Abstract

Breakdown of the skin barrier requires the recognition of and rapid responses to invading pathogens. Since wounding usually also affects endothelial intactness, the expression of receptors of the Toll-like family involved in pathogen recognition in human skin vessel endothelia was examined. We found that human skin-derived microvascular endothelial cells can express all 10 Toll-like receptors (TLRs) currently known and will respond to respective ligands. Using immortalized skin-derived (HMEC-1) and primary dermal endothelial cells (HDMEC), we screened for TLR expression by real-time PCR. Endothelial cells express 7 (for HDMEC) and 8 (for HMEC-1) of the 10 known human TLRs under resting conditions but can express all 10 receptors in proinflammatory conditions. To provide evidence of TLR functionality, endothelial cells were challenged with TLR ligands, and after the TLR downstream signaling, MyD88 recruitment as well as early (interleukin-8 [IL-8] release) and late immune markers (inducible nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression) were monitored. Surprisingly, the responses observed were not uniform but were highly specific depending on the respective TLR ligand. For instance, lipopolysaccharides highly increased IL-8 release, but CpG DNA induced significant suppression. Additionally, TLR-specific responses were found to differ between resting and activated endothelial cells. These results show that human skin-derived endothelial cells can function as an important part of the innate immune response, can actively sense pathogen-associated molecular patterns, and can mount an increased or reduced inflammatory signal upon exposure to any of the currently known TLR ligands. Moreover, we also show here that proinflammatory conditions may affect TLR expression in a specific and nonuniform pattern.

Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular structures by cells of the innate immune defense via the various Toll-like receptors (TLRs) represents a key event in mounting an inflammatory response and initiating an immune defense. A variety of bacterial, viral, and fungal components are known ligands for these receptors, and their binding initiates proinflammatory responses (19, 23). In humans, 10 different TLRs currently are known, and their expression and function have been extensively characterized mostly with macrophages and dendritic cell populations.

Mounting evidence points to a significant role for vascular endothelial cells as important players in innate immunity and in controlling the host responses to pathogens. Thus, endothelial cells are active producers of various cytokines and chemokines and also are able to release the signaling molecule nitric oxide, produced by the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which has a strong effect on the local circulation and on wound-healing processes (21, 25, 26). Further, endothelial cells can express various adhesion molecules, can present antigen due to their constitutive expression of major histocompatibility complex molecules, and also can actively induce tolerance by preferentially inducing a regulatory T-cell phenotype (3, 14, 15). Given these activities, it is of interest to know whether endothelial cells also actively participate in pathogen recognition, which, due to their blood-exposed location, would assign these cells a key role in the initial responses to pathogens that have reached the blood. Indeed, two earlier investigations have shown that endothelial cells express functional TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 (7, 18), and several studies hypothesize a contribution of endothelial cell activities induced via TLRs in pathological processes such as sepsis (4, 8), atherosclerosis (5, 24), and human immunodeficiency virus proliferation (6). In view of these observations, we asked whether primary human endothelial cells might also express TLRs other than the aforementioned and might contribute more broadly to pathogen recognition than has been acknowledged so far. Moreover, we also addressed the issue of endothelial TLR expression under proinflammatory conditions, as TLRs are known to occur in most of the diseases cited above and for which an endothelial involvement via TLR-mediated recognition of pathogen-associated patterns currently is being discussed.

With our results, we describe here that, indeed, endothelial cells do express most of the 10 TLRs in resting state and express all 10 receptors of this family under proinflammatory conditions. After the late TLR downstream signaling, we chose an increased interleukin-8 (IL-8) release and iNOS expression as readout parameters for receptor function. In doing so, we see that under resting conditions some of the TLRs expressed appear nonfunctional, while during inflammatory conditions all of the ligands induce increased IL-8 release or iNOS expression, indicating that signaling through some of the TLRs needs additional signals in endothelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Primary human dermal endothelial cells (HDMEC) were obtained from PromoCell (Heidelberg, Germany). Cells of three different donors were used (one child of 4 years and two children of 7 years, all male and of Caucasian origin). HDMEC were maintained in endothelial growth medium MV containing 0.4% endothelial cell growth supplement-human, 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 50 ng/ml amphotericin B, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (PromoCell). Cells were removed from plates by incubation with 1% trypsin-0.03% EDTA (PAA, Coelbe, Germany) at room temperature. The reaction was blocked with medium containing 20% FCS. HDMEC were seeded at a density of 7,500 cells/cm2. Experiments were carried out between the sixth and eighth population doubling.

Immortalized skin-derived endothelial cells (HMEC-1) were received from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA). For all experiments except immunofluorescence, cells were cultivated in MCDB 131 medium (Gibco-Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) containing 1× Glutamax I (Invitrogen), 10% FCS (PAA), 50 ng/ml amphotericin B, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (PromoCell). Cells were propagated using 1% trypsin-0.03% EDTA (PAA) at 37°C, and the digestion was stopped using medium containing 10% FCS. HMEC-1 were seeded at a density of 55,000 cells/cm2, and cells between passages 20 and 30 were used for assays.

Both cell types were cultured at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, and experiments were performed at a near-confluence state. Cell cultures were free of mycoplasma contamination, as verified by a VenorGeM mycoplasma PCR detection kit (Minerva Biolabs, Berlin, Germany).

Treatment with proinflammatory cytokines and TLR-specific ligands.

Cells were incubated with a triplet of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], IL-1β, and gamma interferon [IFN-γ]; 1,000 U/ml each; Strathmann Biotech, Hannover, Germany) for 18 or 24 h. TLR-specific ligands [Pam3Cys, 5 μg/ml; lipoteichoic acid (LTA), 10 μg/ml; poly(I:C), 50 μg/ml; lipopolysaccharide (LPS), 100 ng/ml; flagellin, 500 ng/ml; imiquimod, 10 μM; and CpG DNA, 1 μM] were applied for 6 h prior to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) or 24 h prior to PCR. For immunofluorescence assays, 50 μg/ml poly(I:C), 100 ng/ml LPS, and 1 μM CpG DNA were applied for 5 min, 10 min, or 4 h. LPS (from Escherichia coli O55:B5) and CpG DNA (S-oligodeoxynucleotide CpG-A; 5′-GGTGCATCGATGCAGGGGGG-3′) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany); imiquimod was purchased from Sequoia Research Products (Oxford, Great Britain); and Pam3Cys, LTA (from Staphylococcus aureus), poly(I:C), and flagellin (from Bacillus subtilis) were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA).

