Abstract

Listeriolysin O (LLO), the pore-forming toxin of Listeria monocytogenes, is a prototype of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) secreted by several pathogenic and nonpathogenic gram-positive bacteria. In addition to mediating the escape of the bacterium into the cytosol, this toxin is generally believed to be a central player in host-pathogen interactions during L. monocytogenes infection. LLO triggers the influx of Ca2+ into host cells as well as the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Thus, many of the cellular responses induced by LLO are related to calcium signaling. Interestingly, in this study, we report that prolonged exposure to LLO desensitizes cells to Ca2+ mobilization upon subsequent stimulations with LLO. Cells preexposed to LLO-positive L. monocytogenes but not to the LLO-deficient Δhly mutant were found to be highly refractory to Ca2+ induction in response to receptor-mediated stimulation. Such cells also exhibited diminished Ca2+ signals in response to stimulation with LLO and thapsigargin. The presented results suggest that this phenomenon is due to the depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. The ability of LLO to desensitize immune cells provides a significant hint about the possible role played by CDCs in the evasion of the immune system by bacterial pathogens.

The gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is responsible for the disease listeriosis, which is acquired mainly by ingesting contaminated food. The main virulence factor of this facultative, intracellular bacterial pathogen is the pore-forming toxin listeriolysin O (LLO), which plays a crucial role during its complicated intracellular life cycle. First, LLO enables the bacterium to breach membrane barriers. Additionally, LLO acts as a pseudocytokine/chemokine with which the bacterium communicates and influences various host cells during infection. For instance, LLO can influence the outcome of an infection via the modulation of bacterial entry into cells (9, 31, 32) and the induction of apoptosis (5, 6), as well as the synthesis and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines (21, 22, 29, 30).

The induction of calcium signals plays an important role for effector cells of the immune system. Several studies have shown that this ubiquitous signaling pathway can be hijacked by bacterial pathogens to promote their survival in the host. L. monocytogenes is one such pathogen. Many of the host responses triggered by LLO involve Ca2+ signaling (15, 31, 32). Although calcium signal induction by L. monocytogenes is a complex process that involves more than one virulence factor, several independent studies indicate that LLO is the sine qua non of Ca2+ mobilization (14, 25, 26, 31). This is exemplified by the fact that the Δhly mutant strain of L. monocytogenes, which lacks LLO, is incapable of eliciting any Ca2+ response in host cells (14, 25, 31). The mechanisms by which LLO promotes Ca2+ signal induction by L. monocytogenes are manifold. LLO makes membrane pores permissible to ions and macromolecules. Thus, during infection, LLO secreted by the bacterium not only allows an influx of Ca2+ into host cells but also allows the listerial phosphatases phospholipase C A (PLCA) and PLCB to access their intracellular substrates, hence causing Ca2+ to be released from intracellular stores (25, 31). Irrespective of that, LLO alone can directly cause Ca2+ to be released from intracellular stores via multiple mechanisms (14).

Paradoxically, in this study we show that prolonged exposure of cells to LLO or L. monocytogenes renders them inert to Ca2+ induction upon subsequent stimulations. We demonstrate that this phenomenon is due to the depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. A role for this phenomenon might lie in the subversion of various effector cells of the immune system during L. monocytogenes infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and bacterial strains.

Either the wild-type L. monocytogenes strain EGD-e or its LLO-deficient Δhly derivative were used. Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), and Ca2+-free DMEM were obtained from Gibco (Karlsruhe, Germany). LLO was purified from overexpressing Listeria innocua, as described previously (7). Indo 1-AM, ionomycin, and thapsigargin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Antibodies against 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP)-bovine serum albumin immunoglobulin E (IgE) and DNP-bovine serum albumin were kindly provided by Pecht I (The Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel).

Cells.

Bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) were matured by culturing bone marrow cells in the presence of interleukin-3 for 4 to 8 weeks, as described previously (14), while T cells were freshly isolated from the spleens of hemagglutinin-T-cell receptor RAG1−/− mice.

Preexposure of cells to bacteria or LLO.

Cells were cultured with L. monocytogenes or the Δhly mutant (multiplicity of infection, 100) or treated with LLO (0.25 μg/ml) for various time periods (3 to 48 h), washed, and then labeled with Indo 1-AM, as described below. It should be noted that the above-mentioned concentration of LLO was used in all the experiments described in this study. The concentration of LLO used in our studies was chosen following a careful titration in which it was found to be the optimal dose that triggers signals such as protein tyrosine phosphorylation and calcium signaling without killing cells (12-14).

