Abstract

Alginate production in mucoid (MucA-defective) Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent upon several transcriptional regulators, including AlgB, a two-component response regulator belonging to the NtrC family. This role of AlgB was apparently independent of its sensor kinase, KinB, and even the N-terminal phosphorylation domain of AlgB was dispensable for alginate biosynthetic gene (i.e., algD operon) activation. However, it remained unclear whether AlgB stimulated algD transcription directly or indirectly. In this study, microarray analyses were used to examine a set of potential AlgB-dependent, KinB-independent genes in a PAO1 mucA background that overlapped with genes induced by d-cycloserine, which is known to activate algD expression. This set contained only the algD operon plus one other gene that was shown to be uninvolved in alginate production. This suggested that AlgB promotes alginate production by directly binding to the algD promoter (PalgD). Chromosome immunoprecipitation revealed that AlgB bound in vivo to PalgD but did not bind when AlgB had an R442E substitution that disrupted the DNA binding domain. AlgB also showed binding to PalgD fragments in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay at pH 4.5 but not at pH 8.0. A direct systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment approach showed AlgB binding to a 50-bp fragment located at bp −224 to −274 relative to the start of PalgD transcription. Thus, AlgB belongs to a subclass of NtrC family proteins that can activate promoters which utilize a sigma factor other than σ54, in this case to stimulate transcription from the σ22-dependent PalgD promoter.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative opportunistic pathogen that causes acute septicemia in patients with severe burns or immunodeficiency and chronic pneumonia in individuals with the genetic disease cystic fibrosis (CF) (2). Chronic lung infection by P. aeruginosa is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in CF patients (12). Upon pulmonary infection, P. aeruginosa readily converts to a mucoid phenotype that is characterized by overproduction of alginate, an exopolysaccharide that is comprised of a linear copolymer of β-d-mannuronic and α-l-guluronic acids (10). Alginate confers a selective advantage to P. aeruginosa in the CF lung by protecting the bacterium from the killing mechanisms of phagocytes and by preventing phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils (33, 41-43). Due to the strong selective advantage that alginate confers, research into the mechanism of alginate regulation and production could provide useful therapeutic targets for control of this chronic bacterial infection.

Alginate production is controlled by a complex regulatory hierarchy, which includes an alternative sigma factor and three regulatory proteins. The key element in the regulatory cascade is σ22 (also known as AlgT or AlgU), which is a member of the σE family of extracytoplasmic function sigma factors (9, 22). The activity of σ22 is modulated by the mucABCD gene products, which are encoded by the algT operon (15, 26). The majority of mucoid P. aeruginosa isolates derived from CF patients harbor mutations in mucA, and inactivation of mucA or mucB in wild-type nonmucoid P. aeruginosa strains causes induction of alginate synthesis (13, 23, 24). A membrane complex formed by MucA and MucB is involved in the posttranscriptional regulation of σ22 (26). MucA, an anti-sigma factor, has an affinity for σ22 and negatively regulates its activity (38, 51). σ22 autoregulates the algT promoter (9) and induces at least four other genes or operons that are required for alginate biosynthesis, including algR (25, 49), algB (14, 20, 47, 49), amrZ (50), and the algD operon encoding the majority of the alginate biosynthetic enzymes (5, 8, 49).

The algB and algR genes encode proteins that have homology to response regulators belonging to the two-component superfamily (31), and these proteins belong to the NtrC and LytR subfamilies, respectively (7, 28, 48). Interestingly, neither AlgB nor AlgR requires phosphorylation of the conserved aspartic acid residue in the regulator domain to promote alginate production in mucoid P. aeruginosa (20), thus eliminating any obvious role for their cognate sensor histidine kinases (KinB and FimS, respectively). Both AlgB and AlgR control alginate levels by activating transcription of the algD operon (5, 8, 49). AlgR activates algD expression by directly binding to three segments of the algD promoter, two of which are unusually far upstream of the transcription start site (19, 27). However, the mechanism by which AlgB stimulates algD transcription has remained unclear. Previous attempts to demonstrate direct interaction between AlgB and the promoter region of algD (PalgD) have been unsuccessful, suggesting that AlgB may control PalgD indirectly (46). However, in this investigation we used a variety of other DNA binding and transcriptome analyses to determine the role of AlgB in alginate biosynthesis, all of which showed that AlgB binds directly to the promoter of the algD operon for alginate biosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The P. aeruginosa strains used in this study, which are listed in Table 1, had the nonmucoid PAO1 (mucA+) or mucoid CF isolate FRD1 (mucA22) strain background, as indicated below. In addition, sequence-defined transposon insertion mutants, representing the PA1235, PA1261, PA1637, PA1979, PA2881, PA3329, PA3420, PA3771, and PA5431 genes, were obtained from the University of Washington saturation transposon insertion PAO1 library (18); the Tcr allele of each gene was transduced with phage F116L into the mucoid strain PDO351 (mucA::aacC1) background. All bacteria were cultured in L broth (Difco) or on L agar plates. The medium used for selection of P. aeruginosa and counterselection of Escherichia coli following triparental mating was a 1:1 mixture of L agar and Pseudomonas isolation agar (Difco). Sucrose plates (for sacB-mediated counterselection) contained sucrose at a concentration of 5% (wt/vol) in L agar. The selective antibiotics used have been described previously (20).

TABLE 1.

P. aeruginosa strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Characteristics or sequence | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) phoA supE44 λ−thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| MH10906 (RBB184) | F− λ−galK2 rpsL200 IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 himA ΔSmaI himDΔ3::cat | 47 |

| JM109 | endA1 recAl gyrA96 thi hsdR17 (rK− mK+) relA1 supE44 Δ(lac-proAB) (F′ traD36 proAB lacIqZΔM15) | Promega |