Immunofluorescence of MyD88.

For experiments using immunofluorescence, HMEC-1 were cultivated in MCDB 131 medium (Gibco-Invitrogen) containing 1× Glutamax I (Invitrogen), 10% FCS (PAA), 60 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (PAA), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Sigma), and 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany). HMEC-1 were seeded at a density of 18,500 cells/cm2 into an 8-well Lab-Tek chamber slide/cover glass (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL).

HMEC-1 were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Cells first were permeabilized for 10 min with 0.1% Triton X-100-PBS (PBST) and then blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBST for 1 h, followed by incubation with the first antibody (polyclonal anti-human MyD88 internal peptide [eBioscience, San Diego, CA]; 1:500 in 5% BSA-PBST) for 1 h. The second antibody, goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (heavy plus light chains), highly cross-absorbed and labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen), was diluted 1:250 in 5% BSA-PBST and incubated for 1 h. For nuclear staining, cells were treated with 10 μg Hoechst reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany)/ml of PBS for 10 min. Slides were covered in 0.1% 1, 4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO)-Mowiol. Optical analysis was performed using a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS laser-scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

Endotoxin blockage with PmB.

Where indicated, ligands were preincubated with polymyxin B sulfate salt (PmB; Sigma-Aldrich) in aqueous solution for 1 h at 4°C as a stock solution. For use in experiments, dilution with medium to a final concentration of 10 μg PmB/ml medium was performed.

Sandwich ELISA of IL-8.

The quantification of IL-8 release was performed with a DuoSet ELISA development system kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as described by the manufacturer's protocol. Aliquots of supernatants of HDMEC or HMEC-1 cultures were collected 6 h after the addition of TLR-specific ligands. The reaction with substrate solution was stopped after 5 min. The optical density was measured using a plate reader (FLUOstar OPTIMA; BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany) on Maxisorp plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark).

Preparation of RNA and RT reactions.

Total RNA from HDMEC or HMEC-1 was extracted by using the RNeasy Mini kit and RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). One microgram of RNA was used for each cDNA synthesis (Omniscript RT kit; Qiagen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with both oligo(dT) (Sigma-Genosys, Steinheim, Germany) and random primers (Operon Biotechnologies, Huntsville, AL) for two-step real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR. Oligo(dT) primers were used only for conventional two-step RT-PCR. All steps of RT were performed by following the manufacturer's protocol.

Real-time PCR.

For quantitative real-time PCR, the concentrations of cDNA and primer sets applied are given in Tables 1 and 2. The sequences of oligonucleotides were taken from previous publications (18s [13], TLR1 to TLR8 [27], TLR9 [1], and TLR10 [2]) or were designed by using Primer Express 2.0 (TLR7II and iNOS; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All primers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The specificity of oligonucleotides was verified by a homology search of the human genome using BLAST (NCBI). Additionally, the specificity was confirmed by performing dissociation curves, and specific PCR products were further verified using agarose electrophoresis.

TABLE 1.

Accession numbers, primer sets, and the expected size of amplifying productsa

| Gene | Accession no. | Primer

|

Fragment size (in bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense | Antisense | |||

| TLR1 | NM_003263 | 5′-CAG TGT CTG GTA CAC GCA TGG T-3′ | 5′-TTT CAA AAA CCG TGT CTG TTA AGA GA-3′ | 105 |

| TLR2 | NM_003264 | 5′-GGC CAG CAA ATT ACC TGT GTG-3′ | 5′-AGG CGG ACA TCC TGA ACC T-3′ | 67 |

| TLR3 | NM_003265 | 5′-CCT GGT TTG TTA ATT GGA TTA ACG A-3′ | 5′-TGA GGT GGA GTG TTG CAA AGG-3′ | 82 |

| TLR4 | U88880 | 5′-CAG AGT TTC CTG CAA TGG ATC A-3′ | 5′-GCT TAT CTG AAG GTG TTG CAC AT-3′ | 85 |

| TLR5 | NM_003268 | 5′-TGC CTT GAA GCC TTC AGT TAT G-3′ | 5′-CCA ACC ACC ACC ATG ATG AG-3′ | 77 |

| TLR6 | NM_006068 | 5′-GAA GAA GAA CAA CCC TTT AGG ATA GC-3′ | 5′-AGG CAA ACA AAA TGG AAG CTT-3′ | 88 |

| TLR7 (HDMEC) | NM_016562 | 5′-CAA CCA GAC CTC TAC ATT CCA TTT TGG AA-3′ | 5′-TCT TCA GTG TCC ACA TTG GAA AC-3′ | 68 |

| TLR7II (HMEC-1) | NM_016562 | 5′-TTT ACC TGG ATG GAA ACC AGC TA-3′ | 5′-TCA AGG CTG AGA AGC TGT AAG CTA-3′ | 73 |

| TLR8 | AF245703 | 5′-TTA TGT GTT CCA GGA ACT CAG AGA A-3′ | 5′-TAA TAC CCA AGT TGA TAG TCG ATA AGT TTG-3′ | 83 |

| TLR9 | AF245704 | 5′-CCA CCC TGG AAG AGC TAA ACC-3′ | 5′-GCC GTC CAT GAA TAG GAA GC-3′ | 161 |

| TLR10 | AF296673 | 5′-GCC CAA GGA TAG GCG TAA ATG-3′ | 5′-ATA GCA GCT CGA AGG TTT GCC-3′ | 54 |

| iNOS | AF068236 | 5′-GGT GGA AGC GGT AAC AAA GG-3′ | 5′-TGC TTG GTG GCG AAG ATG A-3′ | 81 |

| 18S | X03205 | 5′-CAT GGT GAC CAC GGG TGA C-3′ | 5′-TTC CTT GGA TGT GGT AGC CG-3′ | 79 |

TABLE 2.

