Abstract

Enterovirus infections were investigated with special emphasis on performing rapid molecular identification of enterovirus serotypes responsible for aseptic meningitis directly in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Enterovirus genotyping was carried out directly with specimens tested for the diagnostic procedure, using two seminested PCR assays designed to amplify the complete and partial gene sequences encoding the VP1 and VP4/VP2 capsid proteins, respectively. The method was used for identifying the enterovirus serotypes involved in meningitis in 45 patients admitted in 2005. Enterovirus genotyping was achieved in 98% of the patients studied, and we obtained evidence of 10 of the most frequent serotypes identified earlier by genotyping of virus isolates. The method was applied for the prospective investigation of 54 patients with meningitis admitted consecutively in 2006. The enterovirus serotypes involved were identified with the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 52 patients (96%) and comprised 13 serotypes within the human enterovirus B species and 1 within the human enterovirus A species. The three most common serotypes were echovirus 13 (E13; 24%), E6 (23%), and coxsackievirus B5 (11.5%), a pattern different from that observed in 2005. Genotyping of virus isolates was also performed in 35 patients in 2006 (meningitis, n = 31; other diseases, n = 4). By comparison, direct genotyping in CSF yielded a more complete pattern of enterovirus serotypes, thereby allowing the detection of rare serotypes: three less common serotypes (CB2, E21, and E27) were not detected by indirect genotyping alone. The study shows the feasibility of prospective enterovirus genotyping within 1 week in a laboratory setting.

Enterovirus infections comprise a wide spectrum of clinical presentations and diseases (35). As with poliomyelitis, the most problematic clinical syndromes caused by nonpolio enteroviruses (NPEV)—meningitis, encephalitis, and acute flaccid paralysis—result from infection of the central nervous system (CNS) and are major causes of illness and morbidity in both children and adults (57).

Enterovirus meningitis (also known as aseptic meningitis) is the most commonly observed CNS infection, and its clinical presentation varies with the patient's age and immune status (38, 39). It occurs typically during outbreaks (in restricted geographical areas or communities) in the summer and autumn, leading to increased admissions to hospital wards for short periods. Unlike meningitis, enterovirus encephalitis is a more severe acute illness with more long-term sequelae (16) and, while it is less frequently observed than meningitis, its frequency should not be underestimated. For instance, in the California Encephalitis Project, an enterovirus infection was detected in 25% of patients with a viral etiology; 24% had a herpes simplex virus type 1 infection (20). NPEV can also be responsible for acute flaccid paralysis, a syndrome that mimics poliomyelitis. In Europe, 84 NPEV associated cases were registered in 2005 by the Polio Lab Network (3).

Enteroviruses have a positive single-stranded RNA genome subjected to high mutation rates and frequent genetic recombination events (1, 17, 30-33, 37, 46-48, 58, 60, 61) and thereby display a great diversity (10, 41, 52, 55, 59). More than 90 serotypes have been characterized among the human enteroviruses (HEVs), but only 68 are recognized in the current taxonomy (62). They are divided into four species (HEV-A to -D), and the three poliovirus serotypes are closely related to NPEV serotypes included within the HEV-C species (11). According to the serotyping results of strains recovered from the stool and throat specimens of patients with EV meningitis, most serotypes are suspected of being involved in meningitis (50), but only some enterovirus serotypes have been responsible for large nationwide epidemics (8, 14, 15, 25, 26, 29, 67). However, the true involvement of the different enterovirus serotypes responsible for CNS infection is difficult to determine because enteroviruses are only rarely isolated from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients and molecular typing is not performed to identify enteroviruses directly.

Although detection of the 5′ noncoding region of the enterovirus genome in CSF is the gold standard for the diagnosis of enterovirus CNS infection and provides results in a clinically relevant time frame (51, 53, 56, 66), the genome region is inappropriate for enterovirus identification (52). Several molecular typing methods based on the amplification and sequencing of part of the VP1 coding region have been developed (12, 13, 22, 36, 43, 45, 49), but few of them have been used to identify enteroviruses directly in the CSF of patients (13, 23, 42, 64) and, to our knowledge, none have been prospectively used in a clinical diagnostic laboratory.

Using a species-specific (HEV-B) method, we previously performed an indirect genotyping assay (molecular identification of clinical viruses isolated in vitro) and showed that it was suitable for prospective identification of enterovirus strains recovered in patients with various diseases, including meningitis (36). The assay relied on a set of two primers with degenerate nucleotide positions designed to amplify the complete VP1 sequence of B species enteroviruses and was carried out in 3 weeks. Even when performed prospectively, indirect enterovirus genotyping is not appropriate in clinical situations that require rapid identification, such as severe presentations especially in neonates (38) or immunosuppressed patients (5, 7), putative nosocomial infections (6), or epidemiological studies aimed at determining whether a meningitis outbreak is caused by a new variant or serotype.

The aim of the present study was to perform the prospective identification of enteroviruses involved in CNS infections directly with the CSF specimens used for diagnosis within 5 days versus the 3 weeks needed for indirect genotyping. Using a seminested PCR derived from the indirect genotyping method, we prospectively carried out direct identification in CSF samples of patients admitted to our local University Hospital (Clermont-Ferrand, France) in 2006 and compared the genotyping results with those obtained with indirect genotyping during the same period. Enterovirus genotyping was achieved directly in CSF samples in 96.3% of the patients with meningitis in 2006; 13 serotypes were identified within the HEV-B species, and 1 serotype was identified within the HEV-A species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

All CSF specimens were collected from patients admitted to the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand, France. Throughout the text, the designation of the CSF specimens is given in the following format: number of the CSF sample-year of collection. For the virus isolates, the number is preceded by CF for Clermont-Ferrand.

Diagnosis of enterovirus meningitis was based on signs indicative of meningitis (fever, headache, photophobia, and/or nausea/vomiting, and/or stiffness of the neck), negative CSF culture for bacteria, and either a positive reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay result (see below) in the CSF or the isolation of an enterovirus in cell culture from a peripheral specimen (throat swabs or feces).

From January to December 2005, 77 inpatients were diagnosed as having enterovirus meningitis. The diagnostic RT-PCR was positive for 70 of 77 patients. Overall, 56 enterovirus isolates were recovered and identified prospectively in a previous study (36). In 45 of 77 patients with meningitis, the viral RNAs extracted from CSF specimens were stored at −80°C for future retrospective genotyping investigations.

In 2006, 61 inpatients received a clinical diagnosis of enterovirus meningitis and were enrolled consecutively during the study period from February to December (see Table 3). Detection of the viral RNA in the CSF was positive in 54 of 61 patients (88.5%), and in 24 of 54 patients an enterovirus was isolated from throat swabs (n = 20) or feces (n = 4). In 7 of 61 patients (11.5%), the diagnostic RT-PCR assay was either negative (n = 5) or not done (n = 2). During the study period, an enterovirus was also recovered in four patients with clinical signs of pneumopathy (n = 1) or diarrhea (n = 2) and in one healthy boy whose brother (patient P33 in Table 3) was included in the study with proven meningitis.

TABLE 3.