Ca2+ measurements by flow cytometry.

A total of 5 × 106 BMMCs in 500 μl DMEM were incubated with 50 μM Indo 1-AM in complete medium at 37°C. After 45 min, the cells were washed once in Ca2+-free medium supplemented with 10 mM EGTA to ensure the removal of any residual extracellular calcium from cells and then twice in unsupplemented Ca2+-free medium to remove any residual EGTA. This second step was necessary since the influx of residual EGTA into the cell via the LLO pore could chelate intracellular Ca2+, hence marring the Ca2+ signals due to the release of Ca2+ from the intracellular stores. Therefore, to evaluate the relative contributions of extracellular and intracellular Ca2+ pools to the overall Ca2+ signals triggered by LLO, after this washing procedure, cells were resuspended in either normal or Ca2+-free medium and then kept on ice until they were ready for measurement. The cells were warmed up to 37°C before the start of the Ca2+ measurements. All measurements were carried out in a MoFlo high-speed cell sorter (DakoCytomation) equipped with a UV argon ion laser (351 to 363 nm). Indo 1-AM emissions were detected with fluorescence filters with excitation/emission bandwidths of 405/30 nm (Ca2+-bound Indo 1-AM) and 515/30 nm (Ca2+-free Indo 1-AM) (F405/30 and F515/30, respectively). First, the ratio of the fluorescence emitted at the two Indo 1-AM excitation emission wavelengths (F405/30 to F515/30) was calculated and then calibrated into arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU) by the equation F405/30 divided by F515/30 times 128, where the constant 128 is the median of the instrument's fluorescence spectrum. The data were subsequently normalized for fluctuations in the initial baseline measurements with Excel software by dividing all the AFU with the average AFU of the initial 30-s baseline period. Therefore, the arbitrary ratiometric units represent the increase in the value for F405/30 divided by the value for F515/30 over that of the initial baseline.

RESULTS

L. monocytogenes and LLO render mast cells unresponsive to antigen-induced calcium signaling.

In the present study, we used mainly mast cells as a model target cell type for L. monocytogenes. Mast cells have a wide tissue distribution, especially at host-environment interfaces, such as the skin, airways, and gastrointestinal tract, where pathogens and other environmental agents are frequently encountered. As such, they represent the first host cell type that most likely encounters pathogens when they cross epithelia, like the intestinal barrier. Indeed, the role of mast cells in listeriosis is now well established (10, 11).

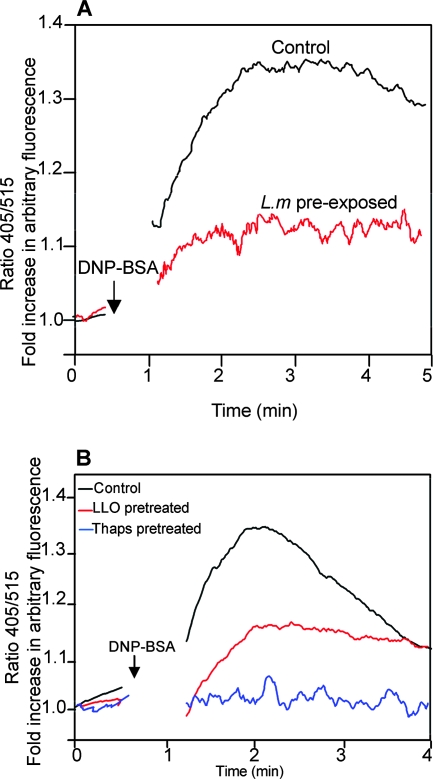

The classical activation of mast cells occurs via the immunoglobulin-E-dependent cross-linking of high-affinity Fcɛ receptor I (FcɛRI) when an antigen is encountered. One of the early events triggered via an antigen receptor in such cells is Ca2+ mobilization. This involves an initial release from the intracellular stores, which in turn triggers an influx via the plasma membrane channels. In a previous study, we demonstrated that one of the immediate cellular responses triggered by L. monocytogenes or LLO upon contact with target host cells is intracellular Ca2+ mobilization (14). Paradoxically, when mast cells that had been subjected to prolonged exposure to L. monocytogenes or LLO were stimulated with antigen, such cells appeared to be highly unresponsive to Ca2+ mobilization (Fig. 1A and B). Consistently, no signal was elicited in cells pretreated with thapsigargin, a compound that depletes intracellular Ca2+ stores. These results suggested that although L. monocytogenes and LLO can trigger Ca2+ signals, sustained exposure of cells to these agents could have the reverse effect since the agents interfere with subsequent receptor-mediated Ca2+ induction.