Amounts of reverse-transcribed mRNA for each TLR gene used in real-time PCR

| Cell type | Amt (ng) of mRNA for gene:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | TLR2 | TLR3 | TLR4 | TLR5 | TLR6 | TLR7 | TLR8 | TLR9 | TLR10 | |

| HMEC-1 | 20 | 100 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| HDMEC | 100 | 4 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

The detection of amplification was performed by using a QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen) or a power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI PRISM 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The running protocol was set to 95°C for 15 min and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s.

In setting up the amplifying conditions, a pool of the various treated HDMEC was used that expressed all 10 TLRs. The expression of TLR2 and TLR4 in HDMEC is high, requiring 4 ng of reverse-transcribed cDNA to obtain mean threshold cycle (CT) values of 25, whereas the other TLR genes require 100 ng of cDNA as a template. Here, mean CT values from 25 to 36.5 were determined.

Using HMEC-1 mRNA, the conditions of real-time PCR were adapted from those for the setting of primary cells. Relative to those for HDMEC, the amounts of cDNA had to be corrected for TLR1 (20 ng as the template concentration) and TLR2 (100 ng); otherwise, the conditions were identical.

Conventional two-step RT-PCR of iNOS and GAPDH.

The extraction of total RNA and RT was performed as described above. PCR was performed by using a Taq PCR core kit (Qiagen), as described in the manufacturer's manual, with 250 ng cDNA. Primer sets for iNOS and GAPDH, as well as the cycler protocol, are given in Table 3. Two-step RT-PCR of iNOS and GAPDH was performed using a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems) exactly as described above. The documentation of the agarose gel was evaluated by Kodak Digital Science 1D software (New Haven, CT).

TABLE 3.

Accession numbers and primer sets, expected sizes of amplifying products, and PCR cycling conditions for two-step RT-PCR of iNOS and GAPDH

| Gene | Accession no. | Primer sequence

|

Protocol | Size of fragment (in bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense | Antisense | ||||

| iNOS | AF068236 | 5′-ATG CCA GAT GGC AGC ATC AGA-3′ | 5′-TTT CCA GGC CCA TTC TCC TGC-3′ | 72°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; 34 cycles | 379 |

| GAPDH | NM_002046 | 5′-CAA CTA CAT GGT TTA CAT GTT CC-3′ | 5′-GGA CTG TGG TCA TGA GTC CT-3′ | 72°C for 15 s, 57°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; 17 cycles | 416 |

Statistics.

Statistical significance was assessed with two-tailed Student's t tests, and results are given as the means ± standard deviations. A P of <0.05 is considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TLR gene expression in human endothelial cells.

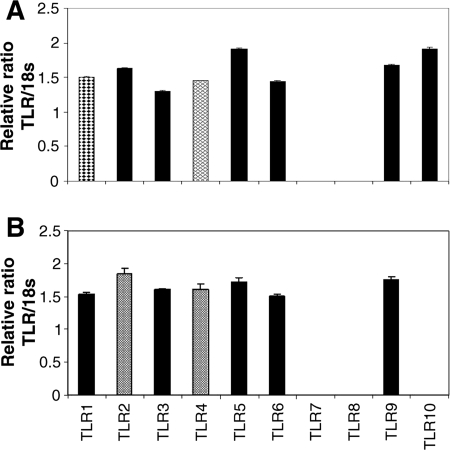

The expression of the 10 currently known human TLRs on the gene level initially was assessed in HMEC-1. Therefore, cultures of HMEC-1 were grown to near confluence and lysed, and their RNA was isolated, reverse transcribed, and analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR as described in Materials and Methods. In addition to TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9 expression, which has been demonstrated previously (7, 18), we also found that TLR6 and TLR10 were expressed. Cells were negative for TLR7 and TLR8 (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Resting endothelial cells express 8 out of 10 TLRs. The relative ratio of the TLR gene to 18S mRNA level is given as evidence for TLR expression in resting endothelia. The amounts of cDNA used for two-step real-time RT-PCR are given in Table 2. (A) In the endothelial line HMEC-1, all TLR genes except TLR7 and TLR8 are expressed. (B) In primary skin endothelia, all TLR genes except TLR7, TLR8, and TLR10 are found (n = 3).

We observe the same TLR expression patterns in resting HDMEC as those observed in HMEC-1, excluding the expression of TLR10 (Fig. 1B). In addition, the mRNA levels of the different TLR genes in HDMEC are comparable to those of immortalized endothelial cells, with a few exceptions (Table 2). TLR1 is expressed at a lower level and TLR2 is expressed at a higher level in HDMEC than in immortalized endothelial cells.

