Abstract

Escherichia coli exhibits chemotactic responses to sugars, amino acids, and dipeptides, and the responses are mediated by methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs). Using capillary assays, we demonstrated that Escherichia coli RP437 is attracted to the pyrimidines thymine and uracil and the response was constitutively expressed under all tested growth conditions. All MCP mutants lacking the MCP Tap protein showed no response to pyrimidines, suggesting that Tap, which is known to mediate dipeptide chemotaxis, is required for pyrimidine chemotaxis. In order to confirm the role of Tap in pyrimidine chemotaxis, we constructed chimeric chemoreceptors (Tapsr and Tsrap), in which the periplasmic and cytoplasmic domains of Tap and Tsr were switched. When Tapsr and Tsrap were individually expressed in an E. coli strain lacking all four native MCPs, Tapsr mediated chemotaxis toward pyrimidines and dipeptides, but Tsrap did not complement the chemotaxis defect. The addition of the C-terminal 19 amino acids from Tsr to the C terminus of Tsrap resulted in a functional chemoreceptor that mediated chemotaxis to serine but not pyrimidines or dipeptides. These results indicate that the periplasmic domain of Tap is responsible for detecting pyrimidines and the Tsr signaling domain confers on Tapsr the ability to mediate efficient chemotaxis. A mutant lacking dipeptide binding protein (DBP) was wild type for pyrimidine taxis, indicating that DBP, which is the primary chemoreceptor for dipeptides, is not responsible for detecting pyrimidines. It is not yet known whether Tap detects pyrimidines directly or via an additional chemoreceptor protein.

Chemotaxis is the ability of motile bacteria to detect and respond to specific chemical ligands. Chemotactic responses of Escherichia coli and other motile bacteria are accomplished by signal transduction between transmembrane signal transducers, also known as methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs), and the flagellar motor. The four MCPs in E. coli are involved in directly or indirectly sensing chemical attractants, many of which are good carbon and energy sources for the organism. Tar mediates taxis toward aspartate and maltose (41), while the primary attractant detected by Tsr is serine (22). Taxis toward galactose and ribose is mediated by Trg (23), and Tap is required for taxis toward dipeptides (32).

Tsr, Tar, Trg, and Tap share significant sequence similarities and a common domain organization (45). Each protein has a periplasmic ligand-binding domain bracketed by two transmembrane (TM) domains, followed by a cytoplasmic signaling domain. MCP dimers form ternary complexes with the histidine kinase CheA and the adaptor protein CheW, both of which are located in the cytoplasm. Upon binding a chemoeffector, the MCP undergoes a conformational change, resulting in an altered rate of CheA autophosphorylation. Phosphorylated CheA is able to transfer phosphate to the response regulator CheY and the methylesterase CheB to modulate their activities. Phosphorylated CheY interacts with the flagellar motor complex and controls the direction of rotation. The methyltransferase CheR and the methylesterase CheB modulate the methylation level of MCPs and allow cell adaptation to chemoeffectors. Details of this complex signal transduction mechanism can be found in recent reviews (7, 36, 40, 45).

No new attractants for E. coli have been identified in several years, but a recent study demonstrated that E. coli utilizes the pyrimidines thymine and uracil as the sole nitrogen sources at room temperature via a newly discovered pathway (29). To date, however, there have been no reports regarding chemotaxis to these compounds by E. coli. In this study, we investigated the chemotactic response of E. coli to pyrimidines. This work revealed a new role for the MCP Tap in chemotaxis, that of mediating the response to the pyrimidines thymine and uracil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

All bacterial strains used in this work are derivatives of E. coli strain RP437 (Table 1). The dppA deletion mutant was constructed using the method described by Datsenko and Wanner (12). Briefly, the Red helper plasmid pKD46 was introduced into RP437 to express λ Red recombinase (Table 1). A kanamycin resistance gene flanked by FRT (FLP recognition target) sites was PCR amplified with the primers dppAH1P4 and dppAH2P1, using pKD13 as the template (Table 1). The primers have 36 nucleotide extensions that are homologous to the flanking regions of dppA, in order to allow λ Red-mediated recombination to occur in the later step. The PCR product was introduced into RP437(pKD46) by electroporation, and kanamycin-resistant transformants were selected and purified. The ΔdppA::Km mutation in strain XL1 was confirmed by PCR and sequence analysis (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Relevant characteristics or primer sequencea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| RP437 | Wild type reference strain for chemotaxis; F−thr-1 leuB6 his-4 metF159 thi-1 ara-14 lacY1 mtl-1 xyl-5 rpsL136 tonA31 tsx-78 eda-50 | 37 |

| RP1131 | RP437 trg-2::Tn10 | J. S. Parkinson |

| RP2361 | RP437 Δtar-386-2 | 32, 39 |

| RP3525 | RP437 Δtap-365-4 Δ(lac)U169 thr+leu+ | 32, 39 |

| RP5700 | RP437 Δtsr-7028 | J. S. Parkinson |

| UU1250 | RP437 Δaer-1 ygjG::Gm Δtsr-7028 Δ(tar-tap)5201 zbd::Tn5 Δtrg-100 thr+met+ | 9 |

| UU1615 | RP437 Δaer-1 ygjG::Gm Δ(tar-tap)5201 zbd::Tn5 Δtrg-100 thr+met+ | 4 |

| UU1624 | RP437 Δaer-1 ygjG::Gm Δtsr-7028 Δtap-3654 zbd::Tn5 Δtrg-100 thr+met+ | 4 |

