Abstract

Porphyromonas gingivalis, a gram-negative anaerobe which is implicated in the etiology of active periodontitis, secretes degradative enzymes (gingipains) and sheds proinflammatory mediators (e.g., lipopolysaccharides [LPS]). LPS triggers the secretion of interleukin-8 (IL-8) from immune (72-amino-acid [aa] variant [IL-872aa]) and nonimmune (IL-877aa) cells. IL-877aa has low chemotactic and respiratory burst-inducing activity but is susceptible to cleavage by gingipains. This study shows that both R- and K-gingipain treatments of IL-877aa significantly enhance burst activation by fMLP and chemotactic activity (P < 0.05) but decrease burst activation and chemotactic activity of IL-872aa toward neutrophil-like HL60 cells and primary neutrophils (P < 0.05). Using tandem mass spectrometry, we have demonstrated that R-gingipain cleaves 5- and 11-aa peptides from the N-terminal portion of IL-877aa and the resultant peptides are biologically active, while K-gingipain removes an 8-aa N-terminal peptide yielding a 69-aa isoform of IL-8 that shows enhanced biological activity. During periodontitis, secreted gingipains may differentially affect neutrophil chemotaxis and activation in response to IL-8 according to the cellular source of the chemokine.

Inflammatory periodontal diseases have an infectious etiology and are characterized by excess inflammation within the periodontal tissues, which can progress to alveolar bone loss and ultimately tooth loss (4). The primary etiological agent for periodontitis is the subgingival plaque biofilm, and disease progression is associated with an ecological shift in biofilm composition to a predominantly anaerobic flora (5, 27). Evidence indicates that this in turn triggers the host response, which in susceptible patients is abnormal, involving excess generation of proteolytic enzymes (9) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (18), both of which are important determinants of disease progression and severity (5, 11). Neutrophilic inflammation is the major source of the tissue-destructive species (6), and recent studies have demonstrated that peripheral blood neutrophils from periodontitis patients are both hyperreactive to Fcγ-receptor stimulation and also demonstrate baseline hyperactivity with respect to extracellular ROS release (17, 18). The extracellular ROS production from neutrophil infiltrates into the periodontium is significant (17) but modest; however, any process which results in enhanced polymorphonuclear leukocyte recruitment to or retention (e.g., delayed apoptosis) within the periodontal tissues may contribute to ROS-mediated tissue damage.

The oral anaerobic rod Porphyromonas gingivalis is the organism most strongly associated with active periodontitis (1). This organism possesses a number of virulence determinants which potentially contribute to its pathogenicity, including the ability to secrete a range of degradative proteinases (1); among these, the gingipains have been extensively studied (15). Furthermore, the pathogenic bacteria within the subgingival environment shed proinflammatory mediators such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS in turn triggers the secretion of chemokines/cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-6 and IL-8 (72-amino-acid [aa] variant [IL-872aa]) from resident inflammatory cells, which contribute to the initial inflammatory response (20).

IL-8 is a major chemokine with potent stimulatory effects on neutrophils, including chemotaxis, degranulation, and cytoplasmic Ca2+ elevation. IL-8 is a small polypeptide with a molecular mass of 8 to 10 kDa (22) that was originally isolated from monocytes (2). Subsequent studies have shown that IL-8 is also produced from a wide range of cell types, including fibroblasts, epithelial cells/keratinocytes, lymphocytes, endothelial cells, and neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils). In response to stimulus, IL-8 is produced as a 99-aa-long precursor polypeptide (2), which is subsequently processed into a biologically active peptide. IL-8 varies in length from 79 aa to 77-, 72-, 71-, 70-, and 69-aa variants (23). Although IL-8 is subject to variable processing at the N terminus, the IL-872aa and IL-877aa peptides have been identified as the predominant variants. The major form of IL-872aa has been extensively studied for its potent ability to prime neutrophils to stimulate the respiratory burst to a secondary stimulus, such as N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) (12, 14).

