Abstract

A dose-response model using rhesus monkeys as a surrogate for pregnant women indicates that oral exposure to 107 CFU of Listeria monocytogenes results in about 50% stillbirths. Ten of 33 pregnant rhesus monkeys exposed orally to a single dose of 102 to 1010 CFU of L. monocytogenes had stillbirths. A log-logistic model predicts a dose affecting 50% of animals at 107 CFU, comparable to an estimated 106 CFU based on an outbreak among pregnant women but much less than the extrapolated estimate (1013 CFU) from the FDA-U.S. Department of Agriculture-CDC risk assessment using an exponential curve based on mouse data. Exposure and etiology of the disease are the same in humans and primates but not in mice. This information will aid in risk assessment, assist policy makers, and provide a model for mechanistic studies of L. monocytogenes-induced stillbirths.

Listeria monocytogenes is a food-borne pathogen responsible for the illness listeriosis, a disease especially severe for susceptible people, including fetuses and immunocompromised individuals. The infection resulting from L. monocytogenes exposure triggers a cell-mediated response, and fetuses, neonates, and individuals with suppressed immune systems such as AIDS patients, transplant recipients, and the elderly are unable to respond normally to this challenge. Among these at-risk populations, listeriosis is fatal to 20 to 40% of those who become infected, regardless of treatment (2, 7, 19). For all others not exquisitely sensitive to listeriosis, exposure to L. monocytogenes is seldom fatal. Several outbreaks of L. monocytogenes-associated febrile gastroenteritis have been reported among healthy adults, but only at doses of 105 CFU or greater (1, 4, 8, 17).

Concern about listeriosis led the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Food Safety Inspection Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to conduct a risk assessment for L. monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods (7). To conduct the risk assessment, mouse infection data were used to model the dose response but adjustments were made to the mouse data to more accurately predict the human dose response (7). In comparing the doses resulting in fatalities to 50% of the exposed individuals (LD50), the model based on mouse data underestimates sensitivity in humans based on the limited human data currently available. This discrepancy may result from mechanistic differences in how L. monocytogenes gains entry into epithelial cells in the intestine.

In vitro studies using human cell lines have shown that L. monocytogenes binds to the E-cadherin receptor, a transmembrane protein that assists in the formation of tight junctions between epithelial cells (16). The E-cadherin molecule in mice and rats has a glutamic acid at position 16, whereas human E-cadherin has a proline (12). Reduced susceptibility of mice and rats to oral infection with L. monocytogenes (13) may result from this change in the amino acid sequence, and mice transformed to express human E-cadherin in intestinal cells provide further evidence of the importance of proline at position 16. However, in vivo confirmation has yet to be done and other surface proteins may play a role in L. monocytogenes invasion of epithelial cells. No information has been published on the sequence of the E-cadherin molecule in rhesus monkeys.

A dose-response model that more accurately predicts human outcomes was identified as a data gap in the FDA-USDA-CDC risk assessment (7). The estimated lethal dose to 50% of the known exposures in susceptible human populations is markedly lower than that predicted for the general population, suggesting the need for an appropriate animal model for susceptible human populations, including pregnant women. In 2003, we published a study showing that listeriosis in pregnant rhesus monkeys closely resembles listeriosis during pregnancy in humans (20). The objectives of the present study were to use the pregnant rhesus monkey to obtain dose-response data and to develop a dose-response model for use in L. monocytogenes risk assessment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

