Abstract

The opportunistic human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus causes severe systemic infections and is a major cause of fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. A. fumigatus conidia activate the alternative pathway of the complement system. In order to assess the mechanisms by which A. fumigatus evades the activated complement system, we analyzed the binding of host complement regulators to A. fumigatus. The binding of factor H and factor H-like protein 1 (FHL-1) from human sera to A. fumigatus conidia was shown by adsorption assays and immunostaining. In addition, factor H-related protein 1 (FHR-1) bound to conidia. Adsorption assays with recombinant factor H mutants were used to localize the binding domains. One binding region was identified within N-terminal short consensus repeats (SCRs) 1 to 7 and a second one within C-terminal SCR 20. Plasminogen was identified as the fourth host regulatory molecule that binds to A. fumigatus conidia. In contrast to conidia, other developmental stages of A. fumigatus, like swollen conidia or hyphae, did not bind to factor H, FHR-1, FHL-1, and plasminogen, thus indicating the developmentally regulated expression of A. fumigatus surface ligands. Both factor H and plasminogen maintained regulating activity when they were bound to the conidial surface. Bound factor H acted as a cofactor to the factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b. Plasminogen showed proteolytic activity when activated to plasmin by urokinase-type plasminogen activator. These data show that A. fumigatus conidia bind to complement regulators, and these bound host regulators may contribute to evasion of a host complement attack.

Aspergillus fumigatus is the most important airborne fungal pathogen. The frequency of invasive mycoses due to this opportunistic fungal pathogen has increased significantly during the last two decades (reviewed in references 4 and 37).

In healthy individuals, A. fumigatus can infect the lung, but the establishment of disease is prevented by the host immune system. The innate immune system represents the first line of defense against conidia. Inhaled conidia are immediately confronted with the host complement system and phagocytic cells. The adaptive immune system displays its protective role at the onset of an infection. The complement system is activated on the conidial surface (21) and results in the cleavage of C3. The cleavage products of this central component of the complement cascade act as opsonins on the surfaces of pathogens and enhance phagocytosis by neutrophils, macrophages, and eosinophils (46). Opsonization with complement proteins was shown to be of importance for the phagocytosis of A. fumigatus conidia, the key process in the defense against this pathogen (44).

Activation of the complement system occurs via three pathways: the alternative, the lectin, and the classical. The alternative pathway (AP) is activated on the surfaces of pathogens and plays a pivotal role in the clearance of microorganisms (51). Further activation of the terminal pathway leads to the formation of cytolytic membrane attack complexes on the target surfaces. These attack complexes are important for the clearance of some bacterial pathogens but appear to have a minor role in the defense against fungi, most possibly due to their thick cell walls. The complement activation system is controlled by fluid-phase and cell surface-bound regulators. The central fluid-phase regulators of the AP are factor H and factor H-like protein 1 (FHL-1). The latter is encoded by an alternatively processed nuclear RNA transcript derived from the factor H gene (10, 50). Factor H has a molecular mass of 150 kDa and consists of 20 homologous short consensus repeat domains (SCRs), and FHL-1, which has a molecular mass of 42 kDa, is composed of 7 SCRs which are identical to the N-terminal SCRs of factor H. In addition, FHL-1 has a unique C-terminal extension of four amino acids. Both factor H and FHL-1 act as cofactors for the plasma serine protease factor I. Thus, they mediate the cleavage of C3b (24, 32, 36) and accelerate the decay of the C3 convertase C3bBb (26, 49). Factor H and FHL-1 compete with factor B in binding to intact C3b (9). These regulatory functions lead to the downregulation or termination of the complement cascade. The factor H family also comprises factor H-related protein 1 (FHR-1) and five other FHRs, which display high identity to factor H, though, to date, no complement regulatory activity has been assigned. FHR-1 consists of five SCRs and has two plasma forms with either one (37-kDa) or two (43-kDa) carbohydrate side chains attached.

Several pathogenic microbes bind host complement regulators to their surfaces and thus mediate immune evasion and the downregulation of complement activation (for a review, see reference 51). Candida albicans (30, 31), Streptococcus pyogenes (16, 19, 20, 48), Streptococcus pneumoniae (11, 33), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (39), Neisseria meningitidis (38), Borrelia burgdorferi (1, 12, 23), Borrelia hermsii (17, 41), Echinococcus granulosus (8), Treponema denticola (29), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (27), human immunodeficiency virus (43), and West Nile virus (6) all bind to factor H and/or FHL-1. FHR-1 binds to the surface of B. burgdorferi and P. aeruginosa, and the corresponding binding proteins were identified as BbCRASP-3 to -5 (12) and as Tuf (27). Plasminogen is bound by various human pathogens, including C. albicans (7) and B. hermsii (41, 51).

In their bound configuration, these regulators maintain either proteolytic activity or complement regulatory activities and thus protect microbes against complement-mediated phagocytosis and direct lysis (7).

Since A. fumigatus is exposed to the host complement system during infection, we studied how this pathogen evades the destructive effects of the activated system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. fumigatus strains and growth conditions.

A. fumigatus strain ATCC 46645 was cultivated on Aspergillus minimal medium agar plates at 37°C for 4 days. Conidia were harvested in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; without MgCl2) with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20. For liquid culture, 50 ml of Aspergillus minimal medium was inoculated with conidium concentrations ranging from 2 × 108 to obtain young hyphae (6-h incubation) to 2 × 109 to obtain swollen spores (3-h incubation).

Sera, antibodies, and proteins.

Pooled normal human sera (NHS) were obtained from healthy human donors and stored at −20°C until used. EDTA was added to the sera at a concentration of 10 mM (NHS-EDTA).