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type (nonmucoid) | This laboratory |

| PDO300 | PAO1 mucA22 (mucoid) | 26 |

| PDO351 | PAO1 mucA::aacC1 (mucoid) | 45 |

| PDO402 | PDO300 mucA22 algB::aacC1 | This study |

| PDO403 | PDO300 mucA22 kinB::aacC1 | This study |

| PDO405 | PAO1 kinB::aacC1 | This study |

| PDO406 | PDO300 mucA22 kinB::aacC1 | This study |

| WFPA5 | PAO1 ΔalgB::ΩaacC1 | This study |

| PDO411 | PAO1 algB48(R442E) | This study |

| PDO412 | PAO1 mucA::aacC1 algB48(R442E) | This study |

| FRD1 | Mucoid CF isolate, mucA22 | This laboratory |

| FRD444 | FRD1 algB::Tn501 | 20 |

| FRD840 | FRD1 mucA22 algBΔ::aacC1 | 20 |

| FRD842 | FRD840 mucA22 algB48 (encoding H-AlgB.R442E) | 20 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAL206 | pBluescript II with algB::aacC1 | This study |

| pUS51 | pEX100T with algB48 (encoding AlgB.R442E) | 20 |

| pUS64 | pEX100T with algBΔ::aacC1 | 20 |

| pUCGM | aacC1 (Gmr) cassette | 40 |

| pMOB3 | sacB oriT cassette | 39 |

| pAL209 | Vector with algB | This study |

| pAL271 | Vector with mucA::aacC1 | This study |

| pDJW408 | pTrcHisA with algB23 (H-AlgBΔ1-145) | 20 |

| pAS67a | pTrcHisC with algB49 (encoding H-AlgBΔ1-145.R442E) | This study |

| Primers | ||

| algBIP1+ | GCAGAGCAACTTGAAACCGTCTC | This study |

| algBIP1− | GCCGTTACTACGAGCCCCG | This study |

| algB53 | CGGAATTCATCGGCAGCGGC | 20 |

| algB54 | CGGGATCCTGGAATCGCACAGCC | 20 |

| ChIPneg+ | CATGCACTGGCTGGACTACC | This study |

| ChIPneg− | AGCGAGCGCCCGCCGTCATG | This study |

| algD5 | AAGGCGGAAATGCCATCTCC | This study |

| algD7 | AGGGAAGTTCCGGCCGTTTG | This study |

| algD8 | AATGGCCACTAGTTGCAGAA | This study |

| algD9 | CTTAATCTTCGACCCATGCA | This study |

| algD16 | GGTGAACGCGTAACTTTCAG | This study |

| algD17 | CGCAGAGAAAACATCCTATC | This study |

| algD18 | TCGATTGTTTGTCGCGCCGT | This study |

| algD29 | CGCGTTCACCGGAATGAAAC | This study |

| algD51 | ACCAGCCTCCCGCCATTA | This study |

| algD52 | CGCCATTACATGCAAAT | This study |

Genetic manipulations.

A mucA algB double mutant, PDO402, was generated from mucoid strain PDO300 and the algB knockout vector pAL206 using standard allelic exchange gene replacement techniques. Briefly, pAL206 was generated by subcloning an algB gene containing a 7,588-bp HindIII fragment from MTP331 (17) into pBluescript II SK (Stratagene). This plasmid was then cleaved with MluI and end filled with the Klenow fragment, and a SmaI-cut 900-bp ΩaacC1 cassette (encoding resistance to gentamicin [Gmr]) was cloned from pUCGM. The plasmid was then treated with NotI, and a cassette containing the sacB gene from pMOB3 was incorporated to provide counterselection. A mucA kinB double mutant, PDO403, was generated by F116L phage transduction-mediated gene replacement of kinB::ΩaacC1 (Gmr) from PDO405 in mucoid strain PDO300 using established techniques (30). To generate plasmid pAS67a, a 900-bp algB fragment was generated by PCR with oligonucleotides algB53 and algB54 using plasmid pUS5 as a template. This fragment was cloned into BamHI-EcoRI-digested pTrcHisC, resulting in pAS67a, which expressed a truncated His-tagged AlgB(R442E) protein. To generate strain WFPA5, a 5.1-kb EcoRI-ClaI fragment from plasmid pUS63 was cloned into pEX100T, resulting in pUS64 (Table 1). This plasmid was transferred to P. aeruginosa as described previously (20) to generate WFPA5. An algB(R442E) mutant, PDO411, was generated by allelic exchange using WFPA5 (ΔalgB::ΩaacC1) and pUS51 (20), and then a mucA::aacC1 mutation was introduced using pAL271 to construct the mucA algB(R442E) strain PDO412. All mutant strains were confirmed by PCR and/or Southern hybridization analysis.

DNA-protein cross-linking and ChIP.

A previously described chromosome immunoprecipitation (ChIP) protocol (32) was adapted as follows. Individual strains were grown in 100 ml of L broth until mid-exponential phase. The cultures were treated with 1.2% formaldehyde for 10 min at 37°C. Cross-linking was quenched by adding glycine to a final concentration of 330 mM, and then cells were sedimented by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, washed twice with ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl), and resuspended in 500 μl FA lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8], 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with lysozyme (5 mg per ml). Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor and sodium dodecyl sulfate (final concentration, 0.5%) were added. The resuspended pellet was sonicated (six 10-s pulses; duty, 90; output limit, 2,500; Sonic Dismembrator) and centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 rpm and 4°C. The supernatant was sonicated (six 10-s pulses), centrifuged as described above, and transferred to a new tube. A sample (500 μl) of this solution was used for immunoprecipitation, which was performed by addition of 500 μl FA lysis buffer with 10 μl goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G magnetic beads (3.65 × 1010 particles/ml) and 10 μl anti-AlgB (20), and then incubated overnight at 4°C on a rolling wheel. The magnetic beads were sedimented using an NEB magnetic separation rack and washed once with FA lysis buffer, once with FA lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, once with buffer III (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8], 250 mM LiCl, 1% Igepal, 1% sodium deoxycholate), and three times with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). The magnetic bead-bound complexes were eluted twice (total volume, 200 μl) with 100 μl of elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) for 10 min at 60°C. To each 200-μl sample 200 μl of Tris and 6 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml) were added, and this was followed by incubation at 65°C overnight. The DNA was extracted twice with phenol-chloroform and was ethanol precipitated with 2 μl of tRNA carrier. After centrifugation, the immunoprecipitated DNA was dissolved in 200 μl of water. The primer pairs that were used for PCR detection of specific DNA fragments are shown in Table 1.

AlgB protein purification.

AlgB and AlgB(R442E) were overexpressed from plasmids pDJW408 and pAS67a, respectively, in E. coli MH10906 (47). Strains were grown to mid-log phase (A580, 0.5 to 0.8). Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and cultures were incubated for an additional 3 h at 37°C with shaking. Pelleted cells were resuspended in fractionation buffer with glycerol (FBG) (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol). The suspension was stored at −70°C overnight, thawed, and lysed with a French press (twice at 14,000 lb/in2; Thermo Electron). Cells were centrifuged at 4°C twice at 14,000 × g for 11 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm acrodisc filter, and 5.0 ml was mixed with 2.0 ml of FBG-equilibrated Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin slurry (Qiagen) and placed on a rotary mixer for 1 h at 4°C. The mixture was applied to a polypropylene column (Qiagen), and liquid was allowed to drain by gravity flow. The column was washed four times with 10 ml of wash buffer (FBG with 1% Tween 20 and 10 mM imidazole). AlgB was eluted stepwise with 500 μl of 0.5, 1.0, or 2.0 M imidazole in FBG. Eluates were pooled and dialyzed against FBG to remove imidazole.