L. monocytogenes inoculum preparation.

Monkey clinical strain 12443 was selected as the treatment strain because preliminary findings indicated that monkeys were at least as sensitive to this strain as to the other human or food isolate strains tested (20). Monkey clinical strain 12443 (serotype 1/2a) was originally isolated from a spontaneously occurring stillbirth in the outdoor-housed Yerkes National Primate Research Center rhesus monkey colony. Cultures were maintained on cryobeads at −80°C. At the time of use, beads were placed in 10 ml brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). Inoculum preparation was previously described in detail (20). Briefly, cultures were activated by two successive transfers in BHI broth at 37°C for 24 h, harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 3,500 × g, washed three times, and resuspended in sterile serological saline. Target doses of L. monocytogenes were estimated by determining the optical density of the culture in a saline solution and subsequently diluting it to the desired concentration. Inoculum preparation was previously described in detail (20). Briefly, 1 ml of the appropriate dose of L. monocytogenes was added to 9 ml of commercially available whipping cream that had been sterilized by autoclaving at 121°C for 15 min. Whipping cream was selected as the vehicle based on results from our previous study (20) that also examined two lower-fat vehicles ([i] half and half and [ii] skim milk). When administered in whipping cream, L. monocytogenes was as virulent as in the lower-fat vehicles. To confirm the number of L. monocytogenes CFU administered to the animals, the cultures were serially diluted in saline, surface plated onto BHI agar (Difco) in duplicate, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C before enumeration.

Isolation and confirmation of L. monocytogenes from tissue samples and fecal material.

Fetal tissue from stillbirths was confirmed positive both qualitatively and quantitatively for L. monocytogenes by the method of Cook (3), which was further described by Smith et al. (20). Briefly, for isolates identified as positive, two enrichments were done in nonselective and selective media, followed by selective plating on modified Oxford agar plates (Difco) for the qualitative method. For quantitation, samples were directly plated on modified Oxford agar plates. For both methods, colonies were examined for typical Listeria appearance by Henry illumination. Selected colonies (5 to 10%) were confirmed as L. monocytogenes by Gram stain and API Listeria tests (BioMérieux Industry, Hazelwood, MO).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns on selected samples were compared with the original L. monocytogenes strain to verify that they were the same. PFGE was performed according to the methods described by Graves and Swaminathan (9).

Animals.

Thirty-three pregnant rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were identified at 30 gestation days (gd) from the Yerkes National Primate Research Center's timed-breeding colony and placed into our study. Treatment and results for 10 of these animals were published previously in our report describing the pregnant rhesus monkey as a model for human listeriosis (20). The purpose of the preliminary study was to determine the optimal treatment regimen for the remaining 23 animals. Details of the selection of the treatment strain of L. monocytogenes and vehicle were previously described (20). Briefly, pregnancy was allowed to proceed normally until approximately the last third of pregnancy (∼110 gd), when animals were treated with L. monocytogenes. The time of treatment was chosen to correspond to approximately the last one-third of pregnancy, the time when most human cases are reported. For treatment, animals were sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg body weight) and L. monocytogenes was administered by nasogastric intubation. Animals were monitored daily for changes in eating behavior or activity or signs of illness such as diarrhea. However, no visible changes were noted in these indicators for any animal. In pregnancies resulting in stillbirths, vaginal bleeding often preceded the delivery of stillbirth and these animals were monitored closely. In some cases, stillbirths were delivered by caesarean section to preserve the health of the mother. No spontaneously occurring Listeria-induced stillbirth has ever been identified from the indoor-housed breeding colony at Yerkes. Table 1 lists the confirmed treatment dose, gd of treatment, and outcome for individual animals.

TABLE 1.

Summary of outcomes and conditions for administration of L. monocytogenes to pregnant monkeys

| Animal no. | Day of treatment (gd) | Confirmed dose (CFU)a | Birth outcome | Day of delivery (gd) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RVs3b | 109 | 2.4 × 107 | Stillborn | 162 |

