Abstract

Methanotrophic bacteria constitute a ubiquitous group of microorganisms playing an important role in the biogeochemical carbon cycle and in control of global warming through natural reduction of methane emission. These bacteria share the unique ability of using methane as a sole carbon and energy source and have been found in a great variety of habitats. Phylogenetically, known methanotrophs constitute a rather limited group and have so far only been affiliated with the Proteobacteria. Here, we report the isolation and initial characterization of a nonproteobacterial obligately methanotrophic bacterium. The isolate, designated Kam1, was recovered from an acidic hot spring in Kamchatka, Russia, and is more thermoacidophilic than any other known methanotroph, with optimal growth at ≈55°C and pH 3.5. Kam1 is only distantly related to all previously known methanotrophs and belongs to the Verrucomicrobia lineage of evolution. Genes for methane monooxygenases, essential for initiation of methane oxidation, could not be detected by using standard primers in PCR amplification and Southern blot analysis, suggesting the presence of a different methane oxidation enzyme. Kam1 also lacks the well developed intracellular membrane systems typical for other methanotrophs. The isolate represents a previously unrecognized biological methane sink, and, due to its unusual phylogenetic affiliation, it will shed important light on the origin, evolution, and diversity of biological methane oxidation and on the adaptation of this process to extreme habitats. Furthermore, Kam1 will add to our knowledge of the metabolic traits and biogeochemical roles of the widespread but poorly understood Verrucomicrobia phylum.

Keywords: extremophile, methanotroph

Aerobic methane-oxidizing bacteria (MOB) are widespread in natural environments such as soils, sediments, fresh and marine waters and wetlands, and anthropogenic habitats like rice paddies and landfills, where they feed on methane formed by methanogens present in anoxic zones of these environments (1, 2). Methane is first oxidized to methanol by key enzymes termed particulate or soluble methane monooxygenase in a reaction requiring molecular oxygen and subsequently oxidized to CO2 via formaldehyde and formate (2). Carbon is assimilated from formaldehyde via either the serine or the ribulose monophosphate pathway (3). Another hallmark for MOB is the presence of extensive intracellular membrane systems (ICM), in which the particulate methane monooxygenase is embedded (2, 4). Although MOB are nutritional specialists generally restricted to oxidation of one-carbon compounds like methane, methanol, and formate, a genus of facultatively methanotrophic bacteria, Methylocella, which also can use two-carbon compounds, has recently been identified (5). The members of this genus are moderate acidophiles, possessing only the soluble form of methane monooxygenase, and they lack the well developed ICM typical for all other known methanotrophs (6). In addition, a filamentous and probably facultative methanotroph, originally referred to as Crenothrix polyspora by Ferdinand Cohn in 1870, that possesses an unusual particular methane monooxygenase is described in ref. 7. A related bacterium, Clonothrix fusca Rose 1896 is described in ref. 8. Both of the latter organisms are sheathed bacteria found in fresh water and well known for blocking of wells, but they have not yet been cultivated. So far, all cultivated MOB belong to the gamma and alpha subclasses of the Proteobacteria phylum, forming 14 established genera (9). The origin and evolution of biological methane oxidation is unclear, but particulate methane monooxygenase shares an evolutionary relationship with the ammonium monooxygense present in the phylogenetically much more diverse group of nitrifying prokaryotes (10, 11). A common ancestor of these enzymes is plausible.

Most MOB are mesophilic organisms growing optimally at neutral pH. Only a few thermophilic species, with optimal growth temperatures at 55–59°C, have so far been described (12, 13). Two genera of moderately acidophilic MOB with optimum pH for growth at 5.0–5.5 have been characterized (12). The latter species were recovered from acidic peat bogs and grow in the temperature range of 4–30°C. Closely related but still uncultivated species have also been detected in 16S rRNA gene libraries of acidic soil samples from the Yellowstone National Park rainbow springs (14). The aim of the present study was to extend our knowledge about extremophilic MOB through cultivation efforts, using a sample from an acidic hot spring. The results demonstrate that the ability of microbial methane oxidation is phylogenetically more widespread than previously believed and can take place even in hot acidic habitats.

