Abstract

Changes in the interactions between intestinal cells and their surrounding environment during virus infection have not been well documented. The growth and survival of intestinal epithelial cells, the main targets of rotavirus infection, are largely dependent on the interaction of cell surface integrins with the extracellular matrix. In this study, we detected alterations in cellular integrin expression following rotavirus infection, identified the signaling components required, and analyzed the subsequent effects on cell binding to the matrix component collagen. After rotavirus infection of intestinal cells, expression of α2β1 and β2 integrins was up-regulated, whereas that of αVβ3, αVβ5, and α5β1 integrins, if present, was down-regulated. This differential regulation of integrins was reflected at the transcriptional level. It was unrelated to the use of integrins as rotavirus receptors, as both integrin-using and integrin-independent viruses induced integrin regulation. Using pharmacological agents that inhibit kinase activity, integrin regulation was shown to be dependent on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) but independent of the activities of the mitogen-activated protein kinases p38 and ERK1/2, and cyclooxygenase-2. Replication-dependent activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway was observed following infection of intestinal and nonintestinal cell lines. Rotavirus activation of PI3K was important for regulation of α2β1 expression. Blockade of integrin regulation by PI3K inhibition led to decreased adherence of infected intestinal cells to collagen and a concomitant decrease in virus titer. These findings indicate that rotavirus-induced PI3K activation causes regulation of integrin expression in intestinal cells, leading to prolonged adherence of infected cells to collagen and increased virus production.

Rotavirus is a major cause of dehydrating gastroenteritis in infant humans and animals throughout the world. Differentiated epithelial cells on villi in the small intestine (enterocytes) are the main targets of infection, leading to cell death, a reduction in villus epithelium area, loss of absorptive capacity, and osmotic dysregulation (3, 7, 48, 53). Enterocytes are attached to the basement membrane through interactions between the basement matrix and cell-surface adhesion molecules, mainly members of the integrin family (4, 6, 49, 64). Increased enterocyte loss is a feature of rotavirus disease, suggesting that reduced enterocyte adhesion occurs (9). However, the molecules involved in changes in attachment of enterocytes to the matrix during rotavirus infection and how this process relates to viral replication and pathogenesis have not been analyzed.

Integrins provide a means for cells to respond to their environment through intracellular signaling networks controlling crucial cellular processes such as adhesion, proliferation, migration, differentiation, and survival (1, 20, 38, 55, 69). These αβ heterodimeric glycoproteins have been identified as cellular receptors or entry cofactors for many viruses, including rotaviruses. The α2β1, α4β1, and α4β7 integrins are involved in rotavirus-cell binding and entry, and the αVβ3 and αXβ2 integrins are proposed to facilitate cell entry (17, 28, 29, 32, 34, 46, 47, 73). Of these integrins, α2β1, αVβ3, and αXβ2 facilitate rotavirus attachment and entry into the Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cell line (30).

Two viruses that use β1 and β3 integrins as entry receptors have been shown to modulate cellular integrin expression. The α2β1, αVβ3, and α6β1 integrins are important human cytomegalovirus receptors (23). Human cytomegalovirus infection has been shown to down-regulate α2β1 and α5β1 but up-regulate α6β1 on endothelial cells, down-regulate α1β1 on fibroblasts, and up-regulate β1 integrins on monocytes and prostate tumor cells to facilitate motility (8, 60, 63, 68). Nonpathogenic and pathogenic hantaviruses use β1 and β3 integrins, respectively, for endothelial cell entry. Irrespective of this receptor specificity, hantaviruses induced increased endothelial cell expression of β1 and β3 integrins (27).

Several viruses that use non-integrin receptors can modulate integrin expression to produce an altered cellular adhesion that may impact on virus pathogenesis. Ebola virus surface glycoprotein causes αVβ3 integrin down-regulation, leading to cell detachment and death (62, 65, 67, 72). In contrast, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) up-regulates αV integrins in transformed B lymphocytes, increasing cell proliferation and invasion (37). The EBV-associated up-regulation of α6 integrins might promote nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis (54).

In the only study of integrin protein expression modulation by rotavirus reported to date, α5β1 expression on Caco-2 cells was unaltered by SA11 rotavirus at 8 h postinoculation (p.i.) (21). Microarray analysis showed that levels of α2, α6, and β1 integrin subunit mRNA increased 3.1-, 2.7-, and 2.8-fold, respectively, in rhesus monkey rotavirus (RRV)-infected Caco-2 cell cultures at 16 h p.i., compared with levels in mock-infected cells (19). Levels of these integrin mRNAs were unaltered at 6 h or 12 h p.i. The expression of β3 was not up-regulated on the basis of the criteria used, and α5 mRNA levels were not analyzed (19).

Rotavirus infection increases integrin mRNA levels by an unknown mechanism. However, several signaling pathways have been implicated in controlling integrin expression. Leukotriene D4 stimulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 [COX-2])-dependent prostaglandin production can regulate adhesion and migration of Caco-2 cells by up-regulating α2β1 expression (24, 50, 58). As levels of COX-2 mRNA and prostaglandins are increased after rotavirus infection (19, 71), COX-2 signaling could be involved in rotavirus-induced alterations in integrin mRNA expression. Expression of α2β1 integrin is positively regulated by the AP-1 transcription factor under the control of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) ERK1/2 (22, 75). During rotavirus infection, AP-1 activation is influenced by the MAPKs c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38, so integrin expression might be regulated by MAPK activation (12, 35, 39). Furthermore, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent increases in β1 integrin expression on intestinal cells following treatment with bacterial endotoxin suggest that PI3K signaling might influence β1 integrin regulation by rotavirus (56).

In this study, we have characterized the regulation of integrin expression following rotavirus infection and the subsequent effects on cell adhesion and virus replication. The α2β1, αVβ3, αVβ5, α5, and β2 integrins were chosen for analysis based on their predominance on rotavirus-permissive intestinal cells (33, 36, 42, 50, 74) and the role of a subset in rotavirus cell entry. It is demonstrated that rotavirus infection of intestinal cells differentially regulates rotavirus receptor and non-receptor integrin mRNA and protein expression by a PI3K-dependent pathway that is activated by infection. The differential regulation of integrins, observed in infected cells only, was independent of integrin receptor binding and dependent on viral replication. The modulation of integrin levels might be important for rotavirus replication, as inhibition of PI3K-dependent α2β1 expression resulted in decreased collagen adhesion by infected cells and reduced infectious virus yield.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents.

Monoclonal antibodies to the α2 integrin subunit (12F1-H6, immunoglobulin G2a [IgG2a]; and AK7, IgG1) were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) and AbD Serotec (Kidlington, United Kingdom), respectively. Antibodies P4H9-G11 (β2 integrin subunit), LM609 (αvβ3 integrin), W6/32 (major histocompatibility complex [MHC] class I), and isotype control MOPC21 (IgG1) were obtained as previously described (29). Antibody P1F6 (αVβ5 integrin, IgG1) was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Additional control monoclonal antibodies UPC10 (IgG2a) and FLOPC21 (IgG3) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and matched with test antibody for isotype, diluent type, and protein concentration. Antibody A091 (α5 integrin subunit [IgG1]) was obtained by participation of B.S.C. in the Sixth International Workshop on Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens (17). Rabbit antibodies to phospho-Akt (Ser473; monoclonal) and β-actin (polyclonal) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to RRV were produced as described previously (18). Rotavirus antibody-negative rabbit serum was used as a negative control. Pharmacological agents that inhibit the kinase activity of COX-2 (PTPBS), the ERK1/2 kinase MEK (PD98059), p38 (SB203580), and PI3K (LY294002) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to give stock solutions. Wortmannin, bovine pancreatic insulin, type I collagen from human placenta, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were obtained from Sigma.

Cell lines and viruses.

The colorectal adenocarcinoma (HT-29) cell line was obtained from the ATCC and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagles' medium (Thermo Electron, Melbourne, Australia), containing 0.075% (wt/vol) sodium bicarbonate, 20% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS), 20 mM HEPES (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), 26.6 μg/ml gentamicin (Pharmacia, Bentley, WA, Australia), 2 μg/ml amphotericin B (Fungizone: Apothecon, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ), and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Caco-2 and MA104 cells were propagated as described previously (47). K562 and α2-K562 cells were maintained and monitored for surface integrin expression as previously described (34).

The origins of RRV (P5B[3],G3), porcine rotavirus CRW-8 (P9[7],G3), and human rotaviruses Wa (P1A[8],G1) and 10/76 (P2A[6],G2) have been described previously (16, 51). Viruses were cultivated in MA104 cells with trypsin, purified by glycerol gradient ultracentrifugation, and titrated by immunofluorescent infectivity assay in MA104 cells as described previously (34, 40).

Psoralen inactivation of rotavirus infectivity.

Rotavirus infectivity was inactivated as described previously (31). Inactivated virus showed undetectable infectivity at a dilution of 1:100 and was recognized to the same level at the same dilution as the original purified infectious virus by rabbit antiserum to RRV in an enzyme immunoassay that was described previously (18), showing that virus antigenicity was unaltered by inactivation.

Inhibitor toxicity assay.

The potential toxicity of PTPBS, PD98059, SB203580, wortmannin, and LY294002 was tested by examining their effects on cellular metabolic activity using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One solution cell proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Confluent cell monolayers in 96-well trays were left untreated or treated with inhibitors in serum-free medium for 16 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. CellTiter 96 solution was incubated with cells for 1 h, and the absorbance at 490 nm was recorded with a microplate reader.

Flow cytometric analysis of viral and cellular protein expression.