Immunoblot analysis.

Polyclonal antisera against recombinant His6-AlgB was generated in New Zealand White rabbits (Immunodynamics, Inc.) and used in a Western immunoblot analysis at a dilution of 1:50,000. Signal detection with chemiluminescent reagents was performed according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Pierce).

EMSA.

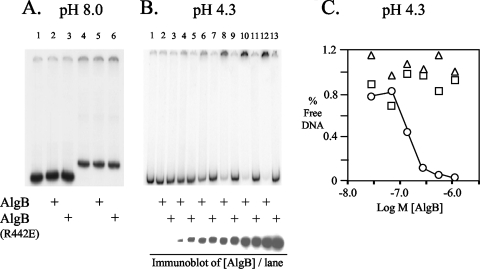

A 300-bp algD DNA fragment designated fragment A (obtained with algD5 and algD7 [Table 1; see Fig. 3]) was radiolabeled using [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci mmol−1; Amersham) and Taq polymerase (Promega) by PCR as previously described (49). This fragment was incubated with 69 nM His6-AlgB or His6-AlgB(R442E), 1.5 μg poly(dI-dC), and binding buffer (4 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 40 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 4% glycerol) for 15 min at room temperature. Samples were run on a 4% polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate-EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer at 200 V for 3 h at 4°C. Following drying for 50 min at 80°C (Bio-Rad gel dryer), the gel was analyzed with a Typhoon Phosphorimager. For a low-pH electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), PalgD fragment A (positions −324 to −24) and fragment B (positions −24 to 356) (see Fig. 3A) were radiolabeled using primers algD5 and algD7 and primers algD17 and algD18, respectively, as described above. Each fragment was incubated with His6-AlgB or His6-AlgB(R442E) at concentrations of 28, 70, 139, 278, 556, and 1,111 nM with 1.5 μg poly(dI-dC) and binding buffer. Electrophoresis was conducted using a 4% polyacrylamide gel in acetate-buffered saline (pH 4.3) (0.05 M sodium acetate, 0.025 M NaCl) at 100 V for 8 h at 4°C. Following drying for 50 min at 80°C (Bio-Rad gel dryer), the gel was analyzed with a Typhoon 8600 Phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics). Loss of algD DNA was measured using ImageQuant 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics).

FIG. 3.

EMSA of AlgB with PalgD. (A) EMSA performed at pH 8.0. Lanes 1 to 3 contained PalgD positions −324 to −24 relative to the transcriptional start site and AlgB or AlgB(R442E) as indicated. Lanes 4 to 6 contained PalgD positions −24 to 356 and AlgB or AlgB(R442E) as indicated. (B) EMSA performed at pH 4.3. All lanes contained PalgD positions −324 to −24 and either AlgB or AlgB(R442E) as indicated. Beneath the gel is a Western blot for AlgB and AlgB(R442E) used at concentrations of 28 nM (undetectable) to 1,111 nM. (C) The reduction in migration of PalgD DNA positions −324 to −24 (Fig. 3B) was quantitated and observed in lanes containing His-AlgB (○) but not in lanes containing His-AlgB(R442E) (□) or with AlgB and nonspecific PalgD DNA positions −24 to 356 (▵).

Direct SELEX enrichment.

A 1/25 dilution of the Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid magnetic agarose bead slurry (Qiagen) was saturated with 600 ng of purified recombinant His6-AlgB or His6-AlgB(R442E) for 1 h at room temperature on a rotary mixer. Protein-coated beads were collected magnetically, and the supernatant was discarded. The beads were then washed twice with 250 μl of systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX enrichment) buffer 1 (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM imidazole 5% glycerol, 1% Tween). A binding reaction mixture consisting of 1.2 ng of the DNA fragment to be tested, 45 ng of poly(dI-dC), and up to 30 μl of SELEX enrichment buffer 2 (4 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 40 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 20 mM imidazole, 4% glycerol) was added to the AlgB- or AlgB(R442E)-coated beads. Following incubation for 1 h at room temperature on a rotary mixer, protein-DNA complexes were isolated magnetically and washed as described above. AlgB-bound DNA fragments were eluted with 50 μl of SELEX enrichment buffer 2 at 75°C for 15 min. The resulting DNA pool was amplified by PCR (15 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min) and analyzed on a 0.7% agarose gel. The SELEX enrichment procedure was repeated as necessary using the PCR-amplified eluate from the previous round as the starting material. DNA fragments A and B used in this assay (see Fig. 3A) were generated as outlined above. DNA fragments C, D, E, F, G, and H (see Fig. 3A) were generated with oligonucleotides algD5 and algD8, algD5 and algD9, algD5 and algD29, algD16 and algD7, algD5 and algD51, and algD52 and algD9, respectively (Table 1).

RNA isolation and preparation for Affymetrix GeneChip analysis.

For RNA isolation, three independent replicates were obtained from the following P. aeruginosa strains grown overnight on L agar plates at 37°C: mucoid strain PDO300 (mucA22 allele), nonmucoid strain PDO402 (mucA22 algB), and mucoid strain PDO403 (mucA22 kinB). Approximately 1 × 109 cells were scraped from the plates and washed twice in cold phosphate-buffered saline. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy mini-kit with on-column DNase digestion (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (10 μg) was used for cDNA synthesis, fragmentation, and labeling according to the Affymetrix GeneChip P. aeruginosa genome array expression analysis protocol. Briefly, random hexamers (final concentration, 25 ng/μl; Invitrogen) were added to the total RNA (10 μg) along with in vitro-transcribed Bacillus subtilis control spikes as described in the Affymetrix GeneChip P. aeruginosa genome array expression analysis protocol. cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions under the following conditions: 25°C for 10 min, 37°C for 60 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 70°C for 10 min. RNA was removed by alkaline treatment and subsequent neutralization. The cDNA was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and was eluted in 40 μl of buffer EB (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5). The cDNA was fragmented with DNase I (0.6 U per μg of cDNA; Amersham) at 37°C for 10 min and then end labeled with biotin-ddUTP using an Enzo BioArray terminal labeling kit (Affymetrix) at 37°C for 60 min. Proper cDNA fragmentation and biotin labeling were determined by a gel mobility shift assay performed with NeutrAvadin (Pierce), followed by electrophoresis through a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gel and subsequent DNA staining with SYBR gold (Roche).

Microarray data analysis.