Results and Discussion

Isolation of a Thermoacidophilic MOB.

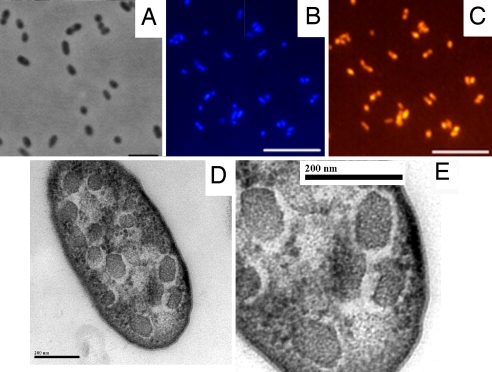

To enrich for thermoacidophilic MOB, 1 ml of a slurry sample from an acidic Kamchatkan hot spring was added to 10 ml of nitrate-free low-salt mineral medium (M3) (15) adjusted to pH 3.5 in a 120-ml serum bottle. The bottle was closed with a butyl rubber cap with an aluminum crimp seal. A mixture of methane, CO2, and air was added aseptically through a syringe to achieve ≈60%, 10%, and 30% concentration in the headspace, respectively. The only nitrogen source was N2 from the air. The bottle was incubated at 55°C with shaking at 150 rpm in the dark, and the gas mixture was replaced once per week. After 3 weeks of incubation, a weak turbidity had developed, and bacterial growth was confirmed by phase-contrast microscopy. After subculturing in fresh medium four times, only a single morphotype was observed. All subsequent cultivation was performed by using the low-salt mineral medium supplemented with KNO3 (0.1 g·liter−1). The cultures reached a density of ≈109 cells per milliliter. A methanotrophic isolate was recovered from this culture by a serial 10-fold dilution, which was repeated once. The final isolate, designated Kam1, was an oval rod with a length of 0.8–1.0 μm and a diameter of 0.45–0.65 μm (Fig. 1A). It was capable of using nitrate, ammonium and N2 as a nitrogen source. Kam1 grew from 37 to 60°C and in a pH range from 2 to 5. Only slight increases in pH (≤0.1 units) were observed. Optimal growth was at ≈55°C and pH 3.5. Cells occurred individually or in loose aggregates in the culture. No growth was observed in the absence of methane or in the presence of methane under anaerobic conditions. In the absence of methane, Kam1 grew only in the presence of low concentrations of methanol (2–36 μM) and not in the presence of ethanol, acetate, glucose, or medium supplemented with 0.25% (vol/vol) Luria-Bertani broth adjusted to pH 3.5, indicating obligate methanotrophy. No growth was observed in media routinely used for cultivation of methanotrophic bacteria, like NMS and AMS (16) or M1 (15), or in 10-fold diluted or full-strength Luria-Bertani broth at pH 3.5. No colonies appeared on M3 agar plates after 3 weeks of incubation at 55°C with CH4 and air.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs of the methanotrophic nonproteobacterial strain Kam1. (A) Phase-contrast image of Kam1 cells at 1,000× magnification. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (B and C) Fluorescent in situ hybridization images of Kam1 cells visualized with DAPI staining and the Cy3-labeled 16S rRNA gene probe Kam1_964 (5′-CTGTGCCGTTCGCCCTTGC-3′), specifically designed for the Verrucomicrobia thermoacidophilic methanotroph (VTAM) cluster, respectively. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (D) Transmission electron micrograph of a thin section of a Kam1 cell. (Scale bar, 200 nm.) (E) Magnified part of the Kam1 cell in D, highlighting the polyhedral organelles. (Scale bar, 200 nm.)

Kam1 Is Affiliated with the Verrucomicrobia Phylum.