The antibodies used in the experiments were mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) N22 for the detection of the N-terminal SCRs of factor H and FHL-1 and MAbs C18 and M16 for the detection of C-terminal SCR 20 of factor H (34). Polyclonal goat anti-factor H antiserum, polyclonal goat antiplasminogen antiserum, and polyclonal goat anti-C3 antiserum were obtained from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse antiserum was obtained from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-goat antiserum and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse antiserum were obtained from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark).

Factor H, factor I, and C3b were purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany).

Serum absorption experiments.

A. fumigatus conidia (2 × 109), swollen spores, or young hyphae were resuspended either in 150 μl NHS-EDTA for NHS absorbance or in binding buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 [pH 7.4]) for incubation with concentrated recombinant mutant proteins of factor H and FHL-1 (SCRs 1 to 4, 1 to 5, 1 to 6, 8 to 20, 8 to 11, 11 to 15, 15 to 19, 15 to 20, or 19 and 20) or with recombinant FHL-1. To confirm the specificity of the binding, incubation experiments were also performed with binding buffer containing 1× RotiBlock (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Conidia were incubated for 60 min at 37°C with vertical rotation (4 rpm). The conidia were washed five times with 1 ml of binding buffer. An additional wash was performed with 150 μl of binding buffer. This wash fraction was analyzed by Western blotting. Proteins bound to the surfaces of the cells were eluted with 150 μl of 3 M potassium thiocyanate, and the eluate fractions were collected.

Samples of the wash and eluate fractions were subjected to nonreducing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for the detection of factor H and FHL-1 and to reducing SDS-PAGE for the detection of C3b. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes via semidry blotting. The membranes were blocked with 2.5% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBS-0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20-1× RotiBlock (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and incubated further with the following antibodies (dilution, 1:1,000) for 120 min at RT: goat polyclonal anti-factor H antiserum for the detection of factor H, MAb B22 for the detection of FHL-1, and goat polyclonal antiplasminogen antiserum for the detection of plasminogen. After five washes with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20-PBS, HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-goat or anti-mouse antiserum was added at a dilution of 1:2,500, and the membranes were incubated at RT for 60 min. After five washes with 0.1% Tween 20-PBS, the proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany).

Immunofluorescence assays.

A. fumigatus conidia (5 × 107) were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with 10 μg purified factor H. After incubation, the conidia were washed three times with ice-cold PBS (0.15 M NaCl, 0.03 M phosphate [pH 7.2]), and nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 2% (wt/vol) BSA-PBS for 30 min at 37°C. The samples were incubated with M16 antiserum directed against the C-terminal part of factor H for 1 h at 37°C (dilution, 1:200). After three washes with PBS, the secondary Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G was added at a dilution of 1:400 in 2% (wt/vol) BSA-PBS and incubated for 1 h. The conidia were washed once with PBS, and 10 μg/ml calcofluor was added. After incubation for 30 min at RT, the conidia were washed three times with PBS, and samples were examined using the Zeiss LSM 5 Live confocal laser-scanning microscope. Data were processed with Zeiss LSM 5 Live software and Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

Expression of recombinant proteins.

Recombinant mutant proteins of factor H (SCRs 1 to 4, 1 to 5, 1 to 6, 8 to 20, 8 to 11, 11 to 15, 15 to 19, 15 to 20, and 19 and 20) and FHL-1 (SCRs 1 to 7) were produced in the baculovirus system as described previously (24, 25). Briefly, Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells were grown in expression medium (BioWhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with streptomycin (100 μg/ml), penicillin (100 U/ml), and amphotericin B (250 ng/ml) and infected with a recombinant baculovirus at a multiplicity of infection of 5. The culture supernatant was collected 9 days after infection, and recombinant proteins were purified by Ni+-chelate chromatography as described previously (25) or by Ákta fast protein liquid chromatography purification (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany). The proteins were concentrated using Centricon microconcentrators with a cutoff at 10 kDa (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

Effect of heparin on factor H binding to A. fumigatus.

The effect of heparin on the binding of factor H to A. fumigatus was assayed by incubating 5,000 IU/ml of heparin with factor H for 30 min. This mixture was added to conidia (2 × 109) and incubated for 60 min with vertical rotation at 4 rpm. The wash and elution procedures are described in “Serum absorption experiments” above. Heparin (5,000 IU/ml) was obtained from Sigma (Taufkirchen, Germany).

Quantitative analysis was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Factor H at a constant concentration (0.2 μg/ml) was incubated with different concentrations of heparin (0 to 640 IU/ml) for 30 min at RT. Incubation of the mixtures with conidia (5 × 106/well) was performed in 96-well MultiScreen-HTS-BV filtration plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Liquids were removed from the wells by vacuum. Conidia were incubated with factor H/heparin for 1 h with horizontal shaking at 400 rpm. After three wash steps with PBS, conidia were incubated with polyclonal goat anti-factor H antiserum (1:4,000 in 0.02% [wt/vol] BSA-PBS) and subsequently with HRP-coupled anti-goat antiserum (1:5,000 in 0.02% [wt/vol] BSA-PBS). HRP activity was measured by the addition of a BM Blue POD substrate (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Plasminogen activation.

Conidia (5 × 106 to 1 × 107/well) were incubated with plasminogen (1 μg/ml to 2 μg/ml) in 96-well MultiScreen-HTS-BV filtration plates for 1 h in PBS. After extensive washing, plasmin substrate S-2251 (0.3 mg/ml) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA; 0.16 μg/ml) were added. The reaction was performed with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 15 min. Samples were filtered in a microtiter plate, and absorption was measured at 402 nm against a reference wavelength of 690 nm.

Cofactor assay.

