Abstract

Molecular differences in the envelope glycoproteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) determine virus infectivity and cellular tropism. To examine how these properties contribute to productive infection in vivo, rhesus macaques were inoculated with strains of single-cycle SIV (scSIV) engineered to express three different envelope glycoproteins with full-length (TMopen) or truncated (TMstop) cytoplasmic tails. The 239 envelope uses CCR5 for infection of memory CD4+ T cells, the 316 envelope also uses CCR5 but has enhanced infectivity for primary macrophages, and the 155T3 envelope uses CXCR4 for infection of both naive and memory CD4+ T cells. Separate groups of six rhesus macaques were inoculated intravenously with mixtures of TMopen and TMstop scSIVmac239, scSIVmac316, and scSIVmac155T3. A multiplex real-time PCR assay specific for unique sequence tags engineered into each virus was then used to measure viral loads for each strain independently. Viral loads in plasma peaked on day 4 for each strain and were resolved below the threshold of detection within 4 to 10 weeks. Truncation of the envelope cytoplasmic tail significantly increased the peak of viremia for all three envelope variants and the titer of SIV-specific antibody responses. Although peak viremias were similar for both R5- and X4-tropic viruses, clearance of scSIVmac155T3 TMstop was significantly delayed relative to the other strains, possibly reflecting the infection of a CXCR4+ cell population that is less susceptible to the cytopathic effects of virus infection. These studies reveal differences in the peaks and durations of a single round of productive infection that reflect envelope-specific differences in infectivity, chemokine receptor specificity, and cellular tropism.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) are capable of infecting several distinct cell types in vivo, including CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (43). Virus entry into these target cells is mediated by the binding of the viral envelope glycoprotein to CD4 expressed on the cell surface followed by secondary interactions with chemokine coreceptors, either CCR5 or CXCR4, that lead to fusion of the viral and cellular membranes (1, 12, 18, 23, 29, 32). Amino acid differences in the viral envelope glycoprotein determine which coreceptor the virus uses for entry and ultimately which cell types are susceptible to infection (9, 19, 31, 37, 45). Viruses that use CCR5 (R5 tropic) preferentially infect memory CD4+ T cells and macrophages, whereas viruses that use CXCR4 (X4 tropic) infect both naive and memory CD4+ T-cell subsets (16, 19, 38). Differences in the frequencies, tissue distributions, activation states, and turnover rates of susceptible target cell populations likely influence their probability of becoming infected and contributing to virus replication in vivo. Thus, differences in the viral envelope glycoprotein that determine target cell specificity may have profound effects on virus replication. Understanding how target cell tropism contributes to the dynamics of productive infection in an infected host may help to explain certain aspects of viral pathogenesis such as the basis for the R5-to-X4 switch in chemokine receptor specificity observed in some HIV-1-infected individuals (10, 16, 44) and the formation and maintenance of infected cell reservoirs in patients receiving antiretroviral drug therapy (14, 24, 25, 50).

The degree of cellular activation is an important factor in determining the amount of virus released by an infected cell. HIV-1 and SIV replication in CD4+ T cells was previously thought to require cellular activation (13, 47-49). Indeed, mitogenic stimulation of primary CD4+ lymphocytes is necessary for efficient replication of HIV-1 or SIV in culture. However, it is now recognized that virus replication can also occur in quiescent CD4+ T cells, albeit at reduced efficiency (20, 55, 56). Cells phenotypically defined as naive or resting memory CD4+ T cells can support productive replication of HIV-1 and SIV at a level that is approximately 5- to 10-fold lower on a per-cell basis than that seen for activated CD4+ T cells (20, 56). Thus, differences in the viral envelope glycoprotein that affect target cell tropism also likely influence the levels of virus replication in vivo.

The susceptibility of distinct target cell populations to the cytopathic effects of virus infection may also affect the duration of virus production. Studies of plasma viral load decay following the initiation of antiretroviral therapy indicate that the majority of productively infected CD4+ T cells turn over with a half-life of approximately 0.7 days in HIV-1-infected individuals (33). However, certain cell types, such as macrophages, appear to be more resistant to the cytopathic effects of viral infection and may survive and produce virus much longer in vivo (7). Perhaps the best illustration of this is the maintenance of high plasma viral loads following nearly complete depletion of CD4+ lymphocytes in macaques infected with an X4-tropic simian-HIV (SHIV) chimera (28). Analysis of tissues revealed that more than 95% of the infected cells remaining in these animals were macrophages (28). Furthermore, plasma viral loads of nearly 106 RNA copy eq/ml were sustained in the presence of a reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitor to block new rounds of infection (28). The half-life of infected naive and resting memory CD4+ T cells may also be considerably longer than that of activated CD4+ T cells that support high levels of virus replication. Although productive infection likely accelerates the turnover of these CD4+ T-cell populations, estimates for the half-life of latently infected resting memory CD4+ T cells range from 6 to 44 months (40, 46).

To investigate how amino acid differences in the viral envelope glycoprotein that affect virus infectivity and cellular tropism affect a single round of productive infection in vivo, we inoculated rhesus macaques intravenously with a mixture of three different envelope variants of single-cycle SIV (scSIV). Viral loads for each strain were measured independently using a multiplex real-time PCR assay specific for unique sequence tags introduced into each envelope variant. This approach allowed us to compare infections for viruses with defined sequence changes in envelope in a system that is not complicated by ongoing virus replication and evolution. By administering the viruses as a mixture to the same animals, these comparisons were also internally controlled for animal-to-animal variation in susceptibility to infection. Our results reveal differences in the peaks and durations of productive infection that are consistent with differences in infectivity and target cell tropism of each scSIV strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of sequence-tagged strains of scSIV differing in envelope.

Envelope variants of scSIV were created with unique sequence tags to allow independent analysis of viral loads in animals after mixed infection. The restriction sites ApaI, EagI, and MluI were introduced into the RT-coding region of pol in the scSIV proviral construct p239-FS−ΔPRΔIN by PCR mutagenesis using the primers dRT-AEMf and dRT-AEMr (CCCCGGCCGACGCGTTAAGAGAAATCTGTGAAAAGATGGAAAAGG and CGTCGGCCGGGGCCCAAAATTTAGAGACATCCCCAGAGCTGTTAG). Three 71- to 74-bp sequence tags were selected from the Arabidopsis thaliana genome by use of PrimerExpress 1.0 optimal primer/probe design software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for low-copy-number detection and for minimal similarity to sequences in the SIV and rhesus macaque genomes. These included sequences from the glutamate-1-semialdehyde-2,1-aminomutase (gsa), chlorophyll a oxygenase (cao), and geranylgeranyl reductase (ggr) genes. These sequence tags were generated by PCR elongation with ApaI and MluI restriction sites at their 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, using the following primer pairs: for gsa, GTGGGCCCAAGCCCACCCACTTCGATTACCAACTCCGACCGCCAGAGACAGCG and GTACGCGTGTCGCCGACATCTTTGATCTGAAACTCGCTGTCTCTGGCGGTCGGAG; for cao, GTGGGCCCGACGGGAAACCAGGATGTGTACGGAATACATGTGCGCATAGAGC and GTACGCGTTCGT TCACTGTGCCAAGATCAAGAGGACATGCTCTATGCGCACATGTAT TCC; and for ggr, GTGGGCCCCATCCGTGTGGAGGCTCATCCGATTCCTGAACATCCGAGACCACG and CGTGGTCTCGGATGTTCAGGAATCGGATGAGCCTCCACACGGATGGGGCCCAC. The three tags were then cloned into the ApaI and MluI sites of p239FS−ΔPRΔIN-AEM to create p239FS−ΔPRΔIN-gsa, p239FS−ΔPRΔIN-cao, and p239FS−ΔPRΔIN-ggr. Envelope sequences in p239FS−ΔPRΔIN-cao and p239FS−ΔPRΔIN-gsa were exchanged with sequences from pSP72-316TMopen and pBR155T3 (provided by T. Kodama, University of Pittsburgh Medical School) to create p316FS−ΔPRΔIN-cao and p155T3FS−ΔPRΔIN-gsa. A glutamic acid residue was changed to a stop codon at position 767 (E767*) by a G-to-T substitution at nucleotide 8902 (41) to create additional constructs expressing envelope glycoproteins with truncated cytoplasmic tails (TMstop). The resulting set of six proviral constructs included p239FS−ΔPRΔIN-ggr, p316FS−ΔPRΔIN-cao, p155T3FS−ΔPRΔIN-gsa, p239-E767*FS−ΔPRΔIN-ggr, p316-E767*FS−ΔPRΔIN-cao, and p155T3-E767*FS−ΔPRΔIN-gsa for the production of TMopen and TMstop strains of scSIVmac239, scSIVmac316, and scSIVmac155T3.

Cell culture infectivity assays.

Infectivity assays were performed on unstimulated rhesus peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), CEMx174 cells, and GHOST cells expressing human CD4 and either CCR5 or CXCR4 or both (35) (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Germantown, MD). For PBMC and CEMx174 cells, 1 × 106 cells were infected with 100 ng SIV p27 eq of scSIV strains expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) from the nef locus in a 100-μl volume for 2 h. Cultures were then expanded to a volume of 2 ml in R10 medium (RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 2.5% HEPES buffer solution, penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine) for 2 h. Cultures were then expanded to a volume of 2 ml and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. GHOST cells expressing CCR5 or CXCR4 and harboring a Tat-inducible GFP reporter gene were plated at 0.5 × 106 cells per well in D10 medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM] supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml hygromycin, 500 μg/ml G418, penicillin, streptomycin, l-glutamine, and 1 μg/ml puromycin) in 24-well plates. Cells were infected the following day with 100 ng SIV p27 eq of virus in 500 μl D10 medium for 2 h. After 2 h, 1.5 ml D10 medium was added to each well and the cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Four days after infection of CEMx174 cells or PBMC and 2 days after infection of GHOST cells, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed for EGFP expression by flow cytometry. Data were collected using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickenson, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo 6.4 (TreeStar, San Carlos, CA).