A comparative analysis of the nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene revealed only a very distant relationship to cultivated proteobacterial methanotrophs, implying that Kam1 represents the first nonproteobacterial MOB. A high sequence identity (>98%) to a set of environmental clones from acidic hot springs in the Yellowstone National Park was, however, found (accession nos. AY882698, AY882699, AY882710, AY882819, AY882820, and AY882834). The high sequence similarity of these clones to Kam1 may indicate a common physiology and that MOB related to Kam1 could be present in the Yellowstone hot springs and possibly in other acidic and geothermal environments. These clones and Kam1 formed a tight cluster within the Verrucomicrobia phylum, which we name VTAM (Verrucomicrobia thermoacidophilic methanotroph) (Fig. 2). The Verrucomicrobia lineage was proposed as a new division in 1997 (17) and has been further divided into five monophyletic subdivisions (18, 19). The VTAM cluster is clearly separated from the other established subdivisions and thus might form a novel subdivision (Fig. 2). The closest relatives to VTAM appear to be subdivision 3 represented by the uncharacterized soil bacterium Ellin5102 from the Ellinbank pasture in Australia (20) and the environmental clone OPB35 obtained from the Yellowstone Obsidian Pool (18). Based on molecular techniques, Verrucomicrobia has been identified in a broad range of aquatic and terrestrial environments and in the gastrointestinal tract of animals and humans (18, 19, 21). In soils, they can make up 1–10% of the total bacterial 16S rRNA (22–25), suggesting that they play an important ecological role. Their metabolic activity and ecological function in most of these habitats is largely unknown. Only a few species of Verrucomicrobia have been isolated and cultivated so far (Fig. 2), and they have all been found to be mesophilic carbohydrate degraders (19). No subdivision 3 species have yet been fully characterized, but, in a recent study of soil communities, colony-forming bacteria growing on an agar plate containing carbohydrate as substrate were identified as members of this subdivision (26). Thus, methane oxidation and the thermoacidophilic nature of Kam1 indicate a larger metabolic and physiological diversity in this lineage than what has been found among the species so far cultivated.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences from Kam1 and representatives from the Verrucomicrobia phylum. Sequences were retrieved from the Ribosome Database (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu), and the Kam1 sequence was added to this alignment. The tree was constructed by using the neighbor-joining algorithm with the Kimura two-parameter correction based on 1,211 positions. Nodes supported by bootstrap values >50% after 100 resamplings of neighbor-joining, and maximum-likelihood (in brackets) analyses are indicated. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of Methylococcus capsulatus was used as an outgroup. Subdivisions are indicated by encircled numbers. The scale bar represents 0.1 nucleotide changes per position.

Trials to amplify the functional genes pmoA, mmoX, and mxaF, encoding the particulate methane monooxygenase, the soluble methane monooxygenase, and the methanol dehydrogenase, respectively, all being used as diagnostic markers and representing key methane uptake enzymes for known methano trophs, were negative (results not shown). Southern blot analyses, using radioactively labeled pmoA and mmoX probes and trials to amplify the genes for the related ammonium mono oxygenase enzyme were also negative (results not shown). This suggests the presence of methane oxidation enzymes that differ from the methane monooxygenases identified in other MOB.

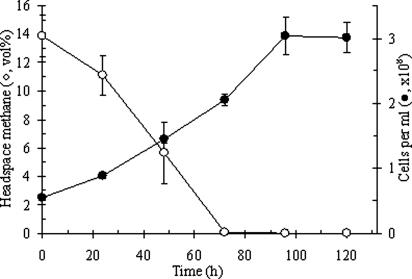

Methane Consumption and Growth.