| UU1625 | RP437 Δaer-1 ygjG::Gm Δtsr-7028 zbd::Tn5 Δtrg-100 | J. S. Parkinson |

| XL1 | RP437 ΔdppA::Km | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRR48 | lacIq/ptac cloning vector, Apr | 42 |

| pXL2 | PCR fragment of tsr cloned into pRR48, Apr | This study |

| pXL3 | Chimeric fragment tsrap cloned into pRR48, Apr | This study |

| pXL4 | Chimeric fragment tapsr cloned into pRR48, Apr | This study |

| pXL5 | PCR fragment of tap cloned into pRR48, Apr | This study |

| pXL8 | Chimeric fragment tsrap plus the last 5 codons of tsr in pRR48, Apr | This study |

| pXL9 | Chimeric fragment tsrap plus the last 19 codons of tsr in pRR48, Apr | This study |

| pKD13 | Template plasmid, derivative of pANTSγ that contain an FRT-flanked kanamycin resistance gene | 12 |

| pKD46 | Red helper plasmid, derivative of pINT-ts which contain araC-ParaB and γ β exo | 12 |

| Primers | ||

| tsrNF | 5′-GCCGCCGCATTAATGTTAAAACGTATCAAAATTGTGACCAGC-3′ | This study |

| tsrNR | 5′-CCACGCAAAGCCTGCTGCATATGGCGCAAACTCTCTGCC-3′ | This study |

| tsrCF | 5′-GCCATTTTTGCCAGTCTGAAGCATATGCAGGGAGAGCTGATGC-3′ | This study |

| tsrCR | 5′-GCCGCGCCAAGCTTTAAAATGTTTCCCAGTTCTCCTCGC-3′ | This study |

| tapNF | 5′-CGCCGCATTAATGTTTAATCGTATTCGAATTTCGACCACGC-3′ | This study |

| tapNR | 5′-GCATCAGCTCTCCCTGCATATGCTTCAGACTGGCAAAAATGGC-3′ | This study |

| tapCF | 5′-GCAGAGAGTTTGCGCCATATGCAGCAGGCTTTGCGTGGGACGG-3′ | This study |

| tapCR | 5′-GCCGCGCCAAGCTTCAGGATACCACTGGCGCAATTTGTAACTGC-3′ | This study |

| tapCR5aa | 5′-GCCGCGCCAAGCTTCAGGATACCACTGGCGCAATTTGTAACTGC-3′ | This study |

| tapCRp | 5′-GGATACCACTGGCGCAATTTG-3′ | This study |

| 19aaFp | 5′-CCAGCTGCGCCGCGTAAAATGG-3′ | This study |

| 19aaR | 5′-GCCGCGCCAAGCTTTAAAATGTTTCCCAGTTC-3′ | This study |

| dppAH1P4 | 5′-AACAACAAACATCACAATTGGAGCAGAATAATGCGTATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ | This study |

| dppAH2P1 | 5′-GCCATCAGTCTTGTATGGCTTTTAATTATTCGATAGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′ | This study |

Underlined bases indicate the positions of restriction sites.

A series of chimeric tap-tsr chemoreceptor genes was generated and cloned into the expression vector pRR48, which confers ampicillin resistance, carries the lacIq gene, and allows the expression of genes from the tac promoter (42). The plasmids pXL2 and pXL5 were constructed by cloning the AseI-HindIII fragments of the PCR-amplified tsr and tap genes, respectively, into NdeI-HindIII-digested pRR48 (primers for the amplification of tsr were tsrNF and tsrCR; those for tap were tapNF and tapCR [Table 1]). To construct pXL3 and pXL4, the 5′ half of tsr and the 5′ half of tap were PCR amplified (primers for tsr were tsrNF and tsrNR, and primers for tap were tapNF and tapNR [Table 1]), gel purified, and cut with AseI and NdeI. They were ligated with NdeI-HindIII fragments carrying the 3′ half of tap (PCR amplified with the primers tapCF and tapCR [Table 1]) or the 3′ half of tsr (PCR amplified with the primers tsrCF and tsrCR [Table 1]), respectively. The resulting chimeric genes tsrap and tapsr were inserted into the pRR48 plasmid under the control of the inducible tac promoter. tsrapt5 was constructed by PCR amplification of tsrap with the primers tsrNF and tapCR5aa (Table 1). tsrapt19 was constructed by the ligation of tsrap (PCR amplified with primers tsrNF and tapCRp [Table 1]) and the region encoding the 19 amino acids at the C terminus of tsr (amplified with primers 19aaFp and 19aaR [Table 1]). These two fragments were also inserted into pRR48, resulting in the plasmids pXL8 and pXL9. During the construction of pXL3 and pXL4, a single nucleotide change in codon 255 of tap was made to create an NdeI site, which did not appear to affect the receptor function of our new chimeric proteins or those of previously constructed Tar-Tap hybrids (43). All of the constructs were sequenced at the University of California, Davis, DNA sequence facility to verify the sequences of the inserted fragments.

Growth media and chemicals.

