Abstract

The halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii encodes two related proteasome-activating nucleotidase proteins, PanA and PanB, with PanA levels predominant during all phases of growth. In this study, an isogenic panA mutant strain of H. volcanii was generated. The growth rate and cell yield of this mutant strain were lower than those of its parent and plasmid-complemented derivatives. In addition, a consistent and discernible 2.1-fold increase in the number of phosphorylated proteins was detected when the panA gene was disrupted, based on phosphospecific fluorescent staining of proteins separated by 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Subsequent enrichment of phosphoproteins by immobilized metal ion and metal oxide affinity chromatography (in parallel and sequentially) followed by tandem mass spectrometry was employed to identify key differences in the proteomes of these strains as well as to add to the restricted numbers of known phosphoproteins within the Archaea. In total, 625 proteins (approximately 15% of the deduced proteome) and 9 phosphosites were identified by these approaches, and 31% (195) of the proteins were identified by multiple phosphoanalytical methods. In agreement with the phosphostaining results, the number of identified proteins that were reproducibly exclusive or notably more abundant in one strain was nearly twofold greater for the panA mutant than for the parental strain. Enriched proteins exclusive to or more abundant in the panA mutant (versus the wild type) included cell division (FtsZ, Cdc48), dihydroxyacetone kinase-linked phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system (EI, DhaK), and oxidoreductase homologs. Differences in transcriptional regulation and signal transduction proteins were also observed, including those differences (e.g., OsmC and BolA) which suggest that proteasome deficiency caused an up-regulation of stress responses (e.g., OsmC versus BolA). Consistent with this, components of the Fe-S cluster assembly, protein-folding, DNA binding and repair, oxidative and osmotic stress, phosphorus assimilation, and polyphosphate synthesis systems were enriched and identified as unique to the panA mutant. The cumulative proteomic data not only furthered our understanding of the archaeal proteasome system but also facilitated the assembly of the first subproteome map of H. volcanii.

Phosphorylation is one of the most important and widespread posttranslational modifications of proteins. Its usefulness comes in the form of its strong perturbing forces, which modulate structure and function in a profoundly effective manner (27). Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of proteins can occur quite rapidly, making this mechanism ideal for controlling adaptive responses to environmental cues and changing intracellular conditions. These appealing characteristics have made phosphorylation the modification of choice for regulating a number of vital cellular processes, many of which overlap between the branches of life. It is estimated that in eukaryotes, as much as 30% of the proteome is phosphorylated, with serine constituting 90% of the modified residues and threonine and tyrosine representing the other 10% (12, 55). Many of these modified proteins represent immune cell signaling pathways, circadian regulatory systems, cell division control components, and metabolic networks within plant and/or mammalian systems (19, 42, 54). In bacteria, phosphorylation of “two-component” signal transduction and phosphotransferase system (PTS) elements broadens the occurrence of protein phosphorylation to include histidine and aspartic acid residues (17, 55). Although less common, serine, threonine, and tyrosine phosphorylation is also emerging as a regulatory device of bacteria (17).

To date, there are only a modest number of proteins with confirmed phosphorylation sites among archaea (11, 27). Several of these mirror eukaryotic and/or bacterial counterparts in terms of modification status and function. Based on traditional radiolabeling experiments, such proteins as Halobacterium salinarum CheA and CheY are phosphorylated at sites identical to those of their two-component signal transduction bacterial homologs (45). The archaeal translation initiation factor 2α of Pyrococcus horikoshii is phosphorylated at Ser48 by a kinase (PH0512) related to the human double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (51). In both Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota, the initiator protein Cdc6 (Orc) is autophosphorylated by a DNA-regulated mechanism at a conserved Ser residue (10, 16). Likewise, the β subunit of 20S proteasomes from Haloferax volcanii is phosphorylated at a Ser residue (21). A zinc-dependent aminopeptidase, with a leucine zipper motif that associates with a CCT-TRiC family chaperonin, has also been shown to be phosphorylated in Sulfolobus solfataricus (8).

The advent of modern high-throughput phosphoenrichment and analytical tools provides the opportunity now to identify archaeal phosphoproteins on a large scale, including those that lack similarity to members of the bacterial or eukaryotic clades or for which modifications have not been predicted previously. This study, in which a comparative proteomic analysis of wild-type H. volcanii cells and those lacking proteasomal function through deletion of a primary proteasome-activating nucleotidase (PanA) was performed, exemplifies such a scenario. The analysis included a combination of high-throughput phosphoenrichment methods, subenrichment strategies, and tandem mass spectrometry (MS-MS).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

Immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) and metal oxide affinity chromatography (MOAC) materials were supplied by Qiagen (Valencia, CA) and Perkin-Elmer (Waltham, MA), respectively. Trizol reagent and Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein stain were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Mevinolin was from Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) materials were supplied by Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Reversed-phase C18 spin columns and trypsin were purchased from The Nest Group, Inc. (Southborough, MA) and Promega (Madison, WI), respectively. Restriction enzymes and other DNA-modifying enzymes were from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). Hi-Lo DNA and Precision Plus protein molecular mass standards were from Minnesota Molecular, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN) and Bio-Rad, respectively. All other chemicals and reagents were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Strains, media, growth conditions, and plasmids.

Escherichia coli strains DH5α and GM2163 (New England Biolabs) were, respectively, used for routine cloning and purification of plasmid DNA for transformation of H. volcanii according to the methods of Cline et al. (7). E. coli strains were grown in Luria broth supplemented with 100 mg ampicillin, 50 mg kanamycin, and/or 30 mg of chloramphenicol per liter as needed. For genetic analysis, H. volcanii strains were grown at 42°C in YPC medium as described in reference 1. H. volcanii medium was supplemented with 4 to 5 mg mevinolin per ml and/or 0.1 mg novobiocin per liter as needed. H. volcanii DS70 (56) served as the parent strain for the generation of the panA mutant strain GG102. The chromosomal copy of GG102 panA has a 187-bp deletion and an insertion of a modified Haloarcula hispanica hmgA gene (hmgA*) encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, which renders H. volcanii cells resistant to mevinolin (56). The following approach was used to generate GG102. Vent DNA polymerase was used for PCR amplification of the panA gene from H. volcanii genomic DNA using primer 1 (5′-CATATGATGACCGATACTGTGGAC-3′ and primer 2 (5′-GAATTCAAAACGAAATCGAAG GAC-3′) (NdeI and EcoRI sites are boldfaced). H. volcanii genomic DNA was prepared for PCR from colonies of cells freshly grown on YPC plates. In brief, cells were transferred into 30 μl distilled H2O using a toothpick, boiled (10 min), chilled on ice (10 min), and centrifuged (for 10 min at 14,000 × g). The supernatant (10 μl) was used as the template for PCR. The 1.28-kb PCR fragment was cloned into pCR-BluntII-TOPO (Invitrogen) to generate plasmid pJAM636. The fidelity of this insert was confirmed by DNA sequencing at the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research. The 1.5-kb NotI fragment of plasmid pMDS99, which carries hmgA* (56), was inserted into the BbvCI-to-NruI sites of panA carried on pJAM636 by blunt-end ligation to generate plasmid pJAM906. This suicide plasmid (pJAM906, which carries hmgA* and panA in the same orientation, as determined by restriction mapping using KpnI and AgeI) was transformed into H. volcanii DS70, and recombinants were selected on YPC solid medium supplemented with mevinolin. Isolated colonies were restreaked for isolation on fresh YPC solid medium plus mevinolin and were screened by PCR using primers that annealed outside the panA region of suicide plasmid pJAM906 (primer 3 [5′-TACGATAAGGACTCGGCGTCGCAGC-3′] and primer 4 [5′-TACGTC GCGTTCGCGGCGTAGTCAC-3′]). Clones that generated the appropriate PCR product were further screened by Western blotting using anti-PanA, anti-PanB, anti-α1, and anti-α2 antibodies as described previously (44). For complementation studies, H. volcanii-E. coli shuttle plasmids carrying panA and panB genes were transformed into mutant strain GG102. These plasmids, pJAM650 and pJAM1012, encode C-terminal polyhistidine-tagged PanA and PanB (PanA-His6 and PanB-His6), respectively, under the control of the Halobacterium cutirubrum rRNA P2 promoter and were constructed as follows. The 1.2-kb NdeI-HindIII fragment of pJAM642 and the 1.24-kb NdeI-XhoI fragment of pJAM1006 (44) were separately blunt-end ligated into the NdeI-BlpI site of pJAM202 (24) to replace psmB-his6 with panA-his6 (pJAM650) and panB-his6 (pJAM1012), respectively.

For growth rate and proteomic analyses, log-phase H. volcanii cells were grown in 25 ml (125-ml foil-capped Erlenmeyer flasks, 200 rpm, 42°C) of ATCC 974 medium and minimal medium (1), respectively. For proteomic analysis, cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0 to 1.2, harvested by centrifugation (at 10,000 to 14,000 × g and 4°C), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Protein extraction and quantification.

For IMAC analysis, protein was extracted from cells according to a previous study (25). For all other procedures, protein was extracted using Trizol according to protocols described previously (28). Samples were dried through vacuum centrifugation and stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations were determined by a Bradford protein assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard according to the supplier's instructions (Bio-Rad).

2-DE.