Microarray data were generated using protocols of Affymetrix. Absolute expression levels of transcripts were normalized for each chip by global scaling all probe sets to a target signal intensity of 500. Two statistical algorithms (detection and signal log ratio) were then used to identify differential gene expression in experimental and control samples. The detection metric (present, absent, or marginal) for a particular spot was determined using default parameters in the GCOS software (version 1.2; Affymetrix). Further analysis was performed by importing pivot data tables generated by GCOS into Genespring (version 7.2; Silicon Genetics). Only spots that were identified as present in at least three of the nine samples were used for further analysis. Signal log ratio values were converted from log2 values and expressed as fold changes. The statistical significance of differences between control and experimental conditions (P ≤ 0.2) for individual transcripts was determined using the t test. Finally, the false-discovery-rate algorithm of Benjamini and Hochberg was applied to all final data sets as a multiple-test correction to control for false positives (1). The original raw data files have been deposited in the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics, Inc.-Genomax shared workspace.

RESULTS

Transcriptional profile of the AlgB regulon in a mucoid derivative of P. aeruginosa PAO1 suggests that AlgB promotes alginate biosynthesis only at the algD promoter.

Previous data regarding AlgB clearly show that this response regulator is essential for alginate synthesis and PalgD expression (14, 48, 49). However, it was unclear if AlgB directly activates PalgD or if it operates indirectly by controlling the expression of another regulator required for PalgD expression. To address this issue, we performed a transcriptome analysis. An Affymetrix P. aeruginosa GeneChip microarray based on the genome of strain PAO1 was available (44), so we used mucoid (i.e., mucA-defective) strains with the PAO1 background for this part of the study. Strains PDO300 (mucA22), PDO402 (mucA22 algB), and PDO403 (mucA22 kinB) were grown on L agar at 37°C for 24 h, which stimulated alginate production. The algB mutant displayed a nonmucoid phenotype, and PDO402(pAL209) with algB+ in trans restored the mucoid phenotype to this mutant by complementation (data not shown). PDO403 was a kinB mutant of mucoid strain PDO300, which retained the mucoid phenotype on L agar, thus verifying that phosphorylation of AlgB by KinB is not required for alginate production under these conditions, as previously shown (20). The roles of AlgB and KinB in alginate gene regulation have been examined previously only in the CF isolate FRD1 (20, 21), so these observations confirmed that AlgB is an integral positive regulator of alginate production in different strains of P. aeruginosa, including PAO1.

The mechanism by which AlgB regulates PalgD was investigated by comparing the transcriptome expression in mucoid (mucA22) strain PDO300 to the transcriptome expression in the isogenic PDO402 (algB) and PDO403 (kinB) mutants. The genes examined were the genes that showed a >2-fold difference. The P value was kept relatively high (P > 0.2) in order to avoid excluding genes potentially under AlgB control, even though this would retain numerous false positives. Direct targets of AlgB potentially involved in PalgD expression would be expected among the set of 341 genes showing reduced expression in nonmucoid strain PDO402 (mucA22 algB) compared to mucoid strain PDO300 (mucA22). Comparison of the transcriptomes of PDO300 (mucA22) and PDO402 (mucA22 algB) clearly showed that the expression of the algD operon was higher in the AlgB+ strain, as expected (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

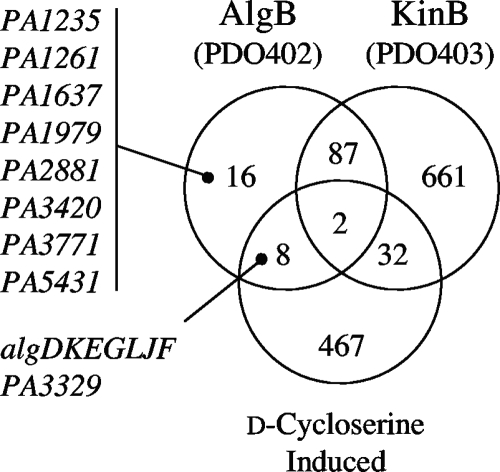

The transcriptome of mucoid strain PDO300 (mucA22) was also compared to that of mucoid strain PDO403 (mucA22 kinB) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Because control of PalgD by AlgB is apparently independent of phosphorylation by KinB (20), we examined just the 24 genes (Fig. 1) that appeared to be down-regulated in the algB mutant (PDO402) and unchanged in the kinB mutant (PDO403). Within this set were eight genes predicted to encode transcriptional regulators: PA1235, PA1261, PA1637, PA1979, PA2881, PA3420, PA3771, and PA5431 (Fig. 1). To test whether any of these potentially AlgB-regulated genes were involved in alginate regulation, a mutant analysis of each gene was performed. A sequence-defined transposon insertion mutant representing each regulator gene was obtained from the University of Washington saturation transposon insertion PAO1 library (18), and the Tcr allele was transduced into mucoid strain PDO351 (mucA::aacC1). Since all of the mutants constructed retained the mucoid phenotype on L agar (data not shown), the results suggested that AlgB does not regulate PalgD transcription through one of these genes as a downstream intermediate regulator.

FIG. 1.

Sets of genes up-regulated by AlgB in mucoid strain PAO1. The Venn diagram shows the overlap of genes that are >2-fold (P = 0.2) up-regulated by AlgB (PDO402 algB::aacC1) but not by KinB (PDO403 kinB::aacC1). This includes a set of eight hypothetical regulatory proteins shown here by mutant analysis to be not part of the alginate regulation pathway. Also shown in the Venn diagram is the inclusive (P = 0.2) set of genes that are >2-fold up-regulated by exposure of PAO1 to d-cycloserine (400 mg/ml for 60 min), which up-regulates the algD operon. This set contains only eight genes that overlap with the AlgB-dependent, KinB-independent set, only one of which was not in the alginate operon.

Evidence supporting the hypothesis that AlgB regulates PalgD directly was also obtained by another transcriptome comparison approach. We exploited the recent discovery that many antibiotics targeting peptidoglycan synthesis (e.g., d-cycloserine) cause activation of PalgD in PAO1 in an AlgB-dependent and σ22-dependent fashion (45). This provided a convenient way of inducing PalgD expression without a mucA mutation. When PAO1 was exposed to a sub-MIC level of d-cycloserine (400 μg/ml for 1 h in L broth), 509 genes appeared to be >2-fold up-regulated, again using a P value of >0.2 to avoid exclusion of any relevant genes. When this set of genes was compared to the set of genes under putative AlgB-only control, there were only eight genes in common (Fig. 1): algDKEGLJF of the algD operon encoding enzymes for alginate biosynthesis and PA3329, which encodes a hypothetical protein with homology to nonribosomal peptide synthases (according to the current annotation at www.pseudomonas.com). However, when a PA3329 mutant was constructed with mucoid strain PDO351 (mucA::aacC1), it retained the mucoid phenotype and thus showed that PA3329 was not involved in PalgD regulation in mucoid P. aeruginosa strains. Thus, these microarray comparisons suggested that AlgB may regulate PalgD by its direct interaction with PalgD of the operon for alginate biosynthesis.