A cofactor activity assay of surface-attached regulators was performed as described previously (13). Conidia (2 × 109) were washed two times with binding buffer and incubated with NHS-EDTA or purified factor H (100 μg/ml) for 60 min at 37°C on a shaker. The conidia were washed five times with binding buffer and were resuspended in 150 μl of binding buffer. A total of 1.96 μg C3b and 960 ng factor I were added, and the cells were further incubated for 60 min at 37°C. The samples were centrifuged and the supernatants analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions to detect the cleavage of C3b. As a positive control, purified factor H (50 ng) was added to the reaction mixture. Gels were blotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and C3b cleavage products were detected with anti-C3 polyclonal goat antiserum. Detection was performed as described in “Serum absorption experiments” above.

RESULTS

Aspergillus fumigatus conidia bind factor H, FHL-1, and FHR-1 from human serum.

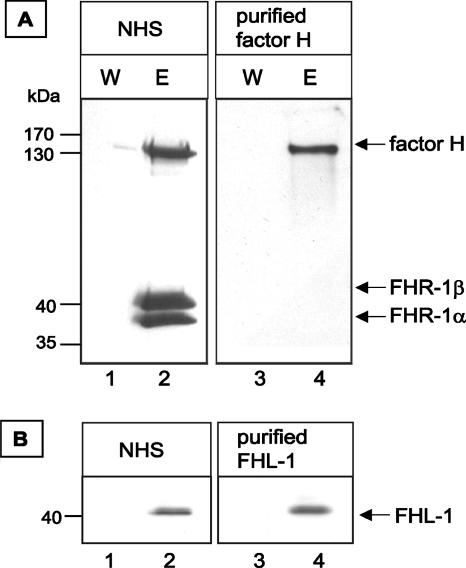

To determine whether A. fumigatus binds the human complement regulators factor H, FHR-1, and FHL-1, conidia of strain ATCC 46645 were incubated in NHS-EDTA. After extensive washing, the bound proteins were eluted. The wash and eluate fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. Factor H was detected in the eluate fractions as a 150-kDa protein by an anti-factor H antiserum (Fig. 1A). The FHR-1 protein was also detected by this antiserum as 37-kDa and 43-kDa FHR-1 isoforms (Fig. 1A). The presence of both factor H and FHR-1 in the eluate and not in the wash fractions demonstrates that A. fumigatus conidia were able to acquire the human complement regulators factor H and FHR-1 from NHS. In addition, the presence of FHL-1 in the eluate fraction was shown by using a specific MAb which detects 42-kDa FHL-1 but not FHR-1 (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Binding of factor H and FHL-1 to A. fumigatus conidia. Factor H, FHR-1, and FHL-1 were detected with polyclonal anti-factor H antiserum (for factor H and FHR-1) and mouse MAb directed against FHL-1. Conidia were incubated with either NHS or purified factor H and washed, and bound proteins were eluted with a chaotrope solution. Proteins in wash (W) and eluate (E) fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a membrane, and analyzed by Western blot analysis.

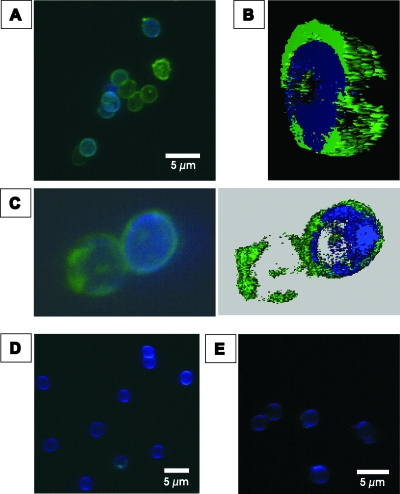

Immunofluorescence of the binding of factor H to conidia of A. fumigatus.

The binding of factor H to A. fumigatus conidia and the surface distribution of the bound immune regulator were analyzed by immunofluorescence. Conidia were incubated with purified factor H, and surface binding was visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. The specific fluorescence signal confirmed the binding of factor H to the surfaces of the conidia (Fig. 2A to C). A patchy distribution of factor H on the surfaces of the conidia was observed, suggesting clustering of the fungal ligand molecules. No fluorescence was detected on conidia with the secondary antibody alone or without the addition of factor H in the presence of both antibodies (Fig. 2D and E). Specific binding of factor H to conidia was confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Binding of factor H to A. fumigatus conidia. Conidia were incubated with purified factor H, and binding was visualized by immunofluorescence with mouse MAb directed against the C terminus of factor H and an Alexa 488-coupled secondary antibody (green). The cell wall was stained with calcofluor (blue). (A) Immunofluorescence of conidia. (B) Three-dimensional rendering of the fluorescence of the conidia in panel C. (C) Higher magnification of two conidia. Note the patchy surface distribution of the fluorescence. (D) Negative control without factor H. (E) Negative control without the first antibody.

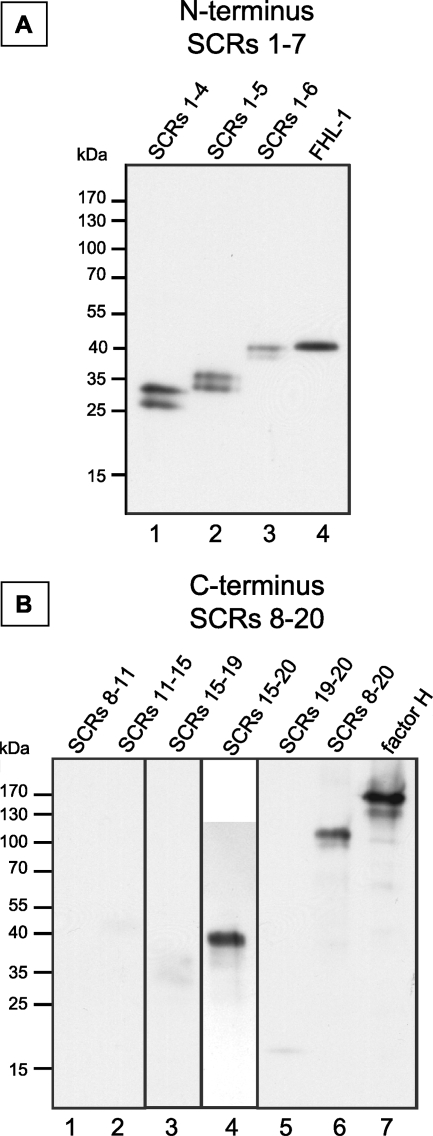

Localization of the binding sites within factor H and FHL-1.