2-DE was carried out as described previously with 11 cm immobilized pH gradient strips and Criterion 12.5% resolving Tris-HCl gels (Bio-Rad) (28). Prior to separation, protein samples were reconstituted in an isoelectric focusing-compatible buffer consisting of 250 mM glycerol, 10 mM triethanolamine, and 5% (wt/vol) 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS). Proteins separated by 2-DE were stained in the gel with Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein stain according to the supplier's instructions (Invitrogen). Gels were imaged with the Molecular Imager FX scanner with a 532-nm excitation laser and a 555-nm LP emissions filter (Bio-Rad). Acquired images were analyzed with PDQuest (version 7.0.1) software (Bio-Rad).

Protein reduction, alkylation, and tryptic digestion.

Dried protein samples (300 μg) were resuspended in 100 μl of 50 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 7.5). Samples were reduced by the addition of 5 μl of 200 mM dithiothreitol (DTT solution) (for 1 h at room temperature or 21°C). Samples were alkylated by the addition of 4 μl of 1 M iodoacetamide (for 1 h at 21°C). Alkylation was stopped by the addition of 20 μl of DTT solution (for 1 h at 21°C). Samples were digested with a 1:20 ratio of trypsin to protein for 18 to 24 h at 37°C. Digested peptides were purified using 300-μl C18 spin columns and dried under vacuum centrifugation. In-gel proteins were reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin by using an automated platform for protein digestion (ProGest; Genomics Solutions, Ann Arbor, MI).

Peptide methyl esterification.

A 2 M concentration of methanolic acid was generated by adding 60 μl of acetyl chloride dropwise to 300 μl of anhydrous methanol in a glass tube. The mixture was sealed and incubated (for 10 to 15 min at 21°C). Dried tryptic peptides were mixed with 30 μl of the methanolic acid reagent and incubated in a sealed jar containing desiccative material for 90 min at 21°C. Methyl esterified samples were dried under vacuum centrifugation and reconstituted in mobile phase B (0.1% [vol/vol] acetic acid, 0.01% [vol/vol] trifluoroacetic acid, and 95% [vol/vol] acetonitrile) for MS-MS analysis.

IMAC.

Phosphoprotein enrichment by IMAC was performed using a phosphopurification system according to the supplier's instructions (Qiagen) with the following modifications. Extracted protein (2.5 mg) was resuspended in 25 ml of the supplied lysis buffer to a final concentration of 0.1 mg of protein per ml. Six 500-μl fractions per sample, as opposed to the suggested four, were collected for analysis.

Titanium dioxide phosphopeptide enrichment.

MOAC of H. volcanii DS70 and GG102 peptides was performed using the Phos-Trap phosphopeptide enrichment kit (catalog no. PRT301001KT; Perkin-Elmer) with the following modifications. Samples were agitated in the presence of 40 μl of elution buffer as opposed to the recommended 20 μl. Samples were incubated with the TiO2 resin for 10 min instead of 5 min and were incubated with elution buffer for 15 min instead of 10 min. The resulting samples were dried under vacuum centrifugation at 42°C for 30 min and reconstituted in mobile phase B for MS-MS analysis.

RP-HPLC coupled with nanoelectrospray ionization-QTOF (QStar) MS-MS.

Separation of peptides (desalted with a PepMap C18 cartridge) by capillary reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) was performed using a PepMap C18 column (15 cm [length] by 75 μm [inner diameter]) and an Ultimate Capillary HPLC system (LC Packings, San Francisco, CA). A linear gradient of 5% to 40% (vol/vol) acetonitrile for 25 min at 200 nl·min−1 was used for separation. MS-MS analysis was performed online using a hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) instrument (QStar XL hybrid LC/MS-MS) equipped with a nanoelectrospray source (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and operated with Analyst QS (version 1.1) data acquisition software. Information-dependent acquisition was employed in which each cycle consisted of a full scan from m/z 400 to 1,500 (1 s) followed by MS-MS (3 s) of the two ions that exhibited the highest signal intensity. In the full-scan acquisition mode, ions were focused through the first quadrupole by focusing and declustering potentials of 275 V and 55 V, respectively, and were guided to the TOF region via two quadrupole filters operated in radio frequency (rf)-only mode. Ions were orthogonally extracted, accelerated through the flight tube (plate, grid, and offset voltages were 340, 380, and −15 V, respectively), and refocused to a 4-anode microchannel plate detector via an ion mirror held at 990 V. The same parameters were utilized with the MS-MS mode of operation; however, the second quadrupole was employed to filter a specific ion of interest while the third quadrupole operated as a collision cell. Nitrogen was used as the collision gas, and collision energy values were optimized automatically using the rolling collision energy function based on m/z and the charge state of the peptide ion.

LCQ ion trap MS.

IMAC samples separated in the gel were analyzed with a Thermo LCQ Deca quadrupole ion trap MS (LCQ Deca MS) in line with a 5-cm (length) by 75-μm (inner diameter) Pepmap C18 5-μm-particle-size (300-Å mean pore diameter) capillary column (LC Packings). The HPLC device operating upstream of the MS system was run with a 60-min gradient from 5% to 50% mobile phase B with a flow rate of 12 μl·min−1. MS parent ion scans were followed by four data-dependent MS-MS scans.

MS data and protein identity analyses.

Spectra from all experiments were converted to DTA files and merged to facilitate database searching using the Mascot search algorithm (version 2.1; Matrix Science, Boston, MA) against the deduced H. volcanii proteome (assembly, 26 May 2006; http://archaea.ucsc.edu/). Search parameters included trypsin as the cleavage enzyme. Carbamidomethylation was defined as the only fixed modification in the search, while methionine oxidation, pyro-Glu from glutamine or glutamic acid, acetylation, and phosphorylation of serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues were set as variable modifications. Mass tolerances for all LCQ analyses were 2 Da for MS and 1 Da for MS-MS. Mass tolerances for all QStar analyses were 0.3 Da for both MS and MS-MS. Protein identifications for which a probability-based molecular weight search (MOWSE) score average of 30 or above was not assigned were excluded. Proteins were considered unique to GG102 panA or DS70 only if protein identities were exclusive for at least 2 samples per strain. Transmembrane spanning helices were predicted using TMHMM, version 2.0 (32). Phosphosites were predicted using NetPhos, version 2.0 (5). Proteins were categorized into clusters of orthologous groups (COG) using COGNITOR (53).

All phosphopeptides predicted by MS via the Mascot database search algorithm were filtered to include only those peptides that were top-ranking hits and had E values less than 3.0. The resulting list of phosphopeptide spectra was reviewed manually with Analyst QS (version 1.1) acquisition software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), with Scaffold software (version 1.6; Proteome Software, Portland, OR), and with spectral data generated through the Mascot search algorithm. The peptide fragment masses detected were compared with those in a theoretical peptide fragmentation spectrum generated by Protein Prospector, version 4.0.8 (P. R. Baker and K. R. Clauser; http://prospector.ucsf.edu). Mass additions of 80 Da (HPO3) or neutral losses of 98 Da (H3PO4) were confirmed mathematically through analysis of peptide fragmentation and correlation of detected diagnostic ions present in the corresponding spectrum. Consideration was also given to spectral quality, including peak intensity and completeness of generated ion series, in the screening of spectral data for confirmation of modification. Theoretical lists of modified internal ions were also generated, searched, and assigned in the actual spectra.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of the H. volcanii panA mutant GG102.

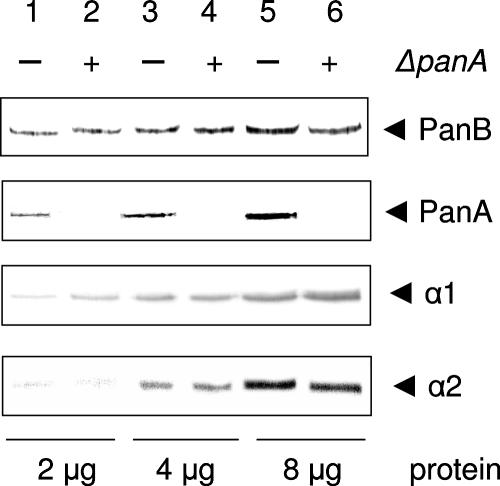

In addition to three 20S proteasomal proteins (α1, α2, and β), H. volcanii encodes two proteasome-activating nucleotidase proteins (PanA and PanB), which are 60% identical. Of these, the α1, β, and PanA proteins are relatively abundant during all phases of growth (on rich medium at moderate temperatures, 37 to 42°C) (44). In contrast, the levels of PanB and α2 are relatively low in the early phases of growth and increase severalfold during the transition to stationary phase (44). To further investigate the function of the predominant Pan protein, PanA, a mutation was generated in the chromosomal copy of the panA gene. A suicide plasmid, pJAM906, was used to generate this mutation, in which panA had a 187-bp deletion in addition to an insertion of the H. hispanica mevinolin resistance marker. Recombinants were selected on rich medium supplemented with mevinolin and screened by colony PCR using primers which annealed outside the chromosomal region that had been cloned onto the suicide plasmid. Approximately 10% of the clones that were screened generated the expected panA mutant PCR product of 2.50 kb compared to the parent strain PCR product of 1.28 kb (data not shown). Of the PCR-positive clones, one (GG102) was selected for further analysis by Western blotting using anti-PanA antibodies. The PanA protein was readily detected by Western blotting for the parent strain, DS70 (Fig. 1). In contrast, PanA was not detected under any growth conditions for the panA mutant GG102, thus confirming the mutation.