Strains were maintained on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (13). For capillary assays and growth studies, strains were grown in H1 minimal salts medium (2) containing 25 mM glycerol as the carbon source, 0.5 mM each of methionine, leucine, histidine, and threonine, and 1 μg/ml thiamine to satisfy auxotrophic requirements. When pyrimidines were used as the nitrogen source, (NH4)2SO4 was eliminated from the medium, and the pyrimidine was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. E. coli cultures were grown at 30°C for chemotaxis assays. E. coli strains carrying pRR48 derivatives were grown in the presence of 100 μg/ml ampicillin and were induced for 4 h with 200 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

Chemotaxis assays.

Bacterial cells were harvested at the early exponential phase (when the optical density at 660 nm [OD660] was between 0.3 and 0.4) by centrifugation at 4,500 rpm for 5 min and washed once with chemotaxis buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate buffer [pH 7.0], 0.1 mM disodium EDTA) (37). Quantitative capillary assays were carried out as described previously, with slight modifications (2). One-microliter capillaries were filled with 0.63 μl of chemotaxis buffer or an attractant dissolved in chemotaxis buffer under vacuum, as described previously (33). Washed cells were suspended in chemotaxis buffer to an OD660 of approximately 0.1 (approximately 8 × 107 cells per ml). After the solutions were incubated for 30 min at 30°C, the capillary contents were collected and diluted, and cells were enumerated as CFU by plate counts on LB plates. Chemotactic responses were also observed directly with the modified capillary assay at room temperature (18). For this assay, microcapillaries containing chemicals dissolved in chemotaxis buffer in 2% low-melting-temperature agarose were introduced into suspensions of motile cells in the same buffer at an OD660 of approximately 0.1, and the accumulation of cells at the capillary tip was visualized and photographed by microscopy at a magnification of ×40.

RESULTS

Wild-type E. coli responds chemotactically to pyrimidines.

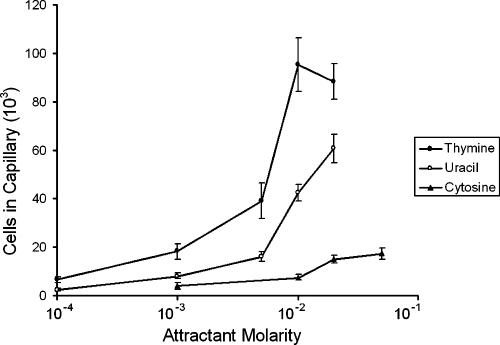

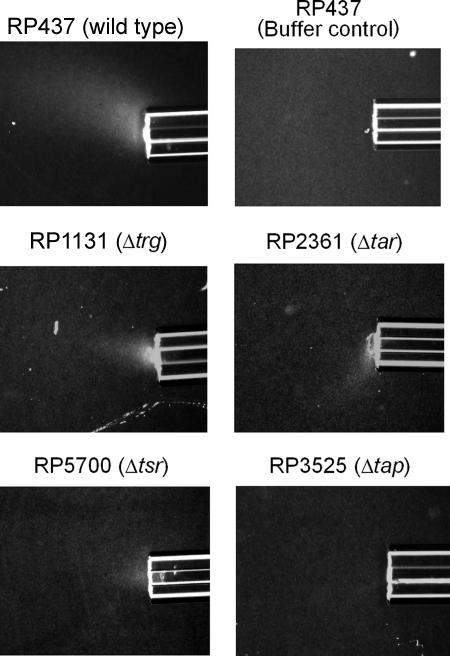

Quantitative capillary assays were used to measure the chemotactic responses of E. coli RP437 to various concentrations of pyrimidines at 30°C. Each compound was tested at concentrations up to the limit of solubility. In all experiments, negative controls (chemotaxis buffer) and positive controls (1 mM aspartate) were included. E. coli RP437, which is wild type for chemotaxis, responded to thymine and uracil (Fig. 1). No response was observed for 20 mM cytosine in a modified capillary assay (data not shown), and only very weak responses were detected to relatively high concentrations of cytosine (20 mM and 50 mM) in quantitative capillary assays (Fig. 1). Of the three pyrimidines tested, thymine was the strongest attractant and had the lowest threshold concentration. The chemotactic responses of E. coli RP437 to 20 mM thymine (Fig. 2) and to 20 mM uracil (data not shown) were visualized directly by microscopy of modified capillary assays at room temperature. Because the wild-type response to cytosine was very weak, subsequent studies focused on the responses to thymine and uracil.

FIG. 1.

Concentration response curves for chemotactic responses to pyrimidines by E. coli RP437 (wild type). Cells were grown at 30°C in H1 minimal salts medium containing 25 mM glycerol, the required amino acids, and thiamine. Assays were performed at 30°C with each pyrimidine up to its limit of solubility. Results are the averages of at least 10 capillaries from at least three independent experiments; error bars indicate standard errors. Data are not corrected for background accumulation in capillaries containing buffer only (∼5 × 103 cells).

FIG. 2.

Chemotactic responses of wild-type and mutant E. coli strains to thymine in modified capillary assays. Cells were grown as described in the legend to Fig. 1. All capillaries contained 20 mM thymine in chemotaxis buffer solidified with 2% low-melting-temperature agarose, except for the top right capillary, which contained only buffer solidified with agarose to show the absence of any response by the wild type to buffer. Assays were carried out at room temperature for 20 min as described in Materials and Methods.

