Abstract

Two galactosyl transferases can apparently account for the full biosynthesis of the cell wall galactan of mycobacteria. Evidence is presented based on enzymatic incubations with purified natural and synthetic galactofuranose (Galf) acceptors that the recombinant galactofuranosyl transferase, GlfT1, from Mycobacterium smegmatis, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3782 ortholog known to be involved in the initial steps of galactan formation, harbors dual β-(1→4) and β-(1→5) Galf transferase activities and that the product of the enzyme, decaprenyl-P-P-GlcNAc-Rha-Galf-Galf, serves as a direct substrate for full polymerization catalyzed by another bifunctional Galf transferase, GlfT2, the Rv3808c enzyme.

The mycobacterial cell wall—including the essential, covalently linked complex of peptidoglycan, heteropolymeric arabinogalactan, and highly hydrophobic mycolic acids—is responsible for many of the pathophysiological features of members of the Mycobacterium genus (9). Several antituberculosis drugs affect the formation of this complex. Isoniazid, ethionamide, thiocarlide, and thiacetazone inhibit mycolic acid synthesis (14, 29, 30, 36, 38); ethambutol specifically disrupts the synthesis of arabinan (20, 24, 35, 39); and d-cycloserine, an inhibitor of peptidoglycan synthesis (11), has some clinical utility. However, drug resistance, particularly the multiple and extensive forms, is of pressing public health concern (15, 31), presaging the need for a broader array of targets and drugs affecting both cell wall synthesis and other aspects of mycobacterial metabolism. However, our understanding of the synthesis of the mycobacterial cell wall is elementary compared to that of other bacteria.

The initiation point for arabinogalactan biogenesis is the mycobacterial version of the bacterial carrier lipid, bactoprenol, identified as decaprenyl phosphate (C50-P) (10), and the sequential addition of GlcNAc-P, rhamnose (Rha), and single galactofuranose (Galf) units, donated by the appropriate nucleotide sugars (23, 25) (Fig. 1). At some stage, the arabinofuranose (Araf) units are added, donated not by a nucleotide sugar but a lipid carrier, C50-P-Araf (20, 39). Several of the responsible glycosyl transferases taking part in this process have been identified (1, 3, 5, 18, 19, 25, 26, 32, 34).

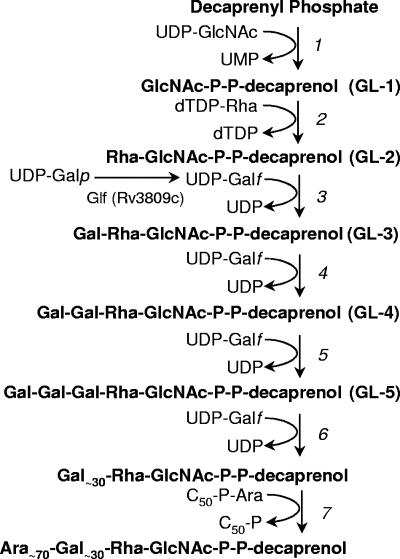

FIG. 1.

Pathway for the biosynthesis of mycobacterial arabinogalactan. The sequence of reactions is based on identification of GL-1 through GL-5 and the lipid-linked arabinogalactan polymer in cell-free systems containing mycobacterial membranes and cell wall fractions (21-23, 25). GlcNAc-1-P transferase WecA (Rv1302) is proposed to be responsible for step 1 (21); the rhamnosyl transferase WbbL (Rv3265) catalyzes step 2 (26). Subsequent reaction 3 and/or 4 is proposed in this study and previously (22) to be catalyzed by Rv3782. Step 6 represents a series of galactofuranosyl additions catalyzed by Rv3808c. Several arabinosyl transferases involved in reactions under step 7 have been described, such as the Emb proteins (3), AftA (1), and AftB (34).

We recently described the galactofuranosyl transferase, Rv3782, responsible for attaching the first and, perhaps, the second Galf unit to the C50-P-P-GlcNAc-Rha acceptor (22). Due to its role in the initiation of galactan formation, we now name it galactofuranosyl transferase 1 (GlfT1). Previously, yet another galactofuranosyl transferase, Rv3808c (originally called GlfT but now named GlfT2), was recognized and proved to be bifunctional in that it was responsible for the formation of the bulk of the galactan, containing alternating 5- and 6-linked β-Galf units (19, 25, 32). In the present study, we examine the precise roles of GlfT1 and GlfT2 in mycobacterial cell wall galactan synthesis through the application of in vitro reactions with purified natural acceptors, synthetic products emulating the natural substrates, and the recombinant enzymes expressed in Escherichia coli.

