Abstract

Cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL) play a major role in controlling human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. To evade immune pressure, HIV-1 is selected at targeted CTL epitopes, which may consequentially alter viral replication fitness. In our longitudinal investigations of the interplay between T-cell immunity and viral evolution following acute HIV-1 infection, we observed in a treatment-naïve patient the emergence of highly avid, gamma interferon-secreting, CD8+ CTL recognizing an HLA-Cw*0102-restricted epitope, NSPTRREL (NL8). This epitope lies in the p6Pol protein, located in the transframe region of the Gag-Pol polyprotein. Over the course of infection, an unusual viral escape mutation arose within the p6Pol epitope through insertion of a 3-amino-acid repeat, NSPT(SPT)RREL, with a concomitant insertion in the p6Gag late domain, PTAPP(APP). Interestingly, this p6Pol insertion mutation is often selected in viruses with the emergence of antiretroviral drug resistance, while the p6Gag late-domain PTAPP motif binds Tsg101 to permit viral budding. These results are the first to demonstrate viral evasion of immune pressure by amino acid insertions. Moreover, this escape mutation represents a novel mechanism whereby HIV-1 can alter its sequence within both the Gag and Pol proteins with potential functional consequences for viral replication and budding.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) undergoes remarkable sequence evolution in humans during the course of infection. Viral evolution is driven largely by selective immune evasion (1, 16, 24, 33) and drug resistance mutations in combination with reversions (2, 12, 22, 23, 43) to restore replication fitness (25). HIV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) are major contributors of immune effector activities against HIV-1. Typically, CTL are induced during acute HIV-1 infection and broaden in specificity over time (7, 8, 47). To date, hundreds of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-restricted CTL epitopes have been identified, and each of the major HIV-1 proteins contains known epitopes (www.hiv.lanl.gov). The antiviral activities of CD8+ T cells can exert selective immune pressure, which can lead to viral escape mutations within the epitopes recognized during acute infection (6, 8, 47) and over the course of chronic infection (20, 37). Most often, this occurs by substitution of an amino acid at a position in the epitope critical for interaction with its cognate MHC or T-cell receptor, but it can also involve changes in flanking residues (11, 46). The known epitopes may differ in their abilities to stimulate highly avid CTL among HIV-positive individuals, gain immunodominance, and acquire escape mutations (11, 14, 22, 24, 32, 47). The properties of the epitopes that account for these differences merit further understanding, since they potentially govern viral selection and replication fitness within the host and among populations at risk.

Reverse transcriptase and protease inhibitors have been the cornerstone of antiretroviral therapy over the past decade. As resistance to these agents has developed, distinct viral genotypes conferring resistance have been identified, particularly with advances in resistance monitoring (reviewed in reference 42). Parallel investigations of the host immune response to HIV-1 infection indicate that HIV-specific CD8+ CTL can recognize epitopes within the active sites of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and protease targeted by these therapeutic agents, suggesting that these alterations may influence viral replication capacity (38). Recent studies have characterized CTL epitopes directed to drug resistance mutations (26), and some drug resistance mutations have been shown to sustain or enhance CTL recognition (31).

To gain insight into immune selection of HIV-1 and its impact on viral replication and diversity, we assessed and reported detailed T-cell responses for 21 Seattle, WA, patients with newly diagnosed primary infection (7). Forty-one unique HLA class I-restricted epitopes were identified (7), and the epitope specificities broadened over the course of infection. The concomitant immune and viral sequence analyses of patient PIC1362, who enrolled during acute infection and elected not to receive antiretroviral therapy during the first 4 years of infection, provided particular insight (8, 24, 25). Escape mutations in the initially recognized HIV-1 Tat, Vpr, and Env epitopes occurred in PIC1362 within weeks of infection (8, 24, 25). Subsequently, as we report here, an unusual escape mutation emerged, corresponding to a 3-amino-acid insertion in the p6Pol protein. The same insertion had previously been shown to occur during the use of nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI). Thus, HIV-1 may be selected by the same mechanism through antiretroviral therapy or immune pressure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary infection study.

The study participant, PIC1362, is enrolled in a longitudinal natural history study at the University of Washington Primary Infection Clinic. Methods for diagnosis of HIV-1 infection, clinical and virological monitoring, and HLA typing have been reported previously (7, 40). The University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center institutional review boards approved the study, and all subjects provided written informed consent for participation in the study. The functional avidities of HIV-1-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses were evaluated using previously cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in a gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay as described previously (7). Cells were stimulated with 2 μg/ml (unless otherwise indicated) of overlapping 15-mer peptides, alone or in pools, or defined peptides (8- to 11-mers). These peptides either were synthesized by the Biotechnology Shared Resources Facility at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center or were kindly supplied by the NIH AIDS Reference and Reagents Program. Class I MHC restriction analysis was performed as previously described (7) by using autologous Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (B-LCL) and donor B-LCL with partially matched alleles as antigen-presenting cells in the ELISPOT assay. Functional avidity was correlated with the calculated EC50, defined as the effective peptide concentration eliciting 50% of the peak IFN-γ response in the ELISPOT assay. A logistic curve-fitting function (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) was used to plot dose-response curves and determine EC50 values.

51Cr release cytolytic assay.

