Abstract

Under natural conditions and in some experimental models, rabies virus infection of the central nervous system causes relatively mild histopathological changes, without prominent evidence of neuronal death despite its lethality. In this study, the effects of rabies virus infection on the structure of neurons were investigated with experimentally infected transgenic mice expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in neuronal subpopulations. Six-week-old mice were inoculated in the hind-limb footpad with the CVS strain of fixed virus or were mock infected with vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline). Brain regions were subsequently examined by light, epifluorescent, and electron microscopy. In moribund CVS-infected mice, histopathological changes were minimal in paraffin-embedded tissue sections, although mild inflammatory changes were present. Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling and caspase-3 immunostaining showed only a few apoptotic cells in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Silver staining demonstrated the preservation of cytoskeletal integrity in the cerebral cortex. However, fluorescence microscopy revealed marked beading and fragmentation of the dendrites and axons of layer V pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex, cerebellar mossy fibers, and axons in brainstem tracts. At an earlier time point, when mice displayed hind-limb paralysis, beading was observed in a few axons in the cerebellar commissure. Toluidine blue-stained resin-embedded sections from moribund YFP-expressing animals revealed vacuoles within the perikarya and proximal dendrites of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. These vacuoles corresponded with swollen mitochondria under electron microscopy. Vacuolation was also observed ultrastructurally in axons and in presynaptic nerve endings. We conclude that the observed structural changes are sufficient to explain the severe clinical disease with a fatal outcome in this experimental model of rabies.

Rabies is an acute viral infection of the central nervous system for which there is no effective antiviral therapy in humans (14). Despite its lethality, only relatively mild histopathological lesions are typically found under natural conditions, leading to the concept that neuronal dysfunction, rather than structural neuronal injury or cell death, is responsible for the clinical features and fatal outcome (8, 13). However, mechanisms of neuronal dysfunction in rabies virus infection are still not understood. Studies have investigated ion channel dysfunction (12), abnormalities in neurotransmitters (2, 3, 5), and electroencephalographic changes (9, 10) in rabies virus infection, but no consistent abnormality has been identified. Both nitric oxide neurotoxicity and excitotoxicity have been evaluated with experimental animal models of rabies, but no important role has yet been established for these mechanisms (13, 27). Li and colleagues (19) have suggested that the degeneration of neuronal processes and disruption of synaptic structures may form the basis for neuronal dysfunction in rabies virus infection. They showed severe destruction and disorganization of neuronal processes in silver-stained hippocampal sections from mice infected intracerebrally with the pathogenic N2C strain of rabies virus. In the present study, we have examined morphological changes in neurons, with an emphasis on the structural integrity of neuronal processes, following peripheral inoculation of transgenic mice expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in a subpopulation of neurons (7), which facilitates the visualization of morphological details of dendrites, axons, and presynaptic nerve terminals, in order to assess whether alterations of neuronal processes play an important role in the pathogenesis of rabies. Expression of YFP is very strong in layer V neurons in the cerebral cortex and in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, which are prominently infected in experimental rabies, although expression does not occur in many other infected neurons, which is a limitation of this approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

The challenge virus standard (CVS-11) strain of fixed rabies virus, which was obtained from William H. Wunner (The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA), was used in these studies.

Animals and inoculations.

The original colony of transgenic mice (C57BL background) expressing YFP in neurons (H-line) was generated by Feng and colleagues (7). In this study, B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-YFP)16Jrs/J male mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were mated with C57BL female mice (Charles River Canada, St. Constant, Quebec). In subsequent matings, male offspring expressing YFP were mated with females not expressing YFP. Mice with the YFP phenotype, determined by viewing ear notches with an I3 fluorescence filter, express YFP predominantly in neurons in layer V of the neocortex, in pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus, in mossy fibers of the cerebellum, and in dorsal root ganglia (7). Positive neurons are a small percentage of each population and consequently are viewed on a dark background. There is no YFP expression in the Purkinje cells or in the molecular layer of the cerebellum. Six- to 7-week-old YFP mice were inoculated in the right hind-limb footpad with 3.1 × 107 PFU of CVS in 0.03 ml or mock infected with the same volume of vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) (CVS infected, n = 23; mock-infected, n = 21).

Preparation of tissue sections.

YFP mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with buffered 4% paraformaldehyde when they developed hind-limb paralysis (CVS infected, n = 5; mock infected, n = 5), which occurred on day 6 postinoculation (p.i.) or after they became moribund between days 9 and 12 p.i. (CVS infected, n = 15; mock infected, n = 13). Brains were removed and immersion fixed in the same fixative for 24 h at 4°C. Coronal tissue sections (6 μm) were prepared from seven moribund mice and six mock-infected mice after dehydration and embedding in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E stain) and cresyl violet for light microscopic examination. Coronal sections (50 μm) of the remaining tissues were cut on a Leica VT 1000S vibratome (Leica, Germany) and transferred to slides for morphological studies using epifluorescence microscopy on a Leica microscope with an I3 filter or stored in 16-well plates in phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C for fluorescent rabies virus antigen staining (see below).