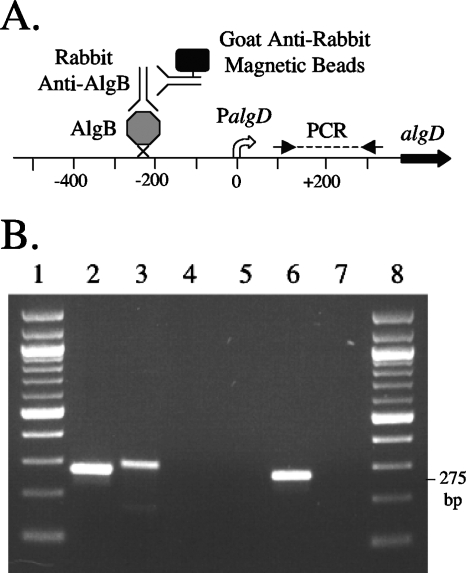

ChIP analysis shows a direct AlgB-PalgD interaction.

We previously showed that an algB allele (algB48) expressing AlgB(R442E) with a mutation in the proposed helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif does not complement a P. aeruginosa algB mutant and restore alginate production (20). This strongly suggests that AlgB binds to a specific promoter region to control alginate production. Although AlgB regulates PalgD, demonstrating a direct interaction in vitro has heretofore been difficult (46). Thus, an in vivo approach was employed, using a ChIP technique. DNA-protein cross-linking was performed by formaldehyde treatment of live cells of mucoid strain PDO351 (mucA::aacC1), followed by immunoprecipitation of AlgB from lysates using AlgB antibodies using a sandwich technique (Fig. 2A). The captured DNA fragments were then assayed by PCR using primers specific for the PalgD region. The results demonstrated the presence of PalgD sequences in the AlgB immunoprecipitates (Fig. 2B, lane 6). In contrast, no PalgD sequences were detected in the AlgB(R442E) immunoprecipitates (lane 7), indicating that the AlgB-PalgD interaction was specific. In addition, a negative control primer set was used to amplify the algE region several kilobases downstream in the operon (lane 3); in the ChIP assay, this produced no product with either AlgB (lane 4) or AlgB(R442E) (lane 5), confirming that the immunoprecipitates were not contaminated with nonspecific chromosomal DNA. Thus, these data provided convincing evidence that in vivo, AlgB directly binds to PalgD in mucoid P. aeruginosa strains.

FIG. 2.

ChIP of AlgB chromosomal immunoprecipitates. (A) Map of the algD region with the position of the PCR fragment used for ChIP analyses shown. AlgB bound to algD sequences in vivo was captured by cross-linking and immunoprecipitation using rabbit anti-AlgB and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G magnetic beads. (B) ChIP analyses. P. aeruginosa strains were treated with formaldehyde to cross-link AlgB to promoters and lysed, and AlgB complexes were immunoprecipitated for analysis. Lanes 1 and 8, NEB 100-bp DNA ladder; lane 2, PCR positive control (primers algBIP1+ and algBIP1− with chromosomal DNA) for amplification of a 275-bp fragment internal to the algD promoter; lane 3, PCR positive control (primers ChIPneg+ and ChIPneg− with chromosomal DNA) for amplification of a 289-bp product located elsewhere in chromosome; lane 4, PDO351 (AlgB+) failed to precipitate primers ChIPneg+ and ChIPneg− in a negative control for DNA contamination; lane 5, PDO412 [AlgB(R442E)] failed to precipitate primers ChIPneg+ and ChIPneg− in a negative control for DNA contamination; lane 6, PDO351 (AlgB+) precipitated primers algBIP1+ and algBIP1−; lane 7, PDO412 [AlgB(R442E)], defective in the HTH, failed to precipitate primers algBIP1+ and algBIP1−.

EMSA of AlgB with algD DNA shows binding at low pH.

To obtain evidence that AlgB binds directly to PalgD sequences in vitro, purified hexahistidine-tagged AlgB and AlgB(R442E) proteins were mixed with labeled 300-bp fragments A and B of PalgD located at positions −324 to −24 and −24 to 356, respectively, relative to the transcriptional start site. The reaction mixtures were incubated and evaluated using a standard EMSA (pH 8). Under these conditions, no change in the mobility of the DNA was observed with either AlgB protein compared to free DNA (Fig. 3A), as previously reported (46). However, this was inconsistent with the results of the ChIP assay described above, which showed AlgB binding to PalgD in vivo. It is known that pH can affect the mobility of some DNA-protein complexes (4, 37). Since AlgB has a theoretical pI of 5.1, based on the amino acid sequence, (48), we examined the possibility that AlgB-PalgD complexes could be visualized at a lower pH. Indeed, at pH 4.3 the migration of PalgD fragment A (positions −324 to −24) was retarded (i.e., the fragment remained in the wells) with increased concentrations of His6-AlgB, and a concomitant loss of free DNA was observed (Fig. 3B). No mobility shift was observed when fragment A was incubated with the same increased amounts of His6-AlgB(R442E) at pH 4.3 (Fig. 3B). An immunoblot of the His6-AlgB and His6-AlgB(R442E) proteins showed that equivalent amounts were used (Fig. 3B, bottom panel). The loss of PalgD due to increased His-AlgB was also plotted and compared to the results for His-AlgB(R442E) using both specific and nonspecific algD DNA (Fig. 3C). Overall, these EMSA studies indicated that the interaction of AlgB with PalgD fragment A (positions −324 to −24) was sequence specific.

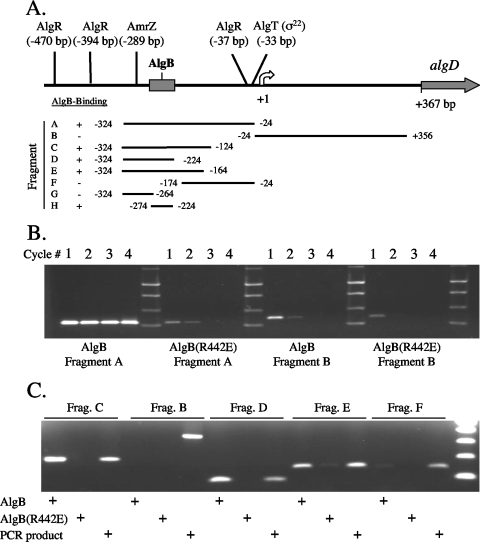

Mapping of the AlgB binding site on the algD promoter.