HIV-1-specific cytolytic activities were determined after stimulation with peptides in a chromium release assay (32). Briefly, cryopreserved PBMC were thawed and cultured overnight at 37°C under 5% CO2. B-LCL (3,000 cells) were first incubated with no peptide or 2 μg/ml specific peptide for 90 min at 37°C under 5% CO2, then labeled with 50 μCi/ml sodium [51Cr]chromate (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA), and finally washed with medium. PBMC were depleted of CD4+ cells using anti-CD4 antibody-coated micromagnetic beads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA) and then mixed with 51Cr-labeled B-LCL at various effector-to-target cell (E:T) ratios. The release of 51Cr in the culture supernatant was determined after 5 h of incubation. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as: (mean experimental 51Cr release − mean spontaneous 51Cr release) × 100/(mean total 51Cr release − mean spontaneous 51Cr release).

Sequence analysis of cell-associated virus.

Total cellular RNA was purified from 1 to 2 million cryopreserved PBMC using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). HIV-1 sequences were amplified by standard reverse transcription-PCR using Superscript II reverse transcriptase and Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cDNA was amplified by PCR over 35 cycles (30 s at 94°C, 15 s at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C). The p6Pol epitope region was amplified using the forward primer 5′-AAAGATTGTACTGAGAGACAGGCTAA (HIV-1 HXB2 positions 2059 to 2084) and two reverse primers, 5′-AGGGAGTTGTTGTCCCTTCC (HIV-1 HXB2 positions 2206 to 2187) and 5′-TATTGTGACGAGGGGTCGTT (HIV-1 HXB2 positions 2291 to 2272). The PCR products were cloned into the pCR4 TOPO TA vector according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). Plasmids from individual clones were isolated and sequenced using T7 forward and T3 reverse primers with ABI Prism BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Additional sequences were obtained from plasma viral RNA at days 8 and 826 after infection (24). Computational analysis of viral sequences was performed using the BLAST software package from NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) and the Los Alamos HIV database (www://hiv.lanl.gov).

RESULTS

Recognition of the Cw*0102-restricted p6Pol epitope NL8.

PIC1362 enrolled 8 days after the onset of signs and symptoms consistent with an acute retroviral syndrome. At enrollment, his plasma contained 8.24 × 106 copies/ml of HIV-1 RNA (Table 1) but lacked detectable serum HIV-1-specific antibodies. By day 22, he developed HIV-1-specific antibodies detectable by an HIV-1 enzyme immunoassay, indicating seroconversion (8). In 22 subsequent follow-up visits over 4 years, the patient declined antiretroviral therapy. He remained clinically healthy and maintained normal CD4+ T-cell counts (median, 1,047 cells/μl) despite a viral load fluctuating between 17,036 to 95,388 copies/ml after the first 3 weeks of infection (Table 1) (8). HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells, recognizing the HLA Cw*12-, B*51-, and B*18-restricted Tat, Vpr, and Env epitopes, emerged during acute infection in concert with a reduction in acute viremia (8, 24). Viral escape mutations arose soon thereafter within these epitopes by amino acid substitutions within presumed anchor residues (8, 24). The HIV-1-specific CD8+ T-cell responses then shifted to recognition of other epitopes after 2 months of infection (8, 24). A new p6Pol epitope was revealed by screening of PBMC obtained at day 826 for ex vivo IFN-γ secretion in an ELISPOT assay with peptide pools spanning all HIV-1 coding regions, including a 15-mer Pol peptide pool spanning the transframe region of Gag-Pol (Fig. 1). The minimal epitopic peptide NSPTRREL (NL8) (see below) was recognized upon repeat analysis of previously cryopreserved PBMC at the limit of detection by the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay on day 34 but was not clearly positive until day 680 (Table 1). At peak p6Pol responses on days 826 and 829, the patient maintained a CD4+ T-cell count of 1,211 cells/μl, a viral load of 95,388 RNA copies/ml, and a total HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell response of >5,000 IFN-γ spot-forming cells (SFC)/106 PBMC. The dominant responses targeted the B*18-restricted Nef YF9 (YPLTFGWCF), A*25-restricted Gag EW10 (ETINEEAAEW), and Cw*01-restricted Gag VL8 (VIPMFSAL) epitopes, each exceeding 1,000 IFN-γ SFC/106 PBMC (8, 24; also data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Longitudinal analysis of the Pol NL8-specific CD8+ T-cell response and the viral epitope sequences

| Days after infection | Plasma viral load (copies/ml) | NL8-specific response (SFC/106 PBMC)a | Frequency of the following epitope sequence:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSPTRREL | NSPTSPTRREL | NSPTSPTIREL | NSPTSPTRGEL | |||

| 8 | 8,240,000 | ND | 9/9b | 0/9b | ||

| 34 | 57 | |||||

| 51 | 78,000 | 0 | ||||

| 155 | 23,116 | 25 | ||||

| 307 | 0 | |||||

| 491 | 74,580 | ND | ||||

| 496 | 8 | 17/17 | 0/17 | |||

| 680 | 123 | |||||

| 826 | 95,388 | 450 | 15/23 | 7/23 | 1/23 | |

| 6/10b | 4/10b | |||||

| 829 | 457 | |||||

| 1,035 | 17,036 | 165 | 2/15 | 12/15 | 1/15 | |

| 1,144 | 53,178 | ND | 1/14 | 13/14 | ||

| 1,500 | 29,290 | 0 | 4/18 | 12/18 | 2/18 | |

NL8-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells determined by the ELISPOT assay. The SFC frequencies in the no-peptide control wells were subtracted from the NL8-specific responses. A response of ≥50 IFN-γ-secreting SFC/106 PBMC was considered positive. ND, not determined. At day 1,035 postinfection, results were obtained by testing the peptide pool containing all 15-mers listed in Fig. 1.