FIG. 1.

L. monocytogenes (L.m) and LLO renders BMMCs inert to antigen-induced Ca2+ mobilization. (A) BMMCs were exposed to L. monocytogenes and loaded with Indo 1-AM and then incubated on ice with an IgE antibody specific for DNP. After the unbound antibody was washed off, cells were stored on ice. When ready for calcium measurements, cells were warmed up to 37°C before DNP-bovine serum albumin (BSA) was added to cross-link the FcɛRI. Stimulation was done in a Ca2+-containing medium. (B) BMMCs were left untreated or pretreated with LLO (0.25 μg/ml/ml) or thapsigargin (Thaps) (1 μM) for 4 h, loaded with Indo 1-AM, and then stimulated via FcɛRI as described for panel A. Each trace represents the average of intracellular Ca2+ levels in the cells during the time of acquisition. A 30-s baseline was recorded each time before stimulation. The arrows indicate the time points of stimulation. The experiment was repeated at least three times with similar results.

In view of the role of LLO, next we considered the potential mechanism by which this toxin could impose Ca2+ unresponsiveness in host cells. LLO can trigger cellular responses via pore-dependent and pore-independent mechanisms (12). The cholesterol inactivation of LLO blocks the pore-dependent but not the pore-independent mechanism. In contrast to cells exposed to LLO, cells exposed to cholesterol-inactivated LLO did not exhibit the refractory Ca2+ signaling (data not shown). This indicated that the above-described phenomenon was dependent on the pore-forming activity of LLO.

L. monocytogenes- or LLO-pretreated cells exhibit resistance to calcium induction by LLO.

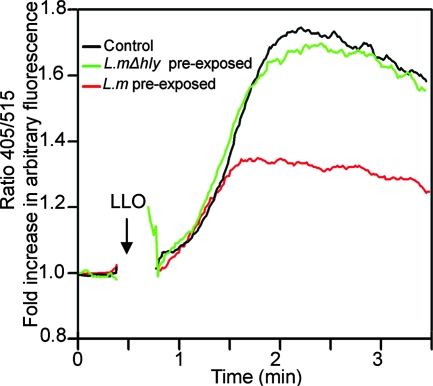

Since LLO itself induces calcium signals (14, 25), we also tested whether pretreatment with L. monocytogenes also affects LLO-induced calcium signals. BMMCs were preexposed to L. monocytogenes or the LLO-deficient Δhly mutant for 4 h before we analyzed the induction of calcium fluxes by LLO. As shown in Fig. 2, cells preexposed to L. monocytogenes but not the Δhly mutant became highly refractory to calcium signals induced by LLO. Thus, the reduced calcium signaling in host cells that were preexposed to L. monocytogenes is not specific for the cross-linkage of FcɛRI but applies to other Ca2+ mobilization agonists.

FIG. 2.

Preincubation with L. monocytogenes (L.m) renders cells resistant to LLO-induced calcium signals. After incubation with (or without) L. monocytogenes or the LLO-deficient L. monocytogenes Δhly mutant (L.mΔhly) (multiplicity of infection, 100) for 3 h, BMMCs were washed and then loaded with Indo 1-AM in penicillin-streptomycin-supplemented medium for 45 min (to kill all the bacteria). Cells were again washed and then suspended in Ca2+-containing medium and analyzed by flow cytometry for intracellular Ca2+ mobilization following stimulation with LLO (0.25 μg/ml). The arrow indicates the time point of stimulation. The experiment was repeated at least three times with similar results.

Resistance to calcium induction in L. monocytogenes- or LLO-pretreated cells is not due to an influx of extracellular Ca2+ but due to the depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores.

The overall amplitude of calcium signals induced via FcɛRI or LLO is a product of Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores as well as an influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular milieu (14, 18, 20). From the above-described experiments, it was not certain whether the refractory Ca2+ responses in L. monocytogenes- or LLO-pretreated cells were due to a diminished Ca2+ influx or a release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores.