The algD promoter contains a large 367-bp leader region between the ATG start codon of algD and the start of transcription (position 1). There is another large upstream noncoding region (>300 bp) with known binding sites for the positive regulators AlgR and AmrZ (Fig. 4A). To locate the approximate AlgB binding site on PalgD, a direct SELEX enrichment approach, similar to one previously described (29), was used. Ni2+ magnetic beads coated with AlgB or AlgB(R442E) were incubated with PalgD promoter fragments A and B, washed, and then eluted with stringent SELEX enrichment buffer to remove any bound DNA fragments. Due to residual nonspecific DNA binding and the high sensitivity of PCR, nonspecific DNA fragments are often captured in the first round of SELEX enrichment. This was evident when PalgD fragment B (positions −24 to 356) was used with wild-type AlgB, as well as when the large PalgD fragment A (positions −324 to −24) and fragment B were used with AlgB(R442E) (Fig. 4B). However, after consecutive rounds of elution and PCR amplification, nonspecific binding, like that seen in the second and third rounds, was no longer visualized (Fig. 4B). When fragment A was used, specific PalgD DNA was recovered in each cycle with wild-type AlgB (Fig. 4B). Thus, the AlgB-DNA complex was specific for sequences upstream of the start of transcription, which was consistent with the DNA binding patterns shown in Fig. 2 and 3.

FIG. 4.

Mapping the AlgB binding site on PalgD using a direct SELEX enrichment assay. (A) Map of the PalgD region showing the binding sites for AlgT (σ22), AlgR, AmrZ, and AlgB. The endpoints of the DNA fragments used (fragments A to H) relative to the start of transcription (position 1, indicated by a curved arrow) are indicated. (B) Direct SELEX enrichment assay using the upstream region of PalgD (positions −224 to −24) (fragment A) or leader region of PalgD (positions −24 to 356) (fragment B). PalgD DNA in eluates from columns containing AlgB or AlgB(R442E) were PCR amplified and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Only PalgD fragment A (positions −224 to −24) was recovered in each cycle with AlgB but not with AlgB(R442E). (C) Direct SELEX enrichment assay to localize the AlgB binding site. Two-cycle SELEX enrichment assays were performed with PalgD fragments B, C, D, E, and F (panel A) and with AlgB or AlgB(R442E). The “PCR product” was included to illustrate the size of each fragment, using genomic DNA as a template. AlgB, but not AlgB(R442E), bound to algD fragments C, D, and E, all of which contained the region of PalgD from position −224 to position −324.

To map the location of AlgB binding, smaller PalgD fragments were used in a two-cycle direct SELEX enrichment analysis (Fig. 4C). AlgB bound to fragments C, D, and E, whereas AlgB(R442E) did not show specific binding. However, fragment F (positions −174 to −24) was not recovered after one round of SELEX enrichment with either the AlgB- or AlgB(R442E)-bound beads. Thus, all positive reaction mixtures with AlgB contained the 100-bp region between positions −324 and −224 (fragment D). When this 100-bp fragment was divided in half, fragment H (positions −274 to −224) appeared to show AlgB-specific binding, while fragment G (positions −324 to −274) failed to bind AlgB (data not shown). Thus, the AlgB binding site was located just downstream of the AmrZ binding site (Fig. 4A). Attempts to further resolve the AlgB binding site by EMSA or footprinting techniques are in progress.

DISCUSSION

It has been known for some time that AlgB is required for the mucoid (alginate-producing) phenotype (14) and for high expression of the alginate biosynthetic operon (48). However, the molecular mechanism of AlgB's action in P. aeruginosa has been elusive (46). AlgB shows homology to the well-characterized NtrC family of two-component DNA binding regulators, which suggests that there is a similar molecular mechanism for AlgB. NtrC-like proteins typically have a domain structure with an N-terminal phosphorylation-regulatory domain, an ATP binding domain, and a C-terminal HTH domain (20, 48). The unphosphorylated regulatory domain usually has a negative effect on its central ATP binding domain, which is overcome via phosphorylation by a cognate kinase to promote oligomerization and transcriptional activation of target promoters. However, it is interesting that phosphorylation of AlgB by its cognate kinase, KinB, is not required for the mucoid phenotype (20) or for stress induction of PalgD in wild-type P. aeruginosa (45). The mechanism by which AlgB's binding to PalgD contributes to transcriptional activation is unknown, but it may involve DNA bending to bring AlgR, bound far upstream, near σ22.

The present study began with analyzing the complete transcriptome responsive to AlgB. A microarray chip representing the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome was available, which allowed us to survey the regulon under AlgB control. Mutants with defects in algB or kinB were constructed with a mucoid (mucA22) strain PAO1 background; their nonmucoid and mucoid phenotypes were the same as those of the CF isolate FRD1, which provided reassuring evidence that AlgB plays an important role in alginate gene regulation in any strain. A broadly inclusive AlgB regulon (P > 0.2) potentially consisting of 113 genes was examined, which overlapped with 89 putatively KinB-coregulated genes. Thus, AlgB is apparently phosphorylated by KinB to control another regulon, which is currently being characterized. However, in this study, the KinB-coregulated genes were excluded because phosphorylation of AlgB by KinB is not required to promote alginate biosynthesis in a mucoid strain. The set of 24 AlgB-up-regulated (KinB-independent) genes contained eight putative transcriptional regulators based on homology, which might have included one regulator involved in alginate gene regulation if AlgB controlled its expression to indirectly control PalgD. However, mutations in each of the eight putative transcriptional regulators had no effect on alginate production in a mucoid (mucA) strain background, thus providing genetic evidence that the AlgB-PalgD interaction was direct.

Recent studies have shown that exposing wild-type (nonmucoid) P. aeruginosa to cell wall-damaging agents, such as d-cycloserine (400 μg/ml), causes strong activation of PalgD (45). This effect is dependent upon the regulators AlgB, AlgR, and σ22 but is independent of KinB, which mimics the effect seen in mucoid (mucA) P. aeruginosa (45). To further examine whether AlgB might control an unknown gene required for PalgD activation, we examined the overlap between the genes that are up-regulated by AlgB, in a KinB-independent fashion, and the genes that are up-regulated by cell wall stress. For the latter, we used all 467 genes that showed twofold induction by 1 h of exposure to d-cycloserine, again using a high P value (P < 0.2) to avoid excluding genes even though false positives would be retained. Interestingly, this widely inclusive comparison of genes up-regulated by AlgB (KinB independent) and by cell wall stress yielded only genes belonging to the algD operon and one other gene, PA3329, encoding a conserved hypothetical protein with no predicted function. A PA3329 mutant was constructed, but no effect on the mucoid phenotype was observed. Therefore, the transcriptome results caused us to reevaluate the possibility that AlgB directly activates PalgD by binding to sequences within the promoter.