To localize the binding domain(s) of factor H and FHL-1, conidia were incubated with recombinant mutants of the proteins encompassing SCRs 1 to 4, 1 to 5, 1 to 6, 1 to 7 (FHL-1), 8 to 11, 11 to 15, 15 to 19, 15 to 20, 19 and 20, and 8 to 20. After incubation, wash fractions (data not shown) and eluate fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. This approach identified two distinct binding regions. One region is located within the N terminus of factor H and FHL-1 in SCRs 1 to 7, as demonstrated by the binding of SCRs 1 to 4, 1 to 5, and 1 to 6 (Fig. 3A). A second binding site, unique to factor H, was localized to the C terminus. Recombinant mutant proteins representing SCRs 15 to 20, 19 and 20, and 8 to 20 (Fig. 3B) bound to A. fumigatus conidia, but mutant proteins representing SCRs 8 to 11, 11 to 15, and 15 to 19 did not (Fig. 3B). SCRs 19 and 20 bound with less intensity. The fainter band might be due to the instability of this small protein. Mutant proteins encompassing SCRs 1 to 4 and 1 to 5 were identified as doublet bands. Their identities were validated by mass spectrometry analysis (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Localization of the binding site of factor H. Conidia were incubated with purified factor H mutant proteins, and bound proteins were eluted with a chaotrope solution. After SDS-PAGE separation, Western blot analysis was performed with polyclonal factor H antiserum. Incubation experiments were performed in the presence and absence of blocking solutions and showed similar results. (A) Binding of mutant proteins consisting of N-terminal SCRs; (B) binding of mutant proteins consisting of internal and C-terminal SCRs.

In summary, factor H uses two binding regions for its attachment to A. fumigatus conidia, whereas FHL-1 uses one region. One binding region is located within SCRs 1 to 7 and is common to both factor H and FHL-1. The second region is located in the C-terminal region, in SCR 20, of factor H.

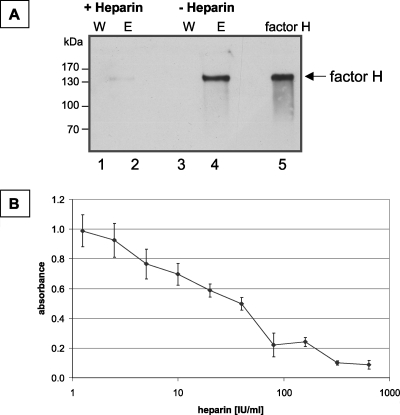

Heparin inhibits factor H binding to A. fumigatus conidia.

Factor H has four heparin interaction sites, which have been localized to SCR 7, SCR 9, SCR 13, and SCR 20 (35, 50). As some heparin binding domains of factor H mediate its attachment to microbial surfaces, we asked whether heparin affects the binding of factor H to A. fumigatus. At a concentration of 600 IU/experiment (4,000 IU/ml), heparin completely inhibited the attachment of factor H to conidia, as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A). Quantitative studies showed that the effect was dose dependent. At a concentration of 80 IU/ml, heparin inhibited the binding of factor H to conidia by ca. 50% (Fig. 4B). These results showed that the binding sites of factor H to A. fumigatus overlap or are even identical to the heparin binding sites. This effect is in agreement with the observation that one of the binding sites is located in SCR 20.

FIG. 4.

Heparin inhibits the binding of factor H to conidial surfaces. (A) A. fumigatus conidia (2 × 109) were incubated with purified factor H (10 μg) in the presence or absence of heparin (800 IU). Bound proteins were eluted with a chaotrope solution, and wash (W) and eluate (E) fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Fifty nanograms of purified factor H was used as a control. (B) Factor H was preincubated with increasing concentrations of heparin (0 to 640 IU/ml) and subsequently incubated with conidia (5 × 106) in microtiter plates with a filter bottom. The binding of factor H to conidia was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a polyclonal antiserum directed against factor H.

Binding of plasminogen to conidia of A. fumigatus.

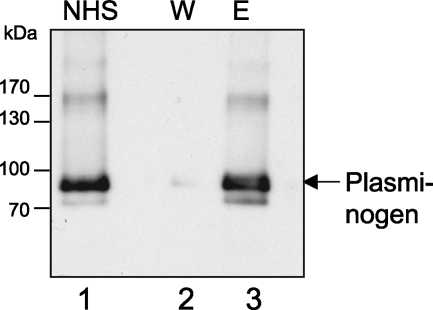

Plasminogen is a member of the soluble proteins of the blood. It was previously shown (41) that plasminogen, if activated to plasmin, can exhibit proteolytic activity when bound to the surfaces of pathogenic bacteria, such as B. hermsii (12) or P. aeruginosa (27). This proteolytic activity seems important for the degradation of the proteinaceous matrix, thereby allowing the bacteria to spread into the tissue. Therefore, we analyzed whether plasminogen can also bind to A. fumigatus. As shown here, plasminogen bound to A. fumigatus conidia. After the incubation of conidia with NHS, plasminogen was detected in the eluate fractions as an ∼90-kDa protein by Western blot analysis using a polyclonal antiplasminogen goat antiserum (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Binding of plasminogen to A. fumigatus conidia. Conidia were incubated with NHS and washed, and bound proteins were eluted with a chaotrope solution. Wash (W) and eluate (E) fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Plasminogen was detected with polyclonal antiplasminogen antiserum. Lane NHS, 1:10 diluted serum.

