Abstract

We report a case of Lasiodiplodia theobromae pneumonia in a patient who died 14 days after cadaveric-liver transplantation. His condition was complicated by Enterococcus faecium peritonitis. Direct microscopy analysis of the bronchoalveolar lavage specimens showed septate hyphae. A dematiaceous mold was recovered and identified as L. theobromae by microscopic morphology and EF1α gene sequencing.

CASE REPORT

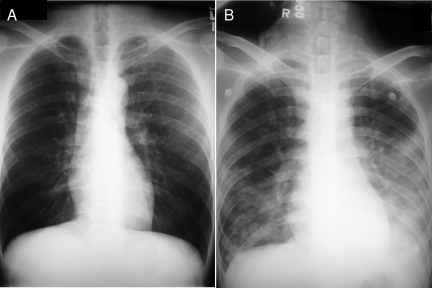

A 45-year-old Chinese man was admitted to the hospital because of severe sepsis 14 days after cadaveric-liver transplantation. He had hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed in July 2006. Cadaveric-liver transplantation was performed in mainland China in September 2006 and was complicated by portal vein thrombosis and liver failure. He was transferred back to Hong Kong 14 days after the transplantation. Examination showed a tense abdomen and bilateral, coarse crepitations over both sides of the chest. The total white cell count was 22.5 × 109/liter (neutrophil count, 21.2 × 109/liter), the hemoglobin level was 9.7 g/dl, and the platelet count was 34 × 109/liter. Other laboratory findings included the following levels in serum: creatinine, 463 μmol/liter; urea, 49.8 mmol/liter; albumin, 22 g/liter; globulin, 28 g/liter; bilirubin, 217 μmol/liter; alkaline phosphatase, 213 IU/liter; aspartate aminotransferase, 57 IU/liter; and alanine aminotransferase, 34 IU/liter. A chest radiograph showed air space shadows over both lungs (Fig. 1). Computed tomography scanning of the abdomen revealed portal vein thrombosis and ascites. An analysis of a direct KOH smear of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid showed numerous leukocytes and septate hyphae. A Gram smear analysis and Ziehl-Neelsen staining showed no bacteria or acid-fast bacilli. Empirical treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam, vancomycin, and caspofungin was given. An emergency laparotomy was performed and revealed portal vein and superior mesenteric vein thrombosis and a gangrenous descending colon. Peritoneal fluid showed an elevated cell count of 4,380 × 106/liter and yielded heavy growth of Enterococcus faecium. A peritoneal fluid culture for fungi was negative. Blood cultures for bacteria and fungi were negative. The patient succumbed 11 h after the operation. The culture of two bronchoalveolar lavage specimens taken before and after the operation did not produce any bacteria but yielded heavy growth of a dematiaceous mold after 3 days of incubation at 37°C.

FIG. 1.

Chest radiographs of the patient's lungs taken 2 months before admission (A) and upon admission (B). The chest radiograph taken upon admission showed air space shadows over both lungs.

Microbiological methods.

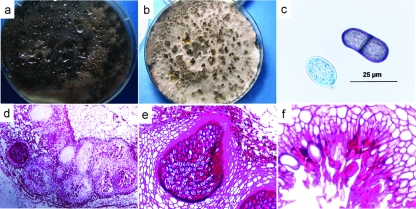

Clinical specimens were collected and handled according to standard protocols and inoculated onto blood, chocolate, and MacConkey agars for bacterial cultures and onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) for fungal culture. Bacteria were identified by standard conventional phenotypic methods (7). On SDA, the mold grew as cottony colonies that became dark gray within 7 days (Fig. 2a). Growth at 37°C was more rapid than that at 25°C. Microscopic examination after lactophenol cotton blue staining showed septate brown hyphae with a width of 6 μm. The mold was also grown on oatmeal agar (prepared in-house) and incubated in sunlight to stimulate sporulation. Colonies produced hairy, dark brown structures (Fig. 2b) that were determined to be pycnidia. Conidia released from the pycnidia were hyaline and nonseptate when young but were septate and brown, with longitudinal striations, when mature (Fig. 2c). Pycnidia were sometimes produced in aggregates as revealed in periodic acid-Schiff-stained histological sections of the mold on oatmeal agar (Fig. 2d). Examination under higher magnification showed a pycnidium with an obvious neck (Fig. 2e) and conidiogenous cells and paraphyses (sterile filaments among conidia) lining the internal wall (Fig. 2f). The fungus was identified as Lasiodiplodia theobromae (3).

FIG. 2.

