyme A.

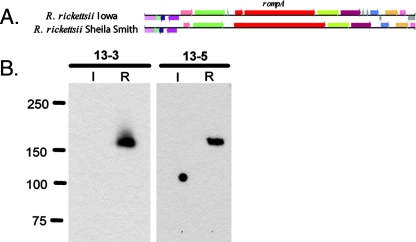

rOmpA is disrupted in R. rickettsii Iowa.

Comparison of R. rickettsii Iowa to R. rickettsii Sheila Smith revealed two deletions in rompA (RrIowa1460), a 1-bp deletion that introduces a stop codon truncating rompA 660 bp from the start codon and an 891-bp in-frame deletion located within the repeat region of rompA (Fig. 5A). rOmpA is one of the major outer membrane proteins found in R. rickettsii and is believed to contribute to virulence (15, 24). To test for the presence of rOmpA in R. rickettsii Iowa, Western blotting was performed with purified R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R using rOmpA-specific monoclonal antibodies (2) (Fig. 5B). No full-length rOmpA or any truncated rOmpA products were detected in R. rickettsii Iowa, whereas a single rOmpA band was detected in R. rickettsii strain R. Immunofluorescence confirmed the absence of rOmpA in R. rickettsii Iowa (data not shown). These results suggest that the 1-bp deletion causes a truncation in rompA as no full-length rOmpA was detected in R. rickettsii Iowa, and they suggest that the truncated product was either rapidly degraded or not detected by our monoclonal antibodies.

FIG. 5.

rOmpA is disrupted in R. rickettsii Iowa. (A) Graphic representation of the disrupted rompA gene in R. rickettsii Iowa. (B) Equal amounts of R. rickettsii Iowa (lanes I) and R. rickettsii strain R (lanes R) were loaded and run on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. rOmpA was detected using monoclonal antibodies 13-3 and 13-5 (2).

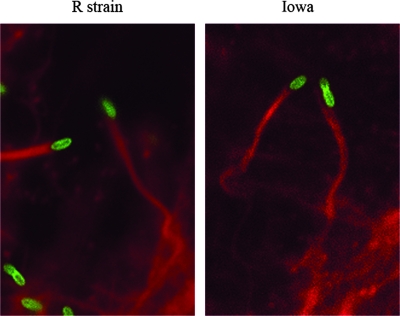

R. rickettsii Iowa has actin-based motility.

R. rickettsii relies on actin-based motility to propel itself from one host cell to another. It has recently been suggested that rOmpA may play a role in the actin-based motility of rickettsiae (7). RickA has previously been shown to be involved in the actin-based motility of rickettsiae (16, 22), but there is a 39-bp in-frame deletion in the gene in R. rickettsii Iowa. Taken together, these two observations suggested that R. rickettsii Iowa may have a defect in its actin-based motility. To determine if the mutations affected the actin-based motility of R. rickettsii Iowa, we confirmed that R. rickettsii Iowa was able to form actin tails during infection of Vero cells. On day 1 after infection no difference in the abilities of R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R to form actin tails was observed (Fig. 6). The ability to form actin tails was also investigated on days 2 and 3 postinfection, and no difference was observed (data not shown). Furthermore, the plaque sizes were indistinguishable, suggesting that the rates of cell-to-cell spread were similar (18). These data are consistent with previous data (20) and suggest that the mutation in rOmpA and the in-frame deletion in RickA do not affect the ability of R. rickettsii Iowa to form actin tails.

FIG. 6.

R. rickettsii Iowa shows normal actin tail formation. Monolayers of Vero cells were infected with either R. rickettsii Iowa or R. rickettsii strain R and allowed to grow for 1 day. R. rickettsii was detected using monoclonal antibody 13-2 (1/100), while F-actin was labeled with rhodamine phalloidin (10 U/ml).

