Abstract

Episodic memories allow us to remember not only that we have seen an item before but also where and when we have seen it (context). Sometimes, we can confidently report that we have seen something (familiarity) but cannot recollect where or when it was seen. Thus, the two components of episodic recall, familiarity and recollection, can be behaviorally dissociated. It is not clear, however, whether these two components of memory are represented separately by distinct brain structures or different populations of neurons in a single anatomical structure. Here, we report that the spiking activity of single neurons in the human hippocampus and amygdala [the medial temporal lobe (MTL)] contain information about both components of memory. We analyzed a class of neurons that changed its firing rate to the second presentation of a previously novel stimulus. We found that the neuronal activity evoked by the presentation of a familiar stimulus (during retrieval) distinguishes stimuli that will be successfully recollected from stimuli that will not be recollected. Importantly, the ability to predict whether a stimulus is familiar is not influenced by whether the stimulus will later be recollected. We thus conclude that human MTL neurons contain information about both components of memory. These data support a continuous strength of memory model of MTL function: the stronger the neuronal response, the better the memory.

Keywords: hippocampus, single-unit, episodic memory, recollection, recognition

Episodic memories allow us to remember not only whether we have seen something before but also where and when (contextual information). One of the defining features of an episodic memory is the combination of multiple pieces of experienced information into one unit of memory. An episodic memory is, by definition, an event that happened only once. Thus, the encoding of an episodic memory must be successful after a single experience. When we recall such a memory, we are vividly aware that we have personally experienced the facts (where, when) associated with it. This contrasts with pure familiarity memory, which includes recognition, but not the “where” and “when” features. The medial temporal lobe (MTL), which receives input from a wide variety of sensory and prefrontal areas, plays a crucial role in the acquisition and retrieval of recent episodic memories. Neurons in the primate MTL respond to a wide variety of stimulus attributes, such as object identity (1, 2) and spatial location (3). Similarly, the MTL is involved in the detection of novel stimuli (4, 5). Some neurons carry information about the familiarity or novelty of a stimulus (6, 7) and are capable of changing that response after a single learning trial (6). The MTL, and in particular the hippocampus, are thus ideally suited to combine information about the familiarity/novelty of a stimulus with other attributes, such as the place and time of occurrence.

The successful recall of an experience depends on neuronal activity during acquisition, maintenance, and retrieval. The MTL plays a role in all three components. Here, we focus on the neuronal activity of individual neurons during retrieval. The MTL is crucially involved in the retrieval of previously acquired memories: brief local electrical stimulation of the human MTL during retrieval leads to severe retrieval deficits (8). Two fundamental components of an episodic memory are whether the stimulus is familiar and, if it is, whether information is available about when and where the stimulus was previously experienced (e.g., recollection). How these components interact, however, is not clear. A key question is whether there are distinct anatomical structures involved in these two processes (familiarity vs. recollection).

Some have argued that the hippocampus is exclusively involved in the process of recollection but not familiarity (9, 10). Evidence from behavioral studies with lesion patients, however, seems to argue against this view (11–13). Rather than removing the capability of recollection while leaving recognition (familiarity) intact, hippocampal lesions cause a decrease in overall memory capacity rather than the loss of a specific function. Lesion studies, however, do not allow one to distinguish between acquisition vs. retrieval deficits.

Recollection of episodic memories is difficult to study in animals (but see ref. 14) but can easily be assessed in humans. Recordings from humans offer the unique opportunity to observe neurons engaged in the acquisition and retrieval of episodic memories. We recorded from single neurons in the human hippocampus and amygdala during retrieval of episodic memories. We used a memory task that enabled us to determine whether a stimulus was only recognized as familiar or whether an attribute associated with the stimulus (the spatial location) could also be recollected. We hypothesized that the neuronal activity evoked by the presentation of a familiar stimulus would differ depending on whether the location of the stimulus would later be recollected successfully. We found that the neuronal activity contains information about both the familiarity and the recollective component of the memory.

Results

Behavior.