Prospective enterovirus genotyping in CSF specimens and isolates in 61 patients with meningitis in 2006a

| Patient | CSF specimens

|

Enterovirus isolates

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation | Highest scoring strains

|

Accession no. (CSF) | |||||||

| Accession no. | Designation | % nt sequence identityb | Typec | Designation | Type | Accession no. | |||

| P1 | 045067-06 | No amplification (PCR A and PCR B) | |||||||

| P2 | 089047-06 | AY919480 | Isolate 10496 | 91 (310) | E27 | AM711037 | |||

| P3 | 105003-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 96 (859) | E13 | AM711038 | |||

| P4 | 142037-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 86 (907) | E6 | AM711039 | |||

| P5 | 149036-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 85 (849) | E6 | AM711040 | |||

| P6 | 150001-06 | X90723 | isolate M1262 | 83 (480) | E25 | AM696268 | CF151101-06 | E25 | AM711079 |

| P7 | 150005-06 | AF295487 | 764/85 | 86 (571) | E21 | AM711041 | |||

| P8 | 157038-06 | AY896761 | EV6-14103-00 | 85 (422) | E6 | AM696269 | |||

| P9c | CF167067-06 | CB5 | AM711079 | ||||||

| P10 | 168005-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 96 (841) | E13 | AM711042 | |||

| P11 | 168007-06 | AY186745 | pMP1-24 | 82 (800) | CB1 | AM711043 | CF168014-06 | CB1 | AM711081 |

| P12 | 177089-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 96 (842) | E13 | AM711044 | |||

| P13 | 181093-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 86 (937) | E6 | AM711045 | CF180083-06 | E6 | AM711082 |

| P14 | 184041-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 86 (864) | E6 | AM711046 | |||

| P15 | 184046-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 86 (908) | E6 | AM711047 | |||

| P16 | 186055-06 | AY268575 | KOR-E13-02-34 | 95 (847) | E13 | AM711049 | |||

| P17 | 189004-06 | DQ092797 | Human CB-5 | 92 (847) | CB5 | AM711050 | |||

| P18 | 186037-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 86 (906) | E6 | AM711048 | CF189033-06 | E6 | AM711083 |

| P19 | 192009-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 96 (841) | E13 | AM711051 | |||

| P20 | 193076-06 | DQ092797 | Human CB-5 | 91 (857) | CB5 | AM711052 | |||

| P21 | 194031-06 | DQ092797 | Human CB-5 | 90 (858) | CB5 | AM711053 | |||

| P22 | 196007-06 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 97 (855) | E30 | AM711054 | CF196006-06 | E30 | AM711084 |

| P23 | 196008-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 86 (947) | E6 | AM711055 | |||

| P24 | 196009-06 | AY896761 | EV6-14103-00 | 85 (410) | E6 | AM696270 | |||

| P25 | 200001-06 | AB239987 | 501-5R/Mog/03 | 87 (404) | E25 | AM696271 | |||

| P26 | 200065-06 | AF081621 | NC95-2135 | 96 (390) | CB2 | AM711056 | |||

| P27 | 202075-06 | AB167991 | 03-158FCC2 | 91 (686) | CB5 | AM711057 | CF202075-06 | CB5 | AM711085 |

| P28 | 205064-06 | AB239987 | 501-5R/Mog/03 | 87 (377) | E25 | AM696272 | CF205083-06 | E25 | AM711086 |

| P29 | 206013-06 | AY896761 | EV6-14103-00 | 85 (421) | E6 | AM696273 | CF206019-06 | E6 | AM711087 |

| P30 | 207033-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 97 (835) | E13 | AM711058 | CF207006-06 | E13 | AM711088 |

| P31 | 207034-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 97 (835) | E13 | AM711059 | |||

| P32 | 208033-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 96 (861) | E13 | AM711060 | CF209038-06 | E13 | AM711088 |

| P33 | 209006-06 | AB126217 | HO786/Kanagawa/2003 | 96 (544) | EV71 | AM696274 | |||

| P34 | 209061-06 | AY896763 | CBV3-18219-02 | 91 (980) | CB3 | AM711061 | CF209062-06 | CB3 | AM711090 |

| P35 | 211014-06 | AY896761 | EV6-14103-00 | 84 (386) | E6 | AM696275 | CF212044-06 | E6 | AM711091 |

| P36 | 214014-06 | AB178768 | OC/01397 | 96 (884) | E13 | AM711062 | CF214017-06 | E13 | AM711092 |

| P37 | 214068-06 | DQ092797 | Human CB-5 | 90 (851) | CB5 | AM711063 | CF216024-06 | CB5 | AM711093 |

| P38 | 214088-06 | AF160018 | p234-pak92 | 93 (954) | CB4 | AM711064 | |||

| P39 | CF219051-06 | CB5 | AM711094 | ||||||

| P40 | 220005-06 | AY896761 | EV6-14103-00 | 85 (410) | E6 | AM696276 | CF219087-06 | E6 | AM711095 |

| P41 | 221007-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 97 (835) | E13 | AM711065 | |||

| P42 | 229025-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 83 (975) | E6 | AM711066 | CF230052-06 | E6 | AM711096 |

| P43 | CF235029-06 | E13 | AM711097 | ||||||

| P44 | 235076-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 97 (841) | E13 | AM711067 | CF235044-06 | E13 | AM711098 |

| P45 | 237015-06 | AY896765 | EV7-15936-01 | 83 (484) | E7 | AM696277 | |||

| P46 | CF246026-06 | E13 | AM711099 | ||||||

| P47 | 247016-06 | AY208092 | 99/00010-41 | 95 (972) | E18 | AM711068 | |||

| P48 | 263048-06 | AY896760 | EV6-10887-99 | 86 (917) | E6 | AM711069 | CF262045-06 | E6 | AM711100 |

| P49 | 271062-06 | AY208092 | 99/00010-41/99 | 94 (934) | E18 | AM711070 | CF272084-06 | E18 | AM711101 |

| P50 | 280036-06 | AB178768 | OC/01397 | 95 (891) | E13 | AM711071 | CF282003-06 | E13 | AM711102 |

| P51 | CF287012-06 | E18 | AM711103 | ||||||

| P52 | 293003-06 | AY919558 | Isolate 10569b | 88 (885) | E9 | AM711072 | CF293042-06 | E9 | AM711104 |

| P53 | 303018-06 | AY208092 | 99/00010-41/99 | 95 (981) | E18 | AM711073 | CF303024-06 | E18 | AM711105 |

| P54 | 312001-06 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 92 (860) | E30 | AM711074 | |||

| P55 | 312082-06 | DQ251322 | Glas12 | 93 (215) | Untyped | AM696278 | CF314038-06 | E25 | AM711106 |

| P56 | 326004-06 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 96 (839) | E13 | AM711075 | CF327002-06 | E13 | AM711107 |

| P57 | CF327034-06 | EV71 | AM696279 | ||||||

| P58 | 345042-0 | AF085363 | Strain Ohio-1 | 84 (956) | CB2 | AM711076 | |||

| P59 | 347020-06 | AF524866 | Strain Barty | 83 (1033) | E9 | AM711077 | |||

| P60 | 364004-06 | AF160018 | 9105net93 | 92 (951) | CB4 | AM711078 | |||

| P61 | CF356006-06 | CB4 | AM711108 | ||||||

Results obtained with VP4-VP2 sequences are indicated in italics. Results for patients with a negative (or not done) diagnostic RT-PCR in the CSF are indicated in boldface.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the length of the nucleotide (nt) sequence investigated by BLAST analysis.

E, echovirus; CB, coxsackievirus B; EV, enterovirus.

Diagnostic RT-PCR assays.

In 2005 and from January to May 2006 (the first seven patients hospitalized during the period of the prospective study), the positive detection of the enterovirus genome was obtained with the in-house real-time one-step RT-PCR assay described previously (4). In June 2006, a new procedure, NucliSens-EasyMag/EasyQ (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), was adopted in the laboratory for the diagnosis of enterovirus infections and used in 47 of 54 positive CSF specimens. The method allows automated extraction and a real-time NASBA detection of the viral RNA (19).

Virus isolation in cell culture.

Human lung embryonic fibroblasts (MRC5 cells; bioMérieux) and/or human epidermal carcinoma of the mouth (KB) cell lines were used for virus isolation from throat swabs and/or feces. Primary identification was based on the appearance of an enterovirus-like cytopathic effect and confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence assay as previously described (36). For patient P57 (Table 3), confirmation was made with the diagnostic RT-PCR because the indirect immunofluorescence assay result was negative.