Sequence generated from plasma viral RNA. All other sequences were from PBMC-associated RNA.

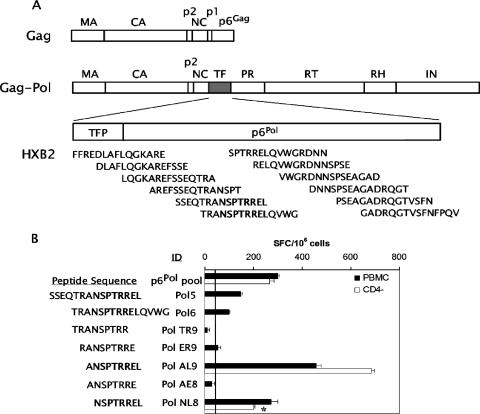

FIG. 1.

Defining the T-cell determinant within HIV-1 p6Pol. (A) Schematic representation of HIV-1 Gag, the Gag-Pol polyprotein, and the overlapping 15-amino-acid peptides spanning the transframe region (TF) used for evaluation of CD8+ T-cell responses. The protease cleavage products matrix (MA), capsid (CA), p2, nucleocapsid (NC), TF, protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), RNase H (RH), and integrase (IN) are indicated. TF includes the transframe octapeptide (TFP) and p6Pol. The sequences shown correspond to reference isolate HIV-1 HXB2. (B) Previously cryopreserved PBMC (solid bars) or CD4-depleted PBMC (CD4−) (open bars) were assessed for IFN-γ secretion by an ELISPOT assay following overnight stimulation with the Pol peptide pool or individual peptides as shown. Results are expressed as IFN-γ SFC/106 cells (mean ± standard error) and indicate the frequencies of spots found in the experimental wells (peptide-stimulated cells) minus those in the negative-control wells (non-peptide-stimulated cells). The vertical line marks the threshold for a positive response, 50 SFC/106 cells. Cells for this assay were collected at 826 days after infection, except for the CD4-depleted PBMC stimulated with Pol NL8 (*), which were derived 680 days after infection.

Characterization of the Pol NL8 response.

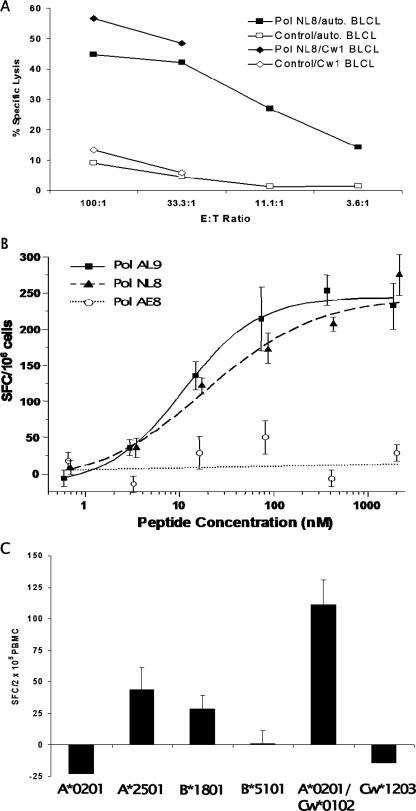

The IFN-γ response to the p6Pol peptide pool was fine mapped using individual 15-mers and truncated peptides (Fig. 1A). Overlapping 15-mer peptides 5 and 6 elicited positive responses in the ELISPOT assay (Fig. 1B). The Pol NL8 peptide, NSPTRREL, was the smallest peptide inducing an IFN-γ response from cells obtained at day 826; this response was also mediated by anti-CD4 antibody-depleted PBMC, indicating that it was a CD8+ T-cell response (Fig. 1B). Pol NL8 is located in p6Pol, a 48-amino-acid polypeptide encoded by the transframe region of Gag-Pol, downstream of the ribosomal frameshift site and upstream of the viral protease (Fig. 1A). To determine if the Pol NL8-specific CD8+ T cells were capable of cytolytic activity, we performed a 51Cr release assay using peptide-pulsed B-LCL as targets and CD4-depleted PBMC as effectors (Fig. 2A). Significant lysis of the Pol NL8-pulsed autologous B-LCL occurred at E:T ratios from 3.6:1 to 100:1. We next determined the functional avidity of the IFN-γ response by stimulation with the serially diluted peptide Pol AL9 (ANSPTRREL), AE8 (ANSPTRRE), or NL8 (NSPTRREL) (Fig. 2B). The estimated peptide concentrations at 50% maximal responses (EC50) were similar for the two Pol peptides AL9 (11 ± 3.31 nM) and NL8 (13 ± 3.69 nM). Thus, the addition of alanine to the N terminus of the NL8 epitopic peptide appeared neutral for in vitro binding interactions with MHC class I and the T-cell receptor. These EC50 values were significantly lower (>10-fold) than that of the Cw*12-restricted Tat peptide CCFHCQVC (212 nM) and within a threefold range of those of the B*51-restricted Vpr epitope EAVRHFPRI (30 nM) and the B*18-restricted Env epitope YETEVWHNVW (12 nM), each of which showed rapid CTL escape (7, 8, 24) during acute HIV-1 infection for this patient. To assess the MHC class I restriction of the Pol NL8 epitope, we tested partially matched B-LCL for their abilities to present the NL8 peptide to CD8+ T cells in IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (Fig. 2C). The greatest IFN-γ SFC frequencies were observed when CD8+ T cells were stimulated with NL8-pulsed B-LCL expressing the HLA-A*0201 and Cw*0102 alleles, whereas B-LCL expressing the A*0201 allele alone did not stimulate a response. Thus, Cw*01, and specifically Cw*0102, is the restricting allele. This MHC restriction is further supported by alignment of the Pol NL8 epitope with other known Cw*0102 epitopes; all share the C-terminal leucine anchor residue and a proline at position 3 (3, 29). Cw*01-restricted cytolysis was also observed using partially matched allogeneic B-LCL (Fig. 2A). Thus, NL8-specific CD8+ T cells were both cytolytic and capable of secreting IFN-γ when the epitope was presented by HLA-Cw*0102-expressing cells. Among all Cw*01-restricted epitopes defined in chronic infection, the NL8 EC50 was lower than those of the Gag VL8 (23 nM), Env YL9 (YSPLSLQTL) (82 nM), and Env YL10 (YCAPAGFAIL) (66 nM) epitopes and significantly lower than that of the Vpu HL9 (HAPWDVNDL) epitope (270 nM) (7, 8, 24).