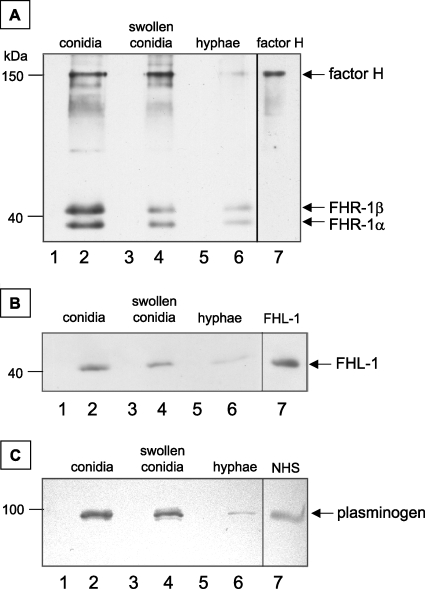

Different developmental forms of A. fumigatus bind to complement regulators.

Conidia of A. fumigatus bound to factor H, FHR-1, FHL-1, and plasminogen. Therefore, we analyzed whether other developmental forms of A. fumigatus, such as swollen conidia and young hyphae, also bind these host immune regulators. The binding intensity of complement regulators was highest for conidia and lower for swollen conidia. Young hyphae from an overnight culture bound to only a small amount of factor H, FHR-1 (Fig. 6A), FHL-1 (Fig. 6B), and plasminogen (Fig. 6C). Thus, specifically conidia, the developmental form of A. fumigatus which is first in contact with the host immune system, acquire immune regulators factor H, FHR-1, FHL-1, and plasminogen from human sera.

FIG. 6.

Binding of factor H and plasminogen to different developmental stages of A. fumigatus. Conidia, swollen conidia, and young hyphae were incubated with NHS and washed, and bound proteins were eluted with a chaotrope solution. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis was performed for the detection of factor H and FHR-1 (A), FHL-1 (B), and plasminogen (C). NHS as well as purified factor H and FHL-1 served as controls.

Surface-bound factor H displays cofactor activity.

We analyzed whether factor H maintains complement-regulating activity when bound to A. fumigatus conidia and thereby inhibits complement activation. Conidia were incubated with factor H, and after extensive washing, purified factor I and C3b were added. As a control, conidia were incubated with factor H and factor I alone. After incubation, the products were separated by SDS-PAGE. The proteolytic cleavage of the α′ chain of C3b was assayed by Western blotting. In the presence of factor I and C3b, factor H-coated conidia mediated the cleavage of C3b. This was concluded from the appearance of the α′-chain fragments with molecular masses of 68 kDa and 43 kDa (Fig. 7A, lane 2). This cleavage pattern is characteristic of factor H-mediated cofactor activity in the factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b (27, 31). Thus, surface-bound factor H maintains cofactor activity.

FIG. 7.

Activity of surface-bound host proteins. (A) Surface-attached factor H mediated complement-regulating activity. Conidia of A. fumigatus were incubated in purified factor H. After extensive washing, factor I (lane 1) or both factor I and C3b (lane 2) were added. Conidia incubated with factor I and C3b in the absence of factor H were used in lane 3. After incubation for 1 h, the supernatant was separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. The positions of the α′ and β chains of C3b are indicated as well as the positions of the α′ 68-kDa and the α′ 43-kDa cleavage products. (B) Plasminogen attached to the conidial surface is accessible to uPA for activation and mediates the cleavage of the chromogenic substrate S-2251. Cleavage of the substrate results in an increase in absorbance at 405 nm.

Activation of surface-bound plasminogen.

Plasminogen needs to be activated to plasmin to display proteolytic activity. uPA mediates the activation of plasminogen to plasmin. The activation and proteolytic activity of conidia-bound plasminogen by uPA were demonstrated using a colorimetric assay. Activated plasminogen cleaves the chromogenic plasmin substrate S-2251, which results in an increase in absorbance. The addition of uPA and S-2251 to plasminogen-coated conidia resulted in the cleavage of the chromogenic substrate. Thus, plasminogen in its surface-bound form can be activated to plasmin and gains proteolytic activity. In probes lacking plasminogen or uPA, no cleavage of the substrate occurred (Fig. 7B). The amount of plasminogen applied was sufficient to saturate all available binding sites on the conidia, as no increase in absorbance was observed when the plasminogen concentration was increased (Fig. 7B). However, when the amount of conidia was doubled, the intensity of the signal also increased.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report a novel mechanism of immune evasion for Aspergillus fumigatus. A. fumigatus conidia bind to the host immune regulators factor H, FHL-1, and FHR-1 as well as plasminogen.

The human innate immune system is essential for the defense against an A. fumigatus infection. Phagocytosis and the killing of conidia by phagocytes are key processes to prevent an infection (4). Therefore, evasion from phagocytosis is likely to allow A. fumigatus a prolonged survival in the human host. The role of the complement system in the defense against A. fumigatus, however, is poorly understood. For A. fumigatus, the lung, as the major site of infection, represents an environment which is different from serum. However, several components of both the alternative and the classical pathways are present in human bronchoalveolar fluid except for C4bp (3). Factor H mRNA (3) was identified in RNA prepared from lung tissue, and type II pneumocytes (cell line A549) secrete factor H (42). Thus, the lung is a site for complement activation, and inactivation can occur in vivo. Moreover, plasminogen and plasminogen activator are also readily available in the human lung (2).