IL-877aa is recognized as a less-potent variant for neutrophil activation. It exhibits reduced chemotactic properties and attenuates neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cell walls (10). Recent reports have suggested that this longer-amino-acid form is susceptible to cleavage by proteolysis into a biologically active form (13, 24, 25). It has also been shown that IL-877aa is susceptible to cleavage by gingipains, the principal secreted cysteine proteases of P. gingivalis (19). The potential for gingipains to enhance the activity of IL-877aa presents an additional mechanism of the organism's pathogenicity, whereby P. gingivalis promotes enhanced neutrophil recruitment, activation, and further local tissue degradation. To date, the effect of gingipain processing of IL-8 on subsequent chemotactic activity or respiratory burst priming has not been determined. Therefore, this report investigates whether gingipains from P. gingivalis can modify IL-877aa chemotactic and priming activities using primary neutrophils and differentiated cells (dHL60) of the neutrophil-like HL60 cell line as responder cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

P. gingivalis W83 was kindly provided by A. Roberts (Periodontal Research Group, School of Dentistry, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom). All reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (Poole, United Kingdom) and solvents from Fisher (Loughborough, United Kingdom) unless otherwise stated. RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum, and penicillin (1,000 U ml−1)/streptomycin (10,000 μg ml−1) were obtained from GibcoBRL (Paisley, United Kingdom). Recombinant IL-872aa, endothelium-derived recombinant IL-877aa, and monoclonal anti-human IL-8 antibody, clone 6218, were purchased from R&D systems (Abingdon, United Kingdom).

HL60 cell cultures.

The human promyelocytic cell line HL60 was purchased from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC no. 98070101) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2-95% air humidified atmosphere. The cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of 1.0% dimethyl sulfoxide for 5 days after seeding at cell density of 2 × 105 cells/ml.

Collection and isolation of peripheral blood neutrophils.

Venous blood was collected from systemically and periodontally healthy donors into 4% sodium citrate (wt/vol) in phosphate-buffered saline, with a citrate/blood ratio of 1:9, and neutrophils were isolated as described by Matthews et al. (7). Isolated cells were washed and resuspended in physiological salt solution (PSS: 115 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 25 mM HEPES-Na supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin at pH 7.4).

Cultivation of P. gingivalis strain W83.

Cultures were grown statically in 200 ml of liquid medium containing 6.0g of Trypticase soy broth (Difco, Detroit, MI), 2.0 g of yeast extract, supplemented with 1 mg of hemin, 200 mg of l-cysteine, 20 mg of dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mg of menadione at 37°C in an anaerobic atmosphere of 10% H2, 10% CO2, and 80% N2 for 48 h (miniMACS anaerobic workstation; Don Whitley Scientific).

Isolation of Rgp and Kgp.

Gingipains were isolated according to the method described by Yun et al. (29) using a 5-ml packed-volume arginine-Sepharose column for the final affinity purification stage. Column fractions (1 ml) containing lysine-specific gingipain (Kgp; eluted with 0.75 M l-lysine) and arginine-specific gingipain (Rgp; eluted with 1 M l-arginine) were dialyzed against Tris buffer overnight at 5°C.

Enzyme activity assays.

The amidolytic activities of the purified Rgp and Kgp were measured with the substrate α-N-benzoyl-l-arginine p-nitroanilide hydrochloride (l-BAPNA). One hundred microliters of each of the Rgp and Kgp fractions was incubated with l-BAPNA (final concentration of 1 mM) in 100 μl of 0.2 M Tris-HCl, 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM l-cysteine at pH 7.6 and 37°C. After 1 h of incubation, the reaction was stopped by addition of 10 μl of glacial acetic acid. The optical density was measured at 405 nm for each fraction, and the values were corrected by subtraction of negative control values (without proteinases).

Proteolytic degradation of IL-8 by purified gingipains.

Pooled fractions for each gingipain were activated as described by Mikolajczyk-Pawlinska et al. (18). Rgp and Kgp were adjusted to equimolar concentrations in Tris buffer, pH 7.6. Activated gingipains (3 mM) were mixed with 1.65 μM IL-877aa or IL-872aa and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Enzyme activity was terminated postincubation by addition of 1 μl of a protease inhibitor cocktail containing leupeptin hemisulfate.

MS/MS analysis of Kgp- and Rgp-treated IL-877aa and IL-872aa.

Kgp- or Rgp-treated IL-877aa and IL-872aa (0.14 pg/μl) were diluted in 50% methanol in water with acetic acid (1%) to enhance ionization and subjected to mass analysis after injection at 1 μl/min using a Thermo LTQ tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS) in electrospray mode. The machine was externally mass calibrated using peptides, caffeine, and Ultramark 1621 (ABCR GmbH & Co.). The acceleration voltage was set at 20 kV, and data were collected as the average total scan of 100 scans with the scan range set from 100 to 2,000 m/z to search for fragmented IL-877aa and IL-872aa. Multiply charged molecular ions were subjected to collision-induced dissociation (CID) with argon gas, and the resulting MS/MS data were recorded for comparison against SWISSPROT predicted cleavage sites in IL-8.

Neutralization of IL-877aa peptide chemotactic activity.