FIG. 2.

Further characterization of the p6Pol NL8-specific T cells. (A) Cytolysis of B-LCL pulsed with the Pol NL8 peptide as determined by a 51Cr release assay. Autologous (squares) or allogeneic (partially matched for the Cw*0102 allele) (diamonds) B-LCL were pulsed with no peptide (open symbols) or the Pol NL8 peptide (solid symbols), and PBMC from patient 1362 were used as effector cells. Percent specific lysis is shown at the indicated E:T ratios. (B) Determination of the minimal epitope by peptide titration. PBMC were tested for IFN-γ secretion by an ELISPOT assay using the serially diluted peptides Pol AL9 (solid squares), NL8 (solid triangles), and AE8 (open circles). The frequency of IFN-γ-secreting cells is expressed as in Fig. 1B. (C) Determination of the MHC class I restriction of the Pol NL8 epitope by an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. Autologous PBMC were stimulated with Pol NL8-pulsed B-LCL from various donors with partially matched HLA alleles. The matching MHC class I alleles of six donor B-LCL are indicated along the x axis. The y axis indicates IFN-γ SFC frequencies (means ± standard errors) after subtraction of the frequencies from the negative control.

Escape mutation within the NL8 epitope.

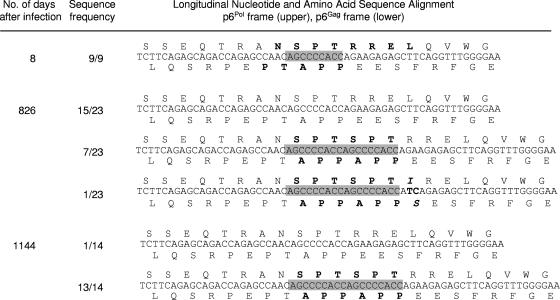

To examine the impact of the virus-specific T cells on viral sequence evolution, we compared T-cell responses recognizing Pol NL8 with the viral epitope sequences present over the first 4 years of infection. The Pol NL8-specific CTL response emerged between 496 and 680 days, peaking between 680 and 1,035 days after infection (Table 1). Prior to day 680, all viral sequences were NSPTRREL. By day 826, 30% (7/23) of the cell-associated viral RNA sequences and 40% (4/10) of the plasma viral RNA sequences contained a 9-nucleotide repeat (AGCCCCACC), producing 3-amino-acid insertions in two reading frames: (i) SPT within the NL8 epitope, resulting in N-SPT-SPT-RREL (designated NL11) in the p6Pol reading frame, and (ii) APP, resulting in PTAPP-APP, in the p6Gag reading frame (Table 1; Fig. 3). The insertion in the p6Pol reading frame changed the NL8 minimal epitope to TSPTRREL (TL8) (Table 1; Fig. 3). At 826 days, a low-frequency SPT insertion variant also emerged with an additional change within the p6Pol epitope, TSPTIREL (Table 1; Fig. 3). As the insertion frequency peaked and became dominant, the Pol NL8-specific CTL response waned by day 1,035 (165 SFC/106 PBMC) and was no longer detected at day 1,500 (Table 1). The SPT insertion in the Pol NL8 epitope thus appears to be under directed selection, with its emergence and accumulation paralleling the CTL response to the Pol NL8 epitope. The extent of selection within the NL8 epitope has been detected and assessed by longitudinal whole HIV-1 genome sequencing (24; also data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Sequence analysis of the CTL escape insertion, demonstrating its effects on both the p6Pol (SPT insertion) and p6Gag (APP insertion) reading frames. Highlighted are the 9-nucleotide sequence corresponding to the SPT amino acid sequence and the duplicated sequence at 829 and 1,144 days postinfection.