E. coli RP437 was able to utilize each of the pyrimidines as the sole nitrogen source. When cells were grown in minimal medium at room temperature (21°C) with 25 mM glycerol as the sole carbon source and 1 mM pyrimidine as the sole nitrogen source, the doubling times were 9.3 h, 11.8 h, and 11.2 h for cytosine, thymine, and uracil, respectively. However, when cells were grown at 37°C, only cytosine was used as the sole nitrogen source by E. coli RP437. The chemotactic response of cells grown with pyrimidines at room temperature was not improved compared to that of cells grown with ammonium sulfate as the sole nitrogen source (data not shown). Glutamine is typically used as the sole nitrogen source for nitrogen limitation studies (24). Therefore, cells were grown with 5 mM glutamine as the sole nitrogen source and were assayed for their chemotactic responses to pyrimidines. The responses observed with qualitative capillary assays were similar to those for cells grown with ammonium sulfate as the sole nitrogen source (data not shown). Together, these results indicate that the chemotactic response to pyrimidines was constitutively expressed under all tested growth conditions.

Tap mediates chemotaxis toward pyrimidines.

To determine which MCP was responsible for pyrimidine chemotaxis, qualitative capillary assays were used to screen single and multiple MCP knockout mutants (kindly provided by J. S. Parkinson) for chemotactic response to 20 mM thymine or 20 mM uracil. RP3525, a Δtap mutant, showed no response to either pyrimidine, while RP1131 (trg::Tn10), RP2361 (Δtar), and RP5700 (Δtsr) retained the ability to respond (Fig. 2; Table 2). Among the multiple MCP knockout mutants tested, UU1250 (Δ[tar-tap] Δtsr Δtrg), UU1615 (Δ[tar-tap] Δtrg), and UU1624 (Δtsr Δtrg Δtap) were not attracted to pyrimidines (Table 2). UU1625, a strain carrying only Tap and Tar, responded to pyrimidines (Table 2). In summary, all tested strains lacking tap did not show chemotaxis toward thymine or uracil, while all tested strains with an intact tap gene and at least one high-abundance MCP (Tar or Tsr) showed taxis toward thymine and uracil. These results indicate that Tap, which is known to be involved in dipeptide chemotaxis (32), plays an essential role in chemotaxis to pyrimidines.

TABLE 2.

Qualitative capillary assay results with E. coli wild type and MCP deletion mutants

| Chemical stimulus (concn) | RP437 (wild-type) response | Mutant (deletion) chemotaxis response

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP1131 (Δtrg) | RP2361 (Δtar) | RP3525 (Δtap) | RP5700 (Δtsr ) | UU1250 (Δ[tar-tap] ΔtsrΔtrg ) | UU1615 (Δ[tar−tap]Δtrg) | UU1624 (Δtsr Δtrg Δtap) | UU1625 (Δtsr Δtrg ) | ||

| None (buffer only) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CAA (2%)a | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Aspartate (10−3 M) | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| Thymine (2 × 10−2 M) | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Uracil (2 × 10−2 M) | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + |

CAA, Casamino Acids was used as the positive control in these assays.

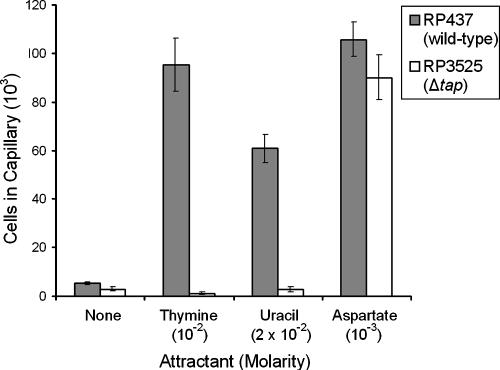

Using quantitative capillary assays, the responses of the Δtap mutant strain RP3525 to thymine and uracil were determined. The peak attractant concentrations determined with the wild-type strain RP437 (Fig. 1) were used for each pyrimidine. RP3525 cells did not respond to either pyrimidine but were still attracted to aspartate (Fig. 3). These results further confirm that Tap is required for pyrimidine chemotaxis.

FIG. 3.

Chemotactic responses of E. coli RP437 (wild type) and RP3525 (Δtap) to thymine and uracil. Cells were grown as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Results are the averages of at least 10 capillaries from at least three independent experiments; error bars indicate standard errors. “None” indicates that capillaries contained chemotaxis buffer only.

Chimeric MCP Tapsr is able to mediate pyrimidine chemotaxis.