Cloning, expression, and activity of the GlfT1 ortholog from Mycobacterium smegmatis.

Attempts to produce a soluble form of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3782 enzyme in E. coli were unsuccessful, apparently due to toxic effects, and the yields of pure active protein from an overproducing strain of M. smegmatis were too low to allow further biochemical studies. Instead the M. smegmatis ortholog, corresponding to the gene MSMEG_6367 (www.tigr.org), was cloned and expressed in E. coli; the two orthologous GlfT1 proteins are 90.7% similar and have 76.8% sequence identity (ClustalX, version 1.8). The glfT1 genes are located within the conserved arabinogalactan biosynthetic regions in M. smegmatis mc2155 and M. tuberculosis H37Rv (4), in the center of predicted operons comprised of three genes, where the first one encodes a nucleotide binding protein (MSMEG_6366 and Rv3781 orthologs) and the last one encodes a membrane-spanning protein (MSMEG_6369 and Rv3783 orthologs) of the ABC (ATP-binding cassette) transport type (6). The glfT1 gene from M. smegmatis mc2155 was amplified based on the oligonucleotide primers 5′-GCACCAACATATGACGCACACTGAGGTCGTCTG-3′ and 5′-CCCAAGCTTTCATCGCTGGAACCTTTCGCGTC-3′, containing NdeI and HindIII restriction sites. The PCR fragment (0.93 kb) was digested and ligated into the similarly digested pVV2 and pET28a vectors for expression in M. smegmatis mc2155 and E. coli BL21(DE3) (13). Production of the MSMEG_6367 protein with the N-terminal six-histidine fusion tag was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting. Assays for Galf transferase activity (22) with the recombinant MSMEG_6367 protein overexpressed in M. smegmatis demonstrated increased synthesis of C50-P-P-GlcNAc-Rha-Galf-Galf (glycolipid 4; GL-4) (data not shown), confirming identical functions for the two orthologous GlfT1 proteins, Rv3782 and MSMEG_6367.

GlfT1 has dual β-(1→4) and β-(1→5) galactofuranosyl transferase activities.

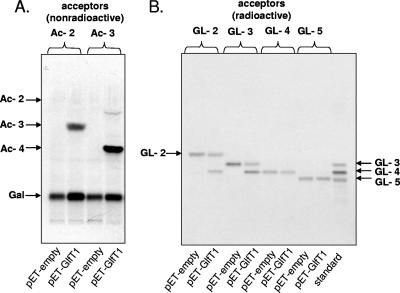

Previous studies had shown that GlfT1 from M. tuberculosis could catalyze the synthesis of both GL-3 (C50-P-P-GlcNAc-Rha-Galf) and GL-4, attributing both β-(1→4) and β-(1→5) galactofuranosyl transferase activities to the one enzyme (22). However, efforts to directly confirm this dual activity with the purified putative substrates (GL-2 and GL-3) and purified recombinant Rv3782 enzyme were not successful (22). In the present instance, the overproducing strain, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET28a-MSMEG_6367, and a control culture with the empty vector were induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), the cells were harvested and disintegrated by probe sonication as described previously (22), and the supernatant from centrifugation was used as a source of GlfT1. The synthetic products, Ac-2, Ac-3, and Ac-4 (Fig. 2), analogs of GL-2, GL-3, and GL-4, served as putative acceptors. In addition to the above-mentioned substrates at 4 mM concentration each, the reaction mixtures contained 6.25 mM NADH, 62.5 μM ATP, UDP-[U-14C]Galp (278 mCi/mmol; 0.25 μCi), 20 μg of UDP-Galp mutase (25), and 50-μl aliquots of the cell lysate from the control or overproducing strain of GlfT1 in a final volume of 80 μl (22). The reactions were stopped by the addition of CHCl3-CH3OH (2:1) to yield the organic phase of a biphasic solution (16). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and autoradiography of the reaction products revealed that both Ac-2 and Ac-3, emulating GL-2 and GL-3, were efficient substrates for recombinant GlfT1, converting them to radiolabeled Ac-3 and Ac-4, respectively (Fig. 3A). However, Ac-4, reflective of GL-4, was not effective as an acceptor of [14C]Gal under the reaction conditions (results not shown), indicating that GlfT1 could not catalyze subsequent galactan chain extension. Moreover, when the native glycolipids, GL-2, GL-3, GL-4, and GL-5 (isolated as described in reference 22) were incorporated into similar assays, both GL-2 and GL-3 were readily converted to GL-4 (Fig. 3B); however, as in the case of the synthetic acceptor Ac-4, GL-4 was not an effective substrate for GlfT1. Similarly, GL-5 did not serve as an acceptor for galactofuranosyl transfer catalyzed by GlfT1 (Fig. 3B).