Preparation of concentrated stocks of scSIV for animal experiments.

scSIV was produced by cotransfection of 293T cells with the Gag-Pol expression construct pGPfusion and each of the following single-cycle proviral constructs: p239FS−ΔPRΔIN-ggr, p316FS−ΔPRΔIN-cao, p155T3FS−ΔPRΔIN-gsa, p239-E767*FS−ΔPRΔIN-ggr, p316-E767*FS−ΔPRΔIN-cao, and p155T3-E767*FS−ΔPRΔIN-gsa. 293T cells were plated at 3 × 106 cells per dish in 100-mm tissue culture dishes the day before transfection. Each plate was transfected with 5 μg of each construct by use of Transfectin lipid reagent (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. The next day, cells were washed twice with 5 ml serum-free DMEM to remove residual FBS, and the medium was replaced with 3 ml fresh DMEM containing 10% rhesus serum (Equitech-Bio, Kerrville, TX). Viral supernatants were harvested 24 h later and concentrated approximately 20-fold by repeated low-speed centrifugation at 1,800 × g in YM-50 ultrafiltration units (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Concentrated stocks of scSIV were stored in multiple 0.5-ml aliquots at −80°C.

Animals and housing.

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were housed at the New England Primate Research Center in an animal biosafety level 3 containment facility in accordance with standards of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and the Harvard Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee. Research was conducted according to the principles described in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and was approved by the Harvard Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee (2).

Inoculation of macaques with scSIV.

Twelve adult rhesus macaques were inoculated intravenously with mixtures of three different envelope variants of scSIV carrying unique sequence tags for independent analysis of viral loads by real-time PCR. Six animals received 5 μg p27 eq each of scSIVmac239 TMopen, scSIVmac316 TMopen, and scSIVmac155T3 TMopen (15 μg p27 eq total), and six animals received 5 μg p27 eq each of scSIVmac239 TMstop, scSIVmac316 TMstop, and scSIVmac155T3 TMstop (15 μg p27 eq total). To prevent anaphylactic reactions to foreign serum antigens, scSIV stocks for the intravenous inoculation of animals were prepared in medium supplemented with rhesus macaque serum rather than FBS. Inoculations were performed under ketamine-HCl anesthesia (15 mg/kg of body weight intramuscularly) by injecting 2- to 6-ml volumes of concentrated virus through a 22-gauge catheter placed asceptically in the saphenous vein.

Analysis of plasma viral RNA loads.

Viral RNA loads in plasma for each of the three envelope variants of scSIV were measured using a quantitative multiplex real-time RT-PCR assay based on previously described methods (15). Virus was recovered from 0.5- to 1.5-ml volumes of plasma by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 1 h at 5°C. Virus pellets were then resuspended in 50 μl lysis solution containing 3 M guanidine (Gu)-HCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mg/ml proteinase K for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were treated with 200 μl of Gu-thiocyanate/carrier solution containing 5.7 M Gu-thiocyanate, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.6), 1 mM EDTA, and 600 μg/ml glycogen and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Nucleic acids were precipitated by the addition of 250 μl isopropanol and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. RNA pellets were then washed in 70% ethanol, recovered by centrifugation, dried, and dissolved in 30 μl nuclease-free water supplemented with 10 mM dithiothreitol and 1 U/ml RNase-OUT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Duplicate RT-PCRs were prepared for each sample. Ten microliters of RNA template was mixed with 20 μl RT cocktail to yield final reaction conditions of 1× PCR II buffer (Applied Biosystems), 0.01% gelatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.02% Tween 20 (Sigma), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 150 ng random hexamers (Promega, Madison, WI), 20 U RNase-OUT, and 20 U Superscript II RT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RT reactions were performed in a thermocycler at 25°C for 15 min, 42°C for 40 min, 90°C for 10 min, and 25°C for 30 min followed by a 5°C hold. Upon completion of the RT reaction, the tubes were opened and a 20-μl PCR mixture was added to reach the indicated final concentrations of the following reagents: 1× PCR II buffer, 0.03% gelatin, 0.012% Tween 20, 4.5 mM MgCl2, 200 nM each primer, 100 nM each probe, 50 nM passive reference dye [5′-(6-carboxyfluorescein-TTTTTTTTTT-(C3-blocked)-3′], and 1.25 U TaqGold polymerase (Applied Biosystems). The following primer/probe sets were used for the detection of Arabidopsis sequence tags cao, gsa, and ggr: ara-caoF (GACGGGAAACCAGGATGTGT), ara-caoR (TCGTTCACTGTGCCAAGATCA), ara-caoP (CAL Fluor Red 610-CGGAATACATGTGCGCATAGAGCATGTC-Black Hole Quencher [BHQ]-2), ara-gsa1F (CCCACCCACTTCGATTACCA), ara-gsa1R (CGCCGACATCTTTGATCTGA), ara-gsa1P (CAL Fluor Orange 560-TCCGACCGCCAGAGACAGCGAG-BHQ-1), ara-ggrF (CATCCGTGTGGAGGCTCAT), ara-ggrR (CAAGAGCCACACGTTTCGAG), and ara-ggrP (Quasar 670-TTCCTGAACATCCGAGACCACGTAGGC-BHQ-2) (Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA). Assembled 50-μl PCRs were run and data assimilated on an MX3000P real-time PCR instrument (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) under the following amplification conditions: 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 1 min. Viral RNA copy equivalents in each test sample were determined by comparison to half-log dilutions ranging from 101 to 106 copies per reaction of an in vitro-transcribed RNA standard that contained all three sequence tags.

Analysis of proviral DNA loads in PBMC.

PBMC cryopreserved on day 7 postinoculation for each animal were thawed (10 to 20 million cells per sample) and stained with monoclonal antibodies to CD3 (SP34-2, Cy7 allophycocyanin; Becton Dickinson [BD], San Jose, CA), CD8 (RPA-T8, QD705; BD), CD4 (L200, allophycocyanin; BD), CD28 (CD28.2, ECD; Coulter, Fullerton, CA), CD45RA (5H9, fluorescein isothiocyanate; BD), and CD95 (DX2, Cy5 phycoerythrin; BD). Unconjugated CD8 was purchased from BD and conjugated to QD705 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as previously described (8). CD4+ lymphocytes were sorted into naive (CD3+ CD4+ CD8− CD45RA+ CD28+ CD95−), central memory (CD3+ CD4+ CD8− CD45RA− CD28+ CD95+), and effector memory (CD3+ CD4+ CD8− CD28− CD95+) populations by use of a BD fluorescence-activated cell-sorting Aria flow cytometer. After sorting, cell pellets consisting of up to 2 million lymphocytes per sample and devoid of residual wash buffer were frozen at −80°C for analysis by quantitative PCR.

Total nucleic acids were prepared from frozen cell pellets by a modification to the methods described above. Frozen pellets were quickly disrupted in 100 μl of lysis solution by sonication using a high-intensity cup horn (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT). The precipitated nucleic acids were suspended in 60 μl 1× TurboDNAse buffer (Ambion, Austin, TX) and then heated to 100°C for 5 min followed by quenching on ice to eliminate the RNA and denature the DNA template. Proviral DNA copy equivalents for each strain of scSIV in each DNA sample were determined using the tag-specific primer and probe sets and the multiplex real-time PCR conditions described above. In a separate assay, under the same PCR conditions, the cellular equivalents of recovered DNA were determined by measuring copy equivalents of the CCR5 gene by use of the following primers and probe: RHR5F01 (CCAGAAGAGCTGCGACATCC), RHR5R01 (CTAATAGGCCAAGCAGCTGAGG), and RHR5P01 (Texas Red-TTCCCCTACAAGAAACTCTCCCCGGTAAGTA-BHQ2) (Biosearch Technologies). A reference clone of the rhesus CCR5 promoter region, provided by Sunil Ahuja (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX) (36), was used to generate a standard curve. Cellular equivalents were calculated based on diploid genome equivalents of the CCR5 gene.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for SIV-specific antibodies.

Nunc immunoplates (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) were coated overnight with either whole-virus lysate prepared from aldrithiol-2-treated inactivated SIV CP-MAC (AIDS Vaccine Program, NCI-Frederick, Frederick, MD) (3) diluted to 0.1 μg p27 eq/ml in calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or recombinant SIVmac251 glycoprotein gp130 (ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc, Woburn, MA) diluted to 3 μg/ml in bicarbonate buffer. Antigen was removed and plates were washed once with water. Plates were blocked with a 1:30 dilution of Kirkegaard and Perry bovine serum albumin diluent/blocking solution concentrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) in either PBS (whole virus) or bicarbonate buffer (gp130 protein) for 15 min and washed once with water. Duplicate wells for each sample were incubated with 200 μl of a 1/20 dilution of plasma in PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T-20) plus 5% inactivated goat serum plus 5% inactivated FBS for 1 h. Wells were washed three times with PBS-T-20, and 100 μl of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G(Fc) (KPL) diluted in PBS-T-20 was added to each well for 1 h. The plates were then washed three times with PBS-T-20, and 200 μl of phosphatase substrate solution (KPL) was added to each well. After 30 min, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 50 μl of 3 N sodium hydroxide to each well, and the absorbance was read at 410 nm.