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of the H. volcanii panA mutant strain GG102. Cell lysates of the parent strain, DS70, and the panA mutant, GG102, were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-PanA, -PanB, -α1, and -α2 polyclonal antibodies as indicated (where α1 and α2 are the α-type subunits of 20S proteasomes). Total protein (2, 4, and 8 μg) from DS70 (lanes 1, 3, and 5) and GG102 (lanes 2, 4, and 6) was separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis prior to analysis.

20S proteasome and PanB protein levels are not altered by the panA mutation.

To determine whether the panA mutation influenced the levels of 20S proteasome and/or Pan proteins, DS70 and GG102 were analyzed by Western blotting using polyclonal antibodies raised separately against the α1, α2, and PanB proteins (where α1 and α2 are subunits of 20S proteasomes). No differences in the levels of any of these three proteasomal proteins were detected between these two strains when they were grown to log phase in minimal medium (Fig. 1). Thus, H. volcanii does not appear to have a feedback mechanism to increase the levels of PanB or 20S proteasomes after a loss of PanA under the growth conditions examined in this study.

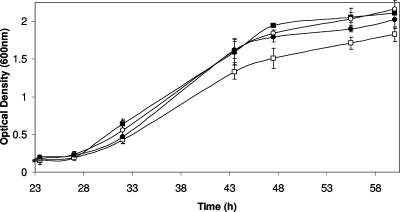

Growth phenotype of the panA mutant GG102 compared to its parental and complemented strains.

Comparison of GG102 panA to its parent, DS70, revealed significant differences in growth in rich medium (Fig. 2). This included an increase in the doubling time from 4.1 to 5.2 h as well as a decrease in the overall cell yield from an OD600 of 2.1 to 1.8. Both the doubling time and the overall cell yield were at least partially restored by complementation with plasmid pJAM650 or pJAM1020, encoding PanA-His6 or PanB-His6 protein, respectively. The ability of the pHV2-derived plasmid pJAM1020 to partially complement the panA mutation for growth may be due, at least in part, to the high-level expression of PanB from this plasmid, which includes both a strong rRNA P2 promoter of H. cutirubrum and a T7 terminator to mediate transcription of the panB-his6 gene fusion. This is likely to alter the levels of PanB protein, normally low in early phases of growth and increased severalfold during the transition to stationary phase. Although the PanA and PanB proteins may have overlapping functions based on this partial complementation for growth, these proteins differ significantly in primary sequence (by 40%) and growth phase-dependent regulation (44) and thus are likely to degrade proteins differentially in terms of substrate preference and/or rate.

FIG. 2.

Reduced growth phenotype of H. volcanii GG102 panA compared to its parent and complemented strains. The DS70 parent strain (▪), GG102 panA (□), GG102 panA(pJAM650) (○), and GG102 panA(pJAM1012) (•) were inoculated (1%) from log-phase cultures into 25 ml ATCC 974 medium at 42°C (200 rpm) in 125-ml Erlenmeyer flasks and were monitored for growth (OD600). Plasmids pJAM650 and pJAM1012 encode PanA-His6 and PanB-His6, respectively. Experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

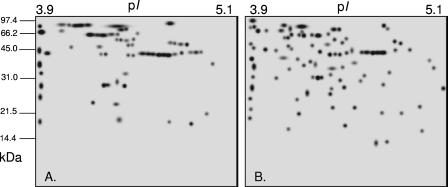

Comparative 2-DE analysis of the panA mutant and its parent.

Expression of the panA- and panB-his6 gene fusions using an rRNA P2 promoter on a high-copy-number plasmid is likely to alter the proteome composition of the complemented panA mutant from that of the “wild type.” To avoid this complexity, the parental strain, DS70, was used as the “wild type” for proteome comparison to the panA mutant GG102. Analysis of cell lysates of DS70 and GG102 by 2-DE revealed comparable numbers of total protein spots as detected by the Sypro Ruby protein stain: 333 (±17) and 314 (±14) spots, respectively. However, further analysis of the 2-DE-separated proteins by Pro-Q Diamond, a phosphoprotein-specific fluorescent dye developed by Steinberg et al. (50), revealed more than twice as many “phosphoprotein” spots for the panA mutant (64 ± 7) as for the wild type (31 ± 6) (Fig. 3). As many as 40 to 44% of the Pro-Q Diamond-stained phosphoproteins were not detected by Sypro Ruby and thus are likely to be present at relatively low levels in the cell. Interestingly, the limited impact of the panA mutation on the total number of protein spots detected by Sypro Ruby contrasts with the >1.7-fold increase after addition of the 20S proteasome-specific inhibitor clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone (cLβL) (29). This may reflect the central role of the N-terminal Thr proteolytic active site of the 20S β subunit, which is irreversibly inactivated by cLβL, in all proteasome-mediated protein degradation in this archaeon. In contrast, PanA and other closely related AAA+ ATPases are more likely to play upstream roles, including differential substrate recognition, unfolding, and translocation into the 20S proteasome core for degradation.

FIG. 3.

Total proteins of the H. volcanii parent strain, DS70 (A), and GG102, its panA mutant (B), separated by 2-DE and stained with the phosphospecific fluorescent protein stain Pro-Q Diamond. Protein molecular mass standards (Bio-Rad Low Range) and the range of the immobilized pH gradient strip used for isoelectric focusing are indicated on the left and at the top, respectively.

Phosphoprotein and phosphopeptide enrichments.

IMAC and MOAC were used in four separate experiments (experiments A to D) to enrich the cell lysates of the panA mutant (GG102) and its parent (DS70) for phosphoproteins and/or phosphopeptides. A similar 2-DE pattern of proteins was detected by Pro-Q Diamond staining before and after IMAC enrichment (data not shown). As an initial approach to protein identification, IMAC-purified samples were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1-dimensionally), and bands that appeared uniquely or in discernibly different amounts in the mutant were excised and digested in the gel with trypsin prior to hybrid MS-MS analysis (LCQ Deca MS) (experiment A). This analysis produced a modest number of protein identifications (a total of 10) with MOWSE scores of 30 or above and thus was not further pursued as a viable approach for high-throughput analysis of these strains. To overcome these limitations, biological triplicate samples of GG102 and DS70 were subjected to three separate approaches: (i) IMAC enrichment of proteins followed by cleavage with trypsin, (ii) MOAC enrichment of methyl esterified tryptic peptides, and (iii) IMAC enrichment of proteins followed by MOAC enrichment of methyl esterified tryptic peptides (experiments B to D, respectively). Peptides from all three of the latter approaches were separated by C18 RP-HPLC and analyzed online using electrospray ionization-QTOF hybrid MS.

In total, these approaches resulted in the identification of 625 proteins with MOWSE scores of 30 or above and with at least 2 peptides identified per protein (see Table S1A in the supplemental material; detailed proteomic data are available upon request). This corresponds to 15.4% of the deduced proteome of H. volcanii, based on the DS2 genome sequence minus proteins encoded by pHV2 (the plasmid cured from DS70 and its derivatives). The proteins identified ranged from 4.9 to 186 kDa, with an average molecular mass of 41.6 kDa. The majority of the proteins identified (523 proteins, or 83% of the total) were encoded on the 2.848-Mb chromosome. The coding sequences for the remaining 202 proteins were distributed among pHv4 (52 proteins), pHv3 (43 proteins), and pHv1 (7 proteins). This represents 8 to 17% of the coding capacity for each element (18% of the 2.848-Mb chromosome, 8.2% of pHv4, 11.2% of pHv3, and 7.9% of pHv1). Of the total proteins identified, 145 were based on high-probability scores and multiple peptide identifications within a single biological replicate and thus were not assigned as unique or common to DS70 or GG102. The remaining proteins were categorized as either common to GG102 and DS70 (328 proteins), unique to DS70 (57 proteins), or unique to GG102 (98 proteins) (see Table S1A in the supplemental material). The number of proteins identified by MS-MS in these phosphoprotein-enriched fractions that were exclusive to GG102 was nearly twofold higher than the number of identified proteins exclusive to DS70. This relative difference in MS-MS-identified strain-specific proteins is consistent with the differences observed in the number of Pro-Q Diamond-stained 2-DE gel spots from the proteomes of these two strains.

The 480 proteins that were categorized as either common to both strains or exclusive to one strain (DS70 or GG102 panA) were identified based on an average detection per protein of 4.7 tryptic peptides in 5 biological replicates and an average MOWSE score of 76. Among the proteins common to both strains, 8 to 9% were estimated to be more abundant in either GG102 (15 proteins) or DS70 (13 proteins) based on spectral counts. Of the total 625 proteins identified, only a small portion (32 proteins, or 5.1%) were predicted to form transmembrane spanning helices (TMH), compared to the approximately 22% putative TMH proteins encoded on the genome (see Table S1A in the supplemental material). The TMH proteins were detected primarily in GG102 (more than 80%), with nearly 50% classified as unique to this strain. A lower proportion of TMH proteins was detected in DS70 (53%) with only 2 of these (6%) grouped as exclusive to this strain. While the significantly higher number of identified predicted membrane proteins in the panA deletion strain than in the wild type is intriguing, the overall number identified is low, and they are likely to require preparation of membranes to enhance their detection (30).

