Abstract

Yersinia strains frequently harbor plasmids, of which the virulence plasmid pYV, indigenous in pathogenic strains, has been thoroughly characterized during the last decades. Yet, it has been unknown whether the nonconjugative pYV can be transferred by helper plasmids naturally occurring in this genus. We have isolated the conjugative plasmids pYE854 (95.5 kb) and pYE966 (70 kb) from a nonpathogenic and a pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strain, respectively, and demonstrate that both plasmids are able to mobilize pYV. The complete sequence of pYE854 has been determined. The transfer proteins and oriT of the plasmid reveal similarities to the F factor. However, the pYE854 replicon does not belong to the IncF group and is more closely related to a plasmid of gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid pYE966 is very similar to pYE854 but lacks two DNA regions of the larger plasmid that are dispensable for conjugation.

There is only scarce information available about self-transmissible plasmids in Yersinia. All pathogenic Yersinia strains harbor a conserved nonconjugative 70-kb virulence plasmid (pYV) encoding a type III secretion/transfer system and Yops (Yersinia outer proteins), which play a major role in virulence (10). Loss of the plasmid leads to a loss of virulence (42). Since the plasmid contains a gene for a lipoprotein that is 80% identical with the TraT proteins of F and R100, it has been suggested that pYV at one time was a conjugative plasmid (1, 7). Moreover, pYV of Yersinia pestis can be mobilized in Escherichia coli by the F factor, indicating that it contains a functional transfer origin (oriT). Allen et al. (1) identified a recombinant plasmid containing a 5.5-kb fragment of pYV which was efficiently mobilized by F. The restriction fragment was mapped and assigned to be part of the pYV low-calcium response (lcr) region. Yet the oriT sequence of this plasmid has not been determined. The lcr region of the Yersinia virulence plasmid is conserved in the three medically important species, which implies that the pYV plasmids of all pathogenic Yersinia strains are probably mobilizable. As F is not common in Yersinia, the question arises whether endogenous Yersinia plasmids are also able to mobilize pYV. Cornelis et al. (9) reported on a conjugative lac plasmid that is freely transmissible between strains of Yersinia enterocolitica and E. coli. Other authors described self-transmissible R plasmids in Yersinia that confer resistance against various antibiotics (20, 23, 24, 35). The conjugation of a streptomycin resistance plasmid between E. coli and Y. pestis was even demonstrated in the flea midgut (32). Strauch et al. (48) analyzed a recombinant cosmid containing the conjugative transfer system of a cryptic Y. enterocolitica plasmid. However, none of these plasmids was investigated in terms of its potential to mobilize pYV. Furthermore, sequence data disclosing the relationship of the Yersinia plasmids to other plasmids are missing. This lack of knowledge prompted us to screen our Yersinia strain collection for the presence of large plasmids that were marked by antibiotic resistance genes and to use them for mating experiments. Two related self-transmissible plasmids have been isolated: pYE854 (95.5 kb) from the nonpathogenic Y. enterocolitica serogroup O:5 biogroup 1A strain 29854 and pYE966 (approximately 70 kb) from the pathogenic Y. enterocolitica serogroup O:5,27 biogroup 2 strain 966/89. Basic characteristics of the plasmids have been previously described (29).

Here, we present the complete sequence analysis of plasmid pYE854 and data on the conjugative properties of the plasmid, including its capability to mobilize the Yersinia virulence plasmid pYV. The study was undertaken to assess the potential for pYV dissemination in Yersinia populations. Y. enterocolitica is a heterogenous species consisting of approximately 70 serogroups, of which only some (O:3, O:8, O:9, O:5,27) are known to be pathogenic in humans (4). Reports describing pYV in environmental Yersinia strains are yet not available, but some strains harbor plasmids displaying homologies to pYV (33). We therefore wanted to find out whether gene exchange by conjugation might be common between Yersinia strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains DH5α (51) and Genehogs (Invitrogen) were used as hosts for cloning procedures. All strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. Apart from Yersinia strains, which were cultivated at 28°C, all strains were incubated at 37°C. Solid agar media contained 1.8% (wt/vol) agar. When required, ampicillin and kanamycin were supplemented at 100 μg ml−1 and chloramphenicol and tetracycline at 12.5 μg ml−1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Source/description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80 ΔlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYAargF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoA supE44λ−thi1 gyrA96 relA1 | 51 |

| S17-1 λpir | λpir (recA thi pro hsdR [res− mod+][RP4::2-Tcr::Mu-Kmr::Tn7] λpir phage lysogen) | 47 |

| Genehogs | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZ ΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Smr) endA1 nupG fhuA::IS2 (confers phage T1 resistance) | Invitrogen |

| Y. enterocolitica strains | ||

| 13169 | Serogroup O:3; biogroup 4; recovered from pig | 38, 39 |

| 29854 | Serogroup O:5; biogroup 1A; recovered from food | 29, 30, 39 |

| 83/88 | Serogroup O:5,27; biogroup 3; recovered from food | 30, 31 |

| 966/89 | Serogroup O:5,27; biogroup 2; recovered from human | 29 |

| 31080 | Serogroup O:9; biogroup 2; recovered from pig | This work |

| 12 | Serogroup O:13,7; biogroup 1A; recovered from water | This work |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis 1340 | Serogroup I; recovered from animal | P. Dersch |

| Other strains | ||

| Citrobacter freundii CB1614 | Reference strain BfR | 49 |

| Escherichia hermanii 4560 | Reference strain BfR | This work |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium type I | Reference strain BfR | 49 |

| Shigella flexneri 6:88 Boyd | Reference strain BfR | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pYE854 | 95 kb; isolated from Y. enterocolitica strain 29854 | This work |

| pYE854 I1/01 | pYE854 (Kmr insertion at position 47050) | This work |

| pYE966 | 70 kb; isolated from Y. enterocolitica strain 966/89 | This work |

| p1340 | pYV (Cmr) of Y. pseudotuberculosis strain 1340 | P. Dersch |

| pBR327 | 3.3-kb derivative of pBR322; Apr Tcr | 12 |

| pBR329 | 4.2-kb derivative of pBR322; Apr Tcr Cmr | 11 |

| pIV2 | Yersinia cloning vector; Kmr | 49 |

| pLitmus38 | Cloning vector; Apr | New England Biolabs |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector; Apr | New England Biolabs |

| pUTKm | 7.1-kb R6K-derived suicide vector; Apr Kmr | 13, 28 |

| pUB110 | 4.5-kb Bacillus/Staphylococcus vector; Kmr | 36 |

| mini-Tn5 Cm | R6K-derived suicide vector; Cmr | 13 |

| pJH808 | pIV2 ClaI Ω(pYE854 [3,927 bp, ClaI]) | This work |

| pJH907 | pIV2 HindIII Ω(pYE854 [4,264 bp, HindIII]) | This work |

| pJH907-A | pIV2 Δ(HindIII-EcoRI) Ω(pYE854 [2,404 bp, HindIII-EcoRI]) | This work |

| pJH907-B | pIV2 Δ(HindIII-EcoRI) Ω(pYE854 [1,860 bp, HindIII-EcoRI]) | This work |

| pJH907-C | pIV2 Δ(HindIII-EcoRI) Ω(pYE854 [1,016 bp, HindIII-EcoRI]) | This work |

| pJH907-D | pIV2 Δ(HindIII-EcoRI) Ω(pYE854 [666 bp, HindIII-EcoRI]) | This work |

| pJH907-E | pIV2 Δ(HindIII-EcoRI) Ω(pYE854 [659 bp, HindIII-EcoRI]) | This work |

| pJH907-F | pIV2 Δ(HindIII-EcoRI) Ω(pYE854 [309 bp, HindIII-EcoRI]) | This work |

| pJH907-G | pIV2 Δ(HindIII-EcoRI) Ω(pYE854 [272 bp, HindIII-EcoRI]) | This work |

| pJH1010 | pYE854 PstI (41056-91245::Tcr) | This work |

| pJH1011 | pYE854 BsePI (68129-95275::Tcr) | This work |

| pJH1012 | pYE854 PmeI/SmaI (75368-94503::Tcr) | This work |

| pJH1013 | pYE854 PmeI/StuI (75368-86673::Tcr) | This work |

| pJH1014 | pYE854 EcoRI (75988-85351::Tcr) | This work |

| pJH1015 | pYE854 NdeI (76227-84577::Tcr) | This work |

Conjugation and mobilization experiments.

Matings in which Yersinia strains were used as donor or recipient were carried out at 28°C. All other mating experiments were conducted at 37°C. Strains were grown in LB broth to an A600 of 0.3. A 500-μl amount of the donor bacteria was mixed with 4.5 ml of the recipient. The bacteria were sedimented at 5,000 × g for 5 min, resuspended in 100 μl LB broth, and streaked on a Millipore filter (pore size, 0.45 μm; diameter, 25 mm) placed on an LB agar plate (8). The filters were incubated for 12 h at 28°C or 37°C. Thereafter, cells were suspended in 1 ml 0.7% saline solution and 100-μl aliquots of serial dilutions were plated on selective agar containing the appropriate antibiotics. Transfer frequencies were calculated by the ratio of transconjugants per donor cell.

In vivo mutagenesis of the conjugative plasmids.

Plasmids containing either a kanamycin (Kmr) or a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (Cmr) resistance gene were created by in vivo transposon mutagenesis of the host strains using the mini-Tn5 transposon derivative pUT described by de Lorenzo et al. (13) and Herrero et al. (28). Y. enterocolitica strains harboring plasmid pYE854 or pYE966 were used as recipients for filter mating experiments with E. coli strain S17-1 λpir containing pUTKm or mini-Tn5 Cm (Table 1). Transconjugants were selected on CIN agar (45) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic. To detect plasmids in which the resistance gene had been inserted, plasmid DNA was isolated from the mutants and subjected to restriction analysis and hybridization with the transposon delivery vectors. The insertion sites of the resistance genes were determined by cloning DraI restriction fragments of the pYE854 mutants with the help of the vector pLitmus38 (Apr; New England Biolabs). Sequencing was performed using primers deduced from the marker genes.

Nucleotide sequence determination and analysis of plasmid pYE854.