Statistical analysis of plasma viral loads.

Given the relatively small sample size, nonparametric statistical methods were used in the analysis. The distribution of peak viremia and virus-specific antibody responses between the two groups were compared using the exact Wilcoxon rank sum test (30). The area under the curve (AUC) was estimated using the longitudinally collected viremia data (log transformed) for each individual. Then, the distributions of AUCs between the two groups were compared using the exact Wilcoxon rank sum test. All P values reflect two-sided tests of significance.

RESULTS

Sequence-tagged envelope variants of scSIV.

We previously described a two-plasmid system for producing strains of SIV that are limited to a single cycle of infection that was specifically designed to minimize the possibility of recovering replication-competent viruses by recombination or nucleotide reversion (21). One plasmid carries a full-length SIV genome with nucleotide substitutions in the gag-pol frameshift site to inactivate Pol translation followed by backup deletions in the protease- and integrase-coding regions of pol (Fig. 1A). A second plasmid expresses Gag-Pol in trans and also contains inactivating mutations in the gag-pol frameshift site (21). Cotransfection of both plasmids into 293T cells results in the release of Gag-Pol-complemented scSIV that is capable of one round of infection. However, the progeny virus released from scSIV-infected cells does not contain Pol and cannot complete subsequent rounds of replication. Since neither the scSIV genome nor the Gag-Pol expression construct contains a functional frameshift site, any products of recombination between these two plasmids remain defective for replication. Cells infected with scSIV therefore express all of the viral gene products except Pol and release virus particles that package the viral RNA genome, but these progeny virions are unable to complete subsequent rounds of infection (21).

FIG. 1.

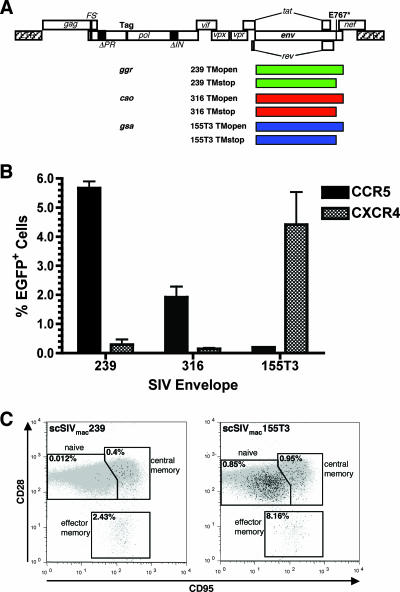

Envelope variants of scSIV. (A) Unique 71- to 74-bp sequence tags were introduced into the pol locus of scSIV strains expressing full-length (TMopen) and cytoplasmic tail-truncated (TMstop) forms of the 239, 316, and 155T3 envelope glycoproteins. These tags (ggr, cao, and gsa) were selected from the Arabidopsis thaliana genome by use of optimal primer-probe design software for low-copy-number detection by real-time PCR and the absence of cross-priming with sequences in the SIV and rhesus macaque genomes. Mutations that eliminate Pol expression from the scSIV genome, including three T→C substitutions in the ribosomal frameshift site (FS−) and backup deletions in the protease- and integrase-coding regions of pol (ΔPR and ΔIN, respectively) are indicated (21). (B) Chemokine receptor specificity of the 239, 316, and 155T3 envelope glycoproteins. GHOST cells expressing CCR5 or CXCR4 were infected with 50 ng p27 eq of SIVmac239, SIVmac316, and SIVmac155T3 and analyzed for EGFP expression after 2 days by flow cytometry. (C) The R5-tropic scSIVmac239 strain preferentially infects memory CD4+ T cells, while the X4-tropic scSIVmac155T3 strain infects naive and memory CD4+ T cells. Unstimulated rhesus PBMC (107 cells) were infected with 300 ng p27 eq of EGFP-expressing scSIV strains. Four days postinfection, PBMC were stained for CD4, CD28, and CD95 and analyzed by flow cytometry to differentiate naive (CD28+ CD95−), central memory (CD28+ CD95+), and effector memory (CD28− CD95+) CD4+ T-cell subsets. Infected EGFP+ cells (black) are superimposed on the total cell populations (gray) for each CD4+ T-cell subset.

Six different strains of scSIV were created that differ in infectivity, coreceptor utilization, and cellular tropism. Envelope sequences in the original scSIV genome based on SIVmac239 (21, 41) were exchanged with sequences from SIVmac316 that confer enhanced infectivity for macrophages (34) and sequences from SIVmac155T3 (38) that enable the virus to use CXCR4 rather than CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry. For each envelope variant, additional strains were constructed that expressed truncated forms of each envelope glycoprotein as a result of a glutamic acid -to-stop change at position 767 (E767*) in the cytoplasmic tail of gp41 (TMstop). Truncation of gp41 at this position was previously shown to increase virus infectivity as a result of increased envelope glycoprotein incorporation into virions (51, 52). The result was a set of six proviral constructs with defined sequence changes in envelope that included full-length (TMopen) and TMstop versions of scSIVmac239, scSIVmac316, and scSIVmac155T3 (Fig. 1A).

The envelope glycoproteins of SIVmac239 and SIVmac316 differ by eight amino acids, six in gp120 and two in gp41 (34). Both of these viruses use CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry (Fig. 1B) and have similar infectivities for phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-activated PBMC (21). Although both viruses are found in CD4+ T cells and macrophages in infected animals (6), SIVmac316 is 50- to 100-fold more infectious than SIVmac239 for primary alveolar macrophages in culture (21, 34). This difference appears to reflect the higher affinity of the 316 envelope for CD4, which enables the virus to infect macrophages expressing lower levels of CD4 on the cell surface (5).

SIVmac155T3 was originally derived from a macaque infected with SIVmac239 and differs by 22 amino acids in gp120 (T. Kodama, personal communication). These differences allow SIVmac155T3 to use CXCR4 rather than CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry (Fig. 1B). The absence of significant infectivity for CCR5-expressing cells suggests that these changes confer a complete shift from R5 to X4 tropism (Fig. 1B). The ability to use CXCR4 enables SIVmac155T3 to infect both naive and memory CD4+ T cells, in contrast to SIVmac239 infection, which is restricted to CCR5+ memory CD4+ T-cell subsets. This was confirmed by infecting unstimulated rhesus PBMC with strains of scSIVmac155T3 and scSIVmac239 engineered to express EGFP from the nef locus (Fig. 1C). Since naive CD4+ T cells are far more abundant in peripheral blood than are memory CD4+ T cells, the majority of cells infected by scSIVmac155T3 were naive CD4+ lymphocytes (Fig. 1C). These observations are consistent with a previous study by Picker et al. demonstrating that SIVmac155T3 infection of macaques leads to the depletion of naive CD4+ T cells, whereas SIVmac239 infection results in the preferential loss of memory CD4+ T cells (38).

To enable the quantitative detection of each virus in mixed infections, unique sequence tags were introduced into the viral genome of each scSIV envelope variant. Three 71- to 74-bp sequence tags were selected from the Arabidopsis thaliana genome by use of optimal primer/probe design software for low-copy-number detection and to minimize cross-priming with rhesus or SIV sequences. These included sequences from the gsa, cao, and ggr genes. Since Pol translation was silenced by upstream mutations in the gag-pol frameshift site (21), these tags were cloned into the scSIV genome at unique restriction sites engineered into the RT-coding region of pol (Fig. 1A). Quantitative amplification of these sequence tags was linear over more than 5 logs of dilution, with a threshold of >95% detection of five DNA copies (Fig. 2A) (15).

FIG. 2.

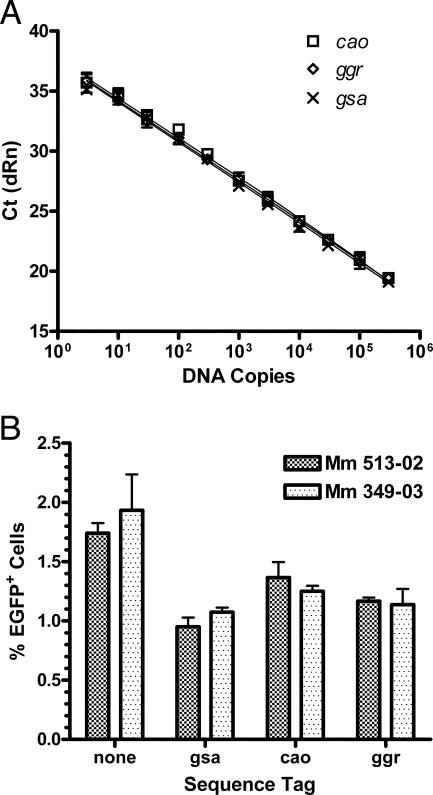

Sequence-tagged strains of scSIV do not differ in their infectivities for PHA-activated rhesus PBMC. (A) Real-time PCR amplification of cao, ggr, and gsa over a linear range of 3 to 3 × 105 input copies of proviral DNA. Reactions were performed in duplicate, and the threshold for >95% detection was five DNA copies per reaction. (B) PHA-activated PBMC from two different donor macaques were infected with 100 ng p27 eq of the parental scSIVmac239Δnef EGFP strain and derivates of this strain containing each sequence tag (gsa, cao, and ggr). On day 4 postinfection, the cells were fixed and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the percentages of infected cells expressing EGFP.