Summaries of proteins identified as either unique to or more abundant in either GG102 or DS70 are given in Tables 1 and 2. At this stage in our understanding, it is not clear whether these differences in proteomes between the two strains reflect a change in the phosphorylation status of the protein or in overall protein abundance. However, the identification of these differences was reproducible. As a confirmation of the approaches, the PanA protein was exclusively and reproducibly detected in the DS70 parent strain across all proteomic analyses. The PanA protein was not detected in GG102, consistent with the targeted knockout of the encoding panA gene from the chromosome of this strain (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Proteins identified as unique to either the panA mutant GG102 or the parent strain, DS70a

| GenBank ORF no. | Predicted function or description |

|---|---|

| GG102panA mutant | |

| HVO_0035 | TMH protease regulator (stomatin, prohibitin) |

| HVO_0058 | Oligopeptide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

| HVO_0070 | NifU/thioredoxin-related protein (nifU) |

| HVO_0136 | Translation initiation factor eIF-1A |

| HVO_0177 | Arsenate reductase (ArsC) and protein tyrosine phosphatase (Wzb) related |

| HVO_0393 | Excinuclease ABC ATPase subunit (uvrA) |

| HVO_0433 | NADPH-dependent F420 reductase (npdG); dinucleotide binding |

| HVO_0446* | Phosphate/phosphonate ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein (phnC) |

| HVO_0448* | Imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase glutamine amidotransferase subunit (hisH) |

| HVO_0480 | 3-Phosphoglycerate kinase (pgk) |

| HVO_0519 | Replication A-related (single-stranded DNA-binding) protein (RPA) |

| HVO_0602 | 3-Dehydroquinate dehydratase (aroD) |

| HVO_0620 | Type II/IV secretion system and related ATPase |

| HVO_0627 | Dipeptide ABC transporter, ATP binding |

| HVO_0681 | TopA DNA topoisomerase I |

| HVO_0766 | Hsp20 molecular chaperone (ibpA) |

| HVO_0788 | Tryptophan synthase β subunit (trpB) |

| HVO_0829 | Prolyl oligopeptidase |

| HVO_0884 | Aldehyde reductase (COG0656) |

| HVO_0887* | 2-Oxoacid:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, β subunit |

| HVO_0889* | FAD/NAD binding oxidoreductase |

| HVO_0894 | Acetate-CoA ligase (acsA) |

| HVO_1009 | Oxidoreductase related to aryl-alcohol dehydrogenases (aad) |

| HVO_1022 | NADH:flavin oxidoreductase related to “Old Yellow Enzyme” (yqjM) |

| HVO_1027 | Twin arginine translocation TMH protein TatAo |

| HVO_1037 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_1047 | NADPH:quinone oxidoreductases (qor) |

| HVO_1061 | Thioredoxin reductase (trxB1) |

| HVO_1113 | FtsZ cell division GTPase |

| HVO_1121 | Heme biosynthesis protein (pqqE) |

| HVO_1170 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_1203 | Flagellar protein E-related |

| HVO_1272* | Transcriptional regulator |

| HVO_1273* | Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase, CBS pair domain |

| HVO_1289 | OsmC-like regulator (osmC) |

| HVO_1299 | HTH DNA-binding XRE-/MBF1-like protein |

| HVO_1309 | Xaa-Pro dipeptidase |

| HVO_1327 | Cdc48-related AAA+ ATPase |

| HVO_1446 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (fbp) |

| HVO_1495 | PTS IIB component (fruA) |

| HVO_1507 | Acetolactate synthase small regulatory subunit (ilvN) |

| HVO_1513 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_1527 | Glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (galU) |

| HVO_1576 | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (gmd) (COG0451) |

| HVO_1578 | NADH dehydrogenase, FAD-binding subunit |

| HVO_1588 | Cupin (small barrel) domain protein |

| HVO_1637 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase (slyD) |

| HVO_1649 | S-Adenosylmethionine synthetase |

| HVO_1650 | Polyphosphate kinase (ppk) |

| HVO_1654 | Cysteine synthase (cysK) |

| HVO_1788 | Ferredoxin-nitrite/sulfite reductase (nirA, cysI) |

| HVO_1830 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase |

| HVO_1894 | Conserved TMH protein |

| HVO_1932* | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (serA) |

| HVO_1936* | F420-dependent oxidoreductase |

| HVO_1973 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_2040 | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (gmd) (COG0451) |

| HVO_2045 | Hypothetical protein |

| HVO_2072 | Conserved TMH protein |

| HVO_2081 | Conserved TMH protein |

| HVO_2214 | MCP domain signal transducer TMH protein (Htr, Tar) (COG0840) |

| HVO_2270* | HsdM type I restriction enzyme |

| HVO_2271* | HsdS restriction endonuclease S subunit |

| HVO_2361 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large subunit (carB) |

| HVO_2374 | PhoU-like phosphate regulatory protein |

| HVO_2516 | 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase |

| HVO_2524 | Phytoene/squalene synthetase (crtB) |

| HVO_2542 | Ribosomal protein L15 (rplO) |

| HVO_2589 | Asparaginase |

| HVO_2622 | Aldehyde reductase (COG0656) |

| HVO_2661* | Aspartate aminotransferase (aspC) (COG0075) |

| HVO_2662* | Dioxygenase |

| HVO_2671 | Aminotransferase class V (COG0075) |

| HVO_2690 | MviM oxidoreductase |

| HVO_2716 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (acd) |

| HVO_2742 | Methionine synthase II (metE) |

| HVO_2759* | TET aminopeptidase |

| HVO_2760* | Nonconserved TMH protein |

| HVO_2767 | DNA/RNA helicase |

| HVO_2819 | Phage integrase family domain protein |

| HVO_2883 | snRNP-like protein |

| HVO_2948 | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase α chain (pheS) |

| HVO_2997 | O-Acetylhomoserine sulfhydrylase (OAH SHLase) |

| HVO_A0267 | Mandelate racemase/muconate lactonizing enzyme (COG4948) |

| HVO_A0331 | Mandelate racemase/muconate lactonizing enzyme (COG4948) |

| HVO_A0339 | ABC transporter extracellular solute-binding protein |

| HVO_A0472* | Thioredoxin reductase (trxB2) |

| HVO_A0476* | Conserved pst operon protein |

| HVO_A0477* | PstS phosphate ABC transporter, solute-binding protein |

| HVO_A0480* | PstB phosphate ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| HVO_B0130 | DNA-binding protein (DUF296) |

| HVO_B0173 | SMC-ATPase-like chromosome segregation protein |

| HVO_B0248 | Oxidoreductase (COG4221) |

| HVO_B0265 | Oxidoreductase |

| HVO_B0268 | Alkanal monooxygenase-like |

| HVO_B0291* | Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase (ugpQ) |

| HVO_B0292* | ABC-type transporter, glycerol-3-phosphate-binding protein (ugpB) |

| HVO_B0371 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase (putA) |

| DS70 parent strain | |

| HVO_0017 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_0043 | Aminotransferase (gabT, argD) |

| HVO_0117 | Translation initiation factor eIF-6 |

| HVO_0161 | ATP phosphoribosyltransferase (hisG) |

| HVO_0314 | Archaeal/vacuolar-type H+-ATPase subunit C/AC39 |

| HVO_0353 | Ribosomal protein S23 (S12, RpsL) |

| HVO_0420 | MCP domain signal transducer (Tar) (COG0840) |

| HVO_0549 | 2-Keto-3-deoxygluconate kinase |

| HVO_0730 | Transcription regulator transcribed divergently from inorganic pyrophosphatase in haloarchaea |

| HVO_0827 | Conserved protein (COG4746) |

| HVO_0850* | Proteasome-activating nucleotidase A (panA) |

| HVO_0853* | DNA double-strand break repair protein (mre11) |

| HVO_1085* | Bifunctional purine biosynthesis protein (purH) |

| HVO_1087* | Usp universal stress protein (COG0589) |

| HVO_1173 | SpoU-like RNA methylase (COG1303) |

| HVO_1228 | PetE plastocyanin/Fbr cytochrome-related protein |

| HVO_1245 | DsbA-/DsbG-like protein-disulfide isomerase (thioredoxin domain) |

| HVO_1426 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_1443 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| HVO_1472 | Putative transcriptional regulator with CopG DNA-binding domain |

| HVO_1492 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_1502 | 3-Isopropylmalate dehydrogenase (leuB) |

| HVO_1683 | 4-α-Glucanotransferase (malQ) |

| HVO_1741 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_1829 | Leucyl aminopeptidase T (pepB, ampS) |

| HVO_1901 | Translation initiation factor eIF-2γ (GTPase) |

| HVO_2102 | PTS enzyme II A component, putative |

| HVO_2126 | ABC transporter, oligopeptide-binding protein |

| HVO_2239 | Usp universal stress protein (COG0589) |

| HVO_2333 | Conserved protein |

| HVO_2504 | 3-Oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein reductase (atsC) (COG4221) |

| HVO_2514 | Transcriptional regulator (conditioned medium-induced protein 2, or Cmi2) |

| HVO_2614 | Uridine phosphorylase (udp) |

| HVO_2675 | Histidinol dehydrogenase (hisD) |

| HVO_2723* | snRNP homolog (LSM1) |

| HVO_2726* | Glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (gltX, glnS) |