In order to investigate whether the enhanced biological activity of Kgp- or Rgp-treated IL-8 could be ascribed to the resultant formation of IL-872aa rather than to the released peptides, neutralizing anti-human IL-8 antibody (5 μg/ml), which recognizes the whole molecule, was added to Kgp- or Rgp-treated IL-877aa (8.25 nM) for 30 min at room temperature prior to addition of neutralized IL-8 to the lower chambers for chemotaxis experiments.

Chemotaxis assay.

dHL60 cell/neutrophil chemotaxis was measured by Boyden's technique using (2- or 5-μm pore size, respectively) polyvinylpyrrolidone-free polycarbonate filters in a 96 multiwell chamber (Neuroprobe, Inc.). dHL60 cells/neutrophils (1 × 105) were washed and resuspended in PSS. Pre- and post-gingipain-treated IL-8 (8.25 nM) samples, gingipain-treated and antibody-neutralized IL-877aa, and untreated gingipains were added to the lower wells of the chamber, the filter was fixed in place, and the upper wells were loaded with 1 × 105 dHL60 cells/neutrophils in 100 μl of PSS at 37°C for 90 min. After chemotaxis, cell-containing buffer from the upper chamber was removed and the top of the filter was washed with PSS. The microplate/filter assembly was centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min. The filter was carefully removed, and cell counts in the lower chamber were taken by flow cytometry (Coulter Epics XL). Results were expressed as specific cell migration after subtraction of background migration. Escherichia coli LPS (serotype 0111:B4; 1 μg/ml) was used as a positive control in all assays, and Rgp and Kgp alone in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail acted as a negative control.

Chemiluminescent assay for respiratory burst activity.

Chemiluminescence assays were performed using lucigenin to detect total superoxide production by neutrophils or dHL60 cells. Assays were performed (37°C) using a Berthold microplate luminometer (LB96v). Neutrophils (5 ×105 cells) were added to each well containing 100 μM lucigenin in PSS and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Light emission in relative light units (RLU) was recorded during the 30-min prestimulation period to establish a steady baseline. Cells were then incubated with gingipain-treated or untreated IL-8 isoforms for 10 min prior to stimulation with 1 μM fMLP. The RLU peak values were analyzed for each treatment, and time to peak for each stimulus was recorded.

Data analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's comparison test analysis. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

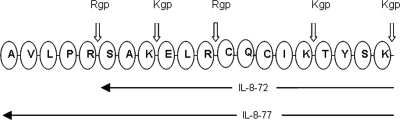

Kgp and Rgp specifically cleave the N terminus of IL-877aa.

Rgp has two theoretical, amino peptidase cleavage sites for IL-877aa, and Kgp has three amino peptidase cleavage sites in IL-877aa (Fig. 1). At the N terminus of IL-872aa, Rgp has one theoretical cleavage site, while Kgp has three sites. To investigate the effects of gingipain activity on IL-877aa, released N-terminal peptides corresponding in mass to Rgp- and Kgp-cleaved IL-877aa isoforms were investigated by MS/MS with CID. Rgp treatments preferentially cleaved the N terminus of IL-877aa, releasing peptides of m/z 555.7 and 703.82 corresponding to residues 1 to 5 and 6 to 11 of the N-terminal region with the sequences reported in Table 1, to produce 72- and 66-aa-long IL-8 peptides. Rgp treatment also released a peptide of m/z 703.41 and sequence SAKELR from IL-872aa to yield an IL-866aa polypeptide. However, Kgp treatment of IL-877aa released an 8-aa-long polypeptide of m/z 842.03 (AVLPRSAK) from the N terminus, resulting in a 69-aa-long IL-8 polypeptide. Kgp treatment of IL-872aa released peptides of m/z 305.18, 1135.4, and 498.5, resulting in 69-, 61-, and 57-aa-long peptides, respectively.

FIG. 1.

N-terminal amino acid sequence of IL-8 and possible Rgp and Kgp cleavage sites. IL-877aa (IL-8-77) has a peptide sequence extended by 5 aa relative to IL-872aa (IL-8-72). Rgp has specific amino peptidase activity to R-X peptide bonds, and Kgp has specific amino peptidase activity to K-X peptide bonds.

TABLE 1.

Release of amino-terminal peptides by gingipain treatment of IL-877aa and IL-872aa as determined by MS/MSa

| IL-8 isoform and gingipain treatment | m/z | aa position

|

Sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | |||

| IL-877aa | ||||

| Rgp | 555.7020 | 1 | 5 | AVLPR |

| 703.8212 | 6 | 11 | SAKELR | |

| Kgp | 842.0352 | 1 | 8 | AVLPRSAK |

| IL-872aa | ||||

| Rgp | 703.4097 | 1 | 6 | SAKELR |

| Kgp | 305.1819 | 1 | 3 | SAK |

| 1135.4 | 4 | 11 | ELRCQCIK | |

| 498.5 | 12 | 15 | TYSK | |

The table documents m/z ratios, amino acid positions, and sequences of peptides released post-Kgp treatment of IL-877aa.