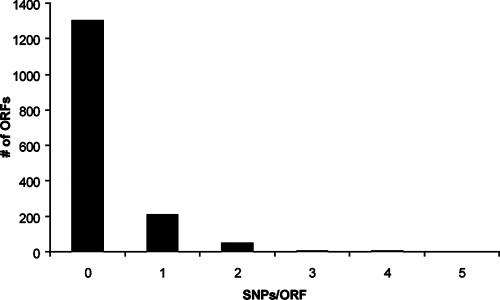

SNP analysis.

To further analyze the genomic differences between R. rickettsii Sheila Smith and R. rickettsii Iowa, SNPs were identified. When R. rickettsii Iowa was compared to R. rickettsii Sheila Smith, only 492 SNPs were identified in the two genomes. Of the 492 SNPs, 5 localized to RNA-encoding regions, 148 were located in intergenic regions, and 339 were found in predicted ORFs. For the ORFs identified as ORFs containing SNPs, only 188 SNPs resulted in nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions. Figure 7 shows the number of SNPs per ORF in the 1,302 ORFs shared by R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. Of the ORFs containing SNPs, only six contain more than two nonsynonymous SNPs (Table 4). One of the genes with multiple SNPs (four SNPs) is rompB, which has previously been shown to be defective in processing in R. rickettsii Iowa (18). This suggests that one or more of the SNPs could be involved in interfering with the ability of the organism to process rOmpB.

FIG. 7.

SNPs present in R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. The numbers of SNPs found in specific ORFs are indicated on the x axis. The total numbers of SNPs/ORF are indicated on the y axis.

TABLE 4.

ORFs containing more that two nonsynonymous SNPs

| ORF | No. of SNPs | Function |

|---|---|---|

| RrIowa0140 | 4 | Hypothetical autotransporter |

| RrIowa0569 | 4 | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase chain A |

| RrIowa0804 | 4 | Biotin operon repressor |

| RrIowa1264 | 4 | rOmpB |

| RrIowa0300 | 3 | Transpeptidase-transglycosylase PBP 1C |

| RrIowa0177 | 3 | Channel protein VirB6 |

Expression analysis of R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R.

Of the 143 deletions and 492 SNPs found in R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith, 96 deletions and 148 SNPs were located in intergenic regions. To study the effect of both intergenic and intragenic mutations on gene expression, custom Affymetrix GeneChips were used to determine gene expression differences between R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R. To determine differences in gene expression, R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R were grown in Vero cells for 3 days (∼2.0 × 106 PFU) before RNA was harvested and hybridized to microarrays. The data indicate that the expression of only four genes was significantly different in R. rickettsii strain R and R. rickettsii Iowa. Thus, the majority of the genetic differences do not affect gene expression (Table 5). Of the four genes that differ in expression, two have differences in the predicted promoter regions and two have 1-bp deletions that result in truncation of the gene.

TABLE 5.

Expression differences between R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R