| HVO_2738 | Ribosomal protein S28e (S33) |

| HVO_2782 | Ribosomal protein S11 (rpsK) |

| HVO_2798 | ABC transporter, branched-chain amino acid-binding protein |

| HVO_2899 | BolA-like morphogen |

| HVO_2916 | Short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase (fabG) |

| HVO_2943 | Dihydroorotate oxidase (pyrD) |

| HVO_2981 | Uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (upp) |

| HVO_A0078 | Helicase SNF2/RAD54 family |

| HVO_A0279 | Tnp transposase |

| HVO_A0295 | N-Carbamoyl-l-amino acid amidohydrolase (amaB) |

| HVO_A0386 | Hydantoin utilization protein B (hyuB) |

| HVO_A0388 | Transcriptional regulator, AsnC/Lrp family |

| HVO_A0487 | Cobyrinic acid a,c-diamide synthase (cobB) |

| HVO_A0635 | Aminotransferase class V (CsdB-related) |

| HVO_B0053 | Conserved protein in cobalamin operon |

| HVO_B0084 | GlcG-like protein possibly involved in glycolate and propanediol utilization |

| HVO_B0112 | Mandelate racemase/muconate lactonizing N-terminal domain protein (COG4948) |

| HVO_B0151 | Ribbon-helix-helix transcriptional regulator of CopG family |

| HVO_B0154 | OYE2 11-domain light- and oxygen-sensing His kinase, member of “two-component” system |

| HVO_B0233 | α-l-Arabinofuranosidase (xsa, abfA) |

| HVO_C0017 | Chromosome-partitioning ATPase (ParA, Soj) |

ORFs are numbered according to the H. volcanii genome available at http://archaea.ucsc.edu/ (A. Hartman et al., unpublished data). ORF numbers with asterisks are predicted to be cotranscribed or divergently transcribed. Underlining indicates paralogous ORFs identified as unique to either GG102 or DS70. COG numbers are included for these paralogues. Proteins were classified as “unique” if they were exclusively identified in at least two samples of either GG102 or DS70 with MOWSE score averages of 30 or higher and at least two peptide hits. Boldface indicates proteins with MOWSE score averages above 50.

TABLE 2.

Proteins identified as common but with higher spectral counts, suggesting greater abundance, for either the panA mutant GG102 or DS70

| GenBank ORF no.a | Predicted function and/or description | Exptb | MOWSE scorec

|

Spectral countsd

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS70 | GG102 | DS70 | GG102 | % Difference | |||

| HVO_1073 | DJ-1, PfpI family protein | B | 46 | 126 | 0 | 8 | 100 |

| HVO_1546 | Dihydroxyacetone kinase subunit DhaK | B | 49 | 78 | 0 | 7 | 100 |

| HVO_1496 | PstI phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase | B | 40 | 112 | 0 | 7 | 100 |

| HVO_2923 | 20S proteasome α2 subunit PsmC | B | 37 | 70 | 0 | 6 | 100 |

| HVO_0025 | Thiosulfate sulfurtransferase TssA | B, D | 41 | 100 | 0 | 6 | 100 |

| HVO_0581 | FtsZ cell division protein | B, D | 32 | 58 | 0 | 6 | 100 |

| HVO_0024 | Thiosulfate sulfurtransferase TssB | B | 35 | 95 | 0 | 5 | 100 |

| HVO_0350 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit A" | B | 41 | 89 | 0 | 4 | 100 |

| HVO_0348 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit B′ | B | 64 | 92 | 2 | 7 | 71 |

| HVO_0861 | SufB/SufD domain protein | B, D | 77 | 176 | 8 | 24 | 67 |

| HVO_0806 | Pyruvate kinase | B | 92 | 147 | 6 | 15 | 60 |

| HVO_2941 | Nonhistone chromosomal protein | B, D | 61 | 90 | 2 | 5 | 60 |

| HVO_0859 | Fe-S assembly ATPase SufC | A, B | 208 | 289 | 13 | 19 | 32 |

| HVO_2700 | Cdc48-like AAA+ ATPase | B | 171 | 252 | 14 | 19 | 26 |

| HVO_0359 | Translation elongation factor EF-1α | B, D | 392 | 546 | 34 | 45 | 24 |

| HVO_2748 | RNA polymerase Rpb4 | B | 117 | 34 | 9 | 0 | 100 |

| HVO_0055 | Conserved protein | B | 133 | 57 | 8 | 1 | 88 |

| HVO_0313 | ATP synthase (E/31 kDa) subunit | B | 92 | 56 | 5 | 1 | 80 |

| HVO_2543 | rpmD ribosomal protein L30P | B | 111 | 67 | 9 | 2 | 78 |

| HVO_2561 | rplB ribosomal protein L2 | B | 97 | 59 | 9 | 2 | 78 |

| HVO_1000 | Acetyl-CoA synthetase | B | 100 | 58 | 8 | 2 | 75 |

| HVO_1148 | Rps15p ribosomal protein S15 | B | 109 | 60 | 10 | 3 | 70 |

| HVO_1412 | dmd diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase | B | 104 | 61 | 3 | 1 | 67 |

| HVO_2384 | CBS domain pair protein | B | 96 | 64 | 5 | 2 | 60 |

| HVO_0214 | l-Lactate dehydrogenase | B | 166 | 105 | 16 | 7 | 56 |

| HVO_0536 | Nutrient stress-induced DNA-binding protein | B | 303 | 148 | 25 | 11 | 56 |

| HVO_0044 | argB acetylglutamate kinase | B | 117 | 77 | 8 | 4 | 50 |

| HVO_0324 | argS arginyl-tRNA synthetase | B | 78 | 46 | 4 | 2 | 50 |

ORFs are numbered according to the H. volcanii genome available at http://archaea.ucsc.edu/ (A. Hartman et al., unpublished data).

Experiments A, B, C, and D correspond to in-gel IMAC, total IMAC, MOAC, and IMAC-MOAC. respectively.

Average probability-based peptide matching scores from all experiments in which the protein was identified.

Average total spectral counts for all experiments in which the protein was identified.

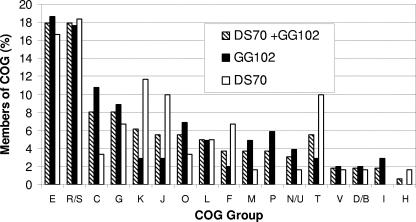

Categorization of “unique” proteins into COG.

The 156 proteins identified as exclusive to either GG102 or DS70 (listed in Table 1) were categorized into COG as indicated in Fig. 4 (for details, see Table S1B and C in the supplemental material). Overall, the largest percentage (36%) of these proteins was equally distributed between two groups: (ii) those of unknown or general function (R/S) and (ii) those involved in amino acid transport and metabolism (E). The remaining proteins clustered into a diversity of functional COG groups ranging from translation to signal transduction as outlined in Fig. 4. Comparison of the panA mutant to its parent (GG102 versus DS70) revealed notable differences in the distribution of “unique” proteins within many of these groups. In particular, the percentages of proteins exclusive to GG102 panA were considerably higher than those unique to DS70 in energy production and conversion (C), posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones (O), cell envelope biogenesis and outer membrane (M), and inorganic ion transport and metabolism (P). In contrast, the percentages of proteins that clustered to transcription (K), translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (J), and nucleotide transport and metabolism (F) were higher in DS70 than in GG102. The increased number of proteins involved in translation, nucleotide biosynthesis, and transcription for DS70 may be a reflection of the higher growth rate and overall cell yield of this strain compared to those of GG102 panA. Although the increased number of GG102-unique proteins clustering to energy production and conversion (C) would seem to contradict this suggestion, the vast majority of the latter proteins were oxidoreductases (10 out of 11), including a homolog of “Old Yellow Enzyme,” amounts of which have been shown to increase during periods of oxidative stress in Bacillus subtilis (14). The remaining GG102-unique protein of this cluster was a glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase (ugpQ), an enzyme that can be an indicator of phosphate starvation (2). In contrast to GG102, the two DS70-unique proteins that clustered to this general COG group (C) were predicted to be involved in the generation of proton motive force, including an ATP synthase subunit and plastocyanin-/cytochrome-like protein.

FIG. 4.

Proteins identified by MS-MS as exclusive to either the panA mutant (GG102) or parent (DS70) grouped according to the COG database. “Members of COG” represents the number of exclusive proteins which group to a particular COG as a percentage of total exclusive proteins identified by MS-MS for GG102 (solid bars), DS70 (open bars), and the sum of GG102 and DS70 (striped bars). COG groups listed include E (amino acid transport and metabolism), R/S (general function prediction only/function unknown), C (energy production and conversion), G (carbohydrate transport and metabolism), K (transcription), J (translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis), O (posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones), L (DNA replication, recombination, and repair), F (nucleotide transport and metabolism), M (cell envelope biogenesis, outer membrane), P (inorganic ion transport and metabolism), N/U (cell motility and secretion/intracellular trafficking), T (signal transduction mechanisms), V (defense mechanisms), D/B (cell division and chromosome partitioning), I (lipid metabolism), and H (coenzyme metabolism).