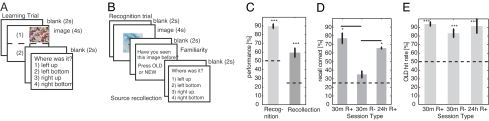

During learning, subjects [see supporting information (SI) Table 1 for neuropsychological data] were shown 12 different pictures presented for 4 s each (Fig. 1A). Subjects were asked to remember the pictures they had seen (recognition) and where they had seen them (position on the screen). After a delay of 30 min or 24 h, subjects were shown a sequence of 12 previously seen (“old”) and 12 entirely different (“new”) pictures (Fig. 1B). Subjects indicated whether they had seen the picture before and where the stimulus was when they saw it the first time. We refer to the true status of the stimulus as old or new and the subject's response as “familiar” or “novel.” With the exception of error trials the two terms are equivalent. Subjects remembered 90 ± 3% of all old stimuli and for 60 ± 5% of those they remembered the correct location (Fig. 1C). Some subjects were not able to recollect the spatial location of the stimuli whereas others remembered the location of almost all stimuli. For each 30-min retrieval session, we determined whether the patient exhibited, on average, above-chance (R+) or at-chance (R−) spatial recollection and then calculated the behavioral performance separately (Fig. 1 D and E). Patients with good same-day spatial recollection performance (30-min R+) remembered the spatial location of on average 77 ± 6% (significantly different from 25% chance, P < 0.05, z test) of stimuli they correctly recognized as familiar whereas at-chance patients (30-min R−) recollected only 35 ± 4% of stimuli (approaching but not achieving statistical significance, P = 0.07). Thus, there were two behavioral groups for the 30-min delay: one with good and one with poor recollection performance.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup and behavioral performance. (A and B) The experiment consists of learning (A) and retrieval (B) blocks. (C) Patients exhibited memory for both the pictures they had seen (recognition) and where they had seen them (recollection). n = 17 sessions. (D) Two different time delays were used: 30 min and 24 h. Thirty-minute delay sessions were separated into two groups according to whether recollection performance was above-chance or not. (E) For all groups, patients had good recognition performance for old stimuli, whether they were able to successfully recollect the source. n = 7, 5, and 4 sessions, respectively. Errors are ±SEM. Horizontal lines indicate chance performance. R+, above-chance recollection; R−, at-chance recollection.

We also tested a subset of the subjects that had good recollection performance on the first day with an additional test 24 h later (four subjects). Subjects saw a new set of pictures and were asked to remember them overnight. Overnight memory for the spatial location was good (66 ± 1%, P < 0.05). All three behavioral groups (30-min R+, 30-min R−, 24-h R+) had good recognition performance (Fig. 1E) that did not differ significantly between groups (ANOVA, P = 0.24). The false-positive (FP) rate was on average 7 ± 3% and did not differ significantly between groups (ANOVA, P = 0.37).

Single-Unit Responses During Retrieval.

We recorded the activity of 412 well separated units in the hippocampus (n = 218) and amygdala (n = 194) in 17 recording sessions from eight patients [24.24 ± 11.51 neurons ± SD per session]. The mean firing rate of all neurons was 1.45 ± 0.10 Hz and was not significantly different between the amygdala and the hippocampus (SI Fig. 5A). For each neuron, we determined whether its firing differed significantly in response to correctly recognized old vs. new stimuli. Note that “old” indicates that the subject has seen the image previously during the learning part of the experiment. Thus, the difference between a novel and old stimulus is only a single stimulus presentation (single-trial learning). We found a subset of neurons (114, 6.7 ± 4.7 per session; see SI Table 2) that contained significant information about whether the stimulus was old or new. Because error trials were excluded for this analysis, the physical status (old or new) is equal to the perceived status (familiar or novel) of the stimulus. Neurons were classified as either familiarity (n = 37) or novelty detectors (n = 77) depending on the stimulus category for which their firing rate was higher (see Methods). The analysis presented here is based on this subset of neurons. The mean firing rate of all significant neurons (1.6 ± 0.2 Hz, n = 114) did not differ significantly from the neurons not classified as such (1.4 ± 0.1 Hz, n = 298). Similarly, the mean firing rate of neurons that increase firing in response to novel stimuli was not different from neurons that increase firing in response to old stimuli (SI Fig. 5 C and D).

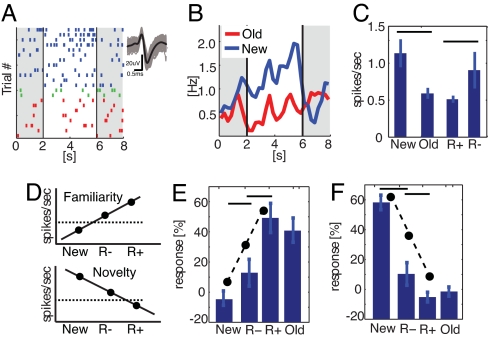

The response of a neuron that increased firing for new stimuli is illustrated in Fig. 2 A–C. This neuron fired, on average, 1.1 ± 0.2 spikes per second when a new stimulus was presented and only 0.6 ± 0.1 spike per second when a correctly recognized old stimulus was presented (Fig. 2C). Of the 10 old stimuli (2 were wrongly classified as novel and are excluded), 8 were later recollected, whereas 2 were not. For the 8 later recollected items (R+), the neuron fired significantly fewer spikes than for the not recollected items (0.5 ± 0.1 vs. 0.9 ± 0.3, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2C). Thus, this neuron fired fewer spikes for items that were both recollected and recognized than for items that were not recollected. We found a similar but opposite pattern for neurons that increase their firing in response to old stimuli (see below). We thus hypothesized that these neurons represent a continuous gradient of memory strength: the stronger the memory, the more spikes that are fired by familiarity-detecting neurons (Fig. 2D). Similarly, we hypothesized that the opposite relation would hold for novelty neurons: the fewer spikes, the stronger the memory.