For shotgun sequencing of pYE854, a fragment library was constructed. Small (1.8-to 2.2-kb) DNA fragments of the plasmid were generated by ultrasonic treatment. After end repair with T4 polymerase (Roche), 10 μg DNA was loaded onto an agarose gel (0.9%). DNA fragments of the appropriate size were excised from the gel. The extracted DNA was cloned into the vector pUC19 cleaved with SmaI (Roche).

DNA sequencing reactions were set up using an Applied Biosystems BigDye Terminator version 3.1 cycle sequencing kit. We have sequenced the shotgun clones from both sides up to a sixfold genome coverage using an ABI 3730 XL sequencer. The data assembly was accomplished by using Staden Package software version 4.6 (Roger Staden, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Gap closure was performed by combinatorial PCR and sequencing of the generated PCR fragments. Sequence analyses were performed by using the MacVector 8.0 software of the Oxford Molecular Group. Blast searches were carried out with the NCBI database, and the GAP program of the GCG package (14) was used for calculating similarity and identity values.

To determine putative promoters, the 300-bp upstream regions of pYE854 open reading frames (ORFs) were analyzed for the existence of −35 and −10 consensus sequences (TTGACA-N15-20-TATAAT) described by Hawley and McClure (27) and Harley and Reynolds (26). To identify the origin of transfer (oriT) of pYE854, the complete nucleotide sequence was analyzed for the existence of consensus sequences for the oriT nic region families described by Zechner et al. (52).

Construction of replicative miniplasmid derivatives of pYE854.

For all DNA manipulations, standard techniques were applied (44). To identify regions essential for plasmid replication, miniplasmid derivatives of pYE854 were created by cleavage of the plasmid DNA with various restriction endonucleases. Restriction fragments bearing overhanging ends were trimmed with T4 polymerase (New England Biolabs). The tetracycline resistance gene (tetA) of Tn5 was amplified by PCR using plasmid pBR327 as template and was ligated to the restriction fragments of pYE854.

Cloning of restriction fragments and of the oriT region of plasmid pYE854.

Covalently closed circular plasmid DNA purified by cesium chloride gradient centrifugation (44) was digested with the restriction endonucleases ClaI and HindIII. The fragments were inserted into the corresponding sites of pIV2 (Kmr) (49). The constructs were introduced into the E. coli strain Genehogs. Recombinant plasmids were characterized by restriction analysis and sequencing. Plasmids containing ClaI restriction fragments resulted in the pJH800 series, and those harboring HindIII restriction fragments gave the pJH900 series (see Fig. 4).

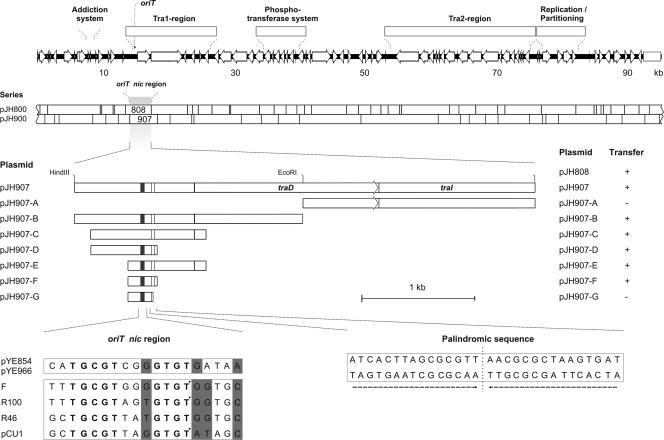

FIG. 4.

Isolation of the pYE854 oriT region. The upper panel shows the linear gene map of pYE854 and a restriction fragment library (pJH800 series ClaI fragments and pJH900 series HindIII fragments) used to identify the oriT sequences present on pJH808 and pJH907. In the middle, the 4.2-kb HindIII restriction fragment of pJH907, which was further reduced in size, is depicted. The smallest DNA fragment conferring mobilization has a size of 309 bp (pJH907-F). +, transfer occurred; −, transfer did not occur. The lower panel illustrates an alignment of the oriT sequences of pYE854 and some other, related plasmids. A shaded background marks positions where two different types of nucleotides may occur. Nucleotides conserved within the oriT nic regions are depicted in bold letters. In cases where the cleavage site has been determined, it is indicated by an arrowhead. On the right, the sequence of the flanking palindrome, which is also essential for conjugation, is shown.

One of the recombinant plasmids described above, pJH907, was shown to be mobilizable by plasmid pYE854. To identify the oriT sequence on pJH907, its 4.2-kb HindIII insert was digested with EcoRI, yielding two restriction fragments that were cloned by use of the vector pIV2, resulting in the plasmids pJH907-A and pJH907-B. oriT located on plasmid pJH907-B was defined by constructing smaller PCR fragments using forward primers containing a HindIII site and reverse primers containing an EcoRI site, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The PCR products were digested with the corresponding restriction endonucleases and inserted into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pIV2. E. coli DH5α transformants containing one of the resulting plasmids, pJH907-C to -G, and either pYE854 or pYE966 were investigated in terms of mobilization of the constructs by the conjugative plasmids (see below).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete sequence of plasmid pYE854 has been submitted to the EMBL databank under the accession number AM905950.

RESULTS

The self-transmissible plasmid pYE854 is able to mobilize pYV.

Plasmid pYE854 was detected in nonpathogenic Y. enterocolitica biogroup 1A strain 29854 recovered from food (Table 1). Strain 29854 also contains the 46.3-kb linear plasmid prophage PY54 which has already been described in more detail (30, 31). To allow selection for pYE854, its host strain was subjected to in vivo mutagenesis with a kanamycin resistance gene (see Materials and Methods). Mutants containing the marker gene on pYE854 were detected by DNA hybridization and analyzed to determine the insertion site (Table 2). In addition, the conjugative properties of the mutants were studied. For filter mating experiments, mutant I1/01 was chosen as the donor in which the resistance gene had inserted within an intergenic region (plasmid position 47050), retaining high-frequency transmission of the plasmid. Selection of the recipients (Table 1) was achieved by transforming gram-negative strains with the vector pBR327 (Apr Tcr) that is known to be nonmobilizable (12). The Bacillus strains possessed an intrinsic tetracycline resistance. Transconjugants were analyzed with respect to their plasmid content and by typing. We observed the transfer of pYE854-I1/01 into a wide range of Yersinia strains and into some other genera belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae, e.g., Citrobacter, Escherichia, Salmonella, and Shigella, but not into Bacillus species (Table 3). The highest transfer frequencies (10−1 to 10−2/donor) were obtained when Yersinia strains were used as donor and recipient, while the efficiencies of conjugation into other genera were determined to be several orders of magnitude lower (Table 4). We studied the stability of pYE854-I1/01 in E. coli for approximately 100 generations under nonselective conditions and could not detect any significant loss of the plasmid. Thus, pYE854 replication is not restricted to Yersinia. Furthermore, plasmid analyses of the transconjugants disclosed that the conjugative plasmid is compatible with the Yersinia virulence plasmid pYV (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Characterization of pYE854 mutants

| Mutant | Position/insertion | ORF(s)a | Related protein(s) and source | Conjugation/mobilizationd of pYV1340 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1/01 | 1157 | 001 | Transposase (Y. pestis KIM) | + |

| A1/02 | 3261 | − | + | |

| A1/03 | 3872 | 007 | None found | + |

| P2/01 | 6288 | 011c | Hypothetical protein (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | + |

| P2/02 | 6413 | 011c | Hypothetical protein (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | + |

| M2/01 | 13644 | 025 | None found | + |

| M2/02 | 19235 | 036 | TraI; conjugative transfer relaxase/helicase (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| M2/03 | 19404 | 036 | TraI; conjugative transfer relaxase/helicase (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| S1/01 | 18341 | 036c | TraI; conjugative transfer relaxase/helicase (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| S1/02 | 18996 | 036 | TraI; conjugative transfer relaxase/helicase (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| E1/01 | 21567 | 036c | TraI; conjugative transfer relaxase/helicase (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| E1/02 | 20783 | 036 | TraI; conjugative transfer relaxase/helicase (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| E1/03 | 20030 | 036 | TraI; conjugative transfer relaxase/helicase (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| B1/01 | 40209 | 094 | Transposase (Y. pestis strain 91001) | + |

| B1/02 | 43850 | 100 | Transposase (E. coli plasmid F) | + |

| B1/03 | 44301 | 100c | Transposase (E. coli plasmid F) | + |

| I1/01 | 47050 | − | + | |

| K3/01 | 49860 | 121 | Hypothetical protein (Y. pseudotuberculosis IP 31758) | + |

| T1/01 | 50299 | 122 | Permease (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | − |

| T1/02 | 50685 | 122 | Permease (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | − |

| R1/01 | 52439 | 127 | Hypothetical protein (Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1) | + |

| G2/01 | 55264 | 142c | DNA transfer and F pilus assembly protein (Sphingomonas sp. SKA58) | − |

| D1/01 | 59112 | 144 | TraH; conjugative transfer protein precursor (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| D1/02 | 60919 | 147 | Putative lipoprotein (Porphyromonas gingivalis W83) | − |

| O1/01 | 63138 | 156c | TraU; conjugative transfer protein precursor (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| H1/01 | 65749 | 162 | TraZ; conjugative transfer protein (S. flexneri plasmid R100) | − |

| H1/02 | 66001 | 164 | TraN; type IV conjugative transfer system protein (Yersinia ruckeri) | +b |

| H1/03 | 66255 | 164 | TraN; type IV conjugative transfer system protein (Y. ruckeri) | +b |

| G1/01 | 72004 | 171 | TraB; conjugative transfer protein (E. coli plasmid F) | − |

| R2/01 | 76626 | 183 | GpA; phage terminase (Shewanella denitrificans OS217) | + |

| C1/01 | 84818 | 203 | None found | + |

| C1/02 | 86989 | 209 | Transposase (Y. pestis strain 91001) | + |

| C1/03 | 88157 | 211; 212 | Transposase (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); prophage integrase (partial) (Erwinia carotovora sp. atroseptica SCRI1043) | + |

| P1/01 | 90939 | 219c | Cation efflux protein (Dechloromonas aromatica RCB) | + |

| A1/04 | 93076 | 224c | Transposase (Proteus vulgaris) | + |

A dash indicates that insertion occurred within an intergenic sequence.

Transferred with reduced frequencies.

Several ORFs are affected. See Table S2 in the supplemental material.

+, conjugation/mobilization occurred; −, conjugation/mobilization did not occur.