Phenotypic characterization of the mold. (a) Seven-day culture of the mold on SDA, showing dark gray cottony colonies. (b) Two-week culture of the mold on oatmeal agar incubated in sunlight, showing hairy, dark brown pycnidia. (c) Young, nonseptate, hyaline conidia and old, septate, brown conidia with longitudinal striations released from the pycnidia. (d) Periodic acid-Schiff-stained histological sections of the mold, showing aggregates of pycnidia. (e and f) Pycnidium with an obvious neck and conidiogenous cells and paraphyses (sterile filaments among conidia) lining the internal wall.

ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rRNA gene cluster sequencing and phylogenetic characterization.

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1)-5.8S-ITS2 rRNA gene cluster (ITS) of the isolate were performed according to a published protocol by using ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) (GIBCO BRL, Rockville, MD) as the PCR and sequencing primers (19). PCR analysis of the ITS region showed a band at about 500 bp. The sequence of the PCR product was compared with sequences of closely related species listed in the GenBank database by multiple-sequence alignment using ClustalX 1.83 (17). The ITS sequence of the case isolate was identical to that of Botryosphaeria rhodina (GenBank accession no. DQ008312) and differed by six bases (2%) from that of Lasiodiplodia theobromae (GenBank accession no. AY160214), the anamorph of B. rhodina. Comparison with sequences of newly described Lasiodiplodia species revealed differences in 8 bases (2%) relative to the sequence of L. gonubiensis (GenBank accession no. AY639595), 9 bases (2%) relative to that of L. rubropurpurea (GenBank accession no. DQ103554), 13 bases (3%) relative to that of L. venezuelensis (GenBank accession no. DQ103548), and 18 bases (4%) relative to that of L. crassispora (GenBank accession no. DQ103552).

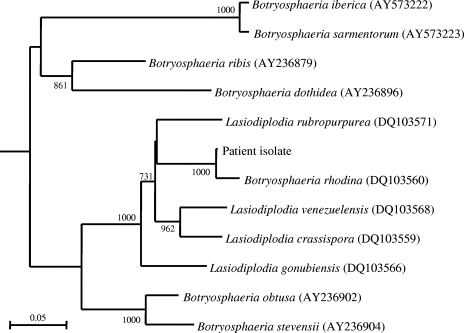

Partial EF1α gene sequencing and phylogenetic characterization.

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing of a 289-bp fragment of the EF1α gene of the isolate were performed according to a published protocol by using EF1-728F (5′-CATCGAGAAGTTCGAGAAGG-3′) and EF1-986R (5′-TACTTGAAGGAACCCTTACC-3′) (GIBCO BRL, Rockville, MD) as the PCR and sequencing primers (2). PCR analysis of the EF1α gene showed a band at about 300 bp. The sequence was compared with those of species listed in the GenBank database by using ClustalX 1.83 (17). Phylogenetic relationships were determined using the neighbor-joining method (14) (Fig. 3). A total of 308 nucleotide positions were used. The EF1α gene sequence of the case isolate differed by two bases (1%) from that of B. rhodina (GenBank accession no. DQ103560). Comparison with sequences of newly described Lasiodiplodia species revealed differences in 10 bases (5%) relative to the sequence of L. venezuelensis (GenBank accession no. DQ103568), 12 bases (6%) relative to that of L. crassispora (GenBank accession no. DQ103559), 16 bases (8%) relative to that of L. rubropurpurea (GenBank accession no. DQ103571), and 17 bases (8%) relative to that of L. gonubiensis (GenBank accession no. DQ103566).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of the mold from our patient to closely related species, inferred from EF1α gene sequence data (308 nucleotide positions) by the neighbor-joining method and rooted using Aspergillus clavatus (XM_001269545). The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 10 bases. Numbers at nodes indicate levels of bootstrap support calculated from 1,000 trees. All names and accession numbers are given as cited in the GenBank database.

L. theobromae, known for almost a century, is the anamorph of B. rhodina, a member of the subphylum Pezizomycotina of Ascomycota and a common plant pathogen in tropical countries. It is often isolated from woody plants and is associated with rot in fruits and other plants and with wood staining (10). L. theobromae was the only species of Lasiodiplodia known until recently, when four additional species were described. These include L. gonubiensis, described in 2004 (8), and L. venezuelensis, L. crassispora, and L. rubropurpurea, described in 2007, based on results from ITS and EF1α sequence analysis and morphology (2). These novel species are considered very rare and have limited geographic distributions (2, 8).