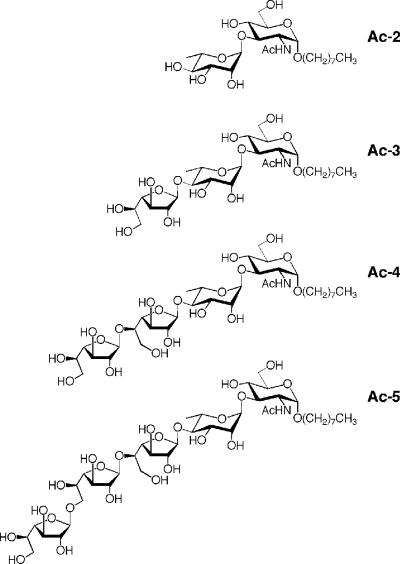

FIG. 2.

Structures of the synthetic acceptors Ac-2, Ac-3, Ac-4, and Ac-5. Oligosaccharide portions of Ac-2 to Ac-5 match the structures of the natural intermediates in galactan biosynthesis, namely GL-2, GL-3, GL-4, and GL-5. Abbreviations: Ac-2, octyl α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→3)-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-α-d-glucopyranoside; Ac-3, octyl β-d-galactofuranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→3)-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-α-d-glucopyrano-side; Ac-4, octyl β-d-galactofuranosyl-(1→5)-β-d-galactofuranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→3)-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-α-d-glucopyranoside; Ac-5, octyl β-d-galactofuranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-galactofuranosyl-(1→5)-β-d-galactofuranosyl-(1→4)-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→3)-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-α-d-glucopyranoside. Synthesis of these acceptors will be described by Lowary et al. (unpublished data).

FIG. 3.

Recognition of the dual β-(1→4) and β-(1→5) Galf transferase activities of GlfT1. The synthetic acceptors Ac-2 and Ac-3 (A) and the native substrates GL-2, GL-3, GL-4, and GL-5 (B) were used as the acceptors of galactofuranosyl residues in the reaction catalyzed by GlfT1 expressed in the heterologous host, E. coli. The positions of Ac-2, Ac-3, and Ac-4 substrates on TLC plate were visualized by staining with α-naphthol.

GlfT2 catalyzes the formation of GL-5 and further galactan polymerization.