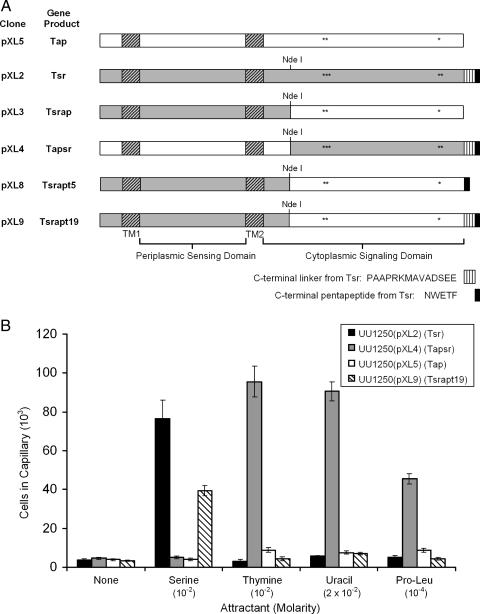

Chimeric MCPs were constructed by genetically switching the periplasmic sensing domains and the cytoplasmic signaling domains of Tap and Tsr, effectively fusing the N- and C-terminal domains of the two proteins at a site located 42 amino acids downstream of the second TM domain (Fig. 4A). This site corresponds to a conserved NdeI site present in tsr and tar, which has been used to construct Tap-Tar and Trg-Tsr hybrids (15, 43). The chimeric protein containing the periplasmic domain and both TM segments of Tap fused to the cytoplasmic portion of Tsr was designated Tapsr; the reciprocal fusion protein was designated Tsrap. Tsrapt5 and Tsrapt19 are derivatives of Tsrap, with the last 5 and 19 amino acids from Tsr, respectively, added to the C-terminal end to provide the essential C-terminal pentapeptide required for efficient signaling (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Chemotaxis of E. coli strains expressing wild-type or chimeric MCPs. (A) Diagram of wild-type and chimeric chemoreceptors expressed from the pXL2, pXL3, pXL4, pXL5, pXL8, and pXL9 derivatives of pRR48. Regions originating from Tap are in white; those from Tsr are in gray. Transmembrane regions (TM1 and TM2) are indicated by diagonally striped rectangles. The C-terminal linker region of Tsr, which is required for clustering at cell poles (30), is indicated by vertical stripes. The C-terminal pentapeptide NWTEF (from Tsr), which is required for binding CheR and CheB (8, 44), is indicated in black. Known or predicted methylation sites in Tsr and Tap are indicated by asterisks. (B) Quantitative chemotactic responses of UU1250(pXL2) (Tsr), UU1250(pXL4) (Tapsr), UU1250(pXL5) (Tap), and UU1250(pXL9) (Tsrapt19) to serine, thymine, uracil, and Pro-Leu. No responses to any of the tested attractants were detected with UU1250(pXL3) (Tsrap) or UU1250(pXL8) (Tsrapt5). Cells were grown at 30°C in H1 minimal salts medium containing 25 mM glycerol, the required amino acids, thiamine, and ampicillin and were induced with IPTG. Results are the averages of at least 10 capillaries from at least three independent experiments; error bars indicate standard errors. “None” indicates that capillaries contained chemotaxis buffer only.

Wild-type and chimeric MCP genes were expressed individually from the multicopy vector pRR48 in UU1250, an E. coli strain lacking all four of the native MCPs (Table 1). Chemotactic responses were measured after induction with IPTG, using quantitative capillary assays (Fig. 4B). As expected, UU1250(pXL2) (Tsr+) was attracted to serine but not to pyrimidines or the dipeptide l-prolyl-l-leucine (Pro-Leu). UU1250(pXL5), expressing wild-type Tap, did not respond to any of the tested compounds. The strain expressing Tapsr (UU1250[pXL4]) responded to thymine, uracil, and Pro-Leu but not to serine (Fig. 4B). Cells of UU1250(pXL3), expressing the chimeric MCP Tsrap, did not accumulate above background levels (approximately 4 × 103 cells/capillary) in any attractant-containing capillary. UU1250(pXL9), expressing Tsrapt19, was attracted to serine but not to thymine, uracil, or Pro-Leu (Fig. 4B). We also generated a chimeric version of Tsrap with the pentapeptide NWETF at the C terminus (Tsrapt5) (Table 1 and Fig. 4A) and found that this MCP did not confer UU1250 with the ability to respond to serine in qualitative capillary assays (data not shown), indicating that more than the C-terminal pentapeptide is required to confer signaling. None of the strains responded to any of the chemoattractants when they were grown in the absence of IPTG (data not shown). The results indicate that the periplasmic domain of Tap is responsible for detecting thymine and uracil and that the Tsr signaling domain confers on Tapsr the ability to mediate efficient chemotaxis.

Periplasmic DBP is not required for pyrimidine chemotaxis.

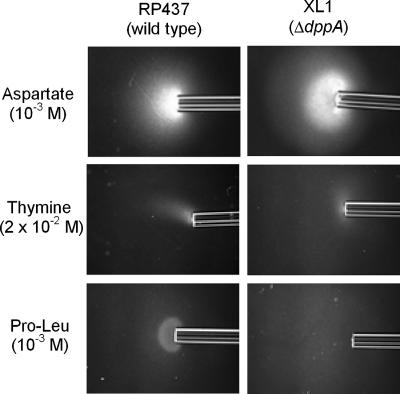

In E. coli, chemotaxis to dipeptides is mediated by Tap, but the primary chemoreceptor is the periplasmic binding protein for the transport of dipeptides, which is encoded by dppA (32). A ΔdppA mutant was constructed and tested with qualitative capillary assays to determine whether it was involved in the response to pyrimidines. The mutant showed wild-type responses to thymine and uracil as well as the expected defect in taxis to Pro-Leu (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Chemotactic phenotype of the E. coli ΔdppA mutant in modified capillary assays. Cells were grown as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Capillaries contained aspartate, thymine, or Pro-Leu at the indicated concentrations. Assays were carried out at room temperature for 20 min as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

Very little is known about chemotactic response to pyrimidines, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitative analysis of bacterial chemotaxis to pyrimidine bases. The nucleosides cytidine and uridine were tested as chemoattractants for E. coli B14 in capillary assays, but no response was detected; pyrimidines were apparently not tested in this study (3). Another study tested the chemotactic responses of Vibrio fischeri, a luminescent marine bacterium that forms a symbiotic association with the Hawaiian squid Euprymna scolopes. Using swarm plate assays to monitor the perturbation of serine swarm rings, DeLoney-Marino et al. demonstrated that V. fischeri responded to the pyrimidine nucleosides thymidine, cytidine, and uridine (14). In addition, V. fischeri clearly responded to deoxynucleoside triphosphates. The organism also appeared to respond very weakly to relatively high concentrations (≥66 mM) of thymine and uracil and therefore demonstrated a preference for nucleosides and nucleotides over the pyrimidine bases. The authors proposed that the response to components of DNA and RNA could play a role in the ability of V. fischeri to colonize its host, particularly in light of the fact that apoptosis of cells in the light organ of E. scolopes occurs during colonization (17). The chemoreceptor(s) involved in these responses was not identified.