| RFm2 | 103 | 3.5 × 106 | Stillborn | 136 |

| RKq4c | 108 | 1.7 × 106 | Normal | 169 |

| RDq4c | 110 | 1.5 × 106 | Normal | 176 |

| RPd5c | 109 | 1.3 × 106 | Normal | 171 |

| RLf5 | 111 | 6.1 × 105 | Stillborn | 175 |

| RKg1c | 111 | 3.8 × 105 | Normal | 173 |

| RPl4 | 117 | 1.2 × 105 | Normal | 170 |

| RGj3b,c | 112 | 8.6 × 104 | Stillborn | 173 |

| RFl5 | 109 | 7.2 × 104 | Normal | 176 |

| RKg1c | 111 | 7.1 × 104 | Normal | 169 |

| RKz4 | 111 | 4.6 × 104 | Normal | 171 |

| RIr2 | 111 | 2.9 × 104 | Normal | 170 |

| RTk3 | 113 | 6.3 × 103 | Normal | 171 |

| RFa5 | 105 | 3.8 × 103 | Normal | 172 |

| RDq4c | 110 | 2.1 × 103 | Normal | 175 |

| RLb6 | 109 | 2.1 × 103 | Normal | 169 |

| RWs4d | 120 | 1.9 × 103 | Stillborn | 138 |

| RPd5c | 110 | 1.6 × 103 | Normal | 173 |

| RMg3b | 110 | 1.2 × 103 | Stillborn | 163 |

| RIq1 | 106 | 7.1 × 102 | Normal | 170 |

| RRi3 | 112 | 6.0 × 102 | Normal | 175 |

| ROf3 | 112 | 3.0 × 102 | Normal | 174 |

L. monocytogenes was administered in whipping cream, and L. monocytogenes strain 12443 serotype 1/2a (a monkey clinical isolate) was used unless otherwise noted.

Animal had a stillbirth, but L. monocytogenes was not isolated from the fetus.

This animal had two pregnancies during the entire study period (including the study reported in reference 20); the pregnancies were at least 1 to 3 years apart.

Animal vomited immediately after treatment and was treated a second time with the same dose 3 days after the first treatment.

All animal work was done in full compliance with all federal regulations, including the Animal Welfare Act, and the Yerkes Center is fully accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee.

Sample collection.

Blood samples were collected before treatment, at either 4 days or 2 weeks posttreatment, at the time of delivery, and at 1 month postdelivery. Routine hematology was done on all blood samples, including white blood cell counts, number of platelets, mean corpuscular volume, hemoglobin, and numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils.

Fecal shedding of L. monocytogenes was determined by collecting fecal samples daily for 1 week, every other day for the second week, and once per week for 2 additional weeks. After collection, fecal samples were either cultured or refrigerated for not more than 48 h until enumeration.

Tissue samples were collected from placentas and aborted fetuses when possible. The strain of L. monocytogenes isolated from the tissue was confirmed as the treatment strain by PFGE.

Dose-response model.

The data were fitted to a log-logistic dose-response model by using the following formula: y = β/{[1 + (1 − p)/p] }, where β is the asymptotic value of probability of infection as the log dose approaches ∞ (β = 1 in this study), χ is the predicted lethal dose at a specified value of p = Pr (Pr is the probability of infection), and α is a rate parameter affecting the rate of increase of infection as the log dose increases. Nonlinear solution of the least-squares equations provided estimates of the parameters in the log-logistic model. The estimates of the parameters were obtained by solving the model for the observational data in Table 2 by the nonlinear statistical procedure (NLIN) in the SAS system (Statistical Analysis Software, version 6.12, 1996). A commonly used measure of the goodness of fit for nonlinear models is R2, which is defined as 1.0 minus the ratio of the residual sum of squares to the corrected total sum of squares. Although this ratio underestimates the degree of fit for nonlinear models containing asymptotic parameters such as the log-logistic model, it does provide for an overall general fit.

}, where β is the asymptotic value of probability of infection as the log dose approaches ∞ (β = 1 in this study), χ is the predicted lethal dose at a specified value of p = Pr (Pr is the probability of infection), and α is a rate parameter affecting the rate of increase of infection as the log dose increases. Nonlinear solution of the least-squares equations provided estimates of the parameters in the log-logistic model. The estimates of the parameters were obtained by solving the model for the observational data in Table 2 by the nonlinear statistical procedure (NLIN) in the SAS system (Statistical Analysis Software, version 6.12, 1996). A commonly used measure of the goodness of fit for nonlinear models is R2, which is defined as 1.0 minus the ratio of the residual sum of squares to the corrected total sum of squares. Although this ratio underestimates the degree of fit for nonlinear models containing asymptotic parameters such as the log-logistic model, it does provide for an overall general fit.