For analysis of viral antigen and total integrin or MHC class I expression, virus infectivity was activated with porcine trypsin (Sigma; 10 μg/ml) at 37°C for 20 min and added at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI), in a total volume of 200 μl of serum-free medium, to confluent cell monolayers in 24-well trays (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany). Following virus adsorption for 1 h, the inoculum was removed and replaced by serum-free medium. When utilized, inhibitors or DMSO was present at the given concentrations in both the viral inoculum and the medium added to cells following inoculum removal, unless otherwise indicated. Inhibitor presence during inoculation did not affect infectivity (data not shown). At the indicated times p.i., cell monolayers were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and detached by incubation at 37°C for 5 min in PBS containing 0.1% (wt/vol) trypsin (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) and 0.02% (wt/vol) EDTA (PBS-trypsin-EDTA). Cells were permeabilized by methanol fixation for 7 min at −20°C. For analysis of each integrin or MHC class I, duplicate aliquots of 3 × 104 cells were reacted for 45 min on ice with the specified test or control mouse antibody diluted to 20 μg/ml in PBS-FCS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) NaN3 (PBS-FCS-Az). Washed cells were reacted as described above with allophycocyanin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) diluted 1:50 in PBS-FCS. For virus antigen detection, washed cells were reacted with rabbit polyclonal antibodies to RRV or control polyclonal antibodies diluted 1:500, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Chemicon) at a 1:50 dilution. Antibodies to rotavirus and cellular proteins were combined for dual staining of virus antigen and each protein. Cellular fluorescence was analyzed on a FACSort flow cytometer with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD). Infected or uninfected populations were gated on the basis of virus antigen expression.

The effect of insulin on integrin expression was determined by treatment of cell monolayers with insulin (10 μg/ml) for 4 h. Treated cells were incubated in fresh medium for a further 12 h before flow cytometric analysis as described above.

Cell surface protein expression was analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously (47). Briefly, cells were infected, detached, stained with mouse antibodies, fixed with 1% (vol/vol) ultrapure formaldehyde (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) in PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Cellular RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Confluent cell monolayers in 24-well trays were infected with rotavirus at an MOI of 20 or mock infected with harvests of uninfected MA104 cells that had been trypsin treated and diluted as for virus-infected cells. In some experiments, LY294002 or DMSO was included at the indicated concentrations in the virus inoculum and medium added to cells after inoculum removal. At 16 h p.i., total RNA from 6 × 106 cells was collected using the RNeasy Midi kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Relative levels of α2, α5, αV, β1, β3, and COX-2 mRNA in mock-, RRV-, and CRW-8-infected cells were determined by using real-time PCR. Specific forward and reverse primer sets were designed using Primer Express software (version 1.5; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and purchased from Geneworks (Hindmarsh, SA, Australia) as listed: α2 (forward, 5′-TTGAAGCCTATTCTGAGACTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-CTTGAGCAGCTGGTATTTGTCG-3′), α5 (forward, 5′-ATCTCAACAACTCGCAAAGCG-3′; reverse, 5′-TTACTGGGAATAGCACTGC-3′), αV (forward, 5′-TCTTCTCTCGGGACTCCTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-CCGAAGTAACTTCCCTCG-3′), β1 (forward, 5′-TGCCATCATGCAAGTTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-ACCAAGTTTCCCATCTCCAGC-3′), β3 (forward, 5′-ATGCATCCCACTTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-ACACTGCCCGTCATTAG-3′), COX-2 (forward, 5′-TCAGCCATACAGCAAATCC-3′; reverse 5′-TCCTGTCCGGGTACAATCG-3′) and 18S rRNA (forward, 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′; reverse, 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′). The primer concentrations and dynamic range of RNA were optimized for each real-time PCR target. For each reaction, diluted target mRNA (5 μl) was added to 20 μl of a mix containing Multiscribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems), forward and reverse primers (300 or 900 μM), RNase-free water, RNase inhibitor, and 12.5 μl of 2× SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), which contained nucleotides, AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase, and optimized buffer components. Real-time PCRs were performed on an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems) with an amplification profile of 30 min at 48°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 45 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. As a no-template control, diluted target mRNA was replaced with RNase-free water. All samples and standards were tested in triplicate in at least three independent experiments. The data were analyzed with the sequence detector software V1.7 (Applied Biosystems). Transcript abundance was calculated using the comparative change in threshold cycle (ΔCT) method with 18S rRNA as the normalization standard. Levels of 18S rRNA were unaltered by RRV and CRW-8 infection of Caco-2 cells (data not shown). Differential expression based on real-time PCR measurements was defined as a change in transcriptional accumulation of ≥1.5. The specificity of amplification of each assay was verified by electrophoretic separation of PCR products on agarose gels and dissociation curves generated by slow denaturation of the PCR end products that were analyzed using ABI Prism 7700 dissociation curve analysis software V1.0 (Applied Biosystems).

Detection of Akt activity.

Confluent cell monolayers in 24-well trays were serum starved for 24 h and then mock infected, infected with purified rotavirus (MOI of 10), or treated with insulin (10 μg/ml). At given times, cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), containing 1 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma), aprotinin (10 μg/ml; Sigma), and leupeptin (5 μg/ml; Sigma) for 5 min at 4°C. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation and boiled with sample buffer. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred to a membrane as described previously (35). After blocking in PBS containing 2% (wt/vol) BSA and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBS-BSA) for 1 h at 37°C, the membrane was washed with PBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBS-T) and reacted with antibody to phospho-Akt diluted in PBS-BSA for 18 h at 4°C. After washing in PBS-T, membranes were washed in PBS-T and reacted with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit antibody (Chemicon), optimally diluted in PBS-T, for 1.5 h at room temperature. Bound antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) with ECL Hyperfilm (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) as specified by the manufacturer. Membranes were stripped as previously described (35) and reprobed as described above with antibody to β-actin diluted in PBS-BSA. Films were scanned, and densitometric analysis was carried out using Image Gauge software (V3.3, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell adhesion assay.

Plates (96 wells) were coated (100 μl) with collagen or BSA (10 μg/ml) in PBS overnight at 4°C. Unbound protein was removed by washing twice with PBS. Further incubations were carried out at 37°C in 95% (vol/vol) air-5% (vol/vol) CO2. Wells were blocked with 1% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS for 1 h, followed by three washes with PBS. Confluent cell monolayers in 24-well trays were infected with RRV or CRW-8 at an MOI of 10 in medium containing 20 μM PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) or matched DMSO control. At 16 h p.i., cells were detached with PBS-trypsin-EDTA, washed, and resuspended in serum-free medium containing 2% (wt/vol) BSA to block nonspecific binding. For adhesion blockade, 1.5 × 104 cells in 300 μl were reacted with anti-α2 or control antibody at 20 μg/ml and incubated with rolling for 30 min. Cells (5.0 × 103 per well) were allowed to adhere in triplicate to coated wells for 1 h. Unbound cells were removed by three gentle washes with PBS. Following medium replacement, cells were allowed to spread for a further 4 h. Adherent cells were counted under a light microscope. Bound cells (round) were distinguished from spreading cells (extended with protrusions) by morphology and enumerated separately.

Analysis of cell detachment during infection.

Confluent cell monolayers, cultured in 24-well trays coated (200 μl) with collagen as described above or untreated, were infected at a MOI of 0.1 in the presence of PI3K inhibitor LY294002 at 20 μM or a DMSO-matched control. Additional LY294002 at 20 μM was added at 24 h p.i. to replace any lost activity. The number of cells detached at the given times after infection was determined by counting in a hemocytometer under a light-phase microscope.

Rotavirus growth assay.

Rotavirus growth assays in adherent cell lines were performed as previously described (47). Briefly, cell monolayers growing in 24-well trays that had been either untreated or pretreated with collagen, as described above, were washed twice with medium. Trypsin-activated virus (MOI of 0.1) was adsorbed to cells for 1 h at 37°C. Monolayers were washed twice, medium containing 1 μg/ml porcine trypsin was added, and cultures were incubated for the indicated times. Virus replication was terminated by freezing at −70°C, and infectious virus was harvested by two rounds of freezing and thawing. Infectious virus was quantitated by infectivity titration in MA104 cells.

RESULTS

Rotavirus replication in intestinal cells led to differential regulation of integrin expression independently of integrin usage by virus during cell attachment or entry.

The effect of rotavirus infection on the cellular expression of α2β1, β2, αVβ3, and α5β1 integrins and MHC class I was determined using dual-color flow cytometric analysis of fixed cells stained for rotavirus antigen and each cellular protein. As α2 and α5 subunits pair with β1 only, their expression reflects α2β1 and α5β1 levels. The β2 subunit pairs with αL, αM, αX, and αD, so β2 expression indicates any β2 heterodimer present (38). The anti-αVβ3 antibody used is specific for this heterodimer (11). Initially, the proportions of cells infected with rotaviruses at a range of MOI were determined from density plots, such as those illustrated for RRV at an MOI of 10 in Fig. 1. As shown in Table 1, intestinal cell lines Caco-2 and HT-29 were slightly less susceptible to rotavirus infection than the kidney cell line MA104. At MOI of 3.5 and 10, 93% to 95% of MA104 cells were infected at 16 h p.i. by RRV and CRW-8. In contrast, maximum levels of infection of Caco-2 and HT-29 cells by these rotaviruses occurred at an MOI of 10 (77% to 83%). Human rotaviruses Wa and 10/76 infected fewer Caco-2 cells (69%) than RRV or CRW-8 (77% to 82%).