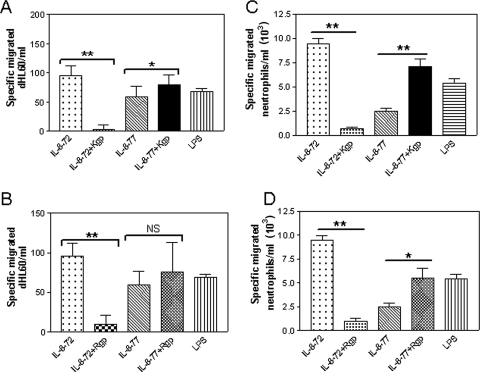

Kgp and Rgp increase the chemotactic properties of biologically inactive IL-877aa.

In order to determine the effect of Rgp and Kgp treatment on chemotactic properties of IL-8 isoforms, dHL60 cells/primary neutrophils were allowed to undergo chemotaxis toward pre- or post-gingipain-treated IL-872aa and IL-877aa isoforms. The effect of gingipain treatment on IL-8-dependent chemotaxis was corrected for chemotaxis toward either inactivated Rgp or inactivated Kgp, where migration was always lower toward gingipains than to LPS or IL-8 isoforms. IL-872aa demonstrated higher chemotactic activity than the native IL-877aa isoform. Both Rgp (Fig. 2A) and Kgp (Fig. 2B) treatments significantly decreased the chemotactic activity of IL-872aa (P < 0.001) toward HL60 cells. In contrast, Kgp treatment significantly increased IL-877aa chemotactic properties (P < 0.05). In order to compare the behavior of dHL60 cells with peripheral blood neutrophils, chemotaxis of primary neutrophils toward IL-8 isoforms was measured. Confirming the observations in dHL60 cells, both Kgp (Fig. 2C) and Rgp (Fig. 2D) treatments significantly increased the chemotactic properties of IL-877aa (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively) toward primary neutrophils.

FIG. 2.

Gingipain treatment increases chemotactic activity of IL-877aa toward dHL60 cells and neutrophils. IL-8 isoforms of 72- and 77-aa-long peptides (IL-8-72 and IL-8-77, respectively) were treated with 10 mM cysteine activated Kgp or Rgp for 30 min. Chemotaxis (corrected for background) of 1 × 105 dHL60 cells through a 2-μm filter toward Kgp (A)- and Rgp (B)-treated or untreated IL-8 isoforms was observed for 90 min in a multiwell chemotaxis chamber. Specific chemotaxis of 1 × 105 primary neutrophils toward Kgp (C)- and Rgp (D)-treated IL-8 isoforms through a 5-μm filter was observed for 90 min in a multiwell chemotaxis chamber. Cell counts in the lower wells were taken by flow cytometry and are expressed as mean cell number migrated ± standard error of the mean, where n = 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001; and NS, not significant by Tukey's multiple comparison test.

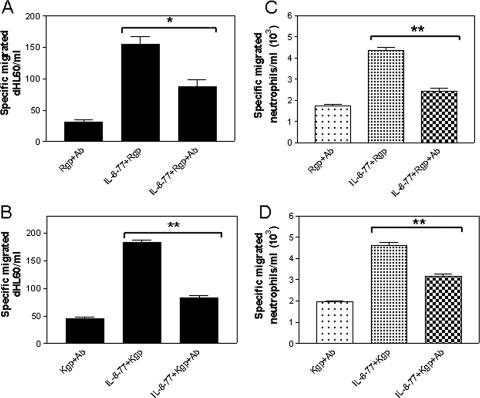

N-terminally shortened peptide fragments of IL-877aa account for the increased chemotactic activity.

To investigate whether N-terminally shortened IL-877aa peptides accounted for the observed chemotactic activity, gingipain-treated IL-877aa was neutralized with anti-human IL-8 antibody prior to chemotaxis assay. Both antibody-neutralized Rgp-treated IL-877aa (Fig. 3A) and Kgp-treated IL-877aa (Fig. 3B) showed significantly decreased chemotactic activity toward dHL60 cells (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) compared with gingipain-treated IL-877aa in the absence of neutralizing antibody. Similarly, when the experiment was repeated using neutralized Kgp- or Rgp-treated IL-877aa as a chemotaxin for primary neutrophils, again, the enhanced biological activity of gingipain-cleaved IL-877aa was not evident (Fig. 3C and D).