Previously, it was shown that the deposition of C3 correlates with pathogenicity. Conidia of the highly pathogenic species A. fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus bound fewer C3 molecules per unit of conidial surface than conidia of less-pathogenic Aspergillus species (15). Opsonization, however, is important for enhanced phagocytosis (44). Conidia of a white (pksP) mutant of A. fumigatus (28), which bound more C3 molecules per unit of conidial surface than the wild type, also showed a higher phagocytosis rate (45). Thus, complement inactivation appears to contribute to the survival of A. fumigatus in the human host.

Previously it was shown that A. fumigatus conidia activate only the alternative pathway of complement activity, whereas hyphae activate both the alternative and the classical pathway (21). Conidia are the first cells of A. fumigatus which invade the host and which are confronted by the host immune system. Evasion from recognition by the innate immune system is crucial for the survival of the pathogen and the onset of the infection. The binding of host complement regulators by conidia might represent a mechanism to inhibit complement activation. Once supplied with nutrients and water, conidia swell and germinate. Unlike conidia, germlings and hyphae bind only a small amount of factor H. Apparently, interaction partners for factor H are specifically expressed on the conidial surface. During germination, the proteinaceous layer of the conidia is shed, and the properties of the surface change. Thus, it is conceivable that receptors present on conidia are no longer found on hyphae. Nevertheless, hyphae are also protected against the activation of the complement system, since it has been shown that they secrete a complement inhibitory factor (47). This still unidentified low-molecular-weight compound was shown to decrease complement activation.

The use of recombinant mutant proteins of factor H identified two binding sites on factor H and FHL-1 which mediate surface attachment to A. fumigatus. The first domain, shared by factor H and FHL-1, was located within SCRs 1 to 7, and the second site, which is specific to factor H, within SCR 20. Since it is known that heparin also binds to SCR 20 and, as shown here, inhibits the binding of factor H to conidia, the importance of SCR 20 for binding was further underlined. Factor H binds to other pathogenic fungi with the same two binding sites. For C. albicans, it was shown that factor H binds to the surface via SCRs 6 and 7 and via SCRs 19 and 20 (31). With these binding sites, the regulators are oriented with their C-terminal ends to the surfaces of the conidia and the N-terminal complement regulatory regions pointing to the outside (51). This type of attachment allows C3 inactivation in the direct vicinity of the cell surface. As shown here, bound factor H remained functionally active and acted as a cofactor to the factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b.

The acquisition of host proteins, particularly of human complement regulators, seems to represent a central mechanism in immune evasion of human pathogens (for a review, see reference 51). An increasing number of human pathogens which acquire human plasma complement regulators, such as the AP regulators factor H, FHL-1, and FHR-1 as well as the classical pathway regulator C4bp, has been identified. Such organisms include Streptococcus pyogenes (20), S. pneumoniae (33), Borrelia burgdorferi (1, 14, 23), Yersinia enterocolitica (5), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (39, 40), N. meningitidis (38), Echinococcus granulosus (8), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (27), and the human immunodeficiency virus (43). C. albicans (30, 31) binds the three complement regulators factor H, FHL-1, and C4bp. C4bp did not bind to the surfaces of A. fumigatus conidia but did bind to those of A. niger conidia (data not shown). For some pathogens, the microbial binding proteins responsible for the attachment of the regulators have been identified. These include the M protein of S. pyogenes (20); CRASP-1, OspE, and CRASP-2 to -4 of B. burgdorferi (14, 22, 23); the sialylated lipooligosaccharide major outer membrane porin of N. gonorrhoeae (39); the Hic protein of S. pneumoniae (18); Tuf of P. aeruginosa (27); and gp120 and gp41 of the human immunodeficiency virus (43). FHR-1 binding proteins were identified as BbCRASP-3 to -5 for B. burgdorferi (12) and as Tuf for P. aeruginosa (27).

Besides the known regulators of complement activation, another protein was reported to be of importance in immune evasion of microorganisms. Plasminogen can be activated to plasmin by host or microbial plasminogen activators and has proteolytic activity. This activity regulates several physiological processes, e.g., fibrinolysis, the degradation of the extracellular matrix, cell migration, the processing of growth factors, and the formation of metastases of tumors. Plasminogen is bound by various human pathogens, including C. albicans (7), B. hermsii (41), and P. aeruginosa (27). In this study, we show the binding of plasminogen to A. fumigatus conidia. These surface-bound plasminogen molecules could be activated to plasmin and exhibited proteolytic activity.

In conclusion, A. fumigatus conidia bind human complement regulators factor H, FHR-1, FHL-1, and plasminogen. The bound host regulators may contribute to the immune evasion of A. fumigatus and to the inactivation of an activated human complement system. The identification and cloning of A. fumigatus molecules involved in the interaction with and binding to human immune regulators are central and essential aspects of future work, which is likely to result in the identification of new virulence determinants.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the “Grundlagenfonds” of HKI to A.A.B. and P.F.Z. and the Priority Program 1160 (colonization and infection by human-pathogenic fungi) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to A.A.B. and P.F.Z.