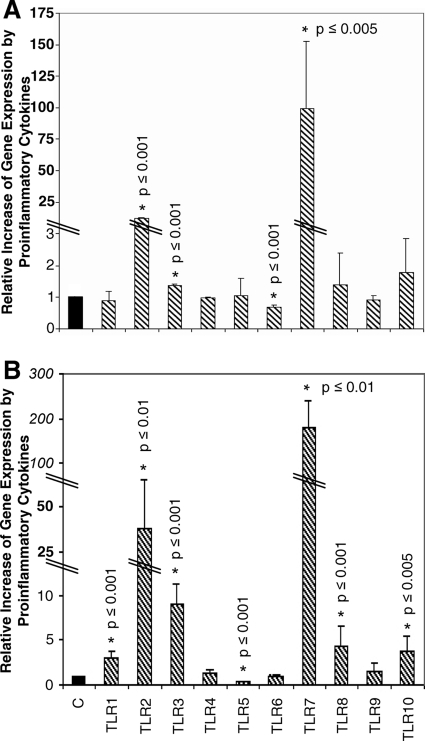

We next investigated the expression of TLR genes under proinflammatory conditions. First, HMEC-1 were activated with proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ; 1,000 U/ml each) for 18 h. This challenge leads to the expression of all 10 known TLR genes. We found significant increases of TLR2 (by a factor of 13.8 ± 0.9) and TLR3 (by a factor of 1.4 ± 0.03), a significant decrease of TLR6 (by a factor of 0.7 ± 0.04), de novo expression of TLR7 and TLR8, and constitutive expression of TLR1, TLR4, TLR5, TLR9, and TLR10 (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Activated endothelial cells express all 10 TLRs. Cells were incubated with a triplet of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ; 1,000 U/ml each) for 18 h. Cells then were lysed, RNA was isolated, and a two-step real-time RT-PCR was performed. Data obtained are calculated to the corresponding level of TLR gene expression (normalized to 1) in nonactivated cells. (A) In HMEC-1, we find that TLR2 and TLR3 are significantly upregulated and TLR7 and TLR8 are expressed de novo. TLR6 is significantly downregulated, whereas TLR1, TLR4, TLR5, TLR9, and TLR10 are constitutively expressed. (B) In primary cells, TLR1, TLR2, and TLR3 are significantly upregulated, and TLR7, TLR8, and TLR10 are expressed de novo. TLR5 is significantly downregulated, whereas TLR4, TLR6, and TLR9 are constitutively expressed (n = 3).

In identically challenged primary endothelial cells, we observed the upregulation of TLR1 (a factor of 3.1 ± 0.6), TLR2 (a factor of 38.3 ± 27), and TLR3 (a factor of 9.1 ± 2) and de novo expression of TLR7, TLR8, and TLR10. TLR4, TLR6, and TLR9 display a constitutive and unchanged expressional mode. Interestingly, in the primary cells, TLR5 is significantly downregulated (by a factor of 0.35 ± 0.07) (Fig. 2B).

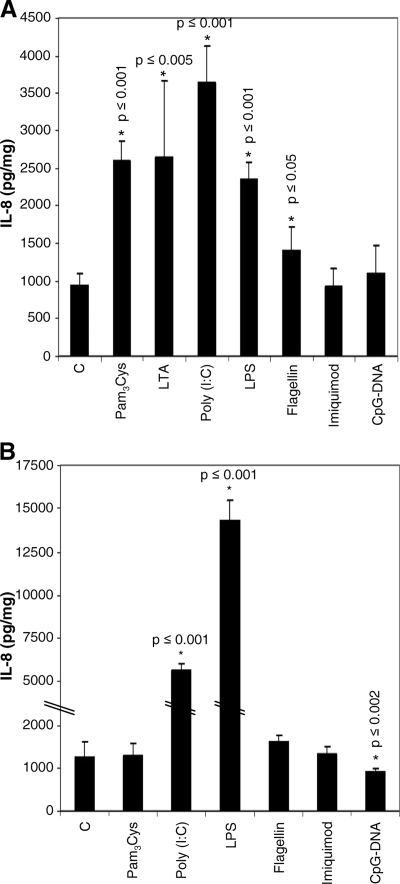

Functional expression of TLRs: modulation of IL-8 release by addition of TLR-specific ligands.

To investigate whether the TLRs expressed in HMEC-1 are functional proteins, cells were incubated with TLR-specific ligands [TLR2, Pam3Cys (5 μg/ml) and LTA (10 μg/ml); TLR3, poly(I:C) (50 μg/ml); TLR4, LPS (100 ng/ml); TLR5, flagellin (500 ng/ml); TLR7, imiquimod (10 μM); and TLR9, CpG DNA (1 μM)] for 6 h, and an IL-8 ELISA was performed using the supernatants of the cell cultures. The incubation time was chosen on the basis of the maximal responses to LPS (not shown). In detecting IL-8 protein in resting cells, we found a significant response to Pam3Cys (2,598 pg/mg ± 268 pg/mg; a factor of 2.8), LTA (2,656 pg/mg ± 999 pg/mg; a factor of 2.8), poly(I:C) (3,650 pg/mg ± 465 pg/mg; a factor of 3.9), LPS (2,371 pg/mg ± 206 pg/mg; a factor of 2.5), and flagellin (1,401 pg/mg ± 322 pg/mg; a factor of 1.5) relative to that of basal IL-8 production (939 pg/mg ± 170 pg/mg). No effects were observed for imiquimod or CpG DNA (Fig. 3A). However, with increased concentrations of CpG DNA, a suppressive effect was seen (5 μM CpG DNA resulted in a reduction of IL-8 to 75% the normal level; 10 μM CpG DNA resulted in a reduction of IL-8 to 50% the normal level) (9).

FIG. 3.

Increases in endothelial IL-8 release prove the functional expression of TLRs. Cells were incubated with TLR-specific ligands for 6 h, and supernatants were analyzed for their IL-8 contents. (A) In HMEC-1, we found significant increases of IL-8 production with Pam3Cys, LTA, poly(I:C), LPS, and flagellin. (B) In primary cells, significant increases of IL-8 production with poly(I:C) and LPS were seen, and a significant decrease was seen with CpG DNA (n = 3 to 4).

For nonactivated HDMEC, we also found a significantly increased IL-8 release with poly(I:C) (5,624 pg/mg ± 769 pg/mg; a factor of 4.5) and LPS (14,244 pg/mg ± 2456 pg/mg; a factor of 11.3) but a decrease below the level of constitutive IL-8 production with CpG DNA (910 pg/mg ± 94 pg/mg; a factor of 0.7) compared to that of resting cells without additives (1,262 pg/mg ± 359 pg/mg). The other ligands used here do not modify IL-8 production (Fig. 3B).