FIG. 3.

Major IL-8 peptides released from gingipain treatment of IL-877aa are responsible for enhanced chemotactic activity of dHL60 cells and primary neutrophils. IL-8 isoforms of 72- and 77-aa-long peptides (IL-8-72 and IL-8-77, respectively) were treated with 10 mM cysteine-activated Kgp or Rgp for 30 min. After neutralization of gingipains, the resultant peptides were subsequently incubated with neutralizing anti-IL-8 antibody (Ab). Chemotaxis (corrected for background) of 1 × 105 dHL60 cells through a 2-μm filter toward Kgp-treated IL-877aa and Kgp-treated IL-877aa plus IL-8-neutralized isoforms (A) or Rgp-treated IL-877aa and Rgp-treated IL-877aa plus IL-8-neutralized isoforms (B) was observed for 90 min in a multiwell chemotaxis chamber. Specific chemotaxis of 1 × 105 primary neutrophils toward Kgp-treated-IL-877aa and Kgp-treated IL-877aa plus IL-8-neutralized isoforms (C) and Rgp-treated-IL-877aa and Rgp-treated IL-877aa plus IL-8-neutralized isoforms (D) through a 5-μm filter was observed for 90 min in a multiwell chemotaxis chamber. Cell counts in the lower wells were taken by flow cytometry and are expressed as mean cell number migrated ± standard error of the mean, where n = 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. **, P < 0.001 by Tukey's multiple-comparison test.

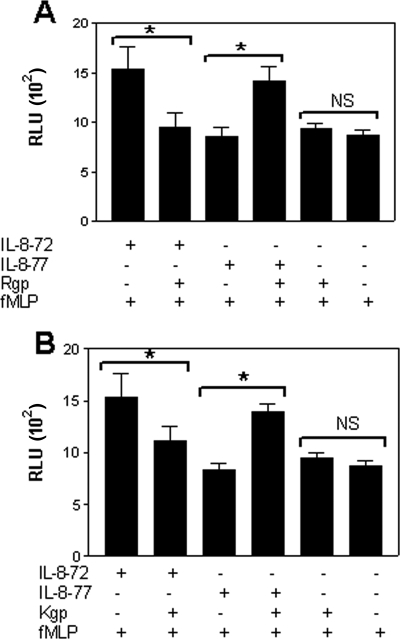

Kgp and Rgp increase the priming effect of IL-877aa for the respiratory burst in response to fMLP.

The priming effect of IL-8 on the fMLP-induced respiratory burst was measured by lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence using isolated peripheral blood neutrophils. IL-872aa primed neutrophils for enhanced superoxide production after fMLP stimulation, whereas neither IL-877aa nor isolated gingipains had any priming effect (Fig. 4). However, both Rgp (Fig. 4A)- and Kgp (Fig. 4B)-treated IL-877aa primed neutrophils for fMLP-induced superoxide production, demonstrating significantly increased superoxide generation compared with native IL-877aa (P < 0.05). In contrast, gingipain treatment decreased the priming activity of IL-872aa (P < 0.05) for fMLP-stimulated superoxide production.

FIG. 4.

Gingipain treatment enhances the priming effect of IL-877aa on neutrophils. Neutrophils (5 × 105) were primed with Rgp-treated or untreated 72- and 77-aa IL-8 isoforms (IL-8-72 and IL-8-77, respectively) (A) or Kgp-treated or untreated IL-8 isoforms (B) for 10 min prior to stimulation with 1 μM fMLP. Mean peak (RLU ± standard error of the mean; n = 9) chemiluminescence generated by neutrophils was recorded. Significant differences were calculated (*, P < 0.05) with Tukey's multiple-comparison test. NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

Infection of host tissue by pathogenic bacteria and/or stimulation by microbial components/virulence factors triggers the production of proinflammatory peptides that have the ability to activate and recruit neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes along a concentration gradient. Patients with periodontitis show increased numbers of neutrophils within periodontal tissues and pockets (21), and recent work has demonstrated baseline hyperactivity of peripheral blood neutrophils, with respect to extracellular ROS release (18) and proteolytic enzyme release (9), in periodontitis patients relative to matched healthy controls. Such mechanisms when coactive may explain a significant amount of the oxidative stress reported in periodontitis-affected tissues (6). Therefore, the influence of periodontal bacteria and their virulence factors on IL-8-mediated neutrophil chemotaxis and activation is important to elucidate. In contrast to biologically active IL-872aa, the IL-877aa peptide produced by epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells is resistant to a wide range of host proteinases; it has a low chemotactic activity (10) and less respiratory burst-priming activity. In our experiments, we have used LPS as a positive control; LPS is a well-known chemotactic bacterial component which requires serum components such as LPS-binding protein for receptor activation (28). However, as serum may also contain other chemotactic factors, it was excluded from our experiments, and the chemotactic activity of LPS in serum-free conditions here was greater than that of IL-877aa but less than that of IL-872aa toward primary neutrophils.