Pore-forming agents have been reported to render cells resistant to subsequent membrane perforation (24). Since LLO-mediated Ca2+ influx is due to the pore-forming activity of the toxin, whether the refractory phenomenon in L. monocytogenes- or LLO-pretreated cells was due to the LLO-induced resistance of host cells to membrane perforation was considered. To that end, control and LLO-pretreated cells were evaluated for their capacity to take up propidium iodide (PI). PI is a DNA-binding fluorescent dye which permeates the cell only in the event of membrane damage. Control and LLO-pretreated cells exhibited comparable levels of PI uptake upon subsequent treatment with LLO (data not shown). As already reported in our recent study (14), it is worth mentioning that, despite permeabilization, over time, more than 75 to 80% of such cells showed recovery and became impermeant to PI (reference 14 and data not shown). Thus, resistance to perforation was ruled out as the cause of the diminished Ca2+ responses in L. monocytogenes- or LLO-preexposed cells.

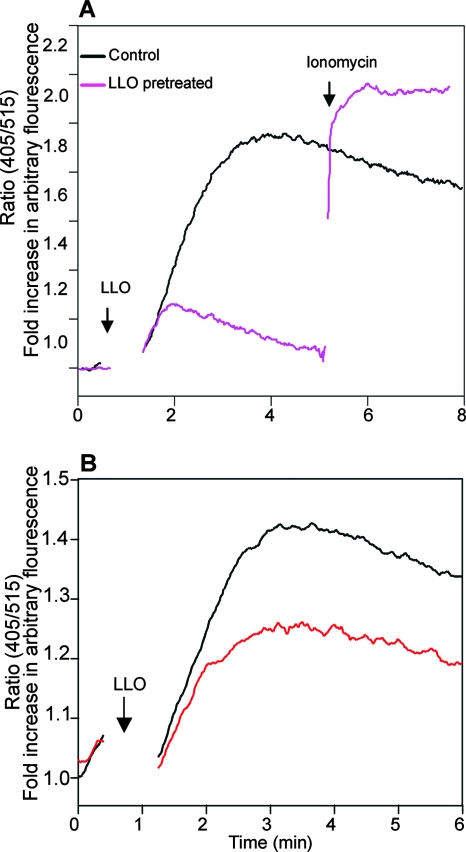

As a control, we also evaluated the effect of LLO pretreatment on ionophore-mediated Ca2+ influx. Whereas cells pretreated with LLO showed a profound impairment in LLO-induced intracellular Ca2+ elevation, as expected, such cells were still highly responsive to ionomycin-induced Ca2+ mobilization (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

LLO-pretreated cells exhibit diminished intracellular Ca2+ release but respond normally to ionophore-mediated Ca2+ influx. (A) Pretreated cells are refractory to LLO but not to ionomycin-mediated Ca2+ mobilization. BMMCs were pretreated (or not) with LLO (0.25 μg/ml) for 3 h, loaded with Indo 1-AM, and resuspended in Ca2+-containing medium. LLO was added to such cells at the time point indicated by the arrow marked “LLO,” and intracellular Ca2+ was measured. At the time point indicated by the other arrow, 1 μM ionomycin was added. (B) LLO-induced Ca2+ responses in pretreated cells under Ca2+-free conditions. BMMCs were incubated with (or without) LLO (0.25 μg/ml) for 4 h and then loaded with Indo 1-AM. To evaluate only the Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores, cells were thoroughly washed in Ca2+-free medium and then resuspended in Ca2+-free medium before stimulation with LLO (0.25 μg/ml) at the time point indicated by the arrow.

To determine whether the refractory Ca2+ responses were due to a diminished Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, cells were pretreated with LLO and tested under Ca2+-free conditions. As shown in Fig. 3B, LLO-pretreated cells also exhibited diminished calcium responses under such conditions. Together, these data suggest that L. monocytogenes or LLO pretreatment affects mainly the intracellular release of Ca2+ and not its influx from the extracellular medium.