To determine if these foreign sequences affected virus infectivity, we tested the infectivities of scSIV recombinants carrying different tags, but expressing the same envelope glycoprotein, on PHA-activated PBMC from two different donor macaques. Compared to that of the untagged parental strain, the infectivities of the sequence-tagged strains of scSIV were reduced approximately 40% (Fig. 2B). Since the site selected for the introduction of the sequence tags did not disrupt any known cis-acting elements involved in the virus life cycle, the explanation for this relatively modest reduction in infectivity is presently unclear. It is possible that the introduction of these relatively G/C-rich sequences into an otherwise A/U-rich region of the viral genome may have diminished the stability, the nuclear export, or the efficiency of reverse transcription of the viral RNA. Nevertheless, no differences in infectivity were observed among the three sequence-tagged strains of scSIV (Fig. 2B).

Comparison of viral loads in plasma following inoculation of macaques with sequence-tagged envelope variants of scSIV.

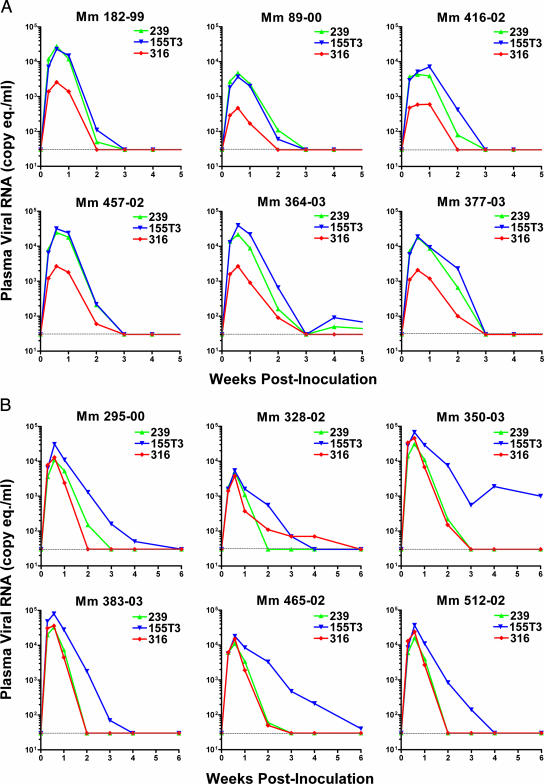

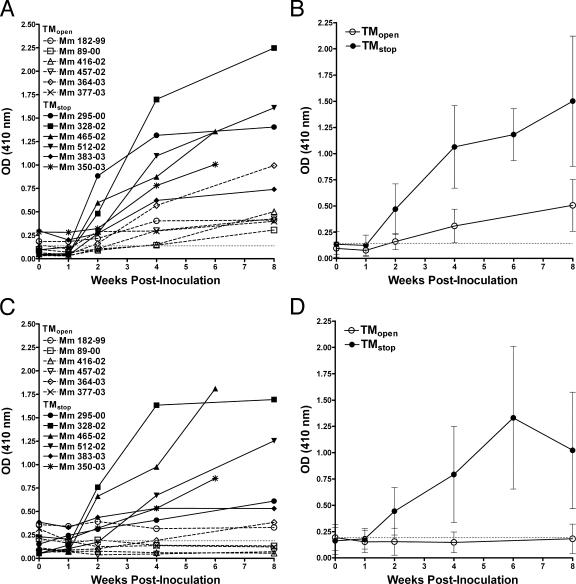

Rhesus macaques were inoculated intravenously with a mixture of sequence-tagged envelope variants of scSIV expressing the 239, 316, and 155T3 envelope glycoproteins to compare single rounds of productive infection in vivo for viruses differing in chemokine receptor specificity and cellular tropism. Six animals were inoculated with TMopen strains expressing full-length envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 3A), and six animals were inoculated with TMstop strains expressing envelope glycoproteins with truncated cytoplasmic tails (Fig. 3B). Each dose contained 5 μg p27 eq of each envelope variant (15 μg p27 eq total). Based on subsequent analysis of viral RNA content in the inoculum, this corresponded to doses of 3.5 × 1011, 3.4 × 1011, and 2.8 × 1011 RNA copy eq for TMopen scSIVmac239, scSIVmac316, and scSIVmac155T3 and to doses of 0.88 × 1011, 0.72 × 1011, and 0.83 × 1011 RNA copy eq for TMstop scSIVmac239, scSIVmac316, and scSIVmac155T3, respectively (Table 1). Thus, very similar amounts of each envelope variant were present in the TMopen and the TMstop scSIV inoculum mixtures based on assays for both SIV p27 and viral RNA. However, at equivalent doses of p27, the viral RNA content was 3.4- to 4.7-fold higher for the TMopen strains than for the TMstop strains. These differences appear to reflect, at least in part, variability in the SIV p27 antigen capture assays performed on separate occasions to measure the p27 content of each set of virus stocks. For in vivo comparisons between TMopen and TMstop strains of scSIV, we therefore adjusted plasma viral load measurements based on RNA copy equivalents rather than p27 equivalents in the inoculum (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Viral RNA loads in plasma following intravenous inoculation of macaques with a mixture of three different envelope variants of scSIV. Sequence-tagged strains of scSIV expressing full-length (A) or truncated (B) forms of the 239, 316, and 155T3 envelope glycoproteins were administered to each animal by intravenous injection. Each dose contained 5 μg p27 eq of each strain for a total of 15 μg p27 eq per dose. Viral RNA loads in plasma were measured for each strain independently by use of a quantitative multiplex real-time RT-PCR assay specific for the three sequence tags (ggr, cao, and gsa) engineered into each virus. The threshold of detection for this assay was 30 RNA copy eq/ml (dotted line). Mm, Macaca mulatta number.

TABLE 1.

scSIV inoculum

| Group | Strain of scSIVa | SIV p27 (μg)b | Viral RNA (copy eq)c | Infectivity

|

TMstop/TMopen inf. ratiof | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IU/ngd | IU/109 RNAe | |||||

| A | 239ggrTMopen | 5.0 | 3.47 × 1011 | 21.5 | 279 | |

| 316caoTMopen | 5.0 | 3.39 × 1011 | 5.4 | 71.7 | ||

| 155T3gsaTMopen | 5.0 | 2.82 × 1011 | 22.1 | 354 | ||

| B | 239ggrTMstop | 5.0 | 0.88 × 1011 | 40.8 | 2310 | 8.3 |

| 316caoTMstop | 5.0 | 0.72 × 1011 | 82.7 | 5760 | 80.3 | |

| 155T3gsaTMstop | 5.0 | 0.83 × 1011 | 56.7 | 3430 | 9.7 | |

Concentrated stocks of scSIV expressing the 239, 316, and 155T3 envelope glycoproteins with (TMstop) or without (TMopen) truncated cytoplasmic tails were prepared by cotransfection of 293T cells as previously described (21, 22). For independent analysis of viral loads by real-time PCR, 71- to 74-bp sequence tags derived from the Arabidopsis genome (ggr, cao, and gsa) were introduced into each strain.

The inoculum consisted of a mixture of three scSIV strains containing 5 μg p27 each of TMopen scSIVmac239, scSIVmac316, and scSIVmac155T3 (5 μg p27) for group A and TMstop scSIVmac239, scSIVmac316, and scSIVmac155T3 for Group B.

The viral RNA copy equivalents per dose for each strain of scSIV was determined by quantitative real-time PCR from DNase I-treated samples of the inoculum.

GHOST X4/R5 cells were infected with 50 ng p27 eq of each scSIV stock, and the frequency of GFP+ cells was determined by flow cytometry after 2 days. Infectious units per ng p27 (IU/ng) were calculated as the mean number of GFP+-infected cells from triplicate wells divided by the ng p27 input per well.

Infectious units per 1×109 viral RNA copy eq (IU/109 RNA).

Increase (n-fold) in infectivity (inf.) for TMstop versus TMopen strains of scSIV based on IU/109 RNA copy eq values.

FIG. 4.

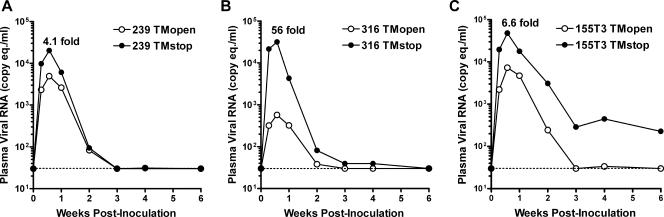

Truncation of the SIV envelope glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain increases the take of productive infection in animals. Mean viral RNA loads in plasma for animals inoculated with strains of scSIV expressing full-length (TMopen) versus truncated (TMstop) forms of the 239 (A), 316 (B), and 155T3 (C) envelope glycoproteins. Viral loads were normalized per 1011 RNA copy eq of each scSIV strain in the inoculum.

Infectivity titers for each stock were also determined on GHOST X4/R5 cells (35) (Table 1). Although the infectivity titers measured on this human osteosarcoma cell line almost certainly do not reflect the true infectivity of scSIV for primary rhesus target cells in vivo, they provide a measure of the relative infectivity of each strain on a common indicator cell line. The infectivity titers for each of the six strains were generally in the same range, indicating that there were no gross differences in the qualities of the virus stocks. Furthermore, differences in the infectivities of TMopen and TMstop strains of scSIV were similar to those found by previous cell culture infectivity measurements for TMopen versus TMstop SIVmac239 and SIVmac316 (51). Yuste et al. reported 2.5-fold and 480-fold increases in the infectivities of TMstop (E767*) SIVmac239 and SIVmac316, respectively, for LTR-SEAP-CEMx174 cells (51). We observed 8.3-fold and 80.3-fold increases in the infectivities for TMstop versus TMopen scSIVmac239 and scSIVmac316 (Table 1). Thus, although the magnitude of the infectivity enhancement for scSIVmac316 was less in this assay, the E767* truncation still had a much greater effect on the infectivity of scSIVmac316.