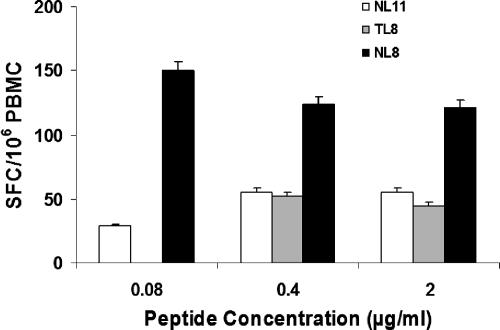

To determine whether the insertion mutation led to escape from the Pol NL8-specific T-cell response, we synthesized and tested the mutated forms of NL8 for recognition in IFN-γ ELISPOT assays. T cells from day 680 recognized the Pol NL8 peptide; however, neither of the mutant peptides NL11 and TL8, used at concentrations of 0.08, 0.4, and 2 μg/ml, stimulated significant numbers of IFN-γ-secreting T cells (Fig. 4). The combined results from the analyses of the peptide dose responses, the longitudinal responses to the Pol NL8 epitope, and the viral epitope sequences indicate that the 3-amino-acid insertion mediated viral escape as the Pol NL8-specific response developed over time. NL8-specific T cells then declined, likely due to loss of NL8 expression on the antigen-presenting cells.

FIG. 4.

Lack of recognition of the p6Pol mutant peptides. PBMC from day 680 after infection were assessed for IFN-γ secretion by an ELISPOT assay following stimulation with the following serially diluted peptides: NL8, TL8, and NL11. Results are expressed as IFN-γ SFC/106 PBMC (means ± standard errors) after subtraction of the no-peptide control.

DISCUSSION

This study characterizes a new MHC class I CTL epitope in HIV-1 p6Pol, Pol NL8 (NSPTRREL), and viral escape through a novel mechanism: insertion of amino acids, which occurred as a result of nucleotide duplication. Investigations of T-cell immunity in HIV-1 infection have commonly overlooked responses in the transframe region, from which p6Pol derives. The Pol NL8 epitope is the first and only epitope in the transframe region to appear in the HIV immunology database (www.hiv.lanl.gov). One of the cleavage products of the Gag-Pol polyprotein located just downstream from the ribosomal frameshift site (18), p6Pol is present in mature viral particles and affects protease activity (34, 36, 45, 48). The Pol NL8 epitope corresponds to the consensus sequence for B clade isolates and is generally conserved in other clades, with the major difference in clade A, C, and D isolates being an arginine-to-serine change at the fifth position (http:www.hiv.lanl.gov).

The Pol NL8 epitope was one of at least five Cw*01-restricted epitopes recognized by CTL of this Caucasian patient (24). Of note, the HLA Cw*01 allele is more common in the Australasian Aboriginal (25.1%) and Asian (9.29%) populations than in Caucasians (4.07%) (29). Interestingly, three of the other four Cw*01-restricted epitopes (Env YL9, Env YL10, and Vpu HL9 [but not Gag VL8]) also underwent escape mutations following CTL recognition (24, 25). This patient's other HLA-C allele, Cw*12, also presented an immunodominant Tat-specific epitope during acute infection (7, 8, 24; unpublished data). By contrast, this individual has the HLA A*0201 allele, occurring at a high population frequency among Caucasians (28), but only one A*0201-restricted epitope was identified over the course of infection (24). These findings highlight the potential importance of HLA-C alleles in presenting HIV-1 CTL epitopes, especially since Nef-mediated down-regulation of class I molecules is less efficient on C alleles than on A and B alleles (9, 21).

As the CTL response to the Pol NL8 epitope peaked, viral escape ensued as a result of a 9-nucleotide insertion, translating into a 3-amino-acid SPT repeat within the epitope that occurred at a frequency of 93% on day 1,144 after infection. Due to the overlap of Gag and Gag-Pol in the NL8 epitope region, immune escape also led to an insertion in p6Gag, corresponding to a repeat of the amino acids APP after the critical proline-rich PTAPP motif of p6Gag. While natural variation in p6Pol/p6Gag has been described previously (4), to our knowledge this is the first example of an HIV-1 CTL escape mutation associated with amino acid insertions that can have a functional impact on two proteins.

Interestingly, the same SPT/APP insertion in p6Pol/p6Gag has been demonstrated in 5.4% (35) of HIV isolates from treatment-naïve HIV patients. In HIV patients treated with NRTI, the insertion frequency was 21.2% (35) to 36.4% (17) of viral sequences analyzed in these studies. Various effects of drug resistance mutations on T-cell immunity in HIV-1 infection have been reported (19, 39, 41), but none on the Pol NL8 epitope and by the STP/APP insertion. When Peters and colleagues inserted the coding sequences of the SPT/APP repeat into HIV-1 NL4-3, the resulting virus exhibited increased resistance to NRTI and increased reverse transcriptase content in the virion, and activity was elevated in the mutant virus, but there was a delay in Gag cleavage and viral particle release (35). Thus, this single mutation may contribute to both immune evasion, as shown here for an untreated patient, and antiretroviral drug resistance. Mechanistically, the SPT/APP site may be a hot spot for template-primer misalignment during reverse transcriptase-mediated reactions (5). Of note, however, PIC1362 developed the SPT/APP insertion without ever receiving antiviral treatment, and the repeat has been noted previously in viral isolates from antiretroviral-treatment-naïve patients (17), which we speculate may have resulted from CTL selection.