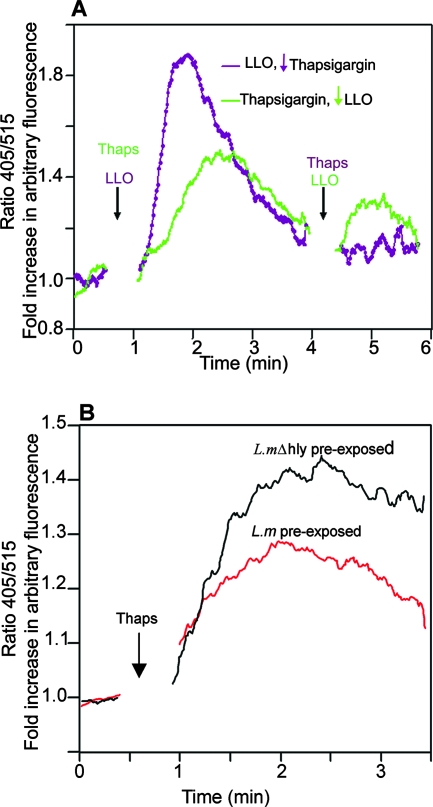

To confirm this possibility, we opted to employ thapsigargin, the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor, which depletes intracellular calcium stores by causing an unregulated efflux of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. The treatment of cells with LLO led to a strong elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ that rapidly dropped to near-basal levels. When such cells were immediately reexposed to thapsigargin so that we could evaluate the Ca2+ level in intracellular stores, hardly any elevation in Ca2+ was induced, an indication that LLO had emptied intracellular Ca2+ stores (Fig. 4A, purple trace).

FIG. 4.

LLO depletes intracellular Ca2+ stores. LLO (0.25 μg/ml) was added to Indo 1-AM-loaded BMMCs, and intracellular Ca2+ was measured. Then, thapsigargin (Thaps; 1 μM) was added to evaluate the remaining Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (purple trace). Vice versa, thapsigargin was first added to cells to achieve maximum Ca2+ release from intracellular stores before the addition of 0.25 μg/ml LLO (green trace). Note that unlike in untreated cells, hardly any Ca2+ was released from intracellular stores by thapsigargin after LLO pretreatment. Ca2+ mobilization induced by LLO was also greatly diminished in thapsigargin-pretreated cells. Since the experiment was done in Ca2+-containing medium, note that the minor peak elicited by LLO in thapsigargin-pretreated cells is most likely due to a Ca2+ influx via the toxin pores. (B) Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by L. monocytogenes (L.m). BMMCs were incubated for 3 h with L. monocytogenes or the Δhly mutant (L.mΔhly) (multiplicity of infection, 100) and then loaded with Indo 1-AM and treated with thapsigargin (1 μM) to evaluate the maximum Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Arrows indicate the time points of additions of LLO and thapsigargin.

Then, the order was reversed and the cells were treated with thapsigargin to deplete intracellular stores before stimulation with LLO. Thapsigargin evoked a strong elevation in cytosolic Ca2+ in untreated cells (Fig. 4A, green trace). The thapsigargin-pretreated cells were highly refractory to calcium induction upon reexposure to LLO (compare the first peak of the purple trace and the second peak of the green trace in Fig. 4A). Since LLO causes a Ca2+ influx from the extracellular pool in addition to the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, it should be noted that, as expected, LLO still caused cytosolic Ca2+ elevation, albeit at low levels, in thapsigargin-pretreated cells. The depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores was also tested following the exposure of cells to live bacteria. Figure 4B shows Ca2+ signals elicited by thapsigargin in cells preincubated for 4 h with L. monocytogenes or the Δhly mutant. As depicted, the release of Ca2+ in cells preexposed to L. monocytogenes was significantly diminished compared to the release of Ca2+ in the Δhly mutant-preexposed cells. Together, these data show that due to an unregulated release of Ca2+, the exposure of cells to L. monocytogenes or its toxin LLO causes the depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores, hence rendering them refractory to intracellular Ca2+ release agonists.

Refractory Ca2+ signals wane with longer periods of toxin exposure.