TABLE 2.

Summary of pregnancy outcomes after maternal treatment with L. monocytogenes

| Dose of L. monocytogenes (log10 CFU) | No. of stillbirths | No. of normal births | Avg gd of delivery

|

L. monocytogenes recovery from stillbirths | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stillbirths (n = 10) | Normal births (n = 23) | ||||

| 2.5 | 0 | 1 | —a | 174 | —a |

| 3.2 | 2 | 6 | 151 | 172 | Yes (1)b |

| 4.3 | 0 | 3 | — | 171 | — |

| 5.1 | 1 | 4 | 173 | 172 | No |

| 6.2 | 2 | 4 | 156 | 172 | Yes (1) |

| 7.1 | 2 | 3 | 152 | 170 | Yes (1) |

| 8.1 | 2 | 2 | 143 | 157 | Yes (2) |

| 10.6 | 1 | 0 | 167 | — | Yes (1) |

| All | 10 | 23 | 155 ± 15c,d | 170 ± 6e | Yes (6) |

No outcomes in this treatment group.

The value in parentheses is the number of stillbirths from which L. monocytogenes was isolated.

Average gd of delivery of 10 stillbirths.

Significantly different from gd of normal births (P < 0.05).

Average gd of delivery of 23 normal births.

RESULTS

Complete dosing and exposure information for each animal in this analysis is included in Table 1 or in reference 20. Although target doses of L. monocytogenes were used for treating animals, doses of L. monocytogenes were based on confirmatory cultures done at the time of treatment. For grouping, the doses were rounded to the nearest log dose and a geometric mean was calculated for each dose group (Table 2). This experiment was designed to include more animals in the lower-dose groups (20) because data are more difficult to obtain from those groups because of statistical limits in detecting effects to lower percentages of the population.

Of 33 pregnant rhesus monkeys treated with L. monocytogenes at various doses, 10 animals had pregnancies resulting in stillbirths, 1 animal had a premature birth with no obvious signs of listeriosis, and 22 animals had normal pregnancy outcomes (Tables 1 and 3; Table 2 in reference 20). Because the premature birth could not be confirmed as Listeria related, the data from that animal were included in the “normal birth” group. Animals whose pregnancies ended with stillbirth delivered those fetuses at a significantly earlier time (155 ± 15 gd) compared to normal births (170 ± 6 gd) (P < 0.05), although both groups had a wide range in the time to delivery, with stillbirths ranging from 136 to 175 gd and normal births ranging from 147 to 176 gd (Table 1; see Table 2 in reference 20).

TABLE 3.

Isolation of L. monocytogenes from maternal fecal samples after oral challenge

| Dose of L. monocytogenes (log10 CFU) | Fecal samples positive for L. monocytogenes (%)a

|

Peak L. monocytogenes shedding in feces (CFU)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stillbirths | Normal births | Stillbirths | Normal births | |

| 2.5 | NAb | 0/8 (0); 1c | NA | —d |

| 3.2 | 5/13 (39); 2c | 0/11 (0); 6 | 1.5 × 107 | — |

| 4.3 | NA | 0/13 (0); 3 | NA | — |

| 5.1 | 0/14 (0); 1 | 0/15 (0); 4 | — | — |

| 6.2 | 1/13 (8); 2 | 1/14 (7); 4 | 6.6 × 105 | 4.3 × 103 |

| 7.1 | 4/14 (29); 2 | 2/12 (17); 3 | 1.3 × 107 | 5.2 × 105 |

| 8.1 | 7/14 (50); 2 | 3/11 (27); 2 | 1.7 × 107 | 8.0 × 106 |

| 10.6 | 4/11 (36); 1 | NA | 9.4 × 105 | NA |

Average number of days L. monocytogenes isolated from fecal samples/average number of days collected.