Genotyping RT-PCR assays and nucleotide sequencing.

Synthesis of the cDNA was performed using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France) with random hexanucleotides at 2.5 ng/μl as primers, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each reaction was carried out in a 20-μl reaction mix containing 8 μl of viral RNA, 0.5 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate (Eurogentec, France), 2.5 μl of 5× reaction buffer, 0.01 M of dithiothreitol, 2 U of RNAseout (Invitrogen), and 10 U of reverse transcriptase. A total of 5 μl of the RT reaction mixture was used in subsequent assays.

Two different seminested PCR assays (PCR A and PCR B) were used in the study. PCR A and B were directed at the VP1 encoding sequence and at the genome segment comprising the VP4 and partial VP2 (5′ end) encoding genes, respectively. Primers used in the study are listed in Table 1. Primers HEVBS1695 and HEVBR132 were derived from the oligonucleotides ecox1 and ecox2 (6) previously tested on 43 EV isolates representing 18 different serotypes of the HEV-B species (accession numbers AJ131523, AJ241422 to AJ241456, AJ276624 to AJ276626, and AJ276812 to AJ276815) and were used in earlier studies (5, 8). Primers HEVBS1695 and HEVBR132 were first described for successful genotyping of 73 enterovirus isolates and amplified six additional serotypes in the HEV-B species (36).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primera | Sequence (5′-3′)b | Locationc | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEVBS1695* | CTTGTGCTTTGTGTCGGCRTGYAAYGAYTTYTCWG | 2375-2409 | 59.5 |

| HEVBR132* | GGTGCTCACTAGGAGGTCYCTRTTRTARTCYTCCCA | 3467-3432 | 61.2 |

| P1S1695S* | CTTGTGCTTTGTGTCGGC | 2375-2392 | 48.4 |

| P2R132S* | GGTGCTCACTAGGAGGTC | 3467-3450 | 50.2 |

| EV2C | CAATACGGCATTTGGACTTGAACTGTATG | 4443-4415 | 55.1 |

| 5NC63B** | CGGTACCYTTGTRCGCCTG | 64-82 | 52.6 |

| 5NCS663 | GCGGAACCGACTACTTTGGGTGTCCGTGTTTC | 538-568 | 61.4 |

| HEVR436** | CCCATGTCAGTCAGCGCATCIGGIARITTCCAIYACCAICC | 1210-1191 | 61.4 |

Primers previously described by Mirand et al. (36) or Bailly et al. (9) are indicated by one or two asterisks, respectively.

Sequences are written using standard nucleotide codes. R = A or G; Y = C or T; W = A or T; I = A, T, G, or C.

The positions are given relative to the genome of echovirus 30 strain Bastianni (AF311938).

All of the reaction mixtures had a final volume of 50 μl and contained 320 μM each of the deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 5 μl of the 10× reaction buffer, 400 nM each of the two oligonucleotide primers (see below), and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen S.A., Courtaboeuf, France).

First-round PCR A assays were performed with the reaction mixtures, including primers HEVBS1695 and EV2C (Table 1), and were run under the following conditions: 2 min at 94°C for denaturation, followed by 41 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 20 s at 58°C, and 1.5 min at 68.5°C, with a final 10 min at 68.5°C. The second-round PCR A contained 5 μl of the first-round PCR A amplicons and oligonucleotides HEVBS1695 and HEVBR132 as primers; it was performed according to the conditions described above except for the annealing temperature, which was set at 58°C instead of 55°C (36). Gene amplifications with primer pairs HEVBS1695-EV2C and HEVBS1695-HEVBR132 produced two amplicons of about 2,070 and 1,100 bp, respectively.

First-round PCR B assays were performed with the reaction mixtures, including primers 5NC63B and HEVR436 (Table 1). The second-round PCR B assays were done with primers 5NCS663 and HEVR436. The samples were subjected to an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min and then to 41 and 38 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 54°C, and 53°C for 20 s, respectively, for the first- and second-round assays, and extension at 72°C for 20 s. Gene amplification with primer pairs 5NC63B-HEVR436 and 5NC663-HEVR436 produced two amplicons of about 1,200 and 700 bp, respectively.

PCR products were examined on standard 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and were visualized under UV light. Negative (water) and positive (strain CF2660-01, an echovirus 6 strain cultured in MRC5 cells) controls were included in all PCR assays, as from the cDNA synthesis step, and were run in parallel with test samples. Standard precautions were undertaken to avoid the risks of contamination. Visible PCR products after gel electrophoresis were purified and subjected to nucleotide sequencing with the primers P1S1695S and P1R132S (PCR A products; Table 1) and 5NCS663 and HEVR436 (PCR B products), as described elsewhere (36). A contig was assembled with forward and reverse nucleotide sequences for PCR products.

Assay sensitivity.

The sensitivity relative to the results of cell culture infectivity was measured by using a titrated viral culture supernatant from the echovirus 6/CF2660-01 strain. It was serially diluted from 10 to 108 times in a pool of CSF specimens that tested negative for enteroviruses by both diagnostic procedures. Viral RNA of two aliquots of 200 μl of each dilution was extracted with the NucliSens-EasyMag platform. The two eluates of 25 μl were pooled and tested (three replicates) both with the two diagnostic RT-PCR methods (in-house real-time RT-PCR and the NucliSens-EasyQ assays) and with molecular typing assays. The diagnostic RT-PCR assays yielded a positive signal down to dilution 10−6, indicating a detection limit of a 0.05 50% tissue culture infective dose per 5 μl of RNA extract. The limits of detection of genotyping assays were 0.8 and 0.08 50% tissue culture infective doses per 8 μl of RNA extract with the PCR A (VP1 sequence) and B (VP4/VP2 sequences) assays, respectively.

Nucleotide sequence and phylogenetic analyses.

The nucleotide sequence obtained for PCR A and PCR B products were analyzed according to a previously described method (36). Briefly, identification was carried out by comparative analysis of contig sequences with a local database constructed with all of the enterovirus sequences available in GenBank. Analysis was performed by the BLAST method (2), and each sample was assigned the serotype of the strain that gave the highest identity score (45). The result was confirmed by phylogenetic analysis. The sequences representing the VP1 and VP4/partial VP2 capsid proteins were selected from contigs and compared to one another and with the homologous sequences of all of the prototype strains included in the HEV-B species. Multiple sequence alignments were constructed and edited by using the CLUSTAL W (65) and Genedoc (Nicholas and Nicholas Jr available at http://www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc/) computer programs, respectively. MEGA version 3 was used for phylogenetic analysis (28). Genetic distances were calculated by Tamura Nei's model of evolution (63), and the phylogenetic trees were constructed with the neighbor-joining method. The reliability of the branching patterns was determined by the bootstrap resampling test with 1,000 replicates (18).

RESULTS

Retrospective enterovirus genotyping in 45 patients hospitalized in 2005.

Direct enterovirus genotyping was first evaluated retrospectively in 45 inpatients with enterovirus meningitis that were hospitalized in 2005 (Table 2). Amplification of the VP1 sequence with the seminested PCR A assay was carried out directly from stored nucleic acids extracted from CSF specimens and achieved in 42 samples (93.3%). Analysis of nucleotide sequences determined from PCR A products by a gapped BLAST assigned viruses present in the samples to eight different serotypes. Each sample was assigned the type that gave the highest VP1 identity score and, as expected from the specificity of subgeneric primers, all of the serotypes were included within the HEV-B species (Table 2). Echovirus 30 was the most frequently identified serotype, accounting for 66.6% (28 of 42) of the samples tested, followed by echovirus 18, coxsackievirus B5 and B3 (7.1% each [3 of 42]), and echovirus 13 (4.7% [2 of 42]). The viruses detected in three samples were assigned to the echovirus 9, 11, and 33 enterovirus serotypes.

TABLE 2.