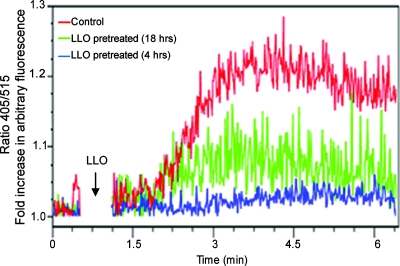

To determine whether the depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by LLO is a property that can be generalized to other cell types, primary T cells were also tested. Untreated and LLO-pretreated T cells were restimulated with LLO in Ca2+-free medium to assess only the Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. As shown before, the intracellular Ca2+ release in cells pretreated with LLO was remarkably lower than the Ca2+ release in untreated cells. Interestingly, almost no measurable calcium release was obtained with T cells that were pretreated with LLO for 4 h, while cells pretreated for 18 h showed a low but definitive Ca2+ signal (Fig. 5). Cells pretreated with LLO for 48 h exhibited a normal response to the induction of Ca2+ by LLO (data not shown). This suggests that calcium depletion by LLO is reversible and that, with time, cells recover from the toxin's effects and restock their intracellular Ca2+ stores. The reversible nature of intracellular Ca2+ depletion by LLO is consistent with our recent findings which suggest that despite the permeabilization and efflux of molecules from the cytosol and the ER, over time, cells exposed to sublytic doses of LLO do indeed repair the membrane lesions, regain normal physiological function, and even proliferate (14). The findings are also consistent with the normal homeostatic regulation of Ca2+ signaling. Sustained Ca2+ elevation can be toxic to the cells. To circumvent this, Ca2+ is rapidly sequestered into the mitochondria and pumped out of the cell by various exchangers and pumps, such as the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase. This probably accounts for the transient depletion of intracellular stores. However, during the recovery process, the sarcoplasmic reticulum/ER Ca2+-ATPase pumps Ca2+ back into the ER, while Ca2+ sequestered in mitochondria is slowly released back into the cytosol, eventually making its way into the ER (3).

FIG. 5.

Refractory Ca2+ signaling wanes with longer periods of toxin exposure. Primary T cells were pretreated (or untreated) with LLO (0.25 μg/ml) for 4 h or 18 h. To evaluate the intracellular Ca2+ stored in such cells, cells were labeled with Indo 1-AM and washed thoroughly as described in Materials and Methods and then resuspended in Ca2+-free medium before they were restimulated with 0.25 μg/ml LLO (the arrow indicates the point of stimulation). It is, however, worth pointing out that with our culture conditions, the indicated T cells showed no appreciable proliferation. Thus, with or without cellular growth, cells do recover from the indicated toxin effects.

DISCUSSION

The modulation of calcium signals is a very important mechanism by which many pathogenic bacteria influence host cells. Alterations of metabolism, activation of apoptosis, and induction of proinflammatory mediators as well as cytoskeletal reorganization have been reported in this context (15, 27, 29, 31, 32). A prominent example of bacterial factors known to participate in bacterium-induced Ca2+ signaling is pore-forming toxins. LLO, a family member of the cholesterol-dependent pore-forming toxins, is well described for its role in various Ca2+-dependent host responses during L. monocytogenes infection (9, 31, 32). In a previous study, we investigated the mechanisms of Ca2+ induction by L. monocytogenes and LLO and the cellular responses triggered therefrom. For instance, with respect to the latter, we showed how Ca2+ signals triggered by LLO activate the transcription and secretion of inflammatory mediators (14). In the present work, we show that the mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores by L. monocytogenes and LLO goes beyond just triggering Ca2+-dependent responses. LLO depletes intracellular Ca2+ stores, hence rendering preexposed cells inert to subsequent Ca2+ inductions by various intracellular Ca2+ release agonists. This is most compellingly demonstrated by the fact that cells pretreated with L. monocytogenes or LLO exhibit highly diminished intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in response to thapsigargin. The thapsigargin experiment clearly shows that preexposure of cells to LLO of L. monocytogenes causes the depletion of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, explaining why such cells become highly resistant to Ca2+ signals, such as those triggered by LLO, or via membrane receptors, such as FcɛRI.

The depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by LLO is most likely attributable to its ability to trigger intracellular Ca2+ release via multiple mechanisms. LLO triggers Ca2+ release via the G protein and protein tyrosine kinase activation of the PLC-inositol triphosphate-regulated Ca2+ channels. Additionally, it causes reversible injury to the intracellular stores, such as the ER and the lysosomes (14). A combination of these effects, probably together with the active extrusion of Ca2+ via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase, could account for the depletion of intracellular stores.

That LLO triggers Ca2+ mobilization in cells and yet renders them inert to subsequent stimuli is an important finding.

Although it is not clear at the moment how this might benefit the pathogen, we are tempted to speculate that refractory induction of calcium signals in host cells may have severe physiological significance in the context of listeriosis. One such possibility is the interference with various Ca2+-dependent cytokines/chemokines or antigen-induced effector functions during L. monocytogenes infection.

For instance, the productive activation of lymphocytes requires a balanced integration of Ca2+ and other signaling pathways. Stimulation of the antigen receptor in the absence of Ca2+ signals leads to a state of anergy or antigen unresponsiveness (1, 2, 23). On the other hand, sustained calcium signaling in the absence of antigen receptor stimulation causes the same unresponsiveness (16, 17, 19). Indeed, when lymphocytes are subjected to a sustained exposure to ionomycin in the absence of antigen stimulation, they become unresponsive to subsequent antigen-induced Ca2+ signals and exhibit an anergic state (16, 17, 19). Thus, it is imaginable that during L. monocytogenes infection, a prior exposure of host lymphocytes to LLO could render such cells unresponsive to antigen stimulation, which would undermine the host's ability to mount an effective immune response, much to the pathogen's advantage. A similar scenario could be envisioned for responsiveness to cytokines or other mediators involving Ca2+ signals.