TABLE 3.

Results of the mating experiments with various recipient strains

| Recipient species, serogroup, or type | No. of strains tested | No. of strains in which transfer of pYE854 occurreda |

|---|---|---|

| Y. enterocolitica serogroups | 25 | 24/25 |

| O:3 | 7 | 7/7 |

| O:5 | 5 | 4/5 |

| O:5,27 | 4 | 4/4 |

| O:7,8 | 1 | 1/1 |

| O:8 | 4 | 4/4 |

| O:9 | 4 | 4/4 |

| Other Yersinia spp. | ||

| Y. pseudotuberculosis | 2 | 2/2 |

| Y. intermedia | 2 | 2/2 |

| Y. frederiksenii | 2 | 2/2 |

| Y. kristensenii | 2 | 2/2 |

| Y. mollaretii | 2 | 1/2 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | 1 | 0/1 |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | 1 | 0/1 |

| Bacillus spp. | 8 | 0/8 |

| B. subtilis | 2 | 0/2 |

| B. licheniformis | 2 | 0/2 |

| B. megaterium | 2 | 0/2 |

| B. thuringiensis | 2 | 0/2 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 1 | 1/1 |

| Escherichia spp. | 5 | 5/5 |

| E. coli | 4 | 4/4 |

| E. hermanii | 1 | 1/1 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 | 0/1 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 | 0/1 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 2 | 0/2 |

| P. aeruginosa | 1 | 0/1 |

| P. putida | 1 | 0/1 |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | 2 | 2/2 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium type I | 1 | 1/1 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium type III | 1 | 1/1 |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 | 0/1 |

| Shigella flexneri | 1 | 1/1 |

The donor strain for all mating experiments was Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27).

TABLE 4.

Efficiencies of pYE854 and pYE966 conjugation and pYV mobilization

| Donor (serogroup) | Recipient (serogroup) | Conjugative plasmid | Transfer rate | Mobilization of pYV1340a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | Y. enterocolitica 12 (O:13,7) | pYE854 | 1.2 × 10−1 | 1.2 × 10−2 |

| Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | Y. enterocolitica 12 (O:13,7) | pYE966 | 9.4 × 100 | 9.6 × 10−1 |

| Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | E. coli K12 DH5α | pYE854 | 6.3 × 10−5 | 2.3 × 10−7 |

| Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | E. coli K12 DH5α | pYE966 | 3.2 × 10−5 | 9.7 × 10−6 |

| Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | S. flexneri 6:88 Boyd | pYE854 | 2.3 × 10−7 | 7.4 × 10−8 |

| Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | Escherichia hermanii 4560 | pYE854 | 7.7 × 10−7 | − |

| Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | Citrobacter freundii CB1614 | pYE854 | 1.6 × 10−8 | − |

| Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium type I | pYE854 | 9.5 × 10−7 | − |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis (I) | Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (O:5,27) | pYE854 | 1.1 × 10−2 | 1.1 × 10−5 |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis (I) | Y. enterocolitica 12 (O:13,7) | pYE854 | 1.1 × 10−6 | 1.7 × 10−8 |

A dash indicates that no mobilization was detectable.

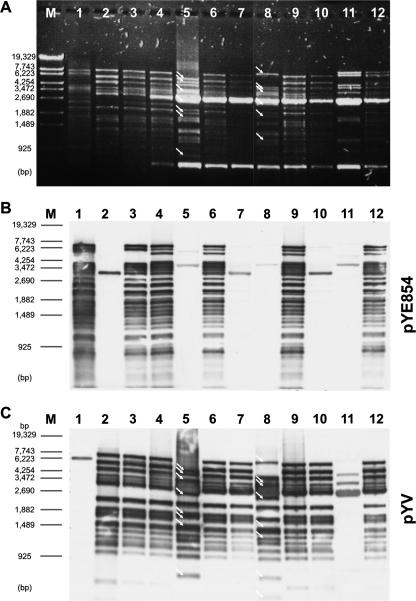

FIG. 1.

Plasmid analysis of donor strains, recipients, and transconjugants. All donor and recipient strains contained the plasmids pYE854/pYV and pBR327, respectively. (A) An 0.8% agarose gel showing DraI restriction patterns of the plasmids. Lane M, marker (λ Eco130I); lane 1, pYE854; lane 2, pYV (p1340); lane 3, Y. pseudotuberculosis 1340 (donor); lane 4, E. coli DH5α (donor); lane 5, Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (recipient); lane 6, Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (transconjugant, donor strain was Y. pseudotuberculosis 1340); lane 7, Y. enterocolitica 83/88 (transconjugant, donor strain was E. coli DH5α), lane 8, Y. enterocolitica 31080 (recipient); lane 9, Y. enterocolitica 31080 (transconjugant, donor strain was Y. pseudotuberculosis 1340); lane 10, Y. enterocolitica 31080 (transconjugant, donor strain was E. coli DH5α); lane 11, Y. enterocolitica 12 (recipient); lane 12, Y. enterocolitica 12 (transconjugant, donor strain was Y. pseudotuberculosis 1340). (B) Southern hybridization of the plasmids shown in panel A to pYE854. Transconjugants obtained by using E. coli as donor were selected on agar containing chloramphenicol (pYV) and tetracycline (pBR327) and did not harbor pYE854 (lanes 7 and 10). (C) Southern hybridization of the plasmids shown in panel A to pYV (p1340). Arrows indicate restriction fragments that are different in the virulence plasmids of the recipients and the transconjugants.

Up to now, it has not been elucidated whether pYV can be mobilized with the help of another plasmid naturally occurring in this genus. To answer this question, plasmid pYE854-I1/01 was introduced into Yersinia pseudotuberculosis strain 1340 (Table 1), whose virulence plasmid (p1340) is marked with a cat gene inserted adjacent to yadA. Following this step, the resulting strain containing both plasmids was used as a donor strain in mating experiments with various recipients harboring pBR327. Triply resistant transconjugants containing the plasmids pYE854-I1/01, p1340, and pBR327 could be isolated from all tested pathogenic Yersinia strains, from nonpathogenic Y. enterocolitica biogroup 1A strain 12, from E. coli K12, and from a Shigella flexneri strain. Mobilization of p1340 by pYE854-I1/01 occurred with frequencies between 10−2 to 10−8 per donor cell (Table 4). Southern analysis of plasmids isolated from transconjugants disclosed that, in pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains, the indigenous virulence plasmid was replaced by the newly acquired pYV of Y. pseudotuberculosis, discernible by the different restriction patterns of the plasmids (Fig. 1A and C, lanes 5, 6, 8, and 9). DNA hybridization also revealed weak homology between pYE854-I1/01 and p1340 (Fig. 1B, lane 2). It cannot be ruled out that, especially in cases of low transfer frequency, a cointegrate between pYE854 and pYV was formed. However, cointegrate formation has never been observed in the donor strain or any of the analyzed transconjugants. For the mating experiments, we also used as donor an E. coli K12 strain in which plasmid p1340 had been introduced by electroporation and pYE854-I1/01 by subsequent conjugation. Even from E. coli K12, plasmid p1340 was transmitted to pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains (Fig. 1A and C, lanes 7 and 10), albeit with reduced frequencies (Table 4). Similarly to p1340, pYV of the Y. enterocolitica serogroup O:3 strain 13169 (Table 1) was transmitted, a result that documents that the virulence plasmids of both Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis can be transferred with the help of pYE854.

Overall sequence analysis of pYE854.

The complete nucleotide sequence (95,499 bp) of pYE854 has been determined. The plasmid has an average G+C content of 42.3%, slightly lower than the 48.5% ± 1.5% (mean ± standard deviation) reported for the host Y. enterocolitica (5). However, the G+C contents of different ORFs vary in the range from 28% to 60%. The bioinformatic analysis revealed 232 ORFs with potential coding capacity (minimum protein size, 50 amino acids) and an ATG start codon (see Table S2 in the supplemental material for details). Both DNA strands of the plasmid contain an equal number of ORFs. The database search gave matches for 80 deduced gene products with identities to other protein sequences of between 27% and 100% (Table 5). We did not detect genes obviously encoding known virulence factors or genes conferring antibiotic resistance. The strongest overall similarities found were to transfer proteins of Yersinia bercovieri and the F plasmid, but significant homologies also exist to proteins belonging to a phosphotransferase system (PTS) of Vibrio vulnificus.

TABLE 5.

Selected ORFs of plasmid pYE854

| ORF | Start position | Stop position | Length (amino acids) | Molmass (kDa) | pI | Predicted function | Related protein(s) and source/description | E value | Extent of best match % identity/length of region (no. of amino acids) | NCBI accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | 366 | 1388 | 340 | 37.83 | 9.97 | Transposase | Transposase (Y. pestis KIM) | 0.0 | 95/340 | AAC82723.1 |

| 003 | 1803 | 1489 | 104 | 11.63 | 9.80 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein YPA_MT0073 (Y. pestis Antiqua) | 3.0E-06 | 84/26 | YP_636761.1 |

| 004 | 1926 | 2243 | 105 | 12.10 | 9.90 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein YR71pYR1_0023 (Yersinia ruckeri) | 3.0E-15 | 47/97 | YP_001101717.1 |

| 006 | 3096 | 2431 | 221 | 26.04 | 7.13 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein AmetDRAFT_2972 (Alkaliphilus metalliredigenes QYMF) | 2.0E-31 | 37/213 | ZP_00799958.1 |

| 008 | 4048 | 5493 | 481 | 54.15 | 8.67 | Methylase | Site-specific DNA methylase (Y. pestis biovar Orientalis strain IP275) | 7.0E-116 | 45/470 | ZP_01175891.1 |

| 010 | 5616 | 5993 | 125 | 14.16 | 7.13 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein pCTX-M3_039 (Citrobacter freundii) | 1.0E-15 | 39/112 | NP_774998.1 |

| 011 | 6105 | 7598 | 497 | 56.27 | 7.95 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein YberA_01003565 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); putative DNA primase (Clostridium difficile 630) | 2.0E-157; 5.0E-12 | 98/306; 23/394 | ZP_00820298.1; YP_001087592.1 |

| 013 | 6562 | 6401 | 53 | 5.57 | 6.21 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein Cphamn1DRAFT_2669 (Chlorobium phaeobacteroides BS1) | 1.2E-02 | 50/46 | ZP_00531443.1 |