| Gene | Fold change | Mutation |

|---|---|---|

| RrIowa1459 | −2.7 | 1-bp deletion introduces stop codon |

| RrIowa1486 | −3.1 | Contains two SNPs in potential promoter region |

| RrIowa0791 | −4.3 | 1-bp deletion introduces stop codon |

| RrIowa0614 | 2.5 | 14-bp deletion in potential promoter region |

R. rickettsii Iowa provides protection against R. rickettsii Sheila Smith challenge.

To determine if guinea pigs infected with R. rickettsii Iowa developed immunity against subsequent challenge with virulent R. rickettsii, naïve guinea pigs and guinea pigs that had previously been infected with 1,000 PFU of R. rickettsii Iowa or Sheila Smith and vaccinated with equivalent amounts of paraformaldehyde-fixed R. rickettsii strain R were challenged 30 days after the primary infection with 1,000 PFU of R. rickettsii Sheila Smith. All of the naïve guinea pigs and the guinea pigs inoculated with formalin-killed rickettsiae developed fever after challenge with R. rickettsii Sheila Smith, suggesting that the equivalent of 1,000 PFU of formalin-killed rickettsiae was insufficient to elicit protection against challenge with R. rickettsii Sheila Smith (Table 6). However, all of the guinea pigs infected with R. rickettsii Sheila Smith and four of five guinea pigs infected with R. rickettsii Iowa were protected against challenge with R. rickettsii Sheila Smith (Table 6). One of the R. rickettsii Iowa-vaccinated guinea pigs failed to protect against challenge with R. rickettsii Sheila Smith because it did not develop a detectable antibody response. These results suggest that R. rickettsii Iowa is able to replicate after infection and stimulate an immune response that protects against challenge with R. rickettsii Sheila Smith.

TABLE 6.

R. rickettsii Iowa protects against challenge with R. rickettsii Sheila Smith

| Infection | Challenge | No. of guinea pigs with fever/total no. | Antibody titer (range)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sheila Smith | Sheila Smith | 0/5 | 10,880 (3,200-12,800) |

| Iowa | Sheila Smith | 1/5 | 3,072 (0-12,800) |

| Formalin killed | Sheila Smith | 4/4 | 0 (0) |

| Naïve | Sheila Smith | 5/5 | 0 (0) |

Antibody titers were determined 30 days after vaccination.

DISCUSSION

Strains of R. rickettsii vary dramatically in their virulence in animal model systems and in the severity of human disease that they cause (1, 3, 4, 11, 30). The obligate intracellular lifestyle of rickettsiae and the lack of tractable genetic systems make it difficult to identify genes involved in virulence. With the completed sequences of multiple rickettsial species, it has become possible to investigate differences between virulent and avirulent strains of rickettsiae through comparative genomics. To determine genomic differences between virulent and avirulent strains of R. rickettsii, the sequence of the avirulent strain R. rickettsii Iowa was determined and compared to that of the virulent strain R. rickettsii Sheila Smith.

Both multilocus sequence alignment and genomic comparison of R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith confirmed that these two strains are very closely related. Only two major lesions resulting in gene deletions were found in the two strains (Table 2). Both of these deletions are in R. rickettsii Sheila Smith, as well as the virulent R strain of R. rickettsii, based on microarray analysis of the two genomes. However, the genes in both of the regions appear to be undergoing degradation in R. rickettsii Iowa. This indicates that these regions may not be essential for survival of the organism in either the host or the vector and that in virulent R. rickettsii these genes have been deleted. Genomic reduction in rickettsiae has been described previously (26), and the deletion of genes revealed by a comparison of R. rickettsii Sheila Smith and R. rickettsii Iowa is consistent with this hypothesis.

A 1-bp deletion in the 5′ end of R. rickettsii Iowa rompA introduces a stop codon at amino acid 184 resulting in a premature stop in translation. As a result of this 1-bp deletion, R. rickettsii Iowa does not produce rOmpA. rOmpA has previously been implicated in attachment of R. rickettsii to host cells (24). However, no change in the efficiency of plating or growth rate of R. rickettsii Iowa in the Vero or ISE6 cell line was observed compared to the results for virulent R. rickettsii (data not shown). This suggests that rOmpA is not absolutely required for adherence and entry of R. rickettsii in vitro. rOmpB, which is defective in processing but is still present in the outer membrane of R. rickettsii Iowa, has been shown to interact with host cell protein KU70 to promote entry of R. rickettsii (24a). This interaction, in the absence of rOmpA, may be sufficient for adherence and uptake of R. rickettsii Iowa in vitro. However, the possibility that interactions mediated by rOmpA or rOmpB do play a significant role in infection by R. rickettsii cannot be ruled out as R. rickettsii Iowa was unable to induce fever in guinea pigs.