NA, no animals in group.

Number of animals from which samples were collected.

—, all fecal samples collected were negative for L. monocytogenes.

Fecal samples were collected to determine whether L. monocytogenes had colonized the intestinal tract and, if so, how long the animals shed L. monocytogenes after oral exposure. Animals with normal births had detectable levels of L. monocytogenes in their feces only if exposed to 106 or more CFU of L. monocytogenes, but animals with stillbirths had detectable levels of L. monocytogenes after receiving doses of 103 CFU or greater (Table 3). Animals with stillbirths shed L. monocytogenes for significantly longer periods of time than animals with normal births (P < 0.05), regardless of the dose (Table 3). This suggests that, for any given dose, the longer L. monocytogenes is shed in the feces, the greater is the risk of stillbirth. Additionally, fecal samples from mothers were confirmed L. monocytogenes positive at each dose level that resulted in stillbirth (Table 3).

Routine hematology was done on all blood samples, including white blood cell counts, number of platelets, mean corpuscular volume, hemoglobin, and numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils, and all of these parameters were within the normal range for rhesus monkeys. In animals that gave birth naturally, red blood cell counts were below the normal range for rhesus monkeys, but this was attributed to the loss of blood while giving birth (data not shown).

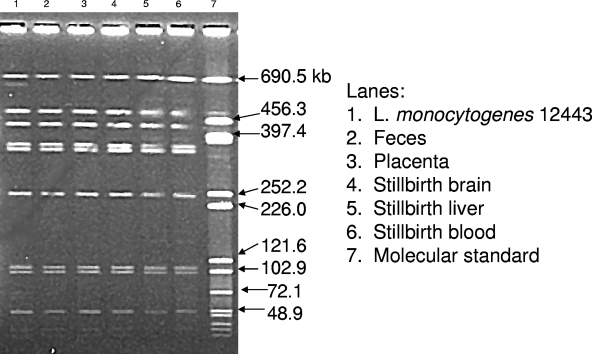

To confirm that L. monocytogenes had infected the fetus and was likely the cause of the stillbirth, fetal tissue was collected when possible and L. monocytogenes was isolated. In each case where a stillbirth was confirmed positive for L. monocytogenes, the fecal samples collected from the mother were also positive. Sixty percent of stillbirths in animals exposed at 103 to 1010 CFU were confirmed positive for L. monocytogenes (Table 2). In cases where L. monocytogenes was isolated from fetal tissue, the same treatment strain was also isolated from the placenta and feces from the mother and selected samples were confirmed by PFGE (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PFGE of the treatment strain of L. monocytogenes and strains isolated from maternal feces and maternal and fetal tissues isolated from an animal whose pregnancy resulted in a stillbirth. The identical PFGE pattern of lanes 2 to 6 compared to lane 1 verifies that the strains isolated from the maternal and fetal tissues were the same as the treatment strain. Lanes: 1, L. monocytogenes 12443; 2, feces; 3, placenta; 4, stillbirth brain; 5, stillbirth liver; 6, stillbirth blood; 7, molecular size standard.

The form of the log-logistic model used for describing the dose-response relationship in this study is shown above. Determination of LDs is based on the values of p. For example, if p = 0.10 or 0.50, then the values of χ are the LD10 or LD50, respectively. When p = 0.50, the term (1 − p)/p drops out of the model completely.