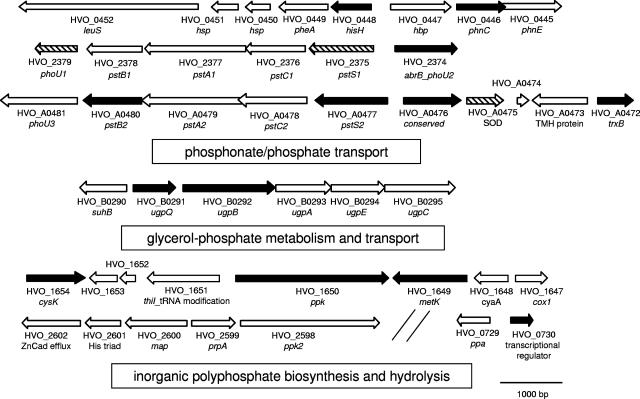

One of the most notable differences between the protein profiles of the panA mutant and its parent was linked to phosphorus assimilation and synthesis of polyphosphate (the PHO regulon, many members of which cluster to group P) (summarized in Fig. 5). Proteins of the PHO regulon identified exclusively in GG102 included homologs of phosphate/phosphonate ABC-type transporters (pstB2, pstS2, and phnC), PHO regulators (abrB_phoU2), polyphosphate kinase (ppk), ABC transporter glycerol-3-phosphate binding protein (ugpB), and glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase (ugpQ) (discussed above). Many additional proteins unique to GG102 were encoded within these genomic regions (i.e., hisH, HVO_A0476, trxB, metK, and cysK). In addition, a transcriptional regulator (HVO_0730) unique to DS70 was found to be divergently transcribed from a gene encoding inorganic pyrophosphatase (ppa). Components of the ABC-type Pst2 transporter uniquely identified in GG102 are encoded on pHV4 and appear ancillary to a paralogous ABC-type Pst1 transporter common to both DS70 and GG102, which is encoded on the 2.848-Mb chromosome. The up-regulation of components of phosphate uptake and metabolism typically corresponds to cellular stress (13, 52), with the levels of polyphosphate impacting cell survival (6). Proteomic and microarray analyses of archaeal species such as Methanosarcina acetivorans have revealed the PHO regulon to be expressed at higher levels during growth on the lower-energy-yielding substrate acetate than on methanol (38).

FIG. 5.

Organization of H. volcanii genes encoding proteins linked with phosphorus transport and metabolism that are altered by the panA mutation. Genes encoding relevant paralogs are also included. ORFs are numbered according to the genome assembly available at http://archaea.ucsc.edu/. ORFs encoding proteins unique to GG102 (solid arrows), unique to DS70 (shaded arrows), common to DS70 and GG102 (hatched arrows), and not detected in this study (open arrows) are indicated. Proteins include leucyl-tRNA synthetase (leuS); heat shock proteins (hsp); prephenate dehydratase (pheA); the glutamine amidotransferase subunit of imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase (hisH); phosphate binding protein (hbp); phosphonate/phosphate ABC transporter ATPase (phnC) and permease (phnE); regulatory proteins of phosphate assimilation and metabolism (phoU1 and phoU3); an protein homolog ambiactive regulator of transcription during transition between log and stationary phase fused to PhoU (abrB_phoU2); phosphate ABC transporter ATP-binding (pstB1 and pstB2), permease (pstA1, pstA2, pstC1, and pstC2), and solute-binding (pstS1 and pstS2) components; a conserved protein (HVO_0476, which is linked to all haloarchaeal pst operons identified to date); superoxide dismutase (SOD)transmembrane helix (TMH); thioredoxin reductase (trxB); inositol monophosphatase/NADPH phosphatase (suhB); glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase (ugpQ); glycerol-3-phosphate ABC transporter solute binding (ugpB), permease (ugpA and ugpE), and ATP-binding (ugpC) components; cysteine synthase (cysK); thiamine biosynthesis protein (thiI); polyphosphate kinases (ppk1 and ppk2); S-adenosylmethionine synthase (metK); adenylate cyclase (cyaA); cytochrome oxidase (cox1); zinc/cadmium cation efflux system (ZnCad efflux); histidine triad DNA-binding protein (His triad); methionine aminopeptidase type II (map); serine/threonine protein phosphatase (prpA); and inorganic pyrophosphatase (ppa). Proteins encoded by genes abbreviated as abrB_phoU2 and thiI_tRNA modification may be multifunctional. Bar, 1,000 bp of genomic DNA.

In addition to alterations in the PHO regulon, the panA knockout resulted in increased enrichment and identification of proteins linked to protein folding, Fe-S cluster assembly, and the oxidative stress response compared to those for the parent strain, DS70. These included components of a thiosulfate sulfurtransferase (tssA, tssB) and Fe-S assembly system (nifU, sufB, sufC), thioredoxin/disulfide reductases (trxB1 and trxB2), topoisomerase A (topA), replication A-related single-stranded DNA binding protein (RPA), excinuclease ABC ATPase subunit (uvrA), Old Yellow Enzyme (yqjM; discussed above), Hsp20 molecular chaperone (ibpA), OsmC-like regulator (osmC), peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase (slyD), S-adenosylmethionine synthase, and cysteine biosynthetic enzymes (e.g., dehydrogenase, O-acetylhomoserine sulfhydrylase) (Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, in E. coli the osmotically inducible OsmC is proposed to use highly reactive cysteine thiol groups to elicit hydroperoxide reduction (35) and is downstream of a complex phosphorelay system that includes regulation by the AAA+ proteases Lon and HslUV (33, 41).

A number of additional differences in transcription and signal transduction proteins were also observed between DS70 and GG102 panA. For example, subunits of RNA polymerase were altered by the panA mutation, with Rpb4 more abundant in DS70 fractions and RpoA and RpoB (α and β) more abundant in those of GG102 (Table 2). The altered levels of Rpb4 in DS70 versus GG102 are consistent with the recent finding that the levels of this protein are directly correlated with eukaryotic cell growth (i.e., cells expressing lower levels of Rpb4 grow more slowly than cells expressing higher levels) (48). In addition to the differences noted above, a BolA-like protein and conditioned medium-induced protein 2 (Cmi2) were identified exclusively in DS70. BolA triggers the formation of osmotically stable round cells when overexpressed in stationary-phase E. coli (46), and Cmi2, a putative metal-regulated transcriptional repressor, may be regulated by quorum sensing in H. volcanii (G. Bitan-Banin and M. Mevarech, GenBank accession no. AAL35835). A number of putative DNA-binding proteins and homologs of methyl-accepting chemotaxis (MCP) proteins were also found to be altered. In addition, a number of mandelate racemase/muconate lactonizing enzymes related to the E. coli starvation-sensing protein RspA (20) were altered by the panA mutation.

Some archaea do not encode Pan proteins (e.g., species of Thermoplasma, Pyrobaculum, and Cenarchaeum). Thus, it is speculated that Cdc48/VCP/p97 AAA+ ATPases, which are universal to archaea, may function with 20S proteasomes as in eukaryotes (22). Interestingly, two Cdc48-like AAA+ ATPases were identified as either exclusive or more abundant in GG102 panA than in DS70 (HVO_1327 and HVO_2700 [Tables 1 and 2, respectively]), suggesting that these proteins may compensate in part for the loss of the AAA ATPase function of PanA. A TMH homolog of prohibitin (HVO_0035) known to regulate AAA protease function (3) was also identified as exclusive to GG102.

Intriguing similarities also emerged between the proteomic profiles of this study and our previous work in which cells were treated with the 20S proteasome-specific inhibitor cLβL and analyzed by 2-DE (29). Specifically, three proteins that accumulated more than fivefold in cells treated with cLβL were also discovered in notably higher abundance in the panA mutant strain than in the parent strain of this study. This subset of proteins included the DJ-1/ThiJ family protease, the translation elongation factor EF-1α, and the Fe-S cluster assembly ATPase SufC (Table 2). In addition, FtsZ cell division protein homologs and components of the putative phosphoenolpyruvate PTS which appear to be coupled to dihydroxyacetone kinase (PtsI, DhaK, DhaL) were also found at higher levels in GG102 panA and cLβL-treated cells than in the wild type.

Phosphopeptide identification.

Based on favorable likelihood scores using the Mascot search algorithm and careful manual analysis of the peptide spectra, nine individual phosphosites, including four serine, four threonine, and one tyrosine modification site, were tentatively identified and mapped to a total of eight proteins (Table 3; see also Fig. S1A to H in the supplemental material). Five of these phosphosites were identified exclusively by the combined IMAC-MOAC approach (experiment D). The remaining four sites were identified by the combined IMAC-MOAC process as part of an overlapping data set with at least one other phosphoanalysis method within this study (Table 3). Although neural networks are not yet available for archaeal protein phosphosite predictions based on the limited data set available for this domain, many of the putative phosphosites identified in this study had NetPhos scores above the threshold of 0.5, which is based on eukaryotic phosphosites.

TABLE 3.