Methane consumption was measured to verify the methane oxidation capability of Kam1. Gas chromatographic analysis combined with total cell counts showed that bacterial cell numbers increased in parallel with methane consumption, demonstrating a methanotrophic metabolism with conversion of the gas into biomass (Fig. 3). During the first 72 h, methane levels dropped from 14% (vol/vol) to below the detection limit (≈0.1%) and in the same period cell numbers raised from 5.4 × 107 to 2.1 × 108 cells per milliliter, which equals a net increase of 4.7 × 109 cells. Assuming a single cell dry mass of 1.5 × 10−13 g (27) this corresponds to a de novo biomass of ≈0.7 mg per serum bottle with 30 ml of medium. From the 2.5 mg of methane consumed, this yields a carbon incorporation efficiency of 18%, which, in addition to a reasonable methane to biomass ratio, argues against a possible contamination by a conventional MOB. The generation time was estimated to 38 h. These results are comparable to data from other pure-cultures of acidophilic methanotrophs (6) and support our conclusions that Kam1 is a bona fide MOB.

Fig. 3.

Growth and corresponding methane consumption of Kam1. Averages ± standard error are shown for triplicate 60-ml serum bottles shaken at 55°C. The pH was 3.5. No decrease in headspace methane was observed from three parallel bottles with only medium (data not shown). Black circles indicate cell numbers; open circles indicate the methane level.

Acetylene is a known inhibitor of methane monooxygenase (28). In an experiment to test the effect of acetylene on Kam1, we found that addition of 4% (vol/vol) acetylene in the headspace efficiently blocked methane oxidation and further growth of Kam1 [supporting information (SI) Fig. 4]. This effect is comparable with that observed for other methanotrophs (29) and suggests the presence of a functionally related methane oxidizing enzyme in Kam1. The naphthalene assay, which reveals the presence of the soluble form of MMO (2), was, however, negative.

Microscopic Observations.

To verify the purity of the Kam1 culture, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed with a variety of 16S rRNA-binding probes. All of the DAPI-stained cells were positive with the 16S rRNA probe Kam1_964 (Fig. 1 B and C), which was specifically designed for the members of the VTAM cluster. Hybridization with the general bacterial probe Eub338 (30) was negative, but the Verrucomicrobia-including version of this probe (Eub338III) (31) gave a positive signal (results not shown). In addition, none of the DAPI-counted cells were found to bind the MOB-specific probes Mγ84 and Mα450, targeting most type I and type II MOB, respectively (32). The purity of the Kam1 culture is also supported by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis, which yielded a single band with a nucleotide sequence identical to a fragment of the Kam1 16S rRNA gene (SI Fig. 5). These results demonstrate that the culture is pure and that no proteobacterial MOB are present.

ICM were absent in Kam1, as judged by transmission electron microscopy. However, the Kam1 cells were filled with polyhedral organelles resembling carboxysomes (Fig. 1 D and E) of cyanobacteria and chemoautotrophs. Carboxysomes contain ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (33), known to be key CO2 fixation enzymes in most autotrophs. The possibility that Kam1 assimilates CO2, using the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle, is plausible; however, as discussed in ref. 34, this would be energetically unfavorable compared with the mechanism in other methanotrophs. Polyhedral organelles are also found in some heterotrophs like Salmonella enterica during anaerobic growth on propanediol (35, 36). The function of these organelles in heterotrophs is not known, but it has been suggested that the assembly of enzymes in polyhedral organelles optimizes the metabolic processes through a metabolic channeling mechanism (37). Thus, it is intriguing to speculate that the polyhedral organelles in Kam1 may substitute for ICM and represent a novel subcellular compartment for methane oxidation.

Conclusion.

We have isolated a thermoacidophilic methanotroph belonging to the Verrucomicrobia phylum. This is, to our knowledge, the first such report of a methanotrophic organism outside the proteobacterial lineage. Its phylogenetic position, apparent lack of classical methane oxidation genes and ICM, and the presence of polyhedral organelles imply that this isolate may possess a novel type of methane oxidation system. Based on the preliminary characterization of Kam1, we propose the tentative name Methyloacida kamchatkensis, describing the methanotrophic and acidophilic properties of the isolate and the place from where it was isolated. Further biochemical and genomic studies of Kam1 are expected to provide insight into the evolution and adaptation of the methane oxidation pathways and mechanisms to extreme habitats.

Materials and Methods

Sampling and Cultivation.