Retrospective enterovirus genotyping of 45 CSF specimens obtained in patients with meningitis in 2005

| CSF sample tested | Highest scoring strain

|

Accession no. (CSF)c | Virus isolated

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accession no. | Designation | % nt sequence identitya | Typeb | Designation | Type | ||

| 159064-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 93 (988) | E30 | AM710995 | CF160077-05 | E30 |

| 175081-05 | AY695108 | Zhejiang | 98 (849) | CB5 | AM710996 | CF175089-05 | CB5 |

| 181054-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (854) | E30 | AM710997 | ||

| 185099-05 | DQ936620 | 304037 | 93 (854) | CB3 | AM710998 | CF185104-05 | CB3 |

| 192020-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 96 (856) | E30 | AM710999 | ||

| 192022-05 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 97 (835) | E13 | AM711000 | CF193056-05 | E13 |

| 194070-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (855) | E30 | AM711001 | CF196050-05 | E30 |

| 196046-05 | DQ092796 | Human E11 | 96 (955) | E11 | AM711002 | CF196051-05 | E11 |

| 197025-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 96 (855) | E30 | AM711003 | CF197006-05 | E30 |

| 199006-05e | DQ345771 | Constant | 86 (388) | E6 | AM696266 | ||

| 203029-05 | DQ936620 | 304037 | 93 (851) | CB3 | AM711004 | CF203101-05 | CB3 |

| 204013-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 93 (981) | E30 | AM711005 | ||

| 206006-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 93 (992) | E30 | AM711006 | ||

| 206007-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 93 (986) | E30 | AM711007 | ||

| 207049-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (854) | E30 | AM711008 | ||

| 216056-05 | AJ537606 | CF1393-00 | 97 (841) | E13 | AM711009 | CF216077-05 | E13 |

| 218022-05 | AY695108 | Zhejiang 12/02 | 97 (852) | CB5 | AM711010 | ||

| 220018-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 95 (855) | E30 | AM711011 | CF220062-05 | E30 |

| 230016-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (855) | E30 | AM711012 | CF230033-05 | E30 |

| 232001-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 96 (855) | E30 | AM711013 | CF232022-05 | E30 |

| 234024-05 | AY167774 | WK-18-04-00 | 90 (837) | E33 | AM711014 | CF235069-05 | E33 |

| 235066-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 93 (975) | E30 | AM711015 | CF237031-05 | E30 |

| 236023-05 | AY695108 | Zhejiang | 97 (849) | CB5 | AM711016 | CF238048-05 | CB5 |

| 241017-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (857) | E30 | AM711017 | ||

| 242044-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 92 (986) | E30 | AM711018 | ||

| 257023-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (855) | E30 | AM711019 | ||

| 258066-05 | AF524867 | DM | 95 (928) | E9 | AM711020 | ||

| 264080-05 | AB188509 | 80365/Hiroshima | 94 (767) | E18 | AM711021 | CF265112-05 | E18 |

| 265024-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (855) | E30 | AM711022 | CF265113-05 | E30 |

| 265094-05 | No amplification | ||||||

| 272012-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (855) | E30 | AM711023 | CF272058-05 | E30 |

| 278024-05 | AB167999 | 03-3003FCR2 | 98 (724) | E18 | AM711024 | CF279084-05 | E18 |

| 283003-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (855) | E30 | AM711025 | ||

| 298098-05 | DQ093621 | 302784 | 94 (853) | CB3 | AM711026 | ||

| 302018-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (854) | E30 | AM711027 | CF302019-05 | E30 |

| 302022-05 | AB188509 | Hiroshima-JP-04 | 94 (767) | E18 | AM711028 | ||

| 302024-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (855) | E30 | AM711029 | ||

| 304075-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 92 (986) | E30 | AM711030 | CF306033-05 | E30 |

| 308026-05 | AJ314833 | sh/Roma99 | 92 (307) | CA9 | AM696267 | ||

| 312098-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 95 (850) | E30 | AM711031 | CF313076-05 | E30 |

| 313072-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 97 (854) | E30 | AM711032 | ||

| 316003-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 92 (977) | E30 | AM711033 | ||

| 344017-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 97 (856) | E30 | AM711034 | ||

| 346022-05 | AJ417361 | 00CF1532/P17 | 97 (855) | E30 | AM711035 | ||

| 350034-05 | AJ295172 | ITA97-002 | 92 (991) | E30 | AM711036 | CF350107-05 | E30 |

nt, nucleotide. Numbers in parentheses indicate the length of the nucleotide sequence investigated by BLAST analysis.

E, echovirus; CB, coxsackievirus B; CA, coxsackievirus A.

That is, the accession number of the nucleotide sequence determined in the CSF specimens tested.

That is, the corresponding virus isolates recovered in peripheral specimens, genotyped prospectively in 2005 (36).

BLAST searches with VP4-VP2 sequences are indicated in boldface.

A PCR B assay directed at the 5′ part of the enterovirus genome (amplification of complete VP4 and partial VP2 encoding sequences) was performed in three samples for which PCR A assay did not detect any viral genomic sequence. Amplification was achieved in two specimens, which were assigned the echovirus 6 (199006-05) and coxsackievirus A9 (308026-05) enterovirus serotypes. In the third specimen (265094-05), no amplification product was detected, suggesting an amount of viral RNA below the detection limit, mispairing of any of the different oligonucleotides, or RNA degradation during storage. Altogether, using PCR A and PCR B assays, enterovirus genotyping was achieved directly in CSF samples in 44 of 45 patients studied (97.8%).

General characteristics of patients included in the prospective study.

In 2006, 61 patients received a clinical diagnosis of enterovirus meningitis and were included in the study for the prospective identification of the enterovirus involved either directly in CSF specimens (n = 54) or indirectly after isolation in cell culture (n = 31). There were 20 adults (32.8%) and 41 children (67.2%); the median patient age was 7.7 years (age range, 2 days to 71 years). The male/female ratios were 1.5:1 and 1.7:1 in adults and children, respectively. The seasonal distribution of enterovirus meningitis in 2006 showed that 54% of cases occurred in July (n = 22) and August (n = 11), with further cases being recorded up to December 2006 (data not shown).

Prospective enterovirus genotyping with CSF.

Direct genotyping in CSF samples was prospectively performed in 54 consecutive patients with enterovirus meningitis in 2006 with the viral RNA used for the diagnostic RT-PCR assay. An amplicon was successfully obtained with the PCR A assay in 42 (77.8%) samples, and all of the VP1 sequences were determined. The highest VP1 identity scores determined by the gapped BLAST analysis are presented in Table 3. The nucleotide identity values ranged from 83 to 97%, and most of the sequences (28 of 42) displayed at least 90% nucleotide similarity with an enterovirus sequence in the database. A nucleotide similarity value lower than 90% was observed for 14 sequences, 9 of which had the highest VP1 identity score with the same echovirus 6 strain (AY896760) isolated in Russia in 1999 (27). The other five sequences displayed highest identity scores with sequences assigned to the serotypes coxsackievirus B1 and B2 and echovirus 9 (n = 2) and 21.

In 12 CSF samples, no amplification was obtained with the PCR A assay, and the alternative PCR B assay was used to detect the viral genome. The expected amplification product was not obtained in only one sample (045067-06), which suggests an extremely low viral load in the P1 patient. In seven CSF samples, the analysis of the nucleotide sequence determined assigned the enteroviruses to only three serotypes: echovirus 6 (n = 5), echovirus 25 (n = 1), and enterovirus 71 (n = 1), which belongs to the HEV-A species. With four samples, the identification was not straightforward. For samples 200001-06, 205064-06, and 312082-06 (patients P25, P28, and P55, respectively), the highest scoring strain (AY875692) was reported as coxsackievirus B5 in the database, while the second and third highest scoring strains were reported as echovirus 25. When BLAST analysis was done with a selected segment corresponding to the only VP4-VP2 sequence, the first two samples (200001-06 and 205064-06) were assigned to serotype echovirus 25 (AB239987). With the third CSF sample (312082-06), the highest scoring strain (DQ251322) detected in the database had been reported as an untyped strain, while the second highest scoring strain (AB239987) had been identified as an echovirus 25. In addition, identification based on the VP1 sequence of the virus isolate obtained from a throat swab paired with the CSF sample assigned the virus to the echovirus 25 serotype (see Table 3). Finally, with the 237015-06 sample (patient P45), the highest scoring strain (AY896765) determined by genotyping had been reported as an echovirus 7, but all of the first four highest scoring strains had a different serotype, which makes it impossible to unequivocally identify the virus.