As previously shown (18), R. rickettsii Iowa is deficient in the processing of rOmpB from the 168-kDa precursor form into the 120- and 32-kDa forms of the protein. In a comparison of the genomes of R. rickettsii Sheila Smith and R. rickettsii Iowa, there were no obvious lesions that accounted for the defect in processing. A direct sequence alignment of the rOmpB proteins from R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith showed that there were four nonsynonymous changes in rOmpB from R. rickettsii Iowa. It is possible that one or more of these changes disrupt the processing of rOmpB. A more detailed site-specific mutation strategy using a heterologous Escherichia coli expression system may prove to be essential for determining if any of these changes contribute to the defect in processing of rOmpB in R. rickettsii Iowa.

Both intergenic and intragenic deletions were found when R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith were compared. There were also a number of SNPs in the two strains that were located in intergenic regions. Any of these differences could lead to altered gene expression. In a comparison of the gene expression levels in R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii strain R, we determined that four genes exhibited significant changes in expression (not including deleted genes). One of these genes was rompA, which has been divided into two ORFs because of a 1-bp deletion. Microarray analysis showed that the expression of the 3′ ORF of rompA (RrIowa1459) in R. rickettsii Iowa was reduced compared to the expression of R. rickettsii strain R rompA. We hypothesize that this could be due to stalling of the ribosomes and disengagement of mRNA at the premature stop codon, thereby causing destabilization of the 3′ half of the message. A result of this destabilization may be an increased rate of degradation of the 3′ region of rompA, decreasing the signal for rompA (RrIowa1459) in R. rickettsii Iowa. A second gene in R. rickettsii Iowa (RrIowa0791) that is split by a premature stop codon shows a similar effect, with the 3′ end of the gene displaying down regulation compared to the R. rickettsii strain R gene. However, most of the genomic differences between R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith do not appear to affect gene expression.