Fig. 2.

Single-cell response. (A–C) Firing of a unit in the right hippocampus that increases its firing in response to new stimuli that were correctly recognized (novelty detector). (A) Raster of all trials during retrieval and the waveforms associated with every spike. Trials: new (blue), old and recollected (red, R+), and old and not recollected (green, R−). (B) Poststimulus time histogram. (C) Mean number of spikes after stimulus onset. Firing was significantly larger in response to new stimuli and the neuron fired more spikes in response to stimuli that were later not recollected compared with stimuli that were recollected. (D) The hypothesis: The less that novelty neurons fire, the more likely it is that a stimulus will be recollected. The more that familiarity-detecting neurons fire, the more likely it is that a stimulus will be recollected. The dashed line indicates the baseline. (E and F) Normalized firing rate (baseline = 0) of all novelty (E) and familiarity-detecting (F) neurons during above-chance sessions (30-min R+). Novelty neurons fired more in response to not recollected items (R−) whereas familiarity neurons fired more in response to recollected items (R+). Errors are ± SEM. nr of trials, from left to right: 388, 79, 259, and 338 (E) and 132, 31, 96, and 127 (F).

We analyzed three groups of sessions separately: same-day with good recollection performance (30-min R+), same-day with at-chance recollection performance (30-min R−), and overnight with above-chance recollection (24-h R+). Sessions were assigned to the 30-min R+ or 30-min R− groups based on behavioral performance. We hypothesized that if the neuronal firing evoked by the presentation of an old stimulus is purely determined by its familiarity, the neuronal firing should not differ between stimuli that were only recognized and stimuli that were also recollected. However, if there is a recollective component, then a difference in firing rate should only be observed for recording sessions in which the subject exhibited good recollection performance.

First, we examined the novelty (Fig. 2E) and familiarity neurons (Fig. 2F) in the 30-min R+ group. The prestimulus baseline was, on average, 1.7 ± 0.4 Hz (range 0.06–9.5) and 2.6 ± 1.0 Hz (range 0.2–12.9) for novelty and familiarity neurons, respectively, and was not significantly different. Units responding to novel stimuli increased their firing rate on average by 58 ± 5% relative to baseline. Similarly, units responding to old stimuli increased their firing by 41 ± 8% during the second stimulus presentation. We divided the trials for repeated stimuli into two classes: stimuli that were later recollected (R+) and not recollected (R−). A within-neuron repeated measures ANOVA (factor trial-type: new, R− or R+) revealed a significant effect of trial type for both novelty (P < 1 × 10−12) and familiarity units (P < 1 × 10−6). This test assumes that neurons respond independently from each other. For both types of units, we performed two planned comparisons: (i) new vs. R− and (ii) R− vs. R+. For novelty neurons, the hypothesis was that the amount of neural activity would have the following relation: new > R− and R− > R+. For familiarity, the hypothesis was the opposite: new < R− and R− < R+ (see Fig. 2D). For novelty and familiarity neurons, each prediction proved to be significant (one-tailed t test. Novelty: new vs. R− t = 4.3, P < 1 × 10−4 and R− vs. R+ t = 2.2, P = 0.01. Familiarity: new vs. R− t = −1.7, P = 0.05 and R− vs. R+ t = −2.0, P = 0.02). Thus, both novelty- and familiarity-detecting neurons signaled that a stimulus is repeated even in the absence of recollection (new vs. R−) and whether a stimulus was recollected or not (R− vs. R+).

The same analysis applied to the remaining groups (30-min R− and 24-h R+) revealed a significant main effect of trial type for novelty (P < 1 × 10−4 and P < 1 × 10−5, respectively) and familiarity neurons (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively). However, only the new vs. R− planned comparison was significant (novelty: P < 0.001 and P < 0.001; familiarity: P < 0.001 and P < 0.001), whereas the R− vs. R+ comparison was not significant for either group (novelty: P = 0.6 and P = 0.7; familiarity: P = 0.68 and 0.49). Thus, the activity of these units was different for new vs. old stimuli, but the response to old items was indistinguishable for recollected vs. not recollected stimuli.