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained for rabies virus antigen by use of a mouse anti-rabies virus nucleocapsid protein monoclonal antibody (5DF12), which was obtained from A. I. Wandeler (Centre of Expertise for Rabies, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Nepean, Ontario, Canada), as previously described (17).

For rabies virus antigen detection in floating vibratome sections, tissue sections were subsequently incubated with 0.3% H2O2, blocked with 10% normal goat serum, and treated with the mouse anti-rabies virus nucleocapsid protein monoclonal antibody (5DF12) diluted 1:200 for 48 h at 4°C and Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (heavy plus light chains) fluorescent antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 18 h at 4°C in the dark. Slides were examined using fluorescence microscopy with an N21 filter.

Immunohistochemical staining for activated caspase-3 on paraffin-embedded tissue sections was performed using a polyclonal rabbit antibody against caspase-3 (catalog no. 9661; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) as described previously (25).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining.

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated and then heated in a microwave for 1 min at high power and 9 min at medium power in citrate buffer (pH 3). Sections were successively treated with 15 μg/ml proteinase K (Sigma), 3% H2O2, 1× blocking solution (Boehringer Mannheim), TdT buffer (5× buffer is 1 M sodium cacodylate and 150 mM Tris, pH 6.6, with bovine serum albumin), TdT enzyme solution (20 μl 5× TdT buffer, 4 μl 25 mM CoCl2, 0.24 μl biotin-16-dUTP [Roche], 75.72 μl distilled H2O, and 0.04 μl TdT enzyme [Roche]), 300 mM sodium chloride and 30 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.2), avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex, and 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride with 0.01% H2O2. Slides were counterstained with methyl green.

Bielschowsky silver staining.

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated prior to incubation in 20% silver nitrate for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Concentrated ammonium hydroxide was added to the silver nitrate solution until the initial precipitate disappeared, and slides were incubated in this solution for 15 min in the dark. Developer (20 ml 37% unbuffered formalin, 100 μl concentrated nitric acid, and 0.5 mg citric acid in 100 ml distilled H2O) was added to the silver nitrate solution and used to stain the slides prior to fixation with 5% aqueous sodium thiosulfate.

Electron microscopy.

YFP mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with Karnofsky's fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer) when they became moribund (CVS infected, n = 3; mock infected, n = 3). Brains were removed and immersion fixed in the same fixative for several days at 4°C and then immersed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, cleared with propylene oxide, and infiltrated with Jembed resin (J.B. EM Services, Dorval, Quebec, Canada). Sections (1 μm thick) of the frontal cortex, area CA1 of the hippocampus, and cerebellum from each mouse were stained with toluidine blue and examined by light microscopy. Ultrathin sections of the frontal cortex of two CVS-infected and two mock-infected mice were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a Hitachi H7000 electron microscope (Hitachi, Schaumburg, IL) at 75 kV.

Statistical analyses.

t tests for the significance of the difference between the means of two samples were used to compare the percentages of cortical and hippocampal pyramidal neurons displaying morphological abnormalities under fluorescence microscopy or cytoplasmic vacuolation in toluidine blue-stained tissue sections between CVS- and mock-infected YFP mice. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Rabies virus antigen distribution.

Staining for rabies virus antigen in paraffin-embedded tissue sections of CVS-infected moribund YFP mice on days 9 to 12 p.i. revealed widespread infection involving the vast majority of neurons in the hippocampus and in the cerebral cortex, including the perikarya and dendrites of pyramidal neurons in layer V (Fig. 1C). Control tissues showed low background staining.

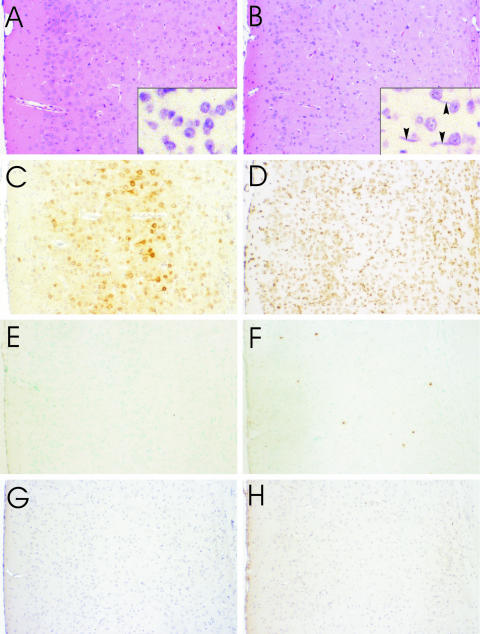

FIG. 1.