The insertional mutation created a duplication of APP after the proline-rich PTAPP motif within the p6Gag late domain. Interestingly, PTAPP is the binding site of Tsg101, the cellular protein that is a putative ubiquitin regulator involved in intracellular trafficking of plasma membrane-associated proteins (30, 44). Presumably, this interaction allows HIV to recruit Tsg101 for efficient budding of the viral particle (30; reviewed in reference 15). Gag p6 Tsg101 binding site duplications have been detected in maternal-infect HIV infection cohorts, with 10/103 (9.7%) of mother-infant sets containing the PTAPP(APP) duplication (10). Duplication of PTAPP motifs, as well as mutagenesis of PTAPP motifs and specific flanking Lys residues, has been shown to significantly alter Tsg101 binding (44), either enhancing or decreasing the interaction and thus the rate at which virus particles are released from the membrane. In the context of viral fitness, the effect on virus particle trafficking, if any, of a 3-amino-acid insertion resulting from CTL selection in a different reading frame would be a unique mechanism and merits further study. Unfortunately, defining the effects of single escape mutations on the viral load in this patient is not feasible, because multiple CTL epitopes were recognized over the same period and the viral load fluctuated between 17,036 and 95,388 copies/ml, delineating the viral load set point.

In conclusion, our findings of CTL-mediated selection within the same Pol sequence where antiretroviral drug selection has previously been defined for treated patients attest to the remarkable plasticity of HIV. Whether this subsequent change in the Gag protein may improve viral fitness through more efficient viral budding remains unclear, but the presence of these insertions in diverse HIV-1 subtypes, particularly in clade C viruses (27), may play some functional role in replication. Finally, the identification of the Cw*0102-restricted Pol NL8 epitope in the transframe region demonstrates that host T-cell immunity has the potential to target all HIV proteins, effecting broad-based suppression of viral replication, which may lead to selection on HIV-1 providing several mechanisms of escape, including amino acid insertions within CTL epitopes and other functional reading frames.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient; Janine Maenza and Claire Stevens for support in the clinic; Lawrence Corey and his laboratory for performing the viral load measurements; Indira Genowati and Hong Zhao for excellent technical assistance; and Phyllis Stegall for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by PHS grants from the NIH (AI-41535, AI-48017, and AI-57005) and by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (AI-27757).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, T. M., M. Altfeld, S. C. Geer, E. T. Kalife, C. Moore, K. M. O'Sullivan, I. Desouza, M. E. Feeney, R. L. Eldridge, E. L. Maier, D. E. Kaufmann, M. P. Lahaie, L. Reyor, G. Tanzi, M. N. Johnston, C. Brander, R. Draenert, J. K. Rockstroh, H. Jessen, E. S. Rosenberg, S. A. Mallal, and B. D. Walker. 2005. Selective escape from CD8+ T-cell responses represents a major driving force of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) sequence diversity and reveals constraints on HIV-1 evolution. J. Virol. 7913239-13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, T. M., M. Altfeld, X. G. Yu, K. M. O'Sullivan, M. Lichterfeld, S. Le Gall, M. John, B. R. Mothe, P. K. Lee, E. T. Kalife, D. E. Cohen, K. A. Freedberg, D. A. Strick, M. N. Johnston, A. Sette, E. S. Rosenberg, S. A. Mallal, P. J. Goulder, C. Brander, and B. D. Walker. 2004. Selection, transmission, and reversion of an antigen-processing cytotoxic T-lymphocyte escape mutation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 787069-7078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen, M. H., I. Sondergaard, J. Zeuthen, T. Elliott, and J. S. Haurum. 1999. An assay for peptide binding to HLA-Cw*0102. Tissue Antigens 54185-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrie, K. A., E. E. Perez, S. L. Lamers, W. G. Farmerie, B. M. Dunn, J. W. Sleasman, and M. M. Goodenow. 1996. Natural variation in HIV-1 protease, Gag p7 and p6, and protease cleavage sites within gag/pol polyproteins: amino acid substitutions in the absence of protease inhibitors in mothers and children infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology 219407-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bebenek, K., J. Abbotts, S. H. Wilson, and T. A. Kunkel. 1993. Error-prone polymerization by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Contribution of template-primer misalignment, miscoding, and termination probability to mutational hot spots. J. Biol. Chem. 26810324-10334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrow, P., H. Lewicki, X. Wei, M. S. Horwitz, N. Peffer, H. Meyers, J. A. Nelson, J. E. Gairin, B. H. Hahn, M. B. Oldstone, and G. M. Shaw. 1997. Antiviral pressure exerted by HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) during primary infection demonstrated by rapid selection of CTL escape virus. Nat. Med. 3205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao, J., J. McNevin, S. Holte, L. Fink, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 2003. Comprehensive analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific gamma interferon-secreting CD8+ T cells in primary HIV-1 infection. J. Virol. 776867-6878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao, J., J. McNevin, U. Malhotra, and M. J. McElrath. 2003. Evolution of CD8+ T cell immunity and viral escape following acute HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 1713837-3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen, G. B., R. T. Gandhi, D. M. Davis, O. Mandelboim, B. K. Chen, J. L. Strominger, and D. Baltimore. 1999. The selective downregulation of class I major histocompatibility complex proteins by HIV-1 protects HIV-infected cells from NK cells. Immunity 10661-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colgrove, R. C., A. Millet, G. R. Bauer, J. Pitt, and S. L. Welles. 