Until recently, E. coli K-12 was not known to grow with thymine or uracil as the nitrogen source, but a study published in 2006 reported that the K-12 derivative NCM3876 utilizes both of the pyrimidines as the sole nitrogen sources via a new pathway at room temperature but not at 37°C (29). We found a similar pattern of temperature-sensitive growth with thymine and uracil for E. coli RP437, the standard strain used for studying chemotaxis, and demonstrated that RP437 is chemotactic to thymine and uracil at room temperature (Fig. 2) and at 30°C (Fig. 1). Although the genes required for pyrimidine utilization (rutABCDEFG) were shown to be expressed at higher levels under nitrogen-limiting conditions (29), the chemotactic response to pyrimidines appeared to be constitutive in strain RP437. Pyrimidine utilization at relatively low temperatures suggests that these compounds are used as nitrogen sources during that portion of the E. coli life cycle which occurs outside the animal host. The chemotactic responses observed within the same temperature range are consistent with the possibility that E. coli uses its pyrimidine chemotaxis system to locate alternative nitrogen sources when it is in the free-living state. Interestingly, most uropathogenic isolates of E. coli that were tested lacked both the trg and the tap genes, suggesting a difference in their selective environments (25). The thresholds for detection of thymine and uracil are relatively high, and it is not clear at this time whether the chemotactic response is physiologically relevant. Pyrimidines have been detected in soil samples, but concentrations were not reported (38); however, one could image the presence of relatively high concentrations of pyrimidines, for example, in rotting vegetation, where cells are lysing, and RNA and DNA are being released and degraded.

Slocum and Parkinson (39) reported the characterization of E. coli strains with tap deletions but were unable to identify a mutant phenotype. They did, however, make the insightful suggestion that Tap might be responsible for the detection of untested types of compounds such as peptides, vitamins, or nucleotides. A role for Tap was reported a year later when Manson et al. (32) demonstrated that Tap functions as the signal transducer for chemotactic responses to dipeptides. The current report reveals that a second set of chemoattractants, the pyrimidines thymine and uracil, requires the participation of Tap.

MCPs form clusters at cell poles (31) and signal collaboratively (5). The two high-abundance MCPs Tar and Tsr are present at cellular levels approximately 10-fold higher than those of the low-abundance MCPs Trg and Tap (21, 27). The pentapeptide NWETF, present at the C terminus of high-abundance MCPs, has been found to be the binding site for both CheR and CheB (8, 44) and is required for effective adaptation (35). Low-abundance MCPs lack this pentapeptide and are methylated and demethylated inefficiently in the absence of high-abundance MCPs. For this reason, cells containing only low-abundance receptors have strong counterclockwise flagellar rotational biases and do not respond well to gradients (15, 16, 43). Tap is a low-abundance MCP lacking the C-terminal ∼20 amino acid residues that are required for efficient signaling and as a result, strains expressing Tap as the sole MCP do not show chemotactic responses (Fig. 4B) (43). To confirm that Tap was responsible for mediating pyrimidine chemotaxis and to test whether pyrimidines are sensed through the periplasmic domain of Tap, we constructed hybrid Tap-Tsr MCPs. Functional Tap-Tar and Trg-Tsr hybrids have been constructed and analyzed previously (15, 16, 43). In each case, a hybrid MCP with the N-terminal sensing domain of a low-abundance MCP (Tap or Trg) fused to the C-terminal signaling domain of a high-abundance MCP (Tar or Tsr) was able to sense the compound(s) detected by the low-abundance MCP. For example, the Tap-Tar hybrid (designated Tapr) detected dipeptides but not aspartate (the attractant sensed by Tar) (43), and Trsr (the Trg-Tsr hybrid) responded to ribose and galactose (the attractants sensed by Trg) but did not sense serine (15, 16). All of our results (Fig. 4B) indicate that the periplasmic domain of Tap is responsible for sensing thymine and uracil and that the Tsr signaling domain confers on Tapsr the ability to mediate efficient chemotaxis. Interestingly, the addition of the C-terminal 23 amino acids from Tar onto Tap (Tapl) was insufficient to confer signaling ability on this chimeric MCP (43). In contrast, we found that the C-terminal 19 amino acids of Tsr were sufficient to allow signaling by the chimeric Tsrapt19. Whether the differences in signaling capacities between Tapl and Tsrapt19 are due to differences in the C-terminal sequences of Tar and Tsr or the fact that our chimeric protein contained both the N terminus and the extreme C terminus of Tsr is not clear at this time. However, we did find that the addition of only the terminal pentapeptide NWETF onto Tsrap resulted in a nonfunctional MCP, suggesting that the C-terminal linker upstream of the pentapeptide is essential. These results are consistent with reports demonstrating that the C-terminal ∼20 amino acids of high-abundance chemoreceptors are required for chemoreceptor clustering (30) and that the C-terminal linker upstream of the pentapeptide is important for adaptational modification (28).