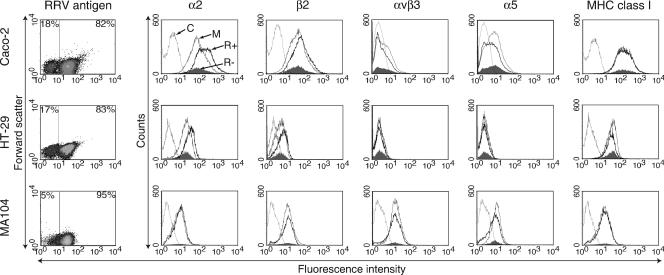

FIG. 1.

RRV infection of intestinal cells induced differential regulation of total cellular expression of integrins α2, β2, αVβ3, and α5 but not MHC class I. Caco-2, HT-29, and MA104 cells were collected at 16 h after RRV infection at an MOI of 10, stained for viral antigen and cellular proteins, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Numerical data on the density plots represent the mean percentage of cells that were present in the infected (right) or uninfected (left) gate. These gates were used to generate histograms of integrin and MHC class I expression in infected cells (R+; heavy line), cells uninfected following exposure to RRV (R−; filled histogram), mock-infected cells (M; medium line), and cells treated with isotype-matched control antibody (C; faint line). These data are representative of those obtained from two or three independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Rotavirus infection of Caco-2 and HT-29 cells led to altered total levels of expression of α2, β2, αVβ3, and α5 integrins (when present) but not MHC class I

| Cell line | Virus | Virus MOI | % Infected cellsa | Total cellular expression of protein at 16 h p.i.

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α2

|

β2

|

αVβ3

|

α5

|

MHC class I MFI

|

|||||||||||||

| MFIb

|

Fold change in Ie | MFI

|

Fold change in I | MFI

|

Fold change in I | MFI

|

Fold change in I | ||||||||||

| UIc | Id | UI | I | UI | I | UI | I | UI | I | ||||||||

| Caco-2 | RRV | 0.1 | 10 ± 1 | 62 ± 0 | 140 ± 8 | 2.1 | 33 ± 0 | 58 ± 2 | 1.7 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 | 6.5 ± 0.0 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 | 105 ± 5 | 110 ± 3 |

| 3.5 | 66 ± 3 | 64 ± 0 | 138 ± 4 | 2.2 | 33 ± 0 | 51 ± 1 | 1.5 | 3.8 ± 0.0 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.0 | 0.7 | 101 ± 5 | 100 ± 2 | ||

| 10 | 82 ± 4 | 60 ± 0 | 132 ± 2 | 2.2 | 32 ± 0 | 54 ± 1 | 1.6 | 3.7 ± 0.0 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 | 102 ± 1 | 102 ± 4 | ||

| CRW-8 | 0.1 | 9 ± 1 | 63 ± 3 | 132 ± 7 | 1.9 | 32 ± 1 | 56 ± 1 | 1.6 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 | 112 ± 4 | 110 ± 2 | |

| 3.5 | 66 ± 3 | 63 ± 2 | 123 ± 6 | 1.9 | 33 ± 2 | 49 ± 1 | 1.5 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 0.8 | 6.2 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 | 103 ± 1 | 104 ± 3 | ||

| 10 | 77 ± 2 | 60 ± 2 | 126 ± 4 | 2.1 | 32 ± 2 | 52 ± 3 | 1.6 | 3.6 ± 0.0 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 | 106 ± 5 | 101 ± 2 | ||

| Wa | 10 | 69 ± 3 | 63 ± 1 | 144 ± 1 | 2.4 | 33 ± 2 | 60 ± 1 | 1.8 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 | 105 ± 7 | 102 ± 2 | |

| 10/76 | 10 | 69 ± 4 | 61 ± 1 | 137 ± 2 | 2.3 | 33 ± 1 | 59 ± 1 | 1.8 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 0.7 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 | 101 ± 2 | 102 ± 2 | |

| HT-29 | RRV | 10 | 83 ± 5 | 6.9 ± 0.4 | 15 ± 1 | 2.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 1.5 | 2.3 ± 0.1f | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | 2.3 ± 0.1f | 2.4 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 32 ± 2 | 37 ± 1 |

| CRW-8 | 10 | 78 ± 4 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 0 | 2.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 1.4 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | 33 ± 2 | 32 ± 1 | |

| MA104 | RRV | 0.1 | 19 ± 3 | 8.1 ± 0.0 | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 1.0 | 11 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 1.0 | 14 ± 0 | 15 ± 1 | 1.0 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.6 ± 0.2 | 1.0 | 13 ± 1 | 14 ± 1 |

| 3.5 | 94 ± 3 | 8.1 ± 0.2 | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 1.0 | 12 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 1.0 | 13 ± 0 | 14 ± 1 | 1.0 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 0 | ||

| 10 | 95 ± 2 | 8.3 ± 0.1 | 8.3 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 12 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 1.0 | 14 ± 0 | 14 ± 1 | 1.0 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 0 | ||

| CRW-8 | 0.1 | 14 ± 1 | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 1.0 | 12 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 1.0 | 13 ± 1 | 14 ± 1 | 1.0 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | 13 ± 0 | 14 ± 1 | |

| 3.5 | 93 ± 1 | 8.0 ± 0.2 | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | 12 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 1.0 | 13 ± 0 | 14 ± 1 | 1.0 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | 13 ± 0 | 13 ± 0 | ||

| 10 | 93 ± 3 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | 12 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 1.0 | 14 ± 0 | 14 ± 1 | 1.0 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | 1.0 | 14 ± 1 | 13 ± 0 | ||

| K562 | RRV | 10 | 36 ± 2 | 3.6 ± 0.2g | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 | NDh | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| α2-K562 | RRV | 10 | 81 ± 6 | 61 ± 2 | 62 ± 1 | 1.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Mean percentage (±SD) of cells within rotavirus-inoculated cultures that contained rotavirus antigen, as determined by flow cytometry.

MFI values represent the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± range, calculated from duplicates. Analyses were repeated two or three times, with similar levels of integrin regulation observed in each experiment. Data from a representative experiment are given. MFI values obtained using isotype control antibodies in Caco-2 cells were 3.3 for α2 and MHC class I and 2.6 for β2, αVβ3, and α5. In HT-29 cells, the isotype control MFI values were 2.4 for α2, αVβ3, α5, and MHC class I and 2.3 for β2. These control values in MA104 cells were 2.0 for α2 and MHC class I (MOI of 0.1), 2.1 for MHC class I (MOI of 3.5 and 10), 3.9 for β2, and 3.2 for αVβ3 and α5. In K562 and α2-K562 cells, the MFI isotype control value was 3.6.

UI, uninfected cells within rotavirus-inoculated cultures as determined by flow cytometry.

I, infected cells within rotavirus-inoculated cultures, as determined by flow cytometry.

Change (fold) in I defined as MFI of I/MFI of mock-infected cells. The MFIs of UI and mock-infected cells were indistinguishable for all cellular proteins tested.

Expression of αVβ3 and α5 integrins on HT-29 cells was not detected.

K562 cells lack α2.

ND, not done.

To separately examine infected and uninfected cells within each rotavirus-inoculated culture, levels of integrins and MHC class I were analyzed on cell populations gated according to rotavirus antigen expression. In representative examples of the flow cytometric histograms obtained (Fig. 1), shifts in histograms of the RRV-infected population within RRV-inoculated Caco-2 cells (MOI of 10) could be observed that indicated up-regulation of α2 and β2 integrins and down-regulation of αVβ3 and α5 integrins. Similar alterations in α2 and β2 occurred in RRV-infected cells within RRV-inoculated HT-29 cultures. However, HT-29 cells did not express αVβ3 or α5 integrins, in agreement with previous reports (11, 59). No shift in the αVβ3 and α5 histograms of HT-29 cells was detected, so their expression was not induced de novo by infection. In contrast to the intestinal cell lines, integrin expression was unaltered in the infected cells within RRV-inoculated MA104 cultures. MHC class I expression was unaltered in RRV-infected Caco-2, HT-29, and MA104 cells.

These studies were extended to additional rotaviruses, cell lines, and MOI (Table 1). Compared with mock-infected cells, inoculation of Caco-2 cells with RRV, CRW-8, Wa, or 10/76 rotavirus (MOI of 10) produced increased expression by infected cells of α2 (2.1- to 2.4-fold) and β2 (1.6- to 1.8-fold) and decreased expression of αVβ3 (0.7-fold) and α5 (0.8-fold). The change (fold) in integrin expression by Caco-2 cells expressing RRV or CRW-8 antigen did not vary with MOI over the range of 0.1 to 10, although only 9 to 10% of cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1 (Table 1). RRV or CRW-8 infection of HT-29 cells resulted in increased expression of α2 (2.1-fold) and β2 (1.4- and 1.5-fold, respectively) at 16 h p.i. over mock-infected cells. These increases were proportionally the same as in Caco-2 cells, even though HT-29 cells expressed five- to ninefold less α2 and β2 than Caco-2 cells. Irrespective of MOI, total integrin levels in uninfected Caco-2 and HT-29 cells exposed to RRV, CRW-8, Wa, or 10/76 were similar to those in mock-infected cells (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Thus, the differential expression of integrins was not caused by a soluble factor secreted from infected cells. In contrast to integrins, total MHC class I expression was unaltered by rotavirus infection in Caco-2 and HT-29 cells. This highlights the specificity of integrin regulation by infected intestinal cells (Fig. 1 and Table 1). RRV or CRW-8 infection of MA104 cells did not affect expression of α2, β2, αVβ3, α5, or MHC class I (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Also, α2 levels in K562 or α2-K562 cells were unaltered by RRV infection (Table 1). Overall, rotavirus inoculation of intestinal cells led to differential regulation of α2β1, β2, αVβ3, and α5β1 expression in infected cells within inoculated cultures, provided the integrin was initially present. This regulation was independent of virus usage of α2β1, β2, and αVβ3 for cell attachment and entry, as CRW-8 and 10/76 do not use these integrins but regulated integrin expression similarly to the integrin-using rotaviruses RRV and Wa. These studies also show that αVβ3 is not essential for cell entry by integrin-using rotaviruses, as HT-29 cells lacked αVβ3 but were infected by RRV similarly to Caco-2 cells (Table 1).