Editor: A. Casadevall

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alitalo, A., T. Meri, L. Rämö, T. S. Jokiranta, T. Heikkilä, I. J. T. Seppälä, J. Oksi, M. Viljanen, and S. Meri. 2001. Complement evasion by Borrelia burgdorferi: serum-resistant strains promote C3b inactivation. Infect. Immun. 693685-3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelici, E., C. Contini, M. Spezzano, R. Romani, P. Carfagna, P. Serra, and R. Canipari. 2001. Plasminogen activator production in a rat model of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Microbiol. Immunol. 45605-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolger, M. S., D. S. Ross, H. Jiang, M. M. Frank, A. J. Ghio, D. A. Schwartz, and J. R. Wright. 2007. Complement levels and activity in the normal and LPS-injured lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292L748-L759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brakhage, A. A. 2005. Systemic fungal infections caused by Aspergillus species: epidemiology, infection process and virulence determinants. Curr. Drug Targets 6875-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.China, B., M.-P. Sory, B. T. N′Guyen, M. De Bruyere, and G. R. Cornelis. 1993. Role of the YadA protein in prevention of opsonization of Yersinia enterocolitica by C3b molecules. Infect. Immun. 613129-3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung, K. M., M. K. Liszewski, G. Nybakken, A. E. Davis, R. R. Townsend, D. H. Fremont, J. P. Atkinson, and M. S. Diamond. 2006. West Nile virus nonstructural protein NS1 inhibits complement activation by binding the regulatory protein factor H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10319111-19116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowe, J. D., I. K. Sievwright, G. C. Auld, N. R. Moore, N. A. Gow, and N. A. Booth. 2003. Candida albicans binds human plasminogen: identification of eight plasminogen-binding proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 471637-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz, A., A. Ferreira, and R. B. Sim. 1997. Complement evasion by Echinococcus granulosus: sequestration of host factor H in the hydatid cyst wall. J. Immunol. 1583779-3786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farries, T. C., T. Seya, R. A. Harrison, and J. P. Atkinson. 1990. Competition for binding sites on C3b by CR1, CR2, MCP, factor B and Factor H. Complement Inflamm. 730-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friese, M. A., J. Hellwage, T. S. Jokiranta, S. Meri, H. H. Peter, H. Eibel, and P. F. Zipfel. 1999. FHL-1/reconectin and factor H: two human complement regulators which are encoded by the same gene are differently expressed and regulated. Mol. Immunol. 36809-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammerschmidt, S., V. Agarwal, A. Kunert, S. Haelbich, C. Skerka, and P. F. Zipfel. 2007. The host immune regulator factor H interacts via two contact sites with the PspC protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae and mediates adhesion to host epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 1785848-5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haupt, K., P. Kraiczy, R. Wallich, V. Brade, C. Skerka, and P. F. Zipfel. 2007. Binding of human factor H-related protein 1 to serum-resistant Borrelia burgdorferi is mediated by borrelial complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins. J. Infect. Dis. 196124-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellwage, J., T. S. Jokiranta, V. Koistinen, O. Vaarala, S. Meri, and P. F. Zipfel. 1999. Functional properties of complement factor H-related proteins FHR-3 and FHR-4: binding to the C3d region of C3b and differential regulation by heparin. FEBS Lett. 462345-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellwage, J., T. Meri, T. Heikkila, A. Alitalo, J. Panelius, P. Lahdenne, I. J. Seppala, and S. Meri. 2001. The complement regulator factor H binds to the surface protein OspE of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 2768427-8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henwick, S., S. V. Hetherington, and C. C. Patrick. 1993. Complement binding to Aspergillus conidia correlates with pathogenicity. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 12227-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horstmann, R. D., H. J. Sievertsen, J. Knobloch, and V. A. Fischetti. 1988. Antiphagocytic activity of streptococcal M protein: selective binding of complement control protein factor H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 851657-1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hovis, K. M., J. P. Jones, T. Sadlon, G. Raval, D. L. Gordon, and R. T. Marconi. 2006. Molecular analyses of the interaction of Borrelia hermsii FhbA with the complement regulatory proteins factor H and factor H-like protein 1. Infect. Immun. 742007-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janulczyk, R., F. Iannelli, A. G. Sjoholm, G. Pozzi, and L. Bjorck. 2000. Hic, a novel surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae that interferes with complement function. J. Biol. Chem. 27537257-37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnsson, E., K. Berggard, H. Kotarsky, J. Hellwage, P. F. Zipfel, U. Sjobring, and G. Lindahl. 1998. Role of the hypervariable region in streptococcal M proteins: binding of a human complement inhibitor. J. Immunol. 1614894-4901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotarsky, H., J. Hellwage, E. Johnsson, C. Skerka, H. G. Svensson, G. Lindahl, U. Sjobring, and P. F. Zipfel. 1998. Identification of a domain in human factor H and factor H-like protein-1 required for the interaction with streptococcal M proteins. J. Immunol. 1603349-3354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozel, T. R., M. A. Wilson, T. P. Farrell, and S. M. Levitz. 1989. Activation of C3 and binding to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia and hyphae. Infect. Immun. 573412-3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraiczy, P., C. Skerka, V. Brade, and P. F. Zipfel. 2001. Further characterization of complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 697800-7809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraiczy, P., C. Skerka, M. Kirschfink, V. Brade, and P. F. Zipfel. 2001. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi by acquisition of human complement regulators FHL-1/reconectin and factor H. Eur. J. Immunol. 311674-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kühn, S., C. Skerka, and P. F. Zipfel. 1995. Mapping of the complement regulatory domains in the human factor H-like protein 1 and in factor H1. J. Immunol. 1555663-5670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kühn, S., and P. F. Zipfel. 1995. The baculovirus expression vector pBSV-8His directs secretion of histidine-tagged proteins. Gene 162225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kühn, S., and P. F. Zipfel. 1996. Mapping of the domains required for decay acceleration activity of the human factor H-like protein 1 and factor H. Eur. J. Immunol. 262383-2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunert, A., J. Losse, C. Gruszin, M. Hühn, K. Kaendler, S. Mikkat, D. Volke, R. Hoffmann, T. S. Jokiranta, H. Seeberger, U. Moellmann, J. Hellwage, and P. F. Zipfel. 