Putative phosphosites identified by MS-MSa

| ORF no. GenBank | Predicted function and/or description | Strainb | Expt | MOWSE (P > 95) | Total no. of peptidesc | NetPhos scored | Peptide E value | Peptide rank | Phosphopeptide sequence (phosphorylation site)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVO_0349 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit A′ | Both | B, D | 60 | 11 | 0.962 | 1.4 e-4 | 1 | LSLTDEEADEpYRDK (Y117) |

| HVO_0806 | Pyruvate kinase | GG102 | A to D | 83 | 13 | 0.867 | 1.9 e-3 | 1 | AGMpTGYPALVAR (T533) |

| HVO_A0579 | Branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter, ATPase | DS70 | D | 34 | 7 | 0.014 | 0.16 | 1 | MpSADETNAQSVDDPDADIDRDGER (S2) |

| HVO_1916 | TrkA-domain membrane protein | DS70 | D | 79 | 6 | 0.880 | 0.53 | 1 | LIGRpTIR (T578) |

| HVO_0001 | Cdc6, Orc | GG102 | D | 45 | 8 | 0.350 | 0.97 | 2 | SGDDTLYNLpSRMNSELDNSR (S321) |

| HVO_C0059 | Hypothetical protein | DS70 | D | 32 | 3 | 0.614, 0.802 | 0.99 | 1 | TSpSMQpTR (S136, T139) |

| HVO_2700 | Cdc48-like AAA+ ATPase | Both | B, C | 171 (DS70), 252 (GG102) | 18 (DS70), 17 (GG102) | 0.026 | 2.0 | 1 | IDGPNDGpTAIAR (T45) |

| HVO_A0206 | Conserved protein | DS70 | B, D | 101 | 8 | 0.888 | 2.8 | 1 | VEDVpSKLR (S88) |

See footnotes to Table 2 for ORF numbers, experiment designations, and MOWSE scores.

Strain in which the phosphopeptide was detected.

Total number of peptides detected by MS per protein identified as phosphorylated.

The NetPhos score produces neural network predictions for serine, threonine, and tyrosine phosphorylation sites based on eukaryotic proteins. The output score values range from 0.0 to 1.0, where values above 0.5 are assigned as putative phosphorylation sites.

A lowercase letter “p” precedes each residue proposed to be modified by phosphorylation. Phosphorylation sites are numbered according to the residue position of the polypeptide, deduced from the genome sequence.

Among the H. volcanii phosphoproteins identified, the Cdc48-related AAA+ ATPase (HVO_2700), which was more abundant in GG102 enriched fractions than in DS70 based on spectral counting, was represented by two identical phosphorylated peptides occurring in separate experiments for both strains (Table 3). Both inclusive and exclusive y ions and internal ion fragments containing a phosphorylated Thr45 residue were identified (numbering throughout is based on the deduced polypeptide sequence [see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material]). Similarly, a protein of unknown function (HVO_A0206) was also represented by duplicate peptides phosphorylated at Ser88 in multiple experiments (Table 3). Although the function of this ORF is unknown, it is transcribed in the same orientation as two genes encoding members of the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) family of proteins, which were identified by MS-MS as common to GG102 and DS70. A DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit A′ (RpoA′) was determined to have a phosphomodification at Tyr117 (Table 3). The discovery of the Tyr117 phosphosite, which had the highest NetPhos score (0.962) and the lowest expect value (1.4 e-4) of the phosphosites identified, was supported by the appearance of three separate internal fragment ions containing the modified tyrosine residue as well as an inclusive and exclusive y-ion series (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Other phosphoproteins included a Cdc6-1/Orc1-1 ortholog (HVO_0001) and pyruvate kinase (Table 3). Although both proteins were common to DS70 and GG102 based on MS-MS identification, the phosphopeptides of these proteins were detected only in GG102 panA. The reason for the exclusive appearance of the latter phosphopeptides in the panA mutant strain remains to be determined; however, it does implicate the proteins corresponding to these phosphopeptides as potential proteasomal substrates that depend on their phosphorylation status for destruction. Phosphosites were also identified on components of membrane systems including an ATPase of an ABC-type transporter as well as an integral membrane protein with a TrkA (NAD-binding) domain (Table 3). A hypothetical protein (HVO_C0059) was also identified as a putative phosphoprotein based on the detection of one doubly modified peptide fragment at residues Ser136 and Thr139 (Table 3).

Many of the phosphorylated proteins identified and listed in Table 3 are supported by evidence of the phosphorylation and proteasome-mediated destruction of their orthologs. For example, eukaryal RNA polymerases II and III are phosphorylated at tyrosine, serine, and/or threonine residues (23, 49), and ubiquitin E3 ligase Wwp2 targets the Rpb1 subunit of RNA polymerase II (related to H. volcanii RpoA′) for destruction by 26S proteasomes (37). Eukaryal and archaeal Cdc6 proteins undergo autophosphorylation at serine residues as a presumed means of regulating their DNA helicase loading activity (10, 16). Furthermore, the ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated destruction of Cdc6 in both mammalian and yeast cells has been observed and is proposed to be a mechanism for uncoupling DNA replication and cell division as part of a preprogrammed cell death response (4). Cdc48/p97/VCP proteins undergo Akt-mediated phosphorylation at multiple sites as a mode of ubiquitinated protein substrate release to facilitate degradation by proteasomes (31). In addition, these AAA+ ATPase proteins are phosphorylated by DNA-protein kinase at serine residues as part of a proposed mechanism to enable chaperone activity and to aid in DNA repair (40).

Conclusions.

Based on the results of this study, a global increase in the number of phosphoproteins appears to occur in a panA mutant compared to wild-type cells. Although several of the proteins enriched and identified as exclusive to GG102 panA are likely involved in phosphorus assimilation and metabolism and thus may bind phosphate noncovalently, this alone cannot account for the large-scale difference in phosphoprotein staining between the panA mutant and its parent. Therefore, we propose that the phosphorylation of protein substrates may facilitate their recognition for proteasome-mediated destruction in organisms for which traditional ubiquitination pathways are absent (e.g., archaea, actinomycetes). It is also possible that the observed changes in phosphoprotein content reflect a secondary effect of the maintained presence of a kinase or enhanced digestion of a phosphatase.

It has been demonstrated in eukaryotes that protein phosphorylation can serve as a precursor to ubiquitin tagging and subsequent degradation by 26S proteasomes (26, 39). Furthermore, phosphorylation of conserved sequences rich in proline, glutamic and aspartic acids, serine, and threonine (PEST sequences) is a well-known example of posttranslational modification as a destabilizing force on substrate proteins (15, 43). The link between protein phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation is also supported through the function of accessory structures such as the COP9 signalosome, which has been implicated as a coordinator of protein kinases and ubiquitin ligases in plant systems (18).

The predominant proteins identified as exclusive to the panA mutant GG102 (versus DS70) were linked to protein folding, Fe-S cluster assembly, oxidative stress response, and phosphorus assimilation and polyphosphate synthesis. A number of additional differences in transcription and signal transduction proteins (e.g., OsmC, BolA, Cmi2) were also observed between these two strains, and these, together with the growth defect, suggest that the panA mutant is undergoing stress and accumulating polyphosphate. Consistent with this, a distant relative of PanA, the ATPase ring-forming complex of mycobacteria, is presumed to associate with 20S proteasomes and serve as a defense against oxidative or nitrosative stress (9). Proteasomal inhibition has also been shown to hypersensitize differentiated neuroblastoma cells to oxidative damage (36). Interestingly, a polyphosphate-Lon protease complex is proposed in the adaptation of E. coli to amino acid starvation (34). Whether archaeal proteasomes are linked to polyphosphate remains to be determined; however, short-chain polyphosphates identical to those of Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been detected in H. volcanii cells grown under conditions of amino acid starvation (47).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to S. Stevens, Jr., and S. McClung of the Proteomics Core (Interdisciplinary Center of Biotechnology Research, University of Florida, Gainesville) for assistance with MS-MS protein analysis. Thanks also to A. Hartman, J. Eisen, and The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) for communication of the H. volcanii DS2 genome sequence. Thanks also to M. L. Dyall-Smith for supplying H. volcanii DS70 and plasmid pMDS99.