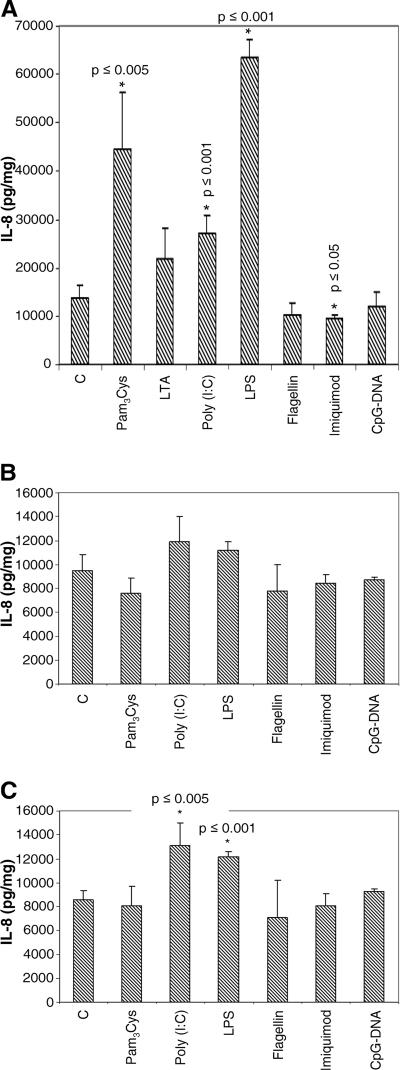

Upon activation with a triplet of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ; 1,000 U/ml each), HMEC-1 respond differently to the respective ligand incubations. In this setting, cells produce significantly larger amounts of IL-8 when incubated with Pam3Cys (44,704 pg/mg ± 11,590 pg/mg), poly(I:C) (27,188 pg/mg ± 3,559 pg/mg), and LPS (63,482 pg/mg ± 3,898 pg/mg) than do activated cells only (13,824 pg/mg ± 2,480 pg/mg). The challenge of cells with imiquimod leads to a significant reduction of IL-8 release (9,752 pg/mg ± 709 pg/mg). The remaining ligands used in these experiments do not show any modulating effects (Fig. 4A). Activated HDMEC show a highly and significantly increased IL-8 release (9,503 pg/mg ± 1,347 pg/mg; a factor of 7.5) compared to those of resident controls, and roughly the same level of IL-8 synthesis also is seen after activation with two cytokines (IL-1β and IFN-γ; 1,000 U/ml each) (8,563 pg/mg ± 786 pg/mg) (Fig. 3B and 4B and C). Additional incubation with TLR-specific ligands leads to no significant modulation of IL-8 production when cells are activated with the three cytokines (8,563 pg/mg ± 786 pg/mg) (Fig. 4B), but we found a significant increase in IL-8 secretion for poly(I:C) (13,118 pg/mg ± 1,868 pg/mg) and LPS (12,166 pg/mg ± 457 pg/mg) if the cells were pretreated with IL-1β and IFN-γ only (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

With activated endothelial cells, the high level of IL-8 synthesis is further augmented. Cells were incubated with a triplet (A and B) or a doublet (C) of proinflammatory cytokines (as described in the legend to Fig. 2) for 24 h, and TLR-specific ligands then were added for 6 h. (A) In HMEC-1, IL-8 release is 10 times higher than that in resting cells and is further and significantly increased upon challenge with Pam3Cys, poly(I:C), and LPS. Challenge with imiquimod leads to a significantly reduced level of IL-8 release in HMEC-1. (B) In HDMEC, activation with the cytokine triplet results in an increase of IL-8 formation by a factor of 7.5 (compared to that depicted in Fig. 3B), and no significant modulation of IL-8 production is seen after ligand addition. (C) When cells were incubated only with IL-1β and IFN-γ (1,000 U/ml each), an increase in IL-8 production of controls (column C) is seen that is similar to that described for panel B, but here a significantly increased IL-8 synthesis is seen after the addition of poly(I:C) and LPS (n = 3 to 4).

Functional expression of TLRs: modulation of iNOS expression by addition of TLR-specific ligands.

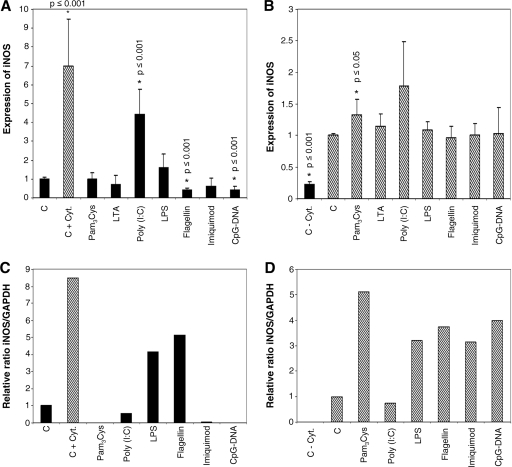

To further prove the functional expression of TLRs, we also examined the modulation of iNOS gene expression by two-step RT-PCR after incubating HMEC-1 as well as HDMEC with different TLR-specific ligands as described above. Resting HMEC-1 showed a low level of basal iNOS expression as detected by real-time PCR (CT of 33.5 with 100 ng cDNA). When challenged with TLR-specific ligands, HMEC-1 express increased levels of iNOS (by a factor of 4.6 ± 1.3) only when incubated with poly(I:C). Significant downregulation of basal iNOS expression was observed with flagellin (by a factor of 0.42 ± 0.12) and CpG DNA (a factor of 0.43 ± 0.2) (Fig. 5A). In resting HDMEC, iNOS mRNA is expressed at the detection limit, but upon the addition of LPS or flagellin, de novo expression of iNOS is seen. None of the other ligands resulted in the induction of iNOS expression in resting HDMEC (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Endothelial expression of iNOS also results from TLR ligand challenge. Nonactivated or activated cells were incubated with TLR-specific ligands for 24 h, and a two-step quantitative real-time RT-PCR (A and B) or a two-step RT-PCR and determination of band intensity (C and D) were performed to detect the expression of iNOS relative to those of 18S mRNA and GAPDH, respectively. Black bar, absence of cytokines; hatched bar, presence of cytokines; column C, control; column C + Cyt., control in the presence of cytokines; columnn C − Cyt., control in the absence of cytokines. (A) In control HMEC-1, borderline expression of iNOS is found (CT = 33.5). Only the addition of poly(I:C) results in the de novo synthesis of iNOS. Upon challenge with flagellin or CpG DNA, the basal expression of iNOS is significantly reduced. (B) When activated with a triplet of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ; 1,000 U/ml each [C + Cyt]), iNOS expression is significantly increased as expected, and the addition of specific ligands results in a further increase in iNOS expression only with Pam3Cys. (C) In control HDMEC-1, iNOS is not expressed, but the addition of LPS and flagellin results in the de novo synthesis of iNOS mRNA. (D) With activated primary cells (as described for panel B), de novo synthesis of iNOS is observed. An additional increase in iNOS expression is seen with all ligands except poly(I:C) (n = 1 to 4).