The sample was harvested in August 2005 from a shallow permanent outflow of an unnamed 72°C acidic hot spring in the Eastern field of the Uzon Caldera, Kamchatka, Russia. The sampling site was chosen ≈3 m from the original spring at a location with pH 3 and a temperature of 52°C. The sample consisted of fine-granulated loose clay in mixture with the spring water flowing above the chosen site. The concentration of dissolved methane in this spring water was not measured, but, in other hot springs in this area, the concentrations of dissolved methane have been estimated to be in the 200–1,700 ppm range (N. Pimenov, personal communication). After harvesting, the sample was stored at 6°C in the dark for 1 week before cultivation. The enrichment and isolation of Kam1 was performed at 55°C, using the nitrate-free mineral liquid medium M3, a low-salt medium previously used for enrichment of acidophilic MOB (15). Phosphate was added after autoclaving and cooling to 40°C. Before use, the medium was adjusted to pH 3.5, using 1 M HCl. Growth was monitored by phase contrast microscopy, using a Nikon, Eclipse E400 microscope. Growth on alternative carbon sources was assessed with M3 medium at pH 3.5 supplemented with KNO3 (0.1 g·l−1) and one of the following substrates: glucose (10 mM), acetate (18 mM), pyruvate (10 mM), ethanol (17 mM), methanol (0.002–0.2 mM), or 0.25% (wt/vol) Luria-Bertani broth.

Methane Consumption Measurements.

Triplicate 60-ml serum bottles each containing 30 ml of medium were used to assess the methane uptake and growth as modified from a previous protocol (38). Actively growing Kam1 cells were used for inoculation. After capping the flasks with butyl rubber stoppers, a syringe was used to remove 3 ml of air followed by reinjection into the headspace of an equal volume of methane (99.95% pure) through a 0.2-μm filter. Three parallel bottles containing only medium served as controls. The bottles were left on a rotating shaker (150 rpm) at 55°C for 1 h before the first sample was withdrawn. Headspace samples (0.1 ml) were withdrawn with a syringe equipped with a luer locker. During sampling, the bottles were kept in a water bath to maintain the temperature. CH4 was analyzed in a Hewlet Packard 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with a 1.83-m Hayesep R column (80/100 mesh) and a thermal conductivity detector (150°C). The oven temperature was 35°C, and the flow rate of the carrier gas (He) was 59 ml·min−1. Growth of Kam1 cells was monitored by cell counts in a Thoma Assistant counting chamber (n = 5).

FISH and Electron Microscopy.

FISH was performed on cells in near logarithmic growth fixed in 4% paraformaldenhyde (in PBS, pH 7.2) for 1–3 h in the fridge, washed three times in the PBS, and resuspended for storage at 4°C (in 0.5× PBS in 50% ethanol). Fixed cells were air-dried on SuperFrostPlus slides (Menzel-Gläser), dehydrated in 70% ethanol, and soaked in HCl (0.2 M) and Tris-buffer (20 mM) at pH 8.0 for 10–12 min each. Permeabilisation was performed with proteinase K (0.5 μg·ml−1), before being washed in the buffer and dried. Wells were made on the slide using a wax pen, and the probes were added to a final concentration of 3.33 ng·μl−1 in hybridization buffer [0.9 M NaCl, 0.02 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 0.01% SDS, and 20% vol/vol formamide]. Hybridization was performed in a 50-ml polypropylene tube at 46°C for 3 h and followed by a rinse in prewarmed wash buffer [0.21 M NaCl, 0.02 M Tris·HCl, 0.005 M EDTA (pH 8.0), and 0.01% SDS] at 48°C for 15 min. After a dip in water (48°C) and air drying, the cells were stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1.0 μg·ml−1), washed in water, covered with 96% ethanol, dried, and mounted in VectaShield (Vector Laboratories) under a coverslip. The slides were examined in an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan) equipped with a UV lamp and a digital camera (Nikon D1). Probes were 5′ end-labeled with indocarbocyanine fluorochrome Cy3 (ThermoElectron). Before transmission electron microscopy the cells where fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 30 min followed by three washes in 0.25% NaCl solution for 10 min each and a final fixation in 1% OsO4 for 60 min. The cells where then washed and dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol before being embedded in 1:1 propylenoksyd/agar 100 resin. Thin sections (60 nm) of the sample were stained with uranyl and Reynolds lead solution and viewed in a Jeol JEM-1230 microscope at 60 kV.