To address this issue, the first procedure employed was a ChIP procedure that allowed us to cross-link AlgB to its various target promoters and then isolate the protein-DNA complexes by immunoprecipitation. The results demonstrated that wild-type AlgB directly interacts with PalgD in vivo, whereas AlgB with a defective HTH domain showed no binding to PalgD. At first these results were contradicted by the fact that an AlgB-PalgD interaction could not be demonstrated in a standard EMSA (46; this study). However, here we demonstrated that a positive AlgB-PalgD EMSA reaction occurred when the reaction was performed at a lower pH, which is reasonable considering the acidic pI of AlgB. However, as shown by the ChIP and SELEX enrichment data, a lower pH is not essential for the binding of AlgB to algD; it is merely needed for complex stability during electrophoresis. A third technique to show AlgB-DNA interactions was employed with the SELEX enrichment method, and this analysis provided convincing evidence for specific AlgB-PalgD interactions. By testing various fragments of the PalgD region, the SELEX enrichment method also allowed us to map a small region (∼50 bp) of AlgB binding to PalgD, located between positions −274 and −224 relative to the start of algD transcription. Thus, the biochemical and genetic data presented here strongly suggest that AlgB controls alginate production directly and exclusively by binding to PalgD. Future studies will address the direct effect of AlgB on PalgD transcription, in combination with other transcription factors (e.g., AlgR. AmrZ, and σ22), using in vitro transcription assays.

Ongoing studies are attempting to determine the exact sequence in the PalgD DNA to which AlgB binds. Thus far, it has not been possible to find a putative binding site common to AlgB-regulated genes that were discovered in the microarray analysis. Using a bioinformatics approach, we searched for a putative AlgB binding site by looking for sequence homology in the PalgD region of other Pseudomonas species that also produce alginate and have an AlgB orthologue. Alignments of the algD promoter region were constructed for strains P. aeruginosa PAO1, P. fluorescens Pf-5, P. putida KT2440, P. syringae pv. tomato strain DC3000, and P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A, both individually with PAO1 and as multiple alignments (data not shown). Interestingly, little homology was seen between PAO1 and the other strains in σ22 recognition sequences (8, 9, 11) or the defined binding sites for AlgR (27) and AmrZ (36). Likewise, no obvious homology was evident for the 50- to 100-bp region that AlgB was shown to bind. Thus, an AlgB binding site could not be reliably extrapolated using these methods. Biophysical techniques (e.g., footprint analysis) and the appropriate conditions are currently being used in an effort to define the precise binding site for AlgB within PalgD. In addition, the AlgB regulon (P > 0.2) potentially contains 113 genes, most of which (89 genes) overlap with KinB-coregulated genes. Thus, AlgB is apparently phosphorylated by KinB to control another regulon, which is currently being characterized. Secondary verification of these genes is in progress, which should ultimately yield important information about the role of the AlgB regulon and its binding consensus sequence.