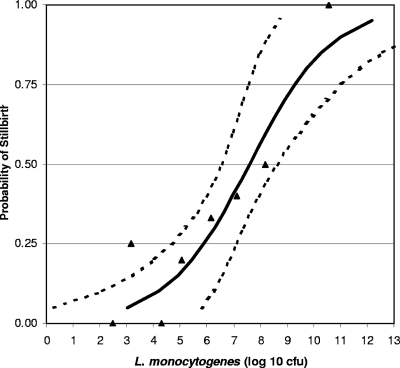

Estimates of the parameters α and χ are −6.446 × 10−1 and 8.45 × 107, respectively. Since we used a value of p = 0.50, the estimate of χ is the LD50 with confidence intervals (LD50lower = 3.63 × 106, LD50upper = 4.27 × 108). The estimate of α determines the rate at which infection is achieved. The estimated dose-response curve comparing the estimated responses with the observed responses is presented in Fig. 2, with an overall general fit of R2 = 0.88, where R2 is defined as [(1 − residual sum of squares)/corrected sum of squares] × 100.

FIG. 2.

Probability of stillbirths after pregnant rhesus monkeys were orally exposed to L. monocytogenes during the third trimester. The dose-response relationship was derived by using a log-logistic model. The solid line represents the log-logistic fit to the observed data; the dotted lines represent the 95% upper and lower confidence limits.

DISCUSSION

To maximize the data set for analyses and for dose-response modeling, data from the present study were combined with data from our previous study (20), which included five strains of L. monocytogenes and three different vehicles. Support for this approach has been demonstrated by using mice. Combining five strains of L. monocytogenes into a cocktail does not significantly affect infection in A/J mice compared to giving the strain individually (5). Similarly, administering a single strain of L. monocytogenes in food matrices with various degrees of fat does not significantly affect fecal shedding or invasion of the liver and spleen in mice (18). More importantly, combining these different exposure scenarios more closely reflects the human situation, which includes exposure to different strains of L. monocytogenes found in many different food matrices, and may alleviate the need for some of the uncertainty factors used in risk assessment.

Several endpoints were monitored as indicators of L. monocytogenes infection, including the number of days L. monocytogenes was shed in the feces and the peak number of CFU of L. monocytogenes shed in the feces. These indicators, along with the number of days to delivery, are correlated with increasing doses, regardless of the birth outcome (Table 3). The longer an animal shed L. monocytogenes in her feces, the more likely she was to have a stillbirth. It is possible that fecal shedding of L. monocytogenes could be used as a predictor of stillbirths, although it is not conclusive evidence of impending stillbirth. Some pregnant animals were able to withstand exposure to 108 CFU, and shed L. monocytogenes in their feces, without adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Dose-response model.

A diverse group of models varying in complexity have been explored for modeling the relationship between exposure to pathogenic bacteria and adverse outcomes (10, 11, 14), and eight models were reviewed in FDA-USDA-CDC (7) and FAO-WHO (6) risk assessments. Arguments have been made alternately for choosing models that are reflective of underlying mechanisms (6, 7) or for use of the simplest model that provides an acceptable fit (6, 7). Frequently, the available data are not sufficient to permit critical comparisons among closely related models. After examining several dose-response models (including exponential, logistic, Weibull gamma, and probit) and our previous experience with dose-response models for pathogens (11, 21), we found them to predict similar effects near the LD50 region for the dose-response curve. At low doses, at which effects occur in ≤1% of the population, the different models diverge but collected data sets are generally not sufficient to justify selection from among models. We chose the log-logistic model from among those models we explored on the basis of its fit of the data in the midrange of the dose-response curve, its extensive use for growth response modeling as reported in the literature, and its simplicity in relating biological interpretations of the parameters. In general, the more complex models did not provide a significant improvement in fit, but where they did, it was due to the increase in the number of parameters in the models.

Dose response of L. monocytogenes in humans and rhesus monkeys.