Viral RNA loads in plasma for each envelope variant were monitored for 6 weeks after inoculation by use of a multiplex real-time PCR assay specific for the unique sequence tags carried by each virus. Plasma viral loads peaked on day 4 postinoculation for all three envelope variants for both TMopen and TMstop scSIV strains and, with the exception of scSIVmac155T3 TMstop in two animals, were resolved below the threshold of detection of 30 RNA copy eq/ml within 6 weeks (Fig. 3). For both TMopen and TMstop strains, peak viremia was highest for scSIVmac155T3 (Table 2). However, the difference in peak viremias between scSIVmac155T3 and scSIVmac239 was not statistically significant for animals inoculated with either the TMopen or the TMstop strains (Table 3). For the TMopen strains, peak viremia was significantly lower for scSIVmac316 than for scSIVmac239 (P = 0.002) or for scSIVmac155T3 (P = 0.002). However, truncation of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail resulted in a peak of viremia for scSIVmac316 similar to that for scSIVmac239 (Table 2). Indeed, viral loads for scSIVmac316 TMstop and scSIVmac239 TMstop were almost superimposable (Fig. 3B).

TABLE 2.

Peaks of plasma viremia for six different envelope variants of scSIV

| Group | Strain of scSIV | Mean peak viral RNA (copy eq/ml)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Actuala | Adjustedb | ||

| A | 239ggrTMopen | 1.70 × 104 | 4.93 × 103 |

| 316caoTMopen | 1.86 × 103 | 5.70 × 102 | |

| 155T3gsaTMopen | 2.05 × 104 | 7.28 × 103 | |

| Total | 3.94 × 104 | 1.28 × 104 | |

| B | 239ggrTMstop | 1.78 × 104 | 2.03 × 104 |

| 316caoTMstop | 2.30 × 104 | 3.19 × 104 | |

| 155T3gsaTMstop | 3.99 × 104 | 4.81 × 104 | |

| Total | 8.07 × 104 | 1.00 × 105 | |

Plasma viral RNA loads peaked on day 4 postinoculation for each strain of scSIV and were determined using a quantitative multiplex real-time PCR assay based on amplification of the Arabidopsis sequence tags ggr, cao, and gsa. The values shown represent the averages of peak viral RNA for six animals.

Mean peak viral loads were adjusted per 1011 RNA copy eq of each scSIV strain in the inoculum.

TABLE 3.

Statistical comparison of the peaks of plasma viremia for each strain of scSIVa

| scSIV strain |

P value forb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMopen

|

TMstop

|

|||||

| 239 | 316 | 155T3 | 239 | 316 | 155T3 | |

| 239 TMopen | 0.002 | 0.70 | 0.01 | |||

| 316 TMopen | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |||

| 155T3 TMopen | 0.70 | 0.002 | 0.03 | |||

| 239 TMstop | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.14 | |||

| 316 TMstop | 0.002 | 0.56 | 0.31 | |||

| 155T3 TMstop | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.31 | |||

The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the distributions of peak viremia for each strain of scSIV. Comparisons between TMopen and TMstop strains of scSIV were done after adjusting for RNA copy equivalents of each strain in the inoculum. All P values reflect two-sided tests of significance.

P values for statistically significant comparisons (P < 0.05) are indicated in bold.

Since free virus is rapidly cleared from plasma with a half-life of just a few minutes (27, 53, 54), measurements of virion-associated RNA in plasma represent the steady-state release of noninfectious virus particles over the life span of productively infected cells. We therefore performed an AUC analysis on plasma viral loads for the entire period of productive infection to compare the total amounts of virus produced by cells infected with each strain of scSIV. We did not observe a significant difference in total virus production for scSIVmac239 TMopen versus scSIVmac155T3 TMopen (P = 0.49). However, viremia was significantly lower for scSIVmac316 TMopen than for scSIVmac239 TMopen (P = 0.002) and scSIVmac155T3 TMopen (P = 0.002) due to the lower take of infection by scSIVmac316 TMopen (Table 4). AUC analysis also revealed a significant difference in total viremia for scSIVmac155T3 TMstop versus scSIVmac239 TMstop (P = 0.004) and scSIVmac316 TMstop (P = 0.004). Since the peak height for scSIVmac155T3 TMstop did not differ significantly from the peaks of infection with the other TMstop strains (Table 3), this difference appears to reflect a delayed clearance of cells productively infected with scSIVmac155T3 TMstop. Indeed, while scSIVmac239 TMstop and scSIVmac316 TMstop were resolved within 2 to 3 weeks, viral loads for scSIVmac155T3 TMstop were detectable as late as 6 weeks after inoculation (Fig. 3B). Importantly, these viral RNA load measurements do not appear to reflect spreading infection, since the restoration of the pol open reading frame during the emergence of a replication-competent virus would result in the elimination of the sequence tag used to detect the virus. Furthermore, a standard assay for viral RNA based on RT-PCR amplification of sequences in gag yielded nearly identical viral load measurements at each time point (data not shown). These results are therefore consistent with scSIVmac155T3 TMstop infection of a cell population that is more resistant to the cytopathic effects of virus infection and/or better able to avoid elimination by virus-specific immune responses than cells infected with the R5-tropic TMstop strains of scSIV.

TABLE 4.

AUC comparison of viremias for each strain of scSIVa

| scSIV strain |

P value forb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMopen

|

TMstop

|

|||||

| 239 | 316 | 155T3 | 239 | 316 | 155T3 | |

| 239 TMopen | 0.002 | 0.49 | 0.82 | |||

| 316 TMopen | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |||

| 155T3 TMopen | 0.49 | 0.002 | 0.004 | |||

| 239 TMstop | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.004 | |||

| 316 TMstop | 0.002 | 0.70 | 0.004 | |||

| 155T3 TMstop | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | |||

The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the amounts of virus production as determined by AUC analysis for each strain of scSIV. Comparisons between TMopen and TMstop strains of scSIV were done after adjusting for RNA copy equivalents of each strain in the inoculum. All P values reflect two-sided tests of significance.

P values for statistically significant comparisons (P < 0.05) are indicated in bold.

Analysis of proviral DNA loads in peripheral blood CD4+ T-cell subsets.

CD4+ T-cell subsets in peripheral blood were also tested for cell-associated proviral DNA. Cryopreserved PBMC from day 7 postinoculation were sorted into naive, central memory, and effector memory CD4+ T-cell subsets on the basis of CD28 and CD95 staining, and nucleic acids were extracted for analysis of cell-associated proviral DNA. The copy equivalents of proviral DNA for each envelope variant were determined and normalized to diploid genome equivalents of the CCR5 gene to determine the frequency of scSIV-infected cells. Since the analytical sensitivity of the PCR assay was quite good, nominally set at five DNA copies per reaction or 30 total DNA copies per sample, the practical sensitivity of the assay was limited by the number of cells recovered for each population after sorting. In other words, the lower the cell yield for a given population, the higher the frequency of infected cells needed to reach the threshold for quantitative detection by PCR. Because of variation in the number of viable PBMC available for sorting, the frequency of CD4+ T-cell subsets, and the efficiency of recovery, the input cell numbers for each population varied considerably among samples.

With the exception of those for two animals, proviral DNA loads were at or below the limit of quantitative detection by PCR (<30 DNA copies), preventing a quantitative analysis of the frequency of infected cells (Table 5). Based on the range of cell yields for naive and central memory CD4+ T-cell subsets after sorting (Table 5), the predicted limits of detection for these samples, in terms of the frequency of infected cells necessary to reach the threshold of detection by PCR, were 39 to 208 naive and 65 to 188 central memory CD4+ T cells per million. For the effector memory subset, the sensitivity of detection was not as good (>417 infected cells per million) due to the much lower cell yields for this population (<150 to 72,000 cells). This likely accounts for the inability to detect proviral DNA in all but a single sample of effector memory cells. Overall, since relatively few infected CD4+ T lymphocytes harboring proviral DNA were detected in circulation at a time point close to the peak of viral RNA in plasma, these results suggest that the majority of scSIV-infected cells probably reside in the tissues.

TABLE 5.

Proviral DNA for each scSIV strain in naive and memory CD4+ T-cell populationsa

| Group | Animal | Presence of proviral DNA for indicated scSIV strain in indicated T-cell population

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive

|

Central memory

|

Effector memory

|

||||||||

| 239 | 316 | 155T3 | 239 | 316 | 155T3 | 239 | 316 | 155T3 | ||

| A | Mm 182-99 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Mm 89-00 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Mm 364-03 | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Mm 457-02 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| Mm 377-03 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Mm 416-02 | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| B | Mm 465-02 | − | − | − | 442 | + | + | − | − | − |

| Mm 512-02 | − | − | + | 482 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| Mm 328-02 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | |

| Mm 295-00 | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | |

| Mm 383-03 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | |

| Mm 350-03 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

Ten to 20 million cryopreserved PBMC from day 7 postinoculation were stained with antibodies to CD4, CD28, and CD95 and sorted into naive (CD28+ CD95−), central memory (CD28+ CD95+), and effector memory (CD28− CD95+) T-cell populations. Genomic DNA was extracted from snap-frozen cell pellets for each population and tested for the presence of proviral DNA for each scSIV strain by use of a multiplex real-time PCR assay based on amplification of the Arabidopsis sequence tags ggr, cao, and gsa. PCRs were performed in duplicate and had a threshold of detection of 30 DNA copy eq. Values indicate proviral DNA copy eq per 106 cells. Samples that tested positive in duplicate reactions, but were below the threshold of detection, are indicated with plus signs. Samples that tested negative in one or both reactions are indicated by minus signs. Based on quantitative amplification of the CCR5 gene, the samples ranged from 144,000 to 760,000 for naive CD4+ T cells, 160,000 to 460,000 for central memory CD4+ T cells, and <150 to 72,000 for effector memory CD4+ T cells.