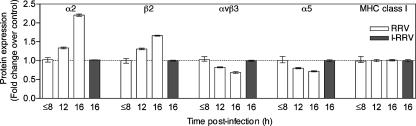

The kinetics of integrin expression regulation by rotaviruses were examined in Caco-2 cells (Fig. 2). Cellular integrin levels in RRV-infected cells first altered between 8 and 12 h p.i. with maximum regulation at 16 h p.i. The unchanged α5 expression at 8 h p.i. observed in this study confirms the previous report that α5 is unaltered at this time (21). The kinetics of integrin regulation in Caco-2 cells infected with CRW-8 or RRV were indistinguishable (data not shown). Caco-2 cell exposure to inactivated RRV did not alter cellular integrin expression (Fig. 2). This indicates that rotavirus replication was required for differential regulation of integrin expression.

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of induction of alterations in total cellular integrin expression in intestinal cells by rotavirus and requirement for replicating virus. Caco-2 cells were infected at an MOI of 10 with RRV or treated with inactivated RRV (I-RRV). Cells collected at the indicated times p.i. were stained for expression of cellular proteins and viral antigen and analyzed by flow cytometry. For RRV-infected cultures, only cells positive for viral antigen expression were analyzed for integrin or MHC class I expression, while the entire population of cells treated with I-RRV was analyzed. Data represent the mean ± range (in duplicate samples) of the change in the expression of integrin or MHC class I protein relative to its expression in mock-infected cells. These data are representative of those obtained from two independent experiments.

Regulation of cellular integrin expression by rotavirus infection occurred similarly at the surface and overall.

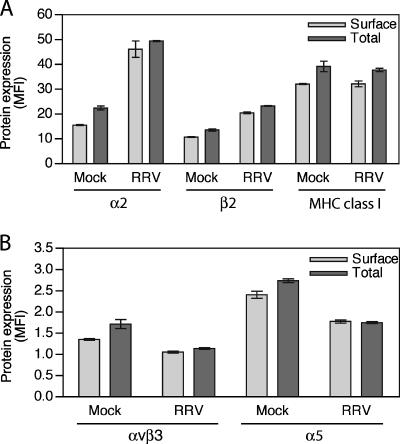

To determine if rotavirus infection alters integrin expression at the cell surface, where integrins have particular functional significance, unfixed, nonpermeable Caco-2 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for α2, β2, αVβ3, and α5 expression in parallel with fixed, permeable cells (Fig. 3). As rotavirus antigen could not be analyzed in unfixed cells, infected cells were not distinguished from uninfected cells in these experiments. However, the majority (77 to 82%) of cells were infected at the MOI (10) chosen (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 3, RRV infection produced similar alterations in total levels of α2, β2, αVβ3, and α5 expression to earlier experiments (Fig. 1 and 2 and Table 1). Surface expression of these integrins on RRV-infected Caco-2 cells was modulated to a similar extent to the total cellular level (Fig. 3A and B). CRW-8 infection of Caco-2 cells at the same MOI similarly altered total and cell surface expression of α2, β2, αVβ3, and α5 (data not shown). The levels of cell surface and total MHC class I expression were unaltered following Caco-2 cell infection with RRV or CRW-8 (Fig. 3A) (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of integrin and MHC class I expression on the cell surface with the total cellular level of expression following rotavirus infection. Data for α2 integrin, β2 integrin, and MHC class I (A) and integrins αvβ3 and α5 (B) are shown. Caco-2 cells were mock infected or infected with RRV at an MOI of 10 and harvested at 16 h p.i. Unfixed and methanol-fixed cells were stained for integrin or MHC I expression as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the mean ± range (from duplicate samples) of the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of protein expression in the entire cell population. These data are representative of those obtained from two independent experiments.

Rotavirus-induced regulation of integrin expression in intestinal cells required PI3K signaling at an early stage of infection.

The signaling events leading to the differential regulation of integrins following rotavirus infection of Caco-2 and HT-29 cells were investigated through the use of specific inhibitors of p38, COX-2, and MEK. The role of PI3K also was examined, as PI3K-dependent increases in β1 integrin expression by intestinal cells have been observed (56). Cells were infected in the presence of pharmacological inhibitors of p38 (SB203580; 50 μM), COX-2 (PTPBS; 23 μM), MEK (PD98059; 60 μM), and PI3K (LY294002; 20 μM; wortmannin, 10 μM). These inhibitor concentrations did not affect the metabolic activity of Caco-2 and HT-29 cells, as activities measured in the presence and absence of inhibitor varied by <5%. Total cellular expression of integrins and MHC class I was analyzed at 16 h p.i. using flow cytometry. In addition to the integrins analyzed above, levels of αVβ5 integrin expression were examined using a monoclonal antibody specific for this heterodimer. Following RRV infection, αVβ5 levels in Caco-2 and HT-29 cells were reduced by 43% and 52%, respectively (Fig. 4A and C). Inhibitors of p38, COX-2, and MEK did not affect integrin protein expression in RRV- or CRW-8-infected Caco-2 cells compared with that in infected cells treated with DMSO alone (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, PI3K inhibitors LY294002 and wortmannin extensively blocked the differential regulation of integrins caused by rotavirus in Caco-2 and HT-29 cells (Fig. 4). RRV or CRW-8 infection of Caco-2 cells in the presence of these inhibitors blocked α2 and β2 up-regulation by 71 to 90% and αVβ3, αVβ5, and α5 down-regulation by 44 to 99% compared with control cells (Fig. 4A and B). Similarly, α2 and β2 up-regulation following RRV or CRW-8 infection of HT-29 cells was reduced by 60 to 83% in the presence of PI3K inhibitors and αVβ5 down-regulation after RRV infection was reduced by 79% (Fig. 4C). For Caco-2 and HT-29 cells, LY294002 inclusion during the first 5 h after RRV infection was almost as effective in restoring α2 to control levels as LY294002 treatment for 16 h, whereas LY294002 treatment for 5 to 16 h after infection had little effect on α2 up-regulation (Fig. 4A and C). Thus, PI3K signaling early in the rotavirus replicative cycle was required for regulation of α2 expression. MHC class I expression following rotavirus infection was unchanged by treatment with PI3K, p38, COX-2, and MEK inhibitors (Fig. 4A, B, and C). This demonstrates the specificity of PI3K inhibition for blockade of rotavirus-induced integrin regulation. Overall, these data show that integrin expression modulation after rotavirus infection of intestinal cells required PI3K signaling in the first 5 h after infection and was independent of p38, COX-2, and MEK kinases.

FIG. 4.

Effect of signaling pathway inhibitors on rotavirus-induced integrin regulation in intestinal cells. Caco-2 (A and B) and HT-29 (C) cells were infected at a MOI of 10 in the presence of chemical inhibitors of COX-2 (PTPBS [PT]), MEK (PD98059 [PD]), p38 (SB203580 [SB]), and PI3K (wortmannin [Wort] and LY294002 [LY]), or matched DMSO controls, for 16 h. In addition, LY was present only from 0 to 5 h or 5 to 16 h p.i. for RRV infections in panels A and C. Collected cells were examined by flow cytometry after fixation and staining for expression of viral antigen and cellular proteins. Rotavirus-infected cells were gated by viral antigen expression, and cellular protein expression was determined in infected cells. Data are shown as the mean ± range (from duplicate samples) of the change (fold) in expression of the indicated protein in infected cells compared with mock-infected cells (dotted lines).

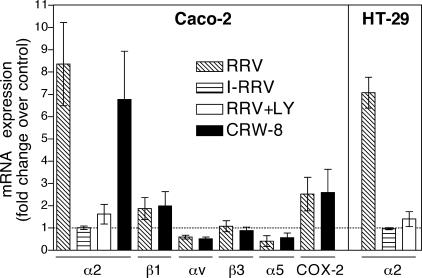

Alterations in integrin mRNA levels during rotavirus infection of intestinal cells.

To examine integrin expression regulation at the transcriptional level, relative levels of integrin mRNA within rotavirus- and mock-infected Caco-2 and HT-29 cells were determined by real-time PCR, in the presence or absence of LY294002. COX-2 mRNA expression is elevated during rotavirus infection of Caco-2 cells and so was included as a positive control (19). For these experiments, total RNA was isolated at 16 h p.i. from cells infected with RRV or CRW-8 (MOI of 10). The changes (fold) in relative amounts of integrin and COX-2 mRNA in rotavirus-infected Caco-2 cells over mock-infected (control) cells are summarized in Fig. 5. Rotavirus infection produced increases of 8.4-fold (RRV) and 6.8-fold (CRW-8) in α2 mRNA levels, 1.9-fold (RRV) and 2.0-fold (CRW-8) in β1 mRNA levels, and 2.5-fold (RRV) and 2.6-fold (CRW-8) in COX-2 mRNA levels. In contrast, αV mRNA levels were reduced to 0.6-fold (RRV) and 0.5-fold (CRW-8) and α5 mRNA levels to 0.4-fold (RRV) and 0.6-fold (CRW-8). Levels of β3 mRNA in infected cells were unaltered compared with those in mock-infected cells, and β5 was not analyzed. Due to primer-dimer formation, β2 mRNA levels could not be determined using two alternative primer sets. A useable dynamic range could not be obtained in the Taqman gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems), again precluding accurate measurement of β2 mRNA. RRV infection in HT-29 cells produced a 7.1-fold increase in α2 mRNA levels, similar to Caco-2 cells. Inactivated RRV did not affect α2 mRNA levels in either cell line. PI3K inhibitor LY294002 reduced the elevated α2 mRNA levels in Caco-2 and HT-29 cells by 80 to 81% (Fig. 5). These data indicate that PI3K-dependent changes in integrin protein expression following rotavirus infection were reflected at the transcriptional level.