Cerebral cortex of mock-infected (A, E, and G) and CVS-infected moribund (B, C, D, F, and H) YFP mice with H&E staining (A and B), cresyl violet staining (A and B insets), immunoperoxidase staining for rabies virus antigen (C), TUNEL staining (D, E, and F), and immunostaining for activated caspase-3 (G and H). H&E staining shows a lack of degenerative neuronal changes in CVS infection (B) and the presence of inflammatory changes with activated microglia (arrowheads, B inset) in a diffuse distribution and widespread expression of rabies virus antigen in cortical neurons (C). TUNEL staining shows a strong signal with DNase pretreatment (D), a low background in mock infection (E), and signal in a few probable inflammatory cells in CVS infection (F). Caspase-3 staining shows low background staining in mock infection (G) and little staining in CVS infection (H). Magnifications: panels A to H, ×90; insets in panels A and B, ×520.

Fluorescent rabies virus antigen staining of floating vibratome sections revealed similar findings for moribund animals (days 9 to 12 p.i.) (data not shown). At 6 days p.i., staining was widespread in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex, while staining in the hippocampus was more limited, with various amounts of staining between animals ranging from sparse focal staining in a few hippocampal pyramidal neurons to intense staining in the majority of them. Rabies virus antigen could be localized in perikarya (Fig. 2F, inset) but not in the degenerating neuronal processes in the cerebral cortex with fluorescence microscopy, either because the sensitivity of the detection method was inadequate or because antigen expression was too low, possibly related to the degenerative process.

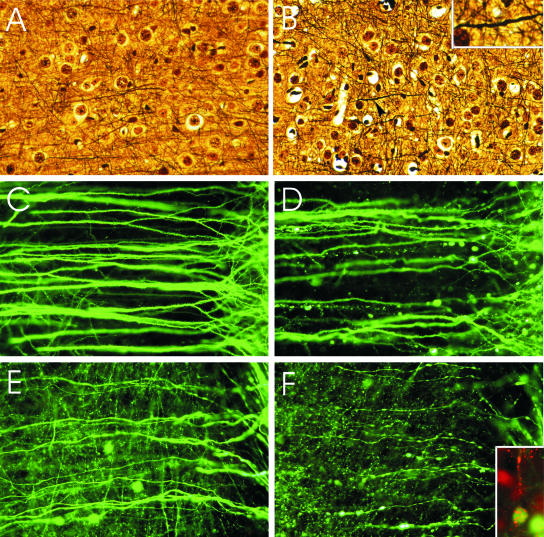

FIG. 2.

Silver staining of axons in the cerebral cortex of mock-infected (A) and moribund CVS-infected (B) YFP mice. Rare axons show minimal beading and wavy profiles (arrow indicates magnified area in inset). Fluorescence microscopy showing dendrites (C and D) and axons (E and F) of layer V pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex of mock-infected (C and E) and moribund CVS-infected (D, F, and F inset) YFP mice. In infected mice, beading is observed in a minority of dendrites (D), while more axons are involved (F). There are no abnormalities in the dendrites (C) or axons (E) of mock-infected mice. Axons in mock-infected mice are slightly varicose (E), which is characteristic of these fibers. (F inset) Fluorescence microscopy shows rabies virus antigen (red) in the perikaryon and dendrite of a YFP-expressing neuron. Magnifications: panels A and B, ×165; panel B inset, ×400; panels C to F, ×345; panel F inset, ×330.

Histopathological changes.

H&E (Fig. 1B)- and cresyl violet-stained paraffin-embedded tissue sections showed an absence of well-defined neuronal cytopathology, with mild inflammatory changes in CVS infection (Fig. 1B) versus what was seen for mock infection (Fig. 1A). Activated microglia were observed in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1B, inset) and in areas CA1 and CA3 of the hippocampus, and sparse mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates were present in both of these regions. Low-grade mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in the leptomeninges of the cerebral cortex. Inflammatory changes were more evident in the cerebellum, where activated microglia were more abundant, particularly in the molecular layer. The cerebellar leptomeninges displayed prominent infiltration by mononuclear inflammatory cells (data not shown).

TUNEL and caspase-3 staining.