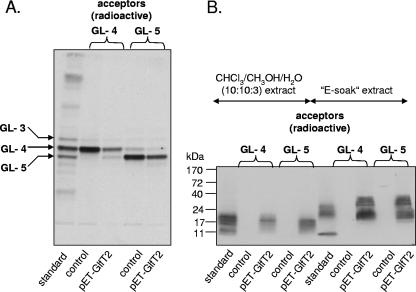

Following recognition of the role of GlfT1 in GL-3 and GL-4 synthesis and previous evidence that GlfT2, the Rv3808c enzyme, can catalyze the formation of the C50-P-P-GlcNAc-Rha-linked galactan polymer with its inherent alternating β-(1→4) Galf and β-(1→5) Galf units, the question arose as to the initiation of the polymerization events. Specifically, could GL-4 and its synthetic analogue Ac-4 give rise to GL-5/Ac-5 and the subsequent polymer? We investigated this question through enzyme incubations containing GlfT2 from M. tuberculosis overexpressed in E. coli (32), radiolabeled GL-4 or GL-5 (2,000 dpm each), and 0.2 mM cold UDP-Galp instead of the radioactive counterpart. Extraction of the reaction products with CHCl3-CH3OH (2:1) showed consumption of the original substrates GL-4 and GL-5 in the reaction mixtures containing the overexpressed GlfT2 (Fig. 4A). Further extraction with solvents more polar than CHCl3-CH3OH (2:1), namely CHCl3-CH3OH-H2O (10:10:3) (33) and “E-soak” (water-ethanol-diethyl ether-pyridine-ammonium hydroxide at 5:15:5:1:0.017) (2), removed the C50-P-P-GlcNAc-Rha-based galactan polymers, which were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 4B). Clearly, GlfT2 catalyzed the conversion of GL-4 to GL-5, and both substrates were suitable for galactan polymerization (Fig. 4B). When purified GL-2 or GL-3 was used in a similar experiment, galactan buildup did not take place (data not shown). Moreover, Ac-4 and Ac-5, the synthetic equivalents of GL-4 and GL-5, proved to be ready acceptors of [14C]Gal provided by UDP-[U-14C]Galp in the standard reaction mixture containing recombinant GlfT2 (32), whereas Ac-2 and Ac-3 were not effective substrates, as detailed below. The abilities of Ac-2 to -5 to serve as substrates for GlfT2 were as follows, as measured by transfer of radiolabeled Galf to each potential acceptor with recombinant GlfT2, as described previously (32): Ac-2, 732 dpm; Ac-3, 911 dpm; Ac-4, 18,706 dpm; and Ac-5, 369,378 dpm. With no acceptor, the result was 985 dpm. Therefore, these data further support the case that GlfT2 catalyzes the addition of the third and subsequent Galf residues, but not the first two, to the lipid template in galactan synthesis.

FIG. 4.

Both glycolipids GL-4 and GL-5 serve as substrates for GlfT2. Natural substrates GL-4 and GL-5 were used as acceptors of galactofuranosyl residues in the reaction catalyzed by GlfT2 expressed in the heterologous host, E. coli. The reaction mixtures were subjected to series of extractions, as described. (A) TLC of glycolipid fractions followed by autoradiography. (B) SDS-PAGE of lipid-linked galactan polymer followed by Western blotting and autoradiography. Lanes labeled “control” represent samples containing the host E. coli strain. Lanes labeled “standard” represent fractions extracted from reaction mixture containing membranes and cell wall from M. smegmatis mc2155 and UDP-[U-14C]Galp as a tracer for production of galactan intermediates (25).

Conclusions.

Experimental evidence presented in this paper resolves several questions raised in our previous work (22, 32). First, this study shows that the galactosyltransferase GlfT1 from M. smegmatis, the Rv3782 ortholog, initiates galactan synthesis on the C50-P-P-GlcNAc-Rha acceptor and is endowed with dual, β-(1→4) and β-(1→5) Galf transferase activities. Second, the data strongly suggest that the action of GlfT1 is directly followed by that of another bifunctional enzyme, GlfT2, the Rv3808c protein, apparently responsible for the majority of galactan polymerization. These enzymes thus represent further examples of a growing number of glycosyl transferases that harbor two distinct transferase activities on a single polypeptide chain (7, 8, 12, 19, 25, 27, 28, 32, 37), belying the early “one enzyme, one linkage” hypothesis (17). Thus, it would seem from the present evidence that complete synthesis of mycobacterial galactan can be catalyzed by but two enzymes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under contract no. RPEU-0012-06, Slovak Grant Agency VEGA 1/2324/05; by the European Commission under contract LSHP-CT-2005-018923 NM4TB (K.M.); by NIH (NIAID) grants AIDS-FIRCA TW 006487 (P.J.B. and K.M.) and AI-18357 (P.J.B.); and by the Alberta Ingenuity Centre for Carbohydrate Science and The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (T.L.L.).