Nevertheless, a number of samples tested positive for the presence of proviral DNA in duplicate PCRs at levels below the threshold required for quantitative analysis, thereby providing a qualitative picture of the distribution of the three viruses among naive and memory CD4+ T-cell subsets in vivo. The majority of positive samples were from animals inoculated with TMstop strains of scSIV (Table 5), reflecting the greater infectivity of strains expressing envelope glycoproteins with truncated cytoplasmic tails. Consistent with the predicted cellular tropism of these viruses, the only strain detected in the naive CD4+ T-cell population was scSIVmac155T3, while proviral DNA for all three viruses was detected in the central memory CD4+ T cells (Table 5). Thus, the distribution of each envelope variant among CD4+ T-cell subsets from infected animals was similar to the pattern of infectivity for each scSIV strain observed for unstimulated rhesus PBMC in culture (Fig. 2B).

Comparison of peak and total viral loads in plasma for animals inoculated with TMopen versus TMstop strains of scSIV.

Truncation of the cytoplasmic tail of the SIV envelope glycoprotein was previously shown to increase virus infectivity in culture as a result of increased envelope glycoprotein incorporation into virus particles (51, 52). To determine if truncation of the SIV gp41 cytoplasmic tail also increased virus infectivity in animals, mean plasma viral loads were compared for TMopen versus TMstop strains of each scSIV envelope variant. Mean plasma viral RNA loads for the six animals at each time point postinoculation were normalized per 1011 RNA copy eq of each virus in the inoculum to compensate for differences in the amounts of each strain administered as a result of variability in the p27 values determined by antigen capture ELISA. Truncation of the cytoplasmic tail resulted in significant increases in peak viremia on day 4 for all three envelope variants of scSIV (Table 3). However, this increase was much greater for scSIVmac316 TMstop (56-fold) than for scSIVmac239 TMstop (4.1-fold) or for scSIVmac155T3 TMstop (6.6-fold) (Fig. 4). AUC analysis also revealed significant increases in total viremia for scSIVmac316 TMstop (P = 0.002) and scSIVmac155T3 TMstop (P = 0.004) but not for scSIVmac239 TMstop (P = 0.82) (Table 4). Thus, truncation of the cytoplasmic tail of envelope significantly increased the take of a single round of productive infection in animals for three different envelope variants of scSIV, and similar to previous observations in culture (Table 1) (51), this increase was much greater for scSIVmac316.

Virus-specific antibody responses in animals inoculated with TMopen versus TMstop strains of scSIV.

Antibody responses in plasma were measured by ELISA to determine if binding antibody titers to SIV differed for animals inoculated with TMopen and TMstop strains of scSIV. SIV-specific antibody responses were detectable by week 2 and continued to increase during the first 8 weeks after inoculation (Fig. 5A). Consistent with greater infectivity and particle release for the TMstop strains, antibody titers to whole virus were on average 3.4-fold higher in the TMstop group than in the TMopen group (P = 0.0022; Wilcoxon rank sum test) at week 4 postinoculation (Fig. 5B). To determine if the TMstop strains also elicited greater antibody titers to envelope, antibody responses were measured on ELISA plates coated with purified recombinant SIV gp130. Although responses varied considerably among individual animals (Fig. 5C), mean envelope-specific antibody responses at week 4 postinoculation were 5.4-fold higher in animals inoculated with the TMstop strains than in those inoculated with the TMopen strains (P = 0.0022; Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

SIV-specific antibody responses in plasma. Values are shown for individual animals (A and C) and for averages for TMopen versus TMstop groups (B and D) at each time point. Antibody responses were measured at a 1/20 dilution of plasma on ELISA plates coated with whole-virus lysate prepared from AT-2-inactivated SIV (A and B) or with recombinant SIVmac251 gp130 (C and D). Background activity based on control wells incubated in the absence of plasma was subtracted from all values. The dotted line indicates the mean level of nonspecific binding for preimmune plasma from two animals tested in quadruplicate, and the error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean. Mm, Macaca mulatta number OD (410 nm), optical density at 410 nm.

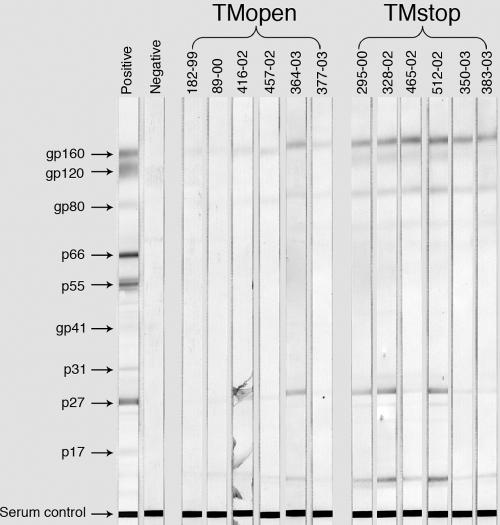

These differences were also reflected by the greater reactivity of plasma for SIV antigens by Western blotting. The envelope glycoprotein bands gp160, gp120, and gp80 and the p17 Gag band were more intense for plasma from the TMstop animals than for that from the TMopen animals (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the envelope glycoprotein bands were detectable with plasma from all six of the TMstop animals but from only three of the TMopen animals (Fig. 6). Thus, commensurate with increased infectivity, truncation of the gp41 cytoplasmic domain of scSIV increased antibody titers to whole virus and to the viral envelope glycoprotein.

FIG. 6.

Detection of SIV-specific antibody responses by Western blotting. SIV Western blot strips were probed with 1/100 dilutions of plasma collected at week 8 postinoculation and developed according to the manufacturer's instructions (ZeptoMetrix, Buffalo, NY). Arrows indicate the positions of bands corresponding to each of the major viral antigens. The serum control band represents an internal control to verify the reactivity of each strip. Control strips probed with positive and negative serum are indicated. Individual macaque numbers are given above the bands.

We also asked whether these increases in SIV-specific antibody titers were associated with a greater neutralization of infectious virus. Neutralizing antibody titers to a lab-adapted strain of SIVmac251 (SIVmac251LA) were measured for plasma samples collected at week 8 postinoculation. While three of the six animals in each group made low-titered neutralizing antibody responses (≤1:80) to SIVmac251LA, these titers did not differ significantly between animals inoculated with TMopen and TMstop strains of scSIV (data not shown). Therefore, despite significant increases in binding antibody titers to envelope, we did not observe a significant difference in neutralizing antibody titers for TMstop versus TMopen animals.

DISCUSSION

We compared the peaks and durations of productive infection after inoculation of macaques with a mixture of envelope variants of scSIV expressing full-length and truncated cytoplasmic tails. Since the half-life of SIV in plasma is short, as brief as 3 to 4 min (27, 53, 54), plasma viral load measurements reflect ongoing virus production from scSIV-infected cells in vivo. Viral loads in plasma peaked on day 4 for each strain, indicating that none of the envelope changes significantly altered the timing of peak viremia for the first round of infection. However, differences in the patterns of viremia were observed, reflecting envelope-specific differences in infectivity and target cell tropism. Truncation of the cytoplasmic tail of envelope at a position known to enhance SIV infectivity in cell culture significantly increased the peak of virus production in vivo for each envelope variant and the stimulation of virus-specific antibody responses. Conversely, amino acid differences in gp120 that determine CCR5 versus CXCR4 utilization, and thus the ability to infect distinct target cell populations, resulted in differences in the duration of the productive infection.

These observations extend previous cell culture studies on the effects of envelope cytoplasmic tail truncations on the infectivity of SIV. Yuste et al. demonstrated that the E767* substitution increased envelope incorporation into SIV by as much as 25- to 50-fold (11, 52, 57). However, this increase in infectivity was not proportional to the increase in envelope content in virions (51, 52). The E767* truncation resulted in a 25-fold increase in envelope incorporation for SIVmac239 but only a 2.5-fold increase in virus infectivity (51). In contrast, the same change in SIVmac316 resulted in a 14-fold increase in envelope incorporation and a 480-fold increase in virus infectivity (51). Although the differences in infectivity for the single-cycle versions of these viruses were lower under our assay conditions, we also observed an increase in the infectivity for scSIVmac316 TMstop greater than that for scSIVmac239 TMstop, i.e., 80.3-fold versus 8.3-fold, respectively. Since the E767* substitution was present in the original isolate of SIVmac316 (34), the greater effect of this change on the infectivity of SIVmac316 may reflect its origin as an important functional adaptation of the 316 envelope glycoprotein.