TUNEL and caspase-3 staining was performed on tissue sections (Fig. 1D to H) and showed little evidence of apoptosis in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1F and H) and hippocampus of moribund YFP mice. TUNEL staining of the cerebral cortex showed only scattered positive cells, predominantly inflammatory, and no definite neuronal staining (Fig. 1F). There was rare TUNEL staining in the CA1 sector of the hippocampus. Background staining was low (Fig. 1E), and signals were strong on sections pretreated with DNase (Fig. 1D). Caspase-3 staining was observed only in occasional nonneuronal cells in the cerebral cortex of moribund mice (Fig. 1H), whereas mock-infected tissues showed only low background staining (Fig. 1G).

Silver staining.

Rare axons of CVS-infected moribund mice showed only mild degrees of beading with wavy profiles in the deep layers of the cerebral cortex (Fig. 2B), whereas mock-infected mice did not show these changes (Fig. 2A).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence microscopy revealed morphological abnormalities in neuronal processes of YFP mice that were very mild at 6 days p.i. but much more advanced in moribund YFP mice (Fig. 2C to F and 3). The observed changes ranged from interspersed swellings on intact processes (beading) (Fig. 2F and 3B) to severely distended segments of neuronal processes without apparent physical connections between the residual swollen pieces (fragmentation) (Fig. 2D and 3C). All evidence to date indicates that the beaded processes are still interconnected. However, dendrites that are beaded lose their spines (1) and are synaptically dysfunctional (18).

FIG. 3.

Morphology of the cerebellar mossy fibers of mock-infected YFP mice (A), of CVS-infected YFP mice at 6 days p.i. (B), and of moribund YFP mice (C). Mossy fiber axons in the cerebellar commissure of moribund mice show severe beading (C), whereas no abnormalities were observed in mock-infected mice (A) and relatively mild changes were seen at 6 days p.i. (B). Axons in the inferior cerebellar peduncles are normal in mock-infected mice (D) and show marked beading in CVS-infected moribund mice (E). Central tracts in the brainstem traveling rostrocaudally are normal in mock-infected mice (F) and display distended axonal profiles (arrowheads) with some degree of axonal loss in CVS-infected moribund mice (G). Magnifications: panel A, ×110; panel B, ×240; panel C, ×110; panels D and E, ×195; panels F and G, ×220.

At 6 days p.i., CVS-infected mice displayed rare beading in the distal dendrites and axons of layer V pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex and distal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. The mossy fibers of the cerebellum were most noticeably affected, with beading occurring in a few axons in the cerebellar commissure (Fig. 3B). Moribund mice displayed beading in 12.2% ± 2.7% of dendrites of layer V pyramidal neurons (Fig. 2D) compared to 0% of dendrites in mock-infected mice (P = 0.011) (Fig. 2C). Rare shrunken perikarya were also observed in the cerebral cortex. A greater proportion of the axons (40.5% ± 7.8%) of layer V pyramidal neurons showed beading in CVS-infected tissues by comparison with what was seen for their dendrites (Fig. 2F). There was beading of 2.4% ± 1.2% of axons in mock-infected tissues (P = 0.0016).

Mossy fibers in the cerebellum of moribund animals showed severe damage in the majority of axons within the cerebellar commissure (Fig. 3C) and less-severe beading in the white matter of the folia. Beading was also observed in the internal granular layer of the cerebellum, where extensions of the mossy fibers synapse with granule cells.

In moribund mice, tracts traveling rostrocaudally through the central brainstem, including the tectobulbar tract and the medial longitudinal fasciculus, displayed distended and possibly fragmented processes of variable severity (Fig. 3G). The fibers of the inferior cerebellar peduncles also consistently showed beading (Fig. 3E).

The CA1 sector of the hippocampus showed very few structural abnormalities in moribund mice. In most cases, infected tissues were morphologically indistinguishable from control tissues. Abnormal shrunken perikarya of CA1 pyramidal neurons were rare. Even more uncommon were changes in the distal dendrites, which took the form of mild dendritic beading.

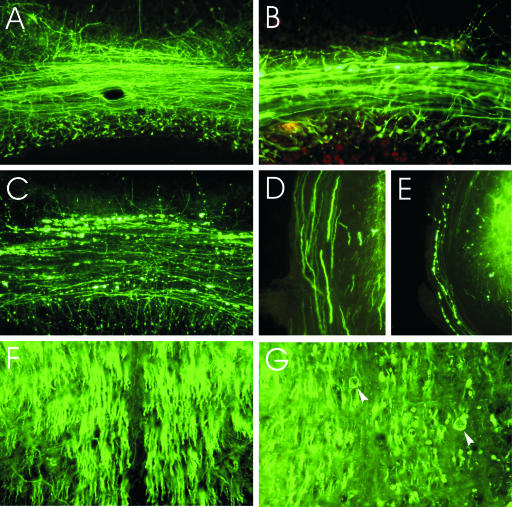

Toluidine blue-stained resin sections.