Quantification of the Single-Trial Responses.

Both groups of neurons distinguished recollected from not recollected stimuli, but the difference was of opposite sign. In the novelty case, neurons fire less strongly for recollected items (Fig. 2E), whereas, in the familiarity case, neurons fire more strongly (Fig. 2F). We thus hypothesized that both neuron classes represent a continuous gradient of memory strength. In one case, firing increases with the strength of memory (familiarity detectors), whereas, in the other case, firing decreases with the strength of memory (novelty detectors). Thus, a strong memory (R+) is signaled both by strong firing of familiarity units and weak firing of novelty neurons. Weak memory (R−) is signaled by moderate firing of familiarity and novelty neurons. No memory (a new item) is signaled by strong firing of novelty detectors and weak firing of familiarity detectors. Another feature of the response is that it is often bimodal (see also SI Fig. 6). For example, familiarity neurons do not only increase their firing for old items but also decrease firing to new items (Fig. 2F). This pattern can also be observed in the firing pattern shown in Fig. 2A: Immediately after stimulus onset, this neuron reduces its firing if the stimulus is old.

We developed a response index R(i) that takes into account the opposite sign of the gradient for the two neuron types, the bimodal response and different baseline firing rates. This index makes use of the entire dynamic range of each neuron's response. R(i) is equal to the number of spikes fired during a particular trial i, minus the mean number of spikes fired to all new stimuli divided by the baseline (Eq. 1). For example, if a neuron doubles its firing rate for an old stimulus and remains at baseline for a novel stimulus, the response index would equal 100%. By definition, R(i) is negative for novelty units, and, thus, we multiplied R(i) by −1 if the unit was previously classified as a novelty unit.

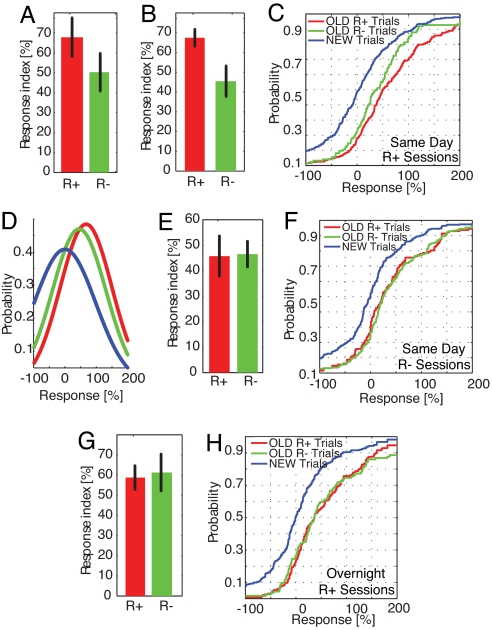

First, we describe the response of the 30-min R+ group. In terms of the response index, the average response was significantly stronger to presentation of old stimuli that were later recollected when compared with stimuli that were later not recollected. This was true for a pairwise comparison for every neuron (Fig. 3A, 68% vs. 50%, n = 45 neurons from four subjects) and for a trial-by-trial comparison (Fig. 3B, 67% vs. 45%, P < 0.01, n = number of trials). Note that the same difference exists if neurons from the hippocampus (n = 30, R+ vs. R−, P < 0.05) or the amygdala (n = 15, R+ vs. R−, P < 0.05) are considered separately (see SI Fig. 7A and SI Table 2). The difference in response (of 22%) is entirely due to recollection of the source. Replotting the data as a cumulative distribution function (cdf) shows a shift of the entire distribution because of recollection (Fig. 3C, green vs. red line; P ≤ 0.01). The cdf shows the proportion of all trials that are smaller than a given value of the response index. It illustrates the entire distribution of the data rather than just its mean. We also calculated the response index for correctly identified new items. By definition, the mean response to novel stimuli is 0, but it varies trial-by-trial (blue line). The shift in response induced by familiarity alone (blue vs. green, P ≤ 1 × 10−5) lies in between the shift induced by comparing novel stimuli with old stimuli that were successfully recollected (Fig. 3C, blue vs. red, P ≤ 1 × 10−19). The response index is thus a continuous measure of memory strength. From the point of view of this measure, novel items are distractors, and old items are targets. We fitted normal density functions to the three populations (distractors, R− and R+ targets). R+ Targets were more different from the distractors than were R− targets (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Neuronal activity distinguishes stimuli that are only recognized (R−) from stimuli that are also recollected (R+). (A–E) Same-day sessions with above-chance recollection performance (30-min R+). (A) Pairwise comparison of the mean response for all 45 neurons (paired t test). (B) Trial-by-trial comparison. The response was significantly higher for stimuli that were recalled (R+, n = 386) compared with the response to stimuli that were not recalled (R−, n = 123). n is number of trials. (C) Cumulative distribution function (cdf) of the data shown in B. The response to new stimuli is shown in blue (median is 0). The shift from new to R− (blue to green) is induced by familiarity only. (D) Normal density functions showing a shift of R+/R− relative to new stimuli. (E and F) Same plots for sessions with chance level performance. There is no significant difference. The cdfs of R+ (n = 127) and R− (n = 254) overlap completely but are different from the cdf of new trials (blue vs. red/green, P < 1 × 10−9). (G and H) activity during retrieval 24 h later did not distinguish successful (n = 226) from failed (n = 114) recollection. Errors are ± SEM.