We thank Michael McNeil, Sebabrata Mahapatra, and Dean Crick for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderwick, L. J., M. Seidel, H. Sahm, G. S. Besra, and L. Eggeling. 2006. Identification of a novel arabinofuranosyltransferase (AftA) involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 28115653-15661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus, W. W., and R. L. Lester. 1972. Turnover of inositol and phosphorus containing lipids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: extracellular accumulation of glycerophosphorylinositol derived from phosphatidylinositol. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 151483-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belanger, A. E., G. S. Besra, M. E. Ford, K. Mikusova, J. T. Belisle, P. J. Brennan, and J. M. Inamine. 1996. The embAB genes of Mycobacterium avium encode an arabinosyl transferase involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis that is the target for the antimycobacterial drug ethambutol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9311919-11924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belanger, A. E., and J. M. Inamine. 2000. Genetics of cell wall biosynthesis, p. 191-202. In G. F. Hatfull and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. (ed.), Molecular genetics of mycobacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 5.Berg, S., D. Kaur, M. Jackson, and P. J. Brennan. 2007. The glycosyltransferases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis—roles in the synthesis of arabinogalactan, lipoarabinomannan, and other glycoconjugates. Glycobiology 1735R-56R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braibant, M., P. Gilot, and J. Content. 2000. The ATP binding cassette (ABC) transport systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24449-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartee, R. T., W. T. Forsee, J. S. Schutzbach, and J. Yother. 2000. Mechanism of type 3 capsular polysaccharide synthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 2753907-3914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke, B. R., D. Bronner, W. J. Keenleyside, W. B. Severn, J. C. Richards, and C. Whitfield. 1995. Role of Rfe and RfbF in the initiation of biosynthesis of d-galactan I, the lipopolysaccharide O antigen from Klebsiella pneumoniae serotype O1. J. Bacteriol. 1775411-5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crick, D. C., S. Mahapatra, and P. J. Brennan. 2001. Biosynthesis of the arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Glycobiology 11107R-118R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crick, D. C., M. C. Schulbach, E. E. Zink, M. Macchia, S. Barontini, G. S. Besra, and P. J. Brennan. 2000. Polyprenyl phosphate biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 1825771-5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David, H. L., K. Takayama, and D. S. Goldman. 1969. Susceptibility of mycobacterial D-alanyl-D-alanine synthetase to D-cycloserine. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 100579-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeAngelis, P. L. 1999. Molecular directionality of polysaccharide polymerization by the Pasteurella multocida hyaluronan synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 27426557-26562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhiman, R. K., M. C. Schulbach, S. Mahapatra, A. R. Baulard, V. Vissa, P. J. Brennan, and D. C. Crick. 2004. Identification of a novel class of omega,E,E-farnesyl diphosphate synthase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Lipid Res. 451140-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dover, L. G., A. Alahari, P. Gratraud, J. M. Gomes, V. Bhowruth, R. C. Reynolds, G. S. Besra, and L. Kremer. 2007. EthA, a common activator of thiocarbamide-containing drugs acting on different mycobacterial targets. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 511055-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dye, C. 2006. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Lancet 367938-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folch, J., M. Lees, and G. H. Sloane Stanley. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226497-509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagopian, A., and E. H. Eylar. 1968. Glycoprotein biosynthesis: the basic protein encephalitogen from bovine spinal cord, a receptor for the polypeptidyl:N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase from bovine submaxillary glands. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 126785-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancock, I. C., S. Carman, G. S. Besra, P. J. Brennan, and E. Waite. 2002. Ligation of arabinogalactan to peptidoglycan in the cell wall of Mycobacterium smegmatis requires concomitant synthesis of the two wall polymers. Microbiology 1483059-3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kremer, L., L. G. Dover, C. Morehouse, P. Hitchin, M. Everett, H. R. Morris, A. Dell, P. J. Brennan, M. R. McNeil, C. Flaherty, K. Duncan, and G. S. Besra. 2001. Galactan biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Identification of a bifunctional UDP-galactofuranosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 27626430-26440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, R. E., K. Mikusova, P. J. Brennan, and G. S. Besra. 1995. Synthesis of the mycobacterial arabinose donor beta-D-arabinofuranosyl-1-monophosphoryldecaprenol, development of a basic arabinosyl-transferase assay, and identification of ethambutol as an arabinosyl transferase inhibitor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 11711829-11832. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNeil, M. 1999. Arabinogalactan in mycobacteria: structure, biosynthesis, and genetics. CRS Press, Washington, DC.