Overall, direct genotyping with both assays (PCR A and PCR B) allowed the identification of the involved enterovirus in 52 (96.3%) of the 54 consecutive patients with a positive diagnosis of meningitis. Thirteen different serotypes were within the HEV-B species, and one serotype was within the HEV-A species.

Prospective genotyping of enterovirus isolates.

Genotyping was also performed with isolates recovered in 31 of 61 inpatients with enterovirus meningitis, including 24 inpatients with paired CSF samples. All of the enterovirus isolates were genotyped with either the PCR A assay (n = 30) or the PCR B assay (n = 1). The nucleotide identity values determined by a gapped BLAST analysis (Table 3) ranged from 82 to 97%, and most (19 of 31) were greater than 90%. No discordance was observed between the serotype identified with the CSF specimens and that determined with the isolates recovered from throat swabs or feces. Moreover, the PCR A-positive CSF samples and the virus strains from paired specimens were assigned the same highest scoring strains. In four patients in whom genotyping was determined with the VP4-VP2 sequence detected directly in CSF samples, the results were also confirmed by genotyping with the VP1 sequence in paired virus isolates. Ten different serotypes were identified within the HEV-B species (PCR A assay), and one serotype was identified within the HEV-A species (PCR B assay) (Table 3).

Overall, enterovirus genotyping with CSF specimens and enterovirus isolates allowed the identification of the virus strain involved in 59 of 61 (96.7%) patients (Table 4). Echovirus 13 and echovirus 6 were responsible for a meningitis syndrome in 24.6% (15 of 61) and 23% (14 of 61) of the patients, respectively. They were followed by coxsackievirus B5 (7 of 61 [11.5%]); echovirus 18 and 25 (each 4 of 61 [6.6%]); coxsackievirus B4 (3 of 61 [4.9%]); and echovirus 9 and 30, coxsackievirus B2, and enterovirus 71 (each 2 of 71 [3.3%]). Serotypes coxsackievirus B1 and B3 and echovirus 21 and 27 were each identified once. The causative enteroviruses remained unidentified in two patients (P1 and P45).

TABLE 4.

Number of enterovirus serotypes identified in patients with meningitis in 2006 through direct (CSF samples) and indirect (virus isolates) genotyping

| Identified serotype | No. (%)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CSF samples (n = 54) | Virus isolates (n = 31) | Total meningitis cases (n = 61) | |

| Echovirus 13 | 13 (24.1) | 8 (25.8) | 15 (24.6) |

| Echovirus 6 | 14 (25.9) | 7 (22.6) | 14 (23) |

| Coxsackievirus B5 | 5 (9.3) | 4 (12.9) | 7 (11.5) |

| Echovirus 25 | 4 (7.4) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (6.6) |

| Echovirus 18 | 3 (5.6) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (6.6) |

| Echovirus 30 | 2 (3.7) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (3.3) |

| Coxsackievirus B2 | 2 (3.7) | 0 | 2 (3.3) |

| Coxsackievirus B4 | 2 (3.7) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (4.9) |

| Echovirus 9 | 2 (3.7) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (3.3) |

| Echovirus 27 | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (1.6) |

| Echovirus 21 | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (1.6) |

| Coxsackievirus B1 | 1 (1.9) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.6) |

| Coxsackievirus B3 | 1 (1.9) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.6) |

| Enterovirus 71 | 1 (1.9) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (3.3) |

| Unidentified | 2 (3.7) | 0 | 2 (3.3) |

n, Total number.

Prospective enterovirus genotyping in patients with other clinical syndromes.

In the prospective study, an enterovirus isolate was genotyped in four inpatients admitted with clinical manifestations other than those associated with meningitis. Echovirus 6 and 13 were identified in two patients presenting with diarrhea. Another echovirus 6 was isolated from a bronchoalveolar fluid specimen in an immunocompromised 71-year-old woman who died during hospitalization. Finally, enterovirus 71 was isolated in the throat of a healthy 1-year-old boy. His brother (patient P33) was included in the study with proven enterovirus meningitis, and enterovirus 71 was identified directly from the CSF sample.

Phylogenetic confirmation of genotyping results obtained with the BLAST analysis.

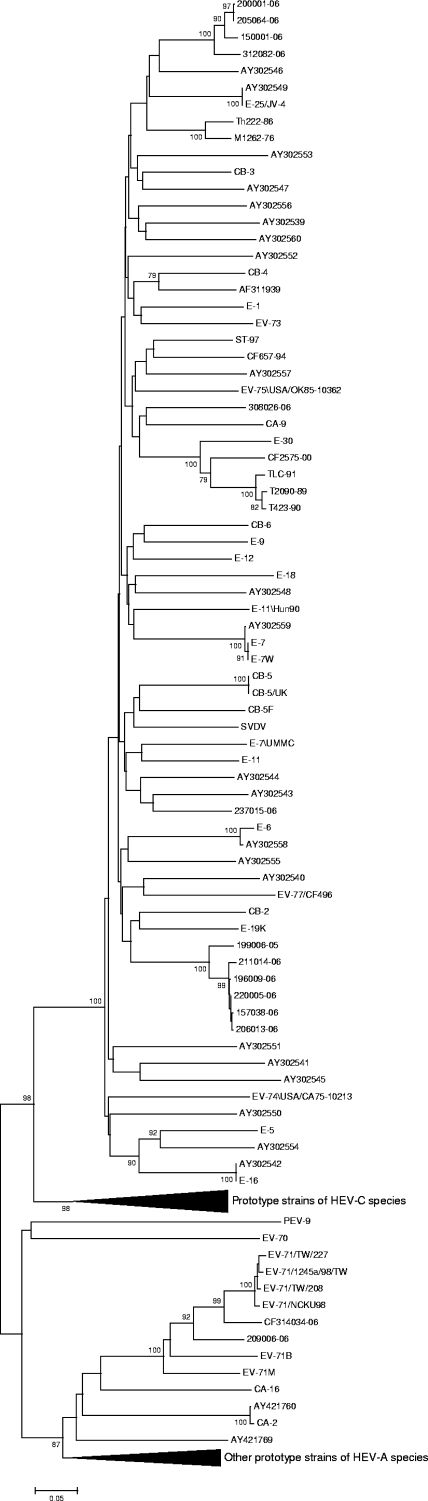

Phylogenetic analysis was performed with the 14 VP4/VP2 sequences (obtained from 13 CSF specimens and 1 isolate) with homologous sequences of all prototype strains to confirm the typing results. In the VP4-VP2 phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), samples that were assigned the same serotype clustered together but not with their homologous prototype strain. Sequences in four samples (150001-06, 200001-06, 205064-06, and 312082-06) clustered with a 100% bootstrap value in accordance with their clustering observed in the VP1 sequence. Thus, according to the BLAST results, they should be considered as echovirus 25. The virus in one patient (237015-06) which could not be formally identified by the BLAST comparison clustered with the echovirus 17 prototype strain but with a bootstrap value lower than 70%. Phylogenetic analysis performed with the VP4 coding segment alone did not provide additional information (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on the complete VP4 and partial VP2 encoding sequences (420 nucleotides) of enteroviruses obtained from CSF specimens and isolates and all HEV prototype strains. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method and validated with 1,000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates. Only bootstrap values of greater than 70% are shown. Genetic distances were calculated with Tamura-Nei's model of evolution, and branch length is drawn to the indicated scale (proportion of nucleotide substitutions per site).