Is there a significant difference between recollected and not recollected stimuli for patients whose behavioral performance was near chance levels? We found that the mean response to recollected and not recollected stimuli did not differ (Fig. 3 E and F; 45% vs. 46%, P = 0.93). This is further illustrated by the complete overlap of the distribution of responses to R+ and R− stimuli (Fig. 3F, P = 0.53). (This is also true if hippocampal neurons are evaluated separately, SI Fig. 7B). Thus, the difference (22%) associated with good recollection performance was abolished in the subjects with poor recollection memory.

Was the neuronal response still enhanced by good recollection performance after the 24-h time delay? Subjects in the 24-h delay group had good recollection performance (66%) that was not significantly different from their performance on the 30-min delay period. Thus, information about the source of the stimulus was available to the subject. Surprisingly, however, we found that the firing difference between recollected and not recollected items was no longer present (Fig. 3 G and H). Firing differed by 59% for recollected items compared with 61% for not recollected items (Fig. 3 G and H; P = 0.81). [This is also true if hippocampal neurons are evaluated separately (SI Fig. 7C)]. This lack of difference between R+ and R− items is in contrast to the 30-min R+ delay sessions, where a difference of 22% was observed.

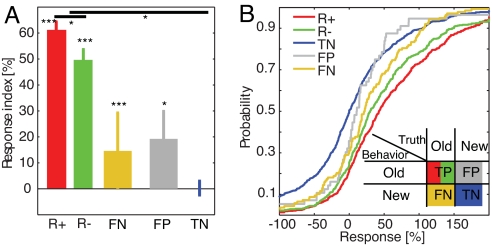

Neural Activity During Recognition Errors.

What was the neural response evoked by stimuli that were incorrectly recognized by the subject? Patients could make two different types of recognition errors: (i) not remembering an item [false negative (FN)] and (ii) identifying a new picture as an old picture (FP). Here, we pooled all same-day sessions (13 sessions from eight patients) regardless of recollection performance. First, we focused on the FNs. We hypothesized that if the neuronal activity truly reflects the behavior, the response should be equal to the response to correctly identified novel stimuli. However, if the neurons we recorded from represent a general representation of memory strength, we expect to see a response that is smaller than that observed for correctly recognized items. Indeed, we found that the mean response during “forgot” error trials was 14 ± 3% (Fig. 4A, yellow), significantly different from the response to novel stimuli [Fig. 4B, blue vs. yellow; P < 1 × 10−4, Kolmogorov–Smirnov (ks) test]. It was also significantly weaker when compared with all correctly recognized items (Fig. 4B, yellow vs. green and red, P ≤ 0.05, ks test, Bonferonni-corrected). What was the response to stimuli that were incorrectly identified as familiar? We hypothesized that if the FPs represent responses that were truly wrongly identified as old (rather than an accidental button press), we would observe a neuronal response that was significantly different from that observed for novel items. Indeed, we found that the response to FPs was significantly different from 0 and from the response to novel stimuli (Fig. 4B, blue vs. gray; ks test P = 0.007). The response to FPs and FNs was not significantly different (Fig. 4B, gray vs. yellow; ks test, P = 0.14). (For the previous analysis we pooled neurons recorded from the hippocampus and the amygdala. The same response pattern holds, however, if hippocampal units are evaluated separately; SI Fig. 7D). This pattern of activity during behavioral errors is consistent with the idea that the neurons represent memory strength on a continuum.

Fig. 4.

Activity during errors reflects true memory rather than behavior. All 30-min sessions are included for this analysis. (A) Neural response. (B) Response plotted as a cdf. Notice the shift from novel to false negatives (P < 1 × 10−4): The same behavioral response (novel) leads to a different neural response still differed significantly when compared with real novel pictures. (Inset) Different possible trial types. Errors are ± SEM; n is nr of trials (759, 521, 1,372, 148, and 56, respectively; 13 sessions, eight patients).