Morphological evaluation of toluidine blue-stained resin-embedded tissue sections was performed on mock- and CVS-infected mice (Fig. 4). Moribund CVS-infected YFP mice showed numerous round vacuoles within the cytoplasm of the perikarya and proximal dendrites of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 4B) and the CA1 sector of the hippocampus (Fig. 4D). In addition, larger vacuolations were also present within the neuropil of the cerebral cortex (Fig. 4B), and clusters of vacuoles of various sizes were present in a multifocal distribution. Overall, 60.8% ± 8.5% of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex of CVS-infected mice showed such vacuolation, whereas only 1.0% ± 0.2% showed these changes in mock-infected mice (P = 0.0021). Spherical vacuoles were observed in the cytoplasm and proximal dendrites of 21.7% ± 16.1% of CA1 pyramidal neurons in infected mice versus 0% in mock-infected animals (P = 0.4055) (Fig. 4C and D). The cerebellar white matter of CVS-infected mice had a diffusely vacuolated appearance, predominantly due to the enlargement and vacuolation of axonal profiles within myelinated fibers (Fig. 4F). Vacuoles were also present in the molecular layer of the cerebellar cortex.

FIG. 4.

Toluidine blue staining in the cerebral cortex (A and B), CA1 region of the hippocampus (C and D), and cerebellar white matter (E and F) of mock-infected (A, C, and E) and moribund CVS-infected (B, D, and F) YFP mice. Numerous round vacuoles are observed within the perikarya and proximal dendrites of many layer V pyramidal neurons in infected mice (B) but are rare in mock-infected mice (A). Vacuolation is also observed throughout the neuropil in infected mice (B). Round vacuoles are observed in smaller numbers of perikarya and proximal dendrites in CA1 pyramidal neurons of infected mice (D) but not in mock-infected mice (C). Vacuolation is observed within the cerebellar white matter of infected mice (F) and is not present in mock-infected mice (E). Magnifications: panels A to D, ×945; panel E, ×200; panel F, × 300.

Electron microscopy.

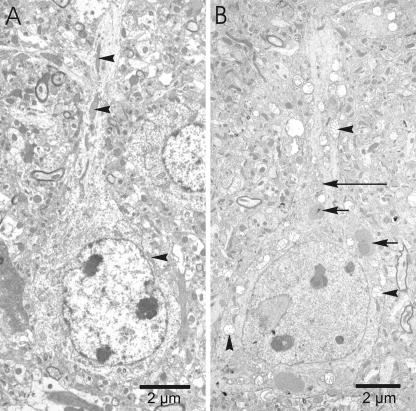

Electron microscopic examination of the cerebral cortex of moribund YFP mice showed swollen mitochondria within the perikarya, dendrites, and axons of many pyramidal neurons (Fig. 5 and 6). Swelling was also observed within the cisternae of the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 5B) in neurons with and without mitochondrial swelling. Pyramidal neurons in infected tissues also appeared to have somewhat less rough endoplasmic reticulum than those in control tissues. The swollen mitochondria likely correspond with the numerous round vacuoles observed within the perikarya and proximal dendrites of pyramidal neurons in toluidine blue-stained sections of the cerebral cortex.

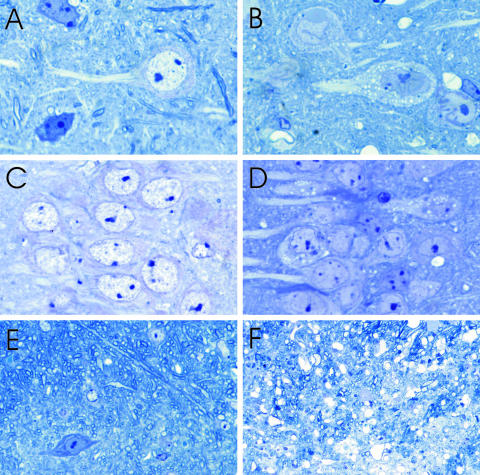

FIG. 5.

Electron micrographs of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex of a mock-infected (A) and a CVS-infected (B) YFP mouse. (A) The pyramidal neuron of a mock-infected mouse shows elongated mitochondria with compact cristae (arrowheads). (B) Swollen mitochondria (arrowheads) are present throughout the cytoplasm of the perikaryon and proximal dendrite of a CVS-infected pyramidal neuron, while the nuclear membrane and plasma membrane remain intact. Virus nucleocapsid material (short arrows) and swollen Golgi apparatus (long arrow) are also observed in the cytoplasm of the perikaryon.