The activation of HMEC-1 by a triplet of proinflammatory cytokines in the absence of TLR ligands leads to the induction of iNOS expression, and this level is further increased by incubation with Pam3Cys only (by a factor of 1.3 ± 0.2) (Fig. 5B). When primary endothelial cells are activated with proinflammatory cytokines, we observe significant increases in iNOS expression upon challenge with Pam3Cys (by a factor of 5.1), LPS (a factor of 3.2), flagellin (a factor of 3.7), imiquimod (a factor of 3.1), and CpG DNA (a factor of 4.0). No further increase of iNOS expression is seen with poly(I:C) (Fig. 5D).

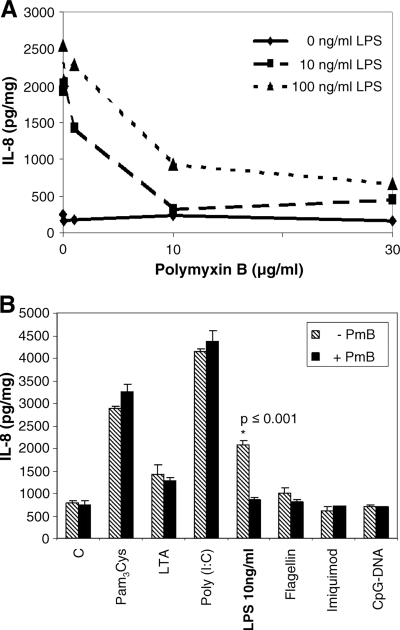

Endotoxin-free ligands lead to iNOS expression and IL-8 release.

To verify that the monitored iNOS expression and IL-8 release modulations are based upon ligand challenge and are not the result of endotoxin contamination, we first determined the optimal dose of PmB to block the endotoxin effect of LPS. We preincubated various concentrations of PmB (0 to 30 μg/ml) with two different concentrations of LPS (10 and 100 ng/ml) and measured IL-8 release. We observed that the effect of LPS (100 ng/ml, final concentration) can be blocked by more than 50% when pretreated with 10 μg/ml PmB. Using LPS at a concentration of 10 ng/ml, the effects can be completely blocked with PmB (Fig. 6A). Thus, preincubation of the respective ligands with PmB (10 μg/ml) will block effects resulting from endotoxin contaminations. We found that none of the ligands used contain measurable contaminations of endotoxin, since PmB effectively blocked the LPS response but did not interfere with reactions to any of the other ligands (Fig. 6B). Thus, none of the effects described are due to LPS contamination. In addition, basal levels of IL-8 release also were not suppressed by PmB, demonstrating the absence of LPS contamination in the culture medium.

FIG. 6.

Endothelial responses to ligands are not due to LPS contamination. (A) Different concentrations of LPS were preincubated with PmB at the concentrations shown. Cells then were treated with LPS-PmB combinations for 6 h, and the release of IL-8 was determined. A potent inhibition of the LPS-induced IL-8 formation is seen with 10 μg/ml PmB. (B) All ligands were preincubated with PmB (10 μg/ml, final concentration). Ligands were the same as those described for Fig. 3 to 5. HMEC-1 cells were incubated with the ligand-PmB mixture for 6 h, and then IL-8 release was determined. All ligands used (except LPS) are free of endotoxin contaminations (n = 2 to 4). Column C, samples without ligands.

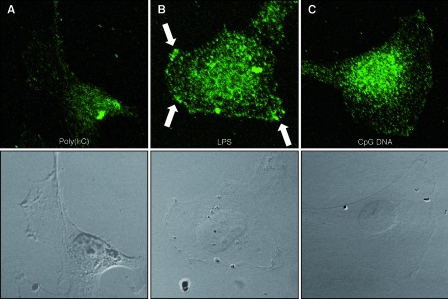

Specific and time-dependent recruitment of MyD88 to different cell compartments depending on the ligand used.

To further examine the functional binding of TLR-specific ligands to their corresponding receptors, HMEC-1 were incubated with LPS as well as CpG DNA, and endogenous MyD88 recruitment was monitored by immunofluorescence using laser-scanning microscopy. Poly(I:C) was used as a negative control, since it activates a MyD88-independent pathway. Three different time points (5 min, 10 min, and 4 h) were examined, and we found that incubation for 5 to 10 min led to the maximal MyD88 recruitment upon LPS or CpG DNA challenge. Upon the addition of LPS, MyD88 was recruited to the plasma membrane. The incubation of cells with CpG DNA leads to an accumulation of MyD88 at vesicles near the nucleus. Upon poly(I:C) challenge, MyD88 is located evenly throughout the cytoplasm exactly as in nonchallenged cells (Fig. 7). Thus, the recruitment of MyD88 is specific for the TLR ligands and further proves the functionality of the TLR signaling cascade in human endothelial cells.

FIG. 7.

Endothelial cells respond with endogenous MyD88 redistribution upon challenge with LPS or CpG DNA. HMEC-1 were incubated with poly(I:C) (negative control), LPS, and CpG DNA for 5 or 10 min. Cells were fixed and permeabilized and then were incubated with a polyclonal anti-human MyD88 antibody and an Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibody. Fluorescence was detected using a laser-scanning microscope. (A) Upon poly(I:C) challenge, MyD88 is evenly distributed in the cytoplasm, and no change in distribution relative to that of untreated controls was observed. (B) Upon LPS challenge, MyD88 is relocated to the plasma membrane in a spotty distribution (arrows). (C) The addition of CpG DNA leads to MyD88 recruitment to vesicles surrounding the nucleus (results from one experiment out of four are shown; magnification, ×750).