In this study, we have investigated a possible mechanism by which P. gingivalis could manipulate IL-8 cytokine-mediated neutrophil chemotaxis using a dHL60 cell model and also primary human neutrophils. Gingipains increased the priming activity induced by IL-877aa on the fMLP-induced oxidative burst in primary neutrophils, data that confirm previous studies measuring elastase release from neutrophils, where IL-877aa-induced release was shown to be increased after gingipain treatment (19).

Our results demonstrate a significant increase in the chemotactic properties of IL-877aa and a higher priming capability of IL-877aa after incubation with l-cysteine-activated gingipains under the conditions described. Compared with primary neutrophils, dHL60 cells have low CXC2 receptor expression (26), and this may explain the lower rate of dHL60 cell migration toward IL-8. The corresponding increase in data variation may account for the lack of significant increase in migration of dHL60 cells toward Rgp-treated IL-877aa compared to the increased migration of primary neutrophils. Chemotactic properties and priming abilities of truncated, gingipain-treated forms of IL-877aa were found to be two- to threefold higher than those of untreated IL-877aa. Using a neutralizing antibody against the complete sequence of IL-8, we confirmed that the increased biological activity of IL-877aa following gingipain treatment was due to the release of mature IL-8, rather than due to the release of small peptides identified by MS, as the neutralizing antibody (which does not recognize small peptide fragments) completely inhibited the increase in activity. Given that reported concentrations of reduced glutathione/cysteine in gingival fluids are 1,000-fold higher than those of serum (7), this may represent a physiologically relevant mechanism whereby gingipains contribute to neutrophil recruitment and activation at P. gingivalis-infected sites.

The extended amino terminus of IL-877aa folds back to interact with the essential Glu4-Leu5-Arg6 (ELR) sequence; this may protect the ELR sequence from interaction with the receptor and may explain the low chemotactic activity of IL-877aa compared to IL-872aa. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of IL-877aa is AVLPRSAKELRCQCIKTYSK- (21). Rgp has theoretical, specific amino peptidase cleavage activity at Arg5-Ser6 and Arg11-Cys12 (15), yielding peptides with lengths of 72 and 66 aa. After Rgp treatment, we observed cleavage products of IL-877aa by MS/MS of the 5 and 11 aa corresponding to the putative N-terminal cleavage sites. There was no evidence of low-molecular-weight peptides corresponding to cleavage at the putative C-terminal sites. Even though some reports suggest that ELR sequences in IL-8 are necessary for high-affinity binding to IL-8 receptor, recent studies have shown that IL-866aa has similar activity to IL-872aa (8). Our observations do not fully support the latter work: while an increase in activity of IL-877aa is observed after Rgp treatment, which results in products with lengths of 72 and 66 aa, a decrease in IL-872aa activity was observed after Rgp treatment, indicating that IL-866aa is not biologically active and that the observed increase in activity after treatment of IL-877aa with Rgp may be due to release of IL-872aa alone. Active IL-8 requires a properly folded protein structure with a highly conserved ELR sequence near the N terminus that is critical for its activity (16). Kgp, with its specificity for the Lys-X peptide bond, is predicted to cleave the IL-877aa amino-terminal sequence at Lys8-Glu9, and this product was observed in our studies by MS/MS. The resultant 69-aa-long form of IL-8 shows enhanced biological activity compared with IL-877aa in our studies of chemotactic activity and respiratory burst priming. In contrast, the more biologically active form of IL-872aa showed reduced chemotactic activity after treatment with both Rgp and Kgp. Analysis of released peptides by MS/MS confirmed further cleavage of IL-872aa, releasing three peptides corresponding to the 15 N-terminal aa of IL-872aa. The presence of 5 aa at the N terminus of IL-877aa compared to IL-872aa appears to modulate cleavage of the peptide by gingipains. The difference in IL-877aa susceptibility to gingipain treatment compared with that of IL-872aa may relate to either differences in three-dimensional structures at the N terminus or specific charge differences which contribute to change in altered accessibility and thus cleavage by gingipains. Previous studies have shown that prolonged incubation with Rgp or Kgp could result total IL-877aa degradation (19); physiologically, a concentration gradient will exist, where released gingipain will be highest in closest proximity to the site of bacterial colonization and via diffusion the concentration of gingipains will be lower further away from the site. Thus, while initial enzyme release may activate local IL-877aa in the early stages of infection, the IL-877aa variant may be completely degraded in the immediate locality over time. However, further from the site of infection, diffusing gingipain may cause activation of IL-877aa. The importance of this observation should be addressed in vivo following specific inhibition of gingipain activity or expression.