2005. Gag-p6 Tsg101 binding site duplications in maternal-infant HIV infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 21191-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Draenert, R., S. Le Gall, K. J. Pfafferott, A. J. Leslie, P. Chetty, C. Brander, E. C. Holmes, S. C. Chang, M. E. Feeney, M. M. Addo, L. Ruiz, D. Ramduth, P. Jeena, M. Altfeld, S. Thomas, Y. Tang, C. L. Verrill, C. Dixon, J. G. Prado, P. Kiepiela, J. Martinez-Picado, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. Immune selection for altered antigen processing leads to cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape in chronic HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 199905-915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedrich, T. C., E. J. Dodds, L. J. Yant, L. Vojnov, R. Rudersdorf, C. Cullen, D. T. Evans, R. C. Desrosiers, B. R. Mothe, J. Sidney, A. Sette, K. Kunstman, S. Wolinsky, M. Piatak, J. Lifson, A. L. Hughes, N. Wilson, D. H. O'Connor, and D. I. Watkins. 2004. Reversion of CTL escape-variant immunodeficiency viruses in vivo. Nat. Med. 10275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goulder, P. J., R. E. Phillips, R. A. Colbert, S. McAdam, G. Ogg, M. A. Nowak, P. Giangrande, G. Luzzi, B. Morgan, A. Edwards, A. J. McMichael, and S. Rowland-Jones. 1997. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat. Med. 3212-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goulder, P. J., and D. I. Watkins. 2004. HIV and SIV CTL escape: implications for vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4630-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greene, W. C., and B. M. Peterlin. 2002. Charting HIV's remarkable voyage through the cell: basic science as a passport to future therapy. Nat. Med. 8673-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes, A. L., K. Westover, J. da Silva, D. H. O'Connor, and D. I. Watkins. 2001. Simultaneous positive and purifying selection on overlapping reading frames of the tat and vpr genes of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 757966-7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibe, S., N. Shibata, M. Utsumi, and T. Kaneda. 2003. Selection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with an insertion mutation in the p6gag and p6pol genes under highly active antiretroviral therapy. Microbiol. Immunol. 4771-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacks, T., M. D. Power, F. R. Masiarz, P. A. Luciw, P. J. Barr, and H. E. Varmus. 1988. Characterization of ribosomal frameshifting in HIV-1 gag-pol expression. Nature 331280-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlsson, A. C., S. G. Deeks, J. D. Barbour, B. D. Heiken, S. R. Younger, R. Hoh, M. Lane, M. Sallberg, G. M. Ortiz, J. F. Demarest, T. Liegler, R. M. Grant, J. N. Martin, and D. F. Nixon. 2003. Dual pressure from antiretroviral therapy and cell-mediated immune response on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease gene. J. Virol. 776743-6752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenig, S., A. J. Conley, Y. A. Brewah, G. M. Jones, S. Leath, L. J. Boots, V. Davey, G. Pantaleo, J. F. Demarest, and C. Carter. 1995. Transfer of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to an AIDS patient leads to selection for mutant HIV variants and subsequent disease progression. Nat. Med. 1330-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Gall, S., L. Erdtmann, S. Benichou, C. Berlioz-Torrent, L. Liu, R. Benarous, J. M. Heard, and O. Schwartz. 1998. Nef interacts with the mu subunit of clathrin adaptor complexes and reveals a cryptic sorting signal in MHC I molecules. Immunity 8483-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leslie, A. J., K. J. Pfafferott, P. Chetty, R. Draenert, M. M. Addo, M. Feeney, Y. Tang, E. C. Holmes, T. Allen, J. G. Prado, M. Altfeld, C. Brander, C. Dixon, D. Ramduth, P. Jeena, S. A. Thomas, A. St John, T. A. Roach, B. Kupfer, G. Luzzi, A. Edwards, G. Taylor, H. Lyall, G. Tudor-Williams, V. Novelli, J. Martinez-Picado, P. Kiepiela, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. HIV evolution: CTL escape mutation and reversion after transmission. Nat. Med. 10282-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, B., A. D. Gladden, M. Altfeld, J. M. Kaldor, D. A. Cooper, A. D. Kelleher, and T. M. Allen. 2007. Rapid reversion of sequence polymorphisms dominates early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 evolution. J. Virol. 81193-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, Y., J. McNevin, J. Cao, H. Zhao, I. Genowati, K. Wong, S. McLaughlin, M. D. McSweyn, K. Diem, C. E. Stevens, J. Maenza, H. He, D. C. Nickle, D. Shriner, S. E. Holte, A. C. Collier, L. Corey, M. J. McElrath, and J. I. Mullins. 2006. Selection on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteome following primary infection. J. Virol. 809519-9529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, Y., J. McNevin, H. Zhao, D. M. Tebit, M. McSweyn, A. K. Ghosh, D. Shriner, E. J. Arts, M. J. McElrath, and J. I. Mullins. 2007. Evolution of HIV-1 CTL epitopes: fitness-balanced escape. J. Virol. 8112179-12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahnke, L., and D. Clifford. 2006. Cytotoxic T cell recognition of an HIV-1 reverse transcriptase variant peptide incorporating the K103N drug resistance mutation. AIDS Res. Ther. 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marlowe, N., T. Flys, J. Hackett, Jr., M. Schumaker, J. B. Jackson, S. H. Eshleman, HIV Prevention Trials Network, and Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Groups. 2004. Analysis of insertions and deletions in the gag p6 region of diverse HIV type 1 strains. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 201119-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsh, S. G. E., P. Parham, and L. D. Barber. 2000. The HLA factsbook. A*02, p. 104-105. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 29.Marsh, S. G. E., P. Parham, and L. D. Barber. 