| 015 | 7761 | 8093 | 110 | 12.47 | 9.61 | Addiction system (toxin) | Hypothetical protein Plu0205 (Photorhabdus luminescens sp. laumondii TTO1); Gp49 (E. coli bacteriophage N15); Gp49 (Klebsiella oxytoca bacteriophage φKO2) | 1.0E-32; 2.0E-12; 6.0E-12 | 82/101; 40/103; 40/103 | NP_927569.1; NP_046945.1; YP_006629.1 |

| 016 | 8086 | 8388 | 100 | 11.08 | 7.15 | Addiction system (antitoxin) | Predicted transcriptional regulator (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); Gp48 (E. coli bacteriophage N15); Gp48 (Klebsiella oxytoca bacteriophage φKO2) | 4.0E-41; 1.0E-04; 2.0E-03 | 95/100; 32/83; 29/87 | ZP_00820297.1; NP_046944.1; YP_006628.1 |

| 018 | 8863 | 9264 | 133 | 15.30 | 4.85 | Dehydrogenase | Uncharacterized anaerobic dehydrogenase (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 5.0E-46 | 89/110 | ZP_00820229.1 |

| 019 | 9300 | 10109 | 269 | 31.24 | 5.08 | Hydratase | Putative aconitate hydratase (Geobacter lovleyi SZ) | 1.6E-02 | 37/67 | ZP_01594594.1 |

| 021 | 10829 | 11230 | 133 | 15.30 | 4.85 | Dehydrogenase | Uncharacterized anaerobic dehydrogenase (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 5.0E-46 | 89/110 | ZP_00820229.1 |

| 022 | 11266 | 12075 | 269 | 31.24 | 5.08 | Hydratase | Putative aconitate hydratase (Geobacter lovleyi SZ) | 1.6E-02 | 37/67 | ZP_01594594.1 |

| 024 | 13055 | 13357 | 100 | 11.67 | 8.89 | Unknown | Conserved hypothetical protein (E. coli) | 1.0E-06 | 37/67 | ABF67878.1 |

| 030 | 15280 | 17352 | 690 | 77.22 | 8.23 | DNA transport | TraD (Legionella pneumophila subsp. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1); type IV secretory pathway, VirD4 component (Vibrio vulnificus CMCP6); coupling protein TraD (E. coli plasmid F) | 2.0E-74; 5.0E-62; 8.0E-61 | 31/570; 27/597; 26/682 | YP_096091.1; NP_762611.1; NP_061481.1 |

| 036 | 17353 | 22323 | 1656 | 186.80 | 8.47 | oriT relaxase/helicase | Mobilization protein TraI (E. coli); TraI (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium plasmid R46); conjugative transfer relaxase/helicase (Shigella flexneri plasmid R100) | 1.0E-90; 2.0E-90; 4.0E-43 | 31/956; 31/956; 37/318 | AF109305_3; NP_511201.1; NP_052981.1 |

| 040 | 22895 | 22368 | 175 | 19.72 | 9.83 | Restriction endonuclease | Hypothetical protein pEL60p14 (Erwinia amylovora); hypothetical protein R46_003 (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium plasmid R46); Restriction endonuclease (Serratia proteamaculans 568) | 2.0E-32; 1.0E-31; 2.0E-30 | 49/139; 44/156; 45/140 | NP_943213.1; NP_511181.1; ZP_01535230.1 |

| 043 | 24200 | 23568 | 210 | 23.40 | 9.62 | Transglycosylase | Putative transglycosylase PilT (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium plasmid R46); putative twitching motility protein PilT (Sodalis glossinidius strain morsitans); lytic transglycosylase (E. coli plasmid F) | 2.0E-21; 5.0E-21; 3.0E-13 | 40/132; 42/163; 36/155 | BAA77980.1; YP_456185.1; NP_061449.1 |

| 045 | 24758 | 25174 | 138 | 15.83 | 9.12 | Transcription regulation | Histone-like nucleoid-structuring protein H-NS (Shewanella putrefaciens 200); DNA-binding protein H-NS (Marinomonas sp. MED121) | 6.0E-04; 7.0E-03 | 27/118; 27/101 | ZP_01704518.1; ZP_01076238.1 |

| 049 | 26280 | 25510 | 256 | 28.67 | 9.87 | Integrase | Hypothetical protein YpseI_02003938 (Y. pseudotuberculosis IP 31758); integrase COG0582 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); site-specific recombinase Int (E. coli plasmid F) | 3.0E-140; 2.0E-137; 1.0E-45 | 99/256; 97/256; 46/246 | ZP_01494755.1; ZP_00821919.1; NP_061423.1 |

| 055 | 27837 | 27067 | 256 | 28.55 | 5.52 | Transporter | Hypothetical protein AGR_pAT_528 (Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58); autotransporter protein (Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58); type IV secretory pathway, adhesin AidA (Burkholderia cenocepacia PC184) | 5.0E-21; 9,0E-21; 7.0E-15 | 27/262; 27/262; 27/251 | NP_396297.1; NP_535736.1; ZP_00978381.1 |

| 059 | 29753 | 27822 | 643 | 66.20 | 4.60 | Unknown | Filamentous hemagglutinin, adhesin HecA repeat ×2 (Ralstonia eutropha JMP134); serine protease EspC precursor (enteropathogenic E. coli-secreted protein C) | 3.0E-03; 4.0E-03 | 23/451; 28/240 | YP_294319.1; ESPC_ECO27 |

| 062 | 32162 | 29763 | 799 | 87.93 | 8.73 | Hyaluronate lyase | Hypothetical protein VV0534 (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016); hypothetical protein VV0533 (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016); hyaluronate lyase precursor (Vibrio fischeri ES114) | 7.0E-146; 4.0E-123; 3.0E-116 | 39/813; 34/781; 34/769 | NP_933327.1; NP_933326.1; YP_206952.1 |

| 066 | 33185 | 32181 | 334 | 39.39 | 9.05 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein VV0535 (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016) | 9.0E-38 | 33/339 | NP_933328.1 |

| 070 | 34696 | 33230 | 488 | 56.39 | 7.51 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein PCNPT3_11983 (Psychromonas sp. CNPT3); hypothetical protein VV0544 (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016) | 4.0E-131; 3.0E-119 | 46/493; 44/492 | ZP_01217030.1; NP_933337.1 |

| 073 | 35755 | 34721 | 344 | 39.97 | 5.21 | Glucuronyl hydrolase | Hypothetical protein VV0541 (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016); hypothetical protein PCNPT3_11988 (Psychromonas sp. CNPT3); predicted unsaturated glucuronyl hydrolase (Y. pestis Angola) | 2.0E-111; 6.0E-108; 5.0E-107 | 58/334; 53/341; 55/341 | NP_933334.1; ZP_01217031.1; ZP_00796104.1 |

| 075 | 36272 | 35835 | 145 | 15.52 | 4.11 | PTS | PTS, mannose/fructose-specific component IIA (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016); PTS, N-acetylgalactosamine-specific IIA component (Psychromonas sp. CNPT3) | 2.0E-34; 3.0E-26 | 58/124; 50/124 | NP_933333.1; ZP_01217033.1 |

| 079 | 37151 | 36282 | 289 | 31.45 | 8.16 | PTS | PTS, mannose/fructose/N-acetylgalactosamine-specific component IID (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016); PTS, N-acetylgalactosamine-specific IID component (Psychromonas sp. CNPT3) | 9.0E-103; 2.0E-87 | 61/293; 57/292 | NP_933332.1; ZP_01217034.1 |

| 082 | 37908 | 37138 | 256 | 27.41 | 4.90 | PTS | PTS, mannose/fructose/N-acetylgalactosamine-specific component IIC (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016); PTS, N-acetylgalactosamine-specific IIC component (Psychromonas sp. CNPT3) | 3.0E-82; 6.0E-58 | 63/254; 50/256 | NP_933331.1; ZP_01217035.1 |

| 086 | 38401 | 37928 | 157 | 17.59 | 9.37 | PTS | PTS, mannose/fructose/N-acetylgalactosamine-specific component IIB (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016); PTS, N-acetylgalactosamine-specific IIB component (Psychromonas sp. CNPT3) | 1.0E-43; 3.0E-38 | 55/155; 51/158 | NP_933330.1; ZP_01217036.1 |

| 089 | 39302 | 38514 | 262 | 29.27 | 5.51 | Transcriptional regulator | Transcriptional regulator of sugar metabolism (Vibrio vulnificus YJ016); transcriptional repressor of aga operon (Psychromonas sp. CNPT3) | 2.0E-29; 1.0E-11 | 33/246; 25/243 | NP_933329.1; ZP_01217450.1 |

| 090 | 39492 | 39749 | 85 | 9.64 | 10.03 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein YPA_MT0073 (Y. pestis Antiqua) | 2.0E-06 | 84/26 | YP_636761.1 |

| 094 | 40872 | 39850 | 340 | 37.82 | 9.97 | Transposase | Probable transposase (Y. pestis biovar Microtus strain 91001) | 0.0 | 94/340 | NP_995565.1 |

| 097 | 41237 | 40896 | 113 | 12.57 | 7.02 | ATPase | Hypothetical protein R64_p028 (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium plasmid R64); oxyanion-translocating ATPase (Y. intermedia ATCC 29909); arsenical pump-driving ATPase (Y. enterocolitica 8081) | 6.0E-20; 8.0E-15; 1.0E-14 | 97/48; 78/47; 55/70 | NP_863383.1; ZP_00834873.1; YP_001007632.1 |

| 099 | 41902 | 41246 | 218 | 24.52 | 9.90 | Recombinase | Recombinase (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium plasmid R46); putative resolvase (Y. pestis biovar Microtus strain 91001) | 7.0E-104; 1.0E-85 | 98/218; 81/209 | NP_511241.1; NP_995411.1 |

| 100 | 41982 | 44990 | 1002 | 113.71 | 8.84 | Transposase | Transposase (E. coli plasmid F) | 0.0 | 91/1001 | NP_061389.1 |

| 102 | 42122 | 41964 | 52 | 5.62 | 9.81 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein (E. coli) | 3.0E-02 | 53/39 | ABG49234.1 |