Previous studies have shown that the capacity of gingipains to manipulate the host cytokine network is partly due to degradation of other cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (3). Therefore, it has been suggested that the ability to inactivate cytokines by P. gingivalis in the early stages of pathogenesis is advantageous for the organism. Rgp has recently been shown to digest secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor released from neutrophils, thus reducing the protective effect against bacterial proinflammatory molecules by which disease in periodontal tissues may be accelerated (21). In contrast, degradation of proinflammatory cytokines could diminish neutrophil chemotaxis toward infected periodontal sites by lowering inflammatory cytokine secretion. However, in periodontal patients, neutrophil recruitment to the gingival crevice is maintained despite the presence of gingipains.

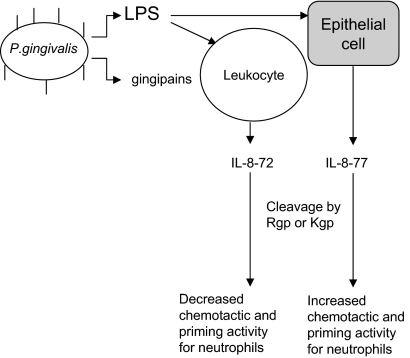

It is probable that an alternative mechanism exists to promote neutrophil chemotaxis and activity at periodontitis sites which may involve the secretion of the longer form of IL-877aa by nonimmune cells. This in vitro study provides a possible mechanism for P. gingivalis-manipulated neutrophil chemotaxis into periodontal pockets via activation of IL-877aa, as illustrated by Fig. 5. In conclusion, products from P. gingivalis may regulate host neutrophil accumulation at infected periodontal sites by initially stimulating the production of IL-877aa by nonimmune cells (e.g., epithelium) and promoting gingipain-dependent modification of IL-877aa into a more biologically active chemokine which promotes neutrophil chemotaxis and priming. Thereafter, after prolonged degradation by gingipains, the modified IL-877aa may reduce chemotaxis and neutrophil priming, thus prolonging the inflammatory lesion. Such a model (Fig. 5) is worthy of further investigation.

FIG. 5.

Schematic representation of gingipain-modulated IL-8 response. P. gingivalis stimulates production of host proinflammatory mediators, including IL-8. IL-877aa (IL-8-77) secreted by host epithelial cells can be cleaved into more active, truncated forms. Collectively with IL-872aa (IL-8-72), these truncated forms may recruit more neutrophils to the site of infections and also prime their activation, which may contribute to the increased hyperactivity of neutrophils in periodontitis. Prolonged exposure to gingipains may trigger further degradation of IL-877aa which may reduce chemotaxis and neutrophil priming, thus prolonging the inflammatory lesion.