Consistent with the patterns of infectivity for TMstop versus TMopen viruses measured in culture, we found that truncation of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail increased virus infectivity in animals for each of the three envelope variants of scSIV tested. Significant increases in peak viremia were observed for TMstop versus TMopen scSIVmac239, scSIVmac316, and scSIVmac155T3. While these increases were relatively modest for scSIVmac239 and scSIVmac155T3, i.e., 4.1- and 6.6-fold, respectively, truncation of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail resulted in a 56-fold increase in peak viremia for scSIVmac316. Thus, the differences in peak viremia for the TMstop versus TMopen strains of scSIV in vivo were similar to differences in infectivity observed for each virus in prior cell culture assays.

Differences in the durations of plasma viremia were also observed for R5- versus X4-tropic strains of scSIV with truncated cytoplasmic tails. In animals inoculated with the TMstop strains, a more prolonged period of plasma viremia was observed for scSIVmac155T3 than for scSIVmac239 or scSIVmac316. Remarkably, viral RNA loads in plasma for scSIVmac155T3 TMstop were still detectable for two animals 6 weeks after inoculation. Since the assay for detection of viral RNA was dependent on RT-PCR amplification of a foreign sequence tag in pol, the emergence of a replication-competent virus would almost certainly result in the elimination of the sequence tag and the inability to detect the replicating variant by use of the tag-specific assay. However, nearly identical viral RNA load measurements were obtained using a standard RT-PCR assay based on the amplification of a conserved region of the SIV gag gene (data not shown), suggesting that no replication-competent virus was present and that the plasma viral loads for scSIVmac155T3 TMstop are not the result of copackaging of the viral genome by a replicating helper virus that had lost its sequence tag. Thus, viral loads for scSIVmac155T3 TMstop do not appear to represent spreading infection, and the simplest explanation for the prolonged period of viremia is ongoing virus production from a long-lived population of infected cells.

Differences in the susceptibilities of distinct CD4+ target cell populations to the cytopathic effects of virus infection could account for differences in their rates of turnover following infection with scSIV. Sustained virus production from infected macrophages was observed following nearly complete depletion of CD4+ lymphocytes in macaques infected with an X4-tropic SHIV (28). It is therefore possible that the infection of macrophages by scSIVmac155T3 TMstop may also have contributed to the slower resolution of viremia in some animals. Alternatively, prolonged viremia for scSIVmac155T3 TMstop animals may reflect the infection of quiescent naive or memory CD4+ lymphocytes. Resting CD4+ T cells have been implicated as a long-lived reservoir of virus infection in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy (14, 24, 25, 50). However, it is unclear whether latency is a prerequisite for their longevity. If so, virus production from this reservoir might require the periodic activation of a subset of latently infected cells. Yet another possibility is that the persistence of scSIVmac155T3 TMstop viremia in some animals may be the result of the infection of a population of progenitor cells that continue to divide and give rise to productively infected daughter cells. This hypothesis has been proposed to explain the persistence of a predominant population of identical HIV-1 clones in the plasmas of some patients on combination antiretroviral drug therapy that maintain viral RNA loads below 50 RNA copies/ml (4).

Target cell populations infected with R5- versus X4-tropic viruses in vivo may also differ in their susceptibilities to elimination by virus-specific immune responses. In animals coinfected with R5- and X4-tropic SHIVs, both viruses replicated during the first 2 weeks of infection, but by 3 to 6 weeks the R5-tropic virus predominated in plasma (26). While both strains remained resistant to neutralizing antibodies in serum, CD8 depletion resulted in the reemergence of the X4-tropic SHIV, suggesting that this virus was replicating in a CXCR4+ cell population that was more susceptible to virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (26). Although we observed the opposite trend, delayed clearance of X4-tropic rather than R5-tropic scSIV, differences in the susceptibilities of their respective target cell populations to elimination by virus-specific immune responses could also account for the differences observed in the durations of plasma viremia.

Virus-specific antibody and T-cell responses were monitored for each animal following scSIV inoculation. However, there were no clear associations between either of these immune responses and the clearance of scSIV viremia. Consistent with greater infectivity and virus production for the tail-truncated envelope variants, animals inoculated with the TMstop strains had significantly higher antibody titers to whole virus than did animals inoculated with the TMopen strains. Binding antibody responses to the envelope glycoprotein were also significantly higher in TMstop-inoculated animals, suggesting that increased cell surface expression of envelope and increased envelope density on virions as a result of the gp41 tail truncation may also have increased the availability of the protein for the induction of envelope-specific antibody responses. However, there was no detectable difference in virus-neutralizing antibody titers between the TMstop and TMopen animals. Likewise, both groups had similar frequencies of virus-specific T cells, as measured by gamma interferon enzyme-linked immunospot assays (data not shown). Thus, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the differential susceptibilities of these viruses or their infected target cell populations to immune responses may have contributed to strain-specific differences in the resolution of scSIV viremia in certain animals, we found no direct evidence to suggest that virus-specific immune responses contributed to the observed patterns of viremia.

Productive infection by scSIVmac155T3 was equivalent to or greater than that by scSIVmac239 or scSIVmac316 for each of the 12 animals in this study, suggesting that X4 tropism is not necessarily associated with limited virus amplification during the first stage of infection. Since naive CD4+ T cells are relatively quiescent and do not support virus replication as efficiently as memory CD4+ T cells, viruses that depend on CXCR4 for entry and preferentially infect naive CD4+ lymphocytes might be at a competitive disadvantage relative to R5-tropic viruses that replicate only in memory CD4+ lymphocytes. Indeed, this has been proposed as a possible mechanism to explain the rapid emergence of R5-tropic viruses in individuals infected with X4-tropic isolates of HIV-1 (17, 39, 42). However, following intravenous inoculation of macaques with equivalent doses of X4- and R5-tropic strains of scSIV, peak and total viral loads for the X4-tropic virus were as high as or higher than viral loads for the R5-tropic viruses, suggesting that this is not necessarily the case. Thus, X4 tropism per se does not appear to be associated with an inherent disadvantage in the first round of virus replication. Since both naive and memory CD4+ T cells express CXCR4, this may reflect the ability of X4-tropic viruses to infect a substantial number of memory as well as naive CD4+ lymphocytes. Alternatively, reduced levels of virus production on a per-cell basis for naive CXCR4+ target cells may be offset by their much greater abundance in peripheral blood and secondary lymphoid tissues.

Analysis of cell-associated proviral DNA loads in peripheral blood 1 week after inoculation suggests that the majority of scSIV-infected cells reside in the tissues. For 10 of 12 animals, proviral DNA loads in sorted naive and memory CD4+ T-cell populations were at or below the threshold of detection on day 7 postinoculation when total viral RNA loads in plasma exceeded 104 RNA copy eq/ml. Based on the copy limit of detection for proviral DNA and the number of cells used for nucleic acid extraction in each sample, the limit of detection for this assay ranged from 39 to 208 infected cells per million naive CD4+ lymphocytes and from 65 to 188 infected cells per million central memory CD4+ lymphocytes. Thus, frequencies of infection of greater than 0.021% for naive and 0.019% for central memory CD4+ T-cell populations should have been detectable. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that a very small number of infected cells were responsible for sustained viral loads in plasma, a more likely explanation for the disparity between plasma viral RNA and cell-associated proviral DNA measurements is that the majority of cells productively infected with scSIV reside in tissue compartments rather than in circulation.

By inoculating animals with a mixture of single-cycle viruses carrying unique sequence tags for quantitative detection by real-time PCR, we compared single rounds of virus infection and particle release for strains of scSIV with defined amino acid differences in envelope in a system that is internally controlled for individual variation in susceptibility to infection. These studies revealed differences in the peaks and durations of productive infection that reflect envelope-specific differences in virus infectivity, coreceptor specificity, and cellular tropism. In addition, these studies extend previous cell culture observations to show that truncation of the gp41 cytoplasmic domain increases virus infectivity in vivo and the stimulation of virus-specific antibody responses. The unique experimental approach described here may also be useful for investigating the influence of other genetic changes to the SIV genome upon a single round of virus infection in animals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI52751 and AI63993 from the National Institutes of Health. David T. Evans is an Elizabeth Glaser Scientist supported by the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib, G., C. Combadiere, C. C. Broder, Y. Feng, P. E. Kennedy, P. M. Murphy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 2721955-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. The Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, Washington, DC.