It is apparent that in addition to the processing defect in rOmpB, R. rickettsii Iowa is also deficient in rOmpA. This leads to defects in two of the major factors thought to be involved in the virulence of R. rickettsii. In the absence of methods to genetically manipulate rickettsiae, it would be of great interest to isolate clonal variants which are defective in either rOmpB or rOmpA to test the effect of each mutation on virulence individually. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the differences between R. rickettsii Iowa and R. rickettsii Sheila Smith are not limited to rOmpB and rOmpA. However, without a good genetic system available, comparison of multiple genomes of virulent and avirulent isolates may prove to be the most expedient method to identify bacterial factors that play a role in the pathogenesis of R. rickettsii.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Heinzen and B. Kleba for critical reviews of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anacker, R. L., R. H. List, R. E. Mann, and D. L. Wiedbrauk. 1986. Antigenic heterogeneity in high- and low-virulence strains of Rickettsia rickettsii revealed by monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 51653-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anacker, R. L., R. E. Mann, and C. Gonzales. 1987. Reactivity of monoclonal antibodies to Rickettsia rickettsii with spotted fever and typhus group rickettsiae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25167-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anacker, R. L., T. F. McCaul, W. Burgdorfer, and R. K. Gerloff. 1980. Properties of selected rickettsiae of the spotted fever group. Infect. Immun. 27468-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anacker, R. L., R. N. Philip, J. C. Williams, R. H. List, and R. E. Mann. 1984. Biochemical and immunochemical analysis of Rickettsia rickettsii strains of various degrees of virulence. Infect. Immun. 44559-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson, S. G., and C. G. Kurland. 1998. Reductive evolution of resident genomes. Trends Microbiol. 6263-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson, S. G., A. Zomorodipour, J. O. Andersson, T. Sicheritz-Ponten, U. C. Alsmark, R. M. Podowski, A. K. Naslund, A. S. Eriksson, H. H. Winkler, and C. G. Kurland. 1998. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldridge, G. D., N. Y. Burkhardt, J. A. Simser, T. J. Kurtti, and U. G. Munderloh. 2004. Sequence and expression analysis of the ompA gene of Rickettsia peacockii, an endosymbiont of the Rocky Mountain wood tick, Dermacentor andersoni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 706628-6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, H. R. 1941. Cultivation of rickettsiae of the Rocky Mountain spotted fever, typhus and Q fever groups in the embryonic tissues of developing chicks. Science 94399-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darling, A. C., B. Mau, F. R. Blattner, and N. T. Perna. 2004. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 141394-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DelVecchio, V. G., V. Kapatral, R. J. Redkar, G. Patra, C. Mujer, T. Los, N. Ivanova, I. Anderson, A. Bhattacharyya, A. Lykidis, G. Reznik, L. Jablonski, N. Larsen, M. D'Souza, A. Bernal, M. Mazur, E. Goltsman, E. Selkov, P. H. Elzer, S. Hagius, D. O'Callaghan, J. J. Letesson, R. Haselkorn, N. Kyrpides, and R. Overbeek. 2002. The genome sequence of the facultative intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99443-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eremeeva, M. E., G. A. Dasch, and D. J. Silverman. 2001. Quantitative analyses of variations in the injury of endothelial cells elicited by 11 isolates of Rickettsia rickettsii. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8788-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eremeeva, M. E., R. M. Klemt, L. A. Santucci-Domotor, D. J. Silverman, and G. A. Dasch. 2003. Genetic analysis of isolates of Rickettsia rickettsii that differ in virulence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 990717-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge, H., Y. Y. Chuang, S. Zhao, M. Tong, M. H. Tsai, J. J. Temenak, A. L. Richards, and W. M. Ching. 2004. Comparative genomics of Rickettsia prowazekii Madrid E and Breinl strains. J. Bacteriol. 186556-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillespie, J. J., M. S. Beier, M. S. Rahman, N. C. Ammerman, J. M. Shallom, A. Purkayastha, B. S. Sobral, and A. F. Azad. 2007. Plasmids and rickettsial evolution: insight from Rickettsia felis. PLoS ONE 2e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilmore, R. D., Jr., and T. Hackstadt. 1991. DNA polymorphism in the conserved 190 kDa antigen gene repeat region among spotted fever group rickettsiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 109777-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gouin, E., C. Egile, P. Dehoux, V. Villiers, J. Adams, F. Gertler, R. Li, and P. Cossart. 2004. The RickA protein of Rickettsia conorii activates the Arp2/3 complex. Nature 427457-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hackstadt, T. 1996. The biology of rickettsiae. Infect. Agents Dis. 5127-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hackstadt, T., R. Messer, W. Cieplak, and M. G. Peacock. 