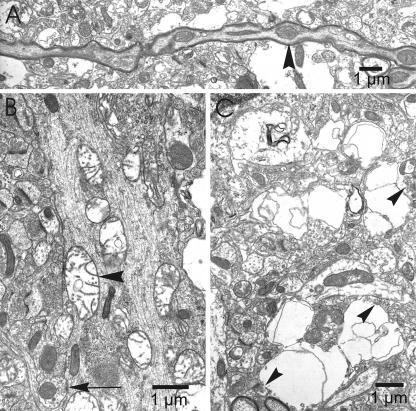

FIG. 6.

Electron micrographs of an axon (A), dendrite (B), and neuropil (C) in the cerebral cortex of a CVS-infected moribund YFP mouse. (A) Axon of a pyramidal neuron containing swollen mitochondria (arrowhead) that correspond with areas of beading. (B) Dendrites also contain swollen mitochondria (arrowhead), while the microtubules and an axodendritic synapse (arrow) are morphologically normal. (C) Vacuoles in the neuropil of infected tissues contain synaptic vesicles (arrowheads), indicating that they are neuronal in origin and represent presynaptic nerve endings.

Swollen mitochondria tended to colocalize with areas of increased diameter in neuronal processes, suggesting that the axonal (Fig. 6A) and dendritic beading observed by fluorescent microscopy may, at least in part, be the result of mitochondrial swelling in neuronal processes. Even with these morphological alterations, intact axodendritic (and likewise axosomatic) synapses were frequently present along segments of dendrites, including areas of beading. Also, intact microtubules were observed throughout neuronal processes.

The neuropil vacuolation observed in toluidine blue-stained tissue sections was found ultrastructurally to correspond predominantly with swollen neuronal processes, including markedly distended presynaptic nerve endings (Fig. 6C). Many of these neuropil vacuoles were found to contain swollen mitochondria and membranous-type debris. Such vacuoles frequently contained focal collections of synaptic vesicles immediately adjacent to synaptic densities, establishing their identity as presynaptic nerve endings. Some vacuoles were present in cellular elements that could not be definitively identified, and the possibility of swollen astrocytic processes, particularly when the vacuoles were located immediately adjacent to blood vessels, could not be excluded.

Despite the above-described ultrastructural changes and the presence of nucleocapsid material in the majority of pyramidal neurons, these neurons did not display signs of overt degeneration. In particular, there was no evidence of swelling of the cell bodies or loss of integrity of the plasma or nuclear membranes. The nucleoli were unremarkable, and there was no clear evidence of abnormal chromatin condensation.

DISCUSSION

Rabies is one of the most lethal of all infectious diseases. Natural rabies and animal models of rabies using peripheral inoculation are typically associated with relatively mild neuropathology and few degenerative neuronal changes. The characteristic pathological feature of rabies is inflammation of the brain and spinal cord (encephalomyelitis), which was observed in the present study. Overall, there was no well-defined neuronal cytopathology in the brains of mice by use of standard light microscopic evaluation of H&E- or cresyl violet-stained paraffin-embedded tissue sections. This was despite the advanced neurological disease and widespread infection demonstrated by viral antigen staining.

Apoptosis has been found to play an important role in the pathogenesis of rabies virus infection, but only under certain experimental conditions, including in models with suckling and adult mice inoculated intracerebrally (15, 16). In natural rabies, the role of apoptosis is less clear. Morphological observations indicate that neuronal apoptosis does not play a prominent role in human rabies (25). Following peripheral inoculation with CVS, which more closely reflects natural rabies infection than intracerebral inoculation, moribund YFP mice displayed only minimal TUNEL staining of inflammatory cells in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Similarly, staining for activated caspase-3 was rare in the cerebral cortex and was not observed in the CA1 sector of the hippocampus. Hence, there was little evidence of neuronal apoptotic cell death in this model.

The mild histopathological changes, without evidence of any significant degree of neuronal death, observed for moribund YFP mice by routine light microscopy support the idea that neuronal dysfunction, rather than neuronal death, is responsible for the clinical features and fatal outcome in rabies (8, 13). However, in the present study previously unrecognized changes in the morphology of neuronal processes and organelle structure were observed in moribund YFP mice by use of more-sensitive detection methods. Fluorescence microscopy revealed beading of the dendrites and axons of layer V pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex, cerebellar mossy fibers, and axons in the brainstem, whereas perikarya and neuronal processes in the hippocampus showed relatively few changes. We suspect that changes were likely also present in other neuronal populations that did not express YFP. These morphological findings appeared relatively late in the time course of infection, with beading found to involve only a few axons in the cerebellar commissure at day 6 p.i., indicating that these changes do not function to limit the spread of rabies virus through the neuroaxis.