- 3.Arthur, L. O., J. W. Bess, E. N. Chertova, J. L. Rossio, M. T. Esser, R. E. Benveniste, L. E. Henderson, and J. D. Lifson. 1998. Chemical inactivation of retroviral infectivity by targeting nucleocapsid protein zinc fingers: a candidate SIV vaccine. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14S311-S319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey, J. R., A. R. Sedaghat, T. Kieffer, T. Brennan, P. K. Lee, M. Wind-Rotolo, C. M. Haggerty, A. R. Kamireddi, Y. Liu, J. Lee, D. Persaud, J. E. Gallant, J. Cofrancesco, T. C. Quinn, C. O. Wilke, S. C. Ray, J. D. Siliciano, R. E. Nettles, and R. F. Siliciano. 2006. Residual human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viremia in some patients on antiretroviral therapy is dominated by a small number of invariant clones rarely found in circulating CD4+ T cells. J. Virol. 806441-6457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannert, N., D. Schenten, S. Craig, and J. Sodroski. 2000. The level of CD4 expression limits infection of primary rhesus monkey macrophages by a T-tropic simian immunodeficiency virus and macrophagetropic human immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 7410984-10993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borda, J. T., X. Alvarez, I. Kondova, P. Aye, M. A. Simon, R. C. Desrosiers, and A. A. Lackner. 2004. Cell tropism of simian immunodeficiency virus in culture is not predictive of in vivo tropism or pathogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 1652111-2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, A., H. Zhang, P. Lopez, C. A. Pardo, and S. Gartner. 2006. In vitro modeling of the HIV-macrophage reservoir. J. Leukoc. Biol. 801127-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chattopadhyay, P. K., J. Yu, and M. Roederer. 2007. Application of quantum dots to multicolor flow cytometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 374175-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng-Mayer, C., M. Quiroga, J. W. Tung, D. Dina, and J. A. Levy. 1990. Viral determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 T-cell or macrophage tropism, cytopathogenicity, and CD4 antigen modulation. J. Virol. 644390-4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng-Mayer, C., D. Seto, M. Tateno, and J. A. Levy. 1988. Biologic features of HIV-1 that correlate with virulence in the host. Science 24080-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chertova, E., J. W. Bess, B. J. Crise, R. C. Sowder II, T. M. Schaden, J. M. Hilburn, J. A. Hoxie, R. E. Benveniste, J. D. Lifson, L. E. Henderson, and L. O. Arthur. 2002. Envelope glycoprotein incorporation, not shedding of surface envelope glycoprotein (gp120/SU), is the primary determinant of SU content of purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1and simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 765315-5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choe, H., M. Farzan, Y. Sun, N. Sullivan, B. Rollins, P. D. Ponath, L. Wu, C. R. Mackay, R. LaRosa, W. Newman, N. Gerard, C. Gerard, and J. Sodroski. 1996. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell 851135-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou, C.-S., O. Ramilo, and E. S. Vitetta. 1997. Highly purified CD25- resting T cells cannot be infected de novo with HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 941361-1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chun, T.-W., L. Stuyver, S. B. Mizell, L. A. Ehler, J. A. M. Mican, M. Baseler, A. L. Lloyd, M. A. Nowak, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9413193-13197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cline, A. N., J. W. Bess, M. Piatak, and J. D. Lifson. 2005. Highly sensitive SIV plasma viral load assay: practical considerations, realistic performance expectations, and application to reverse engineering of vaccines for AIDS. J. Med. Primatol. 34303-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connor, R. I., K. E. Sheridan, D. Ceradini, S. Choe, and N. R. Landau. 1997. Changes in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Exp. Med. 185621-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornelissen, M., G. Mulder-Kampinga, J. Veenstra, F. Zorgdrager, C. Kuiken, S. Hartman, J. Dekker, L. VenDerHoek, C. Sol, R. Coutinho, and J. Goudsmit. 1995. Syncytium-inducing (SI) phenotype suppression at seroconversion after intramuscular inoculation of a non-syncytium-inducing/SI phenotypically mixed human immunodeficiency virus population. J. Virol. 691810-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng, H., R. Liu, W. Ellmeier, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, P. D. Marzio, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. M. Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doms, R. W., and S. C. Peiper. 1997. Unwelcomed guests with master keys: how HIV uses chemokine receptors for cellular entry. Virology 235179-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckstein, D. A., M. L. Penn, Y. D. Korin, D. D. Scripture-Adams, J. A. Zack, J. F. Kreisberg, M. Roederer, M. P. Sherman, P. S. Chin, and M. A. Goldsmith. 2001. HIV-1 actively replicates in naive CD4+ T cells residing within human lymphoid tissues. Immunity 15671-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans, D. T., J. E. Bricker, and R. C. Desrosiers. 2004. A novel approach for producing lentiviruses that are limited to a single cycle of infection. J. Virol. 7811715-11725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans, D. T., J. E. Bricker, H. B. Sanford, S. Lang, A. Carville, B. A. Richardson, M. Piatak, J. D. Lifson, K. G. Mansfield, and R. C. Desrosiers. 2005. Immunization of macaques with single-cycle simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) stimulates diverse virus-specific immune responses and reduces viral loads after challenge with SIVmac239. J. Virol. 797707-7720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng, Y., C. C. Broder, P. E. Kennedy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272872-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finzi, D., J. Blankson, J. D. Siliciano, J. B. Margolick, K. Chadwick, T. Pierson, K. Smith, J. Lisziewicz, F. Lori, C. Flexner, T. C. Quinn, R. E. Chaisson, E. Rosenberg, B. Walker, S. Gange, J. Gallant, and R. F. Siliciano. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat. Med. 5512-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finzi, D., M. Hermankova, T. Pierson, L. M. Carruth, C. Buck, R. E. Chaisson, T. C. Quinn, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, R. Brookmeyer, J. Gallant, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. D. Richman, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 2781295-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harouse, J. M., C. Buckner, A. Gettie, R. Fuller, R. Bohm, J. Blanchard, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 2003. CD8+ T cell-mediated CXC chemokine receptor 4-simian/human immunodeficiency virus suppression in dually infected rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10010977-10982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Igarashi, T., C. Brown, A. Azadegan, N. Haigwood, D. Dimitrov, M. A. Martin, and R. Shibata. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralizing antibodies accelerate clearance of cell-free virions from blood plasma. Nat. Med. 5211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igarashi, T., C. R. Brown, Y. Endo, A. Buckler-White, R. Plishka, N. Bischofberger, V. Hirsch, and M. A. Martin. 2001. Macrophage are the principal reservoir and sustain high virus loads in rhesus macaques after the depletion of CD4+ T cells by a highly pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus/HIV 1 chimera (SHIV). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98658-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klatzmann, D., E. Champagne, S. Chamaret, J. Gruest, D. Guetard, T. Hercend, J.-C. Gluckman, and L. Montagnier. 1984. T-lymphocyte T4 molecule behaves as the receptor for human retrovirus LAV. Nature 312767-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehmann, E. L. 1998. Nonparametrics: statistical methods based on ranks. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- 31.Liu, Z.-Q., C. Wood, J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1990. The viral envelope gene is involved in macrophage tropism of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strain isolated from brain tissue. J. Virol. 646148-6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maddon, P. J., A. G. Dalgleish, J. S. McDougal, P. R. Clapham, R. A. Weiss, and R. Axel. 1986. The T4 gene encodes the AIDS virus receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell 47333-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markowitz, M., M. Louie, A. Hurley, E. Sun, M. D. Mascio, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 2003. A novel antiviral intervention results in more accurate assessment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication dynamics and T-cell decay in vivo. J. Virol. 775037-5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mori, K., D. J. Ringler, T. Kodama, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1992. Complex determinants of macrophage tropism in env of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 662067-2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morner, A., A. Bjorndal, J. Albert, V. N. Kewalramani, D. R. Littman, R. Inoue, R. Thorstensson, E. M. Fenyo, and E. Bjorling. 1999. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) isolates, like HIV-1 isolates, frequently use CCR5 but show promiscuity in coreceptor usage. J. Virol. 732343-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mummidi, S., M. Bamshad, S. S. Ahuja, E. Gonzalez, P. M. Feuillet, K. Begum, M. C. Galvis, V. Kostecki, A. J. Valente, K. K. Murthy, L. Haro, M. J. Dolan, J. S. Allan, and S. K. Ahuja. 2000. Evolution of human and non-human primate CC chemokine receptor 5 gene and mRNA: potential roles for haplotype and mRNA diversity, differential haplotype-specific transcriptional activity, and altered transcription factor binding to polymorphic nucleotides in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus J. Biol. Chem. 27518946-18961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Brien, W. A., Y. Koyanagi, A. Namazie, J. Q. Zhao, A. Diagne, K. Idler, J. A. Zack, and I. S. Y. Chen. 1990. HIV-1 tropism for mononuclear phagocytes can be determined by regions of gp120 outside the CD4-binding domain. Nature 34869-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picker, L. J., S. I. Hagen, R. Lum, E. F. Reed-Inderbitzin, L. M. Daly, A. W. Sylwester, J. M. Walker, D. C. Siess, M. Piatak, C. Wang, D. B. Allison, V. C. Maino, J. D. Lifson, T. Kodama, and M. K. Axthelm. 2004. Insufficient production and tissue delivery of CD4+ memory T cells in rapidly progressive simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 2001299-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pratt, R. D., J. F. Shapiro, N. McKinney, S. Kwok, and S. A. Spector. 1995. Virologic characterization of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in a health care worker following needlestick injury. J. Infect. Dis. 172851-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramratnam, B., J. E. Mittler, L. Zhang, D. Boden, A. Hurley, F. Fang, C. A. Macken, A. S. Perelson, M. Markowitz, and D. D. Ho. 2000. The decay of the latent reservoir of replication-competent HIV-1 is inversely correlated with the extent of residual viral replication during prolonged anti-retroviral therapy. Nat. Med. 682-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regier, D. A., and R. C. Desrosiers. 1990. The complete nucleotide sequence of a pathogenic molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 61221-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roos, M. T., J. M. Lange, R. E. DeGoede, R. A. Coutinho, P. T. Schellekens, F. Miedema, and M. Tersmette. 1992. Viral phenotype and immune response in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 165427-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sattentau, Q. J., and R. A. Weiss. 1988. The CD4 antigen: physiological ligand and HIV receptor. Cell 52631-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuitemaker, H., M. Koot, N. A. Kootstra, M. W. Dercksen, R. E. Y. DeGoede, R. P. vanSteenwijk, J. M. A. Lange, J. K. M. E. Schattenkerk, F. Miedema, and M. Tersmette. 1992. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell-tropic virus populations. J. Virol. 661354-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shioda, T., J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1991. Macrophage and T cell-line tropisms of HIV-1 are determined by specific regions of the envelope gp120 gene. Nature 349167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]