Although this study provided multiple lines of physical and genetic evidence showing that AlgB regulates PalgD by direct binding, it brings up another conundrum related to the fact that AlgB belongs to the NtrC family. Transcriptional regulators belonging to the NtrC class usually recognize DNA binding motifs far upstream from the downstream promoter element and work with the alternative σ54 factor (35). AlgB does bind to PalgD between positions −274 and −224 relative to the start of algD transcription, and so it does act far upstream of the −35/−10 promoter region and may be involved in bending DNA of the large upstream promoter region of PalgD. However, instead of σ54, the PalgD promoter uses the alternative extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σ22, a distant relative of σ70, in mucA mucoid strains (9) and in nonmucoid wild-type strains induced by d-cycloserine (45). Others have demonstrated that a mutation in rpoN (encoding σ54) does not reduce PalgD expression or alginate production in a typical mucA mutant, mucoid background, suggesting that algD operon transcription is directed by σ22 in mucA mutant strains (3). Recently, other NtrC family members, includinge TyrR in E. coli (34), HupR in Rhodobacter capsulatus (6), and PhhR in P. putida (16), have been shown to stimulate transcription from their target promoters with RNA polymerase and σ70. Thus, AlgB appears to belong to a subclass of NtrC family proteins that can activate promoters which utilize a sigma factor other than σ54 to stimulate transcription from the PalgD promoter.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the VCU Nucleic Acids Core Facility for assistance with the microarray analysis. We thank Laura Silo-Suh (this laboratory) for constructing the algB and kinB mutants (PDO402 and PDO403, respectively). We thank Michael Jacobs for providing mutants of PAO1 with characterized transposon insertions from the University of Washington mutant bank.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-19146 (to D.E.O.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, by Public Health Service grant HL58334 (to D.J.W.) from the National Institute of Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, by a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (to D.E.O.), and in part by Veterans Administrations medical research funds (to D.E.O).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 November 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamini, Y., and Y. Hochberg. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 57289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodey, G. P., R. Bolivar, V. Fainstein, and L. Jadeja. 1983. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5279-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher, J. C., M. J. Schurr, and V. Deretic. 2000. Dual regulation of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and sigma factor antagonism. Mol. Microbiol. 36341-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey, J. 1988. Gel retardation at low pH resolves trp repressor-DNA complexes for quantitative study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85975-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chitnis, C. E., and D. E. Ohman. 1993. Genetic analysis of the alginate biosynthetic gene cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa shows evidence of an operonic structure. Mol. Microbiol. 8583-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies, K. M., V. Skamnaki, L. N. Johnson, and C. Venien-Bryan. 2006. Structural and functional studies of the response regulator HupR. J. Mol. Biol. 359276-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deretic, V., R. Dikshit, M. Konyecsni, A. M. Chakrabarty, and T. K. Misra. 1989. The algR gene, which regulates mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, belongs to a class of environmentally responsive genes. J. Bacteriol. 1711278-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deretic, V., J. F. Gill, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1987. Gene algD coding for GDP-mannose dehydrogenase is transcriptionally activated in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 169351-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVries, C. A., and D. E. Ohman. 1994. Mucoid to nonmucoid conversion in alginate-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa often results from spontaneous mutations in algT, encoding a putative alternative sigma factor, and shows evidence for autoregulation. J. Bacteriol. 1766677-6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans, L. R., and A. Linker. 1973. Production and characterization of the slime polysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 116915-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Firoved, A. M., J. C. Boucher, and V. Deretic. 2002. Global genomic analysis of AlgU (σE)-dependent promoters (sigmulon) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and implications for inflammatory processes in cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 1841057-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilligan, P. H. 1991. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 435-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg, J. B., W. L. Gorman, J. L. Flynn, and D. E. Ohman. 1993. A mutation in algN permits transactivation of alginate production by algT in Pseudomonas species. J. Bacteriol. 1751303-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg, J. B., and D. E. Ohman. 1987. Construction and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa algB mutants: role of algB in high-level production of alginate. J. Bacteriol. 1691593-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govan, J. R. W., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrera, M. C., and J. L. Ramos. 2007. Catabolism of phenylalanine by Pseudomonas putida: the NtrC-family PhhR regulator binds to two sites upstream from the phhA gene and stimulates transcription with sigma70. J. Mol. Biol. 3661374-1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, B., C. B. Whitchurch, L. Croft, S. A. Beatson, and J. S. Mattick. 2000. A minimal tiling path cosmid library for functional analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 genome. Microb. Comp. Genomics 5189-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs, M. A., A. Alwood, I. Thaipisuttikul, D. Spencer, E. Haugen, S. Ernst, O. Will, R. Kaul, C. Raymond, R. Levy, L. Chun-Rong, D. Guenthner, D. Bovee, M. V. Olson, and C. Manoil. 2003. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10014339-14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato, J., and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1991. Purification of the regulatory protein AlgR1 and its binding in the far upstream region of the algD promoter in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 881760-1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma, S., U. Selvaraj, D. E. Ohman, R. Quarless, D. J. Hassett, and D. J. Wozniak. 1998. Phosphorylation-independent activity of the response regulators AlgB and AlgR in promoting alginate biosynthesis in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 180956-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma, S., D. J. Wozniak, and D. E. Ohman. 1997. Identification of the histidine protein kinase KinB in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its phosphorylation of the alginate regulator AlgB. J. Biol. Chem. 27217952-17960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin, D. W., B. W. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Characterization of a locus determining the mucoid status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: AlgU shows sequence similarities with a Bacillus sigma factor. J. Bacteriol. 1751153-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, M. H. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1993. Differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa into the alginate-producing form: inactivation of mucB causes conversion to mucoidy. Mol. Microbiol. 9497-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, M. H. Mudd, J. R. W. Govan, B. W. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 908377-8381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, H. Yu, and V. Deretic. 1994. Analysis of promoters controlled by the putative sigma factor AlgU regulating conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationship to σE and stress response. J. Bacteriol. 1766688-6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathee, K., C. J. McPherson, and D. E. Ohman. 1997. Posttranslational control of the algT (algU)-encoded σ22 for expression of the alginate regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and localization of its antagonist proteins MucA and MucB (AlgN). J. Bacteriol. 1793711-3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohr, C. D., J. H. J. Leveau, D. P. Krieg, N. S. Hibler, and V. Deretic. 1992. AlgR-Binding sites within the algD promoter make up a set of inverted repeats separated by a large intervening segment of DNA. J. Bacteriol. 1746624-6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolskaya, A. N., and M. Y. Galperin. 2002. A novel type of conserved DNA-binding domain in the transcriptional regulators of the AlgR/AgrA/LytR family. Nucleic Acids Res. 302453-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochsner, U. A., and M. L. Vasil. 1996. Gene repression by the ferric uptake regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: cycle selection of iron-regulated genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 934409-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohman, D. E., M. A. West, J. L. Flynn, and J. B. Goldberg. 1985. Method for gene replacement in Pseudomonas aeruginosa used in construction of recA mutants: recA-independent instability of alginate production. J. Bacteriol. 1621068-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parkinson, J. S., and E. C. Kofoid. 1992. Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2671-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perron, K., R. Comte, and C. van Delden. 2005. DksA represses ribosomal gene transcription in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by interacting with RNA polymerase on ribosomal promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 561087-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pier, G. B., F. Coleman, M. Grout, M. Franklin, and D. E. Ohman. 2001. Role of alginate O acetylation in resistance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to opsonic phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 691895-1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pittard, J., H. Camakaris, and J. Yang. 2005. The TyrR regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 5516-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter, S. C., A. K. North, and S. Kustu. 1995. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by NtrC, p. 147-158. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 36.Ramsey, D. M., P. J. Baynham, and D. J. Wozniak. 2005. Binding of Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgZ to sites upstream of the algZ promoter leads to repression of transcription. J. Bacteriol. 1874430-4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roder, K., and M. Schweizer. 2001. Running-buffer composition influences DNA-protein and protein-protein complexes detected by electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (EMSA). Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 33209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schurr, M. J., H. Yu, J. M. Martinez-Salazar, J. C. Boucher, and V. Deretic. 1996. Control of AlgU, a member of the sigma E-like family of stress sigma factors, by the negative regulators MucA and MucB and Pseudomonas aeruginosa conversion to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 1784997-5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schweizer, H. P. 1992. Allelic exchange in Pseudomonas aeruginosa using novel ColE1-type vectors and a family of cassettes containing a portable oriT and the counter-selectable Bacillus subtilis sacB marker. Mol. Microbiol. 61195-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schweizer, H. P. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamicin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques 15831-833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simpson, J. A., S. E. Smith, and R. T. Dean. 1988. Alginate inhibition of the uptake of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by macrophages. J. Gen. Microbiol. 13429-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simpson, J. A., S. E. Smith, and R. T. Dean. 1993. Alginate may accumulate in cystic fibrosis lung because the enzymatic and free radical capacities of phagocytic cells are inadequate for its degradation. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 301021-1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simpson, J. A., S. E. Smith, and R. T. Dean. 1989. Scavenging by alginate of free radicals released by macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 6347-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. L. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K.-S. Wong, Z. Wu, I. T. Paulsenk, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, R. E. W. Hancock, S. Lory, and M. V. Olson. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 959959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wood, L. F., A. J. Leech, and D. E. Ohman. 2006. Cell wall-inhibitory antibiotics activate the alginate biosynthesis operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: roles of sigma (AlgT) and the AlgW and Prc proteases. Mol. Microbiol. 62412-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woolwine, S., and D. Wozniak. 1999. Identification of an Escherichia coli pepA homolog and its involvement in suppression of the algB phenotype in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181107-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wozniak, D. J., and D. E. Ohman. 1993. Involvement of the alginate algT gene and integration host factor in the regulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa algB gene. J. Bacteriol. 1754145-4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wozniak, D. J., and D. E. Ohman. 1991. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgB, a two-component response regulator of the NtrC family, is required for algD transcription. J. Bacteriol. 1731406-1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wozniak, D. J., and D. E. Ohman. 1994. Transcriptional analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes algR, algB, and algD reveals a hierarchy of alginate gene expression which is modulated by algT. J. Bacteriol. 1766007-6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wozniak, D. J., A. B. Sprinkle, and P. J. Baynham. 2003. Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa algZ expression by the alternative sigma factor AlgT. J. Bacteriol. 1857297-7300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie, Z. D., C. D. Hershberger, S. Shankar, R. W. Ye, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1996. Sigma factor-anti-sigma factor interaction in alginate synthesis: inhibition of AlgT by MucA. J. Bacteriol. 1784990-4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.