1992. Evidence for proteolytic cleavage of the 120-kilodalton outer membrane protein of rickettsiae: identification of an avirulent mutant deficient in processing. Infect. Immun. 60159-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hand, W. L., J. B. Miller, J. A. Reinarz, and J. P. Sanford. 1970. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. A vascular disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 125879-882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinzen, R. A., S. F. Hayes, M. G. Peacock, and T. Hackstadt. 1993. Directional actin polymerization associated with spotted fever group Rickettsia infection of Vero cells. Infect. Immun. 611926-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivanova, N., A. Sorokin, I. Anderson, N. Galleron, B. Candelon, V. Kapatral, A. Bhattacharyya, G. Reznik, N. Mikhailova, A. Lapidus, L. Chu, M. Mazur, E. Goltsman, N. Larsen, M. D'Souza, T. Walunas, Y. Grechkin, G. Pusch, R. Haselkorn, M. Fonstein, S. D. Ehrlich, R. Overbeek, and N. Kyrpides. 2003. Genome sequence of Bacillus cereus and comparative analysis with Bacillus anthracis. Nature 42387-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeng, R. L., E. D. Goley, J. A. D'Alessio, O. Y. Chaga, T. M. Svitkina, G. G. Borisy, R. A. Heinzen, and M. D. Welch. 2004. A Rickettsia WASP-like protein activates the Arp2/3 complex and mediates actin-based motility. Cell. Microbiol. 6761-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapatral, V., I. Anderson, N. Ivanova, G. Reznik, T. Los, A. Lykidis, A. Bhattacharyya, A. Bartman, W. Gardner, G. Grechkin, L. Zhu, O. Vasieva, L. Chu, Y. Kogan, O. Chaga, E. Goltsman, A. Bernal, N. Larsen, M. D'Souza, T. Walunas, G. Pusch, R. Haselkorn, M. Fonstein, N. Kyrpides, and R. Overbeek. 2002. Genome sequence and analysis of the oral bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum strain ATCC 25586. J. Bacteriol. 1842005-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, H., and D. H. Walker. 1998. rOmpA is a critical protein for the adhesion of Rickettsia rickettsii to host cells. Microb. Pathog. 24289-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Martinez, J. J., S. Seveau, E. Veiga, S. Matsuyama, and P. Cossart. 2005. Ku70, a component of DNA-dependent protein kinase, is a mammalian receptor for Rickettsia conorii. Cell 1231013-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLeod, M. P., X. Qin, S. E. Karpathy, J. Gioia, S. K. Highlander, G. E. Fox, T. Z. McNeill, H. Jiang, D. Muzny, L. S. Jacob, A. C. Hawes, E. Sodergren, R. Gill, J. Hume, M. Morgan, G. Fan, A. G. Amin, R. A. Gibbs, C. Hong, X. J. Yu, D. H. Walker, and G. M. Weinstock. 2004. Complete genome sequence of Rickettsia typhi and comparison with sequences of other rickettsiae. J. Bacteriol. 1865842-5855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogata, H., S. Audic, P. Renesto-Audiffren, P. E. Fournier, V. Barbe, D. Samson, V. Roux, P. Cossart, J. Weissenbach, J. M. Claverie, and D. Raoult. 2001. Mechanisms of evolution in Rickettsia conorii and R. prowazekii. Science 2932093-2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogata, H., B. La Scola, S. Audic, P. Renesto, G. Blanc, C. Robert, P. E. Fournier, J. M. Claverie, and D. Raoult. 2006. Genome sequence of Rickettsia bellii illuminates the role of amoebae in gene exchanges between intracellular pathogens. PLoS Genet. 2e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogata, H., P. Renesto, S. Audic, C. Robert, G. Blanc, P. E. Fournier, H. Parinello, J. M. Claverie, and D. Raoult. 2005. The genome sequence of Rickettsia felis identifies the first putative conjugative plasmid in an obligate intracellular parasite. PLoS Biol. 3e248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Overbeek, R., N. Larsen, T. Walunas, M. D'Souza, G. Pusch, E. Selkov, Jr., K. Liolios, V. Joukov, D. Kaznadzey, I. Anderson, A. Bhattacharyya, H. Burd, W. Gardner, P. Hanke, V. Kapatral, N. Mikhailova, O. Vasieva, A. Osterman, V. Vonstein, M. Fonstein, N. Ivanova, and N. Kyrpides. 2003. The ERGO genome analysis and discovery system. Nucleic Acids Res. 31164-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price, W. H. 1953. The epidemiology of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. I. The characterization of strain virulence of Rickettsia rickettsii. Am. J. Hyg. 58248-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricketts, H. T. 1907. Further experiments with the woodtick in relation to Rocky Mountain spotted fever. JAMA 491278-1281. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voyich, J. M., K. R. Braughton, D. E. Sturdevant, A. R. Whitney, B. Said-Salim, S. F. Porcella, R. D. Long, D. W. Dorward, D. J. Gardner, B. N. Kreiswirth, J. M. Musser, and F. R. DeLeo. 2005. Insights into mechanisms used by Staphylococcus aureus to avoid destruction by human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 1753907-3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss, E., J. C. Coolbaugh, and J. C. Williams. 1975. Separation of viable Rickettsia typhi from yolk sac and L cell host components by renografin density gradient centrifugation. Appl. Microbiol. 30456-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]