| 111 | 45167 | 46048 | 293 | 33.97 | 6.54 | Restriction endonuclease | ENSANGP00000029959 (Anopheles gambiae strain PEST); restriction endonuclease (E. coli F11) | 2.0E-112; 8.0E-80 | 69/289; 52/281 | XP_001230420.1; ZP_00726032.1 |

| 115 | 46977 | 46144 | 277 | 32.05 | 4.49 | Unknown | W0044 (E. coli) | 3.0E-19 | 29/257 | AF401292_38 |

| 116 | 47513 | 48139 | 208 | 24.42 | 9.24 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein XOO2824 (Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae KACC10331) | 8.0E-08 | 25/151 | YP_201463.1 |

| 121 | 49871 | 49107 | 254 | 29.92 | 5.14 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein YpseI_02003937 (Y. pseudotuberculosis IP 31758) | 2.0E-20 | 35/223 | ZP_01494754.1 |

| 122 | 50121 | 50852 | 243 | 27.43 | 8.95 | Permease | Hypothetical protein YPTB1564 (Y. pseudotuberculosis IP 32953); permease of the major facilitator superfamily (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 2.0E-63; 3.0E-06 | 56/214; 25/182 | YP_070092.1; ZP_00821712.1 |

| 125 | 51098 | 51577 | 159 | 17.44 | 8.27 | Unknown | Hemolysin-coregulated protein (Burkholderia dolosa AUO158) | 3.0E-45 | 56/157 | EAY70565.1 |

| 127 | 51850 | 52896 | 348 | 39.58 | 9.11 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein Amb1131 (Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1) | 1.0E-16 | 31/238 | YP_420494.1 |

| 129 | 53194 | 53445 | 83 | 9.48 | 7.15 | Transcriptional regulator | Transcriptional regulator, XRE family (Serratia proteamaculans 568); putative DNA-binding protein (Y. enterocolitica 8081) | 7.0E-28; 8.0E-24 | 71/82; 63/83 | ZP_01535204.1; YP_001007657.1 |

| 142 | 58491 | 54838 | 1217 | 128.71 | 4.92 | Pilus assembly | Exoprotein involved in heme utilization or adhesion (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); DNA transfer and F pilus assembly protein (Sphingomonas sp. SKA58); pilus assembly protein/mating pair stabilization protein (E. coli plasmid F) | 0.0; 4.0E-54; 2.0E-08 | 99/1217; 28/496; 16/595 | ZP_00821912.1; ZP_01301957.1; NP_061478.1 |

| 144 | 59876 | 58488 | 462 | 51.27 | 5.86 | Pilus assembly | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001910 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); putative pilus assembly protein (Salmonella enterica sp. enterica serovar Typhi strain CT18); conjugative transfer protein TraH precursor (Shigella flexneri plasmid R100) | 0.0; 5.0E-14; 5.0E-11 | 99/412; 33/164; 26/218 | ZP_00821911.1; NP_569448.1; NP_052975.1 |

| 145 | 60749 | 59886 | 287 | 32.57 | 9.05 | Pilus assembly | Thiol-disulfide isomerase and thioredoxins (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); conjugative transfer protein TraF precursor (Shigella flexneri plasmid R100) | 2.0E-114; 1.0E-20 | 100/208; 19/248 | ZP_00821910.1; NP_052969.1 |

| 147 | 61178 | 60759 | 139 | 14.83 | 9.28 | Pilus assembly | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001908 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); putative lipoprotein (Porphyromonas gingivalis W83) | 1.0E-58; | 99/132; 32/122 | ZP_00821909.1; NP_904997.1 |

| 148 | 61653 | 61189 | 154 | 17.58 | 7.35 | Pilus assembly | Type IV secretory pathway, protease TraF (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); TraF protein (plasmid pKJK5) | 6.0E-083.0E-73; 3.0E-14 | 98/137; 20/165 | ZP_00821908.1; YP_709182.1 |

| 150 | 62372 | 61653 | 239 | 26.76 | 8.83 | Pilus assembly | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001906 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); TrbC, sex pilus assembly and mating-pair formation protein (Erythrobacter sp. NAP1); conjugative transfer protein TrbC (Shigella flexneri plasmid R100) | 4.0E-117; 2.0E-06; 4.0E-10 | 96/239; 26/205; 19/222 | ZP_00821907.1; ZP_01039316.1; NP_052965.1 |

| 156 | 63955 | 62372 | 527 | 58.97 | 6.03 | Conjugative transfer | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001905 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); TraU family protein (Pelobacter propionicus DSM 2379); conjugative transfer protein TraU precursor (Shigella flexneri plasmid R100) | 0.0; 2.0E-82; 2e-44 | 99/514; 44/328; 34/312 | ZP_00821906.1; YP_899942.1; NP_052963.1 |

| 157 | 64343 | 64110 | 77 | 8.73 | 4.36 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein pYptb0019 (Y. pseudotuberculosis IP 32953) | 2.0E-03 | 32/76 | YP_068527.1 |

| 162 | 65969 | 64359 | 536 | 57.69 | 4.92 | Conjugative transfer | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001904 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); essential for conjugative transfer protein (Methylibium petroleiphilum PM1); TraZ (Shigella flexneri plasmid R100) | 2.0E-98; 4.0E-24; 1.0E-12 | 95/184; 38/203; 36/119 | ZP_00821905.1; YP_001023391.1; BAA78871.1 |

| 164 | 67995 | 65944 | 683 | 74.84 | 5.26 | Mating-pair stabilization | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001903 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); type IV conjugative transfer system protein TraN (Y. ruckeri) | 0.0; 4.0E-25 | 97/662; 44/149 | ZP_00821904.1; YP_001101789.1 |

| 167 | 70570 | 67997 | 857 | 96.95 | 5.63 | Pilus assembly | Type IV secretory pathway, VirB4 components (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); sex pilus assembly protein (Syntrophus aciditrophicus SB); conjugative transfer protein TraC (Shigella flexneri plasmid R100) | 0.0; 6.0E-142; 4.0E-18 | 94/849; 34/863; 22/767 | ZP_00821903.1; YP_461725.1; NP_052960.1 |

| 168 | 71076 | 70570 | 168 | 18.17 | 8.17 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001901 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 4.0E-79 | 98/168 | ZP_00821902.1 |

| 171 | 72350 | 71100 | 416 | 44.62 | 7.10 | Pilus assembly/conjugative transfer | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001900 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); TraB pilus assembly family protein (Pelobacter propionicus DSM 2379); conjugative transfer protein TraB (E. coli plasmid F) | 3.0E-164; 7.0E-39; 8.0E-10 | 100/308; 30/413; 23/388 | ZP_00821901.1; YP_899948.1; NP_061457.1 |

| 173 | 73135 | 72347 | 262 | 28.68 | 8.62 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein SKA58_02650 (Sphingomonas sp. SKA58) | 2.0E-27 | 33/235 | ZP_01301938.1 |

| 174 | 73787 | 73137 | 216 | 24.52 | 9.12 | Pilus assembly | Hypothetical sex pilus assembly and synthesis protein (Sphingomonas sp. SKA58) | 1.0E-11 | 27/176 | ZP_01301937.1 |

| 175 | 74069 | 73797 | 90 | 10.76 | 8.35 | Unknown | Hypothetical membrane protein (Sphingomonas sp. SKA58) | 2.0E-07 | 29/89 | ZP_01301936.1 |

| 176 | 74454 | 74086 | 122 | 13.03 | 8.97 | Pilus assembly | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001899 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); conjugative transfer protein TraE (Shigella flexneri plasmid R100) | 4.0E-33; 2.0E-04 | 100/76; 19/181 | ZP_00821900.1; NP_052949.1 |

| 179 | 75389 | 74508 | 293 | 32.67 | 7.36 | Isomerase | Protein-disulfide isomerase (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 4.0E-154 | 96/292 | ZP_00821899.1 |

| 183 | 76692 | 76339 | 117 | 13.57 | 9.39 | Terminase | Phage terminase GpA (Shewanella denitrificans OS217) | 2.8E-02 | 32/68 | YP_564251.1 |

| 185 | 76792 | 77067 | 91 | 10.52 | 9.31 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein YberA_01001897 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 1.0E-46 | 100/91 | ZP_00821898.1 |

| 187 | 77277 | 78677 | 466 | 52.42 | 9.68 | Replication | Hypothetical protein pIP404_p03 (plasmid pIP404); replication protein (Clostridium perfringens) | 1.0E-06; 5.0E-06 | 30/153; 31/151 | NP_040453.1; YP_209688.1 |

| 191 | 79519 | 80388 | 289 | 31.93 | 6.33 | Partitioning | ATPase involved in chromosome partitioning (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); IncC1 partitioning protein (plasmid pB3) | 4.0E-160; 9.0E-14 | 99/274; 26/291 | ZP_00821897.1; YP_133955.1 |

| 194 | 80385 | 81776 | 463 | 51.23 | 5.29 | Transcriptional regulator/partitioning | Predicted transcriptional regulator (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970); plasmid replication/partition protein (Listonella anguillarum); KorB partitioning and repressor protein (plasmid QKH54) | 0.0; 8.0E-10; 2.0E-03 | 98/463; 30/182; 28/194 | ZP_00821896.1; AAO92393.1; YP_619804.1 |

| 196 | 81779 | 82516 | 245 | 28.09 | 5.39 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein LV003 (Klebsiella pneumoniae) | 1.0E-05 | 34/89 | NP_943506.1 |

| 202 | 84500 | 84321 | 59 | 7.04 | 4.63 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein RSP_7393 (Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1) | 7.0E-08 | 57/54 | YP_345433.1 |

| 205 | 85265 | 85888 | 207 | 23.36 | 5.39 | Unknown | Hypothetical protein YberA_01003603 (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 2.0E-76 | 98/142 | ZP_00820260.1 |

| 207 | 85889 | 86638 | 249 | 27.85 | 9.47 | Adenylosuccinate synthase | Adenylosuccinate synthase (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 7.0E-111 | 90/211 | ZP_00820259.1 |

| 209 | 87761 | 86739 | 340 | 37.83 | 9.97 | Transposase | Probable transposase (Y. pestis biovar Microtus strain 91001) | 0.0 | 95/340 | NP_995565.1 |

| 211 | 88141 | 89379 | 412 | 47.55 | 9.71 | Transposase | Transposase and inactivated derivatives (Y. bercovieri ATCC 43970) | 0.0 | 96/412 | ZP_00820226.1 |

| 212 | 88254 | 87976 | 92 | 10.71 | 9.55 | Integrase | Prophage integrase (Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica SCRI1043) | 5.0E-06 | 40/85 | YP_050272.1 |

| 217 | 89817 | 90428 | 203 | 23.06 | 7.48 | Unknown | Putative membrane protein (Bordetella avium 197N) | 2.0E-23 | 33/179 | CAJ49184.1 |

| 219 | 90628 | 91551 | 307 | 33.54 | 5.66 | Transporter | Cation efflux protein (Dechloromonas aromatica RCB); predicted Co/Zn/Cd cation transporter (Nostoc punctiforme PCC 73102) | 1.0E-115; 2.0E-79 | 70/300; 57/295 | YP_284269.1; ZP_00110704.1 |

| 223 | 92449 | 91808 | 213 | 24.83 | 9.39 | Recombinase | Resolvase, N-terminal (Shewanella baltica OS155); site-specific recombinase, DNA invertase Pin homolog (E. coli B7A) | 6.0E-98; 3.0E-87 | 95/210; 94/191 | ZP_00580490.1; ZP_00714543.1 |

| 224 | 92617 | 342 | 1074 | 121.49 | 9.47 | Transposase | Transposase (Proteus vulgaris) | 0.0 | 89/1055 | NP_639975.1 |

Two DNA regions encoding transfer proteins are essential for conjugation.