Phylogenetic Analysis.

Genomic DNA from strain Kam1, extracted with a GenElute bacterial genomic DNA kit (Sigma), was used as a template for PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes with the universal eubacterial primers 27f and 1492r (39), using a Peltier thermal cycler (PTC-100; MJ Research). The PCR products were purified and sequenced by using the Bigdye kit for automated DNA sequencers (ABI 3700 PE; Applied Biosystems). Phylogenetic relationships were analyzed by evolutionary distances and maximum-likelihood methods (PHYLIP software, Version 3.6; http://evolution.gs.washington.edu/phylip.html) calculated with the Kimura two-parameter distance correction, using 1,211 aligned bases.

PCR Amplification and Southern Blot Analysis of Functional Genes.

Five sets of PCR primers were used in attempts to amplify Kam1 genes encoding particulate methane monooxygenase (pmoA), soluble methane monooxygenase (mmoX), methanol dehydrogenase (mxaF), and ammonium monooxygenase (amoA) (SI Table 1). The reactions were run in a PTC-100 thermal cycler (MJ research). The PCR program included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 29 cycles with a denaturing step of 1 min at 94°C, an annealing step of 1 min at 54–55°C, and an elongation step of 1 min at 72°C. The final elongation was for 7 min at 72°C. M. capsulatus DNA (for pmoA, mmoX, and mxaF) and soil DNA (for the Crenarchaeota-specific amoA primer set) were applied as positive controls. Water was used as negative control. All of the positive controls yielded a PCR product of correct size.

The Southern blot analysis was carried out by using EcoRI and HindIII digests of genomic DNA from Kam1 and EcoRI and SmaI digests of M. capsulatus DNA separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and blotted onto Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham Biosciences). The probes used for hybridization were obtained by PCR using the pmoA and mmoX primer sets (SI Table 1) and genomic DNA from M. capsulatus as template. The pmoA and mmoX probes covered ≈500 and 1,400 bp of the genes, respectively, and were radioactively labeled with [α-32P]dCTP, using the Ready-To-Go DNA-labeled beads (dCTP) kit (Amersham Biosciences). Hybridization was carried out at 60°C overnight in 0.5 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.2), 3% SDS, and 1 mM EDTA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Drs. Christa Schleper, Elizaveta Bonch-Osmolovskaya, Juergen Wiegel, and Frank T. Robb and the National Science Foundation-funded Kamchatkan Microbiological Observatory (which is funded by U.S. National Science Foundation Grant 0238407) for the opportunity to attend the 2005 workshop Biodiversity, Molecular Biology, and Biogeochemistry of Thermophiles (L.J.R.). This work was supported by Norwegian Research Council Grant 157346 and Norwegian Academy of Science and Statoil program Grant 6146. The imaging service was provided by the national technology platform, Molecular Imaging Centre, supported by the functional genomics program of the Norwegian Research Council.

Note Added in Proof.

After the approval of this manuscript, two similar strains were described by Dunfield et al. (40) and Pol et al. (41).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of strain Kam1 has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. EF127896).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0704162105/DC1.