2007. Immune evasion of the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa: elongation factor Tuf is a factor H and plasminogen binding protein. J. Immunol. 1792979-2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langfelder, K., B. Jahn, H. Gehringer, A. Schmidt, G. Wanner, and A. A. Brakhage. 1998. Identification of a polyketide synthase gene (pksP) of Aspergillus fumigatus involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berlin) 18779-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDowell, J. V., J. Lankford, L. Stamm, T. Sadlon, D. L. Gordon, and R. T. Marconi. 2005. Demonstration of factor H-like protein 1 binding to Treponema denticola, a pathogen associated with periodontal disease in humans. Infect. Immun. 737126-7132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meri, T., A. M. Blom, A. Hartmann, D. Lenk, S. Meri, and P. F. Zipfel. 2004. The hyphal and yeast forms of Candida albicans bind the complement regulator C4b-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 726633-6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meri, T., A. Hartmann, D. Lenk, R. Eck, R. Würzner, J. Hellwage, S. Meri, and P. F. Zipfel. 2002. The yeast Candida albicans binds complement regulators factor H and FHL-1. Infect. Immun. 705185-5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Misasi, R., H. P. Huemer, W. Schwaeble, E. Solder, C. Larcher, and M. P. Dierich. 1989. Human complement factor H: an additional gene product of 43 kDa isolated from human plasma shows cofactor activity for the cleavage of the third component of complement. Eur. J. Immunol. 191765-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neeleman, C., S. P. M. Geelen, P. C. Aerts, M. R. Daha, T. E. Mollnes, J. J. Roord, G. Posthuma, H. van Dijk, and A. Fleer. 1999. Resistance to both complement activation and phagocytosis in type 3 pneumococci is mediated by the binding of complement regulatory protein factor H. Infect. Immun. 674517-4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oppermann, M., T. Manuelian, M. Jozsi, E. Brandt, T. S. Jokiranta, S. Heinen, S. Meri, C. Skerka, O. Gotze, and P. F. Zipfel. 2006. The C-terminus of complement regulator factor H mediates target recognition: evidence for a compact conformation of the native protein. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 144342-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ormsby, R. J., T. S. Jokiranta, T. G. Duthy, K. M. Griggs, T. A. Sadlon, E. Giannakis, and D. L. Gordon. 2006. Localization of the third heparin-binding site in the human complement regulator factor H1. Mol. Immunol. 431624-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pangburn, M. K., R. D. Schreiber, and H. J. Muller-Eberhard. 1977. Human complement C3b inactivator: isolation, characterization, and demonstration of an absolute requirement for the serum protein beta1H for cleavage of C3b and C4b in solution. J. Exp. Med. 146257-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2004. Rare and emerging opportunistic fungal pathogens: concern for resistance beyond Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 424419-4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ram, S., F. G. Mackinnon, S. Gulati, D. P. McQuillen, U. Vogel, M. Frosch, C. Elkins, H. K. Guttormsen, L. M. Wetzler, M. Oppermann, M. K. Pangburn, and P. A. Rice. 1999. The contrasting mechanisms of serum resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and group B Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Immunol. 36915-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ram, S., D. P. McQuillen, S. Gulati, C. Elkins, M. K. Pangburn, and P. A. Rice. 1998. Binding of complement factor H to loop 5 of porin protein 1A: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of nonsialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Exp. Med. 188671-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ram, S., A. K. Sharma, S. D. Simpson, S. Gulati, D. P. McQuillen, M. K. Pangburn, and P. A. Rice. 1998. A novel sialic acid binding site on factor H mediates serum resistance of sialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Exp. Med. 187743-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossmann, E., P. Kraiczy, P. Herzberger, C. Skerka, M. Kirschfink, M. M. Simon, P. F. Zipfel, and R. Wallich. 2007. Dual binding specificity of a Borrelia hermsii-associated complement regulator-acquiring surface protein for factor H and plasminogen discloses a putative virulence factor of relapsing fever spirochetes. J. Immunol. 1787292-7301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothman, B. L., M. Merrow, A. Despins, T. Kennedy, and D. L. Kreutzer. 1989. Effect of lipopolysaccharide on C3 and C5 production by human lung cells. J. Immunol. 143196-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoiber, H., I. Frank, M. Spruth, M. Schwendinger, B. Mullauer, J. M. Windisch, R. Schneider, H. Katinger, I. Ando, and M. P. Dierich. 1997. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection in vitro by monoclonal antibodies to the complement receptor type 3 (CR3): an accessory role for CR3 during virus entry? Mol. Immunol. 34855-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sturtevant, J., and J. P. Latgé. 1992. Participation of complement in the phagocytosis of the conidia of Aspergillus fumigatus by human polymorphonuclear cells. J. Infect. Dis. 166580-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsai, H.-F., Y. C. Chang, R. G. Washburn, M. H. Wheeler, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1998. The developmentally regulated alb1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus: its role in modulation of conidial morphology and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 1803031-3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Lookeren Campagne, M., C. Wiesmann, and E. J. Brown. 2007. Macrophage complement receptors and pathogen clearance. Cell. Microbiol. 92095-2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Washburn, R. G., D. J. DeHart, D. E. Agwu, B. J. Bryant-Varela, and N. C. Julian. 1990. Aspergillus fumigatus complement inhibitor: production, characterization, and purification by hydrophobic interaction and thin-layer chromatography. Infect. Immun. 583508-3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei, L., V. Pandiripally, E. Gregory, M. Clymer, and D. Cue. 2005. Impact of the SpeB protease on binding of the complement regulatory proteins factor H and factor H-like protein 1 by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 732040-2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiler, J. M., M. R. Daha, K. F. Austen, and D. T. Fearon. 1976. Control of the amplification convertase of complement by the plasma protein beta1H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 733268-3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zipfel, P. F., and C. Skerka. 1999. FHL-1/reconectin: a human complement and immune regulator with cell-adhesive function. Immunol. Today 20135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zipfel, P. F., R. Würzner, and C. Skerka. 2007. Complement evasion of pathogens: common strategies are shared by diverse organisms. Mol. Immunol. 443850-3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]