FIG. 5.

Rotavirus infection regulated integrin mRNA expression in intestinal cells. Caco-2 and HT-29 cells were mock infected or infected with RRV, inactivated RRV (I-RRV), or CRW-8 at an MOI of 10 for 16 h. For some experiments, cells were infected in the presence of PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (LY). Cellular RNA was extracted and analyzed by real-time PCR for levels of integrin or COX-2 mRNA. Data are expressed as the change (fold) in mRNA expression in infected cells compared with mock-infected cells (dotted line) and represent the mean ± SD from at least three independent reactions, each performed in triplicate.

Rotavirus infection induced PI3K-dependent Akt phosphorylation in intestinal and kidney cells.

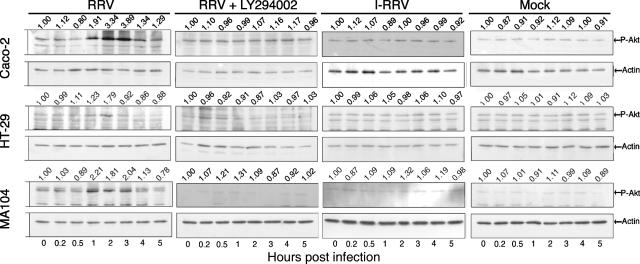

The observed reliance of rotavirus-induced integrin regulation on PI3K activity suggested that the PI3K signaling pathway might be activated during rotavirus infection. We therefore examined activation of the kinase Akt, which occurs rapidly following PI3K activation (26). Akt activation was analyzed in Western blots of infected-cell lysates using antibodies specific to Akt phosphorylated at Ser473 (P-Akt), as shown in Fig. 6 for RRV. Data for CRW-8 were similar to those for RRV and are not shown. Compared with mock-infected cells, elevated levels of P-Akt were detected in RRV- or CRW-8-infected Caco-2 and MA104 cells at 1 h p.i. and were sustained until 3 to 4 h p.i. Increased P-Akt was detected only at 2 h p.i. by RRV and CRW-8 in HT-29 cells. Following these transient increases, P-Akt levels returned to control levels and remained so at all subsequent times analyzed (8, 12, and 16 h [data not shown]). The P-Akt peak in Caco-2 cells occurred at 2 to 3 h p.i., with 3.89- and 3.62-fold increases over controls in RRV- and CRW-8-infected cells, respectively. In MA104 cells, maximal P-Akt levels were detected at 1 to 2 h p.i., with increases of 2.21- and 2.73-fold over controls in RRV- and CRW-8 infected cells, respectively. HT-29 cells showed the lowest increases in P-Akt following infection of 1.79-fold (RRV) and 1.91-fold (CRW-8) at 2 h p.i. Akt activation in all cell lines was dependent on PI3K activity, as the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 reduced RRV- and CRW-8-induced Akt phosphorylation back to control levels. Inactivated RRV (Fig. 6) and CRW-8 (data not shown) did not induce Akt phosphorylation. Overall, rotavirus infection induced a transient activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway that was dependent on virus replication. The timing of this activation coincided with the period after infection in which PI3K activity was required for integrin expression regulation (0 to 5 h). This indicates that rotavirus-induced PI3K activation is important for integrin expression regulation.

FIG. 6.

Rotavirus infection induced PI3K-dependent Akt phosphorylation in MA104, HT-29, and Caco-2 cells. Cells were mock infected or infected with inactivated RRV (I-RRV) or RRV at a MOI of 10 in the presence or absence of 20 μM LY294002. Cell lysates were collected at the indicated times p.i. and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies specific for Ser473-phospho-Akt (P-Akt) and actin. Bands were identified by size comparison with molecular weight markers. The intensities of Akt phosphorylation relative to actin were determined by densitometric analysis and are indicated above each lane. These data are representative of those obtained from two independent experiments.

PI3K activation by insulin was insufficient for regulation of integrin expression.

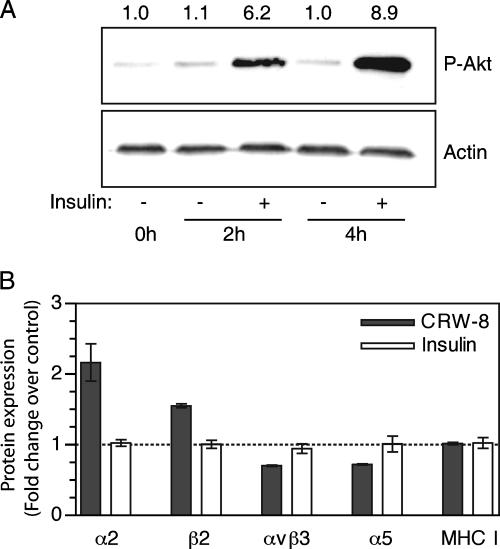

Rotavirus-induced regulation of integrin expression required PI3K activity. To assess if PI3K activation in the absence of rotavirus infection also induces integrin expression modulation, cells were treated with insulin, a strong inducer of PI3K activation (52). Insulin treatment of Caco-2 cells for 2 h and 4 h produced 6- and 9-fold increases in P-Akt over untreated cells, respectively, demonstrating PI3K activation (Fig. 7A). As described above, RRV or CRW-8 infection of Caco-2 cells caused Akt activation at 1 to 4 h p.i., and integrin proteins were maximally regulated at 16 h p.i. To mimic the Akt activation seen during infection, Caco-2 cells were treated with insulin for 4 h and then washed and incubated for a further 12 h without insulin. However, in contrast to rotavirus infection, insulin treatment did not alter integrin expression (Fig. 7B). This demonstrates the specificity of integrin expression regulation by rotaviruses and indicates that other rotavirus-induced signals additional to PI3K activation may be required to regulate integrin expression during infection.

FIG. 7.

Insulin activated PI3K signaling in intestinal cells but failed to regulate integrin expression. (A) Caco-2 cells were treated with insulin at 10 μg/ml for the indicated times, and cell lysates were examined for Akt phosphorylation (P-Akt) and actin by Western blotting. Densitometric analysis was used to determine the intensities of Akt phosphorylation relative to actin, which are indicated above each lane. (B) Caco-2 cells were treated with insulin at 10 μg/ml for 4 h and analyzed 12 h later for total cellular integrin expression by flow cytometry. Mock- and CRW-8-infected Caco-2 cells were similarly analyzed at 16 h p.i. as a positive control. Data are represented as the mean ± range (in duplicate samples) of the change (fold) in expression of the indicated receptor in insulin-treated or infected cells compared with mock-infected cells.

Blockade of integrin regulation by inhibition of PI3K reduced adhesion of rotavirus-infected Caco-2 and HT-29 cells to collagen and virus yield.