The use of toxins as an immunosuppressive tool by bacteria to evade the adaptive immune responses is not uncommon. Inhibition of T-lymphocyte activation and proliferation by the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin VacA is a well-established phenomenon (4, 28). Although the mechanisms by which this toxin suppresses T-cell activation are different from those proposed for LLO herein, it is interesting to note that Ca2+ signal induction is a common feature shared by both toxins (8). Additional studies can now be performed to establish whether the ability of LLO to render host cells inert to Ca2+ mobilization is indeed involved in the process by which L. monocytogenes evades the innate and the adaptive immune response.

Our data might therefore have important implications in the understanding of how L. monocytogenes, as well as the other pathogenic gram-positive bacteria which secrete analogous CDCs, circumvents the host defenses in order to establish a niche in the host.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the Deutsche Krebshilfe.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andris, F., M. Van Mechelen, F. De Mattia, E. Baus, J. Urbain, and O. Leo. 1996. Induction of T cell unresponsiveness by anti-CD3 antibodies occurs independently of co-stimulatory functions. Eur. J. Immunol. 261187-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Amor, A., M. Leite-De-Moraes, F. Lepault, E. Schneider, F. Machavoine, A. Arnould, L. Chatenoud, and M. Dy. 1995. Role of interleukin-2 receptors in the suppressive effect of spleen cells from anti-CD3-treated mice. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 6221-224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge, M. J., M. D. Bootman, and H. L. Roderick. 2003. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4517-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boncristiano, M., S. R. Paccani, S. Barone, C. Ulivieri, L. Patrussi, D. Ilver, A. Amedei, M. M. D'Elios, J. L. Telford, and C. T. Baldari. 2003. The Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin inhibits T-cell activation by two independent mechanisms. J. Exp. Med. 1981887-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrero, J. A., B. Calderon, and E. R. Unanue. 2004. Listeriolysin O from Listeria monocytogenes is a lymphocyte apoptogenic molecule. J. Immunol. 1724866-4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrero, J. A., B. Calderon, and E. R. Unanue. 2004. Type I interferon sensitizes lymphocytes to apoptosis and reduces resistance to Listeria infection. J. Exp. Med. 200535-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darji, A., T. Chakraborty, K. Niebuhr, N. Tsonis, J. Wehland, and S. Weiss. 1995. Hyperexpression of listeriolysin in the nonpathogenic species Listeria innocua and high yield purification. J. Biotechnol. 43205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bernard, M., A. Cappon, L. Pancotto, P. Ruggiero, J. Rivera, G. Del Giudice, and C. Montecucco. 2005. The Helicobacter pylori VacA cytotoxin activates RBL-2H3 cells by inducing cytosolic calcium oscillations. Cell. Microbiol. 7191-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dramsi, S., and P. Cossart. 2003. Listeriolysin O-mediated calcium influx potentiates entry of Listeria monocytogenes into the human Hep-2 epithelial cell line. Infect. Immun. 713614-3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelson, B. T., Z. Li, L. K. Pappan, and M. M. Zutter. 2004. Mast cell-mediated inflammatory responses require the alpha 2 beta 1 integrin. Blood 1032214-2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelson, B. T., T. P. Stricker, Z. Li, S. K. Dickeson, V. L. Shepherd, S. A. Santoro, and M. M. Zutter. 2006. Novel collectin/C1q receptor mediates mast cell activation and innate immunity. Blood 107143-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gekara, N. O., T. Jacobs, T. Chakraborty, and S. Weiss. 2005. The cholesterol-dependent cytolysin listeriolysin O aggregates rafts via oligomerization. Cell. Microbiol. 71345-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gekara, N. O., and S. Weiss. 2004. Lipid rafts clustering and signalling by listeriolysin O. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32712-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gekara, N. O., K. Westphal, B. Ma, M. Rohde, L. Groebe, and S. Weiss. 2007. The multiple mechanisms of Ca2+ signalling by listeriolysin O, the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin of Listeria monocytogenes. Cell. Microbiol. 92008-2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldfine, H., and S. J. Wadsworth. 2002. Macrophage intracellular signaling induced by Listeria monocytogenes. Microbes Infect. 