Discussion

We analyzed the spiking activity of neurons in the human MTL during retrieval of declarative memories. We found that the neural activity differentiated between stimuli that were only recognized as familiar and stimuli for which (in addition) the spatial location could be recollected. Further, we found that the same neural activity was also present during behavioral errors, but with reduced amplitude. This data are compatible with a continuous signal of memory strength: the stronger the neuronal response, the better the memory. Forgotten stimuli have the weakest memory strength and stimuli that are only recognized but not recollected have medium strength. The strongest memory (and thus neuronal response) is associated with stimuli that are both recognized and recollected.

We used the spatial location of the stimuli during learning as an objective measure of recollection. An alternative measure is the “remember/know” paradigm (9). However, this measure suffers from subjectivity and response bias. Alternative theories hold that remember/know judgments reflect differences in memory strength rather then different recognition processes (15). Thus, we chose to use an explicit measure of recollection instead.

We tested two different time delays: same-day (30 min) and overnight (24 h). Despite good behavioral performance on both days, the neuronal firing only distinguished between R+ and R− trials on the same day. Thus, although the information was accessible to the patient, it was not present anymore in the form of spike counts—at least in the neurons from which we recorded. In contrast, information about the familiarity of the stimulus was still present at 24 h, and spike counts distinguished equally well between familiar and novel pictures (SI Fig. 8). Although the lack of recordings from cortical areas prevents us from making any definitive claims about this phenomena, it is nevertheless interesting to note that these two components of memory (familiarity and recollection) may be transferred from the MTL to other brain areas with different time courses. Indeed, recent data investigating the replay of spatial sequences by hippocampal units suggest that episodic memories could be transferred to cortex very quickly. Replay starts in quiet (but awake) periods shortly after encoding and continues during sleep (16).

We found that the responses described here can be found both in the hippocampus and the amygdala. Previous human studies have similarly found that visual responses can be found in both areas with little difference (2, 17). Similarly, recordings from monkeys have also identified amygdala neurons that (i) respond to novelty and (ii) habituate rapidly (18). It has long been recognized that the amygdala plays an important role in rapid learning. This is exemplified by its role in conditioned taste aversion, which is acquired in a single trial, is strongly novelty-dependent and requires the amygdala (19).

The subset of neurons that we selected for analysis exhibited a significant firing difference between old and new stimuli during the stimulus presentation period. This selection criteria allows for a wide variety of response patterns. The simplest case is when a neuron increases firing to one category and remains at baseline for the other. But more complex patterns are possible: the neuron could decrease firing for one category and remain at baseline for the other. Or the response could be bimodal, e.g., increase to one category and decrease to the other. To further investigate this, we compared firing during the stimulus period to the prestimulus baseline (see SI Table 2 and SI Discussion). Fifty-four percent of the neurons changed activity significantly for the trial type for which the unit was classified (i.e., old trials for familiarity neurons). Ninety-two percent of the neurons change their firing rate relative to baseline for either type of trial (e.g., decrease in firing rate of familiarity neurons for new trials). Thus, 38% of the neurons signal information by a significant firing decrease, and 8% of the neurons have a bimodal response that individually is not significantly different from baseline. We maintain that the firing behavior of this 8% group contains information about the novelty of the stimulus, even though the responses are not significantly different from baseline. Below, we describe several scenarios by which this 8% population might contain decodable information. We repeated our analysis with only the remaining 92% of neurons to assess whether our previous conclusions, based on the entire data-set, still hold true. We found that all results remain valid: The within-repeated ANOVA for the 30-min R+ group revealed a significant difference of new vs. R− and R+ vs. R− for both novelty (P < 1 × 10−4 and P = 0.03, respectively) and familiarity units (P = 0.05 and P = 0.02, respectively). Similarly, the per-neuron (n = 42 neurons, P = 0.03) and the per-trial comparison (P = 0.01) remained significant (compare to Fig. 3 A–C). Considering only hippocampal neurons that fire significantly different from baseline, the difference between R+ and R− (P = 0.04), R− and new (P < 0.001) and new vs. FNs (P = 0.003) remained significant (all are tailed ks tests; compare with SI Fig. 7A). All R+ vs. R− comparisons for the 30-min R− and 24-h sessions remained insignificant.