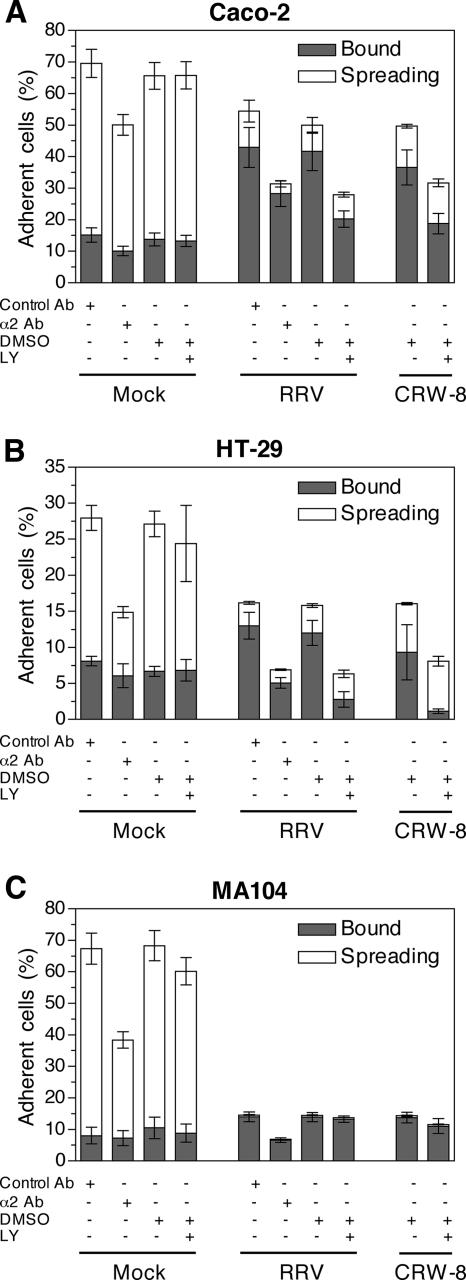

The above studies showed that rotavirus-infected intestinal cells, but not MA104 cells, expressed elevated surface levels of α2β1 integrin, a key ligand for adhesion of these intestinal cells to type 1 collagen (5, 33). The functional significance of the increased α2β1 expression was therefore examined by quantitation of collagen adhesion by mock- and rotavirus-infected Caco-2, HT-29, and MA104 cells. The role of α2β1 in this adhesion was analyzed by anti-α2 antibody blockade (Fig. 8). This antibody reduced collagen adherence by 29% (Caco-2), 48% (HT-29), and 53% (MA104) for mock-infected cells and 38% (Caco-2), 57% (HT-29), and 39% (MA104) for RRV-infected cells. Adhesion of uninfected Caco-2 and HT-29 cells to type 1 collagen was similarly reduced by anti-α2 antibodies in previous studies (33, 36, 50). Our experiments show this function is retained in rotavirus-infected cells. Although fewer HT-29 (26%) than Caco-2 (70%) cells adhered to collagen, HT-29 adhesion showed greater dependence on α2β1. As increased α2β1 expression following rotavirus infection was dependent on PI3K activity, the ability of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 to affect cellular adhesion to collagen also was determined. This inhibitor had no effect on collagen adherence by mock-infected Caco-2, HT-29, or MA104 cells (Fig. 8). Infection reduced adherent Caco-2 cell numbers by 24% compared with mock-infected cells. However, significantly greater reductions of 57% (RRV) and 52% (CRW-8) in adherent Caco-2 cell numbers were observed following infection in the presence of LY294002 compared to DMSO alone (P < 0.0047). Consistent with their greater dependence on α2β1 for collagen adhesion, there were 42% (RRV) and 41% (CRW-8) fewer adherent virus-infected HT-29 cells than mock-infected cells. LY294002 reduced adherence of virus-infected HT-29 cells to collagen by 74% (RRV) and 67% (CRW-8), significantly greater reductions in cellular adherence than those induced by infection alone (P < 0.0038). Thus, PI3K inhibition in Caco-2 and HT-29 cells during infection decreased collagen adhesion. As PI3K inhibition blocked the majority of α2β1 expression up-regulation in rotavirus-infected cells and α2β1 mediated 38 to 57% of collagen adhesion, a substantial part of the reduced collagen adherence after LY294002 treatment was related to lowered α2β1 levels.

FIG. 8.

Effect of anti-α2 integrin antibody and PI3K inhibitor on the adhesion and spreading of mock- and rotavirus-infected cells on type I collagen. Caco-2 (A), HT-29 (B), and MA104 (C) cells were mock infected or infected with RRV or CRW-8 at an MOI of 10 in the presence of control antibody MOPC21 (control Ab), anti-α2 antibody AK7 (α2 Ab), 20 μM LY294002 (LY), or a matched DMSO control. At 16 h p.i., cells were placed in suspension, washed, and incubated on collagen-coated plates for 5 h. Attached cells were counted under a light microscope. Cells that were bound or spreading were distinguished by their morphology. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of cells that were bound or spreading from triplicate determinations. These data are representative of those obtained from two independent experiments, with the exception of the anti-α2 integrin and control antibody blockade, which was conducted once.

MA104 cell adhesion to collagen was reduced by 79% after infection with RRV or CRW-8, a significantly greater effect of infection than with Caco-2 or HT-29 cells (P < 0.015). In contrast to Caco-2 and HT-29 cells, LY294002 did not affect binding of rotavirus-infected MA104 cells to collagen. This indicates the specificity of the reduced intestinal cell adhesion in the presence of this inhibitor. As rotavirus-induced α2β1 up-regulation through PI3K activation was not observed in MA104 cells, the lack of effect of PI3K inhibition in these cells is further evidence that α2β1 up-regulation was responsible for the increased binding of rotavirus-infected intestinal cell lines to collagen.

Various proportions of adherent cells spread on collagen, demonstrating their viability. Rotavirus-infected Caco-2, HT-29, and MA104 cell cultures showed a marked decrease in the number and proportion of attached cells that were spreading compared with mock-infected cells. The proportion of spreading Caco-2 and HT-29 cells following RRV and CRW-8 infection in the absence of LY294002 (14 to 41%; mean ± standard deviation [SD] of 27% ± 10%) was similar to the uninfected proportion (17 to 23%; mean ± SD of 20% ± 3%; Table 1). Additionally, bound infected cell numbers fell by 49% to 52% (Caco-2) and 77% to 88% (HT-29) in the presence of LY294002, but spreading cell numbers were unaltered by LY294002 treatment. Thus, most cells spreading on collagen within rotavirus-infected HT-29 and Caco-2 cultures probably were uninfected. The almost complete absence of spreading MA104 cells after rotavirus exposure likely results from the high proportion of infected cells (93 to 95%; Table 1).

The effect of PI3K-dependent increases in α2β1 expression and adherence to collagen on cell survival and virus replication was investigated. Initially, the proportion of HT-29 and Caco-2 cells grown on collagen that remained adherent after rotavirus infection in the presence or absence of LY294002 was determined (Fig. 9A and B). At 40 h p.i. with RRV or CRW-8, adherent cell numbers fell by 22 to 28% (HT-29; P = 0.01) and 7% (Caco-2; P = 0.01) in the presence of LY294002, compared with the DMSO control (Fig. 9A and B). This indicated that a proportion of HT-29 and Caco-2 cell attachment to collagen during infection was dependent on PI3K activity, consistent with other findings (Fig. 8). Titers of RRV and CRW-8 at 40 h p.i. in these HT-29 cells grown on collagen were reduced by 37% and 27%, respectively, in the presence of LY294002 (Fig. 9C and D; P < 0.008). RRV titers at 40 h p.i. in these Caco-2 cells were reduced by 18% (Fig. 9C; P = 0.002). Both RRV yield and collagen adhesion were reduced to a greater extent in HT-29 than Caco-2 cells. Overall, through α2β1 integrin up-regulation, cellular PI3K activity played a significant role in maintaining cellular adherence (and therefore viability) and the yield of infectious rotavirus.

FIG. 9.

Effect of PI3K inhibition on cell detachment and rotavirus yield in intestinal cells cultured on collagen. Confluent intestinal cell monolayers grown on collagen were mock infected or infected with RRV or CRW-8 at an MOI of 0.1 in the presence of 20 μM LY294002 or a matched DMSO control. The effect of rotavirus infection on detachment of HT-29 (A) and Caco-2 (B) cells was determined. The number of cells detached from infected cell monolayers at the indicated times p.i. is expressed as a percentage of the number of cells detached from untreated cell monolayers. As the number of cells lost from untreated cells did not vary significantly over time, a mean ± standard deviation of 8 × 104 ± 3 × 103 cells (HT-29) or 4 × 104 ± 5 × 103 cells (Caco-2) was used. Data were obtained from triplicate determinations. The effect of PI3K inhibition on the infectious titers of RRV (C) and CRW-8 (D) was analyzed. Virus titers were determined at various times p.i. by infectivity titration. Titers in the indicated cell line are given as the mean ± SD of triplicate counts. These data are representative of those obtained from two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Modulation of integrin expression during virus infection alters the intercellular and extracellular binding properties of infected cells and can have profound effects on cell survival and function. This study shows for the first time that rotaviruses differentially modulate the expression of several integrins in intestinal cells in a process dependent on PI3K activation by virus infection. Blockade of integrin regulation in infected cells using PI3K inhibitors resulted in decreased adhesion of infected cells to collagen via α2β1 and reduced virus replication.

Up-regulation of α2β1 and β2 was evident by 12 h p.i., while αVβ3, αVβ5, and α5β1 were down-regulated at this time. This regulation was observed only in Caco-2 and HT-29 cells, suggesting an intestinal cell-specific mechanism. Changes in integrin expression were not due to a general cellular response to loss of cell viability during rotavirus infection, as Caco-2 cells had lost little viability and metabolic activity at 16 h p.i. when maximum integrin regulation was observed. In contrast, MA104 cells at 16 h p.i. showed significant loss of viability and metabolic activity with no regulation of integrin expression (P. Halasz and B. S. Coulson, unpublished data). The changes in integrin protein levels occurred both within the infected cell and at the cell surface, which is indicative of modulation of protein expression rather than trafficking pathways. Changes in integrin protein levels also were generally reflected at the mRNA level, identifying transcriptional regulation as a key mechanism of modulation of integrin levels during rotavirus infection. An exception was β3 mRNA, which was unaltered by infection, even though αV mRNA expression was reduced. It is possible that αIIb (CD41), the other β3 partner, might be up-regulated by rotavirus infection or αV but not β3 may be targeted for regulation. The latter is supported by the down-regulation of αVβ5. The rotavirus-induced increases in α2 and β1 mRNA levels confirm the previous microarray finding of increases in mRNA expression of these integrin subunits in Caco-2 cells under similar conditions (19).

Many integrin-using and integrin-independent rotaviruses replicate to high titer in both Caco-2 and HT-29 cells (43, 66). It is noteworthy that αVβ3 is absent from HT-29 cells, indicating that αVβ3 is not necessary for RRV entry. Taken together, these data show that of the proposed integrin receptors for rotaviruses, α2β1 and αXβ2 are sufficient to mediate efficient attachment and entry into epithelial cells by integrin-using rotaviruses.

The extent of regulation of α2β1, β2, αVβ3, αVβ5, and α5β1 integrin expression following infection of Caco-2 cells by integrin-using rotaviruses RRV and Wa was indistinguishable from that of integrin-independent rotaviruses CRW-8 and 10/76. This demonstrates that the altered integrin expression induced following rotavirus infection was unrelated mechanistically to rotavirus usage of α2β1, αXβ2, and αVβ3 during cell attachment and entry. Rotavirus infection does not alter α2β1, β2, αVβ3, and α5β1 expression in surrounding uninfected cells, as uninfected cells within virus-infected cell cultures showed similar levels of these integrins to mock-infected cultures. Thus, virus spread to uninfected cells is not enhanced through integrin receptor up-regulation. These findings also indicate that the primary function of integrin regulation by rotaviruses is not to facilitate virus superinfection of the infected cells or a cellular defense mechanism to block virus release (19). However, in the case of the integrin-using rotaviruses, these functions might occur as secondary consequences of the integrin regulation. As altered Caco-2 cell expression of all integrins first occurred at the same time (8 h to 12 h) after infection and the levels of regulation of all integrins depended to similar extents on PI3K, it is likely that the mechanisms and signaling pathways involved in the regulation of each integrin are linked. Most trypsin-activated (infectious) RRV is internalized by MA104 cells within 3 to 5 min (41). The much later time after infection at which integrin expression was altered in our study suggests a requirement for rotavirus replication rather than signaling events induced following receptor engagement or entry, although these cannot be formally ruled out. This argument is further supported by the demonstration that Caco-2 cell exposure to inactivated RRV, which can enter cells but not replicate (61), does not induce integrin regulation.