DISCUSSION

The human skin is well protected against pathogen invasion by various mechanisms that represent the so-called first line of defense. However, this protection works only in the intact skin, and once the barrier function is compromised, additional defense reactions are needed. Since the infliction of wounds and, thus, barrier breakdown are frequent events, the onsite presence of components of the innate immune system should help to rapidly induce protective reactions against invading pathogens. An important feature of innate immunity is the pathogen-associated molecular pattern recognition via TLRs. Indeed, it has been shown previously that both keratinocytes and dermal endothelial cells can express TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR5, and TLR10 in epidermal cells (16) and TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 in endothelial cells (7, 18). Since wounds usually are associated with endothelial damage and since endothelial cells are important gatekeepers in regulating leukocyte infiltration and, thus, local immune responses, here we studied TLR expression and function in human dermal endothelial cells. We also examined the impact of a proinflammatory environment, again because such a reaction is known to occur during and to be crucial for the healing process. To demonstrate the expression of the TLRs on the protein level and therefore the functionality of the receptors, we examined the relatively early event of IL-8 secretion, a well-known endothelial function serving leukocyte recruitment, and the comparatively late event of iNOS expression, a hallmark of inflammation and an important reaction in the wound-healing process (12, 20, 25).

Our results can be summarized as three major findings. (i) At the mRNA level, skin-derived endothelial cells express 7 or 8 of the 10 TLR genes. (ii) A proinflammatory environment will induce a nonuniformly altered gene usage, leading to the expression of all 10 TLRs in these cells. (iii) By measuring IL-8 release, iNOS gene expression, or MyD88 recruitment, we can demonstrate the functional activity of the receptors, although the responses are different with different ligands (Tables 4 and 5).

TABLE 4.

Overview of TLR expression

| Cell type | Expression ofa:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | TLR2 | TLR3 | TLR4 | TLR5 | TLR6 | TLR7 | TLR8 | TLR9 | TLR10 | |

| Resting HMEC-1 | ++ | + | + | +++ | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| Activated HMEC-1 | → | ↑ | ↑ | → | → | ↓ | ↑ | → | → | → |

| Resting HDMEC | + | +++ | + | +++ | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| Activated HDMEC | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↓ | → | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↑ |

+, weak TLR expression (100 ng of cDNA needed for a detection signal); ++, medium-strength TLR expression (20 ng of cDNA needed for medium-sized CT values); +++, strong TLR expression (4 ng of cDNA needed for medium-sized CT values); −, no TLR expression within 40 cycles; ↑, increase of TLR expression; ↓, decrease of TLR expression; →, no significant changes in TLR expression.

TABLE 5.

Overview of TLR function

| TLR function and cell type | Change in function after challenge with specific liganda

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR2 (Pam3Cys) | TLR2 (LTA) | TLR3 [poly(I:C)] | TLR4 (LPS) | TLR5 (flagellin) | TLR7 (imiquimod) | TLR9 (CpG DNA) | |

| IL-8 release | |||||||

| Resting HMEC-1 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | → | → |

| Activated HMEC-1 | ↑ | → | ↑ | ↑ | → | ↓ | → |

| Resting HDMEC | → | ↑ | ↑ | → | → | ↓ | |

| Activated HDMEC | → | (↑) | (↑) | → | → | → | |

| iNOS expression | |||||||

| Resting HMEC-1 | → | → | ↑ | → | ↓ | → | ↓ |

| Activated HMEC-1 | ↑ | → | → | → | → | → | → |

| Resting HDMEC | [→] | → | ↑ | ↑ | [→] | [→] | |

| Activated HDMEC | ↑ | → | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |

The ligand used is indicated in parentheses. ↑, increase of IL-8 release or iNOS expression; ↓, decrease of IL-8 release or iNOS expression; →, no significant changes in IL-8 release or iNOS expression; (↑), increase only after challenge with the cytokine doublet; [→], conventional two-step RT-PCR.

In resting, nonactivated cells, the TLR expression patterns of the cell line and the primary nonimmortalized cells are identical, with the exception of that for TLR10, which is not expressed in the latter cells. This difference likely is not due to donor-specific variations, as we used primary cells from three different donors.

Our data demonstrating that TLR expression in resting endothelial cells agree with the previously observed expression of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 (7, 18) and further extend the list of endothelial TLR uses.

Upon mimicking an inflammatory environment by culturing the cells in the presence of proinflammatory cytokines, we were surprised to find that all 10 receptors were expressed. To our knowledge, this is the first observation of a single human cell type expressing all of the TLR genes. The cytokine-induced modulation of TLR expression is nonuniform, and we found three different types of responses: (i) increased or de novo expression, (ii) expressional decreases, or (iii) a constitutive type of expression. Here, the differences between immortalized and primary cells become apparent. In general, cytokine-induced responses are more prominent in primary cells, whereas effects in the cell line appear blunted, which may explain why increases in TLR1 and de novo TLR8 expression are significant in primary cells only. The most prominent difference is with TLR genes from the second group, in which only TLR6 shows significant downregulation in the cell line, whereas in primary cells this is seen with TLR5 only.

With regard to the functional studies, the results can again be grouped into three different classes: (i) activity found in resting and activated conditions, (ii) activity seen in the presence of cytokines only, and (iii) no activity noted under resting conditions despite expression. The overall responses differ between the cell line and the primary cells, again indicating that signaling is altered during the immortalization process. However, screening for responses under any of the conditions reveals that all receptors tested are indeed functionally active in skin-derived endothelial cells. Some TLR responses are absent in the resting state but are significant under proinflammatory conditions, indicating the need for combined signals for effector function. Some ligands increase IL-8 production with no iNOS induction found, such as that with Pam3Cys, or vice versa, such as with flagellin in primary cells. In initial experiments, we also had included peptidoglycan, as this was thought to represent a ligand for TLR2, but recently it has been recognized as an NOD1/2 ligand (17, 22). Interestingly, this receptor also appears to be functional in activated endothelial cells, leading to highly increased iNOS expression in the presence of proinflammatory cytokines (by a factor of 4.5; data not shown).

Of special interest is the finding that the response also can result in the downregulation of basal IL-8 production or iNOS expression below the constitutive levels, as is seen for flagellin and imiquimod but is most significant for CpG DNA. Interestingly, a similar observation has been published recently for the systemic application of CpG DNA, in which a sequence lacking the poly(G) tail was used and in which T-cell suppression was seen when CpG DNA was administered systemically, a path that initially addresses the endothelia (11). In studying the immediate signaling route via the detection of endogenous MyD88 and its subcellular redistribution following ligand addition, we indeed found the expected routing towards the plasma membrane with LPS and to intracellular vesicles after CpG DNA addition, whereas poly(I:C) challenge did not induce redistribution. This also shows that the unexpected suppressive response to CpG DNA occurs as a consequence of the well-characterized signaling pathway.