Although the morphological changes observed in the neuronal processes of moribund YFP mice closely resemble the formation of large swellings or “beads” that are typical features of excitotoxicity (22), there are important differences in the localizations of these structural abnormalities that suggest that excitotoxicity is not likely the cause of beading in rabies virus-infected neurons. In particular, the hippocampus is among the brain regions most vulnerable to excitotoxic injury (23). This study demonstrated relatively few structural abnormalities in the hippocampus of CVS-infected YFP mice. The presence of axonal beading in rabies virus-infected tissues is another distinguishing feature that differs from excitotoxicity, which is characterized by selective dendritic injury (11, 24, 26).

Light microscopic examination of toluidine-stained thin sections of resin-embedded tissue from moribund YFP mice revealed vacuoles within the perikarya and proximal dendrites of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, as well as larger vacuoles within the neuropil of the cerebral cortex. Ultrastructurally, the neuropil vacuolation primarily represented swollen neuronal processes and presynaptic nerve endings, while the cytoplasmic vacuoles corresponded with swollen mitochondria. However, microtubule fragmentation, which is a typical feature of excitotoxic injury (6), was not observed ultrastructurally in this study, and silver staining also showed preservation of cytoskeletal architecture.

The morphological changes observed in the present study differ from those reported by Li and colleagues (19), who described the destruction and disorganization of apical dendrites in the hippocampus of mice infected intracerebrally with the pathogenic CVS-N2C strain of rabies virus (21). In contrast, the processes of hippocampal neurons in moribund YFP mice showed very few structural abnormalities despite extensive rabies virus infection. Li et al. (19) also observed an almost complete loss of intracellular organelles, including the rough endoplasmic reticulum and free ribosomes, while a few mitochondria were still visible. In the present study, although there was an impression of some reduction in the quantity of rough endoplasmic reticulum, there was otherwise no apparent decrease in the number of intracellular organelles, but mitochondria and Golgi apparati were swollen. For reasons that are not entirely clear, the intracerebral route of inoculation is associated with pathological changes more severe than those seen for the peripheral route. In addition, the N2C strain is a more pathogenic strain than the CVS-11 strain used in the present study, which could account for the differences in cytoskeletal integrity and organelle structure.

The structural changes observed in YFP mice challenge the hypothesis that neuronal dysfunction (without morphological changes) is responsible for the clinical features and fatal outcome in rabies virus infection. Typically, natural rabies and peripheral models of rabies virus infection are associated with relatively mild neuropathological changes and few degenerative neuronal changes. However, we observed changes not only in the morphology of neuronal processes but also in organelle structure. We believe that these morphological changes are sufficient to explain the severe clinical disease and fatal outcome of rabies virus infection. The focal constrictions between varicosities could cause electrical isolation of dendrites from neuronal perikarya. These findings indicate that structural neuronal injury prominently involved neuronal processes with no evidence of neuronal death in rabies, and they readily explain the severe clinical disease with a fatal outcome.