Editor: J. L. Flynn

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano, A. 2003. Molecular interaction of Porphyromonas gingivalis with host cells: implication for the microbial pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 7490-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggiolini, M., A. Walz, and S. L. Kunkel. 1989. Neutrophil-activating peptide-1/interleukin 8, a novel cytokine that activates neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 841045-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calkins, C. C., K. Platt, J. Potempa, and J. Travis. 1998. Inactivation of tumour necrosis factor α by proteinases (gingipains) from the periodontal pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis: implications of immune evasion. J. Biol. Chem. 2736611-6614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapple, I. L. C. 1997. Periodontal disease diagnosis: current status and future developments. J. Dent. 253-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapple, I. L. C. 1997. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in inflammatory diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 24287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapple, I. L. C., and J. B. Matthews. 2007. The role of reactive oxygen and antioxidant species in periodontal tissue destruction. Periodontol. 2000 43160-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapple, I. L. C., G. R. Brock, C. Eftimiadi, and J. B. Matthews. 2002. Glutathione in gingival crevicular fluid and its relation to local antioxidant capacity in periodontal health and disease. J. Clin. Pathol. Mol. Pathol. 55367-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernando, H., G. T. Nagle, and K. Rajarathnam. 2007. Thermodynamic characterization of interleukin-8 monomer binding to CXCR1 receptor N-terminal domain. FEBS J. 274241-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figueredo, C. M., R. G. Fischer, and A. Gustafsson. 2005. Aberrant neutrophil reactions in periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 76951-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gimbrone, M. A., Jr., M. S. Obin, A. F. Brock, E. A. Luis, P. E. Hass, C. A. Herbert, Y. K. Yip, D. W. Leung, D. G. Lowe, W. J. Kohr, W. C. Darbonne, K. B. Bechtol, and J. B. Baker. 1989. Endothelial interleukin-8: a novel inhibitor of leukocyte-endothelial interactions. Science 2461601-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths, H. R. 2005. ROS as signalling molecules in T cells—evidence for abnormal redox signalling in the autoimmune disease, rheumatoid arthritis. Redox Rep. 10273-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guichard, C., E. Pedruzzi, C. Dewas, M. Fay, C. Pouzet, M. Bens, A. Vandewalle, E. Ogier-Denis, M. A. Gougerot-Pocidalo, and C. Elbim. 2005. Interleukin-8-induced priming of neutrophil oxidative burst requires sequential recruitment of NADPH oxidase components into lipid rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 28037021-37032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebert, C. A., F. W. Luscinskas, J. M. Kiely, E. A. Luis, W. C. Darbonne, G. L. Bennett, C. C. Liu, M. S. Obin, M. A. Gimbrone, Jr., and J. B. Baker. 1990. Endothelial and leukocyte forms of IL-8 conversion by thrombin and interactions with neutrophils. J. Immunol. 1453033-3040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubers, A. R., S. L. Kunkei, R. F. Todd, and S. J. Weiss. 1991. Regulation of transendothelial neutrophil migration by endogeneous interleukin-8. Science 25499-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imamura, T. 2003. The role of gingipains in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 74111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malkowski, M. G., B. J. Lazar, P. H. Johnson, and B. F. B. Edwards. 1997. The amino-terminal residues in the crystal structure of connective tissue activating peptide-III (des 10) block the ELR chemotactic sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 266367-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews, J. B., H. J. Wright, A. Roberts, N. Ling-Mountford, P. R. Cooper, and I. L. C. Chapple. 2007. Neutrophil hyper-responsiveness in periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 86718-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews, J. B., H. J. Wright, A. Roberts, P. R. Cooper, and I. L. C. Chapple. 2007. Hyperactivity and reactivity of peripheral blood neutrophils in chronic periodontitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 147255-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikolajczyk-Pawlinska, J., J. Travis, and J. Potempa. 1998. Modulation of interleukin-8 activity by gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis: implications for pathogenicity of periodontal disease. FEBS Lett. 440282-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milward, M. R., I. L. C. Chapple, H. J. Wright, J. B. Matthews, and P. R. Cooper. 2007. Differential activation of NF-κB and gene expression in oral epithelial cells by periodontal pathogens. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 148307-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyasaki, K. T. 1991. The neutrophil: mechanisms of controling periodontal bacteria. J. Periodontol. 62761-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa, H., S. Hainkeyama, A. Ikesu, and H. Miyai. 1991. Generation of interleukin-8 by plasmin from AVLPR-interleukin-8, the human fibroblast-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor. FEBS Lett. 282412-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nourshargh, S., J. A. Perkins, H. J. Showell, K. Matsushima, T. J. Williams, and P. D. Collins. 1992. A comparative study of the neutrophil stimulation activity in vitro and pro-inflammatory properties in vivo of 72 amino acid and 77 amino acid IL-8. J. Immunol. 148106-111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohashi, K., M. Naruto, T. Nakaki, and E. Sano. 2003. Identification of interleukin-8 converting enzyme as cathepsin L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 164930-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padrines, M., M. Wolf, A. Walz, and M. Baggiolini. 1994. Interleukin-8 processing by neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G and proteinase-3. FEBS Lett. 352231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sai, J., G. Walker, J. Wikswo, and A. Richmond. 2006. The IL sequence in the LLKIL motif in CXCR2 is required for full ligand-induced activation of Erk, Akt, and chemotaxis in HL60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 28135931-35941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Socransky, S. S., A. D. Haffajee, M. A. Cugini, C. Smith, and J. R. L. Kent. 1998. Microbial complexes in sub-gingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25134-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang, K. K., B. G. Dorner, U. Merkel, B. Ryffel, C. Schütt, D. Golenbock, M. W. Freeman, and R. S. Jack. 2002. Neutrophil influx in response to a peritoneal infection with Salmonella is delayed in lipopolysaccharide-binding protein or CD14-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 1694475-4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yun, P. L. W., A. A. Decarlo, and N. Hunter. 1999. Modulation of major histocompatibility complex protein expression by human gamma interferon mediated by cysteine proteinase-adhesin polyproteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 672986-2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]