The largest reported outbreak of listeriosis among pregnant women occurred in Los Angeles County, CA, in 1985 (15), when consumption of L. monocytogenes-contaminated cheese was associated with 93 pregnancy-related cases and 30 deaths among fetuses and neonates. The FAO-WHO risk assessment for L. monocytogenes (6) has estimated the 50% perinatal morbidity for the outbreak at 1.9 × 106 CFU. The estimated morbidity for this outbreak compares favorably with the LD50 calculated from the monkey dose-response curve, approximately 107 CFU. This is in contrast to the perinatal (including fetal) LD50 in the range of 1013 to 1014 CFU based on the exponential dose-response graph (Fig. IV-7) published in the FDA-USDA-CDC L. monocytogenes risk assessment (7). This discrepancy occurs in part because the shape of the dose-response curve was based on data from a mouse study and adjustment factors were applied to the curve so that it reflects the estimated number of human listeriosis cases in the United States (7). In addition, the LD50 estimated in the FDA-USDA-CDC (7) and FAO-WHO (6) L. monocytogenes risk assessments incorporates variation in the virulence of L. monocytogenes strains that may account for some of the discrepancy. Strain variation is not incorporated into the rhesus model or into estimates based on outbreaks.

When the morbidity from the Los Angeles outbreak (15) calculated by the FAO-WHO (6) is plotted on the dose-response graph based on the monkey data, the morbidity for humans (106 CFU of L. monocytogenes) falls within the 95% confidence limit of the curve (Fig. 2). These LD50s are also similar to that calculated for guinea pigs at 107 CFU (21). The similarity among the FAO-WHO 50% perinatal morbidity (6) based on the Los Angeles outbreak, the LD50 for guinea pigs (21), and the LD50 based on the monkey data suggests that the use of models representing at-risk populations which do not require adjustments is possible and may facilitate risk assessment.

Conclusions.

Pregnant rhesus monkeys exposed to L. monocytogenes through the gastrointestinal tract during the last trimester of pregnancy are susceptible to having stillbirths with the same etiology as humans. Likewise, the LD50 calculated from the rhesus dose-response curve is 107 CFU, which compares favorably to the estimated 50% human morbidity calculated from outbreak data by the FAO-WHO of 106 CFU (6). To estimate the percentage of a population affected at the 10% level or lower is greatly affected by which dose-response model is used, but the choice of model does not have much impact on the 50% level. This suggests that when comparing dose-response information, the midrange of the dose-response curve is likely to be more accurate than the extremes of the curve. Using dose-response data obtained with rhesus monkeys offers advantages over rodent models because monkeys can be exposed orally, the same as humans, and all evidence to date suggests that the results of infection are the same as in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by FDA grant FU-U-001622-03 and Yerkes Center base grant RR0016 from the NIH. We gratefully acknowledge the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Listeria Reference Laboratory for providing human clinical strains of Listeria.

We acknowledge the excellent technical help of Sonya Lambert and Jun Sup Lee, University of Georgia, and Stephanie Ehnert at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

Editor: J. F. Urban, Jr.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 December 2007.

Dedicated to our friend and colleague Harold M. McClure, 1937-2004.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aureli, P., G. C. Fiorucci, D. Caroli, G. Marchiaro, O. Novara, L. Leone, and S. Salmaso. 2000. An outbreak of febrile gastroenteritis associated with corn contaminated by Listeria monocytogenes. N. Engl. J. Med. 3421236-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1992. Update: foodborne listeriosis—United States, 1988-1990. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 41251, 257-258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook, L. V. 1998. Isolation and identification of Listeria monocytogenes from red meat, poultry, egg and environmental samples, sect. 8.1-8.9. In B. P. Dey and C. P. Lattuada (ed.), USDA/FSIS microbiology laboratory guide book. Food Safety and Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC.

- 4.Dalton, C. B., C. C. Austin, J. Sobel, P. S. Hayes, W. F. Bibb, L. M. Graves, B. Swaminathan, M. E. Proctor, and P. M. Griffin. 1997. An outbreak of gastroenteritis and fever due to Listeria monocytogenes in milk. N. Engl. J. Med. 336100-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faith, N. G., L. D. Peterson, J. B. Luchansky, and C. J. Czuprynski. 2006. Intragastric inoculation with a cocktail of Listeria monocytogenes strains does not potentiate the severity of infection in A/J mice compared to inoculation with the individual strains comprising the cocktail. J. Food Prot. 692664-2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations and World Health Organization. 2004. Risk assessment of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods. Interpretative summary. Microbial risk assessment series, no. 4. http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/micro/en/mra4.pdf.