In summary, here we provide evidence that human skin endothelial cells are extremely well equipped for recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Moreover, this cell type will actively respond in a specific nonuniform manner to the different TLR ligands. Of note, the response does not always consist of an upregulation of the inflammatory response but also can represent suppression. It thus appears that skin endothelia play a major role in innate immune responses and may well represent the only cell type for which the expression of all TLR genes currently known is seen (9, 10).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Lenzen for technical assistance with cell cultures and conventional microscopy.

This work was supported in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB503 A3 to V.K.-B.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartz, H., Y. Mendoza, M. Gebker, T. Fischborn, K. Heeg, and A. Dalpke. 2004. Poly-guanosine strings improve cellular uptake and stimulatory activity of phosphodiester CpG oligonucleotides in human leukocytes. Vaccine 23:148-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourke, E., D. Bosisio, J. Golay, N. Polentarutti, and A. Mantovani. 2003. The toll-like receptor repertoire of human B lymphocytes: inducible and selective expression of TLR9 and TLR10 in normal and transformed cells. Blood 102:956-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christopherson, K. W., Jr., and R. A. Hromas. 2004. Endothelial chemokines in autoimmune disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10:145-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cristofaro, P., and S. M. Opal. 2003. The Toll-like receptors and their role in septic shock. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 7:603-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edfeldt, K., J. Swedenborg, G. K. Hansson, and Z. Q. Yan. 2002. Expression of toll-like receptors in human atherosclerotic lesions: a possible pathway for plaque activation. Circulation 105:1158-1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Equils, O., A. Shapiro, Z. Madak, C. Liu, and D. Lu. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors block Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)- and TLR4-induced NF-κB activation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3905-3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faure, E., O. Equils, P. A. Sieling, L. Thomas, F. X. Zhang, C. J. Kirschning, N. Polentarutti, M. Muzio, and M. Arditi. 2000. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates NF-κB through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) in cultured human dermal endothelial cells. Differential expression of TLR-4 and TLR-2 in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11058-11063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faure, E., L. Thomas, H. Xu, A. Medvedev, O. Equils, and M. Arditi. 2001. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide and IFN-gamma induce Toll-like receptor 2 and Toll-like receptor 4 expression in human endothelial cells: role of NF-κB activation. J. Immunol. 166:2018-2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzner, N. 2007. Ph.D. thesis. University of Duesseldorf, Germany.

- 10.Fitzner, N., and V. Kolb-Bachofen. 2006. Functional expression of toll-like receptors (TLR's) on human endothelial cells activate the inducible nitric oxide synthase. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 85:114-115. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerhard-Wingender, N. G., B. Schumak, F. Juengerkes, E. Endl, D. von Bubnoff, J. Steitz, J. Striegler, G. Moldenhauer, T. Tüting, A. Heit, K. M. Huster, O. Takikawa, S. Akira, D. H. Busch, H. Wagner, G. J. Haemmerling, P. A. Knolle, and A. Limmer. 2006. Systemic application of CpG-rich DNA suppresses adaptive T cell immunity via induction of IDO. Eur. J. Immunol. 36:12-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillitzer, R., and M. Goebeler. 2001. Chemokines in cutaneous wound healing. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69:513-521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iacobas, D. A., S. Iacobas, W. E. I. Li, G. Zoidl, R. Dermietzel, and D. C. Spray. 2005. Genes controlling multiple functional pathways are transcriptionally regulated in connexin43 null mouse heart. Physiol. Genomics 20:211-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kluger, M. S. 2004. Vascular endothelial cell adhesion and signaling during leukocyte recruitment. Adv. Dermatol. 20:163-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knolle, P. A., and A. Limmer. 2003. Control of immune responses by savenger liver endothelial cells. Swiss Med. Wkly. 133:501-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Köllisch, G., B. N. Kalali, V. Voelcker, R. Wallich, H. Behrendt, J. Ring, S. Bauer, T. Jakob, M. Mempel, and M. Ollert. 2005. Various members of the Toll-like receptor family contribute to the innate immune response of human epidermal keratinocytes. Immunology 114:531-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kufer, T. A., D. J. Banks, and D. J. Philpott. 2006. Innate immune sensing of microbes by Nod proteins. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1072:19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, J., Z. Ma, Z. L. Tang, T. Stevens, B. Pitt, and S. Li. 2004. CpG DNA-mediated immune response in pulmonary endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 287:L552-L558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozato, K., H. Tsujimura, and T. Tamura. 2002. Toll-like receptor signaling and regulation of cytokine gene expression in the immune system. BioTechniques 2002 Oct.(Suppl.):66-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwentker, A., and T. R. Billiar. 2003. Nitric oxide and wound repair. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 83:521-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stallmeyer, B., H. Kampfer, N. Kolb, J. Pfeilschifter, and S. Frank. 1999. The function of nitric oxide in wound repair: inhibition of inducible nitric oxide-synthase severely impairs wound reepithelialization. J. Investig. Dermatol. 113:1090-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strober, W., P. J. Murray, A. Kitani, and T. Watanabe. 2006. Signalling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6:9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeda, K., and S. Akira. 2005. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 17:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tobias, P., and L. K. Curtiss. 2005. Thematic review series: the immune system and atherogenesis. Paying the price for pathogen protection: toll receptors in atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 46:404-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weller, R. 2003. Nitric oxide: a key mediator in cutaneous physiology. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 28:511-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamasaki, K., H. D. J. Edington, C. McClosky, E. Tzeng, A. Lizonova, I. Kovesdi, D. L. Steed, and T. R. Billiar. 1998. Reversal of impaired wound repair in iNOS-deficient mice by topical adenoviral-mediated iNOS gene transfer. J. Clin. Investig. 101:967-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarember, K. A., and P. J. Godowski. 2002. Tissue expression of human Toll-like receptors and differential regulation of Toll-like receptor mRNAs in leukocytes in response to microbes, their products, and cytokines. J. Immunol. 168:554-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]