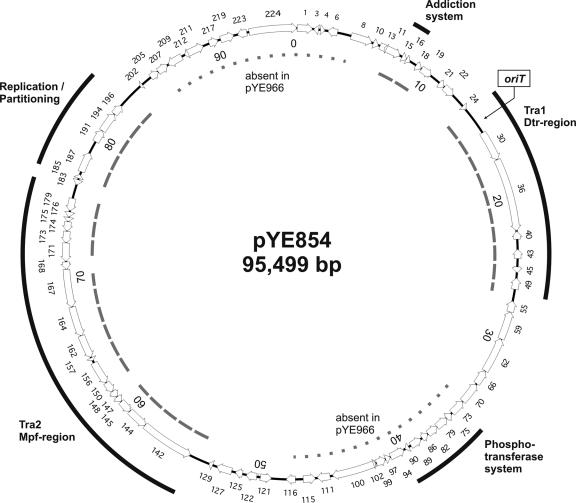

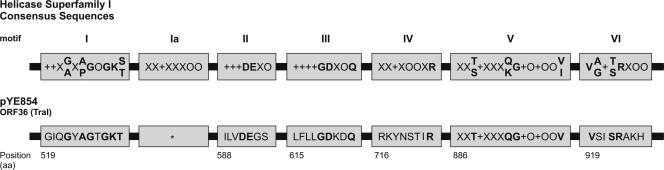

The genetic map of pYE854 shows two regions (Tra1 and Tra2) which probably encode a conjugative transfer system. Similar to IncP plasmids, e.g., RP4 and R751, the Tra regions of pYE854 are separated (Fig. 2). The analysis of the Tra1 region revealed two products (ORF 30 and ORF 36) which are presumably involved in DNA transfer replication and coupling. The putative coupling protein (ORF 30) is related to the TraD of the F factor, which belongs to the TraG family of coupling proteins. It contains motifs that are important for DNA transfer (46). The ORF 36 product might code for a major component of the pYE854 relaxosome. This protein contains sequence motifs that are characteristic for known relaxases and TraI helicases, showing that it belongs to superfamily 1 of the helicases (Fig. 3) (25). Relaxases initiate and terminate conjugation by catalyzing site- and strand-specific cleavage and rejoining reactions at the plasmid-encoded nic site (oriT). The origin of transfer is typically located next to the DNA processing genes. Approximately 500 bp upstream of ORF 30, we identified a sequence motif similar to the oriT nic region of the F factor (Fig. 4). For functional analyses, a 4.2-kb HindIII restriction fragment containing this motif was inserted into the nonmobilizable vector pIV2 (see Materials and Methods). The recombinant plasmid pJH907 was mobilized by pYE854 with frequencies of up to 10−3 per donor, whereas other HindIII restriction fragments of a pYE854 library did not mediate mobilization. By stepwise reduction of the 4.2-kb fragment, the functional oriT core region was narrowed down to 309 bp (Fig. 4). Adjacent to the oriT sequence lies a 30-bp palindrome. Partial removal of the palindrome resulted in a loss of mobilization, demonstrating that the repeat is also essential for plasmid transmission. To exclude the presence of other oriT sequences on pYE854 that might have been inactivated by HindIII cleavage, a ClaI restriction fragment library was examined in terms of mobilization. Only the 3.9-kb restriction fragment of plasmid pJH808 overlapping with the 4.2-kb HindIII fragment of pJH907 conferred mobilization of the vector pIV2 (Fig. 4). Hence, pYE854 harbors a single origin of transfer located within the Tra1 region. Since the oriT sequence is located on the minus strand of pYE854, DNA transfer is initiated at the left end of the Tra1 region and ends with the transmission of the Tra1 genes.

FIG. 2.

Genetic map of pYE854. Black bars indicate DNA regions involved in plasmid transmission, replication, and maintenance, as well as genes that might belong to a PTS. The position of the oriT is marked by an arrowhead. DNA segments that have been identified and those that are missing in pYE966 are indicated by dashed lines and dotted lines, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Helicase motifs identified within TraI of pYE854 (according to Hall and Matson [25]). *, for the consensus sequence Ia, several possible motifs have been identified (data not shown). The position of the first amino acid residue of each motif of pYE854 is given. aa, amino acids. Amino acid residues identical in motifs of TraI of pYE854 and other helicases are indicated by bold letters. + and O represent a hydrophobic and a hydrophilic residue, respectively. Residues not restricted to being hydrophobic and hydrophilic are represented by an X.

Besides the aforementioned products, the Tra1 region might code for additional proteins crucial for conjugation. Possible candidates are the products of ORFs 40, 43, and 45, which are similar to a restriction endonuclease, a lytic transglycosylase, and a DNA-binding protein, respectively, though it remains open which role these proteins might play in DNA transfer.

The Tra2 region is approximately 20 kb in length and contains 17 ORFs whose products show homologies to known proteins (Fig. 2). Eleven of the deduced amino acid sequences are similar to transfer proteins. The majority of the transfer proteins are highly homologous to proteins of Y. bercovieri strain ATCC 43970, with identities between 94% and 100% (Table 5). Unfortunately, there is yet no information available about plasmids of this species. Nevertheless, a stretch of 33 kb (pYE854 positions 51500 to 84500) is nearly identical to a published whole-genome shotgun sequence (Y berA_01_29, NCBI accession no. NZ_AALC01000029) of the Y. bercovieri strain. This stretch comprises the whole Tra2 region and adjacent DNA sequences of pYE854 (see below). The ORF analysis suggests that, in the Tra2 region, mating-pair formation (Mpf) proteins are encoded. Mpf proteins form a membrane-associated apparatus that synthesizes and assembles mature conjugative pili on the cell surface. The conjugative pili facilitate the initial contact with the recipient cell, resulting in the formation of a stable mating pair. The pYE854 products are related to Mpf proteins of several transfer systems, e.g., F and R100 (IncF), R27 (IncH), RP4 (IncP), and R388 (IncW), and of the type IV secretion system of the Ti plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens.

To determine which of the pYE854 tra genes are essential for conjugation, the plasmid was mutagenized by using an in vivo transposon mutagenesis system (see Materials and Methods). The analysis of the insertion sites of the marker gene disclosed that many insertions occurred hot spot-like within transposase genes (data not shown). However, insertions were also found in other ORFs (Table 2). All mutants were investigated in terms of their capability to conjugate and to mobilize pYV. Not surprisingly, insertions leading to a loss of conjugation and mobilization were mainly found in ORFs located in the Tra regions. All seven insertions within the putative traI gene (ORF 36) resulted in a deficit of transfer. Within the Tra2 region, several genes supposed to be important for conjugation were mutagenized (Table 2). Insertions in ORF 164 (TraN) only decreased mating ability slightly, consistent with the results of observations of plasmids F and R100-1 (37). All other insertions yielded defective mutants unable to conjugate and to mobilize the Yersinia virulence plasmid. In addition to tra, insertions resulting in a negative Tra phenotype were also observed in ORF 122. The function of this gene is not known. Its predicted product shows some similarity to a permease of Yersinia belonging to the major facilitator superfamily which comprises translocators exporting antibiotics and other small molecules.

The pYE854 replicon belongs to a new incompatibility group.

A search for ORFs encoding probable Rep proteins was undertaken to identify DNA regions on pYE854 which might be important for plasmid replication. Two genes (ORF 11 and ORF 187) possibly involved in replication have been detected. While the deduced ORF 11 product shows some similarity to a primase of Clostridium difficile, ORF 187, located upstream of the Tra2 region, encodes a protein that is similar (30% identity) to the Rep protein of the Clostridium perfringens plasmid pIP404 (Table 5). The rep gene of pIP404 is sufficient, in conjunction with some repetitive origin-like sequences located downstream of the gene, to drive plasmid replication (21, 22). We constructed a replicative miniplasmid derivative of pYE854 by digesting the plasmid with PstI and ligating the resulting restriction fragments with a tetracycline resistance gene. Upon transformation of E. coli DH5α, plasmid pJH1010, comprising the 50,189-bp PstI restriction fragment and tet (Fig. 5), was isolated. By using other restriction endonucleases, the size of the minimal replicon could be further reduced. The smallest miniplasmid, pJH1015, is composed of the 8,350-bp NdeI restriction fragment of pYE854 ligated to the tetracycline resistance gene. Besides ORF 187, pJH1015 contains the pYE854 ORFs 183, 185, 191, 194, 196, and 202 (Fig. 5). The relationship of the putative ORF 187 product to a replication protein of Clostridium prompted us to investigate whether pJH1015 may replicate in gram-positive bacteria. For that reason, several Bacillus strains belonging to various species (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were transformed with the plasmid. We could not isolate any transformant containing pJH1015, while plasmid pUB110 (36) could be readily introduced into the bacteria, indicating that the pYE854 derivative does not replicate in Bacillus species.