The 114 VP1 sequences (obtained from 84 CSF specimens and 30 isolates) were also compared to homologous sequences of all prototype strains (data not shown). Sequences that were assigned the same serotype by the BLAST analysis were all monophyletic with respect to the homologous prototype sequence in the phylogenetic tree. All of the genetic clusters corresponding to each serotype had a 100% bootstrap value, and therefore the phylogenetic analysis definitely confirmed genotyping with the VP1 sequences. Moreover, whenever the number of sequences made it possible, phylogenetic analysis evidenced reliable subclusterings. For instance, within the echovirus 6, coxsackievirus B5, and echovirus 18 serotypes, two or three distinct lineages were observed (data not shown). In contrast, within the cluster of the echovirus 13 serotype, all of the strains displayed little genetic diversity.

DISCUSSION

In particularly serious or atypical presentations of CNS infections or in the event of an epidemic of meningitis, identifying the causative agent rapidly is of practical importance because a number of different viruses can be involved (24). Since enteroviruses are the most commonly identifiable cause of aseptic meningitis (50), it would be an advantage if enterovirus identification could be achieved prospectively, directly within CSF, through rapid genotyping: the overall management of outbreaks would be improved (40).

Direct enterovirus genotyping in 99 patients with meningitis using a two-step method.

The two-step method described here was used in 99 patients with positive diagnosis of enterovirus meningitis, including 54 sequential patients enrolled in 2006 for the prospective study and 45 patients with a positive diagnosis of enterovirus meningitis made in 2005 (36) for the retrospective study. The enterovirus serotype was identified directly in CSF samples in 84 of 99 patients (84.8%) with the first assay (PCR A; VP1 sequence). In the 15 patients for whom serotype identification was not achieved, genotyping was done successfully in 12 with the second assay (PCR B; VP4/VP2 sequence). Overall, direct genotyping was achieved in 97% of the patients in the present study.

Long nucleotide segments are not readily amplified by consensus PCR, and the amplicon length may explain the insufficient sensitivity of PCR A assay. With a two-step approach, Thoelen et al. (64) achieved direct enterovirus identification in 65% of 122 patients using degenerate primers designed for amplifying and sequencing a VP1 segment smaller than in the present study. A second step with multiple serotype-specific primers was necessary for identifying enterovirus strains in 35% of the patients. Few other PCR assays have been developed to identify enterovirus serotype directly in CSF specimens (13, 23, 42, 64). The methods were based on sequencing of different partial VP1 segments after nested gene amplification and used either generic (13, 42) or species-specific (23, 64) primers. To our knowledge, none have been used prospectively in a clinical diagnostic laboratory to identify enteroviruses responsible for meningitis and other CNS diseases.

In our study, when low amounts of viral RNA in CSF specimens prevented genotyping with the VP1 sequence, identification with the VP4/VP2 sequence was used as an alternative method, because of the simplicity of the amplification/sequencing stages, which are performed with only three primers, and its greater sensitivity. Using a two-step approach, Manzara et al. (34) showed that typing with the VP4/VP2 sequence was helpful, provided that amino acid sequence identity was not less than 90% with the highest scoring strain obtained by BLAST analysis. However, concerning the validity of enterovirus typing with the VP4/VP2 sequence, opinions are highly divergent. While the VP4 sequence was effective in identifying enterovirus serotypes (22), the 5′ part of the VP2 encoding sequence was reported not to be efficient at distinguishing between all enterovirus serotypes (13, 22, 44). In our experience, the interpretation of BLAST analyses of raw contigs that included a portion of the 5′ untranslated region and the VP4/VP2 segment posed problems in some patients. However, when the portions corresponding to the 5′ untranslated region were deleted from the contigs, identification was straightforward, and all of the viruses were assigned the echovirus 25 serotype. Overall, the BLAST analysis of the VP4/VP2 segment identified four serotypes (echovirus 6, 7, and 25 and coxsackievirus A9) within the HEV-B species and one serotype (enterovirus 71) within the HEV-A species. Although phylogenetic analysis of all of the VP1 sequences validated genotyping results obtained with BLAST comparisons, it was of little help in validating genotyping results obtained with the VP4/VP2 sequences. In contrast to the results obtained with the VP1 sequences, clustering with homologous prototype sequences was not observed with the VP4/VP2 sequences, with the exception of those assigned to the enterovirus 71 serotype. This is consistent with previous observations which indicated that this genome segment might not be appropriate for identifying all enteroviruses (13, 44). However, homotypic sequences clustered together with high bootstrap values, suggesting that this segment is suitable for detecting reliable phylogenetic relationships between circulating enteroviruses.

Direct genotyping versus indirect genotyping: implications for enterovirus epidemiology.

In the prospective study in 2006, a virus isolate was recovered in 31 of 61 patients (50.8%) with positive diagnosis of enterovirus meningitis, including seven patients for whom direct genotyping was not possible. Thus, an enterovirus was identified either with the direct or indirect method for 96.7% of the patients included. Although the overall frequencies of the most frequent serotypes were similar with both methods, three minor serotypes (coxsackievirus B2 and echovirus 21 and 27) were detected only by direct genotyping because no specimen was available for cell culture (Table 3). In 2005, an enterovirus isolate was obtained in only 41 of the 70 (58.5%) patients with meningitis. The retrospective analysis of 45 CSF specimens collected in 2005 allowed the identification of the involved enterovirus in 19 additional patients (for whom no enterovirus isolate was obtained; Table 2) and the detection of two additional serotypes (echovirus 6 and coxsackievirus A9), extending the results of indirect genotyping reported earlier (36). Since only CSF samples are provided for patients with meningitis, direct molecular typing allowed a more accurate and complete picture of the circulation patterns of involved enteroviruses in both prospective and retrospective studies.

During the prospective study, enterovirus meningitis was diagnosed in 61 inpatients and 14 distinct serotypes were identified (see Table 4). In 2005, by comparison, meningitis was evidenced in 70 inpatients, and 10 serotypes were identified (36). Although the numbers of patients and enterovirus serotypes were closely similar in the 2 years, the epidemiological patterns of EV serotypes determined were very different. Among the enterovirus strains identified in patients hospitalized in 2005, the most common serotype, echovirus 30, was replaced in 2006 by the echovirus 13 and 6 serotypes. This is not unexpected since these two serotypes were among the three serotypes most frequently isolated between 2000 and 2004 in France (54). The high immunization rate of the general population against echovirus 30 acquired during earlier meningitis outbreaks (2000 and 2005) may explain the provisional extinction of this serotype in France. However, in 2006, in Spain, echovirus 30 was the most frequently isolated serotype involved in meningitis (21). The coxsackievirus B5 serotype was the third most identified serotype both in 2005 and in 2006, accounting for 11.5% of the meningitis cases in the prospective study. This virus has been regularly isolated in France since 2000 and in 2003 was the most frequently isolated serotype (54). It was also the most frequently isolated serotype in Korea in 2005 (29). It has been suggested that the cyclic occurrence of coxsackievirus B5 infections is due to the reemergence of specific genotypes (27). This may explain the persistence of the serotype in the general population within the Clermont-Ferrand area. The pattern of enterovirus serotypes responsible for meningitis in 2006 in Clermont-Ferrand was also marked by the detection of enterovirus 71 in two patients. This is an unexpected finding because the virus was rarely detected in acute diseases during the period from 2000 to 2004 (54). According to a recent study in Norway, the prevalence of this enterovirus was 6.8% in a cohort of 113 asymptomatic children (69). This finding suggests that the circulation of enterovirus 71 might also be underestimated in France, and detection of this serotype in the present study underlines the necessity of molecular typing for enterovirus serotypes within the HEV-A species, because enterovirus 71 can be associated with severe brain stem encephalitis and pulmonary edema (68).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the feasibility of direct genotyping in CSF for prospective and rapid identification of enteroviruses involved in meningitis and provides a more complete picture of the circulation patterns of enteroviruses than indirect genotyping. Among the factors that can be involved in the varied pattern of CNS diseases caused by enteroviruses, differences in the enterovirus susceptibility of individuals and populations have been suggested, as have factors intrinsic to the virus itself. Analysis of CSF during acute and persistent infection phases could provide an insight into the pathogenesis of CNS infection by combining rapid procedures for clinical diagnosis, direct genotyping and, in the future, quantitative detection of enteroviruses.