Human infections are extremely rare. We report a case of pneumonia caused by L. theobromae. The clinical significance of L. theobromae was evident from observations of numerous leukocytes and septate hyphae on a direct KOH smear and the isolation of a pure growth of this microorganism from two independent bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. Fifteen cases of L. theobromae infection have been reported previously (Table 1) (4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18). Ten were in males and five were in females, with a median age of the patients of 48 years (range, 14 to 69 years). Eight cases were in tropical countries in Asia (India, Cambodia, and the Philippines) and Central and South America (Columbia, Guyana, and Jamaica), in correlation with the fungus's being a ubiquitous tropical and subtropical plant pathogen. Twelve cases involved ophthalmic infections, most notably keratitis, with the first two cases reported in 1967 (11). Only one patient was reported to have a major underlying disease (1). For keratitis and corneal ulcers, local topical treatment was the main therapy, whereas both systemic and local treatments were used for endophthalmitis. Three other patients had onychomycosis, a buttock abscess, and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis. The excision of the diseased nail, drainage and debridement, and the excision of the ulcer were performed in the respective cases. None of the patients died, in contrast to our patient, who succumbed rapidly despite systemic caspofungin treatment. In previous cases, infections of the eyes, skin, and soft tissues were believed to be the result of direct inoculation of the fungus. In the patient in the present study, the mode of acquisition of the fungus remains enigmatic. Inhalation seems highly unlikely because the conidia of this fungus are borne inside pycnidia and are released in a slimy mass. We speculate that the patient may have consumed longan (Dimocarpus longan), a very popular fruit in southern China during summertime, well-known to be often infected with L. theobromae. Alternatively, the fungus may have been acquired from the cadaveric transplanted liver and may have invaded the lung via the bloodstream.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients with L. theobromae infections reported in the literature

| Patient no. | Reference | Geographical region | Sexa and age (yrs) | Underlying condition | Clinical specimen(s) positive for L. theobromae | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | India | M, 31 | Not mentioned | Corneal scrapings from right eye | Corneal ulcer | Potassium iodide, nystatin (Mycostatin), topical copper sulfate drops and sodium propionate ointment, mydriatic drops | Corneal perforation |

| 2 | 11 | India | F, 30 | Not mentioned | Corneal scrapings from right eye | Corneal ulcer | Potassium iodide, nystatin, topical copper sulfate drops and sodium propionate ointment, mydriatic drops | Corneal perforation |

| 3 | 5 | Not mentioned | M, 48 | None | Corneal scrapings from right eye | Keratitis | Local iodides; cauterization of ulcer and conjunctival flap | Remission |

| 4 | 18 | Philippines | M, 32 | None | Corneal scrapings from left eye | Keratitis and corneal abscess | Chloramphenicol drops, topical dexamethasone-neomycin-polymyxin, amphotericin B injection, sodium ethylmercurithiosalicylate ointment, mydriatic drops; superficial keratectomy, peripheral iridectomy, and lens extraction | Residual irritation of left eye |

| 5 | 12 | United States | M, 58 | None | Corneal scrapings from left eye | Keratitis | Topical amphotericin B and natamycin ointment | Remission |

| 6 | 12 | United States | M, 14 | None | Corneal scrapings from right eye | Keratitis | Bacitracin-neomycin-polymyxin ophthalmic drops | Remission |

| 7 | 12 | United States | M, 19 | None | Corneal scrapings from left eye | Keratitis | Topical neomycin drops, topical 5% natamycin suspension, and subconjunctival amphotericin B injections | Remission |

| 8 | 12 | United States | F, 69 | None | Corneal scrapings from left eye | Keratitis | Subconjunctival gentamicin, topical sulfacetamide and prednisolone drops, topical 5% natamycin drops; therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty | Remission |

| 9 | 13 | Colombia | F, 32 | None | Nail of right big toe | Onychomycosis | Excision of diseased nail | Remission |

| 10 | 4 | Japan | M, 54 | None | Corneal scrapings from left eye | Corneal ulcer | Oral ketoconazole and intravenous miconazole | Remission |

| 11 | 9 | United States | M, 62 | Not mentioned | Corneal scrapings | Keratitis and endophthalmitis | Subconjunctival and systemic amphotericin B, topical natamycin; enucleation | Enucleation |

| 12 | 16 | India | M, 55 | None | Corneal scrapings from right eye | Keratitis | Antifungals (regimens not mentioned); penetrating keratoplasty | Remission |

| 13 | 6 | Cambodia | F, 40 | None | Fluid and biopsy specimen from right-buttock abscess | Subcutaneous abscess | Drainage and debridement | Remission |

| 14 | 1 | Guyana | M, 57 | Myeloid leukemia | Aqueous corneal scrapings, vitreous aspirate, cornea, ciliary body, iris, and retina from left eye | Keratitis and endophthalmitis | Intravitreal itraconazole, prednisone, and amphotericin; enucleation | Enucleation |

| 15 | 15 | Jamaica | F, 50 | None | Excisional biopsy specimen of right-leg ulcer | Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis | Excision of ulcer | Remission |

| 16 | Present study | Hong Kong | M, 45 | Previous liver transplantation | Bronchoalveolar lavage specimens | Pneumonia | Caspofungin | Death |

M, male; F, female.