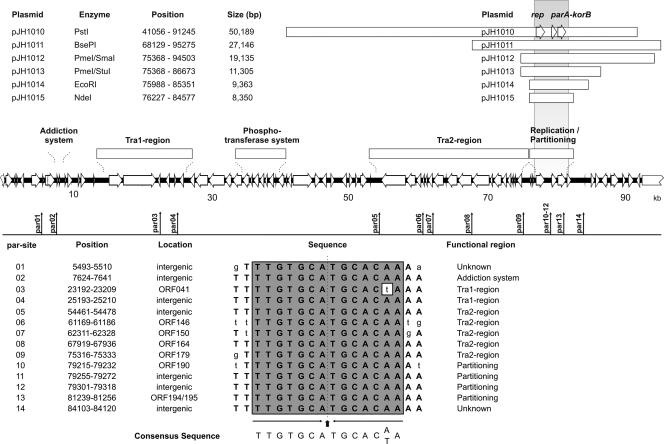

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the pYE854 replication and partitioning (par) region. The upper panel shows miniplasmid derivatives of pYE854 retaining replicative competence. In the middle, the linear gene map of pYE854 is given. The locations of putative centromere sites are indicated. The lower panel shows the sequences of the predicted centromere sites and their positions on the plasmid. Lowercase letters show nucleotides diverging from the dyad symmetry of the palindromes. The vertical arrow and dotted line represent the center of dyad symmetry. Half sides of the palindrome are indicated by horizontal arrows.

To determine the incompatibility group of pYE854, the PCR-based replicon typing scheme developed by Carattoli et al. (6), which covers 18 common plasmid incompatibility groups among the Enterobacteriaceae, was applied. Since the recommended primers did not match pYE854, the incompatibility determinants of the reference plasmids were amplified by PCR and the products were hybridized with pYE854. Even by Southern hybridization, pYE854 could not be affiliated to one of the 18 incompatibility groups (data not shown). We also studied incompatibility under in vivo conditions by introducing pYE854 into E. coli strains containing plasmids belonging to the Inc groups A, B, C, H, I, J, M, N, P, or Q (data not shown). The Yersinia plasmid showed compatibility to all of the investigated replicons. Hence, pYE854 belongs to a new incompatibility group.

Plasmid maintenance is accomplished by a partitioning and an addiction system.

Next to the putative rep gene of pYE854, there are two ORFs (191 and 194) which apparently belong to a plasmid partitioning system (Fig. 2). Their predicted products are nearly identical to proteins of Y. bercovieri and also related to partitioning proteins (Par) of IncP plasmids (Table 5). While the ORF 191 product is similar to ParA-like ATPases, the deduced product of ORF 194 may represent the transcriptional repressor ParB. This protein binds to a centromere target site (parC) which consists of repetitive sequences often situated close to the par operon. A search for possible centromere sites revealed 14 nearly identical copies of a 16-bp palindromic sequence scattered on pYE854 (Fig. 5). Three copies of this sequence are located upstream of the parA gene. This region also contains a number of possible promoter sequences, which suggests that the detected repeats are binding sites for the partitioning proteins and probably involved in the autoregulation of par expression.

Stable maintenance of pYE854 might also be achieved by an addiction system (toxin-antitoxin system) responsible for postsegregational elimination of plasmidless cells from a bacterial population. ORFs 15 and 16 apparently encode a toxin and an antitoxin, respectively. Both products are similar to proteins of the bacteriophage N15 that were shown to stabilize heterologous replicons (15). Moreover, overexpression of the N15 toxin gene in E. coli resulted in a bacteriostatic effect discernible by elongation of bacterial cells and growth cessation. To find out whether the pYE854 ORF 15 also has adverse effects on bacterial growth, the gene was amplified by PCR and inserted into expression vector pMS470Δ8, which contains an inducible tac promoter (3). Upon transformation, the isolated E. coli clones were analyzed by sequencing. All plasmids revealed mutations within ORF 15 leading to amino acid exchanges which probably inactivated the toxin. As the cloned DNA fragment is very small (333 bp), it can be assumed that the intact gene has deleterious effects on the bacteria. This was corroborated by the fact that we could clone PCR fragments containing either the antitoxin gene or both the toxin and antitoxin genes.

Plasmid curing was examined by treating Y. enterocolitica strain 29854 with acridine orange at a 0.1 mM concentration. Using this concentration, the plasmid could easily be cured from its original host strain (data not shown).

pYE854 is a cryptic plasmid.

As mentioned above, we identified a stretch of genes (ORFs 73, 75, 79, 82, 86, and 89) on pYE854 which obviously code for components belonging to a PTS (Fig. 2, Table 5). A similar cluster exists in V. vulnificus YJ016 and also in Psychromonas and Y. pseudotuberculosis. The products of this gene cluster might be important for the uptake of mannose and fructose. By using an API 50 CHB/E system (bioMerieux, Nürtingen, Germany), we tested if a Yersinia strain harboring pYE854 is more capable of utilizing sugars and other carbohydrates than the respective strain without the plasmid. We did not detect any differences between the strains. Thus, it is doubtful whether the gene cluster plays a role in bacterial growth. The same holds true for ORFs 97 and 219, whose predicted products show a relationship to proteins involved in heavy metal resistance (Table 5). A test on agar containing arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, or zinc revealed the sensitivity of the Yersinia strains to these elements, regardless of the plasmid content. Therefore, at the present level of knowledge, pYE854 has to be considered cryptic.

pYE966, a pYE854-related plasmid of a pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strain.

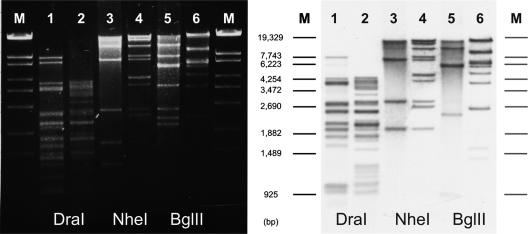

Mating studies conducted with pYE854 showed that this plasmid is transmissible with high frequencies. To find out whether similar plasmids are prevalent in Yersinia, we used pYE854 as the probe for DNA hybridization experiments with plasmid preparations of approximately 50 strains of the BfR strain collection. One of the plasmids investigated, pYE966, isolated from pathogenic Y. enterocolitica serogroup O:5,27 strain 966/89 (Table 1) displayed strong hybridization signals (Fig. 6). According to the restriction patterns obtained, pYE966 has an approximate size of 70 kb. Two DNA regions of pYE854 are obviously missing in the smaller plasmid (Fig. 2). Using primers deduced from pYE854, genes of plasmid pYE966 coding for a number of transfer proteins, the putative replication protein (ORF 187 product), and the partitioning and addiction systems were amplified and sequenced (data not shown). In addition, the oriT region of pYE966 was analyzed. We detected only single mismatches to the pYE854 sequences that did not result in amino acid exchanges, confirming that the plasmids are closely related. The conjugative properties of pYE966 have been studied and compared to those of pYE854. Like its larger relative, pYE966 is a self-transmissible plasmid that is able to mobilize pYV, with slightly higher efficiencies even than pYE854 (Table 4). These findings document that the DNA regions of pYE854 which are missing in pYE966 are apparently not important for plasmid transfer.

FIG. 6.

Southern hybridization of pYE854 with pYE966. Several restriction digests of pYE854 were separated on an 0.8% agarose gel and hybridized to labeled pYE966 DNA. Lane M, marker (λ Eco130I); lanes 1, 3, and 5, pYE854; lanes 2, 4, and 6, pYE966.

DISCUSSION

The Yersinia virulence plasmid pYV can be mobilized by conjugative helper plasmids. Allen et al. (2) demonstrated that E. coli strains containing the F factor are able to mobilize pYV of Y. pestis. Later on, the DNA sequences located within the low-calcium response (lcr) region of pYV were determined to promote plasmid transfer (1). Since the lcr region of the plasmid is conserved in the three medically important Yersinia species, it can be assumed that the virulence plasmids of Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis also possess an oriT. However, there is no report on the transmission of pYV of these species. Moreover, mobilization of the virulence plasmid by Yersinia donor strains harboring an indigenous conjugative plasmid has not been described yet. As there was a gap of knowledge about self-transmissible plasmids in Yersinia, we searched for conjugative plasmids and isolated two similar plasmids, one from a pathogenic and the other from a nonpathogenic Y. enterocolitica strain. Both plasmids have the potential to mobilize pYV of Y. pseudotuberculosis and also the virulence plasmid of Y. enterocolitica. A closely related conjugative plasmid might also be present in Y. bercovieri strain ATCC 43970 because more than 50% of the pYE854 DNA sequences, including those encoding transfer and replication proteins, were identified in this species. Thus, a group of related, self-transmissible plasmids is possibly widespread in Yersinia. This speculation is underpinned by our data on the transfer properties of the conjugative plasmids. We observed conjugation with high frequencies into a broad range of Yersinia strains. The mobilization of pYV was less efficient and restricted to pathogenic Yersinia strains and one of the biogroup 1A strains investigated. Therefore, dissemination of the virulence plasmid within Yersinia populations (e.g., in pigs) which often comprise pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains cannot be ruled out but does not seem to be very common.

The sequence analysis of pYE854 and pYE966 demonstrated that these plasmids are very similar. They show a relationship to the F factor, especially in the transfer regions, which, unlike the tra operon of F, are separated on the Yersinia plasmids. In F, four proteins (TraD, TraI, TraM, and TraY) are involved in DNA metabolism during transfer (16). The sequence analysis of pYE854 revealed two products (TraD and TraI) that might be part of the relaxosome of this plasmid. Counterparts to TraM and TraY of the F factor have not been identified. Interestingly, the oriT of pYE854, which is also similar to those of the F group, was identified contiguous to the predicted traD gene, while the oriT of the F factor lies adjacent to the traM gene, approximately 23 kb away from traD (50). We have investigated whether F is able to mobilize a recombinant plasmid containing the oriT of pYE854 but could not detect any transmission of this plasmid (data not shown). Hence, although some proteins of the pYE854 relaxosome and the oriT sequence are similar to F, other transfer proteins and/or binding sites (e.g., for IHF, TraM, or TraY) are apparently too divergent to allow mobilization. We also searched for possible oriT sequences on the Yersinia virulence plasmid, especially within the lcr region. Several families of oriT nic regions and the oriT of pYE854 provided the basis for the search (52). Numerous sequences have been detected all over pYV, but none revealed strong similarity to one of the compared sequences. Therefore, the determination of the oriT of pYV requires further experiments, as already performed with pYE854.