Acknowledgments

Our laboratory (EA3843) is supported by grants from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche, et de la Technologie.

We acknowledge the contributions of the technical staff of the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand in the diagnosis of enterovirus infections and the original isolation of virus strains. We also appreciate the technical contribution of Isabelle Simon and Marielle Jarsaillon for meticulous and helpful assistance in virus culture and sequencing, and we thank Jeffrey Watts for his revision of the English manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agol, V. I. 1997. Recombination and other rearrangements in picornaviruses. Semin. Virol. 877-84. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Meyers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Med. Biol. 215403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 2006. Poliosurveillance report, January-December 2005, p. 1-4. Polio lab network quarterly update, vol. 12. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archimbaud, C., A. Mirand, M. Chambon, C. Regagnon, J.-L. Bailly, H. Peigue-Lafeuille, and C. Henquell. 2004. Improved diagnosis on a daily basis of enterovirus meningitis using a one-step real-time RT-PCR assay. J. Med. Virol. 74604-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archimbaud, C., J.-L. Bailly, M. Chambon, O. Tournilhac, P. Travade, and H. Peigue-Lafeuille. 2003. Molecular evidence of persistent echovirus 13 meningoencephalitis in a patient with relapsed lymphoma after an outbreak of meningitis in 2000. J. Clin. Microbiol. 414605-4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailly, J.-L., A. Beguet, M. Chambon, C. Henquell, and H. Peigue-Lafeuille. 2000. Nosocomial transmission of echovirus 30: molecular evidence by phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 encoding sequence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 382889-2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailly, J.-L., M. Chambon, C. Henquell, J. Icart, and H. Peigue-Lafeuille. 2000. Genomic variations in echovirus 30 persistent isolates recovered from a chronically infected immunodeficient child and comparison with the reference strain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38552-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailly, J.-L., D. Brosson, C. Archimbaud, M. Chambon, C. Henquell, and H. Peigue-Lafeuille. 2002. Genetic diversity of echovirus 30 during a meningitis outbreak, demonstrated by direct molecular typing from cerebrospinal fluid. J. Med. Virol. 68558-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailly, J.-L., M.-C. Cardoso, A. Labbe, and H. Peigue-Lafeuille. 2004. Isolation and identification of an enterovirus 77 recovered from a refugee child from Kosovo, and characterization of the complete virus genome. Virus Res. 99147-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown, B. A., M. S. Oberste, J. P. Alexander, M. L. Kennett, and M. A. Pallansh. 1999. Molecular epidemiology and evolution of enterovirus 71 strains isolated from 1970 to 1998. J. Virol. 739969-9975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown, B., M. S. Oberste, K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 2003. Complete genomic sequencing shows that polioviruses and members of human enterovirus species C are closely related in the noncapsid region. J. Virol. 778973-8984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caro, V., S. Guillot, F. Delpeyroux, and R. Crainic. 2001. Molecular strategy for “serotyping” of human enteroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 8279-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casas, I., G. F. Palacios, G. Trallero, D. Cisterna, M. C. Freire, and A. Tenorio. 2001. Molecular characterization of human enteroviruses in clinical samples: comparison between VP2, VP1, and RNA polymerase regions using RT nested PCR assays and direct sequencing of products. J. Med. Virol. 65138-148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Echovirus type 13: United States. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50777-780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Outbreaks of aseptic meningitis associated with echovirus 9 and 30 and preliminary reports on enterovirus activity. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52761-764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang, L. Y., L. M. Huang, S. S. F. Gau, Y. Y. Wu, S. H. Hsia, T. Y. Fan, K. L. Lin, Y. C. Huang, C. Y. Lu, and T. Y. Lin. 2007. Neurodevelopment and cognition in children after enterovirus 71 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 3561226-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chevaliez, S., A. Szendroi, V. Caro, J. Balanant, S. Guillot, G. Berencsi, and F. Delpeyroux. 2004. Molecular comparison of echovirus 11 strains circulating in Europe during an epidemic of multisystem hemorrhagic disease of infants indicates that evolution generally occurs by recombination. Virology 32556-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies, an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 4363-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginocchio, C., F. Zhang, A. Malhotra, R. Manji, P. Sillekens, H. Folen, H. M. Overdyk, and M. Peeters. 2005. Development, technical performance, and clinical evaluation of a NucliSens basic kit application for detection of enteroviruses RNA in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 432616-2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaser, C. A., S. Honarmand, L. J. Anderson, D. P. Schnurr, B. Forghani, F. L. Schuster, L. J. Christie, and J. H. Tureen. 2006. Beyond viruses: clinical profiles and etiologies associated with encephalitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 431565-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guttierez Rodrigues, M. A., L. Garcia Comas, I. Rodero Garduno, C. Garcia Fernandez, M. Ordobas Gavin, and R. Ramirez Fernandez. 2006. Increase in viral meningitis cases reported in the autonomous region of Madrid, Spain, 2006. Eur. Surveill. 11E061103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishiko, H., Y. Shimada., M. Yonaha, O. Hashimoto, A. Hayashi, K. Sakae, and N. Takeda. 2002. Molecular diagnosis of human enteroviruses by phylogeny-based classification by use of the VP4 sequence. J. Infect. Dis. 185744-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itturiza-Gomara, M., B. Megson, and J. Gray. 2006. Molecular detection and characterization of human enteroviruses directly from clinical samples using RT-PCR and DNA sequencing. J. Med. Virol. 75243-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Julian, K. G., J. A. Mullins, A. Olin, H. Peters, W. A. Nix, M. S. Oberste, J. C. Lovchik, A. Bergmann, R. J. Brechner, R. A. Myers, A. A. Marfin, and G. L. Campbell. 2003. Aseptic meningitis epidemic during a West Nile virus avian epizootic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 91082-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khetsuriani, N., A. LaMonte-Fowlkes, M. S. Oberste, and M. A. Pallansch. 2006. Enterovirus surveillance-United States, 1970-2005. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55(SS-8)1-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirschke, D. L., T. F. Jones, S. C. Buckingham, A. S. Craig, and W. Schaffner. 2002. Outbreak of aseptic meningitis associated with echovirus 13. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 211034-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopecka, H., B. Brown, and M. A. Pallansch. 1995. Genotypic variation in coxsackievirus B5 isolates from three different outbreaks in the United States. Virus Res. 38125-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetic analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, S. T., C. S. Ki, and N. Y. Lee. 2007. Molecular characterization of enteroviruses isolated from patients with aseptic meningitis in Korea, 2005. Arch. Virol. 152963-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindberg, A. M., P. Andersson, C. Savolainen, M. N. Mulders, and T. Hovi. 2003. Evolution of the genome of human enterovirus B: incongruence between phylogenies of the VP1 and 3CD regions indicates frequent recombination within the species. J. Gen. Virol. 841223-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukashev, A. N., V. A. Lashkevich, O. E. Ivanova, G. A. Koroleva, A. E. Hinkkanen, and J. Ilonen. 2003. Recombination in circulating enteroviruses. J. Virol. 7710423-10431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukashev, A. N., V. A. Lashkevich, G. A. Koroleva, J. Ilonen, and A. E. Hinkkanen. 2004. Recombination in uveitis-causing enterovirus strains. J. Gen. Virol. 85463-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukashev, A. N., V. A. Lashkevich, O. E. Ivanova, G. A. Koroleva, A. E., Hinkkanen, and J. Ilonen. 2005. Recombination in circulating Human enterovirus B: independent evolution of structural and nonstructural genome regions. J. Gen. Virol. 863281-3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manzara, S., M. Custillo, G. La Rosa, C. Marianelli, P. Cattani, and G. Fadda. 2002. Molecular identification and typing of enteroviruses isolated from clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 404554-4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melnick, J. L. 1996. Enteroviruses: polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses, p. 655-712. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, R. M. Channock., J. L. Melnick, T. P. Monath, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, PA.