In E. coli, amino acid attractants bind directly to MCPs, whereas sugars and dipeptides form complexes with specific periplasmic binding proteins, which then interact with the appropriate MCPs. The periplasmic DBP component of the dipeptide permease, which transports a variety of di- and tripeptides (1), was shown to be required for dipeptide chemotaxis (32). DBP functions as a high-affinity binding protein that interacts with Tap when bound to dipeptide substrates, and it is the only known periplasmic chemoreceptor for nonsugar substrates (32). Although we considered it unlikely that DBP would be involved in taxis to pyrimidines, we decided it was worth testing because prior to the current study, dipeptides were the only chemoattractants identified that were sensed through Tap. Using a ΔdppA mutant, we showed that DBP is not required for pyrimidine chemotaxis because the mutant still responded to thymine and uracil (Fig. 5). At this time, we do not know whether Tap serves as the primary chemoreceptor for pyrimidines, but if a periplasmic binding protein is not involved, pyrimidines would be the first attractants that interact directly with Tap. Periplasmic binding proteins that are known to be involved in chemotaxis are typically components of ABC transporters. Although there are currently no ABC transporters identified for pyrimidines in E. coli, there are several annotated ABC transporter gene clusters in the E. coli genome for which substrates remain unidentified. The known pyrimidine transporters in E. coli include the membrane-bound cytosine and uracil transporters CodB and UraA (6, 11), both of which have 12 predicted membrane-spanning segments (6, 10). In addition, RutG, which is encoded in the pyrimidine utilization gene cluster, has recently been predicted to be a uracil permease with 11 membrane-spanning segments (29). There are currently two examples of membrane-bound major facilitator superfamily transporters that are also required for chemotaxis to their substrates. These include PcaK, the transporter/receptor for 4-hydroxybenzoate in Pseudomonas putida PRS2000 (19, 34), and TfdK, the transporter/receptor for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate in Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 (20, 26). The specific roles of these two proteins in chemotaxis are not completely clear, but each is absolutely required for the chemotactic response. Future work will be required to address the question of whether Tap binds pyrimidines directly or via an additional chemoreceptor protein.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandy Parkinson for providing strains, numerous valuable suggestions, and constructive comments on the manuscript. We thank Valley Stewart and Li-Ling Chen for providing strains and for helpful advice on the construction of the ΔdppA mutant; Carrie Harwood, Eric Kofoid, Sydney Kustu, Jack Meeks, and Michele Igo for helpful discussions; and several attendees of the BLAST meeting and two anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions.