2000. The HLA factsbook. Cw*01, p. 244-255. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 30.Martin-Serrano, J., T. Zang, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2001. HIV-1 and Ebola virus encode small peptide motifs that recruit Tsg101 to sites of particle assembly to facilitate egress. Nat. Med. 71313-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mason, R. D., M. I. Bowmer, C. M. Howley, M. Gallant, J. C. Myers, and M. D. Grant. 2004. Antiretroviral drug resistance mutations sustain or enhance CTL recognition of common HIV-1 Pol epitopes. J. Immunol. 1727212-7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musey, L., J. Hughes, T. Schacker, T. Shea, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 1997. Cytotoxic-T-cell responses, viral load, and disease progression in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 3371267-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connor, D. H., A. B. McDermott, K. C. Krebs, E. J. Dodds, J. E. Miller, E. J. Gonzalez, T. J. Jacoby, L. Yant, H. Piontkivska, R. Pantophlet, D. R. Burton, W. M. Rehrauer, N. Wilson, A. L. Hughes, and D. I. Watkins. 2004. A dominant role for CD8+ T-lymphocyte selection in simian immunodeficiency virus sequence variation. J. Virol. 7814012-14022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Partin, K., E. Wimmer, and C. Carter. 1991. Mutational analysis of a native substrate of the HIV-1 proteinase. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 306503-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters, S., M. Munoz, S. Yerly, V. Sanchez-Merino, C. Lopez-Galindez, L. Perrin, B. Larder, D. Cmarko, S. Fakan, P. Meylan, and A. Telenti. 2001. Resistance to nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitors mediated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p6 protein. J. Virol. 759644-9653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettit, S. C., S. Gulnik, L. Everitt, and A. H. Kaplan. 2003. The dimer interfaces of protease and extra-protease domains influence the activation of protease and the specificity of GagPol cleavage. J. Virol. 77366-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price, D. A., P. J. Goulder, P. Klenerman, A. K. Sewell, P. J. Easterbrook, M. Troop, C. R. Bangham, and R. E. Phillips. 1997. Positive selection of HIV-1 cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape variants during primary infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 941890-1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez, W. R., M. M. Addo, A. Rathod, C. A. Fitzpatrick, X. G. Yu, B. Perkins, E. S. Rosenberg, M. Altfeld, and B. D. Walker. 2004. CD8+ T lymphocyte responses target functionally important regions of protease and integrase in HIV-1 infected subjects. J. Transl. Med. 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samri, A., G. Haas, J. Duntze, J. M. Bouley, V. Calvez, C. Katlama, and B. Autran. 2000. Immunogenicity of mutations induced by nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors for human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T cells. J. Virol. 749306-9312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schacker, T., A. C. Collier, J. Hughes, T. Shea, and L. Corey. 1996. Clinical and epidemiologic features of primary HIV infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 125257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmitt, M., E. Harrer, A. Goldwich, M. Bauerle, I. Graedner, J. R. Kalden, and T. Harrer. 2000. Specific recognition of lamivudine-resistant HIV-1 by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. AIDS 14653-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shafer, R. W., S. Y. Rhee, D. Pillay, V. Miller, P. Sandstrom, J. M. Schapiro, D. R. Kuritzkes, and D. Bennett. 2007. HIV-1 protease and reverse transcriptase mutations for drug resistance surveillance. AIDS 21215-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith, M. Z., C. S. Fernandez, A. Chung, C. J. Dale, R. De Rose, J. Lin, A. G. Brooks, K. C. Krebs, D. I. Watkins, D. H. O'Connor, M. P. Davenport, and S. J. Kent. 2005. The pigtail macaque MHC class I allele Mane-A*10 presents an immunodominant SIV Gag epitope: identification, tetramer development and implications of immune escape and reversion. J. Med. Primatol. 34282-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.VerPlank, L., F. Bouamr, T. J. LaGrassa, B. Agresta, A. Kikonyogo, J. Leis, and C. A. Carter. 2001. Tsg101, a homologue of ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) enzymes, binds the L domain in HIV type 1 Pr55Gag. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 987724-7729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiegers, K., G. Rutter, H. Kottler, U. Tessmer, H. Hohenberg, and H. G. Krausslich. 1998. Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual Gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J. Virol. 722846-2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yokomaku, Y., H. Miura, H. Tomiyama, A. Kawana-Tachikawa, M. Takiguchi, A. Kojima, Y. Nagai, A. Iwamoto, Z. Matsuda, and K. Ariyoshi. 2004. Impaired processing and presentation of cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes are major escape mechanisms from CTL immune pressure in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 781324-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu, X. G., M. M. Addo, E. S. Rosenberg, W. R. Rodriguez, P. K. Lee, C. A. Fitzpatrick, M. N. Johnston, D. Strick, P. J. Goulder, B. D. Walker, and M. Altfeld. 2002. Consistent patterns in the development and immunodominance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific CD8+ T-cell responses following acute HIV-1 infection. J. Virol. 768690-8701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zybarth, G., and C. Carter. 1995. Domains upstream of the protease (PR) in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag-Pol influence PR autoprocessing. J. Virol. 693878-3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]