Among the deduced pYE854 products belonging to the Mpf system, we found seven proteins showing similarity to pilus assembly proteins (TraB, TraC, TraE, TraF, TraH, TraU, and TrbC) of the F factor (19). Their predicted molecular masses are also in good agreement with those of the corresponding F proteins. The same holds true for two pYE854 products that are related to the mating-aggregate stabilization proteins TraG and TraN of F (17, 41). By contrast, a product similar to the pilus subunit pilin of F is not encoded by pYE854 (18). Taking the data on similarities of the transfer proteins and the oriT together, it can be reasoned that pYE854 and pYE966 are F-like plasmids, though this classification does not refer to the replicons of the Yersinia plasmids.

We could not allocate the plasmids to a known incompatibility group. Their replicons show some relationship to the Clostridium plasmid pIP404 but are obviously not functional in gram-positive bacilli. Stable replication in members of the Enterobacteriaceae apparently requires the partitioning system because we were unable to isolate a replicative miniplasmid deprived of the par operon. Since four identical copies of the predicted centromere sites are situated close to or within the par operon, it can be assumed that they are also of importance for miniplasmid maintenance. The stabilization of the native plasmids might be accomplished by additional centromere-like sites scattered on the plasmids and by an addiction system. Interestingly, the identified toxin-antitoxin system is related to that of the temperate E. coli phage N15, whose prophage is a linear plasmid (43). Besides pYE854, Y. enterocolitica strain 29854 harbors the linear plasmid prophage PY54, which is related to N15 but does not possess an addiction system. This observation raises the question of whether the addiction system of pYE854 was once acquired from PY54.

The isolated conjugative plasmids are large in size and contain numerous ORFs, but at present, they have to be regarded as cryptic. This might be caused by the fact that only 25% of the deduced gene products revealed similarities to known proteins. Apart from tra genes and those implicated in plasmid replication and maintenance, the functions of the ORFs could not be assigned. Although genes potentially encoding a PTS or conferring heavy metal resistance have been identified on pYE854, we were not able to demonstrate the respective functions. Perhaps additional genes essential for functionality are lacking on the plasmid, or we did not test for the right compounds (e.g., heavy metals). However, it has also been reported that PTSs are sometimes associated with bacterial virulence (53). The question of whether pYE854 plays a role in the virulence of Yersinia cannot be answered at the moment. Besides the PTS genes, the plasmid contains two genes (ORF 62 and ORF 73) whose products are similar to a hyaluronate lyase and a glucuronyl hydrolase, respectively, of Vibrio, proteins which are suggested to be virulence factors of some gram-positive pathogens (34, 40). Nevertheless, the finding that Y. enterocolitica 29854 can be cured from its conjugative plasmid without any consequences for growth in broth suggests that pYE854 and, presumably, also pYE966 are not pivotal for the bacteria under laboratory conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ronald Sladek and Isabell Hamann for initial work on the conjugative plasmids and Barbara Freytag for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to E.L.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 November 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, J., W. L. Kuhnert, and R. M. Zsigray. 1995. Transfer of the virulence plasmid of Yersinia pestis O:19 is promoted by DNA sequences contained within the low calcium response region. Contrib. Microbiol. Immunol. 13285-289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, J. R., W. R. Chesbro, and R. M. Zsigray. 1987. Mobilization of the Vwa plasmid of Yersinia pestis by F-containing strains of Escherichia coli. Contrib. Microbiol. Immunol. 9332-341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzer, D., G. Ziegelin, W. Pansegrau, V. Kruft, and E. Lanka. 1992. KorB protein of promiscuous plasmid RP4 recognizes inverted sequence repetitions in regions essential for conjugative plasmid transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 201851-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottone, E. J. 1997. Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10257-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner, D. J. 1979. Speciation in Yersinia. Contrib. Microbiol. Immunol. 533-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carattoli, A., A. Bertini, L. Villa, V. Falbo, K. L. Hopkins, and E. J. Threlfall. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J. Microbiol. Methods 63219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.China, B., T. Michiels, and G. R. Cornelis. 1990. The pYV plasmid of Yersinia encodes a lipoprotein, YlpA, related to TraT. Mol. Microbiol. 41585-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook, D. M., and S. K. Farrand. 1992. The oriT region of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid pTiC58 shares DNA sequence identity with the transfer origins of RSF1010 and RK2/RP4 and with T-region borders. J. Bacteriol. 1746238-6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornelis, G., P. M. Bennett, and J. Grinsted. 1976. Properties of pGC1, a lac plasmid originating in Yersinia enterocolitica 842. J. Bacteriol. 1271058-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelis, G. R., and H. Wolf-Watz. 1997. The Yersinia Yop virulon: a bacterial system for subverting eukaryotic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 23861-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covarrubias, L., and F. Bolivar. 1982. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. VI. Plasmid pBR329, a new derivative of pBR328 lacking the 482-base-pair inverted duplication. Gene 1779-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covarrubias, L., L. Cervantes, A. Covarrubias, X. Soberon, I. Vichido, A. Blanco, Y. M. Kupersztoch-Portnoy, and F. Bolivar. 1981. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. V. Mobilization and coding properties of pBR322 and several deletion derivatives including pBR327 and pBR328. Gene 1325-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1726568-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devereux, J., P. Haeberli, and O. Smithies. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dziewit, L., M. Jazurek, L. Drewniak, J. Baj, and D. Bartosik. 2007. The SXT conjugative element and linear prophage N15 encode toxin-antitoxin-stabilizing systems homologous to the tad-ata module of the Paracoccus aminophilus plasmid pAMI2. J. Bacteriol. 1891983-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everett, R., and N. Willetts. 1980. Characterisation of an in vivo system for nicking at the origin of conjugal DNA transfer of the sex factor F. J. Mol. Biol. 136129-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Firth, N., and R. Skurray. 1992. Characterization of the F plasmid bifunctional conjugation gene, traG. Mol. Gen. Genet. 232145-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost, L. S., B. B. Finlay, A. Opgenorth, W. Paranchych, and J. S. Lee. 1985. Characterization and sequence analysis of pilin from F-like plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 1641238-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frost, L. S., K. Ippen-Ihler, and R. A. Skurray. 1994. Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor. Microbiol. Rev. 58162-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galimand, M., A. Guiyoule, G. Gerbaud, B. Rasoamanana, S. Chanteau, E. Carniel, and P. Courvalin. 1997. Multidrug resistance in Yersinia pestis mediated by a transferable plasmid. N. Engl. J. Med. 337677-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garnier, T., and S. T. Cole. 1988. Complete nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of the bacteriocinogenic plasmid, pIP404, from Clostridium perfringens. Plasmid 19134-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garnier, T., and S. T. Cole. 1988. Identification and molecular genetic analysis of replication functions of the bacteriocinogenic plasmid pIP404 from Clostridium perfringens. Plasmid 19151-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gridnev, V. A., V. F. Dziubak, V. G. Zagoruiko, L. G. Gridneva, and Z. U. Zainulina. 1990. Conjugative R-plasmid resistance of the causative agents of Yersinia infection. Antibiot. Khimioter. 3519-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guiyoule, A., G. Gerbaud, C. Buchrieser, M. Galimand, L. Rahalison, S. Chanteau, P. Courvalin, and E. Carniel. 2001. Transferable plasmid-mediated resistance to streptomycin in a clinical isolate of Yersinia pestis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 743-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall, M. C., and S. W. Matson. 1999. Helicase motifs: the engine that powers DNA unwinding. Mol. Microbiol. 34867-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harley, C. B., and R. P. Reynolds. 1987. Analysis of E. coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 152343-2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawley, D. K., and W. R. McClure. 1983. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 112237-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrero, M., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1726557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hertwig, S., I. Klein, J. A. Hammerl, and B. Appel. 2003. Characterization of two conjugative Yersinia plasmids mobilizing pYV. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 52935-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hertwig, S., I. Klein, R. Lurz, E. Lanka, and B. Appel. 2003. PY54, a linear plasmid prophage of Yersinia enterocolitica with covalently closed ends. Mol. Microbiol. 48989-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hertwig, S., I. Klein, V. Schmidt, S. Beck, J. A. Hammerl, and B. Appel. 2003. Sequence analysis of the genome of the temperate Yersinia enterocolitica phage PY54. J. Mol. Biol. 331605-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinnebusch, B. J., M. L. Rosso, T. G. Schwan, and E. Carniel. 2002. High-frequency conjugative transfer of antibiotic resistance genes to Yersinia pestis in the flea midgut. Mol. Microbiol. 46349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffmann, B., E. Strauch, C. Gewinner, H. Nattermann, and B. Appel. 1998. Characterization of plasmid regions of foodborne Yersinia enterocolitica biogroup 1A strains hybridizing to the Yersinia enterocolitica virulence plasmid. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21201-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Itoh, T., W. Hashimoto, B. Mikami, and K. Murata. 2006. Crystal structure of unsaturated glucuronyl hydrolase complexed with substrate: molecular insights into its catalytic reaction mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 28129807-29816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanazawa, Y., and T. Kuramata. 1975. Transmission of drug-resistance through conjugation in Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. II. With special reference to streptomycin resistant strains isolated from men and domestic animals. Jpn. J. Antibiot. 28538-541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keggins, K. M., P. S. Lovett, and E. J. Duvall. 1978. Molecular cloning of genetically active fragments of Bacillus DNA in Bacillus subtilis and properties of the vector plasmid pUB110. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 751423-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klimke, W. A., and L. S. Frost. 1998. Genetic analysis of the role of the transfer gene, traN, of the F and R100-1 plasmids in mating pair stabilization during conjugation. J. Bacteriol. 1804036-4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewin, A., S. Hertwig, E. Strauch, and B. Appel. 1998. Is natural genetic transformation a mechanism of horizontal gene transfer in Yersinia? J. Basic Microbiol. 3817-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewin, A., E. Strauch, S. Hertwig, B. Hoffmann, H. Nattermann, and B. Appel. 1996. Comparison of plasmids of strains of Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 1A with the virulence plasmid of a pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strain. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 28552-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makris, G., J. D. Wright, E. Ingham, and K. T. Holland. 2004. The hyaluronate lyase of Staphylococcus aureus: a virulence factor? Microbiology 1502005-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]