References

- 1.Conrad R. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:609–640. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.609-640.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson RS, Hanson TE. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:439–471. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.439-471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony C. The Biochemistry of Methylotrophs. London: Academic; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieberman RL, Rosenzweig AC. Nature. 2005;434:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature03311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dedysh SN, Knief C, Dunfield PF. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4665–4670. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4665-4670.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dedysh SN, Liesack W, Khmelenina VN, Suzina NE, Trotsenko YA, Semrau JD, Bares AM, Panikov NS, Tiedje JM. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:955–969. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-3-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoecker K, Bendinger B, Schoning B, Nielsen PH, Nielsen JL, Baranyi C, Toenshoff ER, Daims H, Wagner M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2363–2367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506361103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vigliotta G, Nutricati E, Carata E, Tredici SM, De Stefano M, Pontieri P, Massardo DR, Prati MV, De Bellis L, Alifano P. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:3556–3565. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02678-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahalkar M, Bussmann I, Schink B. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:1073–1080. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes AJ, Costello A, Lidstrom ME, Murrell JC. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;132:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00311-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes AJ, Roslev P, McDonald IR, Iversen N, Henriksen K, Murrell JC. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3312–3318. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3312-3318.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trotsenko YA, Khmelenina VN. Arch Microbiol. 2002;177:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00203-001-0368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsubota J, Eshinimaev BT, Khmelenina VN, Trotsenko YA. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1877–1884. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamamura N, Olson SH, Ward DM, Inskeep WP. Appl Env Microbiol. 2005;71:5943–5950. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5943-5950.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dedysh SN, Panikov NS, Tiedje JM. Appl Env Microbiol. 1998;64:922–929. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.922-929.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whittenbury R, Phillips KC, Wilkinson J. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;61:205–218. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-2-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedlund BP, Gosink JJ, Staley JT. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1997;72:29–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1000348616863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hugenholtz P, Goebel BM, Pace NR. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4765–4774. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4765-4774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sangwan P, Chen XL, Hugenholtz P, Janssen PH. Appl Env Microbiol. 2004;70:5875–5881. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5875-5881.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joseph SJ, Hugenholtz P, Sangwan P, Osborne CA, Janssen PH. Appl Env Microiol. 2003;69:7210–7215. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7210-7215.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner M, Horn M. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buckley DH, Schmidt TM. Env Microbiol. 2003;5:441–452. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buckley DH, Schmidt TM. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2001;35:105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felske A, Akkermans AD, De Vos WM. Appl Env Microbiol. 1998;64:4581–4587. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4581-4587.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felske A, Wolterink A, Van Lis R, De Vos WM, Akkermans AD. Appl Env Microbiol. 2000;66:3998–4003. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.9.3998-4003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sangwan P, Kovac S, Davis KER, Sait M, Janssen PH. Appl Env Microbiol. 2005;71:8402–8410. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8402-8410.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roslev P, Iversen N, Henriksen K. Appl Env Microbiol. 1997;63:874–880. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.874-880.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prior SD, Dalton H. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;29:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bedard C, Knowles R. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:68–84. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.68-84.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amann RI, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH. Microbiol Revs. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daims H, Bruhl A, Amann R, Schleifer KH, Wagner M. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1999;22:434–444. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eller G, Stubner S, Frenzel P. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;198:91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cannon GC, Bradburne CE, Aldrich HC, Baker SH, Heinhorst S, Shively JM. Appl Env Microbiol. 2001;67:5351–5361. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5351-5361.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strøm T, Ferenci T, Quayle JR. Bioch J. 1974;144:465–476. doi: 10.1042/bj1440465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bobik TA, Havemann GD, Busch RJ, Williams DS, Aldrich HC. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5967–5975. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5967-5975.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kofoid E, Rappleye C, Stojiljkovic I, Roth J. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5317–5329. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5317-5329.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bobik TA. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;70:517–525. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen S, Prieme A, Bakken L. App Env Microbiol. 1998;64:1143–1146. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1143-1146.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lane DJ. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunfield PF, Yuryev A, Senin P, Smirnova AV, Stott MB, Hou S, Ly B, Saw JH, Zhou Z, Ren Y, et al. Nature. 2007;450:879–882. doi: 10.1038/nature06411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pol A, Heijmans K, Harhangi HR, Tedesco D, Jetten MS, Op den Camp HJ. Nature. 2007;450:874–878. doi: 10.1038/nature06222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.