How might a neural network decode the information about a stimulus if it is signaled with no change or a decrease in firing rate? One obvious possibility is by altering excitatory-inhibitory network transmission: If the neuron that signals with a decrease in firing is connected to an inhibitory unit that in turn inhibits an excitatory unit, the excitatory neuron would only fire if the input neuron decreases its firing rate. A similar network could be used to decode information that is present in an unchanged firing rate. How can a network decode information from units that are significantly different new vs. old but not relative to baseline? One possibility is that the network gets an additional input that signals the onset of the stimulus. Thus, it knows which time period to extract. Also, although we can only listen to one single neuron, a readout mechanism gets input from many neurons and can thus read signals with much lower signal-to-noise ratios.

Models of Memory Retrieval.

It is generally accepted that recognition judgments are based on information from (at least) the two processes of familiarity and recollection. How these two processes interact, however, is unclear. Here, we have shown that both components of memory are represented in the firing of neurons in the hippocampus and amgydala. Clearly, the neuronal firing described here cannot be attributed to one of the two processes exclusively. Rather, the neuronal firing is consistent with both components summing in an additive fashion.

This result has implications for models of memory retrieval. There are two fundamentally different models of how familiarity and recollection interact. The first (i) model proposes that recognition judgments are either based on an all-or-nothing recollection process (“high-threshold”) or on a continuous familiarity process. Only if recollection fails is the familiarity signal considered (10, 20). An alternative (ii) model is that both recollection and familiarity are continuous signals that are combined additively to form a continuous signal of memory strength that is used for forming the recognition judgment (21). Our data are more compatible with the latter model (ii). We found that the stronger the firing of familiarity neurons, the more likely that recollection will be successful. However, the ability to correctly decode the familiarity of the stimulus does not depend on whether recollection will be successful. This is demonstrated by the single-trial decoding (SI Fig. 8): Recognition performance only marginally depends on whether the stimulus will be recollected or not. Also, the familiarity of the stimulus can be decoded equally well in patients that lack the ability to recollect the source entirely. Thus, the firing increase caused by recollection is additive and uncorrelated with the familiarity signal. This is incompatible with the high-threshold model, which proposes that either the familiarity or the recollective process is engaged. The neurons described here distinguished novel from familiar stimuli regardless of whether recollection was successful. Thus, the information carried by these neurons does not exclusively present either index. Rather, the signal represents a combination of both.

Neuronal Firing During Behavioral Errors.

What determines whether a previously encountered stimulus is remembered or forgotten? We found that stimuli that were wrongly identified as novel (forgotten old stimuli) still elicited a significant response. We found (6) that this response allows single-trial decoding with performance significantly better than the patient's behavior. Thus, information about the stimulus is present at the time of retrieval. This implies that the stimuli were (at least to some degree) properly encoded and maintained. However, the neural activity associated with false negative recognition responses was weaker than the responses to correctly recognized but not recollected stimuli (≈60% reduced, Fig. 4A). The response to false negatives fell approximately in between the response to novel and correctly recognized familiar stimuli (Fig. 4B). The neuronal response can thus be regarded as an indicator of memory strength. The memory strength for not remembered items is less than for remembered items but it is still larger than zero. However, the memory strength was not strong enough to elicit a “familiar” response. Others (22) have also found neurons that indicate, regardless of behavior, the “true memory” associated with a stimulus. Thus, the neurons considered here likely signal the strength of memory that is used for decision making rather than the decision itself.

False recognition is the mistaken identification of a new stimulus as familiar. The false recognition rate in a particular experiment is determined by many factors, including the individual bias of the subject and the perceptual similarity of the stimuli (gist) or their meaning (for words). Here, we found that neurons responded similarly (but with reduced amplitude) to stimuli that were wrongly identified as familiar when compared with truly familiar stimuli. Thus, from the point of view of the neuronal response, the stimuli were coded as somewhat familiar. As such, it seems that the behavioral error possesses a neuronal origin in the very same memory neurons that respond during a correct response—and can thus not be exclusively attributed to simple errors, such as pressing the wrong button. MTL lesions result in severe amnesia, measured by a reduction in the TP rate and an increased FP rate relative to controls. However, in paradigms where normal subjects have high FP rates due to semantic relatedness to studied words, amnesics have lower FP rates than controls (23). Thus, in some situations, a functional MTL can lead to more false memory. Similarly, activation of the MTL (and particularly the hippocampus) during false memory has also been observed with neuroimaging (24). This and our finding that neuronal activity does consider such stimuli as familiar suggests that FPs are not due to errors in decision making.

Methods

Subjects and Electrophysiology.

Subjects were 10 patients (6 male, mean age 33.7). Informed consent was obtained, and the protocol was approved by the Review Boards of the California Institute of Technology and Huntington Memorial Hospital. Activity was recorded from microwires embedded in the depth electrodes (6). Single-units were identified by using a template matching method (25).