41335-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heissmeyer, V., F. Macian, S. H. Im, R. Varma, S. Feske, K. Venuprasad, H. Gu, Y. C. Liu, M. L. Dustin, and A. Rao. 2004. Calcineurin imposes T cell unresponsiveness through targeted proteolysis of signaling proteins. Nat. Immunol. 5255-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heissmeyer, V., F. Macian, R. Varma, S. H. Im, F. Garcia-Cozar, H. F. Horton, M. C. Byrne, S. Feske, K. Venuprasad, H. Gu, Y. C. Liu, M. L. Dustin, and A. Rao. 2005. A molecular dissection of lymphocyte unresponsiveness induced by sustained calcium signalling. Novartis Found. Symp. 267165-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanner, B. I., and H. Metzger. 1984. Initial characterization of the calcium channel activated by the cross-linking of the receptors for immunoglobulin E. J. Biol. Chem. 25910188-10193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macian, F., F. Garcia-Cozar, S. H. Im, H. F. Horton, M. C. Byrne, and A. Rao. 2002. Transcriptional mechanisms underlying lymphocyte tolerance. Cell 109719-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeyama, K., R. J. Hohman, H. Metzger, and M. A. Beaven. 1986. Quantitative relationships between aggregation of IgE receptors, generation of intracellular signals, and histamine secretion in rat basophilic leukemia (2H3) cells. Enhanced responses with heavy water. J. Biol. Chem. 2612583-2592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishibori, T., H. Xiong, I. Kawamura, M. Arakawa, and M. Mitsuyama. 1996. Induction of cytokine gene expression by listeriolysin O and roles of macrophages and NK cells. Infect. Immun. 643188-3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nomura, T., I. Kawamura, K. Tsuchiya, C. Kohda, H. Baba, Y. Ito, T. Kimoto, I. Watanabe, and M. Mitsuyama. 2002. Essential role of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 for gamma interferon production induced by listeriolysin O in mouse spleen cells. Infect. Immun. 701049-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otero, A. C., and G. A. Dos Reis. 1994. Functional inactivation of primary T-cells stimulated in vitro in the presence of cyclosporine. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 16941-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiter, Y., A. Ciobotariu, J. Jones, B. P. Morgan, and Z. Fishelson. 1995. Complement membrane attack complex, perforin, and bacterial exotoxins induce in K562 cells calcium-dependent cross-protection from lysis. J. Immunol. 1552203-2210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Repp, H., Z. Pamukci, A. Koschinski, E. Domann, A. Darji, J. Birringer, D. Brockmeier, T. Chakraborty, and F. Dreyer. 2002. Listeriolysin of Listeria monocytogenes forms Ca2+-permeable pores leading to intracellular Ca2+ oscillations. Cell. Microbiol. 4483-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose, F., S.-A. Zeller, T. Chakraborty, E. Domann, T. Machleidt, M. Kronke, W. Seeger, F. Grimminger, and U. Sibelius. 2001. Human endothelial cell activation and mediator release in response to Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors. Infect. Immun. 69897-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaughnessy, L. M., A. D. Hoppe, K. A. Christensen, and J. A. Swanson. 2006. Membrane perforations inhibit lysosome fusion by altering pH and calcium in Listeria monocytogenes vacuoles. Cell. Microbiol. 8781-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundrud, M. S., V. J. Torres, D. Unutmaz, and T. L. Cover. 2004. Inhibition of primary human T cell proliferation by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) is independent of VacA effects on IL-2 secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1017727-7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuchiya, K., I. Kawamura, A. Takahashi, T. Nomura, C. Kohda, and M. Mitsuyama. 2005. Listeriolysin O-induced membrane permeation mediates persistent interleukin-6 production in Caco-2 cells during Listeria monocytogenes infection in vitro. Infect. Immun. 733869-3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsukada, H., I. Kawamura, T. Fujimura, K. Igarashi, M. Arakawa, and M. Mitsuyama. 1992. Induction of macrophage interleukin-1 production by Listeria monocytogenes hemolysin. Cell. Immunol. 14021-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadsworth, S. J., and H. Goldfine. 1999. Listeria monocytogenes phospholipase C-dependent calcium signaling modulates bacterial entry into J774 macrophage-like cells. Infect. Immun. 671770-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wadsworth, S. J., and H. Goldfine. 2002. Mobilization of protein kinase C in macrophages induced by Listeria monocytogenes affects its internalization and escape from the phagosome. Infect. Immun. 704650-4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]