Partial EF1α sequencing is more reliable than ITS sequencing for identifying L. theobromae to the species level (2). As shown here, ITS sequencing was not sufficiently discriminatory to distinguish among Lasiodiplodia species. The ITS sequence of the patient isolate differed by six bases from that of another strain of L. theobromae but differed by only eight bases from that of a strain of L. gonubiensis. It can be confidently concluded that the isolate was L. theobromae from the EF1α gene sequence, which has been demonstrated to be useful for differentiating the Lasiodiplodia species (2), and the results were compatible with those obtained by phenotypic identification. Phenotypic identification requires expertise and experience for the recognition of characteristic microscopic features of different types of molds, but gene sequencing offers a precise and objective way of determining the identities of difficult fungi.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The ITS sequence and the partial EF1α gene sequence of the isolate have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers EF622017 and EF622018. The fungus culture has been deposited in the CBS culture collection.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the University Development Fund and the Committee for Research and Conference Grants, The University of Hong Kong.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borderie, V. M., T. M. Bourcier, J. L. Poirot, M. Baudrimont, P. Prudhomme de Saint-Maur, and L. Laroche. 1997. Endophthalmitis after Lasiodiplodia theobromae corneal abscess. Graefe's Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 235259-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess, T. I., P. A. Barber, S. Mohali, G. Pegg, W. de Beer, and M. J. Wingfield. 2006. Three new Lasiodiplodia spp. from the tropics, recognized based on DNA sequence comparisons and morphology. Mycologia 98423-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Hoog, G. S., J. Guarro, J. Gene, and M. J. Figueras (ed.). 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd ed., p. 325. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 4.Ishibashi, Y., and Y. Matsumoto. 1984. Intravenous miconazole in the treatment of keratomycosis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 97646-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laverde, S., L. H. Moncada, A. Restrepo, and C. L. Vera. 1973. Mycotic keratitis: 5 cases caused by unusual fungi. Sabouraudia 11119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maslen, M. M., T. Collis, and R. Stuart. 1996. Lasiodiplodia theobromae isolated from a subcutaneous abscess in a Cambodian immigrant to Australia. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 34279-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray, P. R., E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. L. Landry, and M. A. Pfaller (ed.). 2007. Manual of clinical microbiology, 9th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 8.Pavlic, D., B. Slippers, T. A. Coutinho, M. Gryzenhout, and M. J. Wingfield. 2004. Lasiodiplodia gonubiensis sp. nov., a new Botryosphaeria anamorph from native Syzygium cordatum in South Africa. Stud. Mycol. 50313-322. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pflugfelder, S. C., H. W. Flynn, Jr., T. A. Zwickey, R. K. Forster, A. Tsiligianni, W. W. Culbertson, and S. Mandelbaum. 1988. Exogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology 9519-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Punithalingam, E. 1976. CMI descriptions of pathogenic fungi and bacteria, no. 519. Botryodiplodia theobromae. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, Surrey, United Kingdom.

- 11.Puttana, S. T. 1967. Mycotic infections of the cornea. J. All-India Ophthalmol. Soc. 1511-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rebell, G., and R. K. Forster. 1976. Lasiodiplodia theobromae as a cause of keratomycoses. Sabouraudia 14155-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Restrepo, A., M. Arango, H. Velez, and L. Uribe. 1976. The isolation of Botryodiplodia theobromae from a nail lesion. Sabouraudia 141-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Evol. Biol. 4406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summerbell, R. C., S. Krajden, R. Levine, and M. Fuksa. 2004. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Lasiodiplodia theobromae and successfully treated surgically. Med. Mycol. 42543-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas, O. A., T. Kuriakose, M. P. Kirupashanker, and V. S. Maharajan. 1991. Use of lactophenol cotton blue mounts of corneal scraping as an aid to the diagnosis of mycotic keratitis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 254876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valenton, M. J., M. G. Rinaldi, and E. E. Butler. 1975. A corneal abscess due to the fungus Botryodiplodia theobromae. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 10416-418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White, T. J., T. Bruns, S. Lee, and J. W. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, p. 315-322. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, Inc., New York, NY.