- 36.Mirand, A., C. Archimbaud, C. Henquell, Y. Michel, M. Chambon, H. Peigue-Lafeuille, and J.-L. Bailly. 2006. Prospective identification of HEV-B enteroviruses during the 2005 outbreak. J. Med. Virol. 781624-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mirand, A., C. Henquell, C. Archimbaud, H. Peigue-Lafeuille, and J.-L. Bailly. 2007. Emergence of echovirus 30 lineages is marked by serial genetic recombination events. J. Gen. Virol. 88166-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Modlin, J. F. 1997. Update on enterovirus infections in infants and children. Adv. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 12155-180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Modlin, J. F. 2000. Coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses, p. 1904-1919. In G. L Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and E. Dolin (ed.), Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY.

- 40.Muir, P., U. Kämmerer, K. Korn, M. N. Mulders, T. Pöyry, B. Weissbrich, R. Kandolf, G. M. Cleator, A. M. van Loon, et al. 1998. Molecular typing of enteroviruses: current status and future requirements. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11202-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulders, M. N., M. Salminen, N. Kalkkinen, and T. Hovi. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of coxsackievirus B4 and disclosure of the correct VP1/2Apro cleavage site: evidence for high genomic diversity and long-term endemicity of distinct genotypes. J. Gen. Virol. 81803-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nix, W. A., M. S. Oberste, and M. A. Pallansch. 2006. Sensitive, seminested PCR amplification of VP1 sequences for direct identification of all enterovirus serotypes from original clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 442698-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norder, H., L. Bjerregaard, and L. O. Magnius. 2001. Homotypic echoviruses share amino-terminal VP1 sequence homology applicable for typing. J. Med. Virol. 6335-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 1998. Molecular phylogeny of all human enterovirus serotypes based on comparison of sequences at the 5′ end of the region encoding VP2. Virus Res. 5835-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, D. R. Kilpatrick, M. R. Flemister, B. A. Brown, and M. A. Pallansch. 1999. Typing of human enteroviruses by partial sequencing of VP1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 371288-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 2004. Evidence for frequent recombination within species human enterovirus B based on complete genomic sequences of all thirty-seven serotypes. J. Virol. 78855-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oberste, M. S., S. Penaranda, K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 2004. Complete genome sequences of all members of the species Human enterovirus A. J. Gen. Virol. 851597-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oprisan, G., M. Combiescu, S. Guillot, V. Caro, A. Combiescu, F. Delpeyroux, and R. Crainic. 2002. Natural genetic recombination between co-circulating heterotypic enteroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 832193-2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palacios, G., I. Casas, A. Tenorio, and C. Freire. 2002. Molecular identification of enterovirus by analyzing a partial VP1 genomic region with different methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40182-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pallansch, M. A., and R. Roos. 2006. Enteroviruses: polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses, p. 839-893. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott/The Williams & Wilkins Co., Philadelphia, PA.

- 51.Peigue-Lafeuille, H., C. Archimbaud, A. Mirand, M. Chambon, C. Regagnon, H. Laurichesse, P. Clavelou, A. Labbé, J. L. Bailly, and C. Henquell. 2006. From prospective molecular diagnosis of enterovirus meningitis … to prevention of antibiotic resistance. Med. Mal. Infect. 36124-131. (In French.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pöyry, T., L. Kinnunen, T. Hyypiä, B. Brown, C. Horsnell, T. Hovi, and G. Stanway. 1996. Genetic and phylogenetic clustering of enteroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 771699-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Read, S. J., K. J. M. Jeffery, and C. R. M. Bangham. 1997. Aseptic meningitis and encephalitis: the role of PCR in the diagnostic laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35691-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Réseau de Surveillance des Entérovirus. 2005. Bilan de l'activité au cours de l'année, p. 1-6. Institut de Veille Sanitaire, Saint-Maurice, France.

- 55.Rezig, D., A. Ben Yahia, H. Ben Abdallah, O. Bahri, and H. Triki. 2004. Molecular characterization of coxsackievirus B5 isolates. J. Med. Virol. 72268-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rotbart, H. A., M. H. Sawyer, S. Fast, C. Lewinski, N. Murphy, E. F. Keyser, J. Spadora, S. Y. Kao, and M. Loeffelholz. 1994. Diagnosis of enteroviral meningitis using PCR with a microwell detection assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 322590-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rotbart, H. A. 1995. Enteroviral infections of the central nervous system. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20971-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Santti, J., T. Hyypiä, L. Kinnunen, and M. Salminen. 1999. Evidence of recombination among enteroviruses. J. Virol. 738741-8749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santti, J., H. Harvala, L. Kinnunnen, and T. Hyypia. 2000. Molecular epidemiology and evolution of coxsackievirus A9. J. Gen. Virol. 811361-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Savolainen, C., T. Hovi, and M. N. Mulders. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of echovirus 30 in Europe: succession of dominant sublineages within a single major genotype. Arch. Virol. 146521-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simmonds, P., and J. Welch. 2006. Frequency and dynamics of recombination within different species of human enteroviruses. J. Virol. 80483-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stanway, G., F. Brown, P. Christian, T. Hovi, T. Hyypiä, A. M. Q. King, N. J. Knowles, S. M. Lemon, P. D. Minor, M. A. Pallansch, A. C. Palmemberg, and T. Skern. 2005. Family Picornaviridae, p. 757-778. In C. M. Fauquet, M. A. Mayo, J. Maniloff, U. Desselberger, and L. A. Ball (ed.), Virus taxonomy: eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier/Academic Press, London, England.

- 63.Tamura, K., and M. Nei. 1993. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10512-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thoelen, I., P. Lemey, I. Van der Donck, K. Beuselink, A. M. Lindberg, and M. Van Ranst. 2003. Molecular typing and epidemiology of enteroviruses identified from an outbreak of aseptic meningitis in Belgium in the summer of 2000. J. Med. Virol. 70420-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 254876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vuorinen, T., R. Vanionpaa, and T. Hyypiä. 2003. Five years' experience of reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction in daily diagnosis of enterovirus and rhinovirus infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37452-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang, J. R., H. P. Tsai, S. W. Huang, P. H. Kuo, D. Kiang, and C. C. Liu. 2002. Laboratory diagnosis and genetic analysis of an echovirus 30-associated outbreak of aseptic meningitis in Taiwan in 2001. J. Clin. Microbiol. 404439-4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang, S. M., H. Y. Lei, K. J. Huang, J. M. Wu, J. R. Wang, C. K. Yu, I. J. Su, and C. C. Liu. 2003. Pathogenesis of enterovirus 71 brainstem encephalitis in pediatric patients: roles of cytokines and cellular immune activation in patients with pulmonary edema. J. Infect. Dis. 188564-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Witsø, E., G. Palacios, O. Cinek, L. C. Stene, B. Grinde, D. Janowitz, W. I. Lipkin, and K. S. Rønningen. 2006. High prevalence of human enterovirus A infections in natural circulation of human enteroviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 444095-4100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]