- 7.Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Quantitative assessment of relative risk to public health from foodborne Listeria monocytogenes among selected categories of ready-to-eat foods. http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/∼frf/forum04/www.foodsafety.gov/∼dms/lmr2-toc.html.

- 8.Frye, D. M., R. Zweig, J. Sturgeon, M. Tormey, M. LeCavalier, I. Lee, L. Lawani, and L. Mascola. 2002. An outbreak of febrile gastroenteritis associated with delicatessen meat contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35943-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graves, L. M., and B. Swaminathan. 2001. PulseNet standardized protocol for subtyping Listeria monocytogenes by macrorestriction and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 6555-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas, C. N., J. B. Rose, and C. P. Gerba (ed.). 1999. Quantitative microbial risk assessment, p. 260-319. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 11.Holcomb, D. L., M. A. Smith, G. O. Ware, Y. Hung, R. E. Brackett, and M. P. Doyle. 1999. Comparison of six dose response models for use with food borne pathogens. Risk Anal. 191091-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lecuit, M., S. Dramsi, C. Gottardi, M. Fedor-Chaiken, B. Gumbiner, and P. Cossart. 1999. A single amino acid in E-cadherin responsible for host specificity toward the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO J. 183956-3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lecuit, M., S. Vandormael-Pournin, J. Lefort, M. Huerre, P. Gounon, C. Dupuy, C. Babinet, and P. Cossart. 2001. A transgenic model for listeriosis: role of internalin in crossing the intestinal barrier. Science 2921722-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindqvist, R., and A. Westoo. 2000. Quantitative risk assessment for Listeria monocytogenes in smoked or gravid salmon and rainbow trout in Sweden. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 58181-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linnan, M. J., L. Mascola, X. D. Lou, V. Goulet, S. May, C. Salminen, D. W. Hird, M. L. Yonekura, P. Hayes, R. Weaver, A. Audurier, B. D. Plikaytis, S. L. Fannin, A. Kleks, and C. V. Broome. 1988. Epidemic listeriosis associated with Mexican-style cheese. N. Engl. J. Med. 319823-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mengaud, J., H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, R. M. Mege, and P. Cossart. 1996. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell 84923-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miettinen, M. K., A. Siitonen, P. Heiskanen, H. Haajanen, K. J. Bjorkroth, and H. J. Korkeala. 1999. Molecular epidemiology of an outbreak of febrile gastroenteritis caused by Listeria monocytogenes in cold-smoked rainbow trout. J. Clin. Microbiol. 372358-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mytle, N., G. L. Anderson, S. Lambert, M. P. Doyle, and M. A. Smith. 2006. Effect of fat content on infection by Listeria monocytogenes in a mouse model. J. Food Prot. 69660-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuchat, A., K. A. Deaver, J. D. Wenger, B. D. Plikaytis, L. Mascola, R. W. Pinner, A. L. Reingold, and C. V. Broome. 1992. Role of foods in sporadic listeriosis. I. Case-control study of dietary risk factors. JAMA 2672046-2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith, M. A., K. Takeuchi, R. E. Brackett, H. M. McClure, R. B. Raybourne, K. M. Williams, U. S. Babu, G. O. Ware, J. R. Broderson, and M. P. Doyle. 2003. Nonhuman primate model for Listeria monocytogenes-induced stillbirths. Infect. Immun. 711574-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams, D., E. A. Irvin, R. A. Chmielewski, J. F. Frank, and M. A. Smith. 2007. Dose-response of Listeria monocytogenes after oral exposure in pregnant guinea pigs. J. Food Prot. 701122-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]