This research was funded in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM057498) and Department of Energy (DE-FG02-05ER15650).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 October 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allers, T., H. P. Ngo, M. Mevarech, and R. G. Lloyd. 2004. Development of additional selectable markers for the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii based on the leuB and trpA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70943-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antelmann, H., C. Scharf, and M. Hecker. 2000. Phosphate starvation-inducible proteins of Bacillus subtilis: proteomics and transcriptional analysis. J. Bacteriol. 1824478-4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold, I., and T. Langer. 2002. Membrane protein degradation by AAA proteases in mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 159289-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchard, F., M. E. Rusiniak, K. Sharma, X. Sun, I. Todorov, M. M. Castellano, C. Gutierrez, H. Baumann, and W. C. Burhans. 2002. Targeted destruction of DNA replication protein Cdc6 by cell death pathways in mammals and yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 131536-1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blom, N., S. Gammeltoft, and S. Brunak. 1999. Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J. Mol. Biol. 2941351-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, M. R., and A. Kornberg. 2004. Inorganic polyphosphate in the origin and survival of species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10116085-16087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cline, S. W., W. L. Lam, R. L. Charlebois, L. C. Schalkwyk, and W. F. Doolittle. 1989. Transformation methods for halophilic archaebacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 35148-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condò, I., D. Ruggero, R. Reinhardt, and P. Londei. 1998. A novel aminopeptidase associated with the 60 kDa chaperonin in the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Mol. Microbiol. 29775-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darwin, K. H., S. Ehrt, J. C. Gutierrez-Ramos, N. Weich, and C. F. Nathan. 2003. The proteasome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for resistance to nitric oxide. Science 3021963-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Felice, M., L. Esposito, B. Pucci, F. Carpentieri, M. De Falco, M. Rossi, and F. M. Pisani. 2003. Biochemical characterization of a CDC6-like protein from the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Biol. Chem. 27846424-46431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eichler, J., and M. W. Adams. 2005. Posttranslational protein modification in Archaea. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69393-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ficarro, S. B., M. L. McCleland, P. T. Stukenberg, D. J. Burke, M. M. Ross, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and F. M. White. 2002. Phosphoproteome analysis by mass spectrometry and its application to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Biotechnol. 20301-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer, R. J., S. Oehmcke, U. Meyer, M. Mix, K. Schwarz, T. Fiedler, and H. Bahl. 2006. Transcription of the pst operon of Clostridium acetobutylicum is dependent on phosphate concentration and pH. J. Bacteriol. 1885469-5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick, T. B., N. Amrhein, and P. Macheroux. 2003. Characterization of YqjM, an Old Yellow Enzyme homolog from Bacillus subtilis involved in the oxidative stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 27819891-19897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Alai, M. M., M. Gallo, M. Salame, D. E. Wetzler, A. A. McBride, M. Paci, D. O. Cicero, and G. Prat-Gay. 2006. Molecular basis for phosphorylation-dependent, PEST-mediated protein turnover. Structure 14309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabowski, B., and Z. Kelman. 2001. Autophosphorylation of archaeal Cdc6 homologues is regulated by DNA. J. Bacteriol. 1835459-5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grangeasse, C., A. J. Cozzone, J. Deutscher, and I. Mijakovic. 2007. Tyrosine phosphorylation: an emerging regulatory device of bacterial physiology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 3286-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harari-Steinberg, O., and D. A. Chamovitz. 2004. The COP9 signalosome: mediating between kinase signaling and protein degradation. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 5185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huber, S. C. 2007. Exploring the role of protein phosphorylation in plants: from signalling to metabolism. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 3528-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huisman, G. W., and R. Kolter. 1994. Sensing starvation: a homoserine lactone-dependent signaling pathway in Escherichia coli. Science 265537-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humbard, M. A., S. M. Stevens, Jr., and J. A. Maupin-Furlow. 2006. Posttranslational modification of the 20S proteasomal proteins of the archaeon Haloferax volcanii. J. Bacteriol. 1887521-7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jentsch, S., and S. Rumpf. 2007. Cdc48 (p97): a “molecular gearbox” in the ubiquitin pathway? Trends Biochem. Sci. 326-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jing, Y., Z. Song, M. Wang, W. Tang, S. Hao, and X. Zeng. 2005. c-Abl tyrosine kinase regulates c-fos gene expression via phosphorylating RNA polymerase II. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 437199-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaczowka, S. J., and J. A. Maupin-Furlow. 2003. Subunit topology of two 20S proteasomes from Haloferax volcanii. J. Bacteriol. 185165-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karadzic, I. M., and J. A. Maupin-Furlow. 2005. Improvement of two-dimensional gel electrophoresis proteome maps of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. Proteomics 5354-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karin, M., and Y. Ben Neriah. 2000. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-κB activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18621-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennelly, P. J. 2003. Archaeal protein kinases and protein phosphatases: insights from genomics and biochemistry. Biochem. J. 370373-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirkland, P. A., J. Busby, S. Stevens, Jr., and J. A. Maupin-Furlow. 2006. Trizol-based method for sample preparation and isoelectric focusing of halophilic proteins. Anal. Biochem. 351254-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkland, P. A., C. J. Reuter, and J. A. Maupin-Furlow. 2007. Effect of proteasome inhibitor clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone on the proteome of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. Microbiology 1532271-2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein, C., C. Garcia-Rizo, B. Bisle, B. Scheffer, H. Zischka, F. Pfeiffer, F. Siedler, and D. Oesterhelt. 2005. The membrane proteome of Halobacterium salinarum. Proteomics 5180-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein, J. B., M. T. Barati, R. Wu, D. Gozal, L. R. Sachleben, Jr., H. Kausar, J. O. Trent, E. Gozal, and M. J. Rane. 2005. Akt-mediated valosin-containing protein 97 phosphorylation regulates its association with ubiquitinated proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 28031870-31881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krogh, A., B. Larsson, G. von Heijne, and E. L. Sonnhammer. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305567-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuo, M. S., K. P. Chen, and W. F. Wu. 2004. Regulation of RcsA by the ClpYQ (HslUV) protease in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 150437-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuroda, A. 2006. A polyphosphate-Lon protease complex in the adaptation of Escherichia coli to amino acid starvation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lesniak, J., W. A. Barton, and D. B. Nikolov. 2003. Structural and functional features of the Escherichia coli hydroperoxide resistance protein OsmC. Protein Sci. 122838-2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lev, N., E. Melamed, and D. Offen. 2006. Proteasomal inhibition hypersensitizes differentiated neuroblastoma cells to oxidative damage. Neurosci. Lett. 39927-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, H., Z. Zhang, B. Wang, J. Zhang, Y. Zhao, and Y. Jin. 2007. Wwp2-mediated ubiquitination of the RNA polymerase II large subunit in mouse embryonic pluripotent stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 275296-5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, L., Q. Li, L. Rohlin, U. Kim, K. Salmon, T. Rejtar, R. P. Gunsalus, B. L. Karger, and J. G. Ferry. 2007. Quantitative proteomic and microarray analysis of the archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans grown with acetate versus methanol. J. Proteome Res. 6759-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin, D. I., O. Barbash, K. G. Kumar, J. D. Weber, J. W. Harper, A. J. Klein-Szanto, A. Rustgi, S. Y. Fuchs, and J. A. Diehl. 2006. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin D1 by the SCF(FBX4-αB crystallin) complex. Mol. Cell 24355-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livingstone, M., H. Ruan, J. Weiner, K. R. Clauser, P. Strack, S. Jin, A. Williams, H. Greulich, J. Gardner, M. Venere, T. A. Mochan, R. A. DiTullio, Jr., K. Moravcevic, V. G. Gorgoulis, A. Burkhardt, and T. D. Halazonetis. 2005. Valosin-containing protein phosphorylation at Ser784 in response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 657533-7540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Majdalani, N., and S. Gottesman. 2005. The Rcs phosphorelay: a complex signal transduction system. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59379-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ptacek, J., and M. Snyder. 2006. Charging it up: global analysis of protein phosphorylation. Trends Genet. 22545-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rechsteiner, M., and S. W. Rogers. 1996. PEST sequences and regulation by proteolysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21267-271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reuter, C. J., S. J. Kaczowka, and J. A. Maupin-Furlow. 2004. Differential regulation of the PanA and PanB proteasome-activating nucleotidase and 20S proteasomal proteins of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. J. Bacteriol. 1867763-7772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudolph, J., N. Tolliday, C. Schmitt, S. C. Schuster, and D. Oesterhelt. 1995. Phosphorylation in halobacterial signal transduction. EMBO J. 144249-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santos, J. M., M. Lobo, A. P. Matos, M. A. De Pedro, and C. M. Arraiano. 2002. The gene bolA regulates dacA (PBP5), dacC (PBP6) and ampC (AmpC), promoting normal morphology in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 451729-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scoarughi, G. L., C. Cimmino, and P. Donini. 1995. Lack of production of (p)ppGpp in Halobacterium volcanii under conditions that are effective in the eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 17782-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma, N., S. Marguerat, S. Mehta, S. Watt, and J. Bahler. 2006. The fission yeast Rpb4 subunit of RNA polymerase II plays a specialized role in cell separation. Mol. Genet. Genomics 276545-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solodovnikova, A. S., N. A. Merkulova, A. A. Perova, and V. M. Sedova. 2005. Subunits of human holoenzyme of DNA dependent RNA polymerase III phosphorylated in vivo. Tsitologiia 471082-1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinberg, T. H., B. J. Agnew, K. R. Gee, W. Y. Leung, T. Goodman, B. Schulenberg, J. Hendrickson, J. M. Beechem, R. P. Haugland, and W. F. Patton. 2003. Global quantitative phosphoprotein analysis using multiplexed proteomics technology. Proteomics 31128-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tahara, M., A. Ohsawa, S. Saito, and M. Kimura. 2004. In vitro phosphorylation of initiation factor 2α (aIF2α) from hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 135479-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tam, L. T., H. Antelmann, C. Eymann, D. Albrecht, J. Bernhardt, and M. Hecker. 2006. Proteome signatures for stress and starvation in Bacillus subtilis as revealed by a 2-D gel image color coding approach. Proteomics 64565-4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tatusov, R. L., M. Y. Galperin, D. A. Natale, and E. V. Koonin. 2000. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2833-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vener, A. V. 2007. Environmentally modulated phosphorylation and dynamics of proteins in photosynthetic membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767449-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walsh, C. T., S. Garneau-Tsodikova, and G. J. Gatto, Jr. 2005. Protein posttranslational modifications: the chemistry of proteome diversifications. Angew. Chem. Int. ed. Engl. 447342-7372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wendoloski, D., C. Ferrer, and M. L. Dyall-Smith. 2001. A new simvastatin (mevinolin)-resistance marker from Haloarcula hispanica and a new Haloferax volcanii strain cured of plasmid pHV2. Microbiology 147959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.