PI3K inhibitors blocked rotavirus-induced regulation of integrin mRNA and protein expression in intestinal cells to a large extent, clearly identifying a specific role for PI3K. Involvement of the COX-2, p38, and MEK pathways was ruled out by the lack of effect of their inhibitors on rotavirus-induced modulation of integrin expression. The up-regulation of α3β1 integrin on enterocytes by bacterial endotoxin also depends on PI3K activation (56). Interestingly, induction of PI3K activity in Caco-2 cells with insulin did not alter integrin expression. Thus, although the PI3K pathway is crucial for rotavirus-induced changes in integrin expression, other rotavirus-dependent factors are also required.

Papillomaviruses and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reduce MHC class I levels on infected cells to escape detection and killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (2, 14). MHC class I expression was unaltered by rotavirus infection, showing that this immune evasion strategy is not used by rotaviruses. Although both rotaviruses and Ebola virus glycoprotein induce αvβ3 down-regulation, only Ebola virus also led to MHC class I down-regulation (62, 65, 67, 72). This suggests that these viruses reduce αVβ3 expression by different mechanisms, consistent with the rotavirus requirement for PI3K activity and the Ebola virus glycoprotein dependence on reduced activation of the MAPK ERK2 (72).

Rotavirus activated Akt in a PI3K-dependent process at 1 to 4 h after infection. PI3K activity inhibition during this time almost completely abolished α2β1 up-regulation in intestinal cells, whereas PI3K inhibition after this time had little effect. These findings demonstrate that rotavirus-induced PI3K activation is crucial for regulation of integrin expression. As integrin levels were unchanged in rotavirus-infected MA104 cells despite Akt activation, factors present only in intestinal cells appear to be required in addition to PI3K activity for rotavirus-induced integrin regulation. The 4- to 8-h delay between rotavirus-induced Akt activation and integrin protein regulation might reflect a more complex cellular process, rather than a direct effect of integrin transcriptional activation through the PI3K pathway. For example, integrin transcriptional regulation might depend on prior PI3K-dependent expression of particular proteins.

Virus activation of PI3K can occur through integrin recognition. Adenovirus stimulates PI3K activation within 5 min of virus binding to αV integrin receptors, which aids virion internalization (45). Papillomavirus-like particles induce PI3K activation by 10 min after α6β4 integrin engagement (25). Our work shows that rotavirus-induced PI3K activation is unlikely to occur via integrin receptor binding as the integrin-independent CRW-8 strain induced PI3K activation to a similar extent to RRV. Also, rotavirus-induced PI3K activation begins later than would be expected for receptor-induced activation. Although the timing could be consistent with activation during cell entry, this is unlikely. Inactivated rotavirus neither activated PI3K nor altered integrin expression, despite its reported ability to bind sialic acids and penetrate the cell membrane (61). Rotavirus replication transiently induces heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) at 2 to 7 h p.i. in Caco-2 but not MA104 cells (10, 70). Although the Hsp70 response can involve PI3K activation (57), PI3K involvement in Hsp70 induction by rotavirus seems unlikely as we found that Akt was phosphorylated during infection of both MA104 and Caco-2 cells. PI3K activation is utilized to decrease infection-induced apoptosis by influenza A virus, hepatitis C virus, flaviviruses, rubella virus, and EBV (15). The antiapoptotic effect of rotavirus-induced PI3K activation is worthy of further investigation.

Inhibition of PI3K activity reduced the α2β1-dependent adhesion of rotavirus-infected intestinal cells to collagen, consistent with their lower α2β1 expression under these conditions. In contrast, PI3K inhibition did not affect the number of rotavirus-infected MA104 cells bound mainly through α2β1 to collagen, in line with their unaltered α2β1 expression. These findings support the argument that rotavirus-induced α2β1 up-regulation is responsible for the increased collagen binding by rotavirus-infected intestinal cells. Infected intestinal cells adhered to collagen for longer times in the absence of PI3K inhibition. The extent of this adhesion increase was related to the rotavirus infectious yield, strongly suggesting that these are linked. During multiple rounds of infection, this could provide a distinct replicative advantage. In the human intestine, the major ligand for α2β1 is collagen (13). Therefore, it is likely that any rotavirus-induced up-regulation of enterocyte α2β1 expression in vivo would similarly extend cell adhesion and survival before infected cells are ultimately lost (9). In Caco-2 cells, αVβ3 down-regulation increases resistance to apoptosis, so the rotavirus-induced αVβ3 down-regulation we observed in these cells might be an additional mechanism that could prolong their viability (44).