The mechanisms producing ischemic swelling of neurons with associated beading of dendrites and axons involve failure of the Na+/K+ ATPase pump (1). Swelling of dendrites and presynaptic terminals has been observed following the cortical superfusion of cats with ouabain, a Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor which causes an intracellular buildup of sodium (20). The expression of Na+/K+ ATPase by use of proteomic profiling has been shown to decrease in mice infected with the B2C strain of rabies virus, resulting in an increase in intracellular sodium (4). Iwata et al. (12) also found reduced functional expression of voltage-dependent sodium channels and of inward rectifier potassium channels in rabies virus-infected mouse neuroblastoma cells. Hence, rabies virus infection may produce important direct or indirect effects on sodium and potassium channels and on Na+/K+ ATPase, which may be responsible for the observed morphological changes. Further experimental studies are needed to examine morphological changes of neuronal processes and the pathogenic mechanisms involved in other experimental models of rabies and in natural rabies, including human rabies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research grants MOP-64376 (to A. C. Jackson) and MOP-69044 (to R. D. Andrew) and the Queen's University Violet E. Powell Research Fund (to A. C. Jackson). C. A. Scott was the recipient of a National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Student Scholarship (2006-2007).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrew, R. D., M. W. Labron, S. E. Boehnke, L. Carnduff, and S. A. Kirov. 2007. Physiological evidence that pyramidal neurons lack functional water channels. Cereb. Cortex 17787-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouzamondo, E., A. Ladogana, and H. Tsiang. 1993. Alteration of potassium-evoked 5-HT release from virus-infected rat cortical synaptosomes. Neuroreport 4555-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ceccaldi, P.-E., M.-P. Fillion, A. Ermine, H. Tsiang, and G. Fillion. 1993. Rabies virus selectively alters 5-HT1 receptor subtypes in rat brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 245129-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhingra, V., X. Li, Y. Liu, and Z. F. Fu. 2007. Proteomic profiling reveals that rabies virus infection results in differential expression of host proteins involved in ion homeostasis and synaptic physiology in the central nervous system. J. Neurovirol. 13107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumrongphol, H., A. Srikiatkhachorn, T. Hemachudha, N. Kotchabhakdi, and P. Govitrapong. 1996. Alteration of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in rabies viral-infected dog brains. J. Neurol. Sci. 1371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emery, D. G., and J. H. Lucas. 1995. Ultrastructural damage and neuritic beading in cold-stressed spinal neurons with comparisons to NMDA and A23187 toxicity. Brain Res. 692161-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng, G., R. H. Mellor, M. Bernstein, C. Keller-Peck, Q. T. Nguyen, M. Wallace, J. M. Nerbonne, J. W. Lichtman, and J. R. Sanes. 2000. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron 2841-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu, Z. F., and A. C. Jackson. 2005. Neuronal dysfunction and death in rabies virus infection. J. Neurovirol. 11101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gourmelon, P., D. Briet, D. Clarencon, L. Court, and H. Tsiang. 1991. Sleep alterations in experimental street rabies virus infection occur in the absence of major EEG abnormalities. Brain Res. 554159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gourmelon, P., D. Briet, L. Court, and H. Tsiang. 1986. Electrophysiological and sleep alterations in experimental mouse rabies. Brain Res. 398128-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasbani, M. J., K. L. Hyrc, B. T. Faddis, C. Romano, and M. P. Goldberg. 1998. Distinct roles for sodium, chloride, and calcium in excitotoxic dendritic injury and recovery. Exp. Neurol. 154241-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwata, M., S. Komori, T. Unno, N. Minamoto, and H. Ohashi. 1999. Modification of membrane currents in mouse neuroblastoma cells following infection with rabies virus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1261691-1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson, A. C. 2007. Pathogenesis, p. 341-381. In A. C. Jackson and W. H. Wunner (ed.), Rabies, 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 14.Jackson, A. C. 2007. Human disease, p. 309-340. In A. C. Jackson and W. H. Wunner (ed.), Rabies, 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 15.Jackson, A. C., and H. Park. 1998. Apoptotic cell death in experimental rabies in suckling mice. Acta Neuropathol. 95159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson, A. C., and J. P. Rossiter. 1997. Apoptosis plays an important role in experimental rabies virus infection. J. Virol. 715603-5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson, A. C., C. A. Scott, J. Owen, S. C. Weli, and J. P. Rossiter. 2007. Minocycline therapy aggravates rabies in an experimental mouse model. J. Virol. 816248-6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirov, S. A., L. J. Petrak, J. C. Fiala, and K. M. Harris. 2004. Dendritic spines disappear with chilling but proliferate excessively upon rewarming of mature hippocampus. Neuroscience 12769-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, X. Q., L. Sarmento, and Z. F. Fu. 2005. Degeneration of neuronal processes after infection with pathogenic, but not attenuated, rabies viruses. J. Virol. 7910063-10068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe, D. A. 1978. Morphological changes in the cat cerebral cortex produced by superfusion of ouabain. Brain Res. 148347-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morimoto, K., D. C. Hooper, S. Spitsin, H. Koprowski, and B. Dietzschold. 1999. Pathogenicity of different rabies virus variants inversely correlates with apoptosis and rabies virus glycoprotein expression in infected primary neuron cultures. J. Virol. 73510-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliva, A. A., Jr., T. T. Lam, and J. W. Swann. 2002. Distally directed dendrotoxicity induced by kainic acid in hippocampal interneurons of green fluorescent protein-expressing transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 228052-8062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olney, J. W., T. Fuller, and T. de Gubareff. 1979. Acute dendrotoxic changes in the hippocampus of kainate treated rats. Brain Res. 17691-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park, J. S., M. C. Bateman, and M. P. Goldberg. 1996. Rapid alterations in dendrite morphology during sublethal hypoxia or glutamate receptor activation. Neurobiol. Dis. 3215-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossiter, J. P., and A. C. Jackson. 2007. Pathology, p. 383-409. In A. C. Jackson and W. H. Wunner (ed.), Rabies, 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 26.Vanicky, I., M. Marsala, and T. L. Yaksh. 1998. Neurodegeneration induced by reversed microdialysis of NMDA; a quantitative model for excitotoxicity in vivo. Brain Res. 789347-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weli, S. C., C. A. Scott, C. A. Ward, and A. C. Jackson. 2006. Rabies virus infection of primary neuronal cultures and adult mice: failure to demonstrate evidence of excitotoxicity. J. Virol. 8010270-10273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]