Experiment.

An experiment consisted of a learning and retrieval block with a delay of either 0.5 or 24 h in between. During learning, 12 unique pictures were presented in random order. Each picture was presented for 4 s in one of the four quadrants of a computer screen. We asked patients to remember both which pictures they had seen and where on the screen they had seen them. To ensure alertness, patients were asked to indicate where the picture was after each presentation during learning.

In each retrieval session, 24 pictures (12 new, 12 old, randomly intermixed) were presented at the center of the screen. Afterward, the patient was asked whether he/she had seen the picture before or not. If the answer was “old,” the question “Where was it?” was asked (see Fig. 1A). During the task, no feedback was given.

Data Analysis.

A neuron was considered responsive if the firing rate in response to correctly recognized old vs. new stimuli was significantly different. We tested in 2-s bins (0–2, 2–4, and 4–6 s relative to stimulus onset). A neuron was included if its activity was significantly different in at least one of these three bins. We used a bootstrap test (P < = 0.05, B = 10,000, two-tailed) of the number of spikes fired to new vs. old stimuli. We assumed that each trial is independent; i.e., the order of trials does not matter. Neurons with more spikes in response to new stimuli were novelty neurons, whereas neurons with more spikes in response to old stimuli were familiarity neurons.

We also used an aggregate measure of activity that pools across neurons. For each trial, we counted the number of spikes during the entire 6-s poststimulus period. The response index (Eq. 1) quantifies the response during trial i relative to the mean response to novel stimuli.

R(i) is negative for novelty detectors and positive for familiarity detectors (on average). R(i) was multiplied by −1 if the neuron is classified as a novelty neuron. Notice that the factor −1 depends only on the unit type. Thus, negative R(i) values are still possible.

The cdf was constructed by calculating for each possible value x of the response index how many examples are smaller than x. That is, F(x) = P(X ≤ x), where X is a vector of all response index values.

All statistical tests are t tests unless stated otherwise. Trial-by-trial comparisons of the response index are Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. All errors are ± SE unless indicated otherwise.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank L. Squire, G. Kreiman, F. Mohrman and W. Einhaeuser for discussions; all patients for their participation; and the staff of the Huntington Hospital for their support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0706015105/DC1.

References

- 1.Heit G, Smith ME, Halgren E. Nature. 1988;333:773–775. doi: 10.1038/333773a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreiman G, Koch C, Fried I. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:946–953. doi: 10.1038/78868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolls ET. Hippocampus. 1999;9:467–480. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:4<467::AID-HIPO13>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight R. Nature. 1996;383:256–259. doi: 10.1038/383256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang JZ, Brown MW. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:657–676. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutishauser U, Mamelak AN, Schuman EM. Neuron. 2006;49:805–813. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viskontas IV, Knowlton BJ, Steinmetz PN, Fried I. J Cognitive Neurosci. 2006;18:1654–1662. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.10.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halgren E, Wilson CL, Stapleton JM. Brain Cogn. 1985;4:287–295. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(85)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eldridge LL, Knowlton BJ, Furmanski CS, Bookheimer SY, Engel SA. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1149–1152. doi: 10.1038/80671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yonelinas AP. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2001;356:1363–1374. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manns JR, Hopkins RO, Reed JM, Kitchener EG, Squire LR. Neuron. 2003;37:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wais PE, Wixted JT, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Neuron. 2006;49:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stark CEL, Bayley PJ, Squire LR. Learn Mem. 2002;9:238–242. doi: 10.1101/lm.51802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hampton RR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5359–5362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071600998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donaldson W. Mem Cogn. 1996;24:523–533. doi: 10.3758/bf03200940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster DJ, Wilson MA. Nature. 2006;440:680–683. doi: 10.1038/nature04587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried I, MacDonald KA, Wilson CL. Neuron. 1997;18:753–765. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson FA, Rolls ET. Exp Brain Res. 1993;93:367–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00229353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamprecht R, Dudai Y. In: The Amygdala. Aggleton JP, editor. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2000. pp. 311–329. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandler G. Psychol Rev. 1980;87:252–271. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wixted JT. Psychol Rev. 2007;114:152–176. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messinger A, Squire LR, Zola SM, Albright TD. Neuron. 2005;48:359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schacter DL, Dodson CS. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2001;356:1385–1393. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schacter DL, Reiman E, Curran T, Yun LS, Bandy D, McDermott KB, Roediger HL. Neuron. 1996;17:267–274. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutishauser U, Schuman EM, Mamelak AN. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;154:204–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.