From the studies presented here, PI3K-dependent integrin regulation appears to be used by rotavirus to increase the attachment and survival of infected intestinal cells and facilitate virus replication. These findings provide novel insights into rotavirus replicative strategies, the cell signaling cascades important for rotavirus replication, and the effects of rotavirus on intestinal cell interactions with the extracellular environment.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to A. Brooks and F. Carbone for their generous provision of reagents and J. Taylor for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by project grants (208900 and 350252) and research fellowships (299861 and 350253) awarded to B.S.C. from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC). S.J.T. holds an NHMRC RD Wright Fellowship (359207).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnaout, M. A., S. L. Goodman, and J. P. Xiong. 2002. Coming to grips with integrin binding to ligands. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14641-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashrafi, G. H., D. R. Brown, K. H. Fife, and M. S. Campo. 2006. Down-regulation of MHC class I is a property common to papillomavirus E5 proteins. Virus Res. 120208-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball, J. M., P. Tian, C. Q. Zeng, A. P. Morris, and M. K. Estes. 1996. Age-dependent diarrhea induced by a rotaviral nonstructural glycoprotein. Science 272101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basson, M. D. 1998. Role of integrins in enterocyte migration. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 25280-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basson, M. D., I. M. Modlin, and J. A. Madri. 1992. Human enterocyte (Caco-2) migration is modulated in vitro by extracellular matrix composition and epidermal growth factor. J. Clin. Investig. 9015-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaulieu, J. F. 1999. Integrins and human intestinal cell functions. Front. Biosci. 4D310-D321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop, R. F., G. P. Davidson, I. H. Holmes, and B. J. Ruck. 1973. Virus particles in epithelial cells of duodenal mucosa from children with acute non-bacterial gastroenteritis. Lancet ii1281-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaheta, R. A., E. Weich, D. Marian, J. Bereiter-Hahn, J. Jones, D. Jonas, M. Michaelis, H. W. Doerr, and J. Cinatl, Jr. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus infection alters PC3 prostate carcinoma cell adhesion to endothelial cells and extracellular matrix. Neoplasia 8807-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boshuizen, J. A., J. H. J. Reimerink, A. M. Korteland-van Male, V. J. J. van Ham, M. P. G. Koopmans, H. A. Büller, J. Dekker, and A. W. C. Einerhand. 2003. Changes in small intestinal homeostasis, morphology, and gene expression during rotavirus infection of infant mice. J. Virol. 7713005-13016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broquet, A. H., C. Lenoir, A. Gardet, C. Sapin, S. Chwetzoff, A.-M. Jouniaux, S. Lopez, G. Trugnan, M. Bachelet, and G. Thomas. 2007. Hsp70 negatively controls rotavirus protein bioavailability in Caco-2 cells infected by the rotavirus RF strain. J. Virol. 811297-1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caltabiano, S., W. T. Hum, G. J. Attwell, D. N. Gralnick, L. J. Budman, A. M. Cannistraci, and F. J. Bex. 1999. The integrin specificity of human recombinant osteopontin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 581567-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casola, A., R. P. Garofalo, S. E. Crawford, M. K. Estes, F. Mercurio, S. E. Crowe, and A. R. Brasier. 2002. Interleukin-8 gene regulation in intestinal epithelial cells infected with rotavirus: role of viral-induced IkB kinase activation. Virology 2988-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choy, M. Y., P. I. Richman, M. A. Horton, and T. T. MacDonald. 1990. Expression of the VLA family of integrins in human intestine. J. Pathol. 16035-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins, K. L., B. K. Chen, S. A. Kalams, B. D. Walker, and D. Baltimore. 1998. HIV-1 Nef protein protects infected primary cells against killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature 391397-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooray, S. 2004. The pivotal role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt signal transduction in virus survival. J. Gen. Virol. 851065-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coulson, B. S. 1993. Typing of human rotavirus VP4 by an enzyme immunoassay using monoclonal antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coulson, B. S., S. L. Londrigan, and D. J. Lee. 1997. Rotavirus contains integrin ligand sequences and a disintegrin-like domain that are implicated in virus entry into cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 945389-5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coulson, B. S., L. E. Unicomb, G. A. Pitson, and R. F. Bishop. 1987. Simple and specific enzyme immunoassay using monoclonal antibodies for serotyping human rotaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25509-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuadras, M. A., D. A. Feigelstock, S. An, and H. B. Greenberg. 2002. Gene expression pattern in Caco-2 cells following rotavirus infection. J. Virol. 764467-4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danen, E. H., and A. Sonnenberg. 2003. Integrins in regulation of tissue development and function. J. Pathol. 201632-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Biase, A. M., G. Petrone, M. P. Conte, L. Seganti, M. G. Ammendolia, A. Tinari, F. Iosi, M. Marchetti, and F. Superti. 2000. Infection of human enterocyte-like cells with rotavirus enhances invasiveness of Yersinia enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 49897-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksson, M., L. Arminen, M. L. Karjalainen-Lindsberg, and S. Leppa. 2005. AP-1 regulates α2β1 integrin expression by ERK-dependent signals during megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 304175-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feire, A. L., H. Koss, and T. Compton. 2004. Cellular integrins function as entry receptors for human cytomegalovirus via a highly conserved disintegrin-like domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10115470-15475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferri, N., K. J. Garton, and E. W. Raines. 2003. An NF-κB-dependent transcriptional program is required for collagen remodeling by human smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27819757-19764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fothergill, T., and N. A. McMillan. 2006. Papillomavirus virus-like particles activate the PI3-kinase pathway via α6β4 integrin upon binding. Virology 352319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franke, T. F., S. I. Yang, T. O. Chan, K. Datta, A. Kazlauskas, D. K. Morrison, D. R. Kaplan, and P. N. Tsichlis. 1995. The protein kinase encoded by the Akt proto-oncogene is a target of the PDGF-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell 81727-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavrilovskaya, I. N., T. Peresleni, E. Geimonen, and E. R. Mackow. 2002. Pathogenic hantaviruses selectively inhibit β3 integrin directed endothelial cell migration. Arch. Virol. 1471913-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham, K. L., F. E. Fleming, P. Halasz, M. J. Hewish, H. S. Nagesha, I. H. Holmes, Y. Takada, and B. S. Coulson. 2005. Rotaviruses interact with α4β7 and α4β1 integrins by binding the same integrin domains as natural ligands. J. Gen. Virol. 863397-3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham, K. L., P. Halasz, Y. Tan, M. J. Hewish, Y. Takada, E. R. Mackow, M. K. Robinson, and B. S. Coulson. 2003. Integrin-using rotaviruses bind α2β1 integrin α2 I domain via VP4 DGE sequence and recognize αXβ2 and αVβ3 by using VP7 during cell entry. J. Virol. 779969-9978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham, K. L., W. Zeng, Y. Takada, D. C. Jackson, and B. S. Coulson. 2004. Effects on rotavirus cell binding and infection of monomeric and polymeric peptides containing α2β1 and αxβ2 integrin ligand sequences. J. Virol. 7811786-11797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groene, W. S., and R. D. Shaw. 1992. Psoralen preparation of antigenically intact noninfectious rotavirus particles. J. Virol. Methods 3893-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guerrero, C. A., E. Mendez, S. Zarate, P. Isa, S. Lopez, and C. F. Arias. 2000. Integrin αvβ3 mediates rotavirus cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9714644-14649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haier, J., M. Nasralla, and G. L. Nicolson. 1999. Different adhesion properties of highly and poorly metastatic HT-29 colon carcinoma cells with extracellular matrix components: role of integrin expression and cytoskeletal components. Br. J. Cancer. 801867-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hewish, M. J., Y. Takada, and B. S. Coulson. 2000. Integrins α2β1 and α4β1 can mediate SA11 rotavirus attachment and entry into cells. J. Virol. 74228-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holloway, G., and B. S. Coulson. 2006. Rotavirus activates JNK and p38 signaling pathways in intestinal cells, leading to AP-1-driven transcriptional responses and enhanced virus replication. J. Virol. 8010624-10633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Honore, S., V. Pichard, C. Penel, V. Rigot, C. Prevot, J. Marvaldi, C. Briand, and J. B. Rognoni. 2000. Outside-in regulation of integrin clustering processes by ECM components per se and their involvement in actin cytoskeleton organization in a colon adenocarcinoma cell line. Histochem. Cell Biol. 114323-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang, S., D. Stupack, A. Liu, D. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 2000. Cell growth and matrix invasion of EBV-immortalized human B lymphocytes is regulated by expression of αv integrins. Oncogene 191915-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hynes, R. O. 2002. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110673-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jafri, M., B. Donnelly, M. McNeal, R. Ward, and G. Tiao. 2007. MAPK signaling contributes to rotaviral-induced cholangiocyte injury and viral replication. Surgery 142192-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jolly, C. L., B. M. Beisner, and I. H. Holmes. 2000. Rotavirus infection of MA104 cells is inhibited by Ricinus lectin and separately expressed single binding domains. Virology 27589-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaljot, K. T., R. D. Shaw, D. H. Rubin, and H. B. Greenberg. 1988. Infectious rotavirus enters cells by direct cell membrane penetration, not by endocytosis. J. Virol. 621136-1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kemperman, H., Y. M. Wijnands, and E. Roos. 1997. αV integrins on HT-29 colon carcinoma cells: adhesion to fibronectin is mediated solely by small amounts of αVβ6, and αVβ5 is codistributed with actin fibers. Exp. Cell Res. 234156-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitamoto, N., R. F. Ramig, D. O. Matson, and M. K. Estes. 1991. Comparative growth of different rotavirus strains in differentiated cells (MA104, HepG2, and CaCo-2). Virology 184729-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kozlova, N. I., G. E. Morozevich, A. N. Chubukina, and A. E. Berman. 2001. Integrin αvβ3 promotes anchorage-dependent apoptosis in human intestinal carcinoma cells. Oncogene 204710-4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li, E., D. Stupack, R. Klemke, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 1998. Adenovirus endocytosis via αv integrins requires phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase. J. Virol. 722055-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Londrigan, S. L., K. L. Graham, Y. Takada, P. Halasz, and B. S. Coulson. 2003. Monkey rotavirus binding to α2β1 integrin requires the α2 I domain and is facilitated by the homologous β1 subunit. J. Virol. 779486-9501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Londrigan, S. L., M. J. Hewish, M. J. Thomson, G. M. Sanders, H. Mustafa, and B. S. Coulson. 2000. Growth of rotaviruses in continuous human and monkey cell lines that vary in their expression of integrins. J. Gen. Virol. 812203-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lundgren, O., A. T. Peregrin, K. Persson, S. Kordasti, I. Uhnoo, and L. Svensson. 2000. Role of the enteric nervous system in the fluid and electrolyte secretion of rotavirus diarrhea. Science 287491-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lussier, C., N. Basora, Y. Bouatrouss, and J. F. Beaulieu. 2000. Integrins as mediators of epithelial cell-matrix interactions in the human small intestinal mucosa. Microsc. Res. Tech. 51169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Massoumi, R., C. K. Nielsen, D. Azemovic, and A. Sjolander. 2003. Leukotriene D4-induced adhesion of Caco-2 cells is mediated by prostaglandin E2 and upregulation of α2β1-integrin. Exp. Cell Res. 289342-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagesha, H. S., L. E. Brown, and I. H. Holmes. 1989. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against three serotypes of porcine rotavirus. J. Virol. 633545-3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okamoto, M., T. Hayashi, S. Kono, G. Inoue, M. Kubota, H. Kuzuya, and H. Imura. 1993. Specific activity of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is increased by insulin stimulation. Biochem. J. 290327-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Osborne, M. P., S. J. Haddon, A. J. Spencer, J. Collins, W. G. Starkey, T. S. Wallis, G. J. Clarke, K. J. Worton, D. C. Candy, and J. Stephen. 1988. An electron microscopic investigation of time-related changes in the intestine of neonatal mice infected with murine rotavirus. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 7236-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pegtel, D. M., A. Subramanian, T.-S. Sheen, C.-H. Tsai, T. R. Golub, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 2005. Epstein-Barr-virus-encoded LMP2A induces primary epithelial cell migration and invasion: possible role in nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis. J. Virol. 7915430-15442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plow, E. F., T. A. Haas, L. Zhang, J. Loftus, and J. W. Smith. 2000. Ligand binding to integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 27521785-21788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qureshi, F. G., C. Leaphart, S. Cetin, J. Li, A. Grishin, S. Watkins, H. R. Ford, and D. J. Hackam. 2005. Increased expression and function of integrins in enterocytes by endotoxin impairs epithelial restitution. Gastroenterology 1281012-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rafiee, P., M. E. Theriot, V. M. Nelson, J. Heidemann, Y. Kanaa, S. A. Horowitz, A. Rogaczewski, C. P. Johnson, I. Ali, R. Shaker, and D. G. Binion. 2006. Human esophageal microvascular endothelial cells respond to acidic pH stress by PI3K/AKT and p38 MAPK-regulated induction of Hsp70 and Hsp27. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291C931-C945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riikonen, T., J. Westermarck, L. Koivisto, A. Broberg, V. M. Kahari, and J. Heino. 1995. Integrin α2β1 is a positive regulator of collagenase (MMP-1) and collagen α1(I) gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 27013548-13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt, R., M. Streit, R. Kaiser, F. Herzberg, M. Schirner, K. Schramm, C. Kaufmann, M. Henneken, M. Schafer-Korting, E. Thiel, and E. D. Kreuser. 1998. De novo expression of the α5β1-fibronectin receptor in HT29 colon-cancer cells reduces activity of C-SRC. Increase of C-SRC activity by attachment on fibronectin. Int. J. Cancer. 7691-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shahgasempour, S., S. B. Woodroffe, G. Sullivan-Tailyour, and H. M. Garnett. 1997. Alteration in the expression of endothelial cell integrin receptors α5β1 and α2β1 and α6β1 after in vitro infection with a clinical isolate of human cytomegalovirus. Arch. Virol. 142125-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shaw, R. D., and S. J. Hempson. 1996. Replication as a determinant of the intestinal response to rotavirus. J. Infect. Dis. 1741328-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]