This work was supported by a University of California Toxic Substances Research and Teaching Program Investigator grant.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abouhamad, W. N., M. Manson, M. M. Gibson, and C. F. Higgins. 1991. Peptide transport and chemotaxis in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: characterization of the dipeptide permease (Dpp) and the dipeptide-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 51035-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler, J. 1973. A method for measuring chemotaxis and use of the method to determine optimum conditions for chemotaxis by Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 7477-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler, J., G. L. Hazelbauer, and M. M. Dahl. 1973. Chemotaxis toward sugars in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 115824-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ames, P., and J. S. Parkinson. 2006. Conformational suppression of inter-receptor signaling defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1039292-9297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ames, P., C. A. Studdert, R. H. Reiser, and J. S. Parkinson. 2002. Collaborative signaling by mixed chemoreceptor teams in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 997060-7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderssen, P. S., D. Frees, R. Fast, and B. Mygind. 1995. Uracil uptake in Escherichia coli K-12: isolation of uraA mutants and cloning the gene. J. Bacteriol. 1772008-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker, M. D., P. M. Wolanin, and J. B. Stock. 2006. Signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis. Bioessays 289-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnakov, A. N., L. A. Barnakova, and G. L. Hazelbauer. 1999. Efficient adaptational demethylation of chemoreceptors requires the same enzyme-docking site as efficient methylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9610667-10672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bibikov, S. I., A. C. Miller, K. K. Gosink, and J. S. Parkinson. 2004. Methylation-independent aerotaxis mediated by the Escherichia coli Aer protein. J. Bacteriol. 1863730-3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danielsen, S., D. Boyd, and J. Neuhard. 1995. Membrane topology analysis of the Escherichia coli cytosine permease. Microbiology 1412905-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danielsen, S., M. Kilstrup, K. Barilla, B. Jochimsen, and J. Neuhard. 1992. Characterization of the Escherichia coli codBA operon encoding cytosine permease and cytosine deaminase. Mol. Microbiol. 61335-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 976640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis, R. W., D. Botstein, and J. R. Roth. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 14.DeLoney-Marino, C. R., A. J. Wolfe, and K. L. Visick. 2003. Chemoattraction of Vibrio fischeri to serine, nucleosides, and N-acetylneuraminic acid, a component of squid light-organ mucus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 697527-7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng, X., J. W. Baumgartner, and G. L. Hazelbauer. 1997. High- and low-abundance chemoreceptors in Escherichia coli: differential activities associated with closely related cytoplasmic domains. J. Bacteriol. 1796714-6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng, X., A. A. Lilly, and G. L. Hazelbauer. 1999. Enhanced function conferred on low-abundance chemoreceptor Trg by a methyltransferase-docking site. J. Bacteriol. 1813164-3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster, J. S., and M. J. McFall-Ngai. 1998. Induction of apoptosis by cooperative bacteria in the morphogenesis of host epithelial tissues. Dev. Genes Evol. 208295-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimm, A. C., and C. S. Harwood. 1997. Chemotaxis of Pseudomonas putida to the polyaromatic hydrocarbon naphthalene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 634111-4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harwood, C. S., N. N. Nichols, M.-K. Kim, J. L. Ditty, and R. E. Parales. 1994. Identification of the pcaRKF gene cluster from Pseudomonas putida: involvement in chemotaxis, biodegradation, and transport of 4-hydroxybenzoate. J. Bacteriol. 1766479-6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkins, A. C., and C. S. Harwood. 2002. Chemotaxis of Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4) to the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68968-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazelbauer, G. L., P. Engstrom, and S. Harayama. 1981. Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein III and transducer gene trg. J. Bacteriol. 14543-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedblom, M. L., and J. Adler. 1980. Genetic and biochemical properties of Escherichia coli mutants with defects in serine chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 1441048-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondoh, H., C. B. Ball, and J. Adler. 1979. Identification of a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein for the ribose and galactose chemoreceptors of Escherichia coli Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76260-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kustu, S., D. Burton, E. Garcia, L. McCarter, and N. McFarland. 1979. Nitrogen control in Salmonella: regulation by the glnR and glnF gene products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 764576-4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lane, M. C., A. L. Lloyd, T. A. Markyvech, E. C. Hagan, and H. L. Mobley. 2006. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains generally lack functional Trg and Tap chemoreceptors found in the majority of E. coli strains strictly residing in the gut. J. Bacteriol. 1885618-5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leveau, J. H., A. J. Zehnder, and J. R. van der Meer. 1998. The tfdK gene product facilitates uptake of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate by Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4). J. Bacteriol. 1802237-2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, M., and G. L. Hazelbauer. 2004. Cellular stoichiometry of the components of the chemotaxis signaling complex. J. Bacteriol. 1863687-3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, M., and G. L. Hazelbauer. 2006. The carboxyl-terminal linker is important for chemoreceptor function. Mol. Microbiol. 60469-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loh, K. D., P. Gyaneshwar, E. Papadimitriou, R. Fong, K.-S. Kim, R. E. Parales, Z. Zhou, W. Inwood, and S. Kustu. 2006. A previously undescribed pathway for pyrimidine catabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1035114-5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lybarger, S. R., U. Nair, A. A. Lilly, G. L. Hazelbauer, and J. R. Maddock. 2005. Clustering requires modified methyl-accepting sites in low-abundance but not high-abundance chemoreceptors of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 561078-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddock, J. R., and L. Shapiro. 1993. Polar location of the chemoreceptor complex in the Escherichia coli cell. Science 2591717-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manson, M. D., V. Blank, G. Brade, and C. F. Higgins. 1986. Peptide chemotaxis in E. coli involves the Tap signal transducer and the dipeptide permease. Nature 321253-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer, G., T. Schneider-Merck, S. Bohme, and W. Sand. 2002. A simple method for investigations on the chemotaxis of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and Desulfovibrio vulgaris. Acta Biotechnol. 22391-399. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nichols, N. N., and C. S. Harwood. 1997. PcaK, a high-affinity permease for the aromatic compounds 4-hydroxybenzoate and protocatechuate from Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 1795056-5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okumura, H., S. Nishiyama, A. Sasaki, M. Homma, and I. Kawagishi. 1998. Chemotactic adaptation is altered by changes in the carboxy-terminal sequence conserved among the major methyl-accepting chemoreceptors. J. Bacteriol. 1801862-1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parkinson, J. S., P. Ames, and C. A. Studdert. 2005. Collaborative signaling by bacterial chemoreceptors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8116-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parkinson, J. S., and S. E. Houts. 1982. Isolation and behavior of Escherichia coli deletion mutants lacking chemotaxis functions. J. Bacteriol. 151106-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schreiner, O., and E. C. Shorey. 1910. Pyrimidine derivatives and purine bases in soils. J. Biol. Chem. 8385-393. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slocum, M. K., and J. S. Parkinson. 1985. Genetics of methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins in Escherichia coli: null phenotypes of the tar and tap genes. J. Bacteriol. 163586-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sourjik, V. 2004. Receptor clustering and signal processing in E. coli chemotaxis. Trends Microbiol. 12569-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Springer, M. S., M. F. Goy, and J. Adler. 1977. Sensory transduction in Escherichia coli: two complementary pathways of information processing that involve methylated proteins Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 743312-3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Studdert, C. A., and J. S. Parkinson. 2005. Insights into the organization and dynamics of bacterial chemoreceptor clusters through in vivo crosslinking studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10215623-15628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weerasuriya, S., B. M. Schneider, and M. D. Manson. 1998. Chimeric chemoreceptors in Escherichia coli: signaling properties of Tar-Tap and Tap-Tar hybrids. J. Bacteriol. 180914-920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu, J., J. Li, G. Li, D. G. Long, and R. M. Weis. 1996. The receptor binding site for the methyltransferase of bacterial chemotaxis is distinct from the sites of methylation. Biochemistry 354984-4993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhulin, I. B. 2001. The superfamily of chemotaxis transducers: from physiology to genomics and back. Adv. Microbial Phys. 45157-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]