- 22.Mikušová, K., M. Beláňová, J. Korduláková, K. Honda, M. R. McNeil, S. Mahapatra, D. C. Crick, and P. J. Brennan. 2006. Identification of a novel galactosyl transferase involved in biosynthesis of the mycobacterial cell wall. J. Bacteriol. 1886592-6598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikusova, K., M. Mikus, G. S. Besra, I. Hancock, and P. J. Brennan. 1996. Biosynthesis of the linkage region of the mycobacterial cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 2717820-7828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikuśová, K., R. A. Slayden, G. S. Besra, and P. J. Brennan. 1995. Biogenesis of the mycobacterial cell wall and the site of action of ethambutol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 392484-2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikusova, K., T. Yagi, R. Stern, M. R. McNeil, G. S. Besra, D. C. Crick, and P. J. Brennan. 2000. Biosynthesis of the galactan component of the mycobacterial cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 27533890-33897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mills, J. A., K. Motichka, M. Jucker, H. P. Wu, B. C. Uhlik, R. J. Stern, M. S. Scherman, V. D. Vissa, F. Pan, M. Kundu, Y. F. Ma, and M. McNeil. 2004. Inactivation of the mycobacterial rhamnosyltransferase, which is needed for the formation of the arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan linker, leads to irreversible loss of viability. J. Biol. Chem. 27943540-43546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Reilly, M. K., G. Zhang, and B. Imperiali. 2006. In vitro evidence for the dual function of Alg2 and Alg11: essential mannosyltransferases in N-linked glycoprotein biosynthesis. Biochemistry 459593-9603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petit, C., G. P. Rigg, C. Pazzani, A. Smith, V. Sieberth, M. Stevens, G. Boulnois, K. Jann, and I. S. Roberts. 1995. Region 2 of the Escherichia coli K5 capsule gene cluster encoding proteins for the biosynthesis of the K5 polysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 17611-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phetsuksiri, B., A. R. Baulard, A. M. Cooper, D. E. Minnikin, J. D. Douglas, G. S. Besra, and P. J. Brennan. 1999. Antimycobacterial activities of isoxyl and new derivatives through the inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 431042-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phetsuksiri, B., M. Jackson, H. Scherman, M. McNeil, G. S. Besra, A. R. Baulard, R. A. Slayden, A. E. DeBarber, C. E. Barry III, M. S. Baird, D. C. Crick, and P. J. Brennan. 2003. Unique mechanism of action of the thiourea drug isoxyl on Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 27853123-53130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raviglione, M. C., and I. M. Smith. 2007. XDR tuberculosis—implications for global public health. N. Engl. J. Med. 356656-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rose, N. L., G. C. Completo, S. J. Lin, M. McNeil, M. M. Palcic, and T. L. Lowary. 2006. Expression, purification, and characterization of a galactofuranosyltransferase involved in Mycobacterium tuberculosis arabinogalactan biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1286721-6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rush, J. S., J. G. Shelling, N. S. Zingg, P. H. Ray, and C. J. Waechter. 1993. Mannosylphosphoryldolichol-mediated reactions in oligosaccharide-P-P-dolichol biosynthesis. Recognition of the saturated alpha-isoprene unit of the mannosyl donor by pig brain mannosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 26813110-13117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seidel, M., L. J. Alderwick, H. L. Birch, H. Sahm, L. Eggeling, and G. S. Besra. 2007. Identification of a novel arabinofuranosyltransferase AftB involved in a terminal step of cell wall arabinan biosynthesis in Corynebacterianeae, such as Corynebacterium glutamicum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 28214729-14740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takayama, K., and J. O. Kilburn. 1989. Inhibition of synthesis of arabinogalactan by ethambutol in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 331493-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takayama, K., L. Wang, and H. L. David. 1972. Effect of isoniazid on the in vivo mycolic acid synthesis, cell growth, and viability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 229-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weigel, P. H., V. C. Hascall, and M. Tammi. 1997. Hyaluronan synthases. J. Biol. Chem. 27213997-14000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winder, F. G., P. B. Collins, and D. Whelan. 1971. Effects of ethionamide and isoxyl on mycolic acid synthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis BCG. J. Gen. Microbiol. 66379-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolucka, B. A., M. R. McNeil, E. de Hoffmann, T. Chojnacki, and P. J. Brennan. 1994. Recognition of the lipid intermediate for arabinogalactan/arabinomannan biosynthesis and its relation to